**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Spaceships Have Landed” by Canadian author Alice Munro is the only story in the 1994 Open Secrets collection which was not first published in The New Yorker. This one was published in The Paris Review, Issue 131, Summer of 1994. These days you can read it online at The Internet Archive. If you don’t have the book, I recommend copying and pasting onto a word document, then altering the font and spacing for easier reading.

This is a long short story running over 10,000 words. But after you’ve read it, you’ll feel like you read an entire novel. With perfectly chosen narrative summary and a roving point of view, Alice Munro paints the story of a 1950s town, as experienced by two very different young women united by the timing of their coming-of-age.

You cannot let your parents anywhere near your real humiliations.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

OPEN SECRETS (1994)

- “Carried Away” in the October 21, 1991 edition of The New Yorker

- “A Real Life” in the February 10, 1992 edition of The New Yorker

- “The Albanian Virgin” in the June 27, 1994 edition of The New Yorker

- “Open Secrets” in the February 8, 1993 edition of The New Yorker

- “The Jack Randa Hotel” in the July 19, 1993 edition of The New Yorker

- “A Wilderness Station” in the April 27, 1992 edition of The New Yorker

- “Spaceships Have Landed” in The Paris Review, Issue 131, Summer,1994

- “Vandals” in the October 4, 1993 edition of The New Yorker

THE STORY IN A NUTSHELL

“Spaceships Have Landed” is the story of a small community. The story opens with a missing young woman, but this isn’t about the missing young woman. Instead, a missing character opens cracks in a community which is rotting at the base.

One summer night, 19-year-old Eunie Morgan goes missing from her home at the derelict end of town, where she lives with her ageing, vegetable-grower parents in a flood-prone street. The parents go out looking with a torch but don’t find her.

SETTING

It is 1953, the small town of Carstairs in Southern Ontario. Nearest city Hamilton.

The Morgans don’t have plumbing yet. There’s a seat on the veranda which was reclaimed from the side of the road. It makes for a perfectly good, abandoned car seat. In this way, Munro shows us that this is not a wealthy family.

It is night-time and it is summer. Munro’s description reminds me very much of a very good Ray Bradbury story “The Night”. Bradbury writes in second-person with the focalising character of reader as child. (A fascinating narrative choice.) Similarities are limited, but in both stories, a family member has gone missing. In the Bradbury story, mother and child go searching for an elder brother through a ravine — a personified (monster-fied) ravine which ‘eats people’ (metaphorically). Alice Munro, too, makes the hot, summer night come alive in “Spaceships Have Landed”:

- The trunks of the plum trees are ‘crowded in like watchers, crooked black animals.’ (In Ray Bradbury’s story, apple and oak trees contribute to a cosy, safe vibe, juxtaposing against the hungry ravine lurking nearby. Here, plum trees fulfil a similar function; normally hygge, suddenly ominous.)

- Instead of an ominous ravine, we have an ominous river. The Morgans are the last on their road, meaning their house is at that dangerous liminal space between civilisation and wilderness.

- Oh no. There’s a marshy field a little further along. Marshes are creepy and dangerous places.

- Later we’re told of ‘the falling-down grand-stand in the old fairgrounds sticking up like a crazy skeletal tower, in the dark’.

Is there a word which means the opposite of gentrification? Urban blight, apparently. Or slumification. Whatever we call it, this part of town has been left to the poorest residents. Most have moved because of flood risk. This street is a metaphorical ravine. It lies in the path of floodwaters. The water (or the threat of water) ‘invades’.

Nearby, roads have been laid out, but plots haven’t been filled. A racetrack oval is ‘still marked out in the grass’. This is Alice Munro teaching us how to read the story: Look out for a palimpsestic version of the narrative (another story, just under the surface).

What is that other story? Even Eunie herself has another version of the real story — the story that plays out in the world of her imagination.

CHARACTERS IN “SPACESHIPS HAVE LANDED”

EUNIE MORGAN

Eunie had always been a peculiar sight, tall for her age, with sharp, narrow shoulders, a whitish-blond crest of fuzzy hair sticking up at the crown of her head, a cocksure expression and a long, heavy jaw. That jaw gave a thickness to the lower part of her face that seemed reflected in the phlegmy growl of her voice. When she was younger none of that had mattered —her own conviction, that everything about her was proper had daunted many. But now she was five feet nine or ten, drab and mannish in her slacks and bandannas, with big feet in what looked like men’s shoes, a hectoring voice and an ungainly walk —she had gone right from being a child to being a character.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Because of the diminutive name, and her habit of peeing on grass rather than walking as far as the outhouse, at first I imagined a young girl. But then, who is “the old woman”? Does this household have a grandmother? No, “the old woman is Eunie’s mother, and Eunie is in fact grown. She rides a bicycle to work. She’s been working at the glove factory since the age of fifteen — a decision she would’ve made on her own, without parental advice. She was always allowed to help herself to molasses and bread, but basically brought herself up in a household where she was a late addition to a couple who’d already reached middle-age and were never in the frame of mind to bring up a child.

