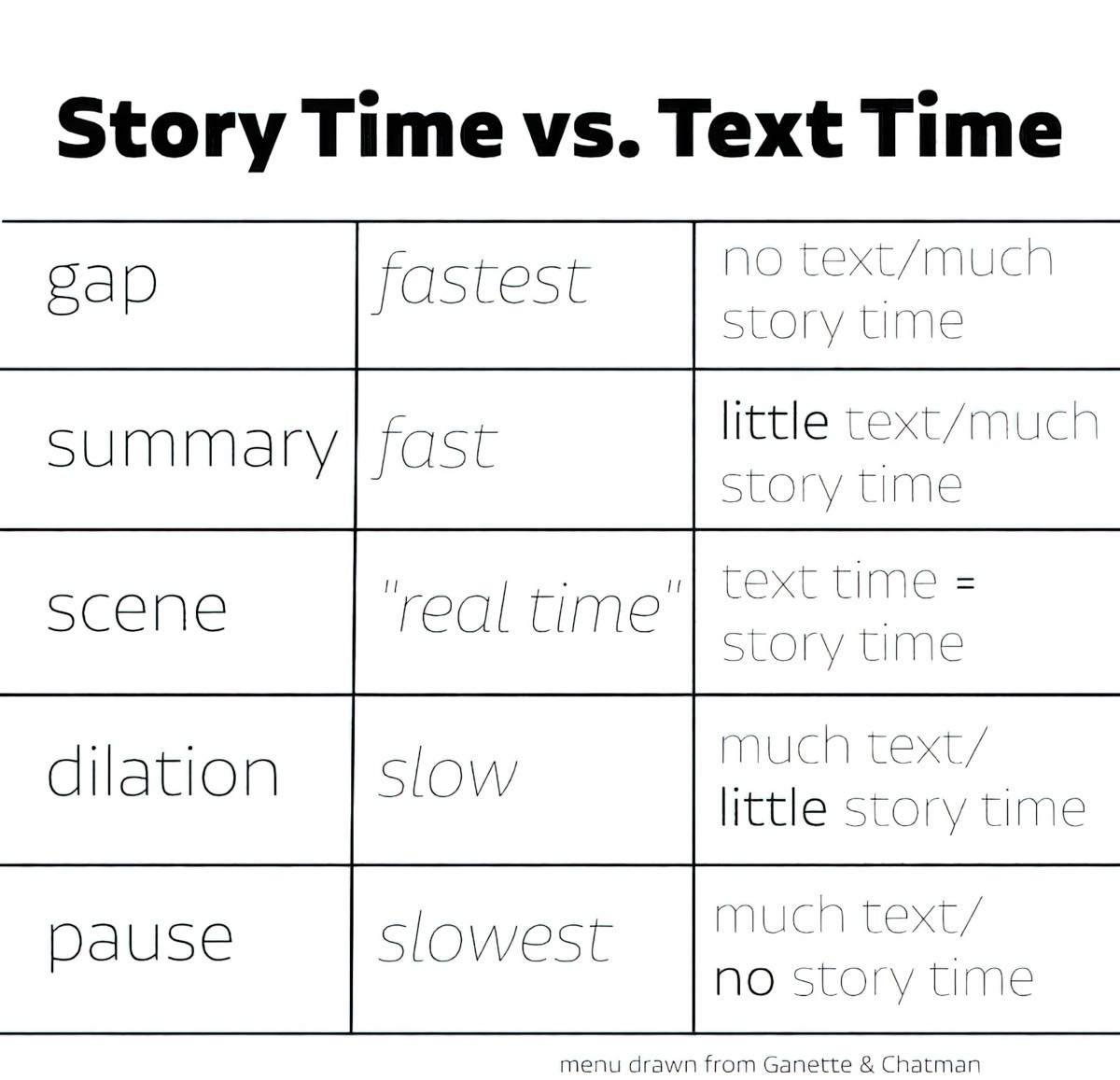

Narratologists have come up with a variety of ways of talking about the pacing of a story. I recently tried reading Gerard Genette and it gave me brain ache. I thought, this is fascinating but I can’t absorb all this. I’ll come back to it. Yet it’s important to have vocabulary which allows us to talk about pacing. Pacing is important:

