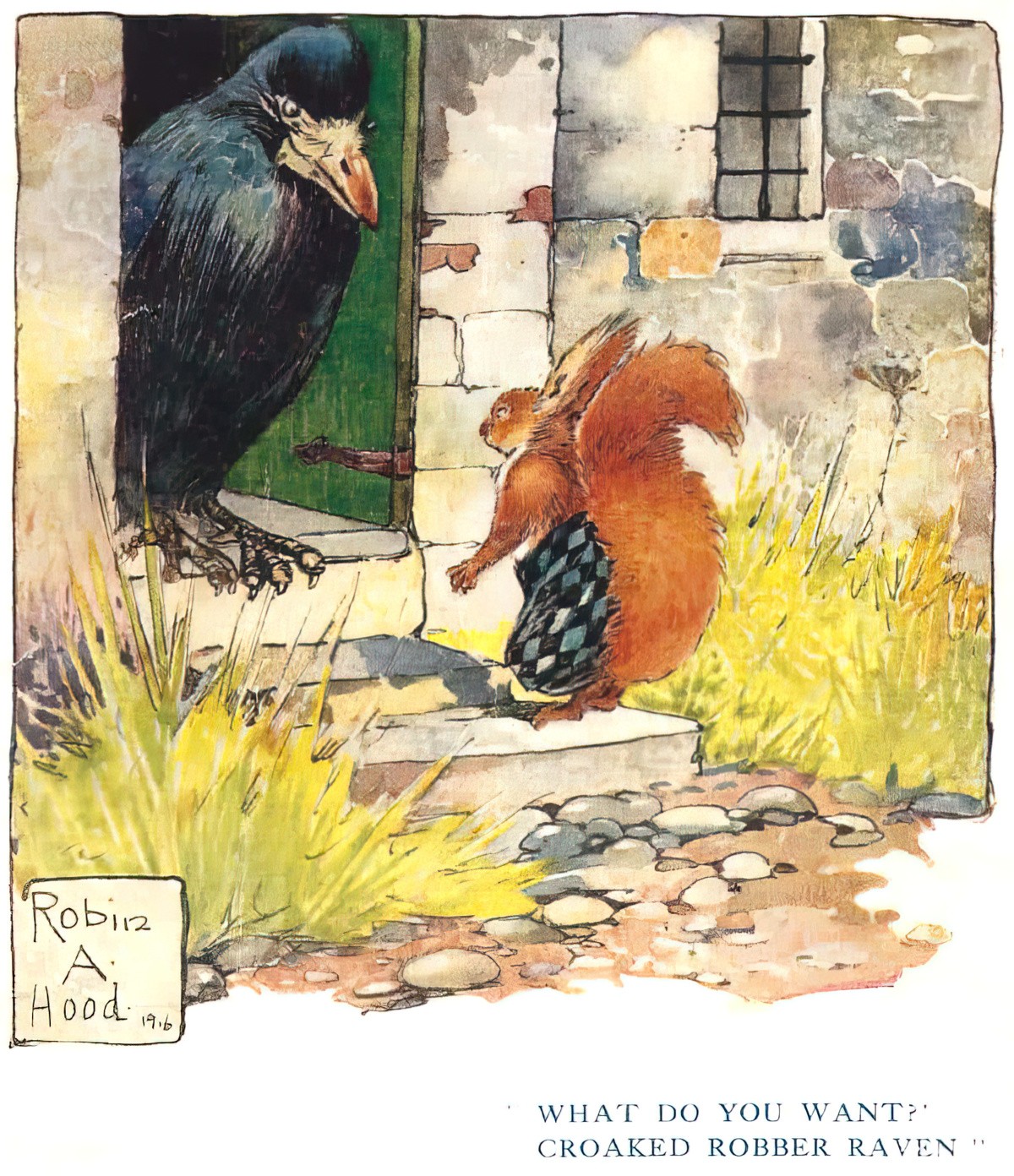

The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin (1903) is the second picture book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter. Squirrel Nutkin is an example of a story from the First Age of Children’s Literature, though Beatrix Potter herself did much to usher in the more modern style of children’s story.

