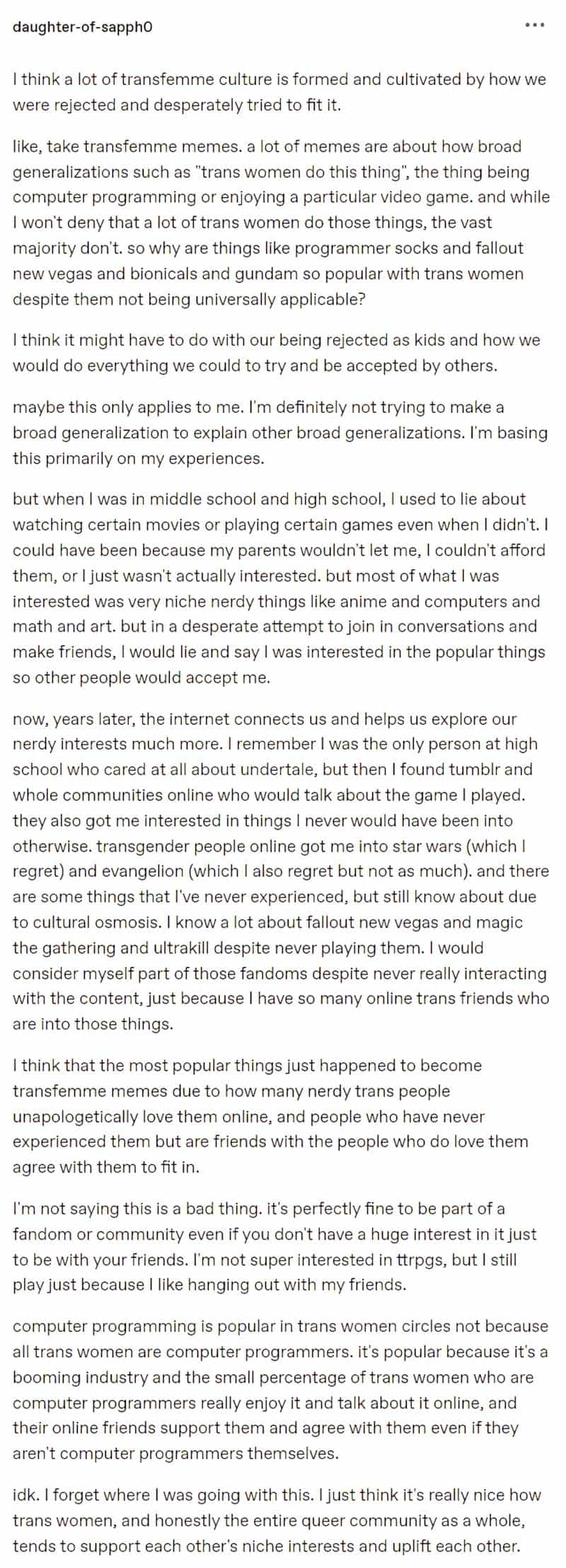

Detransition, Baby is a contemporary novel that hooked me right away.

How did author Torrey Peters create such a great opening? Let’s take a closer look.

A whipsmart debut about three women—transgender and cisgender—whose lives collide after an unexpected pregnancy forces them to confront their deepest desires around gender, motherhood, and sex.

Reese almost had it all: a loving relationship with Amy, an apartment in New York City, a job she didn’t hate. She had scraped together what previous generations of trans women could only dream of: a life of mundane, bourgeois comforts. The only thing missing was a child. But then her girlfriend, Amy, detransitioned and became Ames, and everything fell apart. Now Reese is caught in a self-destructive pattern: avoiding her loneliness by sleeping with married men.

Ames isn’t happy either. He thought detransitioning to live as a man would make life easier, but that decision cost him his relationship with Reese—and losing her meant losing his only family. Even though their romance is over, he longs to find a way back to her. When Ames’s boss and lover, Katrina, reveals that she’s pregnant with his baby—and that she’s not sure whether she wants to keep it—Ames wonders if this is the chance he’s been waiting for. Could the three of them form some kind of unconventional family—and raise the baby together?

