The ability to depict movement is perhaps the most important skill of a picture book illustrator. The same goes for comic book illustrators. But not everything is all about movement. Although a professional illustrator has to be good at depicting movement, there is a time and a place for ‘stills’, even inside ‘high-movement’ stories.

Below I take a look at examples of still images in picture book illustration.

AN EXAMPLE FROM COMICS

I was writing NYX, which was a Marvel book about these teenage mutants who are living on the streets of New York. And [the character] Kiden, one of her powers is that she can stop time. I remember the editor writing, “This is not a film. So how do you guide an artist when it comes to describing stopped time? Because literally everything is already stopped on the page.” That was a real eye-opener to how this was a very deep medium I was working in.

from an interview with Marjorie Liu, creator of Monstress

CHARACTERS POSING FOR ‘PHOTOS’ IN PICTURE BOOKS

This is how my eight year old tends to begin her homemade picture books:

Professional picture book illustrators, on the other hand, know all about movement, and are able to convey in a static image a wide variety of verbs that are happening within a scene.

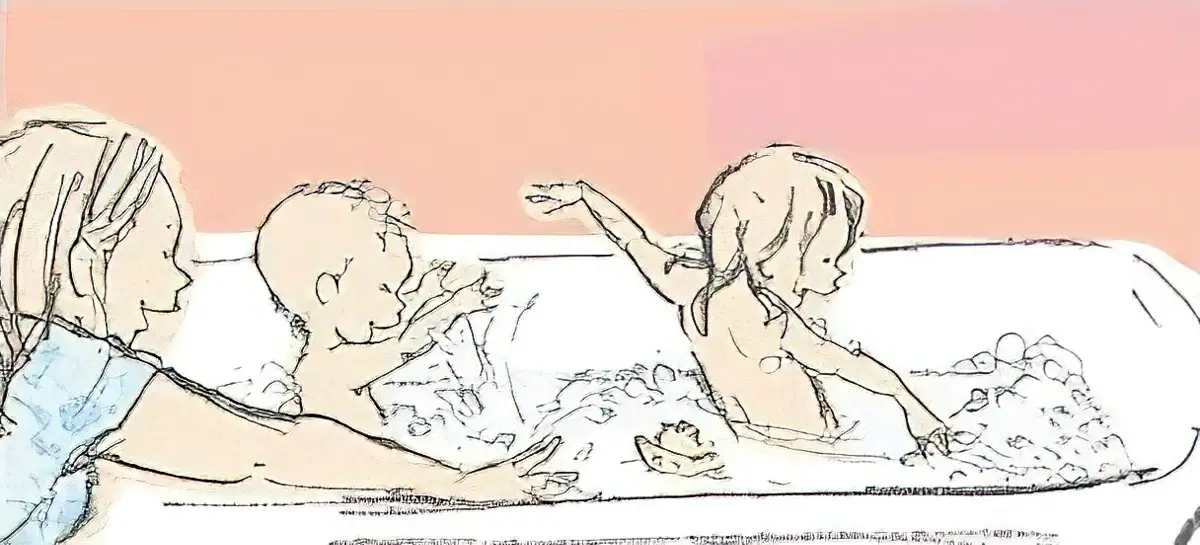

Rudie Nudie by Emma Quay is an example of a picture book in which movement is very important and expertly depicted. A loose, sketchy, generic style of illustration is very good for ‘high-movement’ illustrations, with realism best saved for sombre, more serious stories.

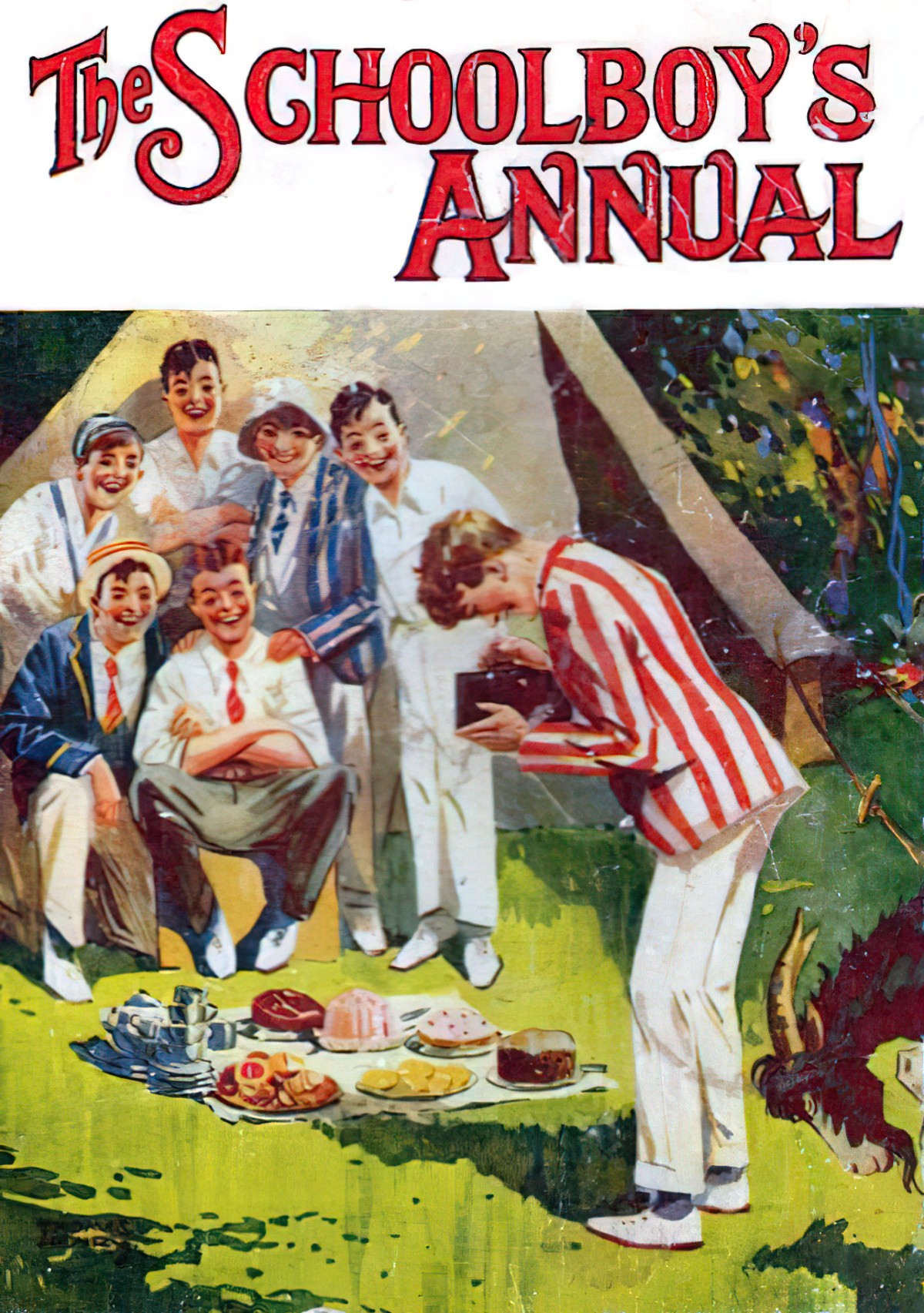

Where do we most commonly find ‘still’ images inside a picture book? On the front cover. Oftentimes, the characters look as if they have posed for a photograph. This isn’t always the best choice for a story — the most tragic example lately would have to be a family of inappropriately smiling black slaves. Aside from this race issue, there are also feminist issues here — girls are more likely to be depicted still and smiling than boys.

