When you encounter mist in real life, what do you recall? Stephen King’s novella? Frank Darabont’s 2007 adaptation of Stephen King’s novella? The 2017 TV series adaptation of Stephen King’s novella?

You may have even studied “The Mist” in literature class — the tertiary level equivalent of Lord of the Flies. This popular science fiction horror contains plenty for discussion and analysis.

Or maybe you’ve never encountered Stephen King’s Mist story before in your entire life, and you don’t scream to family members, “SOMETHING IN THE MIST TOOK JOHN LEE!” whenever fog descends.

I’ve seen the 2007 film numerous times but only just read the novella. There will inevitably be some conflation of those two slightly different stories below, so I’m going to talk about both without worrying about mixing them up.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF “THE MIST”

Though this is a 1980s story, “The Mist” was first written in 1976. Stephen King was near the beginning of his career, and publishers weren’t keen to publish absolutely everything he came out with, so he had to let this one sit awhile. A version of “The Mist” first appeared in a 1980 anthology of horror stories. Film director Darabont read it first in this anthology around this time, and immediately thought it would make a great film. As these things go, it took another 27 years for the film release.

INSPIRATION

“The Mist” is often compared to Lord of the Flies. Stephen King himself says he was going for something akin to an episode of The Twilight Zone.

King tells two different stories about his inspiration for “The Mist”:

- He was in a supermarket with his son Joe and wondered what would happen if a supernatural story happened in that space. He was looking for hotdog buns when “My muse suddenly shat on my head.” The image of the prehistoric bird came first. He wrote half the story that night, the rest the following week.

- In a nightline interview King said he was blocked after writing The Stand. He was in a supermarket with his wife and saw the whole front of the market was plate glass. He wondered what if giant bugs started to fly into the glass.

The storm also really happened, including the water tornado. No doubt Stephen King was inspired by various things at various times. Even someone as open about his writing process as Stephen King is can’t be expected to keep perfect track of his inspirations.

SETTING OF “THE MIST”

PERIOD — A 1970s or 1980s setting.

Perhaps isochronal (it takes about as long to read the story as it would take to play out in real life). Perhaps the story takes longer to read than the action described within, meaning the pace has been slowed down for us.

DURATION

As I write this, it is a quarter to one in the morning, July the twenty-third. The storm that seemed to signal the beginning of it all was only four days ago.

Is Stephen King mindfully avoiding the Biblical three days?

When David goes into the store the world seems a certain way; by the time he emerges, there’s a new world order. The napkin story may have been written a few days later. He’s writing it all down cathartically, also knowing he’s just witnessed an historic event. He still remembers much specificdetail and every quotation, though my take is that he’s making himself look more composed than he really was. (This is first person, after all.)

LOCATION — Bridgeton, Maine. The film is set in Castle Rock. (In the supermarket Irene Reppler is reading the newspaper “The Castle Rock Times”. “Castle Rock” is a town from the trinity of fictional Maine towns created and widely used in works by Stephen King.)

As a non-American reader I have long struggled a little with King’s work as he is in the habit of using unfamiliar brand names. When a guy rides past on a Yamaha I realise the guy isn’t riding a piano, but if I hadn’t seen the film I wouldn’t know that when David uses the army word ‘Scout’ to describe his family car he’s actually referring to his 1968 Toyota Land Cruiser.

I don’t know what a Delco flashlight looks like (not important); I still don’t know what Pola-Glas is, but it’s capitalised, so it must be a brand name. I guess it’s some kind of plexiglass, and that David’s specificity in this regard speaks to his working man’s background. (Tradies tend to know the specific names of building products.)

You get the picture. Point being, this is a very American story, for this non-American reader. I am constantly reminded of the American-ness of it.

ARENA — The fog creates a firm (okay, nebulous) wall around the arena of this story ie. the distance between David’s home and the Federal Supermarket. Fog is also used this same way in another story (more firmly Gothic), The Others.

This episode of the New Books in Economic and Business History is an interview with New York writer Benjamin Lorr. Benjamin Lorr is the author ofHell-Bent: Obsession, Pain, and the Search for Something Like Transcendence in Competitive Yoga, a book that explores the Bikram Yoga community and movement. His second book, The Secret Life of Groceries: The Dark Miracle of the American Supermarket is “an extraordinary investigation into the human lives at the heart of the American grocery store. The miracle of the supermarket has never been more apparent. Like the doctors and nurses who care for the sick, suddenly the men and women who stock our shelves and operate our warehouses are understood as ‘essential’ workers, providing a quality of life we all too easily take for granted. But the sad truth is that the grocery industry has been failing these workers for decades.