This provocative debut is about what happens at the emotional, messy, vulnerable corners of womanhood that platitudes and good intentions can’t reach. Torrey Peters brilliantly and fearlessly navigates the most dangerous taboos around gender, sex, and relationships, gifting us a thrillingly original, witty, and deeply moving novel.

Marketing copy for Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

Backstory

Painting the setting

CHAPTER ONE: One month after conception

THE QUESTION, FOR Reese: Were married men just desperately attractive to her? Or was the pool of men who were able to her as a trans woman only those who had already locked down a cis wife and could now “explore” with her? The easy answer, the one that all her girls advocated, was to call men dogs. But now, here’s Reese, sneaking around with another handsome, charming, mothervucking cheater. Look at her, wearing a black lace dress and sitting in his parked Beamer, waiting while he goes into a Duane Reade to buy condoms. Then she’s going to let him come over to her apartment, avoid the pointed glare of her roommate, Iris, and have him fvck her right on the trite floral bedspread that the last married dude bought her so that her room would seem a little more girly and naughty when he snuck away from his wife.

If you’ve read The Sex Myth by Rachel Hills you may argue that sex acts, in their own right, don’t actually tell us much about people. It’s people’s reactions, rather than acts, which afford the ‘telling’ details. Cheap ways to open a novel: With near-death action scenes and sex. Satisfying ways to open a novel: Deep characterisation. Characterisation can come from a sex scene, of course, and that’s what Torrey Peters does here. From the very first sentence, we can tell this book is a character study. (Actually there are two main character studies. Further down, we are introduced to Ames).

So much is packed into this opening paragraph. The direct address to the reader (Look at her) affords an ekphrastic feel: we are looking at a scene as if on a painting (or gif). Equally, the phrase, ‘Look at her’ could be the voice of jealous, judgemental, unnamed onlookers. “She’s all that.” The worst thing a woman could be. This entire novel is an exploration of femininity. It’s introduced right off the bat, with the suggestion that a true woman must hate herself. Reese defies womanhood in several ways. In this opening paragraph, she goes against ‘woman culture’ by giving ‘dogs’ what they want. The snippets of backstory convey a pattern of behaviour as well as setting up the social dynamics of Reese’s world.

Reese had already diagnosed her own problem. She didn’t know how to be alone. She fled from her own company, from her own solitude. Along with telling her how awful her cheating men were, her friends also told her that after two major breakups, she needed time to learn to be herself, by herself. But she couldn’t be alone in any kind of moderate way. Give her a week to herself and she began to isolate, cultivating an ash pile of loneliness that built on itself exponentially, until she was daydreaming about selling everything and drifting away on a boat toward nowhere. To jolt herself back to life, she went on Grindr, or Tinder, or whatever—and administered ten thousand volts to the heart by chasing the most dramatic tachycardia of an affair she could find. Married men were the best for fleeing loneliness, because married men also didn’t know how to be alone. Married men were experts at being together, at not letting go, no matter what, until death do us part. With the pretense of setting the boundaries of “just an affair,” Reese would swandive super deep, super hard. By telling herself it would just be a fling, she gave herself permission to fulfill every fetish the guy had ever dreamed of, to unearth his every secret hurt, to debase herself in the most lush, vicious, and unsustainable ways—then collapse into resentment, sadness, and spite that it had been just a fling, because hadn’t she been brave enough and vulnerable enough to dive super deep, super hard?

The interesting thing about Reese, already, is that she is old enough to be somewhat self-aware. This is not your typical middle-aged coming-of-age novel. (Coming out stories are coming-of-age novels, no matter the age of the character.) There are few stories about trans people, and even fewer about middle-aged trans people whose personal development involves far more subtle revelations than, “Oh, I’m trans.” Reese’s transness is crucial to the story but is not intrinsic to the character arc. The development Reese experiences in this story is common to other middle aged people of any gender. The first sentence of this paragraph tells readers this story will be about reassessing community in middle-age. Are the people you’ve been travelling with thus far about to serve you well here on in? Do you go back to your old familars, or do you find yourself a new family?

