Daniel Handler wrote the teleplay (as well as the books) to the Netflix adaptation of A Series Of Unfortunate Events. The author’s voice and politics come through loud and clear.

Handler loves wordplay, and is not shy of delivering a ‘moral lesson’ on the difference between ‘literally’ and ‘figuratively’. Words and their meanings are consistently explained, but because Klaus, at least, already knows what the words mean, the young viewer does not feel condescended to. The joke is almost always on Count Olaf. Handler also has a keen handle on the most common storytelling tropes in children’s literature, and makes fun of them whenever he can. Lemony Snicket is on the side of the child.

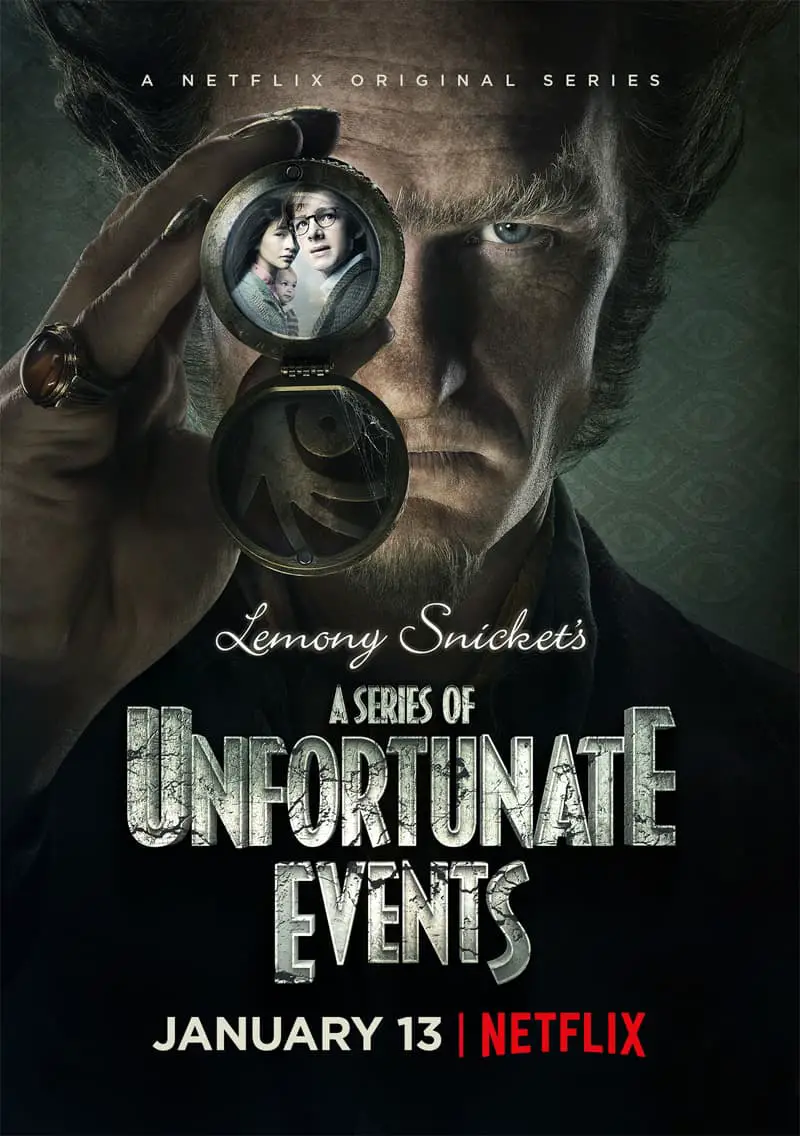

In the books the storyteller is hidden from view, but for the television series Lemony Snicket is portrayed in the form of Patrick Warburton, whose formal dress juxtaposes with the humorous positions he is placed in: sitting on a lifesaver’s chair, coming out of a sewerage hole in the middle of the street and so on. See: The Role Of Storytellers In Fiction.

A Series Of Unfortunate Events is famously metafictive, in which a character called Lemony Snicket warns children that this is going to be a terrible, horrible tale and they’d best turn away. Tongue-in-cheek reverse psychology. This advice is taken to its metaphorical limit in the TV series, in which the theme song advises us to ‘look away, look away!’ Then we have all the eye imagery — the viewfinder views, Count Olaf’s gaze through the peep hole (the first the Baudelaire children see of him), his eye tattoo and so on.

The cinematography of the Netflix TV series seems influenced by the films of Wes Anderson, both in symmetry and in colour. An audience knows to expect quirky from this style, and dark humour. (It was filmed in British Colombia, Canada, and you may recognise an actor or two from Orphan Black.)

The brother and sister Baudelaire children stand in for ‘The Everychild’. They do not have all that much in the way of personality, aside from being inherently good and kind and well-behaved. There are differences between them — while I read Klaus as an autist, Violet is a comically Pollyanna character, determined to make the most of the situation when she asks Klaus to come across the worst predicament he’s ever encountered in his reading, then concludes they are not so badly off. Again, this is Daniel Handler making fun of the character trope that girls and boys in popular children’s stories are expected to be ‘nice’ and ‘good’. This doesn’t matter — we have Count Olaf for the laughs. In fact, all of the surrounding characters have more quirks and personality than Violet and Klaus, who, like the child audience, are newcomers to the situation and are to be read as ‘normal’.

The baby has magic super powers — she can chew things to pieces, and even create entirely new objects simply by using her four teeth. Her baby language is treated as if it’s an entirely different language, which only her siblings and surprising other characters are able to understand to the exclusion of everyone else. The baby’s words are subtitled in a font from the silent film era.

This setting is an example of Magic Realism. It also has steampunk elements, not so different from the Spy Kids series, in which our child heroes are expert at building contraptions. These expertise are first shown as a means of them having fun (retrieving the perfect skimming stone from the ocean), but of course these skills come in handy later, to get themselves out of dire trouble.

“It’s only scary because of the mist,” Klaus says metafictively, as Mr Poe (surely named after the horror writer?) approaches them on the beach to deliver terrible news. See: Fog Symbolism.

A lot of the humour comes from the juxtaposition between the fairytale setting and very modern problems. For instance, when Hook-Handed Man ruins an old-fashioned typewriter (because he has hooks for hands) he asks for IT support. When Count Olaf says Violet will be marrying him ‘in an hour’ he upends a giant hourglass which he can’t remember the name of. This is making use of the classic ‘ticking clock’ storytelling device, often used to heighten suspense, but when the timer runs out nothing happens, except for Count Olaf losing face by returning through the trapdoor of the attic to explain that, actually, he bought the thing online and he didn’t know the sand went through so quickly so the children will have to turn it over a few times.

Handler is a master of irony, and there is irony in every scene and in a large proportion of the dialogue. For example, the Baudelaire children are at first taken to Mr Poe’s family — an archetypal cosy house with both parents, full of children and a well-coiffed mother in an apron who at first appears to be the epitome of a caring 1950s housewife.

We soon learn, however, that not all is well in the suburbs and she is in fact unwelcoming, taking obvious and great pleasure in the publicity she is able to garner for her own family via this tragic event.

Later that night, her children ask the Baudelaires how they managed to kill their parents, presumably because they’re hoping to do the same. The following morning we see just how small and ‘cosy’ the Poes’ house really is. Small-minded people live in very small houses — ‘cramped’, more than ‘cosy’, as first suggested by the dining table scene.

This ironic tone pairs very nicely — like a great pair of serif/sans serif fonts — with the fact that much of the dialogue is in fact ‘on the nose’. The plot itself is signposted. While we are busy enjoying the setting and humour, we are not expected to work too hard to understand what is going on.

Daniel Handler is firmly on the side of the child audience.

Mr Poe: “I know you must be nervous about living with a guardian. I know how I was when I was your age.”

Klaus: “We’re all different ages.”

The joke is repeated again later when another clueless adult — Count Olaf — talks about how much he loved cupcakes when he was ‘their age’. Again, Klaus repeats, “But we’re all different ages.” As is the child audience. More proof that in Daniel Handler’s writer’s mind, the Baudelaire children stand for The Audience In General. Also, we are not to believe adults who use the annoying phrase, “When I was your age”.

When Klaus expresses dismay at Count Olaf’s having a tattoo of an eye on his ankle (not to mention all the obvious eyeball paraphernalia about the house), the very reasonable and politically correct Violet advises her brother, as well as the audience, that tattoos are simply a decorative pigmentation of the skin and do not mean the person wearing them is bad. This stands in stark contrast with much characterisation from The First Golden Age Of Children’s Literature in particular, in which we were actively encouraged to judge baddies based on what they look like.

A mystery is introduced when the children find a strange object hidden in the rubble of their family home.

Cinderella is the ur-tale behind A Series Of Unfortunate Events. We have poor orphans who have lost their caring and excellent real parents and who are sent to live in a big house which is emotionally bereft. They are forced to endure terrible hardships, though not of the realworld kind — that would be too cruel and not at all for children — cleaning and scrubbing and cooking and always failing to win approval. Basically an exaggerated form of how generally-cared-for children feel when they’re feeling a bit sorry for themselves.

Why is it not more tragic that the parents (apparently) die in a terrible fire right at the beginning of the story? Because we don’t know the parents. The history of children’s literature (particularly American children’s literature) is chock full of orphans. If we don’t get to know them, their deaths are not sad per se, rather the plight of the children is the sad thing. See: Why So Many Orphans In Children’s Literature?

The dark, empty mansion belonging to Count Olaf is contrasted with the inverse living right across the road — Justice Strauss who is not the slightest bit evil, has a garden full of blossoms, a beautiful big library and is a very caring person. Extreme evil against extreme nice. Comic characters are often 2D and that’s just fine. These are dream houses, to use the terminology of Gaston Bachelard, so of course they have stairs, basements and attics. See: Symbolism Of The Dream House.

When the camera pans from Justice Strauss’s house to Count Olaf’s gothic mansion the camera follows a blue bird flying happily. Unfortunately, in the middle of the street, a raven swoops down and kills it. A raven in storytelling probably puts you in mind of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem, among many others. The raven is a metaphor for death, understood by young audiences and jaded ones alike.

It’s such a shame the Baudelaire children can’t live with Justice Strauss, and we are made to feel it keenly. This regret is underscored by her declaration that she’s just bought a new food processor, but who does she think she’s kidding because “I have no mechanical skills whatsoever”. Since we already know the children are expert mechanics, they would obviously be a great fit. Moreover, she has no way of cutting up the baguette, which the baby is excellent at doing with her teeth.