Combining my study of film, novels, children’s literature and lyrical short stories, I’ve come up with a nine part story structure.

Other cultures historically carve up stories differently. For instance, East Asian audiences expect different things from story, and also differ in the amount of work they expect to put in.

Not all stories are ‘Complete Narratives’. Mood pieces, character sketches, experimental short stories (such as those by Lydia Davis and descriptions of setting/paintings have more in common with poetry, which become complete narratives only at Step Nine, when the audience completes the arc in an imaginative, collaborative process.

Reading is very creative—it’s not just a passive thing. I write a story; it goes out into the world; somebody reads it and, by reading it, completes it.

Margaret Mahy, New Zealand children’s author

I think structure is deep in us. We put it in stories we tell our friends. We want it. It’s how we create meaning.

Greta Gerwig

Story is very close to liturgy, which is why one’s children like to have the story repeated exactly as they heard it the night before. The script ought not to deviate from the prescribed form.

Hugh Hood

‘Once upon a time, in such and such a place, something happened.’ There are far more complex explanations, of course. […] Jack discovers a beanstalk; Bond learns Blofeld plans to take over the world. The ‘something’ is almost always a problem, sometimes a problem disguised as an opportunity. It’s usually something that throws your protagonist’s world out of kilter — an explosion of sorts in the normal steady pace of their lives: Alice falls down a rabbit hole; Spooks learn of a radical terrorist plot; Godot doesn’t turn up.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

STEP ONE: Paratext

Although this arrives first for the audience, it comes last for the storyteller.

An audience never comes cold to a story. Even a campfire story made up on the spot has the expectation of ‘tall tale’ based on the situation in which it is told. Let’s therefore consider all the things around a story part of the story itself, setting up expectations for the audience:

- Title

- Book cover or movie poster

- Blurb/Marketing copy/Logline

- Trailer

- End papers (especially in picture books)

- Decorated colophons (especially in picture books)

- Book design (font, formatting)

- Trade and audience reviews

- Merchandising

- The author’s social media persona

Creating effective paratext is a specialised skill and this essential part of storytelling has traditionally been left to marketing teams. Increasingly, however, stories we enjoy have been self- or indie- published, which means the storyteller is responsible for the paratext. This especially applies to self-publishers, but I’ve also heard literary agents say that a paragraph from the author’s query letter must be so well-crafted that it could be used as-is for its cover copy, and sometimes is, even for a traditionally published book with the benefit of a marketing team around it.

Paratext done well establishes audience expectation:

- Genre mix (adventure, action, romance…?)

- Mood, atmosphere (noir, ominous, upbeat?)

- Hints at the setting (dystopia? utopia? snail-under-the-leaf?)

- Age of the main characters (YA? Children? Adults? Older adults?)

- Intended audience (For kids? Teens? Adults? Mature adults?)

- Pacing (fast or slow)

- Is it a conventional story or a ‘lyrical’ one? (How hard will the audience have to work before deriving meaning?)

Over the years I’ve found writing critique groups tend to swap word documents with little by way of introduction to a new story apart from a (temporary) title. Anything else is sometimes seen as artificially guiding critique partners too much in their response. However, I’ve found that providing critique partners with a blurb-in-progress is the more natural introduction to a work, and more likely results in useful feedback. Swapping stories with no paratext is the ultimate test of a story, but since no ‘in-the-wild’ reader comes to a published story cold, asking for critique with no paratext whatsoever is the ultimate unnatural act.

The paratext is therefore a first and essential step of experiencing a story, for the audience.

STEP TWO: Shortcoming

Set up the main character. Who is the main character? This isn’t always obvious. Some stories are not about individuals but societies (see the short stories of Annie Proulx especially “Brokeback Mountain“, which is not a sweet love story as the movie paratext tried to tell us, but the tragedy of a homophobic community).

What’s going wrong in this microcosm of society, whether it’s a world, country, city, community or individual? (Most stories for kids are about individuals. Children are yet to step out from the home into the wider world.)

What do they not know at the beginning of the story? Sometimes these shortcomings are called ‘dramatic needs’. You may have heard the term ‘lack’. That’s Russian Formalist Vladimir Propp’s word. Another word commonly used is ‘flaw’.