There’s plenty of foreshadowing in this paragraph as well. Reese’s daydream about ‘floating away’ will come full circle near the end.

The narrator has told us how Reese assesses herself, and her issues. As the paragraph progresses, the narrative voice zooms away from Reese’s head. We’re no longer inside it. This assessment of her character does not necessarily come from Reese. We’ll find out as the novel progresses the extent of any gap between Reese’s self-assessment and her ‘true’ character. We can assume characters will be wrong about something at the beginning of a story. It’s possible she’s correct about married men (in the universal sense) but incorrect about how much damage they are doing to her life.

She saw herself as attractive, round face and full figure, but she didn’t pretend that she stopped traffic; nor did she frequently note people standing around to admire the harvests of her brain. But with the right kind of man, she bore a genius for drama. She could distill it and flame it like jet fuel when solitude chilled her bones.

The beginning of this paragraph, again, describes how Reese sees herself, but then the narrator zooms out. By the time we’ve reached the final sentence of this paragraph, this could now be a (unusually poetic) therapist speaking. We’re getting Reese’s psychological shortcoming, moral shortcoming and also her strengths served to us via narration. This only works because Reese is a fascinating character, unlike character tropes we’ve seen many times before. Normally authors would show a character’s shortcomings via a scene, and let readers assess character for ourselves. There’s always a danger in doing that, of course; readers can’t always be trusted to avoid prejudice and stereotyping even when reading fiction. When writing a character with a marginalised identity (in this case a trans woman) it’s a safer strategy to have an unseen narrator explain character in a series of thumbnail sketches. (By the way, there’s no need to make a character walk past a reflective surface such as a mirror before letting a narrator simply describe them.)

Her man this time was similar to her others. A handsome, married alpha-type who put her on a leash in the bedroom. Only this one was better, because he was an HIV-positive cowboy-turned-lawyer. He had a thing for trans girls and had seroconverted while cheating on his wife with a trans woman, and the wife had stayed with him, and now he was at it again with Reese. Wheeeee!

In children’s stories, especially the older ones, stories begin with a description of what happens all the time, then switches to what happens today. This has been called the switch from the iterative to the singulative. Books for adults do this, too. Until this point, Peters has described a pattern of behaviour; what Reese does ‘every day’. With this paragraph, however, the author moves readers closer towards the story to be told in this particular book: ‘Her man THIS TIME…’ is similar to Then, ONE DAY…

Torrey Peters wrote this novel for herself and her trans friends, not really expecting to get it published. (The publishing landscape changed very quickly.) So she doesn’t stop to explain concepts such as seroconverted, which the straight, non-HIV community will have to work out. That’s okay; there’s always Google. We’re allowed to write for niche audiences without explaining ourselves, or writing primers.

The reader doesn’t know at this point that the HIV status of the cowboy will be vital information later, contributing to a turning point in the plot. Introduced so early, details are sometimes forgotten, so if writers mean readers to remember certain details, the details must be packaged in a memorable way. Torrey Peters succeeds in this. This packaging ensures we remember the guy. He is painted so vividly.

“Did you bottom or something?” Reese had asked on their first date.

For all its deep, and often painful characterisation, this is a funny novel. This is the first snippet of dialogue readers hear. Interestingly, the author doesn’t ground readers by telling us where they are on their date when this dialogue is happening. Normally, as a rule of thumb, readers need to be grounded in time and space. But it works here. I’m not even asking where they are. They are talking heads, floating around in space and I’m fine with it. I only want to know what happens next. (Perhaps you’re imagining them at a restaurant, or walking along a pier — somewhere ‘date-like’.)

“Fvck no,” he said. “My doctors said I had a one in ten thousand chance to contract it from getting head. You figure that at least ten thousand blow jobs are happening every minute, but that one in ten thousand was me. Also, she gave me a lot of blow jobs.”

Writers, start as you mean to go on. Readers, if this language is not for you, you’ll know it from page two. That said, it would be a mistake to open with a swear word. I’ve seen someone open with ‘Fvck’ in a piece submitted to a writing critique group. That writer was roundly dismissed for trying too hard to be edgy. Writers need to earn the right first.

