Sometimes when you find out a story used to be called something different right up until the marketing team stepped in, the original name can offer extra insight. Kings of Summer was originally called “Toy’s House”. The main character is called Joe Toy, and I did spend a bit of time wondering if this is a symbolic name. The boys build themselves a house in the woods and set about pretending that they’re living off the grid. And it really is a pretence, because all the while they’re using a sum of stolen money to buy roast chickens from a nearby fast food restaurant.

After learning the original name I realised this is basically a Doll’s House Story, in which characters play out a scenario in a form of play that becomes quite serious.

GENRE BLEND OF THE KINGS OF SUMMER

comedy, drama >> coming-of-age, adventure story

I will call this ‘quirky comedy’.

TAGLINE OF THE KINGS OF SUMMER

Why live when you can rule?

Bear in mind that this is a tagline, not a theme. A theme is not posed as a question but rather as a declarative sentence.

SENTENCE BEHIND THE STORY OF THE KINGS OF SUMMER

Unlike the tagline and marketing copy the writers’ designing principle is never made public, so I am guessing here. I bet it goes something like:

A boy learns that he can’t hasten the onset of manhood by rejecting society and the people who are closest to him.

SETTING OF THE KINGS OF SUMMER

This is a heavily symbolic setting. First we have the whole fairytale-esque symbolism of the forest thing going on. We just know anything taking place in the middle of the woods ain’t going to be a walk in the park.

The soundtrack to the film also gives us a clue about interpreting this setting. The song “Land Trunt” (played over the Game Night scene) for instance has a spaghetti Western vibe to it — this explains both the choice of ethnicity of the Italian tagalong kid and also the way the boys feel about their mission. They are cowboys, pioneers, opening up their own Wild West. Other music on the soundtrack is gangsta, e.g. “Pickpocket“. These boys are finding out who they are. One moment they’re cowboys; the next they’re gangsters.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE KINGS OF SUMMER

There are 3 main types of adventure stories — two of them are very old. The first is the Odyssean structure, in which a character goes on a long journey, meets a bunch of opponents and returns home a changed person. (Or maybe they find a new home.) This kind of story is about 3000 years old.

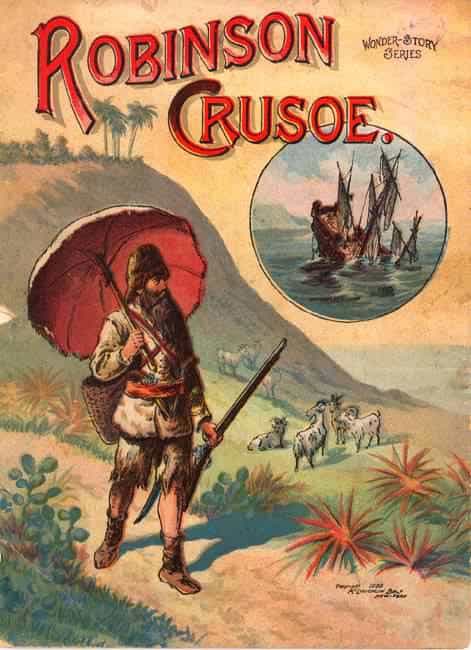

The second is the Robinsonnade, so named after Robinson Crusoe of course, in which a character doesn’t go anywhere but spends most of the story holed up somewhere — maybe it’s an island, maybe it’s a cabin in the woods — and the opponents are right there with him (it’s usually a him). This kind of story is as old as Robinson Crusoe.

Kings of Summer is — you guessed it — a Robinsonnade.

SHORTCOMING

Similar to Nadine, the main character of The Edge of Seventeen, Joe is a significantly flawed character.

Joe needs to become a man. This is to be pretty much expected when watching coming-of-age films starring boys. It’s clear how much pressure there is on boys to

- Not be women

- Not be gay

The problem is, while Joe has a few skills — plenty for his age — he certainly doesn’t have the wherewithal to leave civilisation behind. I am reminded of an interview I listened to with Jon Kraukauer, who wrote the 1996 biography of Christopher McCandless, Into The Wild. An enduring question most people have after either watching the film or reading the biography: Did Chris mean to die in the wild? Kraukauer thinks no. As a young man he himself did all sorts of reckless things as an intrepid rock climber and if you read his book about rock climbing (Into Thin Air) you’ll see that he came close to death himself. Kraukauer describes the mindset of certain young men who do these things — they really do believe they’re invincible. He argues that McCandless really did not mean to die in the wild. I believe the fictional character of Joe Toy (who is frolicking in the woods as if it’s his personal ‘toy’ playground) is a Chris McCandless/Jon Krakauer type of teenage boy: Full of swag and bravado and disdain for society.

The masculinity theme of the story is introduced near the beginning of the film when Joe has his t-shirt ripped off him by a gang of anonymous corridor bullies. Instead of expressing nervousness or admiration for Joe’s naked torso she nonchalantly offers him one of her t-shirts. It is clear that Kelly does not consider him a love interest. This is symbolised by the fact that he’s wearing a girly pastel yellow t-shirt with a rainbow on the front — and I don’t think it’s any coincidence that the rainbow is a gay symbol.