Though the page turns and small size of the book are a vital component of the reading experience, you can read The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin at Project Gutenberg, as Beatrix Potter’s work is now in the public domain.

When you think of Beatrix Potter, you probably think of ‘talking animal’ stories. A while back I quoted a continuum of animal-ness in (mostly) children’s literature. We have humans in animal-shaped bodies at the top and outright ordinary animals at the bottom. (Or inversed, if you like.)

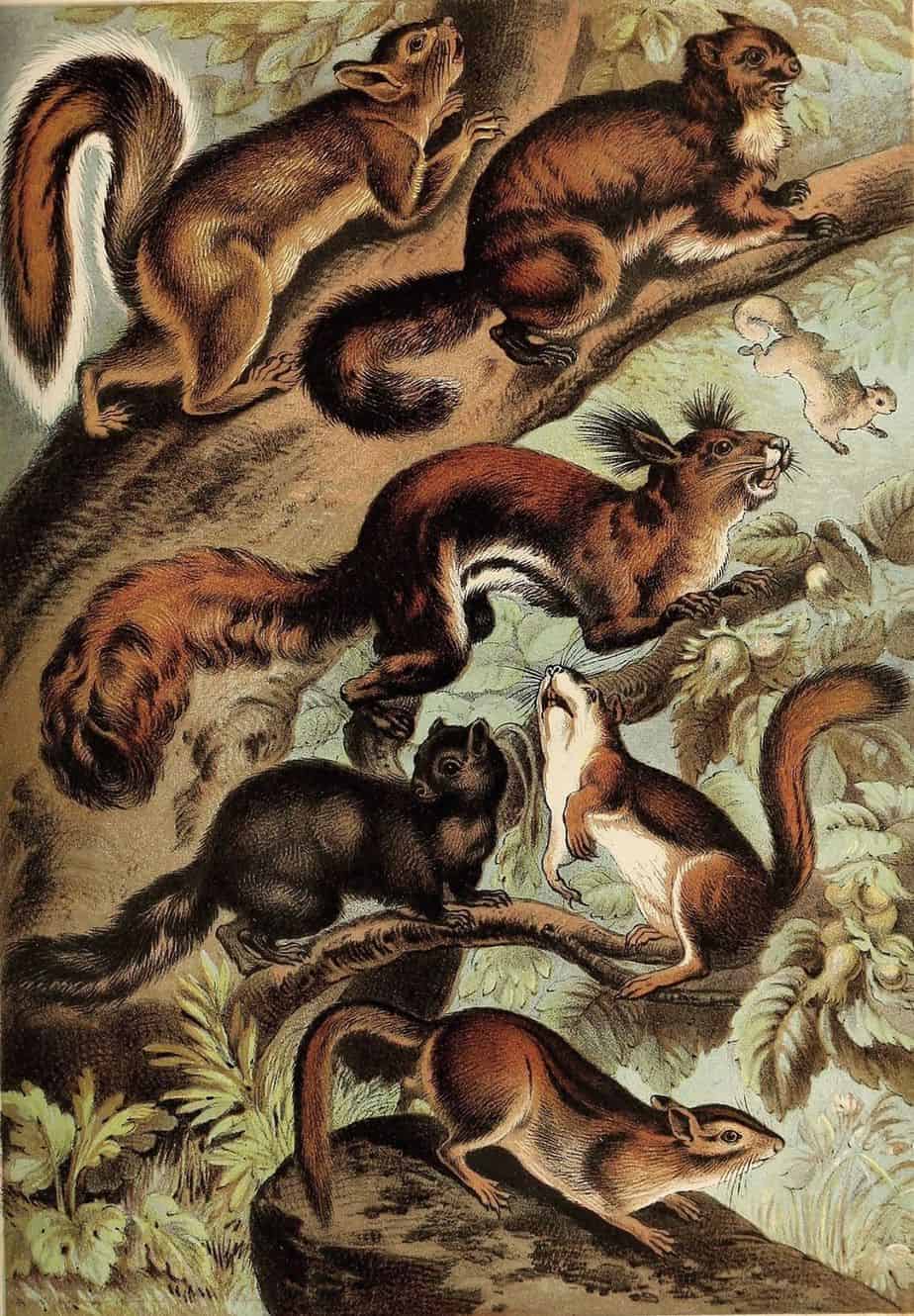

The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin is interesting in its inclusion of three different levels of animal-ness in the one story:

- The squirrels, who can talk (riddles) and who are basically children in the bodies of squirrels. Unlike Peter Rabbit in his little blue jacket, these squirrels are not wearing clothes, but they do use their bushy tails as sails for their log boats, which elevates them into the human realm.

