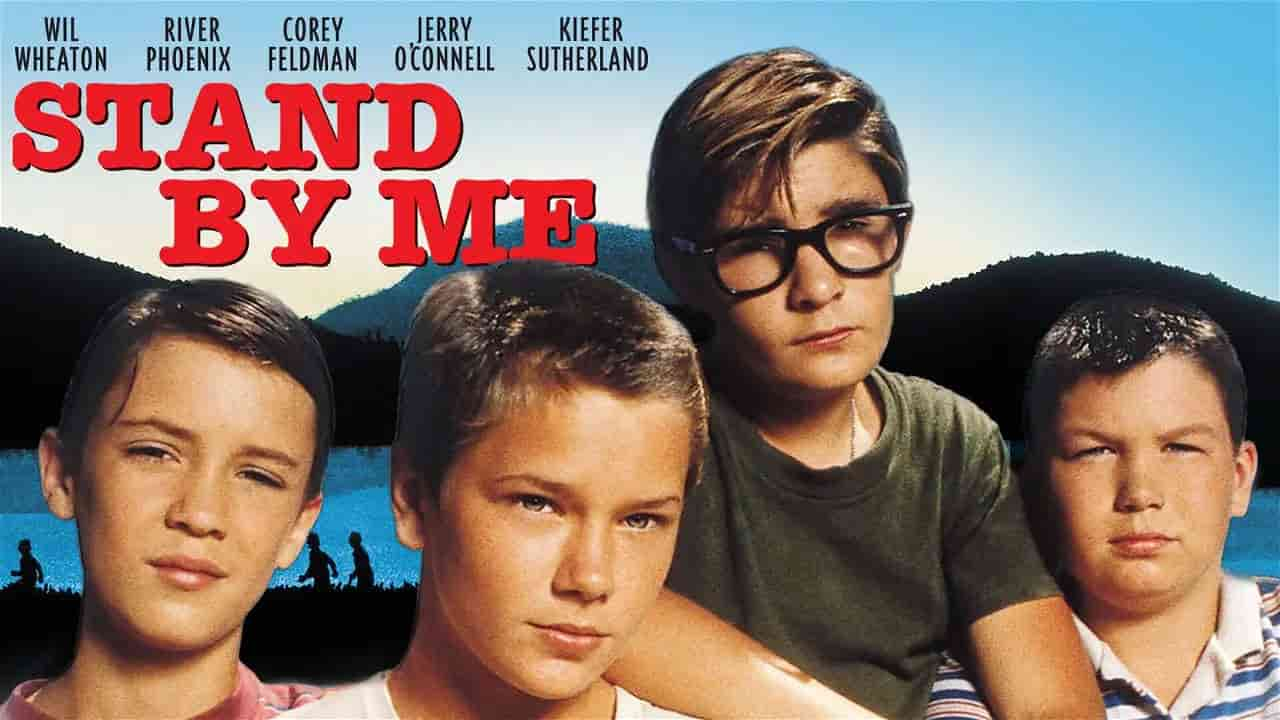

Stand By Me is 1986 a film directed by Rob Reiner, based on a Stephen King novella called “The Body”.

Alongside the Karate Kid franchise, The Breakfast Club, Dead Poets Society and a few others, Stand By Me is a tentpole coming-of-age film from my 1980s childhood.

Unlike The Breakfast Club (and especially Dead Poets Society), when I re-watched Stand By Me with my own kid this year it hadn’t aged badly at all. In fact, I got far more out of it than I had as an adolescent myself.

It brought back some memories, though. In the late 1980s, we were frequently required to sing “Stand By Me” in assembly at intermediate (the Aotearoa New Zealand equivalent of Middle School). Teachers knew the song from their own youth and because of Reiner’s film, it was doing the rounds again, bridging the middle-age, adolescent divide.

We sung “Stand By Me” one last time together on the final day of Form Two Year 8) before we were shuttled off to various surrounding high schools the following year. I vividly recall every single member of my class bawling their eyes out after hearing this song on our last day of childhood. Even the tough boys, even the kid called Gary, who at the age of 13 already looked like a jacked-up gym junkie, and who had misjudged the hinge-mechanism on a glassed door, tried to run through at speed, and now sported a jagged, badass scar all the way up his arm. I remember the pained and terrified look on his face when it first happened, juxtaposed against the tough guy who returned to school weeks later after a glorious stint in hospital, showing everyone his war wound.