How is the main character treating others badly? Not all main characters treat others badly. Children’s book characters, especially in picture books, are often The Every Child. In a Carnivalesque story, the child will often be deliberately generic so the reader can imagine themselves in the pages. The Every Child is traditionally a white boy. Dr Seuss gave us a boy AND a girl for his O.G. Carnivalesque picture book The Cat In The Hat, along with white, generic names, understanding that gender does function as a marker. Binary gender ensemble casts became the norma. Mary Poppins stars a boy and a girl who might as well be the same person. It’s impossible to tell them apart. Decades later we now have more stories about girls, but children’s literature is still trying to move past White Boy as The Every Child.

However, there are many children’s book examples of individuated children. Many picture books feature characters with significant and obvious flaws, often funny, and often flaws which depict them as self-absorbed rather than power hungry. (This describes two year olds.) In This Moose Belongs To Me by Oliver Jeffers, the boy’s shortcoming is that he wants to own another sentient creature, who has its own life to lead. A character such as Olivia the pig, who is very wearing on her mother, is more rounded and ‘human’ precisely because of her annoying habits.

In adult literature, the character with no real flaw is widely known as a Pollyanna. Certain adults have always wanted children’s characters to be models of behaviour, always punished for their misdemeanours. There is increasing recognition that punishment itself is problematic, and out of step with what we now know about child development. This shift away from punishment has coincided with an increase in morally flawed child main characters.

The adult equivalent of The Every Child is the character who arrives on stage with little to no backstory. Read short stories from the mid 19th century and earlier and you’ll often get a character’s family history in a nutshell. Modernist writers started the trend of leaving this out. Katherine Mansfield’s short stories are a great example. A character’s history is kept right off the page. To the reader, it seems as if they have just been born.

Even more significantly, it seems this way to the narrator, as well. The reader gets no backstory. All our impressions of this character come from these particular events in the limited time scale of this particular story, with no flash backs, no flash forwards, and with no commentary about how they got here, or how everything turned out 20 years later.

In lyrical short stories, while a certain amount of individuation is expected, characters presented to us in statu nascendi like is perhaps the preferred mode for the contemporary short story reader. The modernist way of writing short stories caught on.

What does the main character/society need to learn before life improves? Without setting this up, there is no room for a character arc.

In a carnivalesque children’s book there is often no character arc, as such. The book exists for the child to have fun. However, the carnivalesque story can be used for any purpose, for example to show that a scary situation is not so scary at all. A good example of the carnivalesque story with a character arc is There’s A Crocodile Under My Bed, in which a child is scared because her parents are going out. She creates her own crocodile companion to stand in for her fear, diminishing her fear by rendering it a fun playmate. She has learned to use her imagination to cope with her fear of abandonment.

Make Way For Ducklings is missing the Shortcoming and Plan steps of story, leading to the criticism of ‘weak characterisation’. However, it was adult reviewers making this judgment. The story is immensely popular among kids. A short, illustrated picture book compensates for a lot — pictures themselves tell a thousand words. These ducks step out on a mythic journey, narrowly avoiding death. The ducklings are The Every Child.

Goodnight Moon is another perplexing example of a highly successful children’s story which does not seem to conform to commonly accepted storytelling advice. However, look harder and a clear structure emerges. In this case there is zero individuation of main character. The bunny in bed is The Every Child, with no distinguishing features apart from looking like a rabbit.

Oftentimes, especially in comedy and adult thrillers (believe it or not), ‘what’s wrong’ with the character is that they are wearing a mask, metaphorical or actual. Where a character is not presenting their ‘true self’ to society, you can guarantee this will be remedied before the end. The mask always gets removed, often forcibly, by someone else. I haven’t found any successful exceptions to this ‘rule’, though there may be some out there, subverting the idea that in order to lead a fulfilling life we must present our true selves (whatever that means). Note that this ideology is very Western, not shared world over. I may just need to find my examples elsewhere, and I’m interested in looking further into that e.g. to Japan, where the concepts of omote (public face) and ura (secret face) are accepted and respected. In Japan, no one expects anyone else to rip off their social mask.

