The openings to stories by Kazuo Ishiguro are on the challenging side. Ishiguro writes for readers who persevere with a slow-burn mystery, who appreciate stories with gaps. It can be fun to fill in the gaps. Let’s take a close look at Never Let Me Go (2005). Naturally, a story can have too many gaps. All readers need to feel supported. So what’s the balance of information to mysterious hook? Never Let Me Go is a case study in perfect balance.

Backstory

Flash forward

Painting the setting

More than usual for a storytelling website, I recommend reading this post only if you’ve already read the entire book.

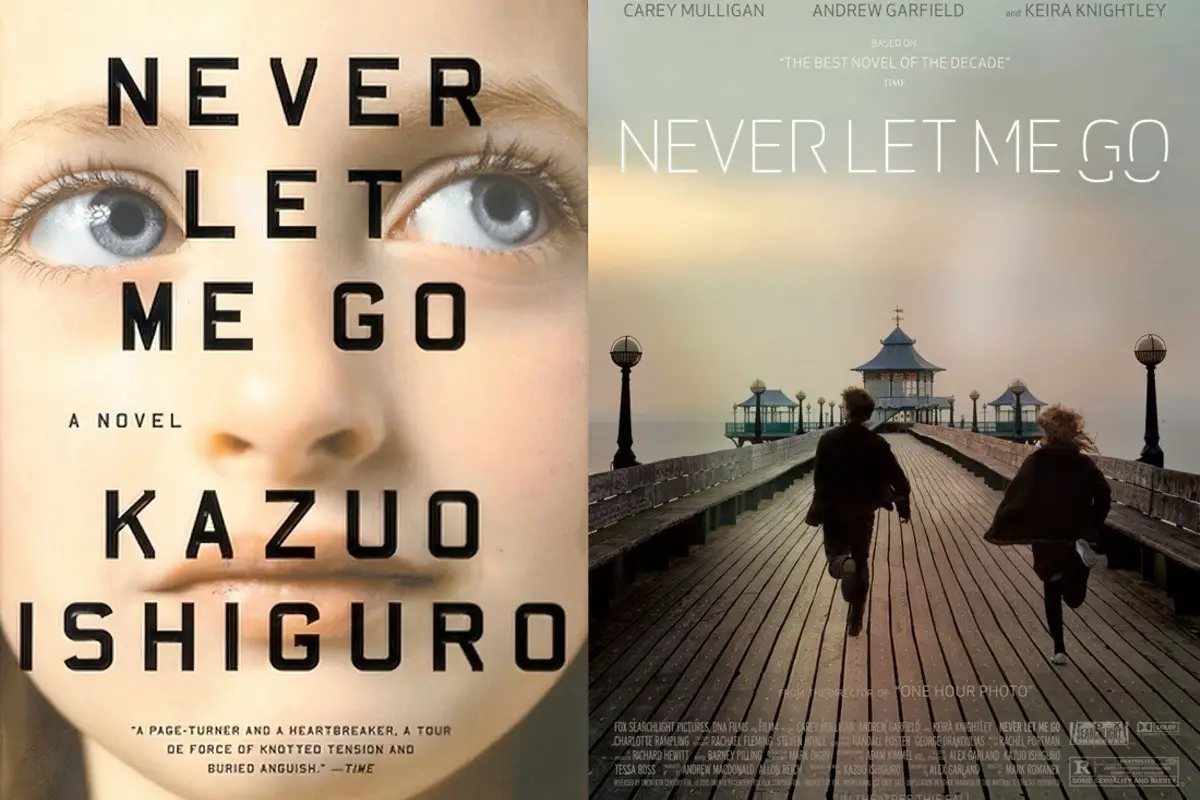

Shortlisted for the 2005 Booker Prize

Kazuo Ishiguro imagines the lives of a group of students growing up in a darkly skewed version of contemporary England. Narrated by Kathy, now thirty-one, Never Let Me Go dramatises her attempts to come to terms with her childhood at the seemingly idyllic Hailsham School and with the fate that has always awaited her and her closest friends in the wider world. A story of love, friendship and memory, Never Let Me Go is charged throughout with a sense of the fragility of life.