Smile, baby! You’re on the cover of a picture book!

WHEN A NEW CHARACTER IS INTRODUCED

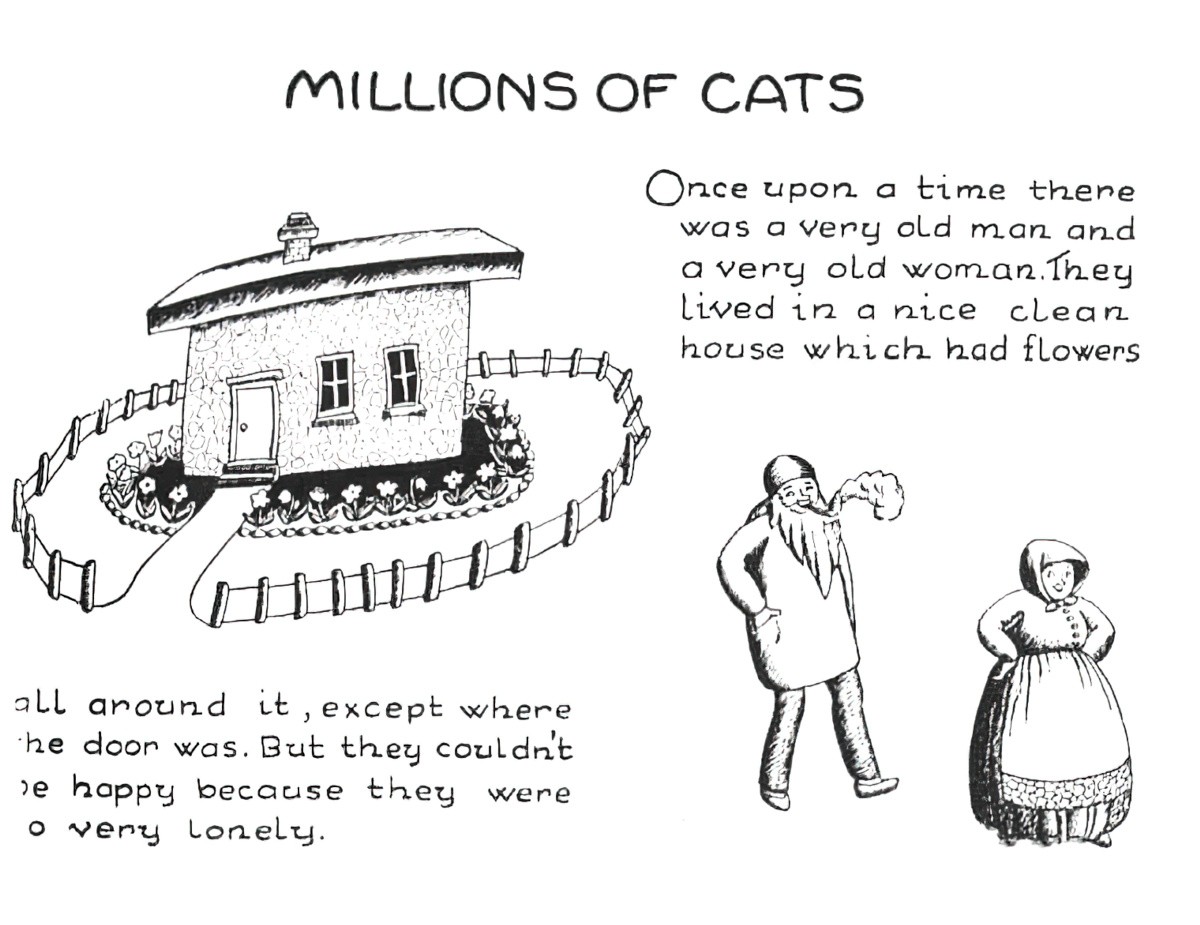

This often happens on page one, for example in Wanda Gag’s Millions of Cats. To the left we see the basic setting — a somewhat lopsided little cottage, and to the right we see the main human characters… and they’re not actually doing anything related to the narrative. They seem to be standing there precisely so they can be introduced to us.

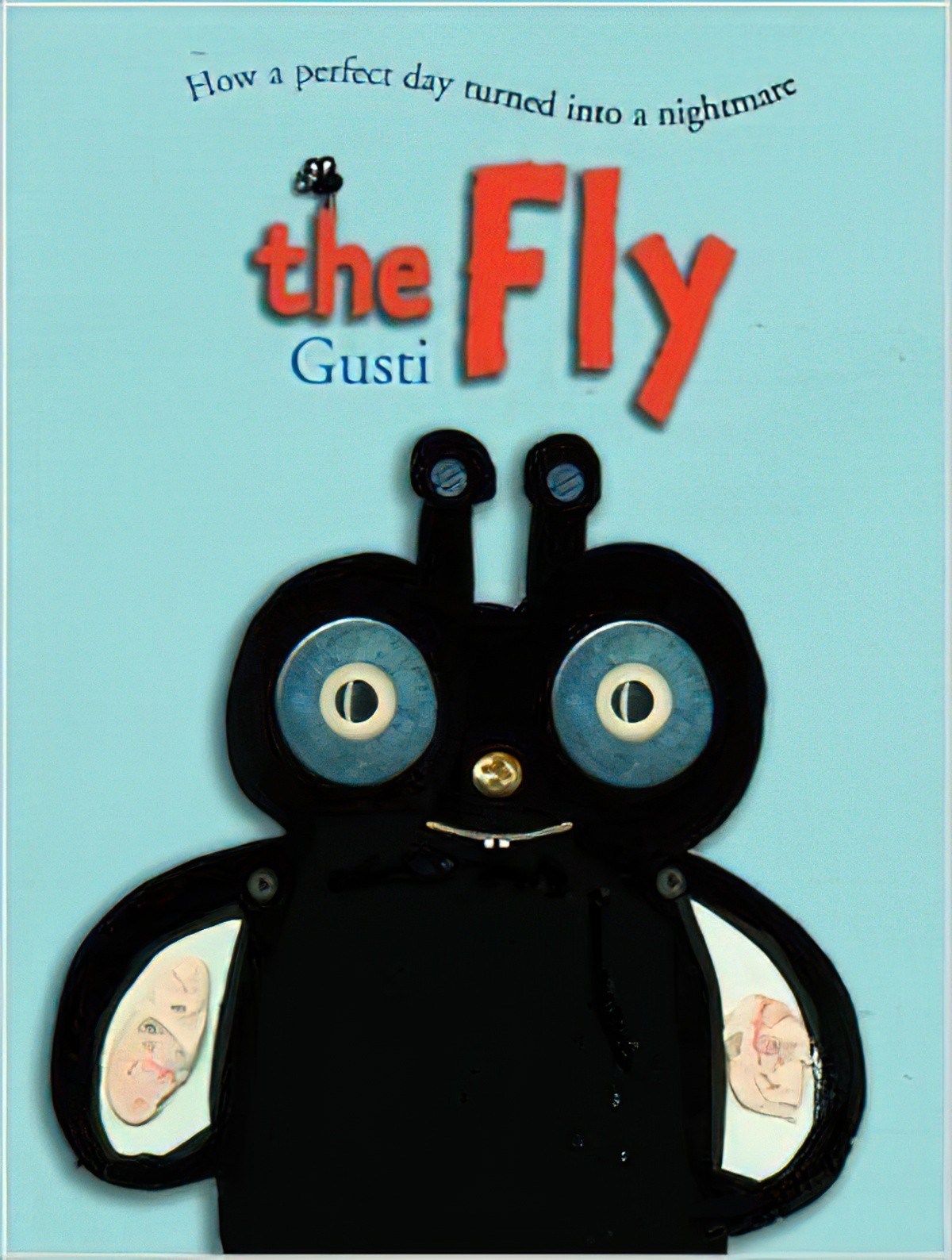

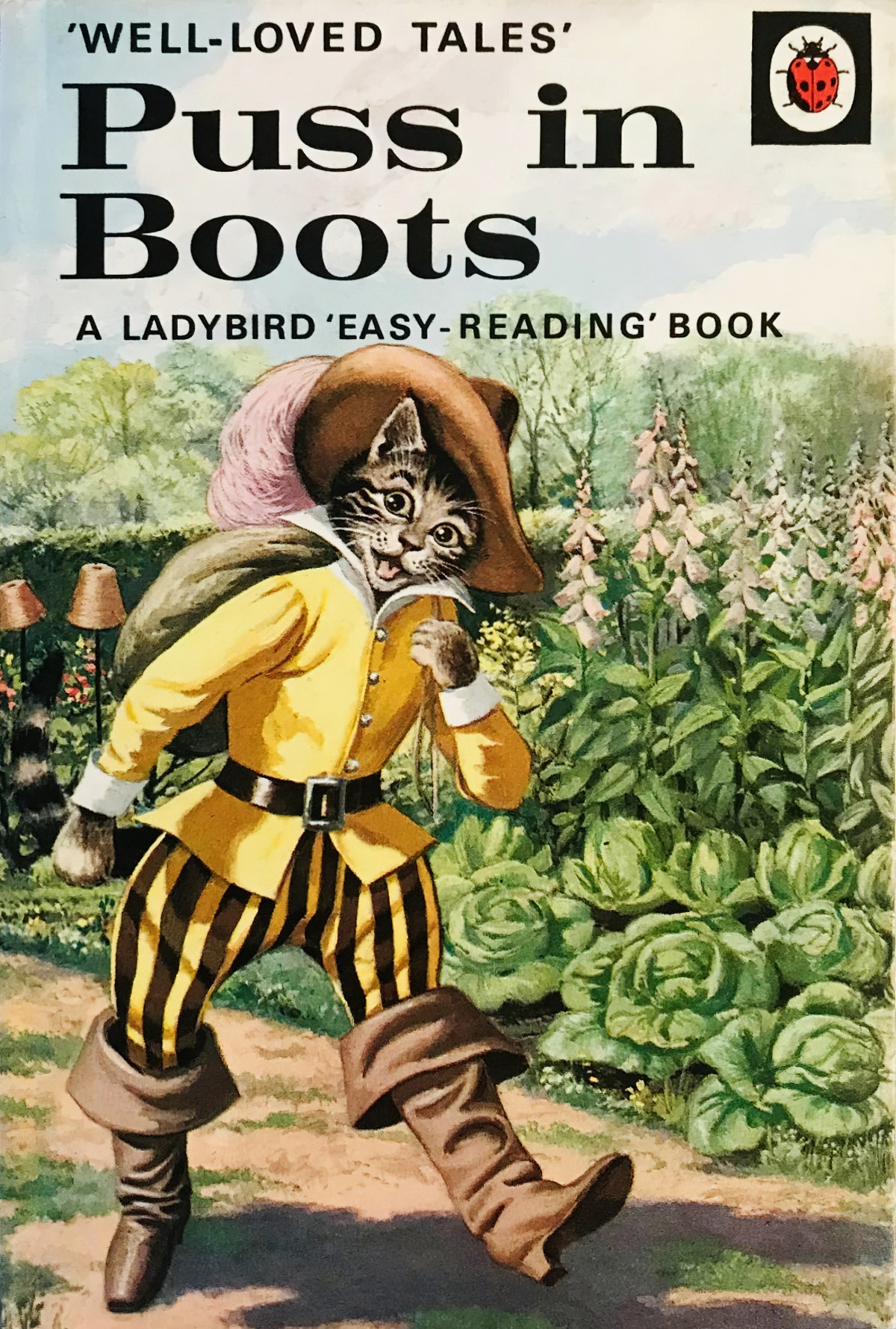

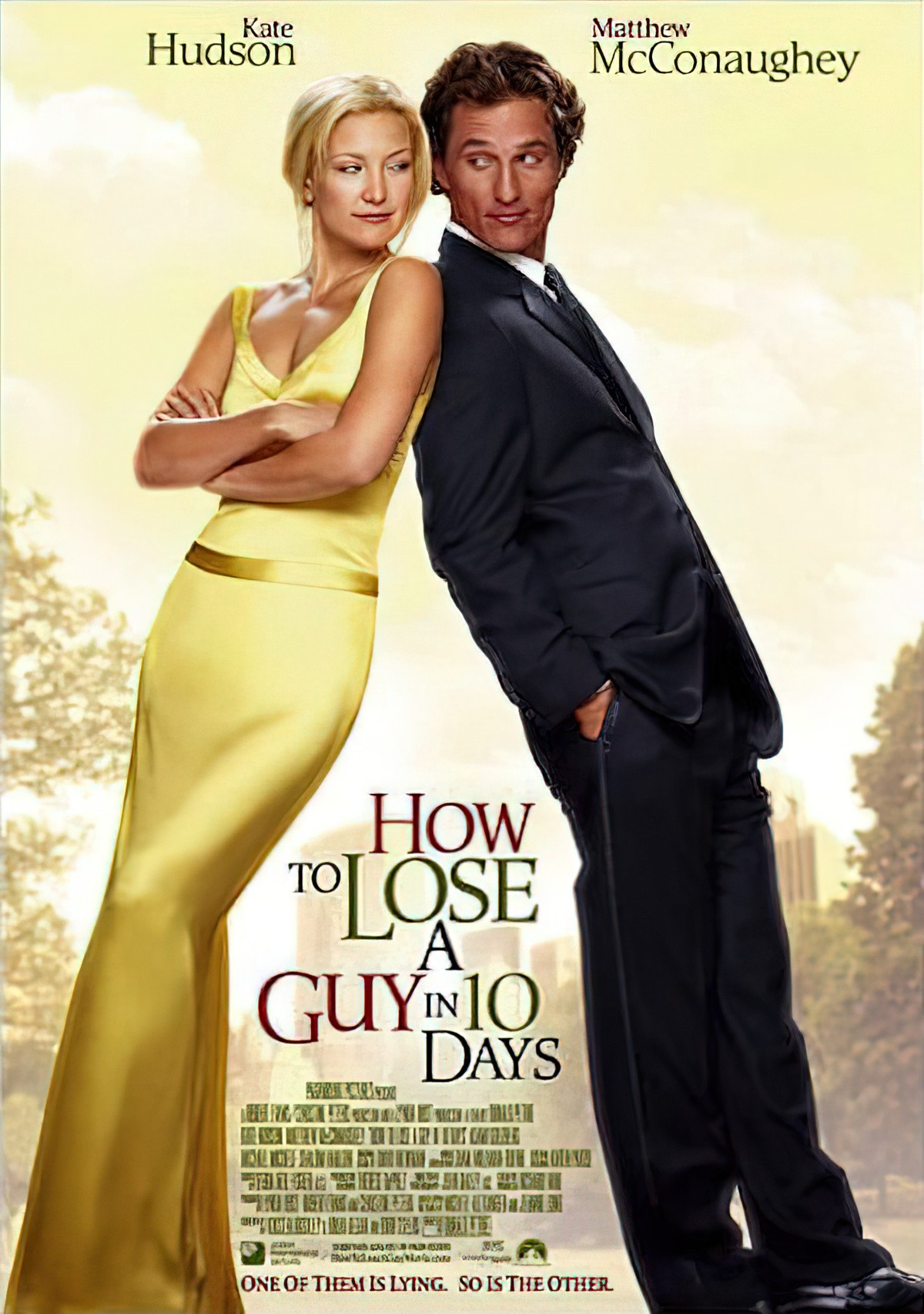

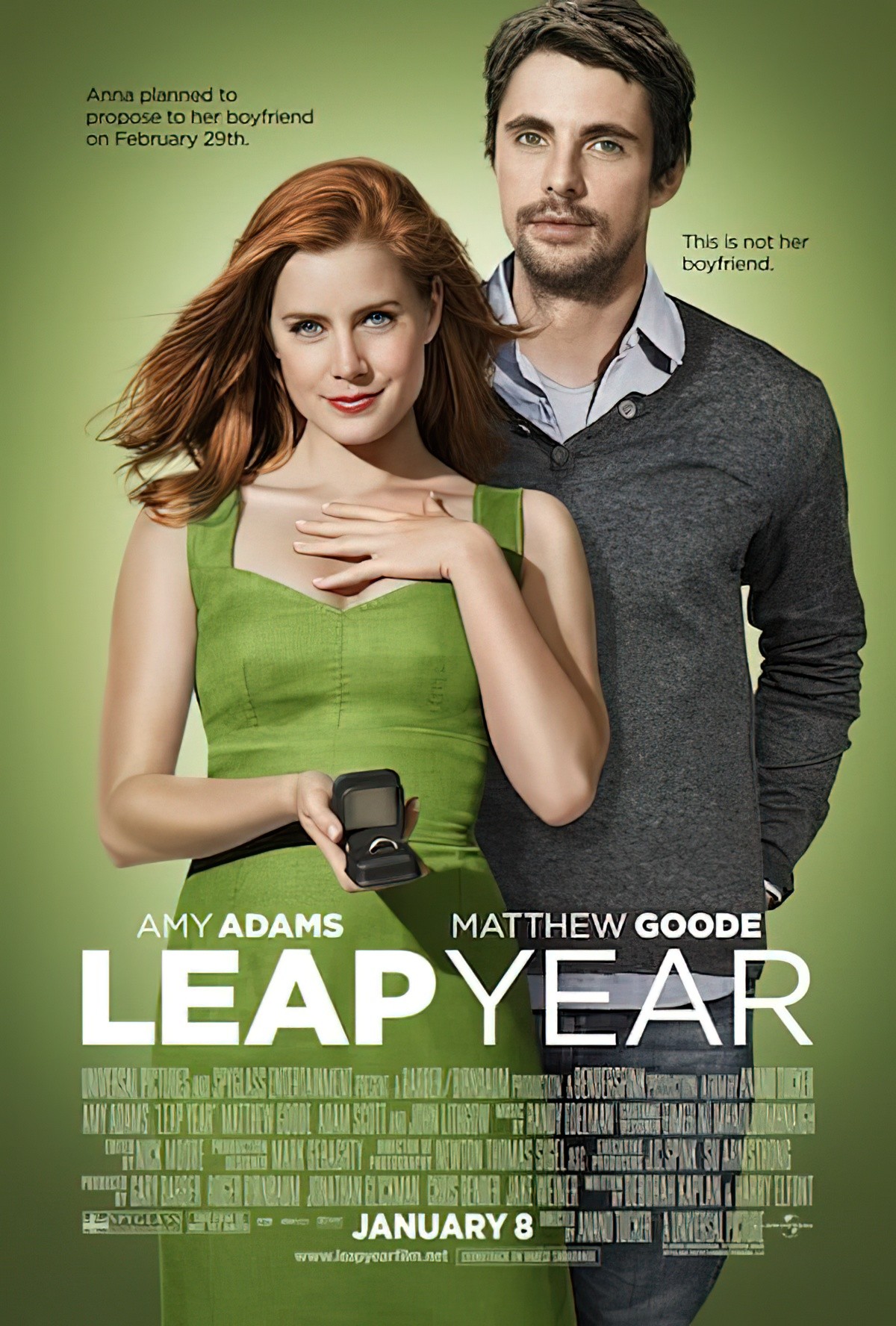

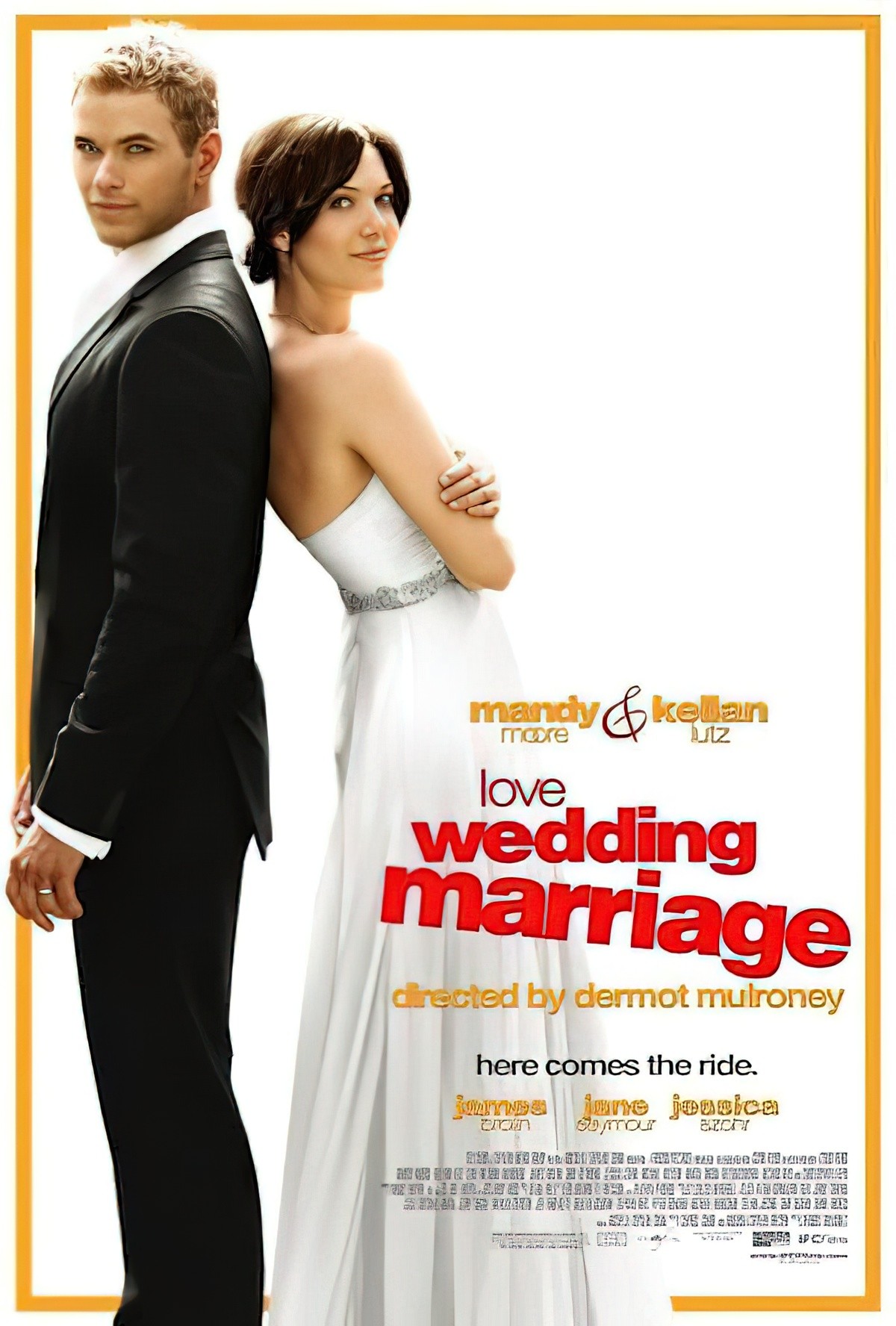

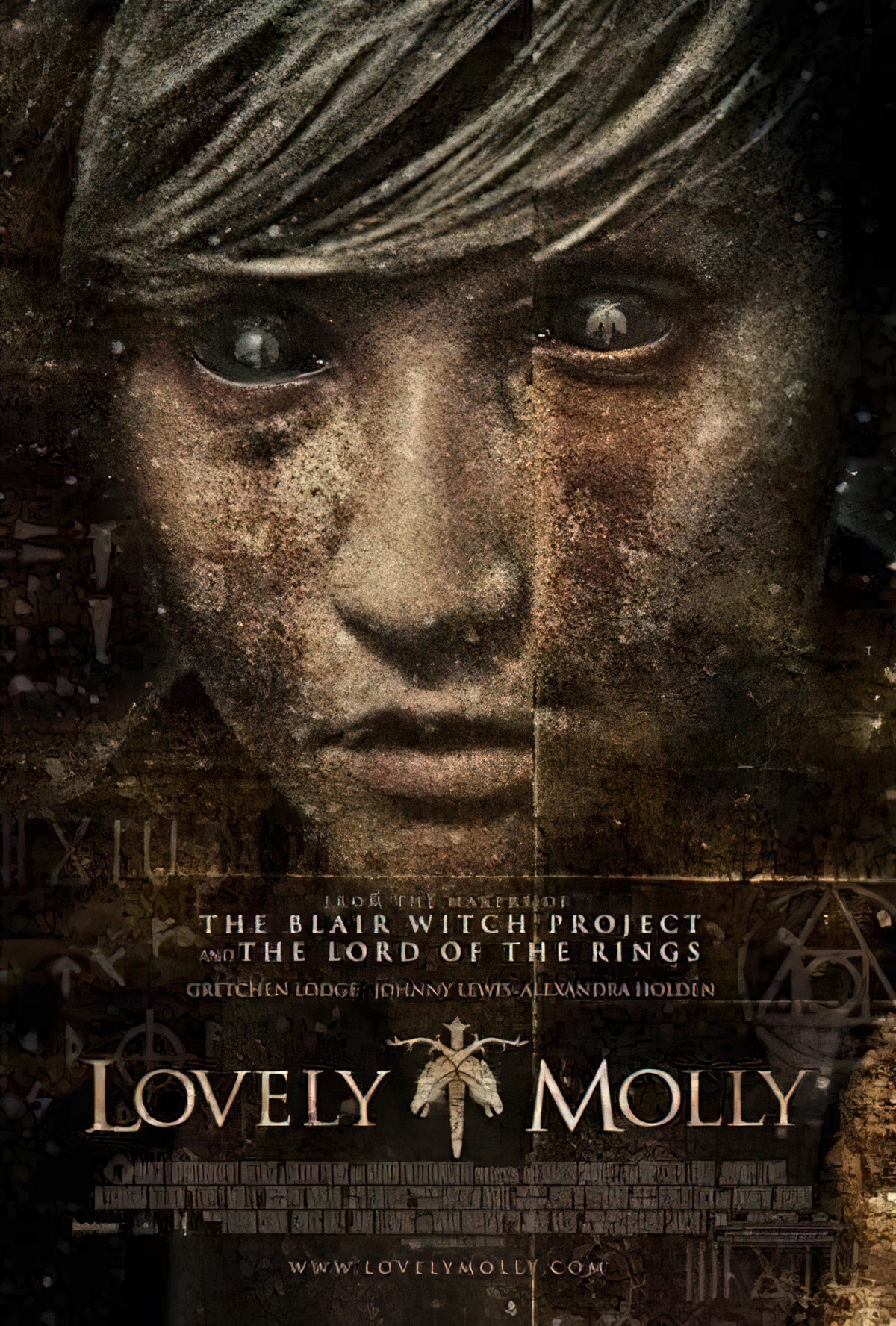

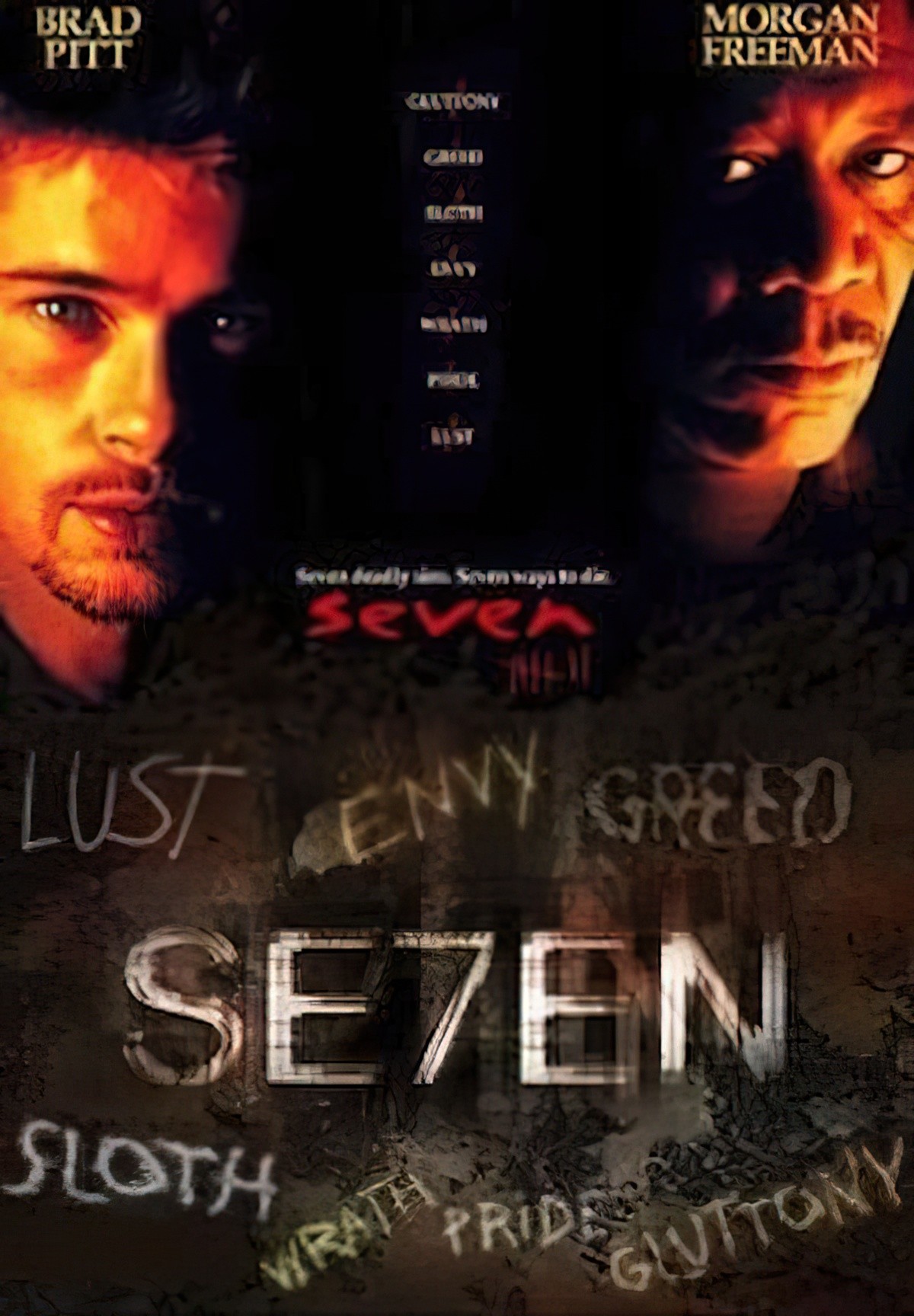

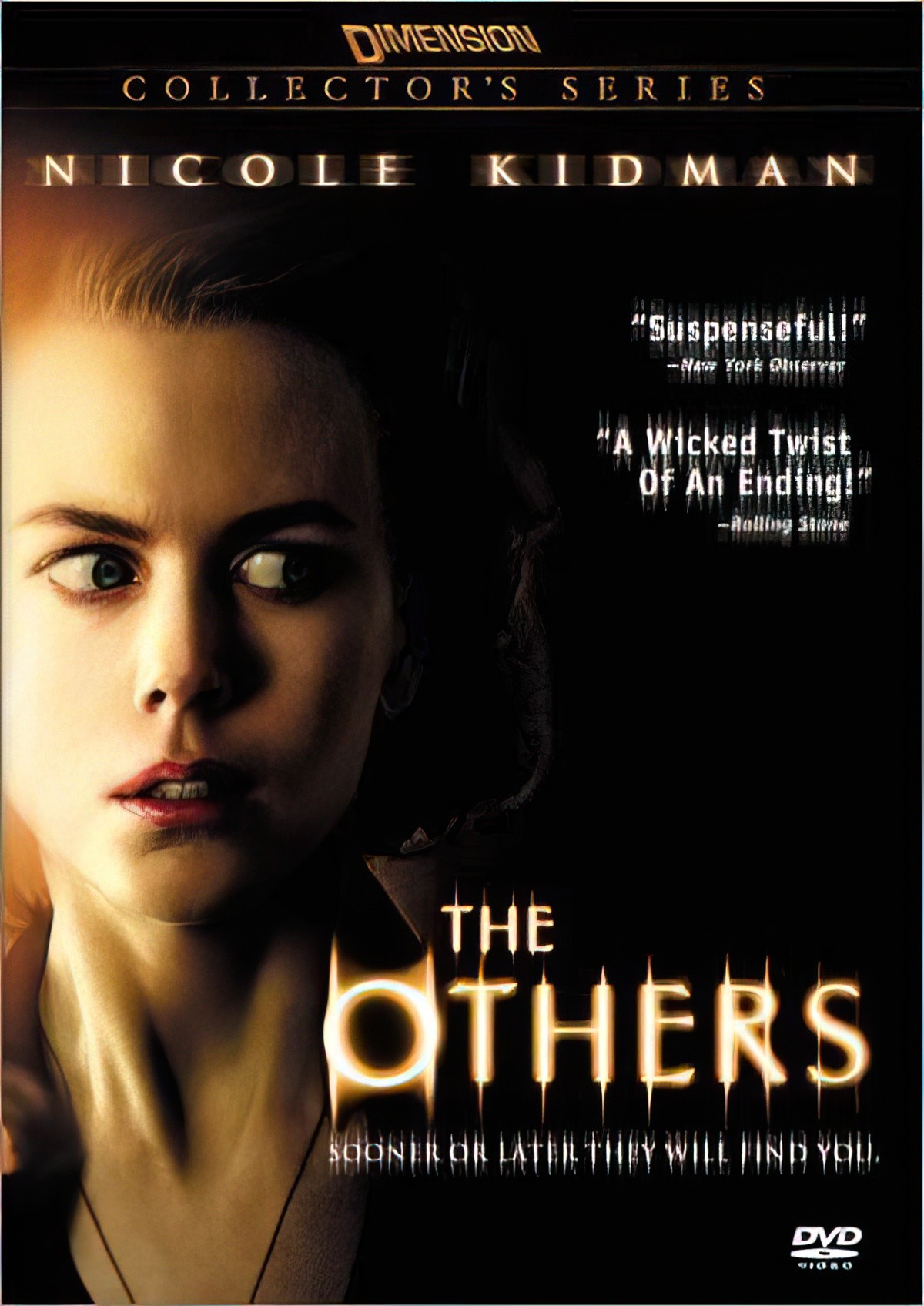

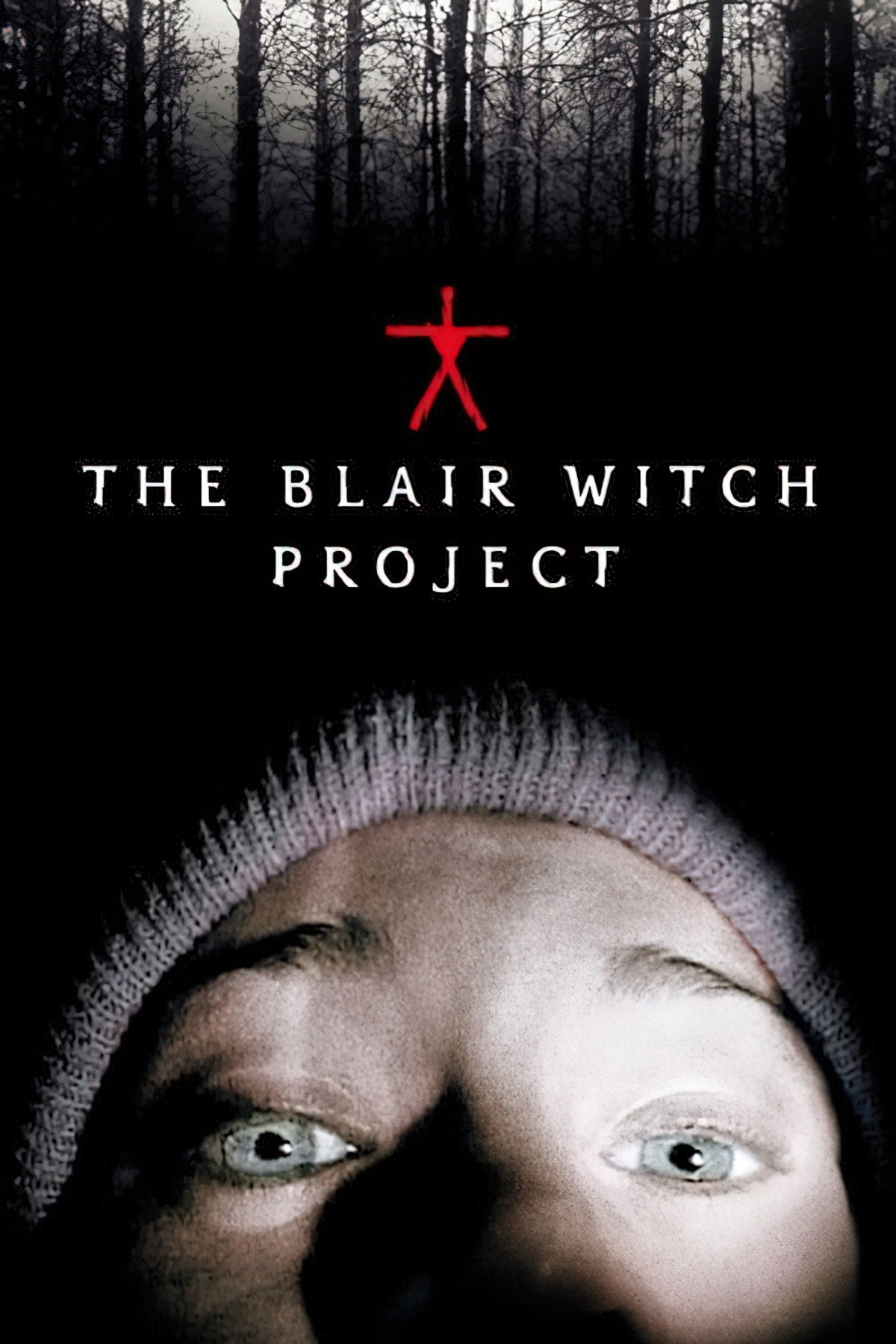

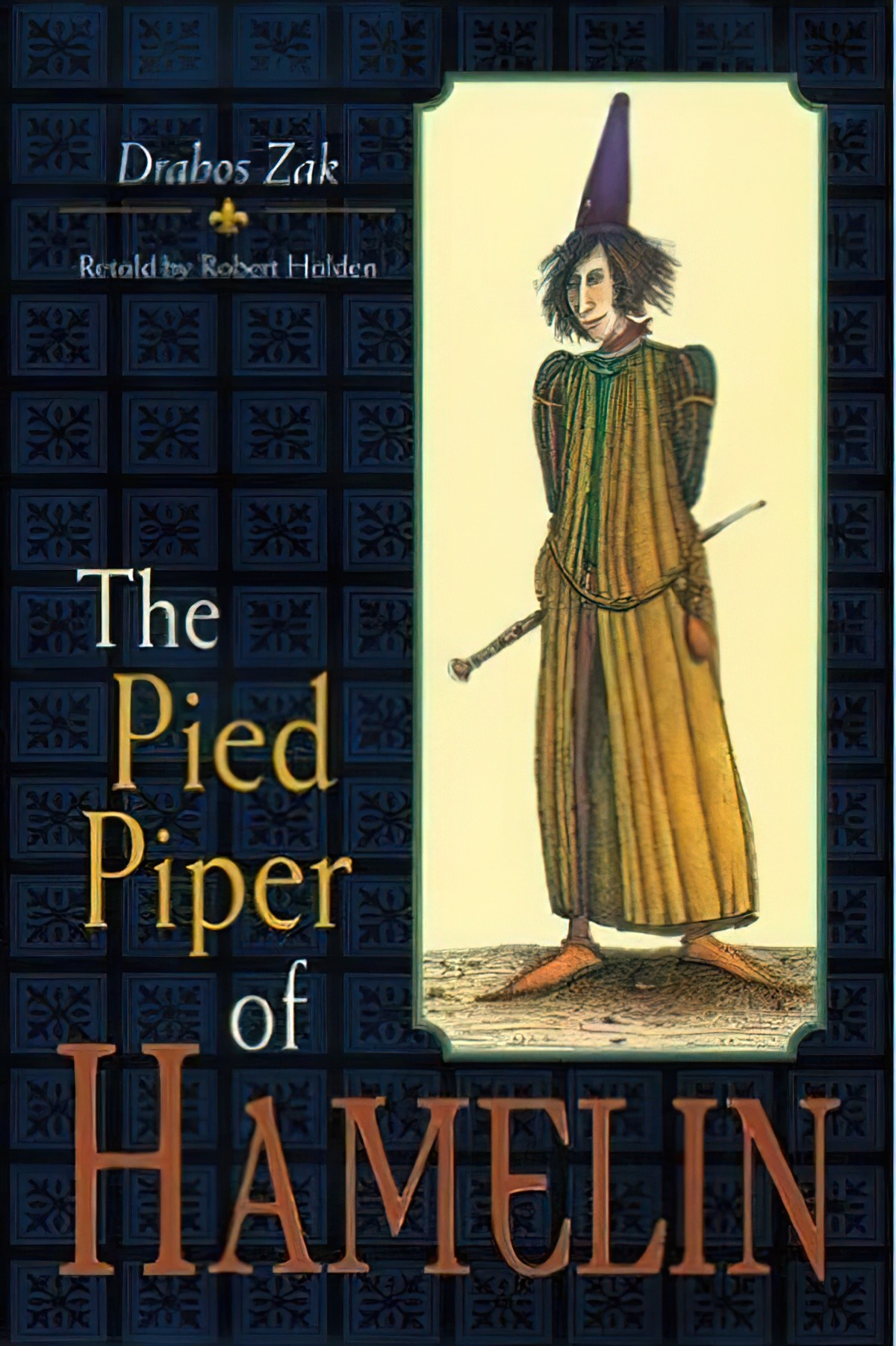

This is usually a full-body shot (a long shot), not only so we can get the full view of this new character but also because the full-body shot is the least inflected with atmosphere. Look at most rom-com movie posters and you’ll see the full bodies of the characters. Compare and contrast to movie posters for psychological horrors and you’ll more likely find cropped images — faces in half light, most of the body off the page, cropped (…and mutilated?)

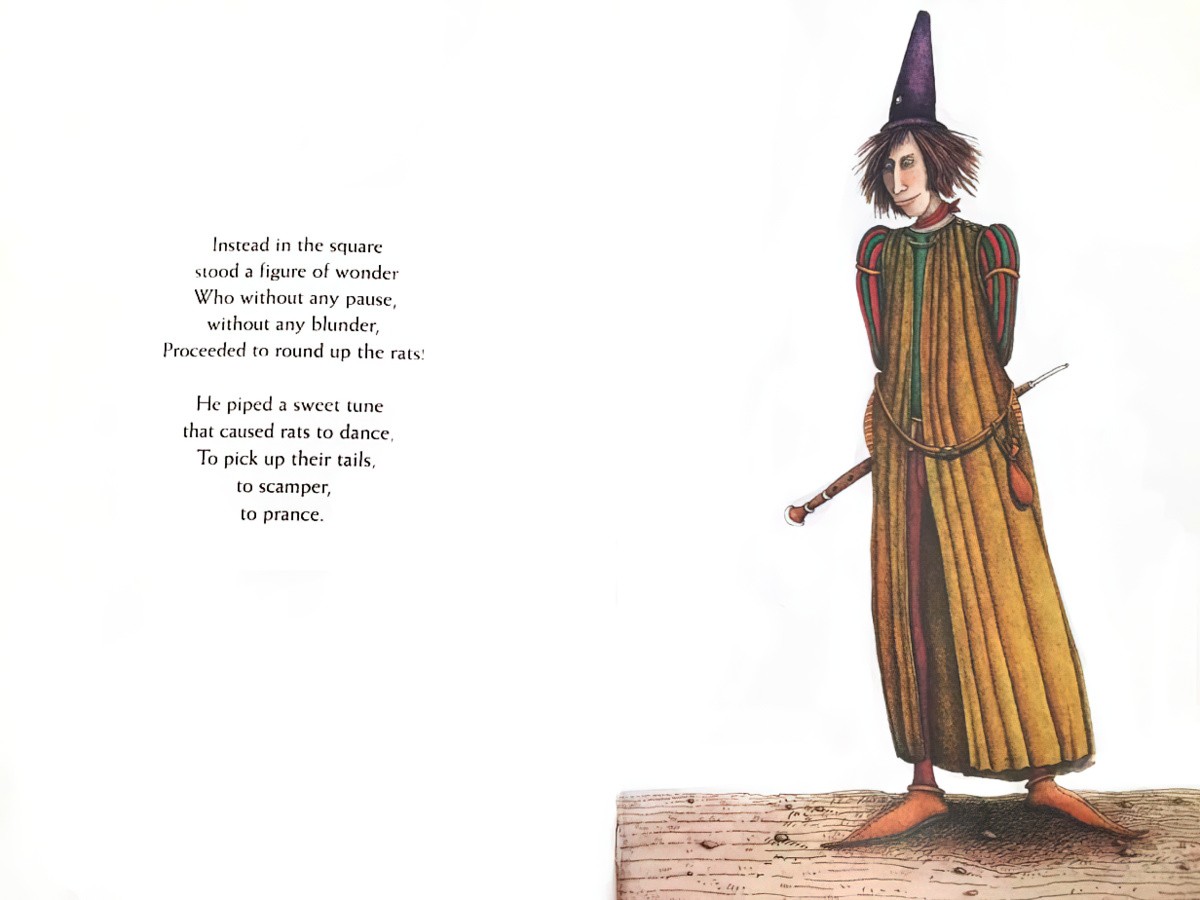

In picture books this static, full-body introduction scene doesn’t necessarily happen on page one. It happens whenever a new, significant character is introduced, and serves to slow the action down.