Eunie is an only child, and a late one, surprising her mother by crowning when Mother believed she was going through menopause, not pregnant.

Once she started earning money she bought a bicycle and a radio. She became interested in crime news and natural disasters.

EUNIE’S MOTHER

“The old woman”. A simple soul who knows how babies are made, but who manages to avoid being saddled with one until middle-age, when one pops up to surprise her, almost an immaculate conception. By this stage she’s too old/set-in-her-ways to make a good job of being a mother. She basically leaves the girl to bring herself up. She has a combative but manageable relationship with her husband.

EUNIE’S FATHER

We are told he does not like receiving information from anyone at any time, and we observe from the scene Munro paints that his wife knows how to work him. Mother allows Father to take control of the missing-daughter situation by handing him the torch. (Like how some women let their husbands drive everywhere, but then tell the husbands where to go.)

RHEA

Eunie’s childhood playmate. Together they call themselves the Toms. The Toms are agender. Tom, to them, simply means someone who is brave and goes on adventures.

Rhea and Eunie are not friends in any caring sort of way. They don’t look out for one another.

Rhea has a lot more parental constraints on her freedom. By comparison, Eunie can do anything she liked.

Although she lives near the cottages in the poorest street in town, her family are chicken farmers and consider themselves a separate class of people from the likes of Eunie and the Monks, who run the bootlegger’s.

THE BANNERSHEES

Like the kids in Bridge to Terabithia, Eunie and Rhea create an imaginative, supernatural layer on top of their real world. The Bannershees are the creatures which lurk along the river. (robbers, Germans or skeletons). The Germans detail reminds us that in 1953, WW2 was recent in everyone’s mind.

Sometimes Eunie and Rhea have to play their own baddies. They themselves become the Bannershees and destroy whatever they’ve created out of mud. Imaginatively, these kids are amorphous. They have agender as well as amoral, completely flexible, trying out all of the roles.

THE MCKAYS

Although Eunie and Rhea torture imaginary creatures most of the time, occasionally they tried to torture real children, the McKays who lived for a short time in one of the river houses. They wanted some kids who wouldn’t mind being tied up and thrashed with cattails, but the McKays weren’t interested in filling that role.

BILLY DOUD

Whereas Eunie at the bottom of the social hierarchy, Billy Doud is at the top.

Tall and pale, cool and clean — he himself might have been carved of soap. A high curved forehead, temples already bare, hair with a glint of tinsel, sleepy ivory eyelids. He was through college at last, he was twenty-four years old and home to learn the piano-factory business.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

When Rhea has left school and is working in a shop, he comes in to buy rubber boots. They start dating.

As a privileged white boy, he has come home from college having spent his years away drinking in the 1950s equivalent of modern frat boy life. This is a privileged cohort of men who, unlike their fathers and uncles, avoided being sent to war. The world looked bright to them and, let’s face it, the rest of the 20th century panned out nicely for (most, cishet) men like Billy Doud. (Munro will surprise us with regards to Billy, though.)

Except Billy Doud isn’t the horny frat boy we might expect. He is keeping his feelings for Rhea in check. Or else he doesn’t have such feelings at all. Billy is more interested in impressing his friend Wayne than ‘parking’ with Rhea.

Rhea’s younger brothers take the mick, imitating his upper-class manners. They call him Silly Billy, Silly Putty, then Putty.

Rhea’s father doesn’t think much of Billy Doud, but the feelings aren’t mutual:

Billy Doud said how much he admired Rhea’s father. Men like your father, he said. Who work so hard. Just to get along. And never expect any different. And are so decent, and even-tempered, and kindhearted. The world owes a lot to men like that.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Of course, the reader sees what Rhea’s working-class father can clearly see from this statement: Without the workers like himself, the likes of the Douds wouldn’t be wealthy. Such is capitalism. Rhea is blinded to it by attraction, but such praise is patronising.

THE TARTAR

Billy Doud’s mother. (This is her nickname.) Tartar is an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups.

WAYNE

He was one of those people who make far more of an impression than their size, or their looks, or anything about them, warrants. He was not very tall, and his compact body might have been pudgy in childhood—it might get pudgy again. He had a square face, rather pale except for the bluish shadow of the beard that wounded Lucille. His black hair was very straight and fine, and often flopped over his forehead.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Billy’s friend, a minister’s son. He has told Billy, who passed on to Rhea, that he is interested in Lucille because she makes good, solid, housewife material. He doesn’t think she’s much to look at.

(This information must make Rhea wonder what’s wrong with her, since Wayne ravishes Lucille anyway, and Rhea is not getting ravished by Billy.)

Wayne and Billy are different with each other when they have their masculinity to maintain:

He and Billy hadn’t greeted each other as they usually did, with a growl and punch in the air. They were cautious and reserved in front of these older men.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

LUCILLE

Wayne’s girlfriend.