- Then there’s their opponent, the owl, who never replies to the prancing and taunting. It becomes clearer and clearer to the reader over the course of the story that the owl perhaps can’t talk, even if he wanted to, because he is a plain old owl! He does live in a ‘house’ (a tree) with a door and he cooks his meat (presumably) because smoke comes out of his ‘chimney’. But apart from these human attributes, the possibility that he might eat the squirrels if he’s going to eat a mole is terrifying, because the squirrels have been making meaty offerings, all the while failing to realise that they themselves are meat.

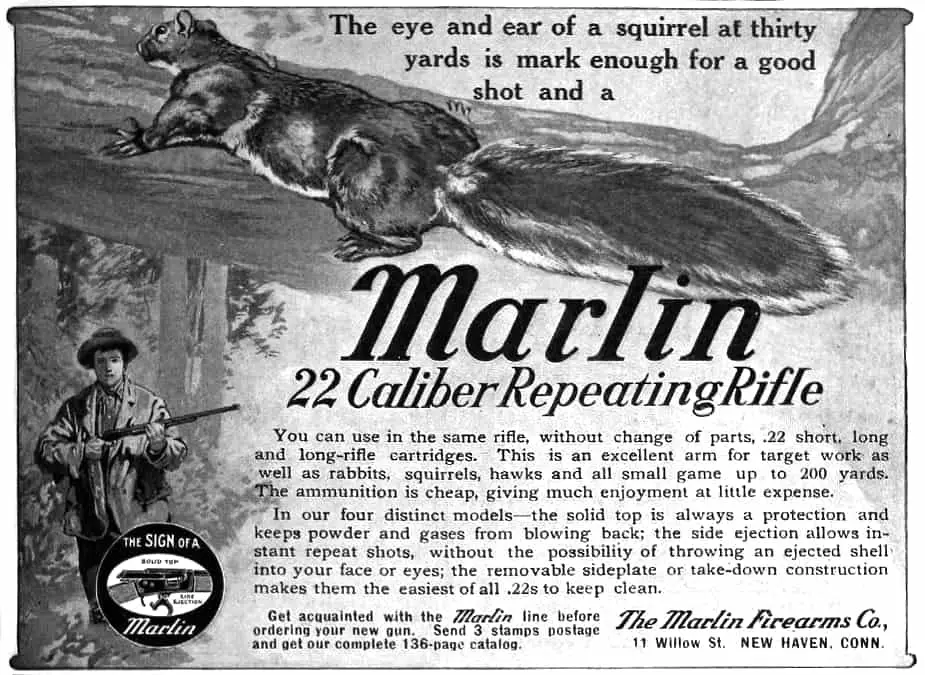

- And the offerings, of course, are the most animalistic of the characters, not the least bit personified. Indeed they are meat rather than animals—the three fat mice, the fine fat mole, seven fat minnows and so on.

So for me, reading Beatrix Potter is like being a kid watching David Attenborough documentaries with my father. First you’d feel sorry for the squirrel, pursued by the owl, then POV switches. Now I feel sorry for the poor, hungry owl. There’s no winning. No way to avoid the horror.

“It’s just nature,” my father would say, as I expressed alarm about a jaguar pulling down an antelope. “Everybody’s someone else’s meat.”

THE DANGEROUS STORYWORLD OF SQUIRREL NUTKIN

Unlike Dahl’s Matilda, Nutkin presents outlaw behaviour as opposed to promoting outlaw behaviour. Unlike Sendak’s Wild Things, Nutkin’s wild revels are no wild rumpus where the border between the fond and the fierce is terrifyingly blurred: “We’ll eat you up—we love you so!”

This is not the world of Beatrix Potter, but this is not to say her world is safe. The thing that all three have in common is danger, and it is the thing that makes their stories delightful for children, for childhood is the most dangerous thing in the world.

For all of her whimsy, Beatrix Potter never lost sight of reality, even its tensions and terrors. Peter Rabbit’s father was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor. Jemima Puddle-Duck’s eggs were devoured by her canine rescuers. Squirrel Nutkin was mutilated by Old Mr. Brown.

The world of Beatrix Potter is the real world: moral, but not moralistic; a world of pursuit and prey, of dangers and delights, of existence and enchantment.

Crisis Magazine

STORY STRUCTURE OF SQUIRREL NUTKIN

Does Squirrel Nutkin work as a story for you? Graham Greene didn’t think so:

Graham Greene called The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin “an unsatisfactory book” in comparison with Beatrix Potter’s earlier tales, and it deserves this designation only insofar as it does not satisfy the accepted formula of the nursery morality tale.

The ambiguity of Nutkin’s tale is very satisfying indeed. Whether or not Nutkin’s dismemberment is read as justice for nonconformity or a further celebration of nonconformity, what is more startling and poignant than the loss of Nutkin’s tail is the loss of Nutkin’s tales, as he proves unable to speak or sing after his chastisement.

Crisis Magazine

Scholars of children’s literature have identified a technique common to many children’s stories — the switch from the iterative to the singulative, in Maria Nikolajeva’s terms. This is where the author sets up the characters and the world via telling rather than showing:

This is a Tale about a tail—a tail that belonged to a little red squirrel, and his name was Nutkin.

He had a brother called Twinkleberry, and a great many cousins: they lived in a wood at the edge of a lake.

In the middle of the lake there is* an island covered with trees and nut bushes; and amongst those trees stands a hollow oak-tree, which is the house of an owl who is called Old Brown.

*Notice, also, how Beatrix Potter switched tense from past to present in her set-up. This is slightly unusual.

After the setting and main characters have been introduced, the story switches to the iterative (one-time event). This switch will be marked with something like, “One day, On this particular morning” or something like that:

One autumn when the nuts were ripe, and the leaves on the hazel bushes were golden and green—Nutkin and Twinkleberry and all the other little squirrels came out of the wood, and down to the edge of the lake.

Modern picture book authors more rarely make use of the switch from continuous to the iterative. Bear in mind, if you are making use of it, as many have done before you, the story will have an old-fashioned feel. Which may be fine, if that’s what you’re going for.

SHORTCOMING

Squirrel Nutkin is basically Peter Rabbit in squirrel form. He’s a fun, merry prankster who doesn’t see danger until danger almost kills him.

Today, mischievous childlike characters in picture books are the norm. But in 1903, Pollyanna, Goody-Two-Shoes characters who behaved properly as models were the norm. Squirrel Nutkin is a political little book, as all children’s books are, whether they mean to be or not:

Nutkin’s is the attitude that does not obsequiously succumb to the formalities of, say, nineteenth century landowners, despite their pride, power, and sovereignty. Nutkin is the ancient Squirrel of Mischief: the irresistible agent of insubordination that launches itself against the rigid systems of the world in the struggle between the playful and the pragmatic. The contract between the silly songs that ring through the woods and the serious industry and poise that rises above them is reflective of a reality that every child knows—and so does every parent.

Crisis Magazine

DESIRE

The squirrels want to collect nuts on Owl Island. Following human-like procedures, they decide to ask permission rather than just take them. Although Nutkin is a cheeky scoundrel, he’s doing things by the book.

OPPONENT

The owl, whose reticence makes him deliciously scary.

I read the owl as a godlike figure. When the squirrels make offerings they’re basically performing a pagan ritual to their god, who they think is probably listening, but they have to keep the faith.

PLAN

The squirrels make little rafts out of twigs and paddle over the water to Owl Island where they plan to ask permission from Owl, and then they’ll be allowed to gather as many nuts as they need.

They do this time and time again and the owl does not say no, so they conclude if they take offerings they’ll be allowed to continue.

BIG STRUGGLE

Unfortunately, Squirrel Nutkin does not take the entire ritual seriously, revelling in riddles and fun rather than affording the scary owl the respect he probably deserves.

Nutkin made a whirring noise to sound like the wind, and he took a running jump right onto the head of Old Brown!…

Then all at once there was a flutterment and a scufflement and a loud “Squeak!”

The other squirrels scuttered away into the bushes.

ANAGNORISIS

The ‘self’-revelation is a simple revelation—an unexpected, funny turn of events.

When they came back very cautiously, peeping round the tree—there was Old Brown sitting on his door-step, quite still, with his eyes closed, as if nothing had happened.

But Nutkin was in his waistcoat pocket!

What makes this funny? All this time the owl has been presented as an ordinary animal owl, and he’s not even wearing a waistcoat. Also, being in an opponent’s pocket foredooms being inside their stomach.

The anagnorisis—of the page—is that Squirrel Nutkin may respect the owl in future and not be so bold.

NEW SITUATION

Beatrix Potter knew that she couldn’t leave the story there:

This looks like the end of the story; but it isn’t.

If she had left the story at that, it would have felt cut short to the reader. Now we have the REAL big struggle scene, which is actually pretty gory to the sensibilities of the modern reader. Children of the first golden age kept chickens at home and saw them beheaded, they saw their cats give birth and their father drowning them… I feel confident in saying that children of 1903 had a closer connection to animal death than contemporary 2018 readers.

SECOND BIG STRUGGLE

Old Brown carried Nutkin into his house, and held him up by the tail, intending to skin him; but Nutkin pulled so very hard that his tail broke in two, and he dashed up the staircase and escaped out of the attic window.

NEW SITUATION

The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin ends in mythopoeic fashion, as a fictional, myth-like explanation for why squirrels behave as they do.

Cheeky squirrels who throw little sticks at you are definitely my own experience. Beatrix Potter has just explained why they’re so cheeky and timid at once:

And to this day, if you meet Nutkin up a tree and ask him a riddle, he will throw sticks at you, and stamp his feet and scold, and shout—

“Cuck-cuck-cuck-cur-r-r-cuck-k-k!”

What Does Mythopoeic Mean?

Authors who make up their own mythologies for the sake of a setting are said to be writing ‘mythopoeic’ stories.

Mythopoeia is a narrative genre in modern storytelling where a fictional or artificial mythology is created by the writer. Tolkien coined the word, and Lords of the Rings remains a standout example. Harry Potter is another.