In The Pied Piper of Hamelin, illustrated by Drahos Zak — an even darker version than your usual fare — we see the Pied Piper posing for us as he is introduced. This is the same ‘posed’ image used on the cover. I haven’t yet seen a Pied Piper done in psychological-thriller-movie-poster style, but surely one exists, as it would be even more creepy.

In The Sailor Dog, illustrated by Garth Williams, a full-bodied, photographic image of our main character does not introduce the character at all. In fact, Sailor Dog (Scuppers) has been through his adventure, survived his Battle at sea and now he’s posing for us after buying new clothes. Here, the posed image performs a different function altogether — Scuppers is a changed ‘man’. He now deserves the suit of a professional sailor.

ON THE LAST PAGE

Finally, of course, in picture books that take place over the course of a day, the main character ends up in bed. Since the norm is to read to children before bed, the very aim of reading picture books to children at all is often (unfortunately) to put them to sleep, so in this case the child is a model for the child, who is also supposed to calm down and settle in for the night.

THE WRITTEN EQUIVALENT OF A STILL IMAGE

There is nothing harder than the creation of fictional character. I can tell it from the number of apprentice novels I read that begin with descriptions of photographs. You know the style: “My mother is squinting in the fierce sunlight and holding, for some reason, a dead pheasant. She is dressed in old-fashioned lace-up boots, and white gloves. She looks absolutely miserable. My father, however, is in his element, irrepressible as ever, and has on his head that gre]ay velvet trilby from Prague I remember so well from my childhood” The unpracticed novelist cleaves to the static, because it is much easier to describe than the mobile: it is getting these people out of the aspic of arrest and mobilized in a scene that is hard. When I encounter a prolonged ekphrasis* like the parody above, I worry, suspecting that the novelist is clinging to a handrail and is afraid to push out.

How Fiction Works, James Wood

A variation on describing a photograph is to have your character sit in front of a mirror and describe themselves. However, sometimes there are good reasons for using this rather cliched scene.