STEP THREE: Desire

We can talk about rhetorical desire and sexual desire (which comes to the fore in any story with a romance plot). Here I’m talking about rhetorical desire: wishes and wants in general, known or unknown by the person who has them.

What does the main character want? (In this particular story… not in general.) There will be a conscious desire as well as a deeper desire, and the two may be completely different. Your character probably knows what they want on the surface, but may not realise this stands for something much deeper e.g. the wish to solve a mystery may reveal a deeper desire to be taken seriously (Harriet the Spy). Psychoanalysts of the 20th century have said much about conscious vs repressed desires.

Not all Carnivalesque stories are picture books, but in a carnivalesque picture book the desire is always the same: To escape the watchful eye of parents and have fun. Likewise, the deep desires of adult characters in stories for adults don’t tend to be all that original because we all want (and need) similar things deep down. The surface desires will be individual to the story, however.

STEP FOUR: Opponent/Appearance of an Ally or Fun

The opponent is the character who stands in the way of your ‘main character’ getting what they want. The opponent does not have to look like a villain. In children’s stories ‘opponent’ is often also an ally, for example, well-meaning parents and teachers, or fantasy creatures who are fun but destruction. This is true of realistic stories for adults, too, of course.

When the main character is an animal, there’s sometimes a parallel subplot in which a human character is the one with the clear desire and plan. An excellent example of this is Kate diCamillo’s Mercy Watson Goes For A Ride, in which the old lady next door is the human proxy for the pig. This applies to animals who are not fully humanized (and would never be necessary in a book such as Olivia, in which the pig is for all intents and purposes a little girl.)

…give us a hero facing a challenge or a goal that changes their near-time life, launching them on a quest to solve the problem or attain the goal, with something opposing that objective (usually the villain, but sometimes a force; in either case, the story works best when that opposition is external rather than an exclusively internal demon), with meaningful stakes hanging the balance.

Brian Kiems, Confessions of a Story Coach

In a carnivalesque picture book there may be no opponent in this basic sense. The opponent may be the parent who has abandoned the child (by getting out of the way). The fantasy creature arrives on the scene and creates chaos (The Cat In The Hat) and encourages the child to have a lot of fun, sometimes by creating absolute chaos.

STEP FIVE: Plan/Fun Ensues, Hierarchy Is Overturned

Generally, the main character makes a plan. Writers are often told that the most engaging main characters take initiative. No one wants to see an unmotivated character. But in reality, some people don’t have much get-up-and-go, and some stories are about them. If your main character is a passive type, the opponent instead makes the plan. The main character reacts. Almost without exception, the sluggish main character will accept this ‘call to adventure’ and rise to the challenge at some point.

In longer stories like feature films or novels the initial plan falls flat, then the main character must change the plan a bit, or a lot, as things go increasingly wrong. In comedies, the plan is often totally ridiculous. We enjoy watching characters trying to carry these plans out. Trickster plans are also very fun to watch.

In a carnivalesque story the fantasy creature will initiate the action, though the adult reader may decode the story differently: The creature is a figment of the young child’s imagination, so technically came from the child. Children’s stories work differently at the ‘planning’ stage because young children don’t have the executive functioning to make plans, as such. They tend to roll with the circumstance or with their imagination. Plan is less useful as a concept in stories for young children. In that case we might call this phase “Fun Ensues”.

STEP SIX: Peak Struggle/Peak Fun

Most commonly, this part of a story is called the climax. But what does that really mean?

In a story aimed at adults or older children, the main character might kill off their old self. More rarely, they might choose not to change.

I think there are very few rules that can’t be broken. I think there is only one that is very difficult to break. I have seen it broken, but not very often. It’s that something has to change. From the beginning of the story to the end, something needs to be different. The only time I’ve ever seen it successfully broken was a Grace Paley story called “A Conversation With My Father.” But as a general rule, something has to change. There has to be some source of tension.

Mary Gaitskill

The main character far more often chooses to confront their innermost fears and overcome them. They are rewarded for that.