The character of Biaggio is a purely comic character who exists not only to make jokes and (at one point) give the audience a hilarious fright, but is also Joe’s reflection character: Biaggio is of small build, does not grow a beard in the wild and has no problem declaring that he is has no gender.

This is a kid who is completely at home with who he is. Baggio is the Fregley from Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid series, who is similarly immune to the huge pressures of adolescence. Greg Heffley is another boy character who is concerned with becoming a Man, which means finding his role in the masculine pecking order, aiming for as high as possible.

DESIRE

It’s not immediately clear what Joe wants. Well, it’s clear that he does not want to be living at home with his father, who annoys the hell out of him but this is not an active desire. It gradually dawns on the audience what Joe is planning with his friends. He is berated by his father for leaving ‘tools’ on the driveway. What’s he using the tools for? Turns out he’s building a house in the woods. Meanwhile, his best friend Patrick has a father who has a comically great habit of knocking on the wall of the den, saying there should be a stud in there. It’s only clear in hindsight that these boys have quite a bit of carpentry knowledge, and it has come from at least one of the fathers.

OPPONENT

- The parents

- The best friends

- Kelly — Joe’s love opponent

PLAN

We see the boys carrying out the plan rather than discussing it. This has been going on for a while before the story starts. They’ve been magpie-ing a variety of items — stealing from playgrounds, construction sites and people’s houses — in order to build their own sharehouse in the woods. They plan to move there as soon as it’s liveable. They will hunt for their own food and spend the rest of their days living apart from society, free from the pressures of home, school and work.

BIG STRUGGLE

There are two main struggles in this story:

- The interpersonal struggle, between the two best friends

- The struggle against nature, with the snake inside the house

The interpersonal big struggle comes about because of a girl. They both like this good-looking girl, who ends up choosing Patrick over Joe. Since Joe has a sense of entitlement about ‘getting the girl’, he can’t accept this. In his mind, he likes her more and he therefore deserves her. There is a big fight (an actual fisticuffs) between the boys and a seemingly irreparable rift. Joe declares that he needs to be left alone, and for a while, he is. He goes full wildman, obviously having run out of money for the precooked roast chickens (we learned exactly how much money was taken during the police station scene with the parents — it was under $300). He even ends up murdering a rabbit and skinning it, throwing away his “Living In The Wild” handbook, realising that there is no substitute for experience. This is a symbolic moment too: “There’s no preparation for adulthood like plain old teenager/life experience”.

The big struggle scene between the boys has been foreshadowed by a montage of scenes showing us how these characters are spending their time in the woods: A lot of time is spent playing childlike, competitive games.

Then of course there is the snake scene.

I watched this with my Australian-born husband who laughed and said, “A snake would never behave like that.” That’s true, but the thing is, sometimes writers of stories need ‘nature’ to make a strike. They did it in Jaws (even though sharks don’t hunt people). Larry McMurtry did it in Lonesome Dove with the impossible and infamous cottonmouth incident, killing one river-crosser and impressing upon the audience that nature can and will kill them off one by one. More recently we have Andy Weir’s The Martian, in which the main character is subjected to a horrific dust storm and must therefore leave his spaceship. In fact, horrific dust storms can’t happen on Mars because of its lack of atmosphere. If something hits you on Mars, it’s like being bashed with feathers. Weir has been criticised for this incident in an otherwise quite scientifically accurate story, and has said numerous times that he needed ‘nature to strike first’.

Snakes, sharks, storms… Writers across the generations have taken our natural fears and anthropomorphised them into beasts with intent to kill us. Fans of mimesis in storytelling need to put that aside in order to enjoy narrative. However, a comedy such as this one is over-the-top ridiculous in places, and just like the cheesy lines of Desperate Housewives, they can get away with more because of the knowingly satirical setting they’ve created. Kings of Summer never really strives for scientific accuracy and so we don’t expect it.

ANAGNORISIS

In the vast majority of stories the hero’s overall change moves from slavery to freedom. This doesn’t happen in this particular story — the hero’s plan for total and complete freedom is totally foiled — not least because he doesn’t really want it. (He wants a girlfriend, not to live like Chris McCandless.) At the end of the story Joe’s father advises him not to hurry to become a man. Joe has moved from slavery to freedom, back to slavery (for now). This is a comic tragedy.

NEW SITUATION

We know that Joe will eventually have some of the freedom he craves — he just has to get a few years older, then he’ll be off to college like his older sister. The subplot of the relationship between the older sister and her father has given us a clue that Joe will never be completely free from his family.

The final scene shows us the state of Joe’s friendship with his best friend. Meeting each other at the lights (significantly, the parents are in the drivers’ seats), they give each other the middle finger, but in comedic, playground fashion. We can guess that these guys are still friends, but their friendship has shifted for good. Now that his best friend has ‘got the girl’, they have left true boyhood irrevocably behind, and for a while they’re in that in between stage, sometimes childlike, sometimes behaving like adults.