All stories split into two kinds of time. We might call them:

- How Long The Story Takes An Audience To Get Through: This describes how long it takes to experience the story, by either reading it, listening to it or watching it. If a story plays out on screen, the creators have full control over how long it takes (barring audiences pausing for toilet breaks). If a story is read, the reader has far more control over how long it takes to get through a story.

- How Long The Author Meant The Story To Last In The Imagined Story World: this kind of time is a fictional construct.

Some stories are big on narrative summary, which means you can have a short story which spans three generations in Imagined Time.

Then you get stories which expand a single afternoon into the length of a book. (Mrs Dalloway.) Ulysses is a standout example: 933 pages to describe a single day. (Interestingly, every chapter covers an hour of imagined time.)

Some stories work mostly with dialogue, which results in a story whose Imagined Story Time pretty much maps onto how long it takes to read. There’s a word for these kinds of stories: Isochronic(al) (see below for a definition and examples of that). Gerard Genette came up with the word but at the same time, recognises it’s actually impossible to create a story where the performance/reading time perfectly aligns with it.

All that we can affirm of such a narrative (or dramatic) section is that it reports everything that was said, either really or fictively, without adding anything to it; but it does not restore the speed with which those words were pronounced or the possible dead spaces in the conversation… Thus a scene with dialogue has only a kind of conventional equality between narrative time and story time… but it cannot serve us as reference point for a rigorous comparison of real durations.

Gerard Genette, Narrative Discourse

Writers can only approximate the feeling of isochrony.

Pace is crucial. Fine writing isn’t enough. Writing students can be great at producing a single page of well-crafted prose; what they sometimes lack is the ability to take the reader on a journey, with all the changes of terrain, speed and mood that a long journey involves. Again, I find that looking at films can help. Most novels will want to move close, linger, move back, move on, in pretty cinematic ways.

Sarah Waters

But this week I’m reading a new book called Meander, Spiral Explode by Jane Alison, about patterns in story. I’m delighted to find that Alison has included, alongside her structural patterns, an analysis of pacing patterns.

At first Pause and Gap sound like the same thing, but they’re opposites.

GAP

Where there is Gap there is no text — ‘the text goes mute’ — and we can leap over many years of story time. Eons, even. In film there might be a very slow fade, a change of hue, differently paced music. We know that a great stretch of time has just passed.

The narratee may find, after a Gap, that they need to fill in what has just happened. The reader must extrapolate. If the storyteller has done their job, the audience has been given enough information to do so.

An example I came across recently was the time jump in “Queenie“, a short story by Alice Munro. Munro is well-known for her ability to perform magic tricks with time, so of course she has the Gap in her toolbox. (The Gap is where the asterisk is below.)

As I had thought of myself being kind to Mr Vorguilla, or at least protecting him, so unexpectedly, a little while before.

*

I was at Teachers’ College when Queenie ran away again. I got the news in a letter from my father. He said that he did not know just how or when it happened.

“Queenie”

There are certain parts of story which should be Gaps, when our writerly instinct might be Summary. One of those is ‘Getting From One Place To The Other’. Modern readers are well-versed in extrapolating the content of Gaps, and you can safely pull your characters out of one scene and plonk them in another. The reader will understand that there has been some travel in there somewhere. (Within reason.)

Others use the word ‘ellipsis’, which also refers to blank spaces within a narrative while the flow of events keep unfolding.

SUMMARY

I’ve encountered the term ‘narrative summary’. Same thing. Within the storyworld, something takes a long time to happen, when compared with how quick it is to read.

As beginning writers we tend to be afraid of Summary, thinking every event in a story has to be a scene, alive with the five senses, showcasing beautiful language. But knowing when to write scene vs. when to summarise is vital. Self-Editing for Fiction Writers, Second Edition by Renni Browne and Dave King talks about this.

Summarising is an especially vital skill for the short story writer. Alison points out that summary can be boring, but one trick is to splice up summary with well-chosen detail. Annie Proulx, who likes to write across three generations of family in a single short story, is a master of this technique.

One kind of writing style juxaposes narrative summary against lengthy passages which delve into the details of a relationship or an interaction, exploring the messages and the metamessages, analysing interiority.

In her book Detransition, Baby, author Torrey Peters does just this, then follows it up with an extremely satisfying paragraph of narrative summary about a different event. In a single paragraph, she tells the reader a short story in its own right:

A girl he knew who worked for the promoters told him which bar Xtina and her entourage were heading to after the show, and there he met one of her dancers — a tall American named Tiff who spoke with a Texan accent that Sebastian found both intoxicating and difficult to understand. Tiff seemed weary with tour life and wanted to see the city. To impress her, Sebastian and a friend offered to build her a bonfire in a nearby snow-filled industrial park along the docks, so that she could both stay warm and see the sea. To impress her further, they got another friend to bring cocaine. When the police arrived, unsurprisingly drawn to a two-meter bonfire in the empty lots along the water, they’d all been detained — but the officers seemed not to want the hassle of it all and so they were let go. The next day, and not coincidentally, everyone on Sebastian’s swim team was subjected to a drug test. His came up positive for both marijuana and cocaine.

Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

When a writer creates a summary and splices it up with minute detail, another thing happens — the writer has now created an Overview Effect for the reader, whereby the reader sees the large and the tiny both at once, and feels a kind of literary vertigo.

A narrative must have two kinds of time: first, its own, like music, actual time, conditioning its presentation and course; and second, the time of its content, which is relative.

Thomas Mann (The Magic Mountain, 1924)

SCENE

Around the middle of this continuum, the time it takes to read words on the page pretty much equals the time it takes to play out in the world of your story.

The word ‘scene’ comes from drama, where the pacing is driven, and rather limited, by how fast events can be performed before us by actors on a stage.

When it comes to the written forms of story, Jane Alison offers the transcription of a character’s diary entry as the purest example of ‘real time’, in which there is an exact match between the pacing of the story and the speed at which the narratee experiences the story. (When we read a letter in a novel, and when the character reads this letter in a novel, time matches up. Unless the character is a much faster or much slower reader, of course.)

Still, let’s plonk ‘epistolary material’ right in the middle of our imaginary continuum.

There are parts of a story which we really must turn into scenes, or risk leaving the reader feeling cheated. It’s a natural instinct for writers to want to protect our precious characters in the first draft, but readers really do need to see them come close to death.

That’s rarely pleasant, but if we turn these Battles into Gaps, perhaps because we’ve made the executive decision that there’s too much horribleness in the world already, we’d better line something else up as the Proxy Battle. Alice Munro makes for a good case study in this technique.

DILATION

Dilation refers to the action or condition of becoming or being made wider, larger, or more open.

This is where a reader is forced to slow down. Generally, when a story dilates, the author has done this to make room for description.

If the printed words showing a story event take more time to read than the event would: dilation.

Meander, Spiral, Explode

Imagine an app which allows you to watch YouTube videos at a fraction of the pace. I sometimes watch tennis videos like this. This is dilation. […] Text time is greater than story time.

Jane Alison offers an example involving a man being shot by a bullet. The time it would take within the story for the man to be hit by the bullet is a microsecond. But the description of the thoughts that go through his mind take far longer for us to read than it would take for the character to die.

There’s a risk of dilating in the wrong place. Know what you’re going for on any given page — do you want the reader turning pages quickly? The following advice is from an article about writing page-turners, so bear that in mind, but Jordan Rosenfeld lists 8 Mundane Elements You Should Cut From Your Story. ‘Thoughts in the midst of an action’ is one of the eight elements:

The moment when characters are in the midst of big, dramatic action is precisely the worst time to slow down the energy and momentum of a scene to insert thoughts, especially long, drawn-out thoughts or epiphanies. Yet I see it all the time in my clients’ manuscripts.

Let me give you an example of the difference in what I mean.

With too much thought:

The hillside shook violently beneath him and began to crumble. Julia screamed and reached out to him. A huge crack appeared just feet from him. If he tried to run toward Julia, the earth would swallow him up. This reminded him of one of the times he went volcano hunting with his father as a child. When the ground trembled, his father had simply scooped him up and dashed toward safety. Julia screamed again and he lunged across the crack like a fool.

Revised, with a brief observation:

The hillside shook violently beneath him and began to crumble. Julia screamed and reached out to him. A huge crack appeared just feet from him. If he tried to run toward Julia, the earth would swallow him up. He was a child again, but without his father to rescue him. Julia screamed again and he lunged across the crack like a fool.

Hopefully you’ll have done the work of letting the reader know about your character’s past studying volcanoes with his father long before this moment, making it unnecessary to fill in backstory in a moment of action where tension needs to remain high.

from Jane Friedman’s blog

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf is an excellent example of novel-length dilation. Nothing much happens if we describe the action: A middle-aged woman goes out in the morning to buy flowers for her party. She is visited by a former beau, then the party happens. The Prime Minster shows up. Unlike the man who died by his own hand earlier that day, Mrs Dalloway realises she doesn’t have the courage.

If this were the story it wouldn’t be much. But while she’s doing this, Woolf’s stream of consciousness narration takes us far beyond the trip to the florist’s, far exceeding Clarissa Dalloway’s movements in space.

I’ve also heard the term ‘narrative statis’ to describe dilation ie. when the narrative discourse continues while historical time is at a standstill.

PAUSE

The best description of a reality does not need to mimic its velocity. Whole books, whole research departments, are dedicated to the first half minute in the history of the universe.

Ian MacEwan, Enduring Love

When I first read about these terms, I thought each end of this continuum must be hypothetical. But no, writers do literally include the Pause in their work. It’s easy to imagine a Pause on film — it would be a freeze frame, like at the end of Thelma & Louise, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, 400 Blows, Evil etc.

Filmmakers use the term ‘freeze frame’.

Japanese film-maker Yasujiro Ozu is well-known for his take on the freeze frame, which is not frozen but simply a camera focusing on one specific shot for an extended period.

Other Japanese film-makers have emulated this, including Hayao Miyazaki in his animated films. There’s an entire category of Internet GIFs (often called cinemagraphs) which are basically pillow shots. (I collect the ones and pin them on Pinterest.)

But how does a writer make use of the Pause in a written story? A few blank pages? Well, perhaps. That would be experimental (and also a waste of paper).

Jane Alison offers an example of a Pause on the page: Those times when the reader is told what is not happening rather than what is happening (after the character gets shot with the ‘dilated’ bullet).

Highlighting what’s not happening is one way of freeze framing something in a written story. The reader waits with suspense to find out what IS happening, all the while on Pause.

Perhaps this is a subcategory of Sideshadowing, in which the narrator offers an alternative to the real world story, by imagining/dreaming/hallucinating how things might have been different. Unlike a flash back or a flash forward, sideshadowing can function to emphasise the present moment. This is why I consider sideshadowing a Pause. All the while, the reader is kept dangling, waiting to see what will happen in the ‘real’ world of the story.

How else might a writer achieve the Pause? By describing a photograph is another way. Technically, this is known as ekphrasis.

Ekphrasis was an old Greek pastime, and formed a genre in its own right.

The goal of this literary form is to make the reader envision the thing described as if it were physically present. In many cases, however, the subject never actually existed, making the ekphrastic description a demonstration of both the creative imagination and the skill of the writer.

Homer’s description of Achilles’ shield in Book 18 of the Iliad stands at the beginning of the ekphrastic tradition.

You might think modern readers have no time for it. Perhaps in genre fiction and children’s literature, that’s true. But literary writers sometimes make use of it. Alice Munro is a case in point:

He put his hand in a back pocket. “Here. Want to see a picture? Here.”

It was a photograph of three people, taken in a living room with closed floral curtains as a backdrop. An old man—not really old, maybe in his sixties—and a woman of about the same age were sitting on a couch. A very large younger woman was sitting in a wheelchair drawn up close to one end of the couch and a little in front of it. The old man was heavy and gray-haired, with eyes narrowed and mouth slightly open, as if he were asthmatic, but he was smiling as well as he could. The old woman was much smaller, with dyed brown hair and lipstick. She was wearing what used to be called a peasant blouse, with little red bows at the wrists and neck. She smiled determinedly, even a bit frantically, her lips stretched over perhaps bad teeth.

But it was the younger woman who monopolized the picture. Distinct and monstrous in a bright muumuu, her dark hair done up in a row of little curls along her forehead, cheeks sloping into her neck. And, in spite of all that bulge of flesh, an expression of some satisfaction and cunning.

Alice Munro, “Free Radicals”

Here’s another example from the opening of Seven Empty Houses by Samanta Schweblin (2015). A mother and (reluctantly accompanying daughter) are out looking at houses, for some reason:

We keep moving. My mother drives straight, without stopping in front of any of the mansions. She doesn’t comment on the huge windows or fancy doors, the hammocks or awnings. She doesn’t sigh or hum any song. She doesn’t jot down addresses. Doesn’t look at me. A few blocks down, the houses grow more spaced out and the grassy lawns flatten: carefully trimmed by gardeners and with no sidewalks in the way, they start right there at the dirt road and spread over the perfectly leveled terrain, like a mirror of green water flush with the earth.

Seven Empty Houses by Samanta Schweblin

Jane Alison offers the example from The Lover by Duras:

She goes on to a new block describing a photo of herself with her mother and brothers, a picture capturing her mother’s despair. These portraits aren’t decorative: like the missing image, they’re potent. Studying them, she find secrets, deep character traits revealed in eyes or mouth. Later she creates a long sequence of verbal portraits of women (I call it the “Catalogue of Women”). They portray, out of the blue, two expatriate women in Paris the narrator came to know decades later, as well as girls and women in Indochina, M’s friend Helene Lagonelle; the madwoman of Vinh Long; a beggar woman; and the “Lady of Savanna Khet,” whose scandalous affair ended in her lover’s suicide. These portraits seem detached from the drama: Duras lets them float in white space like postcards.

Why all this seemingly tangential material in a narrative about M and her lover? Why so much about photographs? And why does Duras keep switching between first person and third? […]

M turns herself to an object most often when speaking of herself as a writer. And she uses language that not only objectifies but makes legendary the girl and her world: they are the girl, the mother, the lover, “the famous pair of gold lame high heels.” This makes them singular worth regard. […] We’re with her looking at a picture, and she chooses what and how we see.

Jane Alison, Meander, Spiral, Explode, pp 128-9

An excellent example from children’s books is a scene from Mercy Watson Fights Crime. A burglar breaks into Mercy’s house but Mercy is too oblivious to know this. Instead, all she notices is what’s NOT happening. She was hoping for buttered toast, but sees no toaster (it has been stolen), no bread and no butter. She fails to notice the burglar and falls asleep immediately. In this case, the Pause is part of the set-up and punch.

Aside from literary fiction, popular songs can slow the pace of narrative right down to a pause. An example would be “The Box”, by Fad Gadget.

The camera pans across the room

And finally comes to rest upon an old picture frame

The photo shows a man in hat

A dog at heel

The man is fat

The dog is the same

Let me out…

Let me out…

Let me out…

I can’t stand the dark anymore

A POV of man in carbon monoxide fumes are choking him

His face turns pink

And now we see him winding down

The window streaked excretion brown

We watch him sink

Let me out…

Let me out…

Let me out…

I can’t stand the dark anymore

The shot a wide angle now

A man is banging on the door

Of a chrome elevator

Lights go out no air inside

Get no lift from this lost ride

On a cracked generator

Let me out…

Let me out…

Let me out…

I can’t stand the dark anymore

Now focus out

The lift goes down

Night creeps in

The screws go round

Blood runs cold

And now we stare up from our hole

Theme tune in, the credits roll

The story told

Let us out…

Let us out…

Let us out…

Someone gotta let me out!

ISOCHRONICAL STORIES

A story is isochronical if the timespan of the story and the time it takes to read the story (the ‘discourse timespan’) are the same. (Iso is a prefix meaning “equal,” used in fields such as meteorology.)

“Afternoon In Linen” by Shirley Jackson feels like a roughly isochronical short story.

The noun is ‘isochrony’.

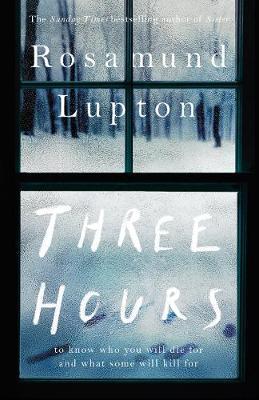

Three hours is 180 minutes or 10,800 seconds.

It is a morning’s lessons, a dress rehearsal of Macbeth, a snowy trek through the woods.

It is an eternity waiting for news. Or a countdown to something terrible.

It is 180 minutes to discover who you will die for and what men will kill for.

In rural Somerset in the middle of a blizzard, the unthinkable happens: a school is under siege. Told from the point of view of the people at the heart of it, from the wounded headmaster in the library, unable to help his trapped pupils and staff, to teenage Hannah in love for the first time, to the parents gathering desperate for news, to the 16 year old Syrian refugee trying to rescue his little brother, to the police psychologist who must identify the gunmen, to the students taking refuge in the school theatre, all experience the most intense hours of their lives, where evil and terror are met by courage, love and redemption.

Isochrony is more reliably achieved on screen because with words on a page, there’s no individuals vary in their reading pace.

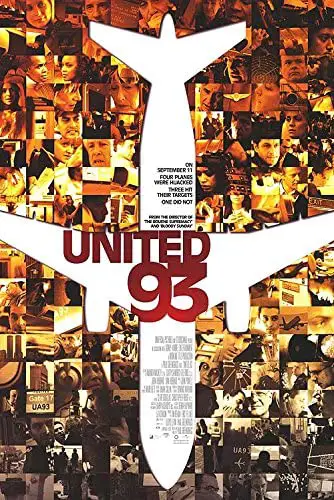

A real-time account of the events on United Flight 93, one of the planes hijacked on September 11th, 2001 that crashed near Shanksville, Pennsylvania when passengers foiled the terrorist plot. For more isochronical stories, search the tag real-time at IMDb.

- 24

- 1917

- 12 Angry Men

- Clue

- Locke

- The Guilty

- Compliance

- Carnage

- 24: Live Another Day

- Free Fire

- Exam

- Victoria

- Rope

- Phone Booth

- Unfriended

- Money Monster

- Snake Eyes

- Eye In The Sky

- 88 Minutes

PACING PITFALLS WHEN WRITING

Sometimes, when opening a story, storytellers aim for a suspenseful tone by slowing the pacing right down to almost nothing:

She tip-toed through the dining room and reached for the doorhandle. She placed her hand on the doorhandle, and turned it so it would not make a sound…

As an opening sequence this won’t work for most readers, because until readers get to know the characters, slowing down the pace — on its own — will not create suspense. The problem is, readers don’t care. ‘Don’t care’ is code for, ‘haven’t empathised with the characters yet’, so the story means nothing.

STRIKING THE BALANCE BETWEEN FAST PACED AND EMOTIONALLY SATISFYING

Haydu goes on to say this:

I do often see something in a manuscript that I find infuriating or fascinating or scary but the main character is sort of brushing by. Or very little time is spent exploring a fight that if I had it irl I’d obsess about for years.

I had the same reaction to a many scenes in Pretty Little Liars. To take one example, in season two Hannah and Emily tell Aria that her crush has been taking creepy photos of her while she’s asleep.

Aria says that she’s horrified, but then walks away from the table before asking more questions ie What, exactly, are the pictures of? She’s still basically fine.

It turns out later in that same episode that it’s probably not the crush who has taken the pics — it was Alison, the night she died. This explains from a writing perspective why the writers didn’t spend much time on Aria’s emotional reaction. The writers would have known the full story, and therefore sort of forgot what it must be like to not be in possession of the full story ie. To be Aria.

The sheer number of events that happen in PLL means that the writers don’t have (or take) the time to explore any one thing. The characters gloss past some potentially interesting emotional reactions, because it’s kind of like the Trump news cycle — one damn thing after another.

A STORY’S TIME SIGNATURE

Narratologists could never agree on which words to use to describe for which common concepts. They’ve ended up with a complete mess of overlapping terminology.

Fandom has its own, separate terminology. One term I like is time signature, borrowed from music.

Time signature: a notational convention used in Western musical notation to specify how many beats (pulses) are contained in each measure (bar).

In a video on tropes by Overly Sarcastic Productions, Red points out that the beginning of a story sets the reader’s expectation for the pacing that is to come. If a story starts slow, the reader will expect this pacing to endure. Start with fast-paced action, the reader will expect this pacing to continue (or, more probably, to spike).

Red also points out that if a story starts slow, the audience will expect this slowness to precede something exciting.

PACING AND GENRE

Different genres have different pacing. Genre helps readers find the pacing that is right for them.

Fast paced: Young adult dystopia, action

Slow paced: Noir crime, older stories in general

Any subgenre of crime can feel slow paced when authors utilise false leads and red-herrings, prioritising those over reveals. The number of reveals will also affect a reader’s experience of pacing. We don’t notice slower scenes when we are waiting with bated breath for a promised reveal.

THE MEANING OF SLOW BURN

Sometimes you’ll hear the word ‘slow burn’ applied to stories, especially in the romance genres. In a slow burn romance, sexual tension drives the plot towards the inevitable ending: Two characters find romance with each other.

At Book Riot, Nikki DeMarco describes the elements necessary for a slow burn to excite rather than frustrate:

- Deep character development

- A believable reason why the two characters can’t just get it on right away (a more difficult hurdle for contemporary writers, since most modern readers are socially encouraged to have sex — and a wide range of it — before marriage)

- Sexual tension (the author calls this unresolved tension though she seems to be describing sexual tension specifically)

Matt Bird, who wrote Secrets of Story might add another crucial element to that list: The ‘I Understand You Moment’, in which readers understand that these two characters are right for each other (even if it takes the characters a little longer to work it out).

What ‘slow burn’ doesn’t mean:

- Unvaried pacing

- An admixture of the different types of pacing which simply doesn’t work

- Misplaced backstory, sacrificing narrative drive

WHY WE GET LARGER THAN LIFE CHARACTERS

All my great characters are larger than life, not realistic. In order to capture the quality of life in two and a half hours, everything has to be concentrated, intensified. You must catch life in moments of crisis, moments of electric confrontation. In reality, life is very slow. Onstage, you have only from 8:40 to 11:05 to get a lifetime of living across.

Tennessee Williams, American playwright (1911 – 1983)

What does Williams mean by ‘larger than life’? In part, I believe he means they react in slightly exaggerated ways. Audiences expect this of fiction.