Marketing copy

CHAPTER ONE

My name is Kathy H. I’m thirty-one years old, and I’ve been a carer now for over eleven years. That sounds long enough, I know, but actually they want me to go on for another eight months, until the end of this year. That’ll make it almost exactly twelve years. Now I know my being a carer so long isn’t necessarily because they think I’m fantastic at what I do. There are some really good carers who’ve been told to stop after just two or three years. And I can think of one carer at least who went on for all of fourteen years despite being a complete waste of space. So I’m not trying to boast. But then I do know for a fact they’ve been pleased with my work, and by and large, I have too. My donors have always tended to do much better than expected. Their recovery times have been impressive, and hardly any of them have been classified as ‘agitated’, even before fourth donation. Okay, maybe I am boasting now. But it means a lot to me, being able to do my work well, especially that bit about my donors staying ‘calm’. I’ve developed a kind of instinct around donors. I know when to hang around and comfort them, when to leave them to themselves; when to listen to everything they have to say, and

when just to shrug and tell them to snap out of it.

If you’re writing a thing and stressing that your first sentence isn’t clever or witty enough, a first sentence such as this in a great work should offer solace.

The opening establishes the first person narrator’s chatty voice.

Readers familiar with Ishiguro will know to expect that words don’t mean what they seem to on the surface. ‘Carer’ doesn’t just mean ‘carer’ as we know it in the real world.

Ishiguro alerts us to this very early, in the first paragraph: ‘There are some really good carers who’ve been told to stop after just two or three years.’

Also, what is a ‘donor’? The slow reveal: all “donors” receive care from designated “carers,” clones who have not yet begun the donation process. Note that if Ishiguro had used the word ‘clone’, this would ruin the reveal.

This is all very confusing for the reader, accustomed to ‘carers’ looking after elderly and disabled people. Even readers coming to the book knowing vaguely what it’s about will feel discombobulation. (The older the story, the more likely readers arrive with the basic premise. More so after a book has been adapted to film.)

Perhaps ‘defamiliarisation‘ is a better word. This is why I say Ishiguro attracts and retains readers who enjoy a slow burn mystery thread.

Anyway, I’m not making any big claims for myself. I know carers, working now, who are just as good and don’t get half the credit. If you’re one of them, I can understand how you might get resentful – about my bedsit, my car, above all, the way I get to pick and choose who I look after. And I’m a Hailsham student – which is enough by itself sometimes to get people’s backs up. Kathy H., they say, she gets to pick and choose, and she always chooses her own kind: people from Hailsham, or one of the other privileged estates. No wonder she has a great record. I’ve heard it said enough, so I’m sure you’ve heard it plenty more, and maybe there’s something in it. But I’m not the first to be allowed to pick and choose, and I doubt if I’ll be the last. And anyway, I’ve done my share of looking after donors brought up in every kind of place. By the time I finish, remember, I’ll have done twelve years of this, and it’s only for the last six they’ve let me choose.

In this paragraph, we learn the implied narratee (Kathy’s fellow Hailsham students, or those a little younger). Skilfully, Ishiguro turns the reader into the implied narratee. This novel asks us how we, ourselves, would feel if we’d been born to provide body parts for someone with more power and money. By extension, the story asks us to consider the ways in which our own education has conditioned us to accept inequalities, and smaller lives for ourselves.

K.M. Weiland explains why opening with a ‘characteristic moment’ is important for a story. First impressions count, even in fiction. (Probably even more so, actually, since the reader understands a work of fiction is a contrived simulacrum of a person.) We might expect that, as part of her character arc, she interrogates the assumption that she is a lucky person.

Characteristic of Kathy H: She feels like a lucky person. She is comparing herself to peers rather than to the true lucky people of her world.

And why shouldn’t they? Carers aren’t machines. You try and do your best for every donor, but in the end, it wears you down. You don’t have unlimited patience and energy. So when you get a chance to choose, of course, you choose your own kind. That’s natural. There’s no way I could have gone on for as long as I have if I’d stopped feeling for my donors every step of the way. And anyway, if I’d never started choosing, how would I ever have got close again to Ruth and Tommy after all those years?

Another hook: ‘your own kind’. What does this mean?

This paragraph introduces two other major characters by name only: Ruth and Tommy.

But these days, of course, there are fewer and fewer donors left who remember, and so in practice, I haven’t been choosing that much. As I say, the work gets a lot harder when you don’t have that deeper link with the donor, and though I’ll miss being a carer, it feels just about right to be finishing at last come the end

of the year.

This is the third time Ishiguro mentions the upcoming event in Kathy’s life (highlighted in orange as a flash-forward). Now he puts a specific time on it, which will drive the rest of the narrative. Kathy has less than a year and then something major will happen in her life.

‘Of course’ reminds us that we, the reader, are donors ourselves. We already know this, in the world of the story.

Ruth, incidentally, was only the third or fourth donor I got to choose. She already had a carer assigned to her at the time, and I remember it taking a bit of nerve on my part. But in the end I managed it, and the instant I saw her again, at that recovery centre in Dover, all our differences – while they didn’t exactly vanish – seemed not nearly as important as all the other things: like the fact that we’d grown up together at Hailsham, the fact that we knew and remembered things no one else did. It’s ever since then, I suppose, I started seeking out for my donors people from the past, and whenever I could, people from Hailsham.

Words such as ‘incidentally’ coax the reader into thinking this is an off-the-cuff story when the opening to any novel is anything but.

‘All our differences’ tells us that Ruth is a friend as well as Kathy’s story-worthy opponent. What have they been ‘differing’ on?

I’ve heard writers point out that if you want to weave in backstory, do it during an argument. This advice is so often used that once you notice it, it’s everywhere. It pulls you out of a story (especially on screen).

Ishiguro uses a version of it here. In alluding to their differences, he sneaks in the basic facts about Ruth.

In this paragraph we learn that Cathy has already been proactive. Her plan, before the story even starts, was to seek out her own donors to care for rather than let donors be assigned. (Readers enjoy a proactive main character, where the story allows.)

There have been times over the years when I’ve tried to leave Hailsham behind, when I’ve told myself I shouldn’t look back so much. But then there came a point when I just stopped resisting. It had to do with this particular donor I had once, in my third year as a carer; it was his reaction when I mentioned I was from Hailsham. He’d just come through his third donation, it hadn’t gone well, and he must have known he wasn’t going to make it. He could hardly breathe, but he looked towards me and said: ‘Hailsham. I bet that was a beautiful place.’ Then the next morning, when I was making conversation to keep his mind off it all, and I asked where he’d grown up, he mentioned some place in Dorset and his face beneath the blotches went into a completely new kind of grimace. And I realised then how desperately he didn’t want reminded. Instead, he wanted to hear about Hailsham.

At this point the story switches to backstory, which is better described using the language of diegetic levels. Kathy H. tells us a story (which frames everything that led up to here). Let’s call this Level 1. The main story is the story she tells us. Let’s call that Level 0. At some point, we can expect Cathy to stop telling us the story and bring us into her present, in which the Big Thing (already mentioned) happens to her.

So over the next five or six days, I told him whatever he wanted to know, and he’d lie there, all hooked up, a gentle smile breaking through. He’d ask me about the big things and the little things. About our guardians, about how we each had our own collection chests under our beds, the football, the rounders, the little path that took you all round the outside of the main house, round all its nooks and crannies, the duck pond, the food, the view from the Art Room over the fields on a foggy morning. Sometimes he’d make me say things over and over; things I’d told him only the day before, he’d ask about like I’d never told him. ‘Did you have a sports pavilion?’ ‘Which guardian was your special favourite?’ At first I thought this was just the drugs, but then I realised his mind was clear enough. What he wanted was not just to hear about Hailsham, but to remember Hailsham, just like it had been his own childhood. He knew he was close to completing and so that’s what he was doing: getting me to describe things to him, so they’d really sink in, so that maybe during those sleepless nights, with the drugs and the pain and the exhaustion, the line would blur between what were my memories and what were his. That was when I first understood, really understood, just how lucky we’d been – Tommy, Ruth, me, all the rest of us.

So I won’t keep with the yellow highlighting, because we’re in the main story now. (We have been for a whole paragraph already.)

Keeping with the language of diegetic levels, now someone in Level 0 asks Kathy to tell him a story. Now we’re talking diegetic Level -1. (A story within a story.) It hasn’t taken Ishiguro long to create narrative complexity.

But does the reader even notice? No. It’s done so well, using conversational language.

The story Kathy tells him is the story of Hailsham. Not sure about you, but I’m desperate to hear more about Hailsham, first introduced, only later described. Ishiguro efficiently kicks off with a list of features, some of them ‘telling’ details. (It feels like a wealthy estate.) Others are mysterious. (What is a ‘collection chest’? What is a ‘guardian’ in this context?)

Also what is ‘completing’? The reader can guess this is euphemistic. But we don’t know if it means death or something death-adjacent.