I guess I remember that last day of school — and its resonant soundtrack — because I was the only one in our class not crying. Hell, I was glad to be getting the hell out of intermediate school. I had enjoyed a fairly easy ride, I guess, but still couldn’t for the life of me understand why everyone else wasn’t equally happy to be leaving our middle-school years in the dust. They seriously weren’t that great. (Five years later, I felt the same way about leaving high school.)

Or perhaps I had fallen victim to the very strictures evinced in Stand By Me. No way was I about to cry in school. No way. Not even when the tough boys were doing it, sitting together on the sunny field in one massive group catharsis.

WHAT HAPPENS IN STAND BY ME

It is the summer of 1959, smalltown Oregon. Four adolescent boys called Gordie, Chris, Teddy and Vern go on a twenty-mile hike in search of the body of a missing boy. When the story opens, the boy has been gone for several days and is the object of a police search.

At first glance, Stand By Me looks like the uber example of an Odyssean Myth, one of the three main types of modern myth, and by far the most common across the last three thousand years. Basically, Odyssean heroes leave home, go on a journey, encounter opponents, allies, go through a big battle, have a self-revelation and return home a changed person. (Sometimes they find a new home instead.)

There are several diegetic levels to this story: First is the story-within-the-story of adult Gordie returning home in the wake of Chris’s death. Inside that story, when the boys are in the forest, Gordie tells another story — about the Tri-County Pie-Eating Contest. This is an example of the carnivalesque. The purpose of the carnivalesque: challenging the norms of the dominant culture. On the surface, Gordy’s story is an example of gross-out, popular with kids between very specific ages, and indicative of the boys’ childlike interests. (They haven’t fully moved on to joking about sex.)

But the story isn’t just a gross-out tale. It is also a criticism of consumer capitalism. The hero-victim of this story is Davie Hogan. At first glance, this story seems to play into fatphobia. Gordie describes him as “our age, but fat, real fat.”) Gordie stresses it’s not his own fault, it’s “his glands”, which is neither here nor there when reading through a fatphobic lens.

But here the point is not to mock the fat Davie Hogan. Gordie’s story highlights the reality that, precisely because he is fat, Davie is an outsider. This is commentary on a community’s fatphobia. Gordie describes how he is bullied. Listeners are encouraged to identify with Davie, not with the bullies, or with the important people watching the pie contest. There’s nothing carnivalesque about the set-up. In carnivalesque events, there’s no line between spectators and actors. Everyone is equalised, yet in this little town Davie is othered by being watched. It is only when he throws up over the audience that the story turns carnivalesque. Now the audience is part of the performance.

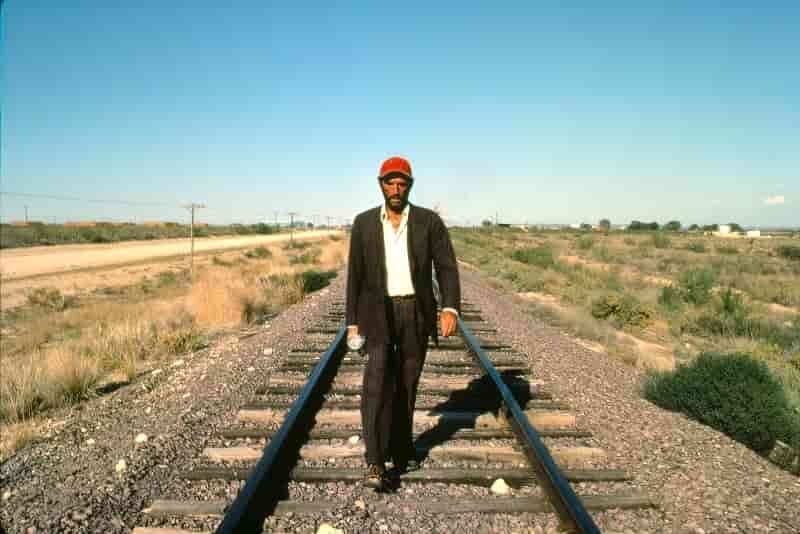

THE CHRONOTOPE OF THE RAILROAD

In stories, trains are highly useful as symbols. The railway line itself functions symbolically like a road. Roads are interesting because they are an excellent example of a chronotope, bringing time and space together as one inextricable little bundle. The chronotope of the road condenses a lifetime into a single image, offering audiences a birds-eye view of a lifetime, allowing us to understand cause and effect, moral dilemma and so on.