In this page-turning expose, author Benjamin Lorr pulls back the curtain on the highly secretive grocery industry. Combining deep sourcing, immersive reporting, and sharp, often laugh-out-loud prose, Lorr leads a wild investigation, asking what does it take to run a supermarket? How does our food get on the shelves? And who suffers for our increasing demands for convenience and efficiency?”

New Books Network

MANMADE SPACES — David’s home, his neighbours’ houses, the Federal Supermarket, the pharmacy nearby.

The plate glass windows were an inspiration for this horror story, and for good reason. Windows, like doors and chimneys, have long been considered dangerously liminal spaces in a house, the place where baddies can get in.

Wayne Jessup: Yeah, we all heard stuff! Like uh, how they… they thought that there were other dimensions. You know, other… other worlds all around us, and how they wanted to try to make a window, you know, so they can look through and see what’s on the other side.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Mrs. Carmody: Well maybe your window turned out to be a door. Isn’t it?

Wayne Jessup: Not my door! It’s the scientists!

Mrs. Carmody: [sarcastically] Oh, the scientists

Ollie: We gotta discuss how we’re going to stop that thing from getting in here.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Myron: What do you mean getting in? We shut the loading door.

Ollie: Yeah, but the entire front of the store is plate glass.

NATURAL SETTINGS — lake. The monsters have a fully functioning ecosystem of their own, by creatures at one with their environment.

WEATHER — It’s, um, foggy. The fog comes after a storm. How is the fog connected to the storm? Don’t know, don’t care. This is no ordinary ‘mist’. It’s more like pollution.

“Dreams, after all, are insubstantial things, like mist itself.”

There was that thin, acrid, and unnatural smell of the mist.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Mechanical horror with the roller door. Fear of technology. The story opens with David’s next door neighbour swearing at his chainsaw, which won’t start despite being the most expensive model.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT — As applies to many Stephen King stories, there’s a dichotomy between insiders and outsiders. Over the course of the story, the cast divides into Team Carmody and Team David. Team David calls the Carmody crew ‘flat-earthers’.

Although King never tells us the details of where all these monsters came from, he gives us enough ‘hearsay explanation’ to satisfy:

Arrowhead Project? Black Spring the Abominations from cellars of the earth?

“The Mist” by Stephen King

EVANGELICAL WITCH: mrs carmody

Mrs Carmody is an on-the-page witch archetype, but Stephen King lets us work that one out for ourselves before he has one of his characters use the word ‘witch’:

That crazy cunt, Miller had called her. That witch.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Next:

Mrs. Carmody’s lips, moving and moving. Her tongue dancing around her old lady’s snaggle teeth. She did look like a witch. Put her in a pointy black hat and she would be perfect. What was she saying to her two captured birds in their bright summer plumage ?

“The day I need a friend like you, I’ll just have myself a little squat and shit one out.”

“The end of times has come. Not in flames, but in mist.”

Biker: Hey, crazy lady, I believe in God, too. I just don’t think he’s the bloodthirsty asshole you make him out to be.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Mrs. Carmody: Well, you take that up with the Devil when you run into him. You just chat it over at your leisure.

Ollie: Those of you who aren’t local should know that Mrs. Carmody is known in town for being unstable.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Biker: No shit. What was your first clue?

David Drayton: Want another reason to get the hell out of here? I’ll give you the best one: her. Mrs. Carmody. Our very own Jim Jones. I’d like to leave before people start drinking the Kool-Aid.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

THE DELIBERATE DOUBTER/flat earth society: brent norton

David Drayton: Sure there’s no way I can talk you out of this?

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Brent Norton: David, there’s nothing out there. Nothing in the mist.

David Drayton: What if you’re wrong?

Brent Norton: Then, I guess… the joke will be on me afterall.

Ollie: We have to tell them. The people in the market. We have to stop them from going outside.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

David Drayton: They won’t believe us.

Ollie: They have to.

David Drayton: I’m not sure I believe it, and I was here. What we saw was impossible. You know that, don’t you? What do we say? How do we… convince them? Ollie, what the hell were those tentacles even attached to?

Deliberate doubters fall into two categories. Some of them eventually have their minds changed, but only after confronting the most horrible of realities:

after Norm is dragged off into the mist

Jim Grondin: [to David] How was I supposed to know what you meant? You should’ve said what you meant better!

“The Mist” by Stephen King

The second type of deliberate doubter will never confront reality no matter what happens.

PRAGMATIST ADAPTER: LEFT-WING secular AMERICAN

Irene: You’d think educating children would be more of a priority in this country but you’d be wrong. Governments got better things to spend our money on, like corporate hand outs and building bombs.

Irene: [after hurling a can of peas at Mrs. Carmody] Shut up, you miserable buzzard! Stoning people who piss you off is perfectly okay. They do it in the Bible, don’t they? And I got lots of peas!

Irene does not trust the government, complaining that there was insufficient education funding to fix a roof. The 1960s and 70s saw stories which reflected Americans’ fresh mistrust of government.

Helen Simpson creates a portrait of a deliberate doubter in her short story “In-flight Entertainment”. For these characters, the worst that can happen is to have someone force the horror of reality upon them.

PRAGMATIST ADAPTER: THE MISANTHROPIST

Amanda Dunfrey: You don’t have much faith in humanity, do you?

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Dan Miller: Ahhh! None whatsoever.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — Ecoterrorism is a theme of this story. “Go green” was big in the seventies. That’s when audiences started to realise we were messing up our environment. I recently took a close look at a middle grade fantasy novel from my childhood, which likewise uses acrid air to stand-for evil. I’m reminded how the 1980s was all about picking up litter. Meanwhile, councils and politicians were concerned with cleaning up air pollution. In rich countries, this has been largely successful. I’m inclined to think in hindsight that air pollution by-laws have allowed climate change deniers to proliferate. It was easier to feel that sense of doom when the air around you literally stank.

‘Emotional landscape’ also refers to the difference between what is real in the veridical world of the story and how a character perceives it — never exactly as it is. How was David wrong about his world? Turns out his wife was right to be worried. She wasn’t just being a worry-wart after all, that was some weird-ass mist. David keeps doing that really annoying Manly-Man thing whereby he secretly is getting worried but he feels it’s his job to pacify his wife (and son). Men are acculturated into believing their role in a family is to be the stoic guy who carries the emotional burder privately, and this does not end well for many men, and women get utterly sick of it.

I would like to point out that when David has his revelation near the end of “The Mist”, he never does realise he was even doing that. As a result, conservative readers, here for the horripilation, aren’t likely to realise that, either.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE MIST

“The Mist” is only a ‘novella’ by King standards. It’s a novel by normal standards.

The underlying structure: a Robinsonnade mythic tale, meaning characters find themselves marooned somewhere, as if on an island. The adventures take place in this single arena rather than along a mythical road.

At the end of the story we learn that David has been writing this story down on note paper he found at a restaurant (in effect, it’s a ‘napkin story’ even if he’s not literally writing on napkins). I have to look up HoJo, which is short for Howard Johnson’s, a U.S. chain of restaurants and hotels.

In hindsight, this explains the chapter titles, which straight up tell us what’s going to happen by listing the plot points, as if David is jogging his memory. If even Stephen King takes a week to write this novella (and he writes quickly) I can’t imagine it takes the artist main character of this story just two days to write that many pages.

David does go into surprising detail about certain things (e.g. sex fantasies), considering this mode of narration. You might think that in an apocalyptic situation where paper is at a premium, a documenter of history could leave out how they enjoyed looking down his wife’s top and grabbing her buttocks. He might avoid ranking the female market customers in terms of how much his dick stirs to look at them, but nope. That, we must deduce, is in there for verisimilitude: the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

Perhaps we’re to believe that it was only the chapter headings which were written on the napkins soon after events, and the rest was written later.

PARATEXT

Notice how much of the advertising material, for the book, the movie, then the TV series, blends the image of mist with an image of glass. Below, a misty background with fingers clearly pressed against something clear yet solid.

Here, the inverse view of a man with his hands pressed against glass. Additionally, they’ve turned the world outside literally upside down.

Mist is a Gothic motif, probably because hanging out in mist is similar to hanging out in a dark forest. We can’t see predators coming at us. Mist also functions symbolically like a veil, suggesting a thin veneer between the known world and the world which lies just beyond. The housing equivalent of this thin veneer is of course the window, with its relatively fragile plate glass, and the ability to see horror play out before your eyes (or between your fingers).

SHORTCOMING

David Dreyton is the first person viewpoint character. Because this guy is telling the story, we have reassurance at the beginning that he hasn’t died, unless this story has been found after he’s been killed, of course. (Which is entirely possible.)

We get a lot of David’s backstory. King did more of this in his early career. Other writers, like Annie Proulx, still do it. Proulx gives us her characters’ back stories going back several generations to show her characters’ insignificance to the land, and also, I think as a subtle commentary on fatalism: Of course this guy is a typical Wyoming guy. How could he not be, with this history?

King establishes David firmly as a man who belongs to the land. He might be doing this to show how David is just one small cog in a master plot which extends generations before him and for generations after, but I doubt it. King has written David as a hero, not as a cog. Unlike the tourists who naively blunder into disaster, David belongs here. I suspect that’s Stephen King’s reason for talking about David’s grandfather.

Because the Dreyton family has a long history in this part of the world, we are told directly (and shown) that he understands how things work. He knows the weather, for instance. He knows what was once allowed and is no longer (sand beaches on private properties) and the way politics works (unless you’re a developer). He knows what to expect from the characters around him.

As I read David’s wife Stephanie deferring to his native-level, masculine expertise I think, if only we took as much notice of actual Indigenous land knowledge as we do of these white men whose connection goes back a paltry three or four generations.

On the topic of the wife, Stephanie’s infantalisation sticks out like a sore thumb. She has no idea what to do in the face of a storm. She contributes no ideas of her own; she has only questions. If King were to switch the wife’s words with Billy’s, we wouldn’t notice the difference.

King is said to have written the following rounded female characters:

- Annie Wilkes from Misery: When Paul is seriously injured following a car accident, former nurse Annie brings him to her home, where Paul receives treatment and doses of pain medication. Paul realizes that he is a prisoner and is forced to indulge his captor’s whims.

- Jessie Burlingame from Gerald’s Game: about a woman whose husband dies of a heart attack while she is handcuffed to a bed, and, following the subsequent realization that she is trapped with little hope of rescue, begins to let the voices inside her head take over.

- Dolores Claiborne: Dolores Claiborne, an opinionated 65-year-old widow living on the tiny Maine community of Little Tall Island, is suspected of murdering her wealthy, elderly employer, Vera Donovan.

- Rose Daniels from Rose Madder: In 1985, Rosie Daniels’ husband, Norman, beats her while she is four months pregnant, causing her to miscarry.

- Lisey Landon from Lisey’s Story: the widow of a famous and wildly successful novelist, Scott Landon. It has been two years since the death of famous author. Throughout the book Lisey begins to face certain realities about her husband that she had repressed and forgotten.

King can write men. He can write children. He can write elderly women. He can also write rounded women of childbearing age, and has demonstrated this in the five examples listed above.

But the majority of Stephen King’s fictional women are Gothic archetypes. One Gothic archetype is the damsel in distress. That’s Stephanie. The women in the supermarket are also modern outworkings of archetypes from Gothic literature.

In the King world women are wives and mothers, and ideally they are much in need of male protection (if they don’t realize it there is something wrong with them)”

“Cat and Dog: Lewis Teague’s Stephen King Movies,” Robin Wood

Eventually Stephanie expresses concern about the furniture, and turns into a nagging wife whose husband is busy picking up the pieces and who can’t be expected to fix everything at once. These wives are a standard companion piece to heroes like David Dreyton, and also to men who are anti-heroes: Skyler White, Carmella Soprano… How many “nagging wife” scenes can you think of in pilots and opening chapters? Even the comically hapless Basil Fawlty is given a nagging wife in Sybil, who in the pilot episode of Fawlty Towers is busy telling Basil to do two jobs at once, and hurry up about it.

I deduce that men must feel widely put-upon when wives ask them to do things, otherwise we would not see nearly so much of this trope when male storytellers create fictional husbands, aiming for audience sympathy, or rather, ‘himpathy’.

Using a variety of tricks including the slightly naggy (but also sexy) wife scene, Stephen King paints the picture of a competent patriarchal man who will come in useful in an emergency.

Then there’s the hot woman on holiday whose husband gave her a gun because he’s away a lot. The Losers’ Club on podcast episode on “The Mist” describes Amanda as “manic pixie dream supermarket wife”.

Commentators have suggested King has written himself in David Dreyton. King considers himself a salt-of-the-earth guy, but has risen in economic rank to be one of the world’s wealthiest people. David Dreyton is also an artist with connections to Hollywood (though an artist, not a writer) and I can imagine Stephen King felt around this time that he was subject to a bit of tall-poppy syndrome; formerly a fully-fledged part of the community, but freshly alienated because of his fancy-schmancy writing accomplishments.

Little wonder David is the good guy whose napkin scribblings rewrite The Story of David, the Action Hero Husband that men would like to be, and who men imagine women want. (And many women do.)

MORAL SHORTCOMING

Does David have a moral shortcoming? This will depend on the audience assessement of him. I can’t stand the guy, personally. Your wife might be dead at home. Meanwhile, after criticising the neighbour for doing this to ‘your’ wife, you’re undressing pretty young women at the market with your eyes. You do dumb stuff like dashing out to the pharmacy because an attractive woman is present.

I don’t believe for a second that David has been written to have a moral shortcoming. If men exist to protect women-and-children (mindfully written as a single concept) then I believe that reflects how conservative audiences think that’s how things are and that’s how things should always be, especially in times of disaster. Popular work always skews conservative, which makes Stephen King the writer an interesting case, seeing as how his politics is in some ways left-wing.

DAVID’S PSYCHOLOGY

I will avoid calling this a shortcoming because David’s fear is in fact a strength. King does a good job of conveying to the audience how scared David is in the face of this cosmic horror.

However, there are parts of society who do consider displays of fear a genuine shortcoming. We have recently started to put a name to this subsection of men: toxic masculinity. (I prefer “toxic forms of masculinity“.)

Is King writing a story about toxic masculinity? I believe the scene in the storeroom is all about that. We could also say the storeroom is a microcosm of warring nations, each with a strongman at the helm, sending the young men in to fight, not directly, no. All you have to do is convince young men that they’d be girls or children if they didn’t put on a brave front, then you can make them do anything you like.

Where does David come out in the masculine strongman wrestle for power? It is the existence of Billy who seems to bring out a softer side of him, where he feels fear internally but by supressing it for the sake of the more vulnerable, he is able to act calmly and rationally, using the facts available. This is the form of masculinity Stephen King rewards. He does not reward the type of masculinity which ends up killing the young man.

I’m sure theses have been written about the specific masculinity of Stephen King stories. Oh look, they have.

- Stephen King’s Phallus; or The Postmodern Gothic by Steven Bruhm (1996)

- Stephen King’s Bookish Boys: (Re)Imagining the Masculine by Kate Sullivan (1999-2000)

- Masculinity As An Open Wound In Stephen King’s Fiction by Diego Moraes Malachias Silva Santos (2018)

IS OLLIE THE ACTUAL GOOD GUY?

Ollie is killed off in this story, which shouldn’t really surprise us. The friendly voice of reason for the viewpoint character is a dangerous guy to be in a story. In any case, if King wanted to keep this first person, Ollie wasn’t around to tell this story.

Is Ollie supposed to be gay or asexual? David tells us two things: That Ollie is “Afraid of girls,” and that he also wears a ring.

Ollie is the one version of morally good, though it’s up to the reader to decide whether killing Mrs Carmody was a morally upright and necessary piece of vigilante justice.

This is a story published in homophobic times, so Ollie is not going to be on-the-page LGBTQIA+. But what of those details? Is it telling detail? David tells us a bunch of things you might expect a man fearing for his survival might leave out. I’m guessing King is telling us something here.

Does this ‘telling detail’ function to elevate Ollie somehow above the carnal desire David feels to protect a wife, and in her absence, to find a stand-in woman he can protect like a wife? What’s the deal there? Is Ollie a Jesus figure?

DESIRE

This is a melodramatic plot, which means the main characters are reacting to some outside force which threatens to disrupt their home and family. The characters desire a return to normality.

OPPONENT

THE NEIGHBOUR YOU CAN’T ACTUALLY TRUST: NORTON

Gothic stories are typically set in a large castle or estate set in the wilderness, far away from neighbours or cities. Why far away from neighbours? Because we assume that were neighbours nearby, they would be there to help us out.

We’re supposed to be able to trust our neighbours, and we like to think we could if push came to shove. But can we, really?

Brenton Norton is initially presented as a typical neighbour opponent. Even his rhyming name conveys comedy alongside subsequent comedy greats such as Dwight Schrute. (Henny Penny, Foxy Loxy et al are also comically stupid.)

Stephen King tricks us a little by suggesting a redemption arc is about to happen between Norton and David, and the two neighbours will each complement each other in their strengths and weaknesses.

But Stephen King avoids this hackneyed redemption arc, even though there’s a long, successful history of redemption arcs in American narrative.

THE HUMAN VILLAIN: MRS CARMODY

Stephen King has made this witch specific by marrying witch tropes with evangelical proselytisers. King uses a very similar character for Carrie’s mother.

Taxidermy is considered one of the creepiest professions. (This stuff has been researched.) Whenever a storyteller introduces a witch, there should be some question in the reader’s mind: Is she a good witch or a bad witch?

Like a classic horror monster, Mrs Carmody is robotic in her ability to go on and on through battle. King uses the word ‘tireless’ to describe the way she filibusters:

She was tireless, apparently. And she was indeed discussing human sacrifice again, only now no one was telling her to shut up. Some of the people who had told her to shut up yesterday were either with her today or at least willing to listen-and the others were outnumbered.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

I note with interest that Mrs Carmody’s “pantsuit” is mentioned a number of times. You know who else had her pantsuits mentioned over and over ad infinitum? Hillary Clinton. You know who else wears pant suits? Every single male politician ever. But when women’s pant suits are mentioned, there is an emphasis on the fact that they are not wearing women’s suits, ya know, with skirts. In turn, the emphasis is on the manliness of the pants, which in light of the fact that Stephen King writes monstrous women by deducting the dominant culture’s notion of femininity le propre, had a bit of an uncomfortable edge to it, especially given as how Stephen King is a pretty loud Democratic on social media and all.

Monstrous Women in Comics

In their collection Monstrous Women in Comics (University Press of Mississippi, 2020), Samantha Langsdale and Elizabeth Rae Coody put together a critical volume on the ways women are made monstrous in popular culture. This edited volume examines the coding of woman as monstrous and how the monster as dangerously evocative of women/femininity/the female is exacerbated by the intersection of gender with sexuality, race, nationality, and disability. The five sections of this book look at the cultural context surrounding varied monstrous voices: embodiment, maternity, childhood, power, and performance. This volume probes into the patriarchal contexts wherein men are assumed to be representative of the normative, universal subject, such that women frequently become monsters.

New Books Network

THE MINOTAUR OPPONENT: THE “TENTACLES”

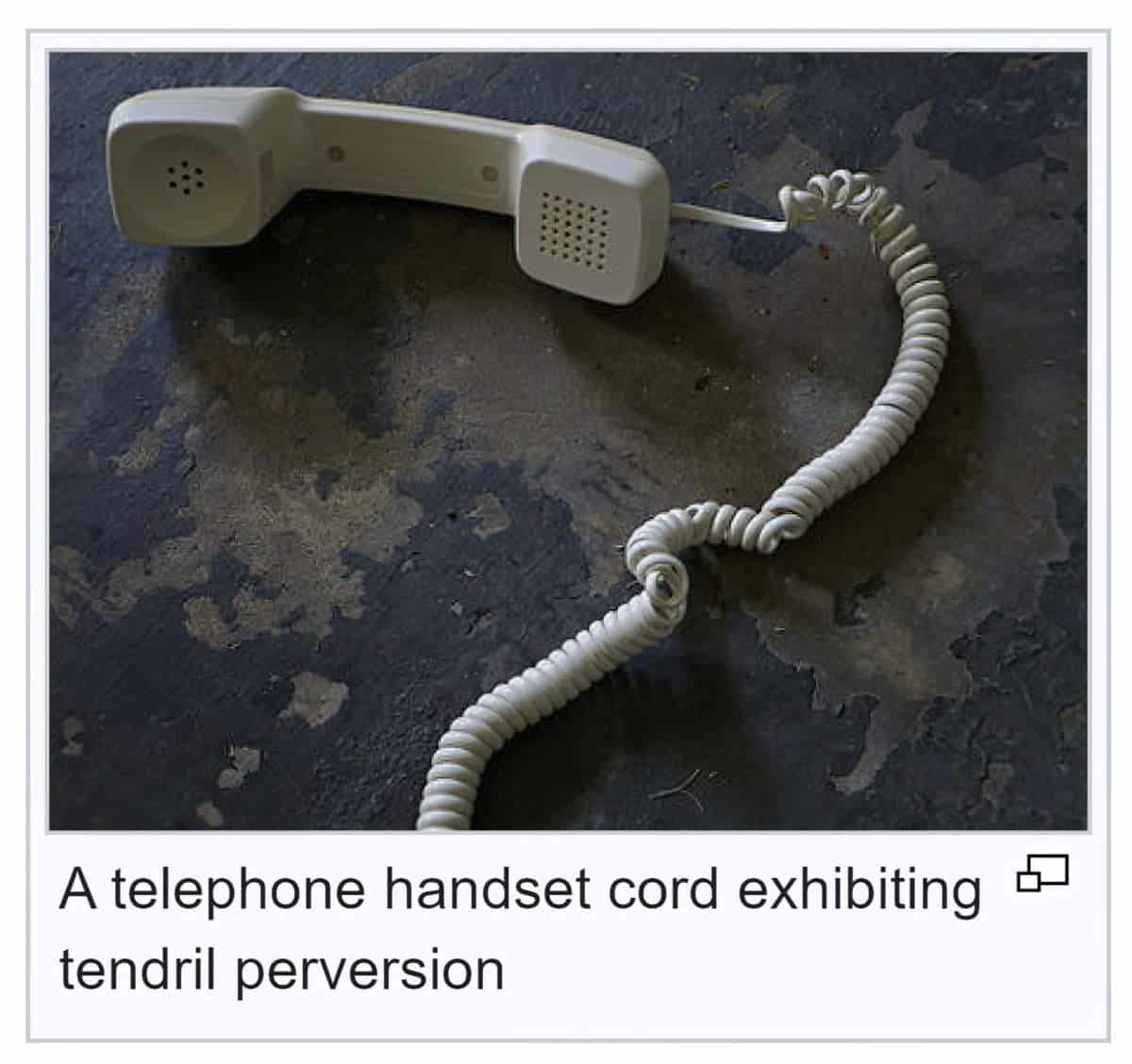

There’s a movement on social media to reclaim the correct, scientific meaning of ‘tentacles’ but Stephen King can be blamed entirely for the language shift which now means ‘any kind of appendage on a cephalopod’. If Apple can repurpose iPad, and make us NOT think of sanitary pad, then Stephen King, horror King, can repurpose ‘tentacle’.

Note that Stephen King does not limit himself to one type of scary creature coming out of the mist. After the “tentacle” scene in the store room with the roller door he understands the readers don’t need another action murder sequence with tentacles, so he has also created big spider type thingos, and it doesn’t bother Stephen King one whit that it’s a huge unlikelihood that these vastly different types of creature are all coming out of the same misty stuff. Readers don’t care about the etiology of these monsters. More monsters, better horror.

PLAN

Staying in the supermarket is not an option for David and Team David. Mrs Carmody is getting more and more wild, and recruiting more and more desperate people into her Doomsday cult. David is therefore forced to vacate the supermarket to save his young son, because Mrs Carmody the Human Monster wants to use the young boy as a sacrifice.

This works because it comes from real human history, in which various peoples around the world have at times used humans (and children) as sacrifice to appease their gods.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The first trip out is to the Bridgton Pharmacy, just 20 feet from the Federal Supermarket where they’re holed up. That doesn’t go so well. A number of characters are plucked off. The reader is introduced to a new kind of creature — spiders with too many legs to be spiders, who catch humans in their web.

VOCABULARY

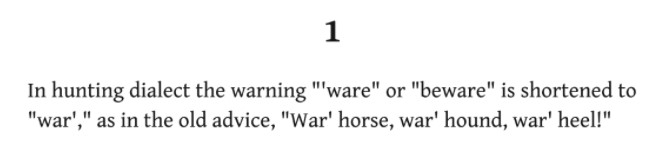

One question I had: Why does Mrs Reppler shout ‘Ware!’

Mrs. Reppler had turned around. “Ware!” she screamed in her rusty voice. “Ware behind

you! “

She seems to be saying ‘ware’ as a shortening of ‘Beware!’ or ‘Look out!”

In Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 26, August, 1880 I found my answer.

This speaks to Stephen King’s amazing ability to derive words from the most eclectic of sources. In On Writing he advises other writers to avoid using words that aren’t already in their active vocabularies. Which is good advice, so long as writers are also following his other advice: Read widely enough and often enough to develop an interesting active vocabulary.

King has made us of old hunting dialect to emphasise the elderly frailty of Mrs Reppler and also to turn her into a hunter.

During the final Battle, as the four survivors dash to David’s car, King decides to use Amanda as the Screaming Woman. But it would be a bit too on-the-nose misogynistic to have David telling her to shut the hell up, so he gets Cool Old Lady Mrs Reppler to do it for ‘us’:

Amanda screamed ceaselessly, like a firebell.

“Woman, shut your head,” Mrs. Reppler told her.

ANAGNORISIS

This story won’t feel finished unless David realises something or has some kind of catharsis. The catharsis isn’t the main point of a story like this. The point of a Stephen King horror is the enjoyment of horripilation. If you’re after a completely new way of seeing the world, lyrical short stories are your best bet. Nope, David’s epiphany is that family is important, and no one is more important than his little son Billy:

It is Billy I have to think about now. Billy, I tell myself. Big Bill, Big Bill … I should write it maybe a hundred times on this sheet of paper, like a child condemned to write I will not throw spitballs in school as the sunny three-o’clock stillness spills through the windows and the teacher corrects homework papers at her desk and the only sound is her pen, while somewhere, far away, kids pick up teams for scratch baseball.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

Finally, King lets the guy have a cry:

Anyway, at last I did the only thing I could do. I reversed the Scout carefully back to Kansas Road. Then I cried.

“The Mist” by Stephen King

(Men don’t cry enough in fiction.)

NEW SITUATION

There are four classic endings to a story:

- purely positive

- purely tragic [Breaking Bad]

- positive with irony where the character gets what s/he wants but pays a big price [a.k.a. pyrrhic victories]

- tragic with irony where the main character loses everything but they learn something [Big Love]

If you’ve seen the 2007 movie and also read the novella, you will know by now that the endings are different. The movie gives us a final gut-punch, utilised in a number of stories but which always seems to work no matter how many times we see it: One character kills another when they didn’t even have to. See it also in one of the Buster Scruggs stories (2018). These guys come out alive, but without the ones they love the most. The ultimate pyrrhic victory.