Lucille was a thin, faired-haired girl with a finicky stomach, irregular periods and sensitive skin. The vagaries of her body fascinated her, and she treated it as if it was a balky valuable pet. She always carried baby oil in her purse and patted it onto her face which would have been savaged, a little while ago, by Wayne’s bristles. The car smelled of baby oil and there was another smell under that, like bread dough.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

MRS. MONK

Her dark, graying hair was coiled up at the back of her head, and she didn’t wear makeup. She had kept a slender figure, as not many women did in Carstairs. Her clothes were neat and plain, not particularly youthful but not what Rhea thought of as housewifely. She wore a checked skirt tonight and a short-sleeved yellow blouse. Her expression was always the same —not hostile, but grave and preoccupied, as if she had a familiar weight of griefs and worries.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

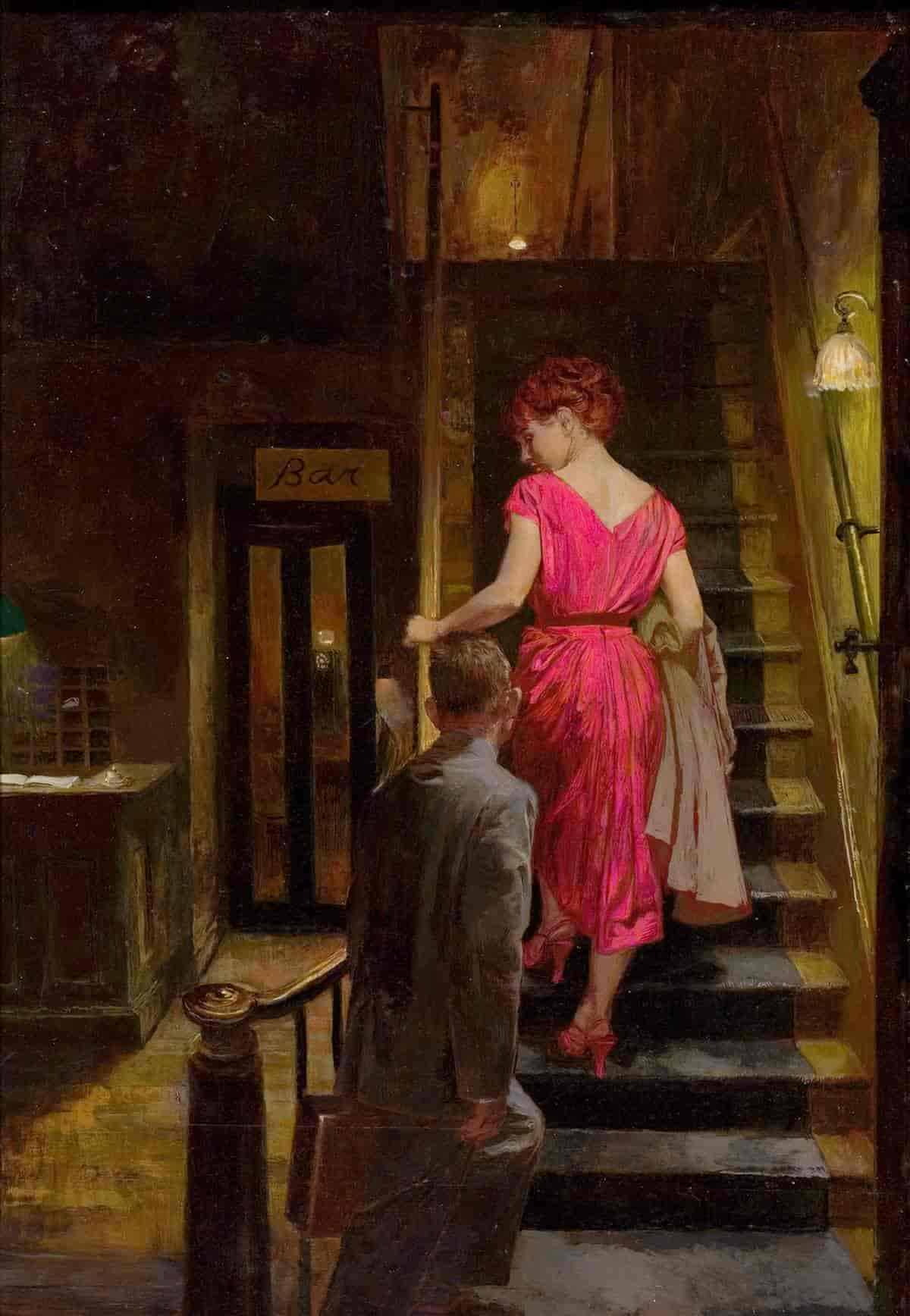

The landlady of Monk’s, the bootlegger’s establishment a few houses down from Eunie. The walls show evidence of the flood that happened years ago. This is an unheimlich establishment, and seedy.

Barren tidiness, dark green blinds pulled down to the window sills. A tin

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

curtain in one corner, probably concealing an old dumbwaiter.

When her wealthy customer Billy introduces his girlfriend, Rhea, Mrs Monk is entirely uninterested. Rhea understands that Billy thinks all poor people are the same, and that therefore these two poor women would have much in common.