“Cool,” said Reese, who knew that that explanation wasn’t factual, but had only really agreed to make sure he wasn’t going to try to bottom with her. Within the hour, she had him back in her room and confessing from whom he’d gotten HIV and where.

Readers tend to despise liars, so we now despise Reese’s cowboy. In contrast we like Reese very much, for her ability to see through his bullshit, and also for her ability to get the truth out of him. This is Reese’s main strength, her ability to cut through facades.

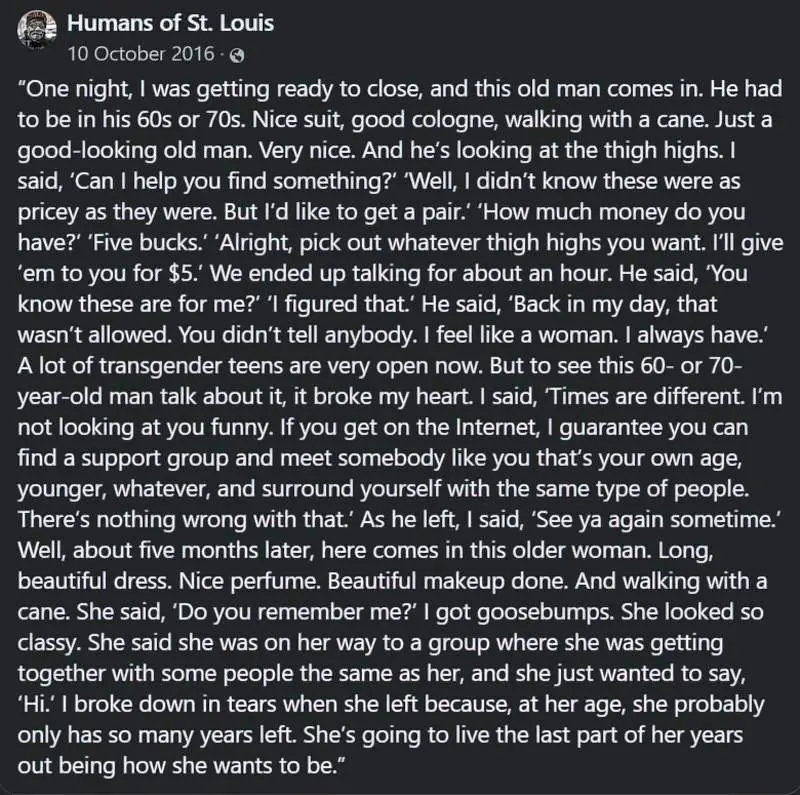

The worst thing you can do, as someone who has recently realised they are transfem, is to let terves and transphobes convince you cis women will never accept you.

I was told that when I came out everyone would reject me. That I would find myself isolated from the world, and from other women especially, who would react to me with horror and revulsion.

In reality, within the first months of coming out, in no particular order:

My sister’s reaction on my coming out was, “Right, so I have a sister instead of a brother. Cool. I’m taking you clothes shopping tomorrow.”

A friend, when she learned I am a woman, immediately invited me to her women-only, girls-night-out birthday party the following week.

Another friend, when a friend of hers expressed doubts about my gender, immediately shut them down and reaffirmed I am a woman.

I went camping with a group of friends, and we had two tents, one for the boys and one for the girls; I was unsure as to which I should enter, to which a girl friend responded by grabbing me and physically dragging me inside the women’s tent.

In the women’s bathroom at a movie theatre a random woman, whom I’d never seen before and haven’t seen since, stopped me as I was going into a stall, to warn me there was no toilet paper in there, because she’d just used the last of it.

All of these, and more, some from friends, some from complete strangers. All within a few months, as a trans woman who hadn’t started medical transition yet, and was very visible as being a trans woman.

I’ve had some people reject me, true, but the vast majority, including almost all cis women, accepted me as a sister with open arms.

Cis women are cool. It’s terves who are bigots.

zoestorm on Tumblr