There’ll be a big struggle in every story. Not always a fisticuffs showdown, or a gunfight (though in certain genres that will definitely happen too. But there will be one big scene — arguments or extreme peril, or witnessing someone else have a fight, which the main character will have had a role in provoking. Importantly, the big struggle that you see on screen or on the page isn’t necessarily the big struggle that they’re fighting themselves. An adjacent fight scene may just exist to represent their own inner turmoil.

TV writers in the United States call this part of a story the ‘worst case’. BBC writers call it ‘worst point’. If it’s TV we’re talking about, on a commercial station, it’ll be the bit that happens right before the last commercial break. It’s also where TV writers leave the ending in continuing series, knowing the audience will want to come back to find out if the characters escaped ‘alive’ (metaphorically or otherwise).

Others call this stage the ‘crisis’. The worst happens to them. Bad things happen, worse things, now the worst. The crisis is a kind of death. It usually isn’t the main character who dies, of course. We want them to stick around for the next bits. The most dangerous thing to be is the main character’s best buddy (especially if the best buddy is Black). There’s a high mortality rate for those guys.

In Tragedy: Sometimes no one actually dies, but hope passes away. These stories are often pyrrhic victories.

Perhaps, if you think in terms of narrative climax, you’re wondering which part that would map onto. Think of the ‘climax’ as the bit where the main character finds release from their seemingly inescapable predicament. I’ll slot the climax in right between big struggle and new situation. ‘Climax’ is a useful concept in terms of criticism, but for storytellers? I prefer to think in terms of big struggle followed by new situation. The climax is what the audience feels. It’s not a story stage per se. The climax is the part which is the ‘obligatory scene’, set up by what some call the inciting incident. For instance, when Louise murders the rapist in the inciting incident of Thelma & Louise, the climax must be the confrontation between the women and the law.

STEP SEVEN: Anagnorisis

This Greek term is fairly broad and comprises two main parts:

- The main character learns something about the plot in what filmmakers like to call a ‘reveal‘.

- The main character may learn something about themselves.

Lyrical short stories, especially those we might call Impressionistic, often work differently. The Literary Impressionists didn’t think people really changed much. In Katherine Mansfield’s short stories, any new self-knowledge often takes place off the page. She liked to make use of the ellipsis or a scene break, so look out for those. Often, Mansfield’s main character learns nothing at all. But the reader may have. Chekhov, like Mansfield left out this part of the anagnorisis, hoping for the revelation to happen for the reader rather than for the character. In order for this to happen, the reader must put in some work.

Contemporary short story writers often end stories this way, too. Helen Simpson’s “In-flight Entertainment” is the perfect example of a character who comes so close to realising something then doesn’t. This is a story about climate change and people’s ability to ignore it. I can see why this type of ending is making a comeback.

The failure to learn anything about oneself or otherwise isn’t super rare outside lyrical short stories, but still unusual. We see it in Larry McMurtry’s Hud. We see it in Mad Men. Don Draper, frustratingly, doesn’t really change. But characters around these (ostensible) main characters do experience character arcs. We might instead ask of these stories who is the real main character? (Hud was renamed Hud to replace McMurtry’s Horseman, Pass By because Paul Newman as an actor was a selling point, not because the story itself is really about his character. Don Draper’s creator, Matt Weiner, has said that he doesn’t believe people always change with the changing times, and that was his main point.)

Where a character does learn something about themselves after coming close to death, the new self-awareness usually comes with suffering, especially in modern realistic young adult literature. where characters are really put through the mill, often in dystopian or traumatic settings. The young adult years accompany what Heidegger called ‘Being-toward-death’. We learn people die when we’re very young, probably before we start school. But we don’t fully appreciate the finality of our own lives until later — sometime in the teens and twenties.

A coming-of-age story features a main character who achieves a little bit of awareness but not so much that they could be considered completely self-aware and wise. No Awareness >> Growing Awareness >> Full Awareness.

Characters…should not always get what they want, but should — if they deserve it — get what they need. That need, or flaw, is almost always present at the beginning of the [story].

John Yorke, Into The Woods

Even in a Carnivalesque picture book, characters have got what they wanted and needed — fun and a little bit of freedom from the hierarchy of adults who rule their young lives.

Another Greek word may be useful here: Catharsis. Like ‘climax’, this word describes what the audience feels at this point rather than the structural component utilised by a storyteller. A storyteller may indeed aim for catharsis — a sort of spiritual cleansing, a release of strong emotion. I see catharsis as a subcategory of the anagnorisis. Revelation doesn’t always accompany strong emotion, but when it does, the anagnorisis becomes super powerful.

The word ‘epiphany’ is often used when talking about lyrical short stories.

“Do you believe in epiphanies?” she asks. We start walking again.

“Um, can you unpack the question?”

“Like, do you believe that people’s attitudes can change? One day you wake up and realize something, you see something in a way that you never saw it before, and boom, epiphany. Something is different forever. Do you believe in that?”

from Will Grayson, Will Grayson, by John Green and David Levithan

It was Joyce who coined the term epiphany when applied to literature. Before that it was a religious term, a divine manifestation (a sighting of god).

- An epiphany is a moment of insight which briefly illuminates the whole of existence.

- Epiphanies are usually invisible and private. On the outside, things seem pretty much usual.

- It is important that epiphanies take place inside the everyday, subtly altering the character’s perceptions, making time stand still.

Time often dilates in the epiphany sequence, compared to the pacing of the rest of the shot story.)

What about short stories? Do characters in short stories always need to understand something new about themselves or the world?

The classic story structure is based upon an assumption: That people go through life experiencing teaching moments, eventually achieving wisdom. But some writers don’t buy this at all. Instead they believe that people are never in full possession of the truth, because they are living in a fantasy world, because they are delusional somehow, because they don’t have full access to the facts, by virtue of being trapped and isolated within their setting.

EPIPHANIES MAY NOT LAST

For these characters, ‘epiphanies’ may be brief flashes of insight, preceding a return to comfortable delusion. Katherine Mansfield was all about this kind of story. Characters in impressionist works don’t have any special insight into anything, and it would seem contrived, and untrue to the mood of the story to suddenly let them achieve clarity at the end. So they often don’t. Because we expect characters to have an epiphany, the Literary Impressionist writer might seem as if they upped-sticks and plain old got jack of their story, leaving the reader high and dry. In order to understand a story like this, the symbolism is as important as the surface layer. It takes time to develop this particular reading skill. Back to the first point, all characters in an Impressionist work are unreliable, because the theme is that no one can possibly be reliable.

As mentioned above in regards to Impressionist and Modernist short stories, it’s certainly not the case that short stories are all about ephiphanies whereas other forms of stories feature hard-won insight, but the truncated form of a short story means that, where a character does achieve new insight, it has happened very quickly.

HOW IS THE SHORT STORY EPIPHANY DIFFERENT FROM THE ANAGNORISIS OF A LONGER WORK?

In a novels, TV series and films if none of the characters have some sort of anagnorisis the audience will get the sense that their time has been wasted, that the story hasn’t ended properly. They won’t necessarily be able to articulate why they feel this way, but they’ll feel it.

Readers of lyrical short stories come with different expectations, or rather, without the same expectations. (Hence: the paratext is the vital first step.) In real life, not every moment teaches us something. Sometimes it should, but still doesn’t.

THREE TYPES OF EPIPHANIES IN FICTION

- The reader comes to understand something but the viewpoint character does not.

- The viewpoint character comes to understand something and so does the reader, if the reader interprets the story in a certain way, and if the reader is ready.

- The character thinks they’ve had some kind of epiphany but they’re wrong. This creates an ironic distance between the character and the audience, because the audience will realise they are wrong.

New Situation/Return To Home

In children’s stories, where home is important for a child’s psychological safety, the young character almost always returns home, and oftentimes things are exactly the same as before. Bedtime as usual. Mythic stories for children are therefore commonly called Home-away-home stories.

Even an adult audience generally needs a scene or two in which they get a glimpse of how things are going to be from here on in, though sometimes writers offer a truncated story, leaving out this bit, so the audience can decide for themselves what happened.

Lyrical short stories work differently. Lyrical short stories rely heavily on symbolism. Oftentimes, if an ending feels ‘left out’, that’s because the reader is expected to interpret the symbolism and imagery and piece the ending together like a jigsaw puzzle. Stories which expect much from the audience are commonly called open endings.

EMOTIONAL CLOSURE IS NOT THE SAME AS NARRATIVE CLOSURE

The new situation phase of a short story sometimes feels absent. What’s actually happening is that the reader is left to extrapolate the New Situation.

I have written an entire post on Short Story Endings and Extrapolation. To summarise, though:

In the image-based story, the ending may feel open. The story may end on the image most central to the story, creating emotional closure but not necessarily narrative closure.

STEP EIGHT: Extrapolated Ending

This step doesn’t apply to all stories and relies on audience participation.

Not all stories are designed to resonate. Sometimes, the audience leaves the story and never thinks about it again.

But the most important stories leave the audience thinking about something. In this case it’s up to others to work out what happens next. This isn’t going to be a scene as such, but an accumulation of details garnered from all the scenes which lead us to our conclusion.

LYRICAL SHORT STORIES SOMETIMES END ON AN IMAGE

Sometimes a lyrical short story ends on an image which cannot be fully explained. Nevertheless, the story has ended on the image for a reason – not on some random thought or observation. For example, in “Bliss“, Katherine Mansfield ends with the image of the pear tree. The pear tree hasn’t changed at all, juxtaposing against Bertha’s extreme change in emotional valence. That is what readers are left to extrapolate: Bertha no longer feels blissful. Why not? Well, that’s up for debate.

STEP NINE: Resonance

If storytellers have ‘cheated’ a bit, the audience may experience what Alfred Hitchcock called a refrigerator moment. “Hang on a second, that didn’t make any sense…” (So named because these thoughts occur only after leaving the story and grabs a drink from the fridge.)

Refrigerator moments are okay in stories meant to be viewed once then forgotten. But in resonant stories, the period after the story expands the narrative in the audience’s head. The story becomes integrated into their very real lives. A real life moment may remind them of a fictional one.

Try, if possible, to finish in the concrete, with an action, a movement, to carry the reader forward. Never forget that a story begins long before you start it and ends long after you end it. Allow your reader to walk out from your last line and into her own imagination. Find some last-line grace. This is the true gift of writing. It is not yours any more. It belongs in the elsewhere. It is the place you have created. Your last line is the first line for everybody else.

Colum McCann

Story resonance most likely occurs when:

- The audience identifies with one or more of the characters (that doesn’t mean they necessarily like them)

- The audience identifies with the situation, and compares their own decisions to decisions made by fictional characters

- Symbolism set up by the storyteller hits the audience at a gut level

- In his book Black Swan, Nassim Nicholas Taleb notes that metaphors and stories are far more potent than ideas. They are also easier to remember and more fun to read…ideas come and go (unfortunately) but stories stay. In other words, resonant stories are memorable ones, structured according to univeral ‘story rules’ rather than expressed as ideas. Memorable stories are often the most simple.

This explains why resonance is independent of length. A short story or poem can be as resonant as a feature film, or a novel of 1000 pages, because complicated plot is immediately forgotten. Picture books are excellent for conveying ideas hidden within memorable story because the structure is so clean.

Although a storyteller does not have full control over how much any given audience member is prepared or able to bring to the table, the above steps, combined with resonant imagery and universally accepted structure, go a long way towards controlling (or guiding) audience reaction.

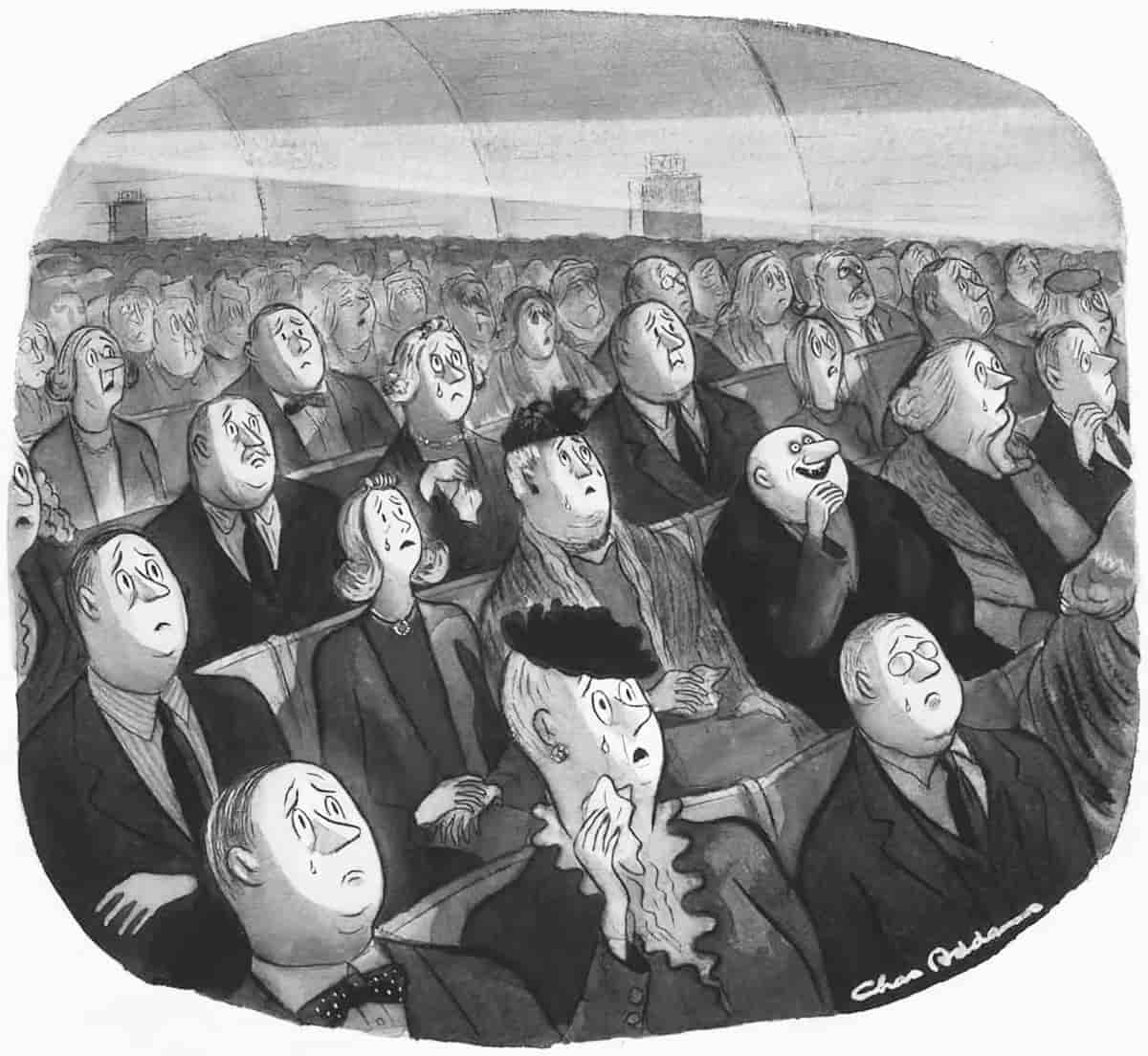

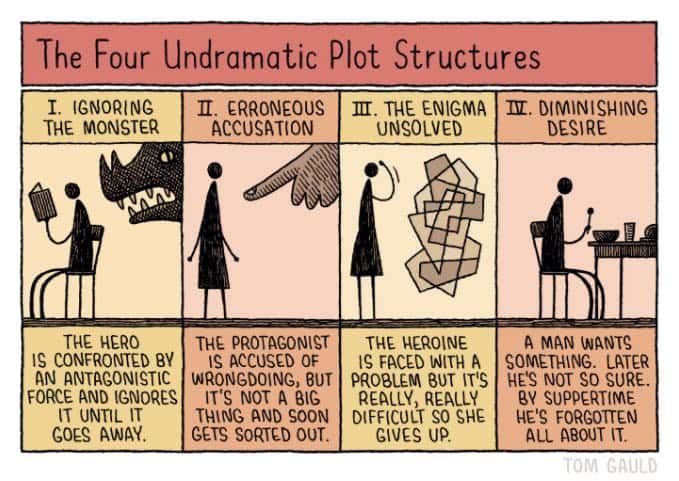

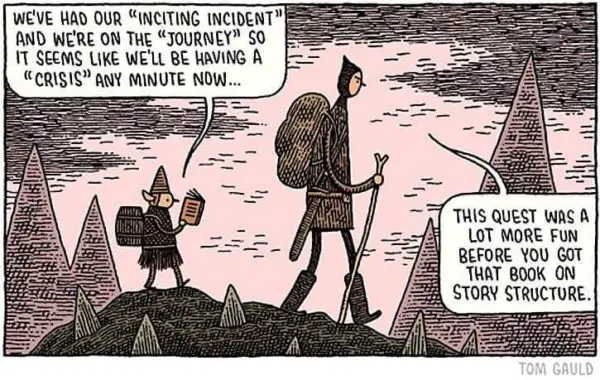

Below, Tom Gauld riffs on these widely shared rules. Here is one of his New Yorker comics:

Box one shows that a main character must take action otherwise it’s not a story.

Box two shows that there must be conflict otherwise it’s not a story.

Box three shows that the main character must constantly redouble efforts (and modify plans) in order to achieve the goal.

Box four shows that a main character needs a strong desire.

The W-question Method

Jason Katz of Pixar fame advises storytellers to ask the story questions in the right order.

Katz orders his answers to those questions as follows: who, when, where, what, why, how. According to him, the “who, when, where” is easy. That’s where you’re establishing the setting for your story and identifying your main character. He goes on to say that answering the “what” is the thing that will drive your story. He calls it the “engine of your story” and one of the critical steps to answering the “what” question is asking two more: “what does your character want?” and “what does your character need?”

No Film School

Header image: Haynes King – The Letter 1872

The East Asian Four-Act Structure

Writer Henry Lien explains that this structure is common in Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, and Japanese storytelling.

Koreans call it Gi seung Jeon Gyeol ( 기승전결)

In the West we have borrowed the Japanese word: kishōtenketsu.

Act One — Kiku (起句), きく — Introduction of the Main Elements

Act Two — Shōku (承句, しょうく) — Development of the Main Elements

Act Three — Tenku (転句, てんく) — Twist (New Element)

Act Four — Kekku 結句, けっく) — Conclusion (Harmonizing of All Elements)

HOW EAST ASIAN STORIES ARE DIFFERENT FROM WESTERN STORIES

- Western stories are all about conflict, tension and a tidy resolution, unless we’re talking about Postmodern works and lyrical short stories. In that case, audiences don’t expect endings to provide everything on a plate. Readers will expect to do some work.

- We might say East Asian audiences ‘do conflict’ differently. East Asian stories are “more interested in exploring the unseen relationships among the story’s elements than in pitting them against each other.” (Henry Lien)

- Western stories are often thought to be symmetrical, with a big turning point at the centre, sometimes conceived of as a three act structure, with the end linking into the beginning somehow.

- East Asian stories build gradually. If Western audiences don’t get foreshadowing, they feel cheated, as if the storyteller has ‘sprung’ something on them. But East Asian audiences happily accept new elements introduced late, sometimes in Act Three. Even a children’s story such as Totoro doesn’t introduce the monster Totoro until late. Nor was there any foreshadowing. Hollywood doesn’t make children’s films which do this. We sometimes find this in older Hollywood stories such as Alien, but there is plenty of foreshadowing. Everyone is expecting an alien, right?

- The fourth act of an East Asian story “harmonizes” all the elements that came before. In the West we think in terms of happy endings (not as common as we think, not even in Hollywood) but harmonize is a more apt word for East Asian endings. Act Four “contains a revelation about the relationships among the elements that often feels like a new element in itself.” (Henry Lien)

- If you use kishotenketsu, you don’t have to worry about Deus ex machina, because it’s really, really hard to make a good kishotenketsu and pull off a Deus Ex machina, because the center isn’t conflict, but realization and development. (Kim Yoon Mi)

- Western storytelling has been influenced by writers such as E.B. White and Russia’s Chekhov, who said this: Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”