CONTRAST WITH

Chewing the furniture

This is a term from theatre, used to describe actors who are over-emoting their characters. I suspect when writers miss opportunities to ‘make a bigger deal out of stuff’ they are worried about attracting this criticism.

PACING IN PICTURE BOOKS

Whether an individual picture is static or conveys motion, the more details there are in a picture, the longer its discourse time. The common prejudice is that children do not like descriptions, preferring scenes and dialogue. This must be an acquired preference, imposed on children by adults, since all empirical research shows that children, as well as adults, appreciate picturebook pauses and eagerly return to them.

How Picturebooks Work by Maria Nikolajeva and Carole Scott

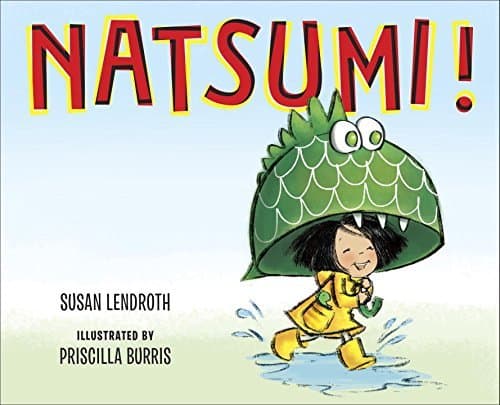

Since picture books are short, some picture books sustain the same pace across most or all of the story. In the example below, the pace of the book has been designed to match the exuberance of the main character. Filled with noise and action, the story paints a character study of a dynamic little kid who just can’t slow down, be quiet or be gentle.

Natsumi is small but full of big exuberance, and puts her girl-power to good use when she discovers a Japanese tradition as energetic as she is.

When Natsumi’s family practices for their town’s Japanese arts festival, Natsumi tries everything. But her stirring is way too vigorous for the tea ceremony, her dancing is just too imaginative, and flower arranging doesn’t go any better. Can she find just the right way to put her exuberance to good use?

This heartwarming tale about being true to yourself is perfect for readers who march to their own beat.

PACING IN COMIC BOOKS

In comic books, when artists constantly change up the camera angles, they sometimes do this to match the vertiginous pace of a story. There are other reasons artists change up the camera angles, of course (to show the psychological state of a character — lost, trapped — or to show power dynamics etc.)

Fiction is a time-based art; the storyteller controls how quickly or slowly time flows. You can cover centuries in a page or two, or slow a single moment down so that it goes on for panels and panels.

Nalo Hopkinson, Jamaican-born Canadian writer of comic books, PanelxPanel magazine

Tim walked in the door, sat down, and ate an apple” is one sentence, but more than one panel!

Kat Howard, comic book writer, PanelxPanel magazine

WRITING TECHNIQUE

Fast forward. The literary convention of shortcutting things the reader already knows but the characters may not. Example: Rex Stout’s Archie Goodwin: “I got home and told Wolfe everything that had happened since I stumbled over Helaine Bradford’s body in Adam Roberts’ room. He grunted occasionally and belched when I was done.”) Especially handy in mysteries. (CSFW: David Smith)

Glossary of Terms Useful In Critiquing Science Fiction

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

French philosopher Henri Bergson had a pretty major revelation regarding time. Thirteen years before Einstein shared his Theory of Relativity, Bergson already understood that we don’t experience time as constant — human time seems to pass more rapidly on some occasions and more slowly on others. He drew a distinction between ‘duration’ and ‘time’ which had not been articulated before.

Pubcrawl Podcast: Writing Mechanics — pacing.

Moreover, French Impressionist painters had already discovered this in their art.

It’s Time for the Slow, Aimless Novel to Get Its Due from Electric Literature

Plotting is hard and writing a synopsis is harder but you’ll thank yourself for writing one because it’s a valuable writing craft tool in disguise.

@agentsaba

Saba Sulaiman goes on to explain how your plot synopsis can alert writers to pacing issues in their manuscripts.