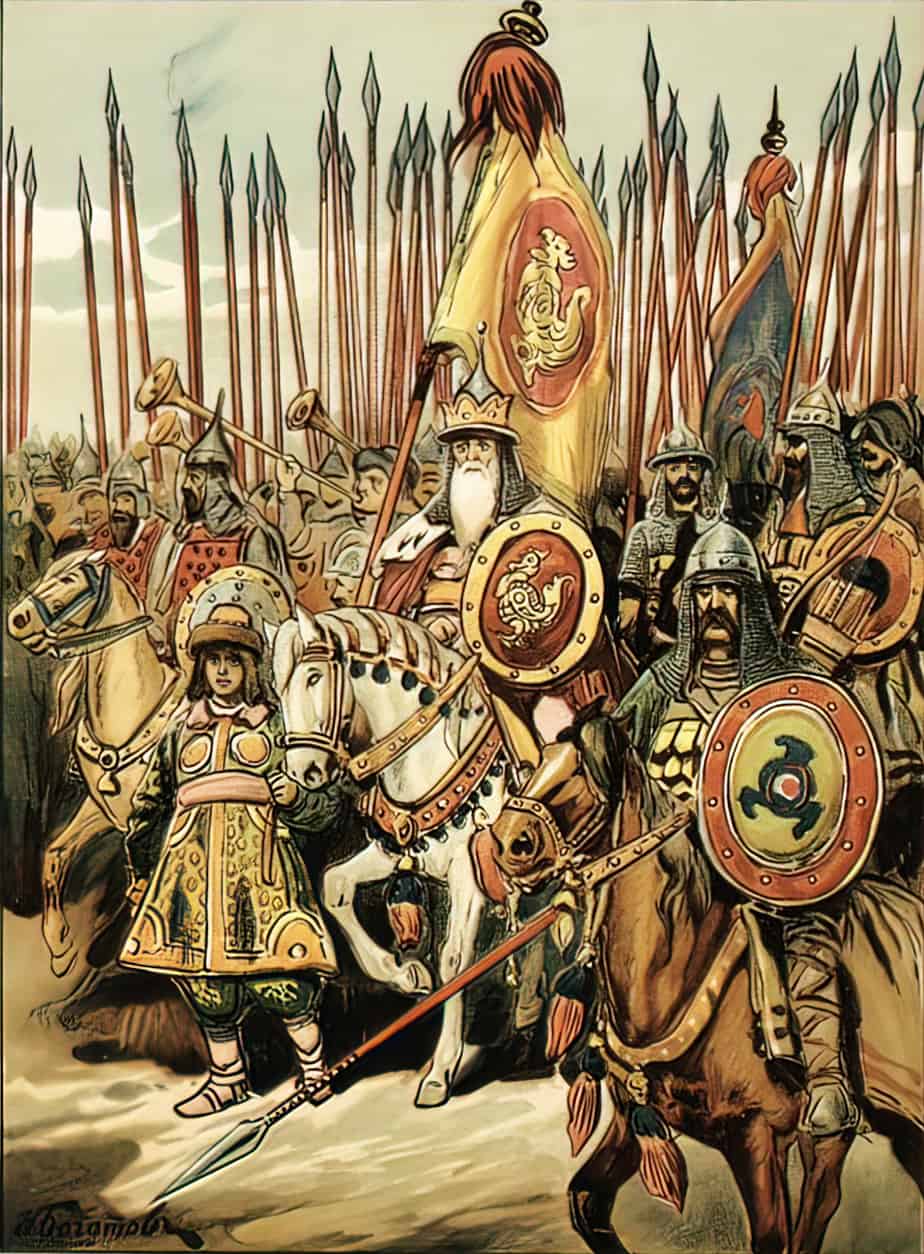

All complete narratives feature a big struggle scene. No, that doesn’t have to be a literal big struggle scene, Lord of the Rings style. In fact, we should be thinking outside that box altogether. One thing I love about Larry McMurtry’s anti-Western novels (especially Lonesome Dove) is that he condenses the gun big struggles and torture scenes in favour of character conflict.

Conquer without struggle and you will succeed without glory

Corneille

I often feel the battle sequence in a movie goes on too long. I feel this way about the children’s animation Monster House and also about the Pixar animation Inside Out. The former happened because the plot was too thin in general, the latter because a big struggle-free myth structure should more naturally be shorter.

WHAT IS THE BIG STRUGGLE SEQUENCE?

More commonly it’s known as the climax.

When your character reaches the climax, everything is stacked against them. They think fast, piecing together clues in their head. Usually, those clues are tidbits of knowledge you’ve placed earlier in the story, along with hints the main character observes in the moment. The protagonist assembles these clues into an important realisation. Then they use their newfound understanding to win the day.

Mythcreants

I’ve also seen it called The Dark Moment.

Here it’s called a Black Moment:

Do you have a black moment—a point near the end of the manuscript where your character has lost something or someone extremely important to him/her and all appears to be lost and failure seems inevitable? This usually happens right before he/she has a revelation or a breakthrough of some sort and throws him/herself back into the intensified conflict with a new determination, leading into the climax.

Naomi Edits

I’ve also heard it called ‘The Big Doom‘. Whatever you call it, this part of a story looks like this:

- The big struggle is the final conflict between main character and opponent and determines which of the two characters wins the goal.