Bootlegging in a 1950s setting had me confused. After all, hadn’t Prohibition ended by then? From what I can work out, ‘bootlegger’s’ is a residual term for a down-market drinking establishment which was once a bootlegger’s, before Prohibition was repealed.

Incidentally, despite the repeal, North American Protestants were behind a huge 1950s movement against alcohol consumption, believing it to be driving a huge proportion of crime. (Some also associated drinking with Catholicism, and hated alcohol for that reason.)

Despite Mrs. Monk’s aloofness, she provides a model of womanhood which Rhea has no access to in anyone else. Perhaps Rhea doesn’t have to be a housewife and only a housewife? If she doesn’t mind keeping her own lower class, she could be a business woman like Mrs. Monk.

Mrs. Monk was to Rhea the most interesting person in the room. Her legs were bare, but she wore high heels. They were tapping all the time on the floorboards.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

But then Rhea, who is sexually naïve, understands that Mrs. Monk is also selling sex. She imagines Mrs. Monk servicing the men with the same cool, detached attitude she displays in the main area of the pub. Rhea finds this exciting to think about.

Now we’re getting to the palimpsest of this town — the things that happen below the surface. Rhea only knows this happens because of town rumours. The signs are there, but only for those who choose to look.

ANALYSIS OF “SPACESHIPS HAVE LANDED”

EUNIE’S CHILDHOOD

After Eunie’s parents give up the early morning search for their only daughter, readers get a flashback to Eunie as a child. Via the viewpoint of Eunie’s playmate, Rhea, we learn that Eunie basically brought herself up. Her parents were busy and inattentive. We also learn that Rhea doesn’t even consider Eunie a good friend. They never cared for each other in an emotional way or shared secrets. An irritating thing about Eunie: She tells outlandish stories, but refuses to let Rhea know whether these stories really happened or if she’s still living in the childhood world of their imagination. It is here that I get a sense of where the title may have come from. I can see how Eunie may make up a story about alien invasion, telling Rhea it as if she heard it on the radio.

RHEA AND EUNIE AS TEENS

When they reach adolescence, Rhea understands Eunie to be a drain on her own social capital, and wants nothing to do with her. Alice Munro describes Eunie as tall and ‘mannish’ in both looks and dress. Today we might call such a character genderqueer or gender non-conforming. (We can’t know what’s inside Eunie’s head because the narration doesn’t let us in.) In contrast to Eunie, Rhea is propelled upwards in social standing when she starts dating the most eligible bachelor in town—the 24-year-old son of the owners of the piano factory.

Basically, when Eunie disappears at the start of the story, we know she was utterly alone in life.

The story opened with the missing Eunie, but the story switches firmly to Rhea.

What is Monk’s?

She is sitting in the corner at Monk’s. Mentioned in the very first paragraph, it is mentioned again when Billy and Wayne disappear into it, leaving their girlfriends outside alone. This is the bootlegger’s house, ‘a bare, narrow wooden house soiled halfway up the walls by the periodic flooding of the river.’ Billy Doud, despite being rich, is drawn to this place. He plays cards there (and we can assume, gambles). Rhea grew up near here, on a chicken farm. So did Billy, though he is of the merchant class, not of the working class (a phrase only Billy uses, and which Rhea has only read in books). Rhea feels uncomfortable in this masculine place, and in general, with her sudden entry into Billy Doud’s wealthy, upper-class world. There’s nowhere she feels comfortable anymore.

Turns out Rhea is as alone and lost as Eunie. The two were never close friends, and they share aloneness in common. (Rhea assumes Eunie has fallen in with the loud, brash women from the glove factory. She is even alone in her feeling-aloneness.)

Glove. Eunie worked at the (hand) glove factory. But this story contains another use of this word. When Wayne’s girl asks Eunie if she’s getting used to ‘it’, naïve and inexperienced Eunie has no idea what she’s talking about. Lucille thinks sex will be better after she’s married because they won’t have to use a ‘glove’. Neither of these girls is having a good time with their boyfriends, we can deduce. Whereas Billy is avoidant, Wayne is slapdash and goal-focused.

The contemporary reader may already, at this point, assume these boys are gay. Eunie didn’t know what a condom is. She definitely wouldn’t know about human variation in orientation and attraction. But we can’t jump to this conclusion yet. It’s clear that Billy is repulsed by women, by their bodies. In misogynistic cultures, young men are far more interested in each other than in women, regardless of sexual attraction. To men like Billy and Wayne, women are for sex and wife-ing. And before homosexuality became mainstream in the dominant culture, men didn’t worry so much about not appearing gay. No one was suspecting them of it because it didn’t cross anyone’s minds. Michel Foucault wrote about a kind of culturally shared ignorance around gay matters. To simply know about gay people might make you gay, or at least stigmatised.

Without an attentive boyfriend, Rhea lives a sexual fantasy via Mrs. Monk, spurred by the rumours about her, which she later comes to believe are false. We’re not told at this point why Rhea came to believe those rumours are false. Perhaps she has an epiphany about how women are spoken about by men in the binary wife-wh0re dichotomy.

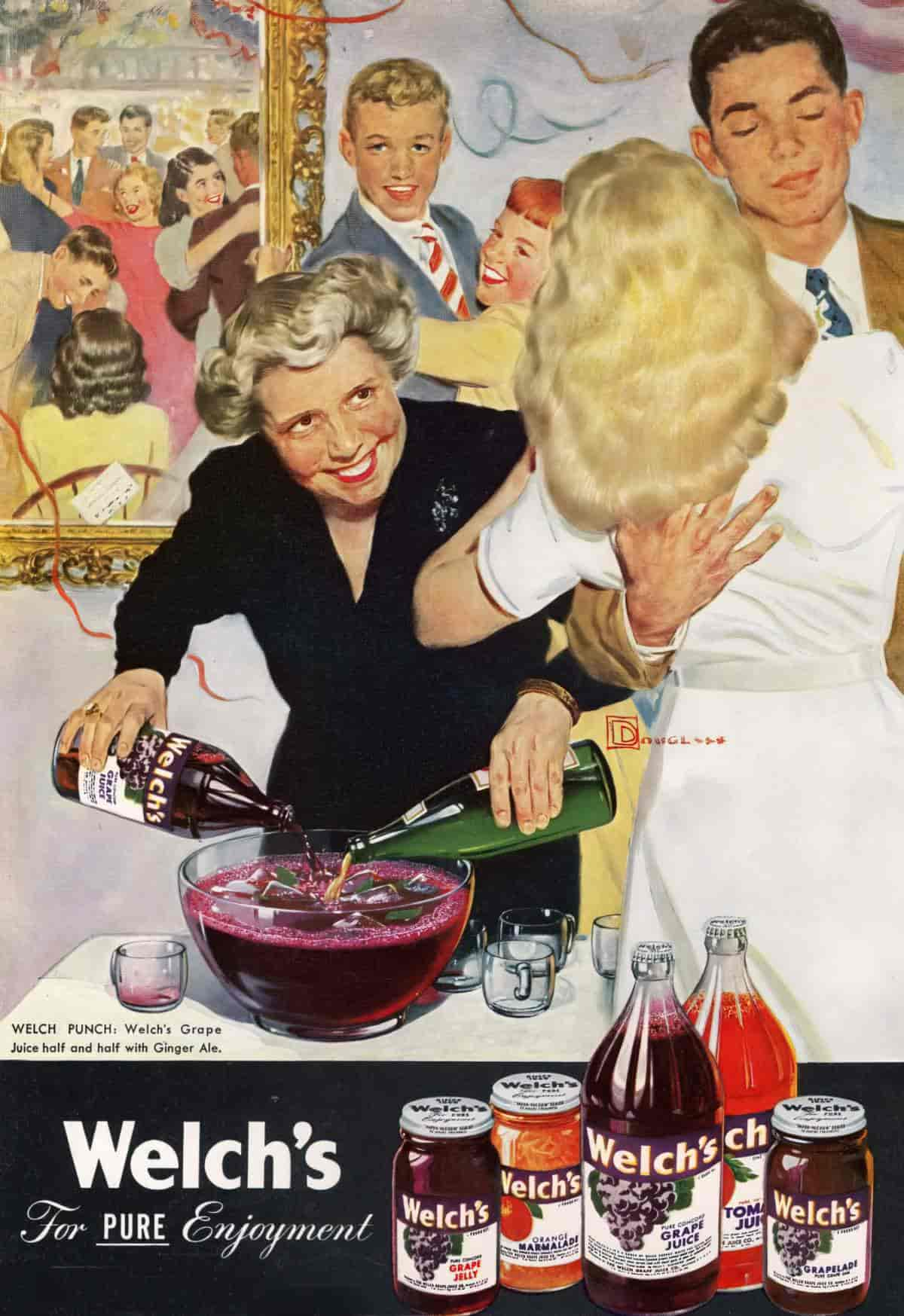

Oh dear. At Monk’s, Wayne spikes Rhea’s drink. At least, that’s what we’d call it these days. The most common form of spiking is not, in fact, Rohypnol or some other drug, but simply involves plying someone with stronger alcoholic content than they’re expecting. Rhea has no word for ‘spiking’, so she can’t see how wrong it is.

In any case, the tradition of party punch (in which no one knows the alcoholic content) enables a culture of spiking. Consequences are worse for infrequent drinkers, small people and women.

She drinks the strong-smelling drink ‘Coke’ Wayne gives her—to be polite—and also to show Wayne that ‘he had not flummoxed her’.

Ah, young women do expend a lot of effort proving to men they have not been ‘flummoxed’ by them. The #metoo movement was a whole lifetime too late for these young women, and the pressure to look cool and level-headed, like you belong in male dominated spaces hasn’t exactly gone away.

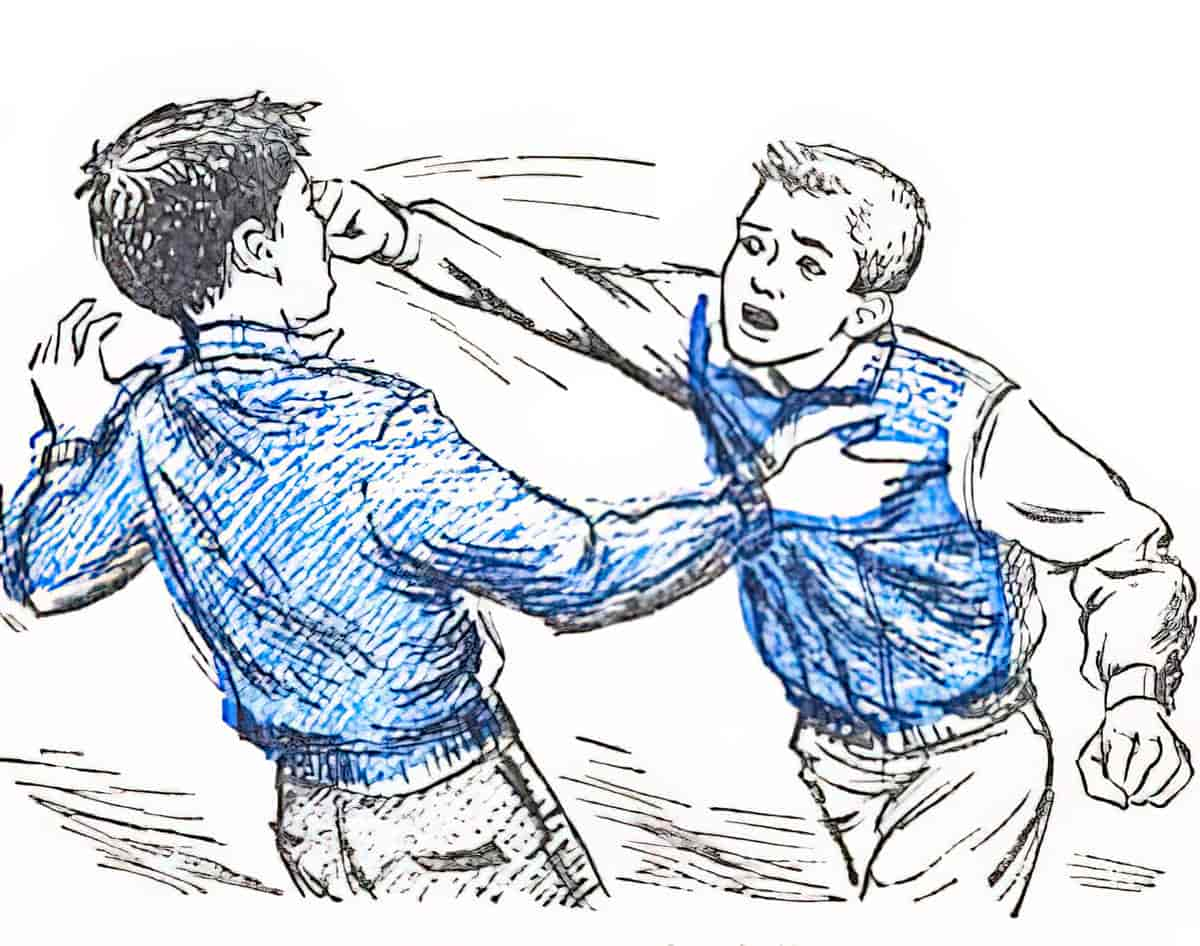

Alice Munro makes the most excellent job of creeping me out by Wayne, who is deliberately making Rhea uncomfortable. I really want to flip his table.

He’s using a tactic out of the Pick-up Artist’s Playbook. “Oh, sorry, am I making you uncomfortable?” He understands full well that Rhea is under pressure to keep her cool in this space which has been set up to alienate her.

“Yeast. Isn’t that another thing girls get? Am I embarrassing you? I should be a gentleman and get you another drink.”

Wayne in “Spaceships Have Landed”

This is where ‘negging’ leads to:

“I’d like to fvck you if you weren’t so ugly.”

Wayne in “Spaceships Have Landed”, as he assaults Rhea

For decades, a feminist tagline has been ‘Rape is not about sex. It’s about power.’ What is Wayne hoping to achieve? He aims to knock Rhea’s confidence, to keep her in her place, lower than him in the pecking order. Of course, inside the pub, Rhea stood up to him by telling him he clearly doesn’t like her boyfriend, Billy.

Wayne’s whispered insult has the desired effect:

She was not ugly. She knew she was not ugly.

How can you ever be sure, that you are not ugly?

But if she was ugly, would Billy Doud have gone out with her in the first place?

Billy Doud prided himself on being kind.

But Wayne was very drunk when he said that.

Drunkards speak truth.

Rhea’s internal monologue, the morning after

It helps so much that young women now have access to words for these creeps and their tactics. I mean, it’s no inoculation, but just to have the words is a huge help when it comes to the post-processing.

Could this be what Alice Munro is getting at when she encourages readers to look for the palimpsestic layer of this story, first by mentioning the racetrack which is only just visible? Horrible things are happening to Rhea (and we can assume to Eunie as well), but Rhea is deeply lacking in basic knowledge about how the world works, about sex, about gender relations. She isn’t just lacking the words, she is lacking the very concepts.

There’s a word for this now, too. Hermeneutical injustice. Hermeneutical (‘interpretive’) injustice is when someone experiences injustice due to a lack of having the concept/words to describe it. (More on that here.)

But just because you lack the words and the concepts doesn’t mean you can’t understand it or see it, in some inchoate, un-utterable way. Rhea is smart. In some ways she knows what’s going on with these two boys.

Alice Munro tells readers in the very first paragraph that this story is set in the 1950s. It was published in the 1990s. This is a story about how different the 1950s was for young women compared to women coming of age in the post Second Wave Feminist movement of the 1970s. Of course, youth looks even more different now, in the 2020s. Yet it is still disturbingly familiar:

“Let him,” she said. “Let him,’ She turned off the light and stepped into the dark hall. Hands took charge of her at once, and she was guided and propelled out the back door.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

The sex positive movement has been great and necessary. But in service to the patriarchy, this movement has also (mis-)taught a generation of young women that female empowerment looks like having adventurous sex with as many people as possible.

Is this consent?

Alice Munro has painted the perfect scene of ambiguity:

- A boy spiked his friend’s girlfriend’s drink.

- The girl smelled alcohol and drank it anyway, knowing the drink had been spiked.

- But she didn’t ask for the alcohol and had no idea how much it had been spiked.

- An entire misogynistic culture—personified by Wayne—has conspired to teach this young woman that if she didn’t show herself to be ‘unflummoxable’, she’d leave herself vulnerable to predation.

- In this wish to show her own toughness (a dynamic we easily recognise in young men but less easily recognise in young women), she acts recklessly.

- Unsure of her own attraction and desire, she persuades herself in the bathroom mirror (while drunk) to let sex happen.

- At no stage is there any spoken agreement about what would happen when she emerges from the bathroom.

- If she hadn’t told herself to let sex happen, would Wayne have not grabbed her?

- Added to the calculus of decision making: A culture of compulsory (hetero)sexuality, in which young people (especially) feel disposable and unwanted if they’re not having sex. (Rhea’s boyfriend has shown her that he’s not interested in her.)

People weren’t talking in terms of ‘consent’ in those days. There was no black-or-white discussion in which sex is either enthusiastically consented to or else assault. There was another phrase, which encompassed gray areas such as these: Rhea was “taken advantage of“.

She was getting a warning, too — something in the distance, not connected with what she and Wayne were doing. A troop of demons in the distance, trying to make themselves understood.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Rhea doesn’t have the guidance of a mother figure. Her own mother is in hospital for some unexplained reason. At home she only has a father and brothers, who have probably deemed her boyfriend substandard in the manly department, but believe Billy to be a protective forcefield to Rhea until such time as the penny drops and she moves on.

Consent is not a binary yes or no. Consent is a spectrum, and Mrs. Monk knows this. It is Mrs. Monk who helps Rhea after she vomits. It’s Mrs. Monk who has seen it all, and tells Wayne to scat.

Rhea imagines what it would be like to visit her mother in hospital and tell her what happened.

The word fvck was what would incense her, more than the word ugly. She would miss the point entirely.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Whatever the hermeneutical injustice experienced by Rhea, her mother came of age in an even less enlightened time. For Rhea’s mother, it is easier to focus on an instance of foul language than to look any deeper. The palimpsestic layer is entirely invisible to her mother, who focuses on the word to describe the despicable act, not on the despicable act itself.

Rhea’s father’s reaction would be more complicated. He would blame Billy, for taking her into a place like Monk’s. Billy, Billy’s sort of friends. He would be angry about the fvck part but really he would be ashamed of Rhea. He would be forever ashamed that a man had called her ugly.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Any shame experienced by Rhea’s father speaks to a culture in which women (wives, girlfriends and daughters) are the property of men. Ergo, to rape a woman was to commit an offence against the man who owned her, not against the woman herself. (The same held true for slaves.)

This aspect of law had changed by the 1950s. Women were by law (somewhat) independent humans. but the attitudes behind it had not. In some states of 1950s USA, a white woman having consensual sex with a black man was considered rape. Black men were considered rapists; women were not assumed to know their own mind (treated as either children or adults, in service to the gender hierarchy we call patriarchy.)

In the 1950s, what happened to Rhea would not have been decoded as rape. Rape happened in dark alleys, when vulnerable women were pounced on by boogeymen strangers (and Black men). It wasn’t until the 1980s that date or acquaintance rape first gained acknowledgment. Alice Munro wrote “Spaceships Have Landed” in the wake of that movement, for an audience who had a (somewhat) better idea of what rape can look like.

It took several decades for all the states of the USA to make marital rape a crime. South Dakota had been early, making it illegal for men to rape their wives in 1975. North Carolina was the last, in 1993, the year before this story was published. For context, England and Wales updated their law in 1991, Canada in 1983, Ireland in 1990, Scotland in 1989, Australian states and territories between 1981 and 1992, New Zealand in 1986. So, in comparison to some parts of the USA, Canada had this conversation a bit earlier.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER RHEA IS ASSAULTED?

Rhea no longer feels safe in the world.

A car hooted from the road. Somebody who knew her, or just a man going by? She wanted to get out of sight, so she cut across the field that the chickens had picked clean and paved slick with their droppings.

Alice Munro, Spaceships Have Landed

Even when she climbs the childhood treehouse in her backyard, she sees her own brothers in a new light. They’ve cut a hole in the leafy branches, ‘for spying’. She feels surveilled by men, and her brothers are also men in the making.

Rhea uses this spy hole to check on Wayne and Billy as they walk into church. She has learned that, from now on, she must be hypervigilant. She has no one to protect her aside from women with no social standing, like Mrs. Monk.

Alice Munro reminds us of the significance of that old racetrack, and here’s hoping readers now have a handle on its metaphorical meaning:

In another direction, she could see flashes of the river and a pan of the old fairgrounds. It was easy from there to make out where the racetrack used to go round, in the long grass.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

RHEA SEES EUNIE

This story kicked off with the disappearance of a 19-year-old woman. Both of these young women have been let down by their communities and the culture which drives them.

Eunie’s form of neglect was more obvious. Her parents never wanted her, never cared where she was.

Rhea had a different kind of childhood. As the only daughter of chicken farmers, she was well cared for, at least by 1950s standards. Her parents gave her curfews, knew where she was. Yet Rhea, too, was neglected. Despite being smart, layer upon layer of hermeneutical injustices conspired to ‘put Rhea in her place’ as a young woman testing out her ability to enter male dominated spaces and share her own opinions.

From her spot in the treehouse, Rhea spots Eunie on the racetrack, in her pale pink pyjamas, walking until the track veers off ‘where the riverbank path used to be’. Emphasis on ‘used to be’. The path doesn’t exist. Rather, Rhea knows it to be there. It’s a path these young women walk without anyone else seeing the path. Metaphor upon metaphor, see?

Rhea has no idea Eunie went missing and, until now, readers didn’t know that Rhea’s sexual assault and Eunie’s disappearance happened on the same night. Time converges.

Rhea thinks Eunie looks like an angel, or a snowball, or like ‘threads of ice preserved from winter, and she would want to mash her face against it, to get cool’.

Until now, Rhea has failed to see that she and Eunie have a single thing in common apart from the imaginative games they shared as children. Now it is clear to her that, as young women growing up in this town, they share in common an experience no one else can possibly relate to. They are each alone in this town, and see things no one else can.

[Rhea] remembered the hot grass and garlic and the jumping- out-of-your-skin feeling, when they were turning into Toms.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

As kids, these girls were able to shed the strictures of their gender and imagine a freer life. Once they were past puberty, neither of them is immune from the constraints imposed upon femme-coded people, whether pretty like Rhea (of course she’s pretty—she was picked by a boy who is only interested in pretty), or ‘mannish’ like Eunie. There’s no escaping gender.

RHEA PHONES HER RAPIST

Next, Rhea phones the boy who assaulted her last night. In rape trials, acts such as this have been used as evidence against the victim. Why would a victim want anything to do with her rapist? In fact, this is a very common thing to happen, as the victim tries to process and reconcile what happened to her. (Jon Krakauer illuminated this in his book Missoula.)

Of course, Wayne calls Rhea crazy for suggesting they both leave town. Calling a woman crazy is yet another red flag. Sigh.

WHAT HAPPENED TO EUNIE?

The narrative camera switches back to Eunie, who returns to her home kitchen. Alice Munro returns to the metaphor of the path:

It was a surprise to Eunie to find the riverbank path not clear as she was expecting it it be, but all grown up with brambles.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Whereas Rhea had an epiphany last night, and now understands exactly how vulnerable and isolated she is in this town, Eunie is less enlightened than she was before.

Eunie’s father had phoned Billy’s father, Mr. Doud (among other people). As the rich man in the town, Mr. Doud is the person people turn to in times of need, and Eunie’s father worked for Mr. Doud when he was young.

Eunie’s mother says something cryptic: “You mean the one that’s dead,” said Eunie’s mother. “What if you get her?”

In any case, Billy Doud answers the phone. He gives Eunie the rapt attention she requires.

So do many people. Because Eunie says she was abducted that night. Although she doesn’t use the word ‘spaceship’, others take control of the narrative and turn it into that.

A skeptical reader will more likely read this incident as the first clear sign of a serious mental disorder such as schizophrenia, which tends to appear around Eunie’s age.

Significantly for this short story, Eunie’s psychosis is accepted by many as fact. She gets in the paper; she has a book written about her experience.

The town believes Eunie’s alien abduction narrative, but Rhea (and the reader) knows they would never believe Eunie if she told them she’d been sexually assaulted.

What these two young women have in common: Other people take over the narrative. One story is blown up, whereas the other is blown away. Rhea doesn’t have the words for it. Wayne, her assaulter, is left thinