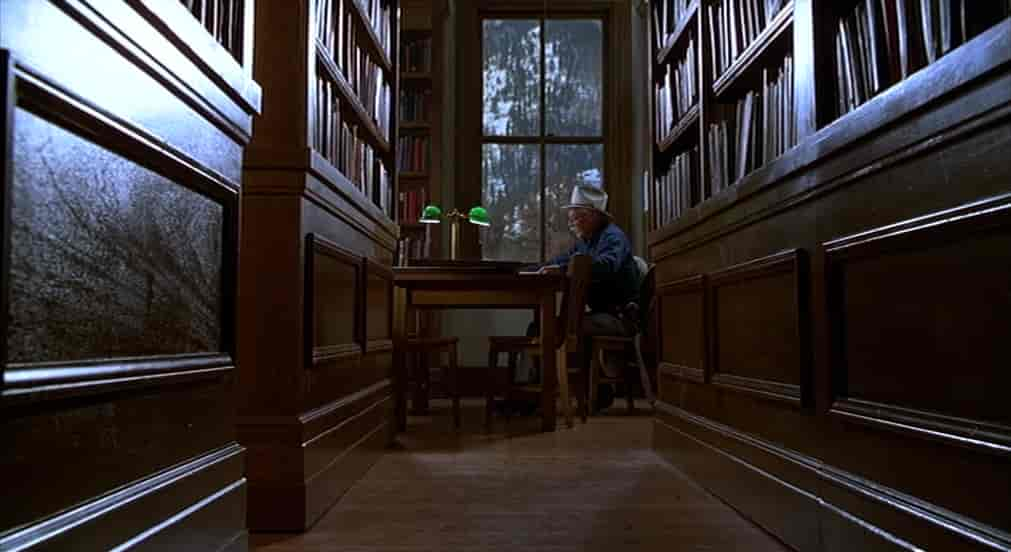

Misery (1990) is one widely considered of the best Stephen King film adaptations. This is a psychological horror which uses the Hitchcockian language of thriller. It’s also a depraved inversion of a love story, with inverted romance tropes.

After a famous author is rescued from a car crash by a fan of his novels, he comes to realize that the care he is receiving is only the beginning of a nightmare of captivity and abuse.

logline of Misery (1990)

WHERE TO LISTEN

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. Misery was broadcast September 2004.

In Misery, the ‘meet cute’ involves a woman rescuing a man from a car crash. A man and a woman, forced to spend time together because of a snow blizzard outside which has cut them off from the rest of the world. This is a rich-man-poor-woman narrative, but not like Pride & Prejudice, Cinderella or Pretty Woman. No, not exactly like that.

In fact, if you’ve had a gutsful of rich boy, poor girl romance, or romance in general, Misery may fit the bill? Who knows, maybe Misery is your new favourite Christmas movie? I mean, there is snow.

WHAT MAKES MISERY WORTH WATCHING?

Running at 1 hour 45 minutes, this film is the perfect length and has the perfect pacing. Editing is tight. Remove a single scene and the story wouldn’t hold.

THE ENDURING THEME OF CELEBRITY

Misery deals with the dark consequences of fame, and the reality that certain professions require that the author sell themselves as well as their product. Authors will tell you this has only become more and more the case since the advent of social media. Authors are now expected to create a persona online and interact with readers, especially if they’re new to publishing and do not yet have a recognisable brand name. Stephen King is himself active on social media, especially Twitter. (How many Annie Wilkes followers does he have?)

But it’s not just authors/actors/singers/artists who create an online persona for themselves. Unless we make an active decision to avoid it, pretty much everyone has an online persona which is effectively a managed version of ourselves for public consumption, and which can affect our livelihoods and love lives as potential employers and partners ‘get to know us’ online.

Misery was written in pre-WWW times, but the ‘inherent danger of fame’ aspect continues to resonate.

Every so often, a literary character comes along who defies all attempts at

Gender Role Reversal In Misery, Chapter 2, “Sometimes Being A Bitch Is All A Woman Has”: Stephen King, Gothic Stereotypes and the Representation of Women, Kimberley S. Beal (2012)

categorization. Annie Wilkes is one such character. In her, King has created a character of undeniable monstrosity, yet one that attempts to fulfil, and is in many ways successful at, the domestic test.

I’M YOUR NUMBER ONE FAN!

Annie Wilkes is the uber-Number One Fan, but they make great characters in either horror or comedy. Comedy and horror are surprisingly similar. Notably, the villain who just won’t quit. Be it the robotic psychopath who just keeps going and going even though you’ve shot it up twenty times, or the Number One Fan who pops up in the weirdest places, this is one-and-the-same archetype, different genres.

Syndrome, real name Buddy Pine, is the main antagonist of the Disney Pixar 2004 animated film The Incredibles. He was a supervillain and mad scientist who used to be Mr. Incredible’s biggest fan until Mr. Incredible refused to let Syndrome be his sidekick when he was young.

Stephen King has said that Annie Wilkes is his favourite creation. He especially enjoyed Kathy Bates’ depiction of Annie in the 1990 film adaptation of his 1987 novel, and subsequently requested Bates to play two other of his characters:

- Dolores Claiborne (1995), a psychological thriller drama of the same name

- Rae Flowers in The Stand, which was previously a male character called Ray, with gender changed specifically for Bates.

Kathy Bates’ performance of Annie Wilkes is especially impressive knowing that she came directly from a theatre background. Theatre acting, while still acting, is a vastly different job from film acting. Bates needed to rehearse scenes. In contrast, James Caan (who played Paul Sheldon) hated rehearsing scenes. This created a touch of real-life opposition between the two actors, which surely manifests in the final product.

These days, Stephen King seems to have made peace with the reality that film adaptations of his novels will not always live up to the stories of his books, and goes on record as saying that a film and a book can exist side by side as separate things. But he clearly feels a little more strongly than that, because he would only allow a Misery adaptation if Rob Reiner was involved at the executive level. This despite Rob Reiner’s total lack of experience in the thriller and horror genres. Why Rob Reiner? Because Reiner had done such a great job of Stand By Me, the first movie person to really impress King.

(Note that Rob Reiner named his production company Castle Rock, after the fictional area in Maine known as Stephen King Country.)

MISERY AND HITCHCOCK

Rob Reiner famously prepared for the job as director of Misery by watching the complete oeuvre of Alfred Hitchcock. This equipped him with ‘the language of thriller’.

Sure enough, Hitchcockian technique can be seen in the film.

The claustrophobic set

The crew literally cheered when, after six weeks of shooting in the same small room, they were finally moved out… and into the hallway (not much better, surely!). The audience experience of watching Misery: We’re right there with John Sheldon, unable to escape. Hitchcock, too, captures this experience in films such as Rear Window. (The claustrophobic set of Misery is reminiscent of a stage play which has been adapted for film; in reality this story went from novel to film to stage play.)

Film-makers have used wide lenses. Wide angle lenses offer a wide field of view, so you may consider this the wrong choice to convey claustrophobia. With this massive lens, the tiny bedroom feels cavernous, but it changes the audience perception of size. When Paul is near the camera, he now seems huge. This is too subtle to notice unless you’re on the lookout, but Eye of the Duck podcast alerted me to the technique: Wide angle lenses are utilised whenever Annie is in one of her darker moods. She seems massive. Kathy Bates herself is five foot four. In contrast, James Caan was five foot eleven. Cameras can do a lot with size.

The Art of Pure Cinema: Hitchcock and His Imitators

The Art of Pure Cinema: Hitchcock and His Imitators (Oxford University Press) is the first book-length study to examine the historical foundations and stylistic mechanics of pure cinema.

Author Bruce Isaacs, Associate Professor of Film Studies and Director of the Film Studies Program at the University of Sydney, explores the potential of a philosophical and artistic approach most explicitly demonstrated by Hitchcock in his later films, beginning with Hitchcock’s contact with the European avant-garde film movement in the mid-1920s.

Tracing the evolution of a philosophy of pure cinema across Hitchcock’s most experimental works – Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds, Marnie, and Frenzy – Isaacs rereads these works in a new and vital context.

In addition to this historical account, the book presents the first examination of pure cinema as an integrated stylistics of mise en scène, montage, and sound design. The films of so-called Hitchcockian imitators like Mario Bava, Dario Argento, and Brian De Palma are also examined in light of a provocative claim: that the art of pure cinema is only fully realized after Hitchcock.

New Books Network

SET DESIGN

Making things more terrifying, this house will feel familiar to many Americans, who may know someone who lives in a house just like this, with those kitchen implements, that wallpaper.

THE MEANING BEHIND THE CERAMIC PENGUIN

When Paul escapes the bedroom and manages to explore the house, he knocks over a penguin. He rescues it from smashing, but doesn’t imagine Annie will know he tampered with it: This penguin always faces ‘due south’.

Annie: Paul, my little ceramic penguin in the study always faces due south.

Misery film script

Could this be symbolic in any way? Of course, Annie is the exaggerated extension of the houseproud relative who doesn’t like children in the house because children muck everything up, causing her more housework. Also, Annie surrounds herself with animal knick-knacks because she herself feels affinity to pigs. But what about the symbolism of ‘south’? Does it mean anything that a penguin faces south? Well, penguins live in the south (polar bears in the north) but let’s not stop there.

Okay, so here’s the general rule: whether it’s Italy or Greece or Africa or Malaysia or Vietnam, when writers send characters south, it’s so they can run amok. The effects can be tragic or comic, but they generally follow the same pattern. We might add, if we’re being generous, that they run amok because they are having direct, raw encounters with the subconscious.

Thomas C. Foster, How To Read Literature Like A Professor

Which creatures, in history, ran amok? Pigs. See:

Jørgensen, Dolly. “Running Amuck? Urban Swine Management in Late Medieval England.” Agricultural History, vol. 87, no. 4, 2013, pp. 429–51. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.3098/ah.2013.87.4.429.

Z41. The old woman and her pig. Type 2020.

in Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966 (604 of 606)

And for more on the symbolism of cardinal direction, see this post.

THE BASEMENT

If you’re American, perhaps you can even imagine the smell of Annie’s house. For me as an Australian, this feels very much like a horror movie house. Houses don’t typically have basements here.

Speaking of basements, Silence of the Lambs audiences will recognise the similarities between the tense basement scenes in both movies. (Why reinvent the wheel, right?)

MONTAGE SHOTS

This is a common film-making technique now, and one Hitchcock utilised to great effect. These montages comprised a series of carefully curated close-ups. Framing allowed him to hide parts of a scene from viewers. We might see a face, next an arm, then a weapon. Montages allow the film-maker to dish out information in perfectly apportioned bites, and also to exact control over timing.

INSERT SHOTS

An insert shot “any shot that’s sole purpose is to focus the viewer’s attention to a specific detail within a scene.”

As part of Misery’s claustrophobic setting, there’s much emphasis on (closed) doors. Annie’s house has so many doors. So many doors and none of them offer escape.

The camera zooms in on the door handles, and the audience either sees it turn or doesn’t see it turn. In these moments, we see the world through Paul Sheldon’s eyes.

THE ROAMING CAMERA

Hitchcock’s camera would frequently rove around a room, as if it were a live beast looking for something suspicious and telling.

POV SHOTS

The insert shot is usually from the point of view of the sympathetic character, but Hitchcock pioneered a method of film-making which really put audiences in the shoes of the designated main character. This was done in various ways, not just with insert shots. The Hitchcockian camera was basically a voyeur.

Hitchcock would regularly switch POV between the object and subject (empathetic character vs their opponent). This puts the audience in an uncomfortable omniscient position which he utilised to build suspense. (The audience knows what’s about to happen because we’ve seen the gun under the table.) Discomfort comes from knowing what’s about to happen but being powerless to stop it.

THE OFF-BEAT LEADING LADY

I prefer to avoid lionizing Hitchcock, who was the Weinstein of his day. He had a type when it came to women: blonde, obviously. Also, Hitchcock combined sexuality with a touch of fetishism. Not enough to attract the censors’ censure, but still it’s noticeable.

Kathy Bates isn’t exactly the blonde preferred by the likes of Hitchcock, but is she really an inversion? Not exactly. The S and M stuff is all right there. And that fight scene at the end between Annie and Paul? That was Rob Reiner deliberately merging a fight scene and a love-making scene.

The difference between these leading ladies and who came before: They may be evil and tricky, but at least they had agency. They knew what they wanted, so they went ahead and did it. This appealed to women as well as to men.

A ‘HOBBLED’ MALE LEAD

In Misery the male lead is literally hobbled, but Hitchcock’s men were also hobbled, sometimes with a physical disability, sometimes psychologically. These men were easily bewitched by the blonde bombshell leading lady, typical of the film noir tradition.

This is the Hitchcockian language of thriller.

SIMPLE PLOTS

Misery has a very simple plot. The same was true for Hitchcock’s films. The plot of Psycho is about as complex (simple) as the plot of Misery. Those stories are similar in a number of ways, which is why a Hitchcockian approach suited the adaptation so well:

- A road trip out of the safety of the city with a goal in mind

- Veering off the path

- Finding ‘refuge’ in an old, American-style home

- Your host is a psychopath who is out to kill you

MACGUFFIN

The Macguffin is one of the most famous Hitchcockian storytelling techniques. A Macguffin sets off the story, but the audience is supposed to forget about it. (In Psycho it’s Marion Crane’s theft of the money. We forget all about the money, and never learn what happened to it.)

Does Misery feature a Macguffin? Not exactly. But it does feature that pesky big coincidence near the beginning, when Annie just so happens to ‘rescue’ her idol. We are not supposed to wonder, while watching events play out, whether Annie set the whole thing up. This works, too, because for all we know, Annie is a perfectly nice lady and surely this guy has many fans.

Audiences will tend to wonder about that coincidence afterwards. This creates another famous Hitchcockian phenomenon known as the Refrigerator Moment (when you go get a beer from the fridge after watching and think, “Hang on…”)

In this way, MacGuffins and Refrigerator Moments go hand-in-hand.

See also: Episode 60 of the Then Again Podcast: Alfred Hitchcock’s Art of Suspense. “Special guest and movie buff Matt House discusses the techniques and methodology of Alfred Hitchcock’s thrillers.”

WHERE IS MISERY SET AND FILMED?

Many of King’s stories are set in Maine, but Misery is set in snowy Colorado.

The film adaptation was filmed in Nevada (Genoa and Reno), with sets in Los Angeles.

The parts with Paul Sheldon’s publisher were filmed in New York City (The Seagram Building). The restaurant scene at the end happens in New York but was shot in California at an eatery called Millennium Biltmore Hotel. Pretty much every nook and cranny of this historical hotel has appeared in movies. For Misery, the South Galleria was dressed to look like an upscale NYC restaurant.

IS ANNIE WILKES A PSYCHOPATH?

I’m interested in fictional portrayals of personality disorders, so was interested to learn about the featurette on the Kino Lorber 4k DVD release of Misery in which a psychologist diagnoses Annie Wilkes. Unlike, say, Hannibal Lecter of Silence of the Lambs (a character who would not exist in real life), Annie attracts specific diagnoses:

- psychopathy — check! Note that, these days, psychopathy and grandiose narcissism are considered the same disorder. (‘Vulnerable’ narcissists are another type who present differently but who suffer from the same underlying issue: chronic lack of self worth.) Annie doesn’t see Paul as a person, but only as a tool to write her fantasy stories. She’s not one bit interested in hearing about his daughter when Paul tries to humanise himself to his captor. This dehumanisation may be considered an inverted romance beat: Before we really know our romantic partner we are inclined to imbue them with all sorts of wonderful characteristics which aren’t really there. (Such is the liminal phase of love.) Later, when we learn the nature of the real person in front of us, we either fall out of love or further into it, as has happened to the McCains in this story. (The police officer couple.)

- bipolar personality disorder with sadomasochistic tendencies — “tendencies”? the hobbling scene!

- delusions of grandeur — Annie appears at time to be humble. Paul tries to appease her by saying perhaps she could come up with a title for his new book. “Oh, like I could do that,” she says, dismissing her own abilities. Later, “Oh, it’s ridiculous, who am I to make a criticism to someone like you?” Eventually her delusions are revealed, however. Annie tells the sheriff who comes knocking: “God told me, since I was his number-one fan, that I should make up new stories as if I was Paul Sheldon.”

