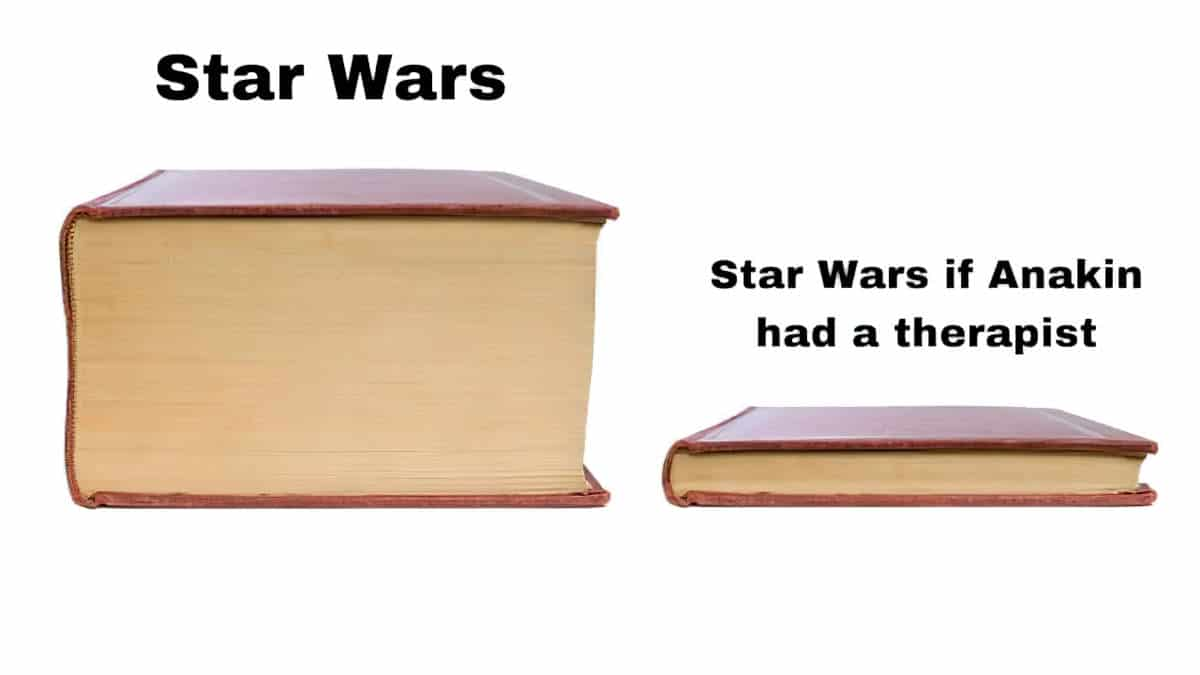

Most writers are well-aware that a main character needs a shortcoming. Christopher Vogler and other high profile story gurus often talk about a lack:

It can be very effective to show that a hero is unable to perform some simple task at the beginning of the story. In Ordinary People the young hero Conrad is unable to eat French toast his mother has prepared for him. It signifies, in symbolic language, his inability to accept being loved and cared for, because of the terrible guilt he bears over the accidental death of his brother. It’s only after he undertakes an emotional hero’s journey, and relives and processes the death through therapy, that he is able to accept love.

Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey

First, there’s the issue of the Hero’s Journey as an ideology: One issue with the “Hero’s Journey”: its insistence on individualism v. collective strength and community. Yes, the “hero” has help but those who help are relegated to the side, their purpose mostly reduced to further the hero’s goals, often at the expense of others.

Tricia Ebarvia

Aside from that, Vogler’s advice does not go far enough. Go one step further and break it in half.

Everyone who gives writers advice about characterisation has something to say about this topic. Author of the book Story Genius Lisa Cron says that it’s the character’s internal struggle that makes the external struggle important.

What about children’s books? Do they follow the same rules?

Mostly, but not always. Some picture books do not feature characters with shortcoming. These stories tend to be of the carnivalesque variety. A few standout examples feature the reader as main character. These postmodern meta examples do not follow the general rules of story.

Children’s books for older readers do follow the same rules as those applied to narrative aimed at adults. Modern picture books which win big awards are also likely to follow these rules.

CHARACTER SHORTCOMING

I’ve seen plenty of students come in and say, I want to write a novel about blah blah blah. But you just can’t do it. You can only write a novel about a character who does something wrong, and see what happens from there. Novels are compendiums of bad behavior, and literature is the gossip about it.

Ethan Canin

Beautiful Mess Effect: We tend to view our mistakes & vulnerabilities with shame because we think they make us look unappealing. But research suggests our mistakes & vulnerabilities actually make us more relatable and endearing to other people. So don’t be afraid to be human.

@G_S_Bhogal

According to the rules of story structure aimed at screenwriters and writers with an audience of adults…

Every Main Character Needs…

- A PSYCHOLOGICAL SHORTCOMING: What are the fundamental flaws?

- A MORAL SHORTCOMING: How does this character treat others badly? (Lacking empathy, overbearing, two-faced, greedy, lying, selfish etc.) The Seven Deadly Sins feature prominently in this part of the shortcoming.

Sometimes students seem shy about writing about people who do the wrong thing — we’re all taught to do the right thing and focus on the right thing. But all of literature is about people who do the wrong thing, despite themselves. What would the story be if they did the right thing? No story at all. Fiction wants to look at all the things that go wrong.

Chang-Rae Lee

HAMARTIA

Aristotle had a similar concept and called it ‘hamartia’:

Hamartia is a term developed by Aristotle in his work Poetics. The term can simply be seen as a character’s

Wikipediaflaw orerror. The word hamartia is rooted in the notion of missing the mark (hamartanein) and covers a broad spectrum that includes accident and mistake, as well as wrongdoing, error, or sin. In Nicomachean Ethics, hamartia is described by Aristotle as one of the three kinds of injuries that a person can commit against another person. Hamartia is an injury committed in ignorance (when the person affected or the results are not what the agent supposed they were).

A COMMON MISUNDERSTANDING OF THE WORD HAMARTIA

But the word ‘flaw’ in that definition can lead to misunderstanding for people familiar with the term ‘fatal flaw’. ‘Fatal flaw’ is a phrase coined by English literary scholar A.C. Bradley. Aristotle’s hamartia refers specifically to a character’s error of judgement. Importantly, hamartia refers to a character’s actions, not to something within the character themselves.

Shortcomings In Character Archetypes

Like anything, this ‘rule’ that characters require a weakness has developed some tropes. As an example:

Common Shortcomings of Young Women

This trope comes from the Gothic tradition.

The story of the poor girl who overcomes obstacles and makes a good marriage in the end, what might be called the Horatia Alger story, is very common in nineteenth-century fiction, especially fiction written by women. This heroine does not have to begin in absolute poverty — even Cinderella’s family must have been middle-class or her stepsisters wouldn’t have been able to go to the ball in such style. But she does have to be in some way underprivileged at the start of the book, and she must go through many difficulties before she can marry the prince.

Occasionally she is poor in other than the economic sense, as with some of Jane Austen’s heroines: Catherine Morland of Northanger Abbey is poor in intellect; Marianne Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility is naïve and muddleheaded; while Fanny Price of Mansfield Park is … poor in spirit. Charlotte Bronte, even more daring, made the heroine of Villette plain.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The power of subversive children’s stories

The shortcoming of being ‘plain’ continues to be explored in young adult fiction today, as beauty privilege continues to be a thing in modern society.

An Outdated Way Of Showing Character Shortcoming

In the simple thriller form the antagonist is marked out by their desire to control and dominate the lives of others. They don’t follow the moral codes of the community; more often than not they’re an embodiment of selfishness. They are also, historically, often marked by physical or mental deformity. Le Chiffre’s maladjusted tear duct in the film of Casino Royale is the modern equivalent of Dr No’s missing hands or Scaramanga’s third nipple in the Man With The Golden Gun. In a more politically correct age, the physical flaw (clearly an outer manifestation of inner damage) has been scaled down to a level society finds acceptable. If the antagonist is internal, the same principles apply: the enemy within works in opposition to the host’s better nature — it cripples them. It stands in opposition to everything they might be.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

BEWARE: AVOID USING DISABILITY AS NARRATIVE SHORTCOMING

As mentioned above: The two-fold shortcoming required for a good story is psychological and moral. A shortcoming that exists as a result of disability is not what we’re talking about here.

One of the reasons own voices stories are so important: Too many writers are making use of a disability as a shortcoming. Most people will recognise when a writer is falling into this trap with physical disability, but like invisible disabilities themselves, most people don’t seem to recognise it happening when invisible disability is used as a narrative shortcoming.

What if a blind person’s blindness were used as their shortcoming? What if a wheelchair user’s inability to walk up stairs were used as their narrative shortcoming? The ideological problems are far easier to pinpoint when the disabilities are obvious to outsiders.

To spell out the ideological issues in the clearest way I know how: In a story, a main character’s shortcoming will be challenged over the course of the story. The main character will either grow or not (in the case of a tragedy). The reason disability cannot work as a shortcoming: A disability is a part of someone, often part of someone’s identity, and is not something to be overcome, and not something tragic if it’s not ‘overcome’. Nor is it okay for one character’s disability be used as the basis for another character’s arc.

We have only one story. All novels, all poetry, are built on the never-ending contest in ourselves of good and evil. And it occurs to me that evil must constantly respawn, while good, while virtue, is immortal. Vice has always a new fresh young face, while virtue is venerable as nothing else in the world is.

John Steinbeck, East of Eden

Character Shortcoming and Romanticism

The Ancient Greeks thought of love differently from how we do today. The Ancient Greeks thought that love was an attraction to virtue, perfection and accomplishment.

Then the Romantics came along and changed storytelling from the middle of the 1800s onwards. We are still living under the ideas of the Romantics today. Romantics believe all sorts of misguided things about love, and one of them is that each of us has a soul mate, a perfect match for us, and once we find that person and get together with them, true love means we never criticise each other and find the ability to gloss over each other’s shortcomings. Therefore, to criticise one’s spouse is considered the inverse of love, which it’s really not at all. It means we care enough to criticise them, and feel safe enough, within our mutual love, to do so.

It seems to me that modern love stories oftentimes straddle those two notions of love. The heroine and love interest in a romance genre story will each be given shortcomings, sure, but only ‘fake’, adorable shortcomings.

The willingness to please, a tendency to clumsiness, a sardonic sense of humour. That sort of thing.

Do Children’s Book Characters Need A Moral Shortcoming?

Or any shortcoming at all?

The short answer is that, yes, an interesting modern children’s book character needs at least a psychological shortcoming, and the story might also support a moral shortcoming. This wasn’t always the case, as you’ll already know if you’ve read from the First Golden Age Of Children’s Literature. It was the amazing Edith Nesbit who changed all of that.

All of Nesbit’s characters have both virtues and flaws: not only are the children’s actions always a push and pull between their better instincts and their baser impulses, but the various authority figures they encounter are equally complicated. The magical Psammead creature is peevish, the Queen of Babylon is kind-hearted but imperious, and the upstairs scholar is helpful but blind to the magic he experiences.

The Toronto Review Of Books

Until Nesbit came along, adults who wrote for children believed children read stories as medicine. The viewpoint characters therefore had to demonstrate impeccable behaviour, or else be punished for wrongdoing, learning to be good along the way.

Perhaps a better way of wording this storytelling requirement: Children in stories shouldn’t always ‘do the right thing’.

[Julia] Donaldson’s books are not for children’s benefit, but their enjoyment. “Her stories are never twee,” [David] Walliams said. “There is often real danger, and her characters don’t always do the right thing. The result is that the books are proper page-turners.” The quick-witted hero always bests the villain, the brave snail/fish/stick overcomes great peril to find their way home.

The Guardian

Must Children’s Book Characters Treat Others Badly?

After looking at a lot of children’s books with this exact question in mind, the answer is no. There are several reasons for this:

- Some characters in children’s books represent the Every Child. When a reader is meant to paste themselves onto the character we don’t want that character to be too specific. For similar reasons a lot of picture book characters are cartoon-like and minimalist. (For more on that see Taxonomy Of Detail In Character Illustration.) Even in stories for older readers, these Every Child characters are given a ‘cosmetic’ shortcoming rather than a psychological and moral one, which makes them far more generic and less interesting. For instance, a common cosmetic shortcoming in young adult romance is ‘clumsy’. Bella Swan is one example. Even in stories for adults you’ll find the Every Man. Susan from Desperate Housewives is clumsy but this clumsiness functions to provide comedy. Susan has many other psychological shortcomings. She is unconfident and needy but also fake-nice and backstabbing. Susan’s clumsiness has nothing to do with storytelling.

- There are gatekeepers of children’s literature — people responsible for buying the books and putting them into children’s hands — who choose literature with the philosophy that characters in stories need to serve as role models for good behaviour. These people might approve of characters who treat others badly but only if that character is punished. For more on that see Picturebook Study: In Which Baddies Get Their Comeuppance.

- The wish to avoid child characters as morally corrupt may derive from JudeoChristian thought. It is believed people enjoy an ‘age of innocence’. Strictly speaking, we’re better off using the phrase ‘age of accountability’ because the Bible does not suggest at any point that children are sinless, but rather that children can’t be held accountable for certain things due to their inexperience. Thirteen is the most common age suggested for the age of accountability, based on the Jewish custom that a child becomes an adult at the age of thirteen. This is no doubt related to The Magical Age of 12 in children’s literature. (There’s nothing in the Bible, however, to suggest thirteen is a significant age.)

- Complex, rounded characters simply aren’t necessary in all types of stories. For action stories with exciting plots, or genre fiction — such as mysteries and thrillers — all the reader really wants is a great story. In fact, the characters can’t change all that much if the book is part of a series. Series fiction is very popular with young readers and the best-selling books are all part of a series, year after year.

The view that badly behaving children’s characters must be punished is increasingly challenged, mostly by writers and publishers who refuse to believe in the concept of the young reader as tabula rasa (blank slates), who trust children and young adults to read critically and not blindly follow their main characters into bad situations. The modern main character in children’s stories will most definitely have both a psychological shortcoming and a moral shortcoming. In other words, they will be treating others badly in some way.

This wasn’t always the case, and if you take a look at books from the First And Second Golden Ages Of Children’s Literature you’ll find many more Mary Sue/Pollyanna types, who have been written as model children for young readers to emulate. These characters are not well accepted by contemporary young readers.

The idea of child readers as tabula rasa was particularly strong in the Victorian era, and if young readers didn’t want moral stories they really only had the Gothic to turn to. These stories offered all the bloodshed, villainy and titillation lacking in the ‘stories for children’.

Not all writers of children’s stories are interested in this concept. Hayao Miyazaki has never formally studied screenwriting or storytelling technique, and goes about creating his Studio Ghibli films in his own auteur fashion. Miyazaki’s main characters don’t tend to have a strong external desire. He doesn’t bother with that. They do have psychological needs, however, and by the end of the story they haven’t necessarily got anything they wanted — but by immersing themselves in a new world, they have grown emotionally.

For this reason I feel the very concept of desire is a Western one. In Japanese language, to say “I want” something is considered childish and you’ll rarely hear those words (even though the grammar and words for desire exist). Instead, a Japanese interlocutor will avoid the assumption that you are a spoilt baby with desires and ask you what you ‘need’. English: “Do you want a drink of water?” becomes “Do you need a drink of water?” I believe Hayao Miyazaki brings his specifically Japanese sensibilities towards ‘desire’ to the table when creating his main characters — Chihiro doesn’t seem to want anything in Spirited Away — she is simply there, and if she works hard, things will come good. Desperately wanting to turn her parents back into humans would probably work against her cause.

Common Character Shortcomings In Children’s Books

They may be common but that doesn’t mean you can’t keep using them:

- Naivety. This is arguably the biggest shortcoming any children’s book hero has. It’s a good one, too, because the child can’t help it. Failure to understand the world is an easy shortcoming to improve upon over the course of the story, providing ample opportunity for a character arc. Hence, every story is a coming-of-age story.

- Cheekiness. These characters are fun to be around. They won’t let horrible adults get away with treating kids badly without at least a little backchat. Judy Moody.

- Talking too much/getting distracted. In short, developing executive functioning. Anne Shirley grew up in an age when children should be seen and not heard. There are many modern Anne Shirleys, always getting into trouble but adorable nonetheless.

- Shyness. Then you have your socially anxious characters who don’t find themselves in trouble with authority but who must learn to stand up for themselves and others, and for what they truly believe in.

Below are some modern and not so modern case studies of shortcoming and desire in (Western) children’s literature.

That said, the most popular, award-winning, beloved contemporary picture books for children often feature characters with a moral shortcoming.

- The fish in This Is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen full on steals someone else’s item of clothing. (Bear in mind that he is punished pretty heavily for it… behind the reeds.)

- The boy in This Moose Belongs To Me by Oliver Jeffers wants to deprive a wild creature of its autonomy. Who Wants To Be A Poodle I Don’t by lauren child is similar in that the adult character/child stand-in is not letting her pet dog behave like a dog.

- Millie by John Marsden and Sally Rippin stars a girl who doesn’t listen to her parents.

- Wolf Comes To Town by Denis Manton is an example of a baddie wolf who is in essence a serial killer. Guess Who’s Coming For Dinner? by John Kelly and Cathy Tincknell is similar but better known, for having won a big award.

- Pig the Pug by Aaron Blabey stars a selfish dog who hogs all his toys, contrasted with the caring, sharing Trevor.

- In some of the older types of stories, the main character sometimes gets into bother by failing to follow the rules set down by the parents. The Story About Ping by Marjorie Flack and Kurt Wiese is a good example of that. Today, failing to obey rules/parents/teachers is not considered a moral shortcoming. Rather, we’re in a period where we glamorise and encourage independent thinking and questioning of authority, of which I generally approve, except a lot of these stories also seem to punish those characters who do do as they’re told. (Usually nascent Hillary Clinton types.)

Psychological shortcomings are also common:

- The bear in I Want My Hat Back is ridiculously unobservant (i.e. stupid). Rosie’s Walk is the grandmother of this kind of story.

- Mog The Forgetful Cat by Judith Kerr — the psychological shortcoming is in the title.

- Wolves In The Walls features a child character who is anxious/scared. This is the psychological shortcoming of pretty much any monster picture book. The Dark by Lemony Snicket and Jon Klassen is a monster story which doesn’t mention monsters.

- Z Is For Moose by Kelly Bingham and Paul O. Zelinsky features a moose who basically throws a temper tantrum because things don’t go his way. Max of Where The Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak is another child who faces his own temper, though in a completely different kind of story.

- Sometimes the psychological shortcoming is one of the ‘high level’ ones, from the seven deadly sins. The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle is greedy and gets a sore belly.

Even in children’s books, the most interesting and beloved characters do have both kinds of shortcoming. This character isn’t necessarily the viewpoint character.

- Scarface Claw by Lynley Dodd —Scarface is mean to the dogs but this particular story shows us that he is also a scaredy-cat underneath.

- Olivia by Ian Falconer is basically a narcissistic little girl in a pig’s body. While I personally have no love for Olivia, she is very popular. (She’s much more appealing than her parents.)

THE RISE OF THE ANTIHERO

When main characters (heroes) have very clear and reprehensible moral shortcomings, we then call them ‘antiheroes’. In recent times, stories with antiheroes have proved very popular with audiences, notably in prestige TV.

Howard Suber in his book The Power Of Film argues that there is no such thing as an antihero, only those who act heroically and those who do not. Another problem is with the misleading name. Suber has noticed the word ‘antihero’ suggests a character who is ‘anti’ (against) the hero, but this is not what it means at all. Characters called ‘antiheroes’ are ‘not yet heroes’.

Christopher Vogler has said the same thing:

Definition of Antihero

Anti-hero is a slippery term that can cause a lot of confusion. Simply stated, an anti-hero is not the opposite of a hero, but a specialized kind of hero, one who may be an outlaw or a villain from the point of view of society, but with whom the audience is basically in sympathy. We identify with these outsiders because we have all felt like outsiders at one time or another.

The Writer’s Journey, Christopher Vogler

Perhaps Suber and Vogler would prefer the term ‘unhero’, though the unhero is a comic character and doesn’t tend to rise above his ordinariness:

The un-hero is most similar among the types of heroes to the everyman, with a key exception: he rarely ends up being a proper hero. Generally, the un-hero is in all the wrong places at all the wrong times and does more to hinder the cause of good/justice/world-saving than to help it. Somehow though, through cosmic confluence or the intervention of a more traditional hero, everything works out in the end and the un-hero is heaped with the credit.

This is generally a less serious heroic form and should be reserved for a less serious work.

J.S. Morin

The Function Of The Antihero

Antiheroes are fun to watch. We get to see characters breaking boundaries we’ve fantasised about breaking in our own lives. A lot of the time, antiheroes have the witty comebacks. They are ace with a handgun, always prepared and very organised. These people would actually make great workmates if they were working on the side of good.

In thematic terms, antiheroes play another role. By transgressing social norms and legal boundaries they ask the audience to reflect upon what is okay and what isn’t okay. Breaking Bad did this very well, though I believe the writers overestimated the reflective powers of a vast majority of their viewing audience. If you’ve seen Vince Gilligan interviewed, you’ll know that he expected his audience to stop siding with Walt and take the side of characters such as Skyler after a while. This didn’t happen for much of the audience, who are like ducklings, falling in love with the first character they are encouraged to bond with. Breaking Bad and the discussion that happened online around that time, with much hatred directed towards the character of Skyler, and to the actress who played her, offers insight into the Duckling Phenomenon.

A Brief History Of Storytelling That Lead Us Here: To The Age Of The TV Antihero

In the 19th century, you maybe spent an hour a day reading a novel, two hours a month watching a play. That was all the storytelling done by professionals for you. People now see that much storytelling every day. Theater became Broadway, then radio, movies, and TV. It all happened in the 20th century.

All the arts in the 20th century exhausted themselves technically. By the time Ad Reinhardt painted a canvas black from edge to edge and said it’s a painting, the form was over. Music had been explored down to noise. Every technical possibility had been explored. All possible techniques.

So I was thinking, Since all the arts have reached the black canvas, what was going to become of story? Where would writers go in the 21st century?

I realized there is one aspect of human nature that really hasn’t been exploited and explored: evil. You have dark characters like Iago, great villains who are diabolical and evil, but it’s a pure evil. Human beings are very rarely pure evil, and storytelling hadn’t truly explored the complexity of realistic evil.

And then, a few years later, came all these great long-form series, which opened an exploration of evil. There was The Wire and The Sopranos and Breaking Bad, even Mad Men. With all these great series, you get complex, good/evil characters.

Robert McKee in a Vice interview

Rise of the Female Antihero

When storytelling gurus talk about antiheroes, you’ll notice they offer male characters as examples. But before we had Tony Soprano, we had Carrie Bradshaw. It can be argued that the main female characters of Sex And The City were antiheroes in their own way — Carrie would alternately seem sympathetic but next minute she’d do something most of the audience wouldn’t identify with at all. This is an essential element of the fictional antihero.

More recently we have a complex, fascinating female antihero in Animal Kingdom’s Janine Cody (aka Smurf). The discussion around this character is often about what makes a ‘good mother’, a discussion I don’t remember James Gandolfini being asked to comment on. Society has higher expectations for mothers than for fathers, and this is reflected in stories.

I expect we will see more female antiheroes on screen. Because of that gendered expectation differential, it’s actually better sometimes to have a female antihero, if you really want the audience to pass judgement. Imagine how different the discussion would have been if Skyler White had been the main character of Breaking Bad.

I see this double standard pop up all the time in novels […] We forgive our heroes even when they’re drunken, aimless brutes or flawed noir figures who smoke too much and can’t hold down a steady relationship. In truth, we both sympathise with and celebrate these heroes; Conan is loved for his raw emotions, his gut instincts, his tendency to solve problems through sheer force of will. But the traits we love in many male heroes—their complexity, their confidence, their occasional bouts of selfish whim—become, in female heroes, marks of the dreaded “unlikable character.”

In Defence Of Unlikeable Women

More recently, in her book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, philosopher Kate Manne has coined the word ‘himpathy’ to explain the extra empathy we afford men as a patriarchal default. It is therefore more difficult to write empathetic male anti-heroes than empathetic female antiheroes. Anyone who successfully manages it should be applauded. Then again, if we as readers don’t ‘like’ or ’empathise’ with a female antihero, perhaps it’s not actually the fault of the writer? Perhaps we are himpaths.

So, what exactly makes someone an anti-heroine on film? A ‘catch-all’ definition is this: someone who does bad shit for good reasons. A woman who’s flawed, but in the most relatable and almost inspiring of ways (because aren’t we all?), and whose decisions and development unfold on screen independently of their male counterparts.

They’re the Thelmas and the Lousies, the Beatrix Kiddos. We’re now saying buh-bye to the Disney princesses from our youth, who were (and remain; sorry Emma Watson/Belle) almost impossibly virtuous, beautiful and small-waisted. The anti-heroine of today is messy, gritty and imperfect in a more ways than one, often navigating her life with a moral compass that could probably use a service.

We don’t love that Veronica from Heathers literally kills a whole bunch of people, but her reasons for doing so resonate with us (in any case, who DOESN’T love our girl Wynona, even when she’s a murderous high-schooler?). Gone Girl’s Amy Dunne is arguably batshit, but is there anyone who hasn’t thought of a real-life application for her ‘cool girl’ monologue at least once since hearing it for the first time?

‘Three Billboards’ Shows The Anti-Heroine Is Finally On The Rise, Junkee

See also: “Heathers” Blew Up the High-School Comedy, an archived New Yorker article

Further Reading On The Antihero

- Are You Sick Of TV Antiheroes from LA Times

- The Top 10 Fictional Antiheroes from Litreactor. It would seem most antiheroes are male, but this list includes some women.

- A great definition of antihero, and a list of examples, can be found at TV Tropes.

- The Likability Trap: We like to root for the antihero, but not for the antiheroine, from Bitch Media

- A Day In the Life of a Troubled Male Antihero from Toast

- Writing The Antihero (And Why So Many Authors Get It Wrong) from The Passive Voice

So much about a character is invisible, in fiction as in real life; but what lies beneath the surface will affect every aspect of your story. If you really take the time to figure out who you’re dealing with, much will become clear.

CLAIRE MESSUD

Chick TV: Antiheroines and Time Unbound 2021

Yael Levy examines the underexplored antiheroine of early twenty-first century television in Chick-TV: Antiheroines and Time Unbound (Syracuse UP, 2022). Levy advances antiheroines to the forefront of television criticism, revealing the varied and subtle ways in which they perform feminist resistance. Offering a retooling of gendered media analyses, Levy finds antiheroism not only in the morally questionable cop and tormented lawyer, but also in the housewife and nurse who inhabit more stereotypical feminine roles. By analyzing Girls, Desperate Housewives, Nurse Jackie, Being Mary Jane, Grey’s Anatomy, Six Feet Under, Sister Wives, and the Real Housewives franchise, Levy explores the narrative complexities of “chick TV” and the radical feminist potential of these shows.

New Books Network

CHARACTER NEED

There is probably a finite number of human needs, though so many you’ll never be short of material. Take a pyramid you’re probably familiar with, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (misappropriated from Native Americans). There are a few problems with this hierarchy, so it pays to look at it critically:

The modern integration of ideas from neuroscience, developmental biology, and evolutionary psychology suggests that Maslow had a few things wrong. For one thing, he never gave much thought to reproduction. He conceived of “higher needs” as completely personal strivings, unconnected from other people, and totally divorced from biological needs. Parental motivations were completely missing from his hierarchy, and he placed “sexual needs” down at the bottom—along with hunger and thirst. Presumably, sexual urges were biological annoyances that could be as well dispatched by masturbation as by having intercourse, before one moved back to higher pursuits like playing the guitar or writing poetry.

Psychology Today

CHARACTER PROBLEM

Every hero needs both an inner and outer problem. In developing fairy tales for Disney Feature Animation, we often find that writers can give the heroes a good outer problem: Can the princess manage to break an enchantment on her father who has been turned to stone? Can the hero get to the top of a glass mountain and win a princess’s hand in marriage? Can Gretel rescue Hansel from the Witch? But sometimes writers neglect to give the characters a compelling inner problem to solve as well…They need to learn something in the course of the story: how to get along with others, how to trust themselves, how to see beyond outward appearances. Audiences love to see characters learning, growing, and dealing with the inner and outer challenges of life.

Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey

In children’s stories where there is no psychological or moral shortcoming and won’t learn anything or change in any psychological way by the end of the narrative, your character will (probably) have a Problem. This problem is external to their psychology. Stories like this don’t tend to be as emotionally interesting, but are appropriate for, say, humour, which only needs a character to serve as the Every Child.

- In Stuck by Oliver Jeffers, the boy’s problem is that something is stuck in a tree and he can’t reach it down.

- Dogger by Shirley Hughes is about the problem of losing a favourite toy.

- Nickety Nackety Noo Noo Noo by Joy Cowley and Trace Moroney features a resourceful, heroic girl who is perfect in every way, but her big problem is that she’s been abducted by an ogre.

There’s another kind of story where the ‘main character’ is the reader. Where Is The Green Sheep? by Mem Fox and Judy Horacek is one example of this: The reader’s problem is that the book asks them to locate a green sheep, but that’s impossible until turning the final page. Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown is another example of a perennial favourite which doesn’t seem to follow any of the usual rules of story — again, this book addresses the young reader directly. The child is the character, saying goodnight to the items. This is more secular prayer than complete narrative.

Do all children’s book characters need a Problem, if they don’t have a moral or psychological shortcoming? Again the answer is not always, actually.

- The Biggest Sandwich Ever by Rita Golden Gelman and Mort Gerberg is a carnivalesque story in which a man turns up and makes an enormous sandwich. In a carnivalesque story, there doesn’t have to be a problem as such, because the unsupervised play itself is the story — equivalent to the big struggle scene in a more common type of story. A carnivalesque story is a ‘toy story’ — all about play and enjoyment with no ‘broccoli’. However, even in The Biggest Sandwich Ever, the characters do face a problem by the end: After stuffing themselves full of sandwich, they are now faced with the task of eating a giant pie.

- More! by Peter Schossow is a wordless picture book which celebrates the joy of walking (flying) along a beach on a windy day.

By the way, sometimes the initial problem exists only to get the story rolling. This is what Hitchcock called a McGuffin.