And how is a railway track different, symbolically, when it is used in story as a road? Well, railroad tracks contain a fatalism which roads do not. Roads can be left at any time. Although the boys in Stand By Me are walking along the railroad track, not hurtling forth on an unstoppable train, a feature of trains is that they can only travel along tracks. Likewise, these boys are being funnelled from boyhood into manhood, no returns, no other options. (It’s either manhood or death, as evinced by the dead boy.)

Of course, death is never far away when you’re walking along a railroad. The harrowing scene on the bridge captures the fact that death is all around, if not actually, then metaphorically.

THE MYTHIC STRUCTURE IN MIRRORED MINIATURE

THE MASCULINE MYTHOLOGY OF STAND BY ME

But I put it to you that Stand By Me is, very knowingly, a subversion of the ‘find yourself’ Odyssean mythic structure because the boys don’t find themselves at all. In this tragic journey from boyhood to manhood they lose something of themselves. They lose their right to be open and emotional with each other.

This is what makes Stand By Me a specifically masculine story, because girls cannot risk their position at the top of the gender hierarchy (girls are not at the top), and so do not face the specific form of loneliness which comes from men having to distinguish themselves as manly, individual, stoic and uncaring. Caring deeply for friends is for girls (and gays). Necessary addendum: Girls and femmes don’t escape as the lucky ones here, either. Girls are allowed to (expected to) keep their friends all the way through the teenage years and into womanhood, providing care and nurturing to others across the entire lifespan, propping up male partners oftentimes as their only support. A heavy charge indeed.

Basically, the dead boy’s body in Stand By Me is a metaphor for dead boyhood in the living main characters as they pass from childhood to manhood. And in case we miss what the film is really about, the final lines of the voiceover narration speak to the narrator’s sadness and adult loneliness, even though he has enjoyed a prosperous life as well-off family man:

Although I haven’t seen [Chris] in more than ten years I know I’ll miss him forever. I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anybody?

Stand By Me

THE REVELATORY POWER OF DIALOGUE IN STAND BY ME

Stephen King has an excellent ear for dialogue, especially the dialogue of masculine America. King’s ear for dialogue makes it into the film, and it’s the dialogue which propels this film into the stratosphere of greatness.

A 1987 paper by John L. Kijinski offers Stand By Me as excellent example of how discourse operates: “Bakhtin and Works of Mass Culture: Heteroglossia in Stand By Me“, Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 10, No. 2 (1987), pp. 67-81. He also says in a footnote that the dialogue in Stand By Me exceeds the novella in conveying Bakhtin’s theory.

So, first we need a bit of theory. (If you’re a writer, this may deepen how you think about dialogue in your own work. If you’re a student of literature, this will help you understand texts.)

What is THE MEANING OF heteroglossia?

Heteroglossia means multiple voices. It can refer to a diversity of voices, styles of discourse, or points of view in a literary work.

Example: In a novel, you might have the voice of the characters (dialogue) and the voice of the unseen narrator. These are two different voices, at least. We all speak differently to our friends, children, partners and work associates. This is heteroglossia.

The term heteroglossia was introduced by the Russian linguist Mikhail Bakhtin in his “Discourse in the Novel” (1934). Adjective: heteroglossic. (I’ve already mentioned several of Bakhtin’s ideas when talking about the railway tracks — the concept of the chronotope also comes from Bakhtin. The carnivalesque is also from the theory of Bakhtin.)

Introducing the term ‘heteroglossia’, Mikhail Bakhtin was starting a conversation about the presence of two or more expressed viewpoints in a text. He was interested in how that relates to power structures.

Bakhtin was saying there is no such thing as a single, solitary language which exists in a linguistic, literary, or existential vacuum, untouched and unaffected.

Even young children are capable of sophisticated manipulation of language. When they play, children appropriate social roles and rules in pretend scenarios and use a variety of ‘voices’ in role enactment. They are able to channel the dominant, ideological voice of the ‘official culture’. (For young children, that will be the adult caregivers in their lives.) Looking at the language of kids and adolescents is especially interesting because the way young people use language highlights the push and pull of dominant ideologies in people whose personal views are in the earliest stages of development. But there is never a point where various types of language stop competing to be the dominant voice.

Crucial to a proper grasp of Bakhtin’s theories around heteroglossia:

- Language is never neutral.

- Language is always ideologically charged.

- Language is the site where ideological conflict is fought out as well as recorded.

- The language of the ‘official culture’ is always trying to pass itself off as the one true language. Values and world views of the hegemony are in a state of constant testing. Those values and ideas are subsequently accepted or rejected or modified and subverted by the many other languages of the non-hegemonic groups.

- Each age group and each social class has its own different language.

- This pull and counterthrust can be observed between different individuals, but the conflict also happens within individual speakers, because we are in constant dialogue with the world of language around us.

- Bakhtin was super interested in language and how it interacts with value systems because he believed language shapes thought. He believed language is the formative material of human consciousness. Without language, no thought. Consciousness is a social structure. Our inner speech comes from the voices we have heard and always hear around us. We internalise those voices and make them our own.

- The word ‘logosphere‘ describes the constantly changing product of an individual’s interaction with the world of language. We create and recreate ourselves by interacting with others. Internal and external dialogue — it’s all important, all influential.

- One fascinating dimension of humanity open to exploration by fiction writers: How our inner dialogues are shaped, what we tell ourselves and others, how we form our views of the world based on what we hear around us. Whose voices dominate? Do characters accept the ideologies of these voices wholesale?

- Of course, writers don’t log language as it is used in life. No one does that except linguists doing field work. (And if you’ve ever seen linguists’ transcripts, they’re basically unreadable.) Instead, fiction writers are presenting what Bakhtin calls an ‘image of language’, meaning a dramatization of languages in conflict.

[Heteroglossia is] the teeming forces which jostle each other within the combat zone of the word.

Michael Holquist

Inside every word, Bakhtin maintained, there is a struggle for meaning, and authors can adopt various attitudes toward this struggle. They can choose to cap or muffle the dialogue, discouraging all outside responses to it, and thus employ the word monologically. Or they can emphasize the word’s so-called “double-voicedness,” by exaggerating one side (as in stylization); or by pitting two or more voices against one another while rooting for one side (as in parody); or, in a special, highly subtle category Bakhtin calls “active double-voiced words,” an author can work the debates inside a word so that the parodied side does not take the abuse lying down but rather fights back, resists, tries to subvert that

Emerson, C. (2011). POLYPHONY AND THE CARNIVALESQUE: INTRODUCING THE TERMS. In All the Same The Words Don’t Go Away: Essays on Authors, Heroes, Aesthetics, and Stage Adaptations from the Russian Tradition (pp. 3–41). Academic Studies Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21h4wh9.5

which is subverting it.

THE POLYPHONY OF STAND BY ME

Related word: Polyphony (multiple voices). This is another of Bakhtin’s words. He actually came up with polyphony before he came up with heteroglossia. The two words are now basically the same. If there’s a difference, it’s this, laid out by Saul Morson and Caryl Emerson (1990): Heteroglossia describes the diversity of speech styles in a language while polyphony is to do with the position of the author in a text.

Doesn’t matter. That’s almost too much terminology. What’s useful for writers and storytellers is this: The dialogue-heavy Stand By Me makes for an excellent case study in showing the constant dialogical interaction between different kinds of language. Each of these depicted languages is in constant competition with the others.

In his paper, Kijinski makes an inventory of those different, competing languages of Stand By Me.

- THE LANGUAGE OF AUTHORITY: For these four boys, the language of the official culture comes from judgements that might come from, say, parents and teachers.

- ABSOLUTE LANGUAGE: The judgments of custom, superstition, religion and the “general wisdom” of the community. Things that “everybody knows”. This language has special power because you don’t know who said it. It seems to come down from above. Saul Morson said, “indeed, it is precisely because they are authorless that they are most authoritative“.

- THE OPPOSITE OF THE LANGUAGE OF AUTHORITY: In this milieu, that’s the language of the gang of teenagers, slightly older than the main characters. The language of delinquent cynicism. (Two of the older boys are brothers of the younger boys.) These boys are portrayed as working class. They are close to, but not full caricatures of stereotypical 1950s tough guys. Much of their dialogue sounds like it was inspired by popular media of the era. These guys are all about success at the expense of others. They pride themselves on being hard. Feelings and emotions are minimised. Today we’d describe this as a toxic form of masculinity. It becomes clear over the course of the film that the younger boys have internalised much of what these older boys are saying.

- THE LANGUAGE OF CHILDHOOD: The younger boys haven’t quite left childhood, and their language makes for excellent juxtaposition against the tougher argot of the older boys. They’re about to be put in ‘the man box’, as commentators such as Mark Greene would put it. By juxtaposing this childlike language against the tougher language of the teenage boys, this story is elevated from a simple Holy Grail story (find the dead body, go home) to a story about how boys become men, and what they must sacrifice of themselves along the way.

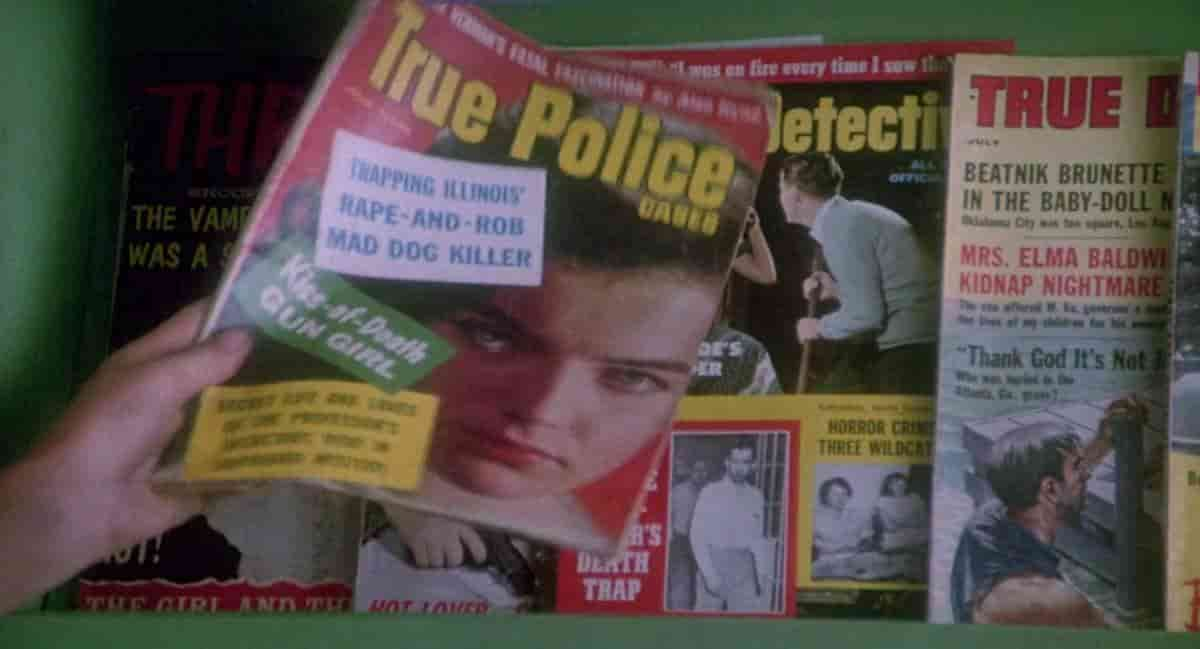

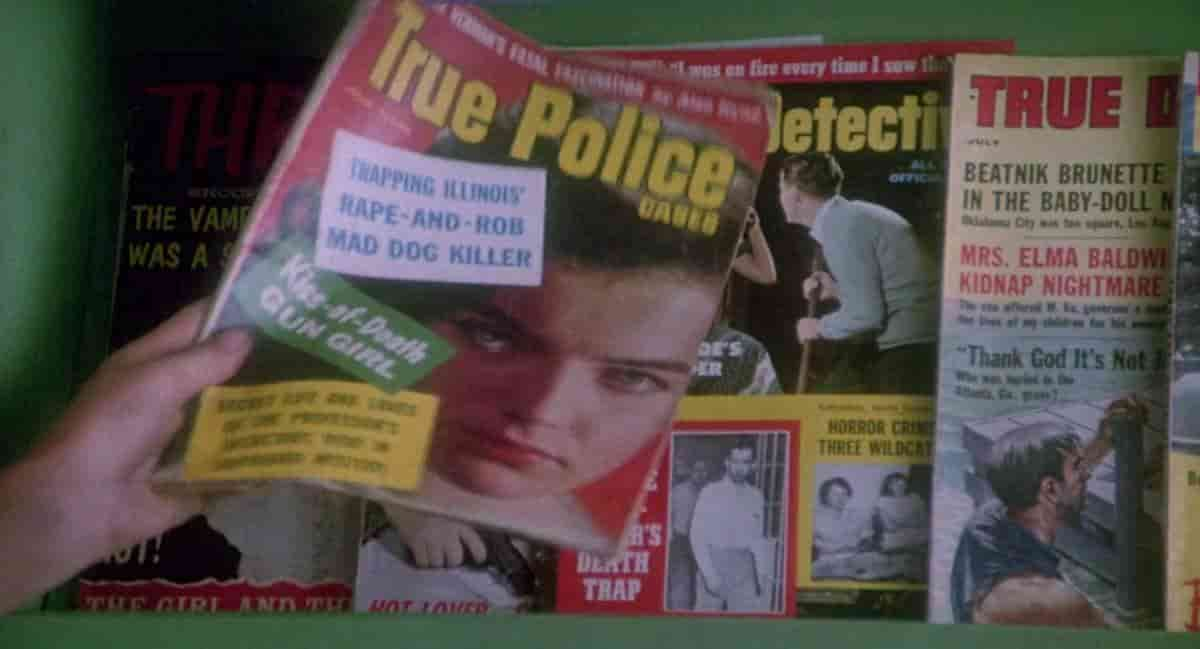

- THE LANGUAGE OF THE MASS MEDIA: This cuts across all groups in the community, demonstrating the power language has over all of us. Film, TV, popular fiction and music all influence both inner and outer speech. For these young characters, this language is ‘charged with imaginative power and possibilities’. The imaginative possibilities are clearly what drive these four boys to go on their expedition to find the dead body.

THE POLYPHONY OF STAND BY ME AS A VEHICLE TO CONVEY THEMES

(Here’s a link to the film script.)

The major, undergirding conflict of this film isn’t about the bully big-brothers versus the little kids. It’s not about some criminal who may have been involved in the dead boy’s murder, though the dim possibility of a lurking murderer lends an ominous vibe to the setting.

No, this story concerns the conflict within the boys themselves, centring on the character of Gordie who is faced with the massive task of navigating his way from childhood to manhood.

- How much of himself is he willing to give up in order to survive?

- How will he make it alone in the world once his boyhood friendship group has dispersed?

Crucial to Bakhtin’s theory of heteroglossia: The pull and counterthrust of language can be observed between different individuals, but the conflict also happens within individual speakers, because we are in constant dialogue with the world of language around us.

Stand By Me has a deceptively simple structure. In fact, by borrowing the ancient Odyssean mythic structure, the story does nothing new with plot structure whatsoever. Now, let’s take a moment to consider the supreme difficulty of telling a story about internal conflict, especially on screen (as opposed to on the page, with its broader capabilities for conveying thought). In a film, any internal conflict must have its outworking externally, because an audience cannot see into a character’s head.

Sure, we have the mean big boys, we have the unsolved mystery (and criminal) around death, and the tragedy that happened to Gordie’s family before the story opened. (The ghost.) Just because conflict is mainly internal doesn’t mean writers can skip out on those other layers of conflict.

But fewer writers find a way to fully explore internal conflict in new and interesting ways, revealing theme. Here, Reiner (and King) stage coming-of-age conflict very well, by conveying via the boys’ dialogue five different ‘languages’ listed above, each in constant conflict for supremacy inside Gordie’s head.

That which is authoritative gains real authority only when it becomes a part of our own inner speech, and this happens only after we test the authoritative speech in two ways; it is placed in dialogue with what is already authoritative within our inner speech; and it is also tested against the language of others who will help determine whether we accept, reject, modify, or subvert this new language.

John L. Kijinski

EXAMPLES OF LANGUAGE CONFLICT FROM THE TEXT OF STAND BY ME

ABSOLUTE LANGUAGE AND CHRIS CHAMBERS

Chris Chambers was the leader of our gang and my best friend. He came

Narrator of Stand By Me

from a bad family and everyone just knew, he’d turn out bad. Including Chris.

The phrase “everyone just knew” gives it away: This is a clear example of what Bakhtin called ‘absolute language’. Remember, when no one knows who said it, the ideas become even more powerful. Chris seems to be on a fated path to nowhere. (Again with the fate, cf. the railway track.) Also right there on the page: The ‘fact’ of this statement has been internalised by all of the characters. This has become the dominant voice of the community and shows the persuasive power of internalised judgements.

Chris: Teddy’s crazy.

Stand By Me, the junkyard scene

Teddy: Come on men! Move it out!

Gordie: Yeah.

Chris: He won’t live to be twenty I bet.

Gordie: Remember the time you saved him in the tree?

Chris: Yeah. You know I dream about that sometimes. Except in the dream I

always miss him. I just get a couple of his hairs and down he goes. It’s weird.

Gordie: Yeah. That’s weird. You didn’t miss him. Chris Chambers never misses,

does he?

Chris: Not even when the ladies leave the seat down. Hey, I’ll race ya!

GORDIE’S OFFICIAL PRONOUNCEMENT ABOUT CHRIS

Gordie’s switch to third person when he says, “Chris Chambers never misses, does he?” sounds like an official pronouncement. As Kijinski puts it, this ‘makes it sound like a final judgement, one that is insulated from the reversals of history’. (Once again we have a linguistic contribution to family of fatalistic motifs in which time only marches forward; there’s no going back to childhood, not ever. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.)

TEDDY’S SUBVERSIVE NARRATIVE ABOUT HIS WAR HERO FATHER

Another example of the same technique:

Milo: I know who you are. You’re Teddy Duchamp. Your dad’s a loony. A loony

Stand By Me, in which the boys are about to be chased off the junkyard when the junkyard guy has a dig at Teddy for his PTSD-suffering father.

up in the nuthouse at Togus. He took your ear. And he put it to a stove. And he burnt it off.

Teddy: My father stormed the beach at Normandy.

Milo: He’s crazier than a shithouse rat. No wonder you’re actin’ in the way

you are. With a loony for a father.

Teddy: You call my dad a loony again and I’ll kill you.

Milo: Loony, loony, loony.

Teddy’s father has been declared insane and put in an institution. (PTSD was not proposed as a diagnosis until 1980.) This is the ultimate judgement from an authoritative voice. But Teddy is inverting the script, rejecting it. We can deduce from its repetition in this scene that Teddy has said this line many times before, if only to himself: “My father stormed the beach at Normandy.” This is an example of polyphonous (two) voices competing for dominance in Teddy’s head: his father as worthless; his father as war hero.

This is Teddy’s attempt at subverting the dominant, hegemonic discourse. (Everyone on town would subscribe to the ‘crazy’ story.)

GORDIE’S USE OF THE LANGUAGE OF STORYTELLING TO SHOW EVERYONE IS WORTHY OF RESPECT

When Gordie tells the story-within-the-story of Davie throwing up all over the spectators at the pie-eating contest, this is an example of Gordie taking the language of storytelling (specifically the tall tale) and takes symbolic control of a power imbalance. When the audience all start sympathy vomiting on each other, they are shown to be made of the same stuff as fat Davie on the inside.

THE ENDING

Ultimately, John L. Kijinski didn’t think much of the ending to Stand By Me. After spending the entire film criticizing capitalism and what we would now call toxic masculinity (though it wasn’t called that back in the 1980s), the men have each led different lives: Two of them are stuck in menial jobs leading lives of insignificance; Chris becomes a lawyer though his life his cut short; and the storyteller lives in a mansion with the wife and the kids. He seems to be a Stephen King stand in, having made his money from writing (or similar) in a fancy home office.

Moreover, Kijinski feels the ending of the film is prefigured by the ending to the story-within-a-story about Lardass — the ending Teddy cannot abide when he asks, “What happened? How can that be the end? What kind of ending is that? What happened to Lardass?”

Which leads us to the question: What makes for a good ending, and what is the responsibility of the storyteller? Stephen King and Rob Reiner have shown us a community, laid out how the social dynamics work, shown us how power is awful, how boys lose their close relationships with friends in the transition to manhood… And then shown us the natural consequence of that.

I must disagree with John L. Kijinski that the ending to Stand By Me is a let down. For what is the alternative? The narrator realises what’s going on (before hitting middle age, no less) and changes his life and the lives of the friends around him? That would have been utterly trite and unrealistic. Stand By Me is a tragedy, because sometimes tragedies are called for. It is a tragedy because, in the end, none of the boys have become free (dictated by the constraints of their gender). Lack of true freedom is always a tragedy.

Let’s return for a moment to Bakhtin, who came to his ideas via his deep interest in Dostoevsky, an author who ‘loosens the grip between hero and plot’.

Dostoevsky designs as the hero of his novels not a human being destined to carry out a sequence of events — that is, not a carrier of some pre-planned “plot” — but rather an idea-hero, an idea that uses the hero as its carrier in order to realize its potential as an idea in the world. The goal then becomes to free up the hero from “plot,” in both the sinister and humdrum sense of that word: from all those epic-like storylines that still clung to the novel with their routinized, and thus “imprisoned,” outcomes, and also from events in ordinary, necessity-driven, benumbing everyday life. For events — as the biographies of both Bakhtin and Dostoevsky attest — rarely made you free. Bakhtin all but suggests that we leave this pleasant illusion to Count Leo Tolstoy (one of the few great writers against whom Bakhtin actively polemicized), an aristocrat to the manor born who loved life’s delightful round of rituals, could afford to lose himself in it, developed an anguish of guilt about it, and came so powerfully to distrust language, that surrogate for action. Dostoevsky invites his heroes and readers to experience the richer, more open-ended discriminations and proliferations of the uttered word, in a context where all parties are designed to talk back.

To be sure, in choosing to structure works in this way, the polyphonic author

Emerson, C. (2011). POLYPHONY AND THE CARNIVALESQUE: INTRODUCING THE TERMS. In All the Same The Words Don’t Go Away: Essays on Authors, Heroes, Aesthetics, and Stage Adaptations from the Russian Tradition (pp. 3–41). Academic Studies Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21h4wh9.5

is still authoring heroes and still “writing in” their stories. But by valuing, above all, an open discussion of unresolvable questions, such an author writes them into a realm of maximal freedom.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The Australian short story “Aquifer” by Tim Winton, which has a very similar mode of narration. A middle-aged man returns to his childhood home town after a crime story on the news and recalls the time he was adjacent to the death of another boy the same age.

FURTHER READING

Stand By Me serves as an excellent text for talking to boys about how friendship changes around adolescence, and how it doesn’t actually have to.

Serve with: The Little #MeToo Book by Mark Greene and his Remaking Manhood podcast about healthy masculinity.

Feminism isn’t the problem. It’s the solution. Our collective problem is our dominance-based culture of masculinity which relies on the hourly denigration of the feminine to bully young boys out of emotional expression and connection.

Once we’ve broken their emotional expression and connection in the world, men are slotted into hierarchical dominance-based culture of masculinity where we are expected to dominate women and others around us as a shortcut to validating our masculinity.

Until we create a healthy culture of authentic masculine expression and connection, feminism will be where the battle is fought to protect boys, girls, men, women and non binary people from the millions of abusive dangerous men who remain trapped in our violent Man Box culture.

Why do we have feminism? Because we have a culture of dominance-based masculinity that targets the feminine at every level. It attacks everything from boys’ emotional expression to women’s bodies. Call yourself a feminist if you oppose that ugly one sided assault.

Mark Greene on Twitter Nov 27, 2022