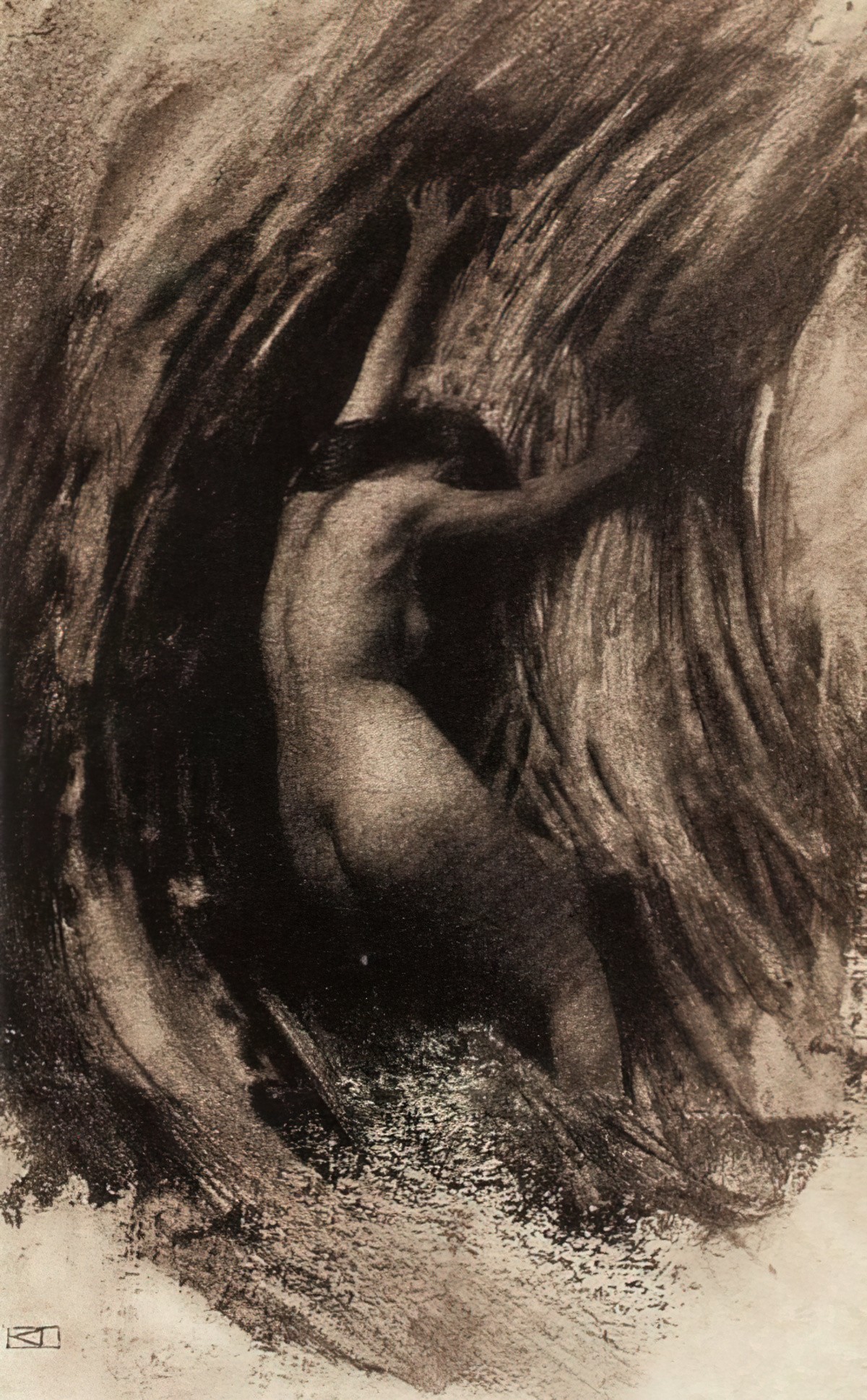

- Characters come close to death, spiritually or actually, depending on the genre.

- So, how to portray a big struggle… metaphorically? Sometimes this involves playing with spatial perceptions in some way. For example, in her re-visioning of Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter makes use of mise en abyme. Other techniques include playing with scale, making use of The Overview Effect, or otherwise inducing some kind of spatial horror.

- The big struggle sequence can also look like not much at all. As Captain Awkward says in a post about running into family after estrangement, “anticlimax — a good outcome on paper, since it means nothing escalated — can hit some of us as hard emotionally as anything we feared would happen.” A non-big struggle, when expected, is also a ‘big struggle scene’.

The big struggle sequence looks quite different in the battle-free myth form. Namely, the fight will be internal, externalised as a representation of the main character’s psychology. These stories avoid sturm und drang.

A movie is about an emotional struggle. The physical struggle is a manifestation of that.

John Gary

Torture your protagonist.

The writer is both a s*dist and a mas*chist. We create people we love, and then we torture them. The more we love them, and the more cleverly we torture them along the lines of their greatest vulnerability and fear, the better the story. Sometimes we try to protect them from getting booboos that are too big. Don’t. This is your protagonist, not your kid.

Janet Fitch

[One] reason an ending may fail to satisfy is that the author is trying to spare the characters some hurt, this time the anguish of confrontation. Remember, you cannot protect your characters—the words protagonist and antagonist have agony built in.

Schaum’s quick guide to writing great short stories by Margaret Lucke

You have to die a few times before you can really live.

Charles Bukowski

THE BIG STRUGGLE SEQUENCE IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

HELPERS

A child’s main shortcoming is that they are small and without power, so a lot of children’s stories have historically relied on an adult stepping in to help. The child’s main job was to find someone more powerful. Victorians preferred the version of “Little Red Riding Hood” in which the adult male woodcutter saves the day, and alternatives of that era have basically been forgotten.

The hero or heroine of a fairy tale usually cannot kill the dragon or marry the princess without help. This, of course, is contrary to the American tradition that if you go it alone and work hard enough, you will get to the top. In fairy tales, characters who refuse help, or refuse to help others, end up covered with tar or talking frogs and snakes.

Alison Lurie: Don’t Tell The Grown-up: The subversive power of children’s literature

Not all fairy tales follow this general rule, of course. That’s because the fairy tales which we read today have been edited by Victorian men who seemed to harbour their own fantasies of stepping in to save women and children. Fairy tales such as “The Gallant Tailor” and “Mollie Whuppie” feature protagonists who save themselves, but it’s unlikely you were exposed to those as a child.

In contemporary children’s fiction, children fight their own big struggles. However, they very often call in someone more powerful/older to help them in the pre-big struggle stage. That helper might be just a little bit older, or they might be eccentric (powerless in their own way).

- In Monster House the children call on the help of the guy who plays computer games down at the arcade.

- Harris Trinsky in Freaks and Geeks

Or the helper might be very old e.g. a grandparent, neighbour, wizard/witch or realistic equivalent.

These days help may come from the Internet. Courage the Cowardly Dog was one of the first children’s shows to do this — back when the Internet was very new and therefore novel. Courage would regularly consult the personified PC in the Bagge family attic. 25 years on, children’s writers seem less enthused about having The Web solve children’s problems. Now writers of realistic contemporary fiction might have to contrive ways to keep phones out of their characters’ hands all the time.

The people who regularly help children in real life rarely help them in stories. Therefore, you’ll rarely see a parent or a teacher helping a fictional child in any useful way. They may try to help, but inadvertently make the situation worse. This is to do with wish fulfilment — the wish to be independent. Or rather, the first step towards independence.

WHAT DOES A BIG STRUGGLE LOOK LIKE IN CHILDREN’S STORIES?

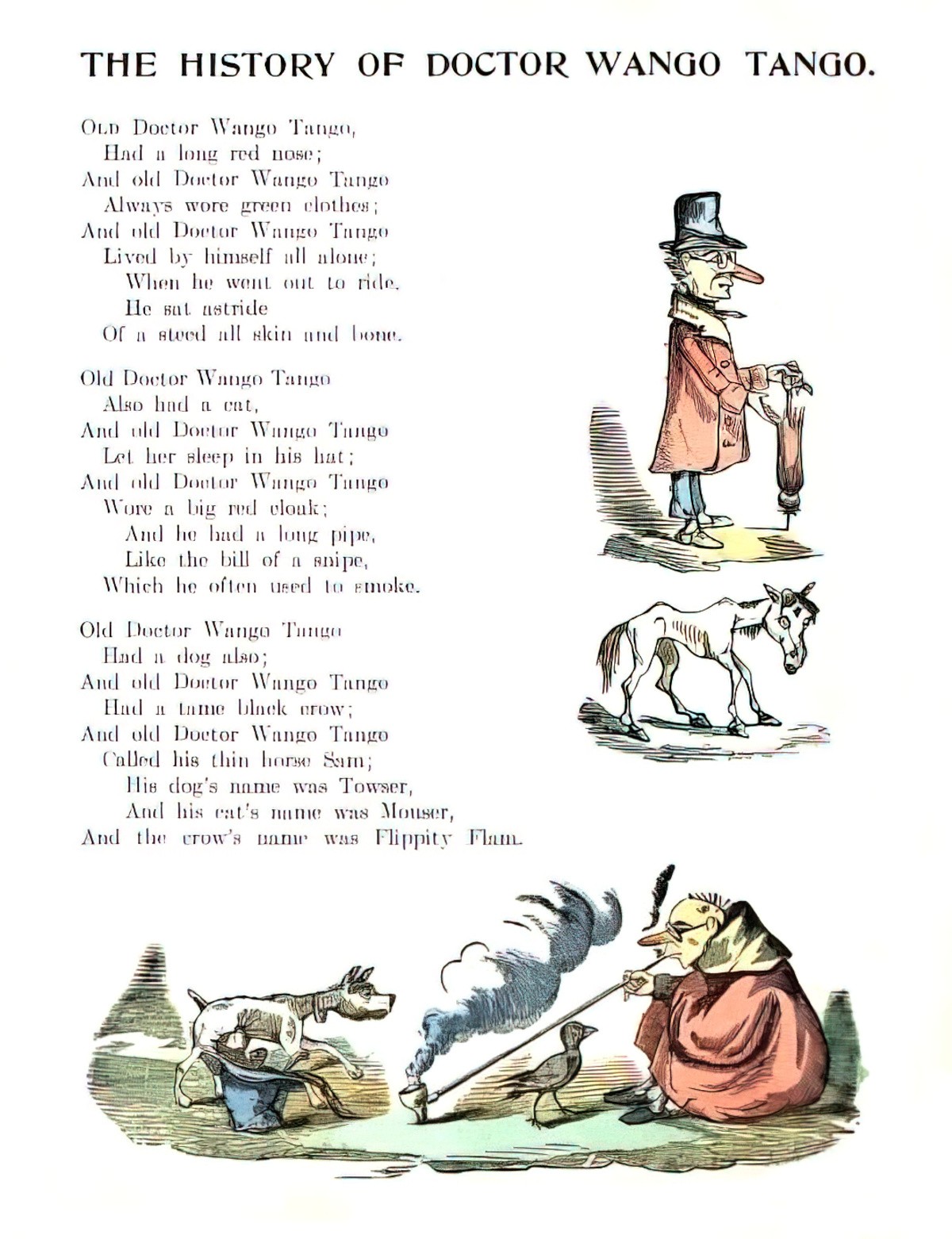

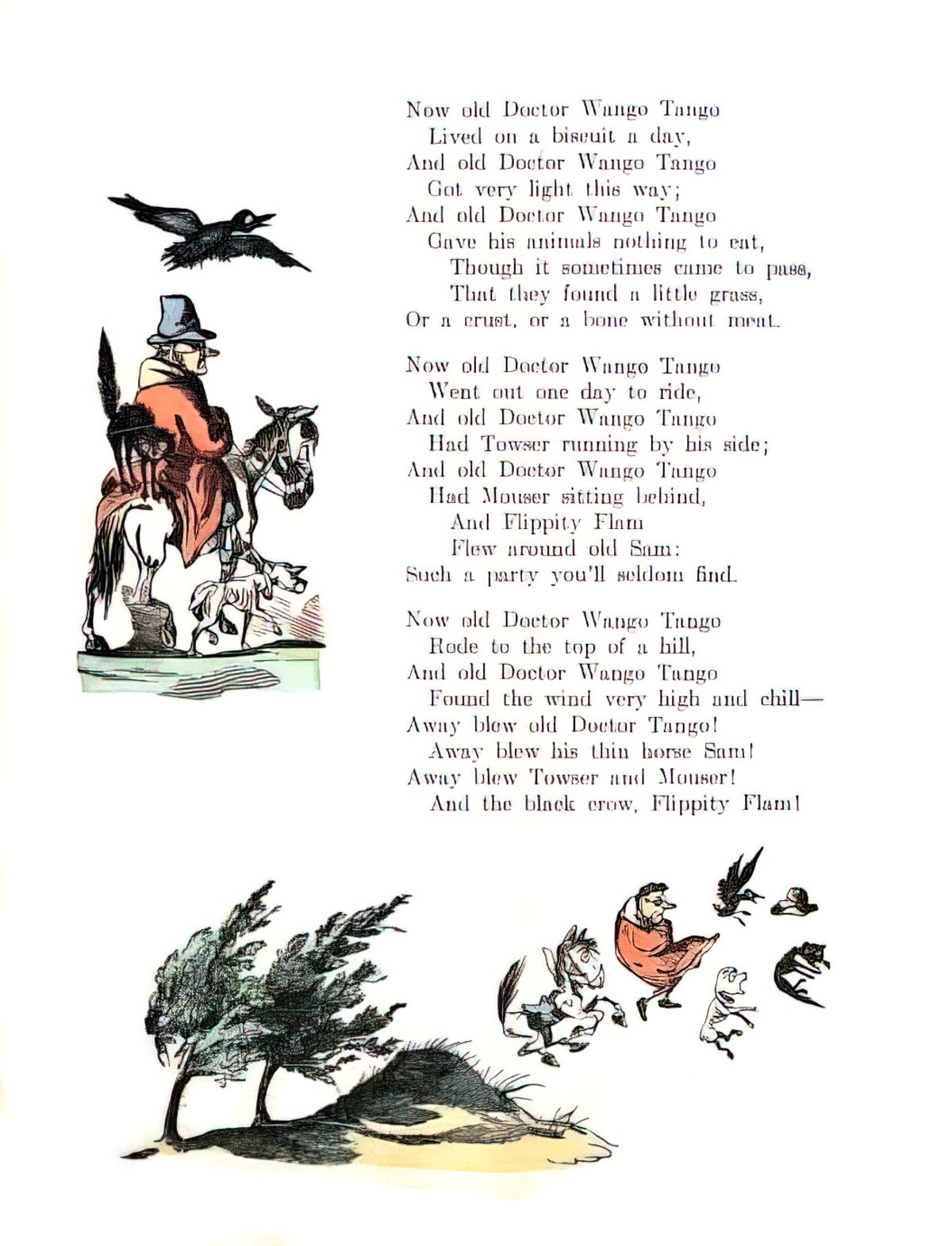

“The History of Doctor Wango Tango” from Slovenly Peter, or, Cheerful stories and funny pictures for good little folks illustrated by Hoffman Heinrich. The character is simply blown away by a convenient gust of wind.

In books for the very young, you’re not going to find many guns, bows and arrows, fisticuffs and arguments (though you will sometimes). Still, picture books definitely feature ‘big struggles’.

- Oftentimes, the big struggle phase seems to comprise about half the entire book.

- The big struggle scene may be a ‘culmination’ of ridiculousness (followed by calm after the page turn, perhaps with more white space and calming rhythm.)

- Therefore, the ‘big struggle scene’ in a picture book might also be called the ‘Culmination’.

- It might also be called ‘The Fright‘.

- The big struggle isn’t necessarily between the child and the main opponent. Rather, another opponent will often step in.

Picture book author Katrina Moore thinks of picture book structure like this:

- Set up

- Escalation

- Climax/Low Point

- Resolution

- Wink

Obviously, the climax/low point maps onto the big struggle. (I love the term ‘wink’. For me, the broad concepts of set up and escalation aren’t quite specific enough.)

What form does this so-called big struggle sequence take in picture books? I’ve been breaking down the story structure of picture books for some time now. Now it’s time to take a look at the picture books on my shelf and those studied on this blog.

I’ve seen the low point before the climax described as a ‘nadir’, which seems a good word for it:

In the end, the protagonist has to use what they’ve learned in order to overcome their most powerful obstacle of all. This is the climax, and it is often preceded by a nadir where all hope becomes lost.

Nathan Bransford

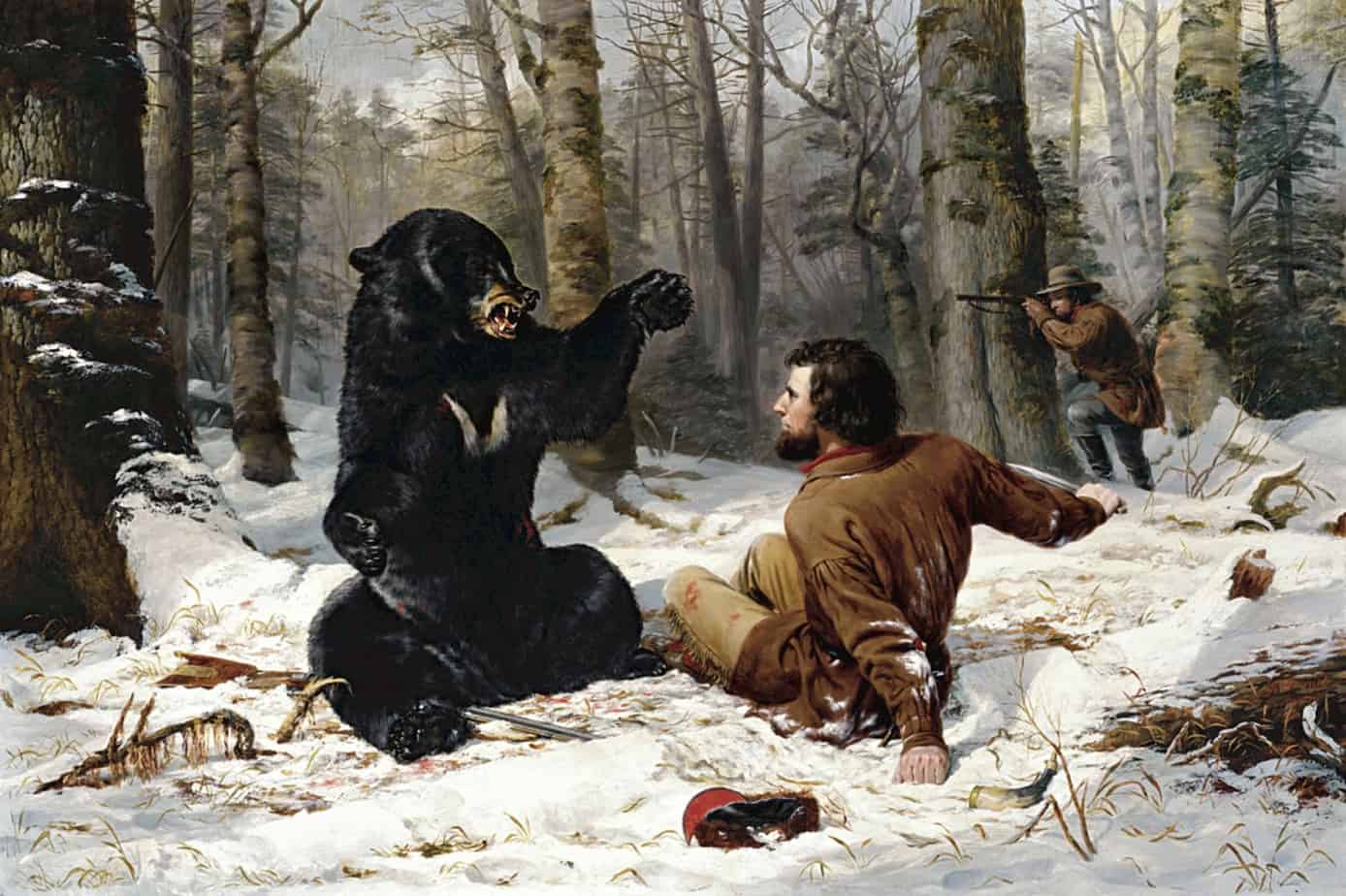

AN ACTUAL GUN BATTLE

Hunters with guns are switched out for the lesser opponents (the animals residing in Thidwick’s antlers) to create a more dramatic big struggle scene.

AN OVERSIZED BODILY FUNCTION

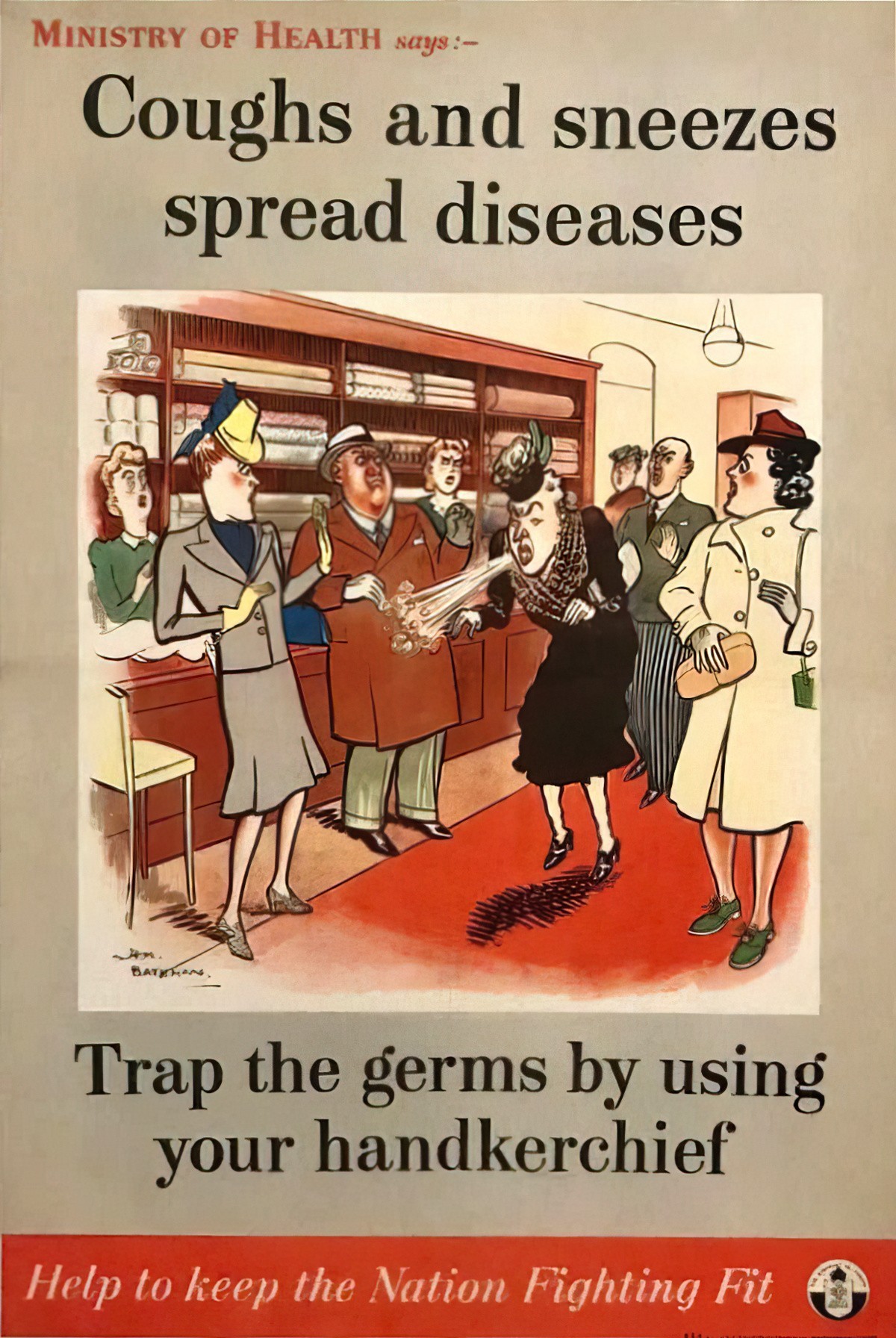

- You can see an oversized bodily function in The Three Little Pigs in which the wolf huffs and puffs and blows the houses down. However, in The Three Little Pigs, the sneezing is not the main big struggle scene. The main big struggle scene (at least in less bowdlerized versions) is the wolf falling splash into the pot.

- In Wake Up Do, Lydia Lou! by Julia Donaldson all the animals in the story sneeze together and wake up a sleeping toddler.

- In Yertle the Turtle by Dr Seuss, the king turtle is toppled off his perch when the turtle on the bottom of the stack burps.

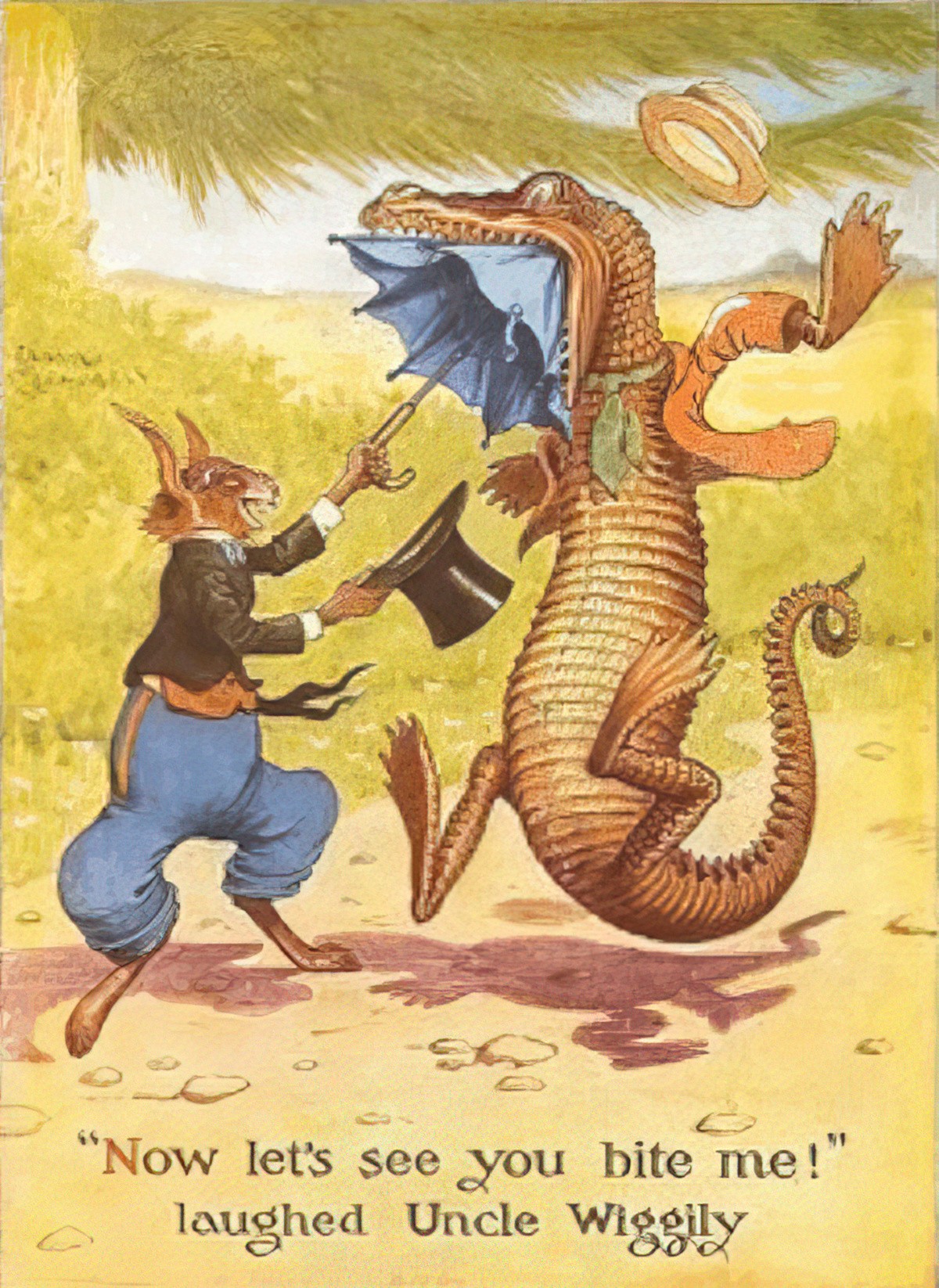

TRICKSTER HERO WINS BY SAPPING THE OPPONENT’S STRENGTH/POWER

- Our hero is a trickster archetype who challenges the opponent to perform things which will eventually lead to their own downfall. We see tricksters in classic tales such as The Emperor’s New Clothes.

- In a mythically structured narrative our protagonist defeats a dragon as an archetypal trickster, tiring him out until he’s fast asleep by challenging him to perform tiring feats. (The Paper Bag Princess by Robert Munsch)

A SCARY CHARACTER SUDDENLY POUNCES AFTER A LONG LEAD UP

This kind of story has its origins in oral narrative such as Little Red Riding Hood. The young listener/reader KNOWS what’s going to happen — the thrill is in the waiting.

- In Wolf Won’t Bite by Emily Gravett wolf has enough of performing circus tricks for three show-off little pigs and eventually bites them.

THE CULMINATION OF RIDICULOUS, ESCALATING (POSSIBLY NEAR DEATH) EXPERIENCES

This often happens in a tall tale or in a comic classic/carnivalesque plot.

- In The Five Chinese Brothers by Claire Huchet Bishop a city tries to murder a man but they can’t do it because he has four brothers and each has a secret superpower. Battle scenes: an attempted drowning, an attempted execution, an attempted burning at the stake, an attempted burning in the oven.

- In And To Think I Saw It On Mulberry Street, Inside a boy’s imagination, a simple horse and cart becomes an entire procession of motley scenarios. The illustration starts simple then becomes more and more detailed until nothing more will fit on the page. The big struggle scene, in other words, is extreme chaos.

- In Stuck by Oliver Jeffers there are so many things stuck in a tree that it’s impossible to imagine anything bigger or more ridiculous.

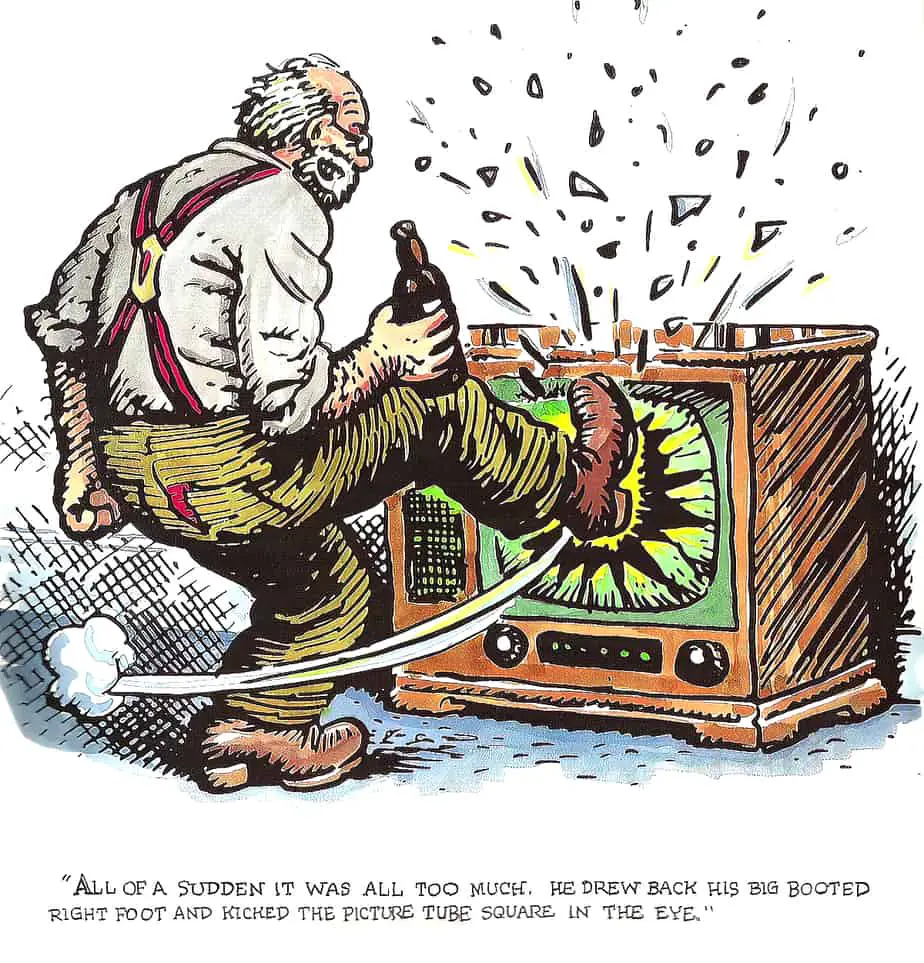

THE MAIN CHARACTER HAS A TANTRUM

Most common in comedy picture books. The childlike character isn’t getting what they want so they just lose it. These stories work if the main character’s shortcoming includes impatience and treating others badly. Young readers will identify well with this particular shortcoming, as their frontal cortexes aren’t fully developed — they know exactly what it feels like to not get what you want and to lose control as a result.

- The Tale of Two Bad Mice by Beatrix Potter is perhaps the ur-picturebook for all modern stories involving loveable, main character tantrums.

- Z is for Moose — Moose realises he’s not getting a part in the alphabet book, which is going to Mouse. He wreaks havoc on the illustrations in a very clever, meta kind of way.

- Pig The Winner — Pig the Pug cheats at games but when Trevor wins he chucks a wobbly and ends up injuring himself with the bin.

- Pigeon Wants A Puppy — When Pigeon doesn’t get his puppy he yells, “I want a puppy! Right here! Right now!”

THE OPPONENT IS INJURED/SCARED OFF BUT NOT KILLED

- In Garth Pig And The Ice Cream Lady by Mary Rayner a trickster wolf is pushed into the river. This doesn’t kill her — she dashes off into the wilderness.

- InThe Amazing Bone by William Steig a trickster fox is turned into a mouse by a magic bone

THE MAIN CHARACTER GETS CAUGHT UP IN THEIR OWN TERRIBLE PLAN

This kind of big struggle happens when the character is ‘their own worst enemy’.

- A brilliant example of this kind of inner big struggle occurs in This Moose Belongs To Me by Oliver Jeffers, in which a boy on a journey literally gets entangled in the yarn he draped about precisely to help him find his way home.

- In Neil Gaiman’s middle grade book Coraline, the big struggle sequence is a chapter straight out of a gothic novel, in which the main character must work her way out of her imaginary household before it morphs into such a shape that it will somehow enfold her within its clutches.

THE MAIN CHARACTER SHOWS KINDNESS AND WINS THE ENEMY OVER

During the climax of the story, your hero shows an astounding level of kindness to the enemy. It might come in the form of unconditional acceptance, unusual empathy and understanding, or an actual gift with a great deal of personal significance. The hero might even give away the very thing the villain was trying to steal. This gesture of goodwill causes a change of heart. The villain decides to stop doing harm, at least for now. In The Lego Movie, all the Lego realms are terrorized by Lord Business. He plans to glue all the Lego pieces permanently into place, freezing everyone exactly how he wants them. The main character, Emmet, is supposed to be a special person with the power to stop Lord Business, but toward the end, he discovers that he’s no more special than the next Lego. To stop the fighting and gluing, Emmet meets with Lord Business. Emmet explains that Lord Business is also special, and that he has something unique to contribute to the world. Because of this conversation, Lord Business abandons his evil plans. The gesture of goodwill is a good match for a character-focused story. But like other character-based conflicts, it’s important to set things up ahead. You’ll want a sympathetic villain with a motivation the audience understands. However, you don’t have to tell their whole backstory in a flashback. Your hero can piece together the villain’s backstory and motivation, and then use that information in making their gesture.

Mythcreants

A COMPETITION, PROBABLY RIDICULOUS

THE FOUR-PART CLIMAX

If you think in terms of ‘climax’ rather than ‘big struggle’ followed by ‘anagnorisis’ and ‘new situation’ you may prefer to break climax into further parts:

The climax of a novel actually has four components:

- The run-up to the climactic moment (last-minute manoeuvring to put the pieces in their final positions)

- The main character’s moment of truth (the inner journey point toward which the whole story has been moving)

- The climactic moment itself (in which the hero directly affects the outcome)

- The immediate results of the climactic moment (the villain might be vanquished, but the roof is still collapsing).

— Writer’s Digest

Moment of truth = anagnorisis

Climatic moment itself = near-death big struggle moment

Matt Bird of Cockeyed Caravan breaks down the Battle stages according to which part of the main character is being challenged. I have noticed he’s on the money for the vast majority of stories:

In the best stories, no matter what the genre, the hero is first challenged socially (often in the form of a humiliation at the beginning), then challenged physically (often in the form of a midpoint disaster), then challenged spiritually, as the hero is forced to either change or accept who he or she really is (often around the ¾ mark).

The pilot of Breaking Bad is exactly like this, starting with Walt’s humiliation as a lowly car washer serving his own students, followed by the diagnosis of lung cancer, then the moral dilemma — does he follow that idea to become a drug lord or doesn’t he?

THE CHARACTER MAY NOT REALISE THE STRUGGLE IS OVER

And once the storm is over, you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive. You won’t even be sure, whether the storm is really over. But one thing is certain. When you come out of the storm, you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what this storm’s all about.

Haruki Murakami

OTHER LINKS

For pantsers who haven’t decided on the big struggle beforehand, here’s some tips on how to come up with one.

RELATED TERMS

THREEFOLD DEATH: According to Dan Wiley’s entry in Duffy’s Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia, threefold death is a motif of the early Irish aideda in which a victim is killed by three different means in rapid succession, often wounding, drowning, and burning. Examples of this motif can also be found in literature of folklore of Wales, France, and Estonia. The widespread nature of the motif makes some scholars think it began in a hypothetical Indo-European tri-functional sacrifice in which human victims were offered to a triad of divinities. Two of the best examples are found in Aided Diarnmata meic Cerbaill (The Death of Diarmait mac Cerbaill) and Aided Muirchertaig meic Erca (The Death of Muirchertach mac Erca). The tales are typically set in the early Christian period between 500 and 699 CE. The narrative pattern typically is (a) a crime is committed against the church, (b) it is prophesied the offender will die a threefold death, (c) such a death does occur. See Duffy 10-11.

Literary Terms and Definitions

Header painting: Harry Brooker – The Tug of War