- a false sense of morality — Annie is fine with enslaving and maiming a man, murdering babies and possibly feeding them to her pig; not fine with workaday colloquial swearing.

ANNIE AND AUDIENCE EMPATHY

Note that psychopaths are impaired in their ability to feel affective empathy. Yet they frequently have excellent cognitive empathy, and know how to make others do what they want. The story itself plays with the audience’s affective empathy. At times we almost feel for Annie and want to side with her when she’s at her most charming.

It helps that Annie Wilkes is a middle-aged woman, a nurse, with (albeit fake) mothering behaviours. We are told as children, If ever you’re lost, look for a woman with children. Statistically, women are less likely to assault you and more likely to look after you.

This advantage of being a woman has its malignant flipsides, namely that it’s an outworking of misogyny, in which women are expected to live their own lives in service to others.

This is also the very reason a female psychopathic killer is even more terrifying than a male equivalent. A motherly figure who also murders babies? The most terrifying monster of all. It is quietly terrifying to have a mother who is childlike, too. A mother cannot provide care if she herself requires mothering. We see the childhood Annie come out when she asks Paul, “Did I do good?”

Basically, we require so much of mothers. Female villains can work so well because when they fall short, we fall apart.

And don’t even think about anybody coming for you, not the doctors, not your agent, not your family–because I never called them. Nobody knows you’re here. And you better hope nothing happens to me because if I die, you die.

Misery 1990

There’s a parasitic symbiosis to the relationship between Annie and Paul. These days many people know the phrase ‘parasocial relationship’, which describes the ‘relationship’ between a fan and a celebrity. I feel this word has only entered everyday lexicon since the proliferation of social media. In the 1980s and 90s I never once heard the term in everyday conversation. However, it has been around since the 1950s, known among psychologists.

(The term parasocial relationship is credited to sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl, who used it in their 1957 article “Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction.” “Gaslighting” is another word which has been around since the 1940s but which has only recently become widely understood.)

Back to Annie, and her tenuously proposed femininity. As children we are lost without a dedicated caregiver, most frequently someone who looks very much like Annie Wilkes. You probably know a woman who looks like Annie Wilkes. Perhaps she’s your mother, your aunt, your neighbour, your schoolteacher. Kathy Bates is the perfect depiction of ordinary white womanhood, and she looked somewhat matronly even as a relatively young woman, as she was here.

HOW OLD WAS KATHY BATES WHEN SHE STARRED IN MISERY?

Kathy Bates was born in 1948, which makes her 41 during the filming of Misery and 42 years old at time of release.

The psychopathic (cannibalistic) mother-figure makes a frequent appearance in classic fairy tale, bowdlerised from mother to step-mother in more recent renditions to remove the absolute horror of having your very own birthmother depositing you in the woods because she can no longer feed you. Stephen King makes much use of this archetype, e.g. Carrie’s mother, Mrs Carmody of “The Mist“… These women are frequently affected by evangelical Christianity and their warped moral code comes from the most horrific parts of The Bible, which can justify any action when read by the wrong person looking for moral back-up.

The other thing about these Nice White Ladies: They are so sure they’re correct, their morality evinces extreme irony. In Annie’s case, she can’t abide taking the Lord’s name in vain, but will happily violate any number of Commandments in service of her own needs. So long as she doesn’t swear, she can do as she pleases.

Of course, she does swear. “Dirty bird” is still an insult. Her ‘alternative swears‘ feel all the worse because they clearly derive phonologically from ‘real swears’. Whatever she says puts any listener in mind of the original.

LACK OF BACKSTORY

Annie Wilkes is not a Minotaur Opponent, and that’s by design. In order to achieve the perfect movie pacing, Rob Reiner decided against including Annie’s backstory. This stands in contrast to the novel, which tells us quite a lot about Annie. (The timeline isn’t perfectly linear, opening with the car crash to hook us in, then showing us a staid discussion between Paul Sheldon and his literary agent in NYC, because now we’re wondering who this victim is.)

Lack of characterising backstory stands in contrast to another Stephen King adaptation Gerald’s Game, which makes heavy use of flashback to lay out character.

Yet it’s clear from watching the film Misery alone, that something made Annie the way she is. The screenwriter decided against backstory, but made sure to create a reason for why Annie is the way she is. We see glimpses of Annie’s traumatic childhood when she asks Paul for praise, “Did I do good?” and also from her explosive reaction when spilling the soup.

DID ANNIE WILKES CAUSE THE CAR ACCIDENT IN MISERY?

Audiences can find it difficult to accept big coincidences in fiction, even when in real life, massive coincidence happens more frequently than we’d expect. The massive coincidence at the heart of Misery: Annie Wilkes just so happens to find her literary idol in distress after a car crash.

Did Annie Wilkes sabotage Paul Sheldon’s car?

ARGUMENTS IN FAVOUR

- We learn Annie will stop at nothing. She has it in her. She’d be risking Sheldon’s death by setting up a car crash, but since the entire world revolves around her, she would feel a sense of control in making him careen off the side of a cliff. The outcome for him, as we know of malignant narcissists, is irrelevant. Control is everything. Push a button, something happens. That’s her idea of success.

- Also, Annie’s malignant narcissism/psychopathy intersects with a warped religiosity, in which she believes in destiny. She has convinced herself she and Paul are meant to be together in Heaven. Killing him wouldn’t be a sad ending with this world view.

- She reveals that she’s been following Paul Sheldon, and she could have done something to his wheels? She might loosen his wheel nuts or something as he stopped off for gas. He drives an unusual car in these parts, so it’s very likely Annie has had many opportunities to sabotage his car. However, the police officer is shown to be savvy. He knows immediately that Sheldon had been removed from the car. Surely he’d have noticed if the car had been tampered with.

- Instead, Annie could have tampered with the road. She could have used water to create black ice. As a longterm resident of the area, she’d know the exact conditions required to make black ice. She also has copious amounts of spare time to hang around waiting for Paul’s car to drive past. Locals would probably know how to drive in black ice, whereas Paul Sheldon clearly doesn’t, and she would have noticed this about him. However, it would be easier to tamper with the guy’s car than with the road.

- Paul’s car is distinctive. It’s distinctive because he’s driving a city car, an it’s old. It’s a 65 Mustang. No one else around these parts would be silly enough to drive that car in these conditions. (Note that the scriptwriters did not intend this reading:

- THE MUSTANG, rounding another curve, losing traction–

- CUT TO:

- PAUL, a skilled driver, bringing the car easily under control.

- Since Paul Sheldon visits the area every year, Annie could have been planning all this for years. It is revealed that she has stocked up on those red pills. Why? Wholly unknown to Sheldon, Wilkes has clearly followed him in her own bog-standard Jeep Cherokee and he’d never have noticed her. (As someone who looks like a middle-aged woman, she has a certain invisibility, as well.) Annie has easily kept out of view on those winding roads.

- Annie is later revealed to have a history of killing people and making it look like an accident.

ARGUMENTS AGAINST

- Paul Sheldon is a fool from the city. He’s been here many times before, and knew his writing retreat involved dangerous, snow-covered roads wending around the sides of cliffs. He’s driving at the most dangerous time of year. Yet he hasn’t hired a road-worthy vehicle. Ergo, the 1965 Mustang itself could have sent him off the road.

- Sheldon drives too fast. He’s got the music up loud, which can impact concentration and evinces a devil-may-care attitude to the road conditions.

- He’s feeling cocky because he’s a best-selling author who has just finished writing another best-selling book. He thinks he’s invincible, like too many celebrities who die because they weren’t wearing a seatbelt or were high on substances or whatever.

- Coincidences do happen, especially in small communities. Where the population density is low, the coincidence of Annie meeting Paul after his accident isn’t far fetched. She may not have even been following him on this particular day.

THE CHARACTERISATION OF PAUL SHELDON

WRITING ABOUT WRITERS

Stephen King likes to write about writers. This isn’t easy to do, because the life of a writer is mostly internal, and pretty darn boring without an excellent villain opponent. Secret Window is also about a writer. (Unfortunately the film adaptation stars Johnny D*pp.) Likewise, The Shining is also about a writer. (Unfortunately the film adaptation and subsequent publicity round exploited the very real mental illness of one of its main actors.)

MASCULINE VULNERABILITY

King is also good at explicating specifically masculine fears. Compare with his short story “The Tyger“, written long before Misery, King has an especial fear of the humiliation which comes from women being all up in a man’s business, with all mystique of his bodily functions gone. In the short story, a boy is humiliated by a middle-aged classroom teacher, who probably looks a lot like Annie Wilkes. The tiger in the bathroom is another metaphor for emotion — the emotion of humiliation. In Misery, we see the enduring theme for Stephen King. Annie shakes that bottle of urine like she’s mixing Kool-Aid. Meanwhile, the camera focuses on James Caan’s face. Paul Sheldon is immensely uncomfortable with a woman dealing with his pee. Anyone would be, for sure. But we see this pattern across Stephen King’s work and it’s gendered. Men are expected to be the strong, powerful providers and protectors. When that role is reversed, it’s an assault on masculinity, and an assault on the self. Yet it usually is reversed, because it’s mostly still women doing the laundry, cleaning the toilet, and it was certainly almost always women doing these chores of cleaning and caring in the 1980s.

In 1963 Betty Friedan wrote about the feminine mystique. Stephen King explores the masculine mystique. Men in traditionally gender-divided relationships with women must somehow sustain the strong, mysterious self-image of themselves, and simultaneously learn to live with the reality that she’s seen the skiddies in your jocks.

THE AUDIENCE CHARACTER

Paul Sheldon is what we might call the Audience Character. (When Audience Characters make wisecracks and are given dialogue which seems aimed at the audience rather than other in-universe characters, I call them Choric Figures.) We feel as captured as Paul. Like Bella Swan of Twilight, this guy is boring and bland precisely so the audience can paste ourselves onto him. Sure, most of us aren’t wealthy, famous novelists, which is why he ‘doesn’t have airs’. We’re not constantly reminded of it. In that room, he’s just an ordinary guy.

After reading the film script of Misery, which is unusually full of director’s notes as far as scripts go, I’m convinced the writers (Stephen King and William Goldman) expected me to like Paul more than I actually did. He smokes unfiltered Lucky Strikes, but only one, and only when completing a manuscript. (Poser.) His insistence on driving an ancient Mustang along those snowy roads is supposed to say something about a harmless refusal to keep up with the times — this is a solid man of strong tradition. It seems to me this guy fancies himself an indestructible white-collar cowboy, and his decision not to drive a more appropriate vehicle — to the conditions — smacks of plain old arrogance at his age.

Paul Sheldon is written with no moral weakness to speak of. He is the perfect victim and is, on his own, extremely boring.

Libby: I don’t think Mr. Sheldon likes for things to be out of the ordinary. Considering who he is and all, famous and all, he doesn’t have airs. Drives the same car out from New York each time — ’65 Mustang — said it helps him think. He was always a good guest, never made a noise, never bothered a soul. Sure hope nothing happened to him.

Misery 1990

Except for this: Annie is a part of him.

Stephen King has revealed the metaphorical layer of this story: Annie is the human outworking of Paul’s addiction. So, reading the film another way, there is no character by the name of Annie. Allowing himself that one (unfiltered!?) Lucky Strike cigarette has plunged him right back into the throes of an old addiction. He goes on a solitary drug bender at the Silver Creek Lodge and hallucinates that he’s been captured by a part-woman, part-pig. He metaphorically wrestles with his addiction and comes up trumps, but only after authorities intervene because his publisher in NYC is getting worried about him and sends them to the Lodge to check his room.

WHAT ARE THE RED PILLS PAUL SHELDON TAKES IN MISERY?

These days ‘red pill’ refers to a process by which a person’s perspective is dramatically transformed, introducing them to a new and typically disturbing understanding of the true nature of a particular situation. But this meaning originated from the subsequent (1999) film The Matrix.

Red has a broader meaning of danger, of course, and foreshadows blood and violence.

(There doesn’t appear to be a drug in existence which is sold in blood red capsules, red at both ends, aside from empty gelatine capsules.)

The drug in the book is explained as Novril, a fictional form of codeine and opiate. This is what causes Paul’s relapse (not, as I deduce from the film, Paul’s rewarding himself with the cigarette and the single glass of champagne).

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF MISERY THE PIG

It is very clear after Annie’s playful but creepy mimicry of her pig that audiences are to regard Annie herself as a pig.

- Misery the pig

- the state of being miserable

- and Annie herself

are one and the same, as if Annie gave birth to the pig.

Clearly she didn’t literally birth the pig, but what are the bounds of her monstrosity? Did she become a midwife so she could feed murdered babies to her pig, thereby creating a creature which was a little more human?

People have long been fascinated by the image of a woman giving birth to a pig. See, for instance, the 16th century Italian tale called “King Pig”. A queen gives birth to a literal pig. Still, she thinks he’s great. She’s determined to raise him as a true and proper prince. This is all well and good until it comes time for him to find a bride.

If you’d like to hear “King Pig” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “King Pig” was published July 2020.

It is fairly well-known (apparently) that pigs will eat anything, including human flesh if given the chance. This is hardly surprising, since humans, in turn, eat pigs, with notable cultural exceptions around the world.

According to Reiner, the original story ended with Annie killing Paul and feeding him to her pet pig, Misery, then tanning his skin to use to bind the book he wrote while in her care, retitling it to The Annie Wilkes 1st Edition.

Misery still shocking 25 years later

I decided to investigate pigs in the medieval era and found someone (Dr. Jamie Kreiner) has written a book specifically about early medieval pigs in the West.

From North Africa to the British Isles, pigs were a crucial part of agriculture and culture in the early medieval period. Jamie Kreiner examines how this ubiquitous species was integrated into early medieval ecologies and transformed the way that people thought about the world around them. In this world, even the smallest things could have far‑reaching consequences.

Kreiner tracks the interlocking relationships between pigs and humans by drawing on textual and visual evidence, bioarchaeology and settlement archaeology, and mammal biology. She shows how early medieval communities bent their own lives in order to accommodate these tricky animals—and how in the process they reconfigured their agrarian regimes, their fiscal policies, and their very identities. In the end, even the pig’s own identity was transformed: by the close of the early Middle Ages, it had become a riveting metaphor for Christianity itself.

With Annie animalified as a pig, she seeks revenge on Paul as Human, as humans have treated pigs since Medieval times.

| MEDIEVAL PIG FACT | IN RELATION TO MISERY |

| Farmers slaughtered almost all their pigs before they reached their third birthday, and many of them much earlier. (Breeding sows and stud boars excepted.) | Annie Wilkes ends people’s lives early, not just meaning to kill Paul off before his time, but also those babies who had no chance. Paul is Annie’s ‘stud boar’ until he stops doing as she wishes, and then she slaughters him. |

| Unlike other farm animals (used for milk/manure/wool/hides and so on) pigs were only bred for their meat. They were destined to be butchered. | Paul has only one use as far as Annie’s concerned. He’s a writer. He’s not a fully-fleshed human being in her mind. |

| Even cultures which loved to eat pig meat (Christians) still vilified them: ravenous, greedy, dirty, destructive. This reputation perseveres across time. | Annie loves what Paul produces, but we see her deal with his excrement, we see her butcher him. She both loves and hates him. |

| Christians have had an especially love-hate relationship with pigs. (What does the Bible say about pigs?) | Annie Wilkes uses Christian doctrine to justify her cruelty. |

| Though humans have vilified pigs, we have long been capable of holding ambivalent thoughts about them. Alongside their terrible aspects, they are smart and each have their own temperaments. They’re good at solving puzzles and are great escape artists. | A newspaper clipping shows Annie as valedictorian of her class. She also considers herself as adept as a doctor. She’s clearly smart, but in a dangerous way. She also has her own unique… personality, you might say. Annie thinks on her feet really well with the police officer turns up on her doorstep. |

| Domesticated pigs have a wild animal equivalent (boars). Boars have long been feared and respected for their strength and fury. They can easily kill humans. Tusks are at the exact right height to penetrate major arteries. | This maps onto the split personality of Annie: One the one hand a benevolent aunt, next minute a wild, untameable creature who appears to have emerged from the woods. |

| In medieval culture, people considered boars male, despite the reality that boars come in both male and female. (This is like how little kids often think of cats as girls and dogs as boys.) Obviously people understood the reality of boar sex, but the species in its entirety was considered masculine. | We first see Annie’s entire body as she hefts Paul out of his Mustang to her Jeep. This is the wild boar aspect of Annie, who becomes a domesticated pig in her own home. She displays the (false) care typical of maternity, but in the wild she displays formidable masculine strength. |

| Medieval pigs were smaller than most breeds today and free-ranging, so more muscular. If Medieval paintings are to be believed, they came in a variety of colours, but mainly brown. | This describes Annie Wilkes. Short, stocky, muscular, brown hair. |

| In the Middle Ages pigs lived on farms but also free-ranged a lot, for example in the woods that were considered extensions of farms, and also in towns. Their habitat changed depending on the time of the year e.g. hanging around nut trees when nut crops fell. | This describes Annie as well. She doesn’t range far from her farm, but she is seen in town and elsewhere. Like medieval pigs attracted to nuts, Annie would hang around the Lodge at times of year Paul Sheldon was expected to show up. |

| Pigs cause damage wherever they go, because they are really good at rooting and eat almost anything. (They also learn really well from each other e.g. if one pig learns to jump the fence, all the pigs can jump the fence.) When towns became bigger, towards the middle part of the Middle Ages, bylaws had to be put in place to prevent pigs from fouling up the waterways and so on. Gradually, farmers with pigs who caused damage were expected to pay for damages or a fine. (It was only a few hundred years ago that pigs were banished from city areas, which caused another problem: Now there was no one picking up the trash.) | Likewise, Annie Wilkes leaves a trail of destruction wherever she goes and has spent time in prison. |

| Farmers know this better than city folk, but pigs are dangerous animals. Keep your distance. Pigs can be homicidal. We know they’ve killed babies too, because in the Early Middle Ages cradle design evolved to prevent pigs from knocking a baby over. | Likewise, Annie is a danger to babies. She’s ‘omnivorous’ in her capacity for consuming others. |

| Pigs could get to you even after death. Again, because of their excellent rooting skills, they could dig up a dead human body if not buried without the proper measures. | Annie, like pigs, is a murderer who just won’t quit. Even when Paul is close to death, after she maims his legs (and hands), she still goes at him. |

| Despite all the trouble (and murder) pigs caused, they were very valuable to humans precisely because of that. A family may not be able to afford to keep livestock if they had to feed it, but a pig could be set free to scavenge, so a pig was basically free livestock. They basically converted the terrain into pork e.g. by eating dropped acorns, which had no other use to humans. Pork is also great for curing, and very tasty, so you it lasts all winter. | Likewise, Annie is both necessary and deadly to Paul. She’s keeping him alive, but also keeping him in a ‘pen’. |

| In the Middle Ages, the only way to kill a wild boar was a close up fight. You couldn’t kill a wild boar from a distance like you could with a deer. | The tousle at the end between Annie and Paul is not only reminiscent of a messed-up love-making scene, but recalls the Medieval hunters with their wild boar. |

| Theologians have come to realise that pigs are a ‘window’ into how peoples understand better how God put stuff together and why. Because pigs were the only animal raised specifically for meat, pig meat was a metonym for meat (and flesh) more generally. Their meatiness stands for sacrifice. Jesus sacrificed his flesh for Eternity; and so do pigs. | Annie has delusions of grandeur (while pretending to be humble at times). She takes her piggy role seriously. Divinely, even. And she considers herself a martyr in service to Paul, who she considers so omniscient and god-like that he can bring entire (fictional) worlds into being, and also kill them dead at a time of his own choosing. |

| It was well-known from the Middle Ages onwards that you have to think like a pig in order to understand them. | The Hitchcockian film editing which switches POV back and forth from Paul shows us how Paul is trying to get inside the mind of Annie the Pig. |

For more on pigs, listen to various interviews with Dr Kreiner:

- Episode 133 of the Then Again Podcast: How Pigs Transformed the Early Medieval West. “Dr. Jamie Kreiner joins Glen to discuss her book Legions of Pigs in the Early Medieval West which explores the ways in which pigs impacted early medieval culture, daily life, politics, and even religion.”

- New Books In Archaeology: Legions of Pigs in the Early Medieval West at the New Books Network

IS MISERY AN UNREALISTIC PORTRAYAL OF VIOLENCE?

Unfortunately not. A number of heinous real life crimes exceed the violence depicted in the film. To name just a few:

- The Hillside Stranglers

- Box in the Case

- New Zealand’s children in suitcases

- Annie Wilkes is inspired by real-life Genene Jones of San Antonio, believed to have killed between 46-60 children in the space of two years as a paediatric nurse. In prison, she tried a variety of religions including Judaism and Hinduism, then became a born-again Christian.

Despite the disturbing ‘Hobbling Scene’, Stephen King’s novel is far more violent than the film adaptation. In the novel Paul Sheldon loses a thumb, for instance. To include all of King’s violence would result in schlock shock on screen (and for me, the film would be unwatchable). Judiciously, Rob Reiner eventually understood (after pushing with his team for more violence) that less is more.

HOW GORY IS MISERY?

The one violent scene of the hobbling (which you’ll probably see coming) is awful. I recommend violence-avoidant audiences turn away from this one scene. The rest of the film will likely be okay, until the final tousle involving the typewriter. Perhaps turn away for that one, too. You’ll know what he’s planning because we are shown Paul weight-lifting with the typewriter.

Read this instead: Basically, Paul escapes from Annie by smashing her over the head with the typewriter. This isn’t enough to knock her out. She claws at his throat. They are both on the ground. Eventually Paul defeats her, though she’s like a machine herself. She keeps coming back long after you’d expect she’d be dead.

The important thing to know about this scene: Rob Reiner choreographed it like a sex scene. This is in keeping with the blurring of boundaries and exploration of opposites: mother as child, and here, love as hate. Of course, love is not the opposite of hate. Indifference is the opposite of hate. These things may appear to be opposites but are flipsides of the very same coin. Parenthood brings out the child in us, asking us to recall memories from our own childhood. Likewise, love and hate both call upon the most passionate parts of ourselves. It is absolutely possible to feel both emotions at once.

The duality can even be seen in the studio lighting, with its noir chiaroscuro efect revealing only one side of each character’s face. This suggests one is incomplete without the other.

After finally defeating Annie, Paul makes it into the corridor. Eventually the cops show up, looking for Sheriff McCain of course, who is dead in the basement.

Speaking of Sheriff McCain, the McCains feature in the film adaptation but not in the book.

Their marriage of many years is flirtatious, with just a hint of playful BD$M, in contrast to the genuine sadlsm going on inside Annie’s house:

Buster: Just leave it, all right?

Misery 1990

Virginia: Ooh, I like that tone.

These two really know each other well. There’s no pretence left. They know each other and love each other anyway. The death of Buster McCain is a true tragedy. This marriage juxtaposes against the totally fake love Annie thinks she feels for Paul Sheldon. She is incapable of real love, because everything revolves around her, and whatever Paul Sheldon can do for her. She can only ever be in love with her own created image of him.

With just two violent scenes, the film adaptation of Misery became a work of psychological horror, which is a better way of depicting character as we understand something of what motivates them. Reiner describes this story as a ‘psychological chess game’.

EMOTION BALANCED AGAINST VIOLENCE IN MISERY

David Lynch uses a term called ‘The Eye Of The Duck’ to describe a critical moment in film. Without this scene, the film falls over. This ‘Eye of the Duck’ scene really makes the story work.

Morbid Network film podcast Eye of the Duck discussed Misery and proposed which scene of Misery is The Eye of the Duck. I like this one:

The Eye of the Duck scene in Misery is Annie Wilkes contemplating the rain:

Paul: Annie, what is it?

Misery film script

Annie: (half turns away, turns back, gestures outside) The rain… sometimes it gives me the blues.

Annie, Close up. And sudenly it’s as if she’s been turned off, gone lifeless.

Paul, staring at her. No sound but the rain.

This scene resonates because it offers another side of Annie, neither childlike, motherly nor psychopathic. This feeling is universal, I suspect. Hence all the pathetic fallacy in stories involving tears, sadness and rain.

But perhaps you remember the hobbling scene best. It’s tempting to nominate this scene as the Eye of the Duck scene. But it would be a mistake to regard scenes of extreme violence as the most important. Sure, the film needs the violence because everything that happens beforehand promises it to us. The story structure requires it. But the story emotion requires a different scene, hence Annie Wilkes staring out at the rain.

This rain scene is another inversion on a romance trope:

The survey of 10,000 American members showed that weather has a significant impact on one’s libido. 95% of the women polled admitted they have fantasized about kissing in the rain, with over 57% attributing this fantasy to a Nicholas Sparks movie or book. According to the results of the study, the women are not the only ones whose libidos are affected by weather. 64% of men have admitted to being turned on during thunderstorms, with 43% admitting to hooking up during a weather-related power outage.

If You’ve Ever Been Laid During a Storm, You Owe Nicholas Sparks Big Time. It’s Science.

Anyway, emotion makes for an Eye of the Duck scene. A story which is all violence, or only violence and no emotion, has no resonance at all. The Eye of the Duck scene has emotional resonance. Few of us can identify with extreme violence. Many us can identify with feeling inexplicably blue after a long winter (or very hot summer) cooped up inside. Annie is basically feeling lonely. Everyone can identify with that.

Compare another blockbuster, Jaws, which in common with Misery, features a big, drawcard violent scene (involving the animatronic shark) but which also features a very important emotional scene: The so-called ‘Father and Son’ scene.

Brody is so distraught at the dinner table he can’t stomach food. His young son cheers him up in an adorable way. This is what bolster’s Brody’s spirits and propels him forward, to defeat the monster against community opposition. He’s doing it all for his son.

Few of us can identify with the task of killing a shark. Almost all of us can identify with doing something for the sake of a loved-one.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

The Kino Lorber Studio Classics edition of Misery

Disc 1: 4K UHD

- Audio commentary by director Rob Reiner

- Audio commentary by writer William Goldman

Disc 2: Blu-ray

- Audio commentary by director Rob Reiner

- Audio commentary by writer William Goldman

- Misery Loves Company featurette

- Marc Shaiman’s Musical Misery Tour featurette

- Diagnosing Annie Wilkes featurette

- Advice for the Stalked featurette

- Profile of a Stalker featurette

- Celebrity Stalkers featurette

- Anti-Stalking Laws featurette

- Season’s Greetings trailer

- Theatrical Trailer