This trope can also be found in urban legend. From Australia we have the urban legend of “The Faithful Hound”:

A young couple who had recently become parents for the first time suddenly found that they had to rush out to attend to an emergency. Not having had time to arrange a babysitter, they put their trust in the faithful family dog to look after their young baby. Leaving the baby in his cot, they locked the dog in the house and dashed off.

On returning home, they rushed in to check on the baby. When they turned on the bedroom light, they were greeted by the sight of their faithful hound slavering over blood and flesh on the carpet. Their baby was nowhere to be found. Obviously, the faithful hound had killed the child! Stricken with grief and horror, the young parents immediately killed the dog by slashing its throat.

Just as the execution was completed, the parents heard a whimpering sound. Desperately scouring the room, they traced the sound to beneath the baby’s cot. There was the baby, alive and well, lying beside the mutilated body of a German Shepherd.

Bewildered and relieved, the parents hugged and kissed their child as the police burst in. ‘Have you seen a German shepherd round here?’ asked the police sergeant. ‘We’re tracking down a mad one that’s taken to attacking children.

The couple were horrified; their faithful hound that they had just killed had torn the German shepherd to pieces to protect the baby.

Great Australian Urban Myths by Graham Seal (1995)

King forewarns us in the novella (with the reference to Hitchcock) that he won’t be tidying this story up nicely for us:

Both the novella and movie versions of The Mist are excellent, but they radically differ when it comes to the ending. While the film goes in a decidedly dark direction, King’s novella is much more ambiguous. In fact, the author actually leaves his readers with some hope that things will work out for David and his crew. Team David escapes the super market, but instead of committing mass suicide, David turns on the radio and thinks he hears a voice say the word “Hartford.” Encouraged, he believes Hartford, Connecticut, might be a safe zone, and he heads in that direction.

The novella ends with David narrating these final lines: “I’m going to bed now. But first I’m going to kiss my son and whisper two words in his ear… Two words that sound a bit alike. One of them is Hartford. The other is hope.” And that’s where the book ends, hinting that maybe Team David is going to be okay. Obviously, Darabont decided to traumatize moviegoers, thanks to the political landscape at the time, but Stephen King was totally okay with the new ending. When Darabont asked for King’s opinion on the nihilistic finale, the author gave him two thumbs up. King even famously declared that “anybody who reveals the last 5 minutes of this film should be hung from their neck until dead.” We really hope he doesn’t read this list.

The Ending Of The Mist Finally Explained, The Looper

Audience reactions to open endings will be mixed. Rusted on readers of genre fiction can often have little patience for storytellers who don’t tidy up the plot before they shuffle off. In the novella, Stephen King is going for an ending that is more poetic, more true to the tradition of the classic short story, in which a minor character finds closure that symbolizes the next step for everyone.

Sometimes the point is that there is no resolution — because life can be like that. These stories are ‘the question minus the answer‘. Literary stories make their point via symbolism.

In the novella, has Stephen King given us enough ‘symbolism’ for us to extrapolate our own endings?

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

As I do the mental exercise of, “What happens to David next?” it strikes me that I don’t care. David is more like the main character of cosmic horror than a sympathetic hero I’m meant to root for. He really is the American Every Man, the rugged, manly Family Man, which means he could also be Any Man at all.

He probably lasted about as long as his next tank of gas. If anyone survived, it’s probably Mrs Reppler. She’s clearly got a secret hunting background, and has seen enough of life to remain calm(-ish) under the most trying of circumstances.

That said, if this is a movie, Amanda would make an adequate Final Girl, coming in useful for the scream layer of soundtrack.

RESONANCE

Stephen King writes widely loved commercial horror by creating a perfectly blended pastiche. This one draws heavily from the Lovecraftian tradition. King even puts this right on the page: His main character realises he’s in a Lovecraftian situation. It took decades for the film adaptation to be made, and another decade exactly for the TV series to appear. The movie is more highly rated than the TV series, which transferred the setting to a mall, and made more use of horrific CGI. Whereas the film scores 7.1 on IMDb, the series scores a don’t-even-bother 5.4. This is no doubt due to a number of reasons, but suggests overall that a good story is not necessarily improved upon lengthening.♦

SEE ALSO

Dans la brume tells the story of a small Parisian family who must fight for their survival when a huge cloud of suffocating mist suddenly invades the city. With the girl suffering from an incurable disease forcing her to live in a glass bubble, her parents will have to find a way to get her out of there as the mist continues to rise.

Review – In the Mist, by Daniel Roby, Kinephanos