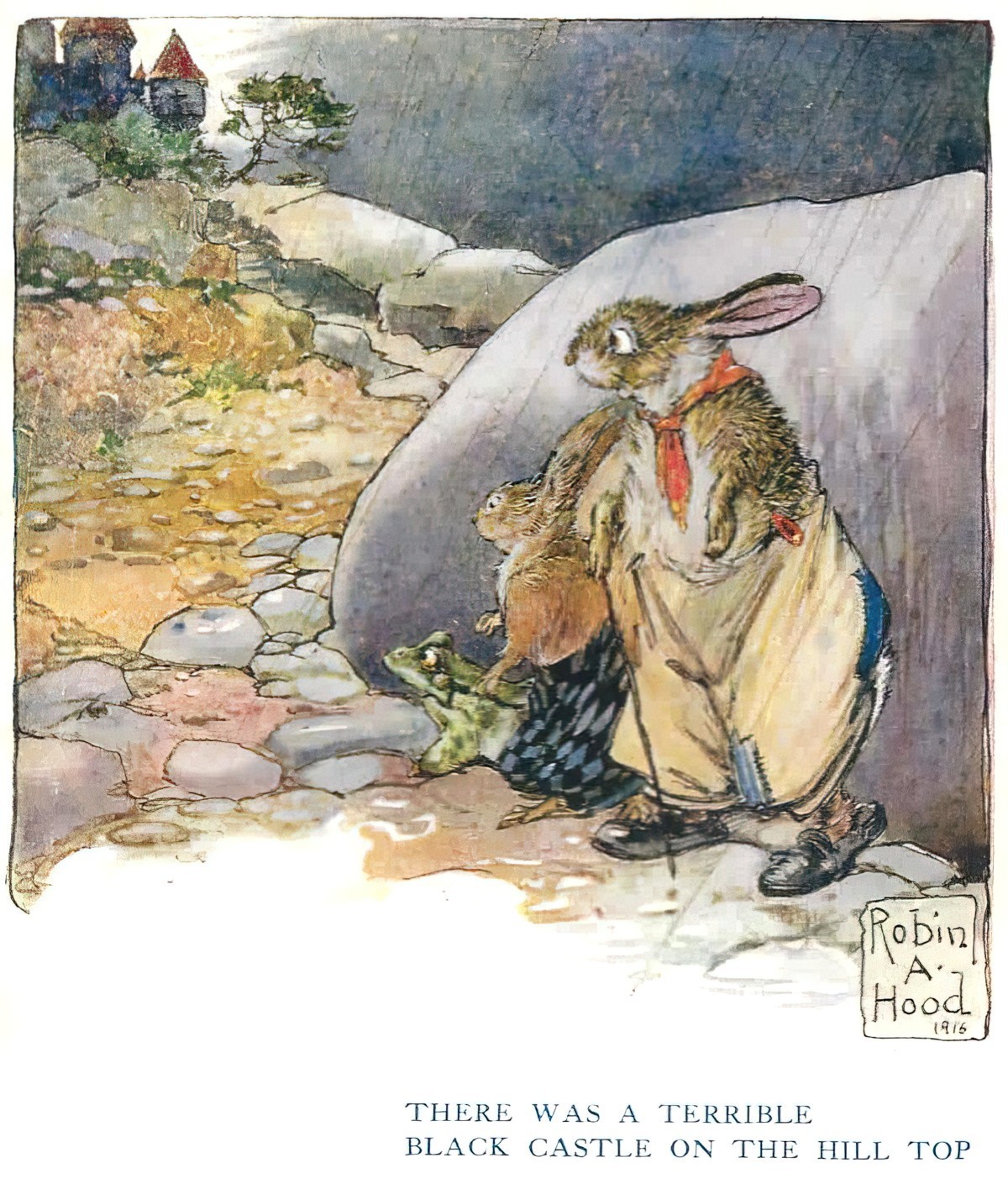

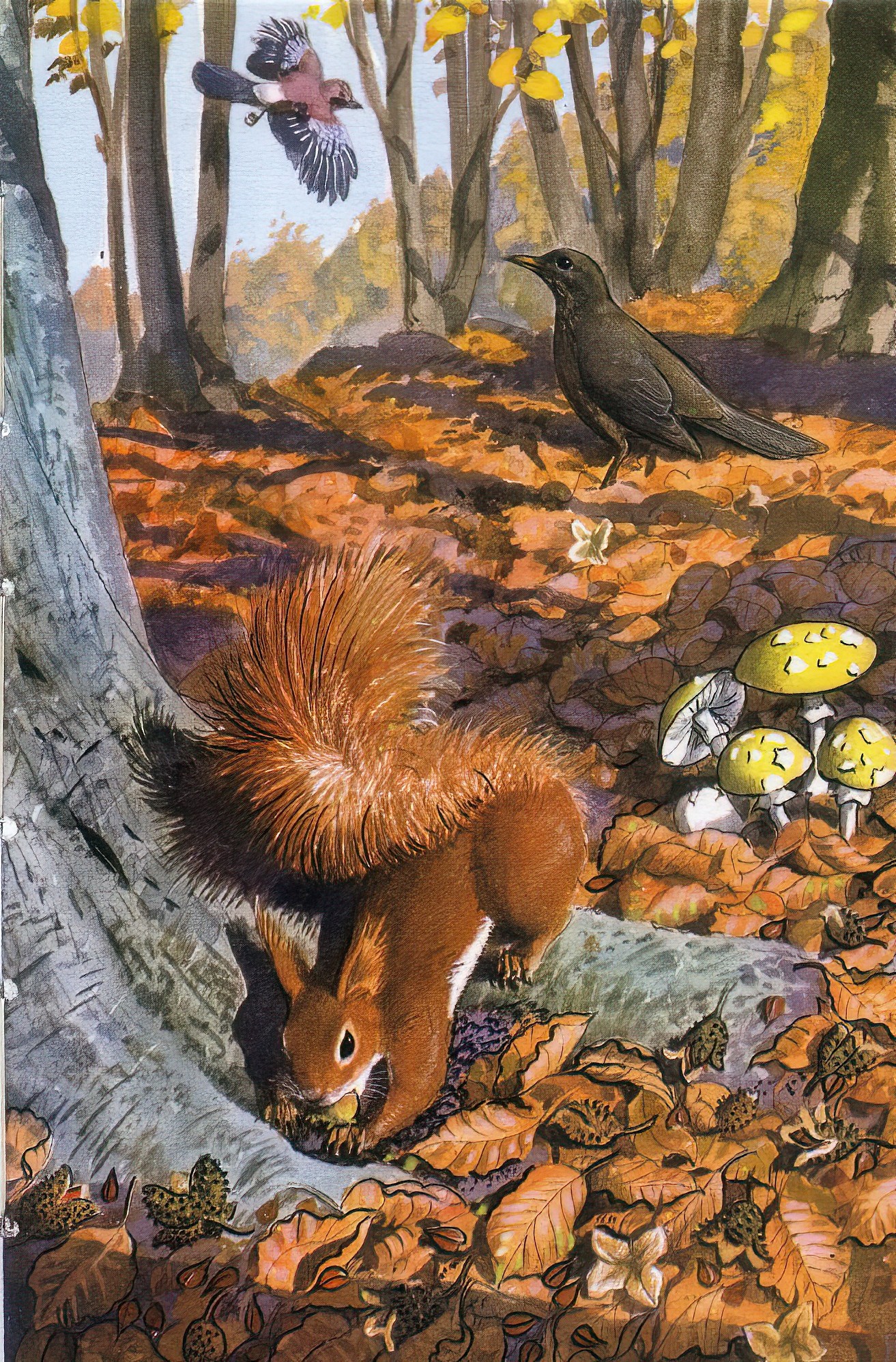

MORE SQUIRREL ILLUSTRATIONS FROM CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

![Marie-Madeleine FRANC-NOHAIN [1878-1942] Alphabet In Pictures 1933 squirrel](https://www.slaphappylarry.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Marie-Madeleine-FRANC-NOHAIN-1878-1942-Alphabet-In-Pictures-1933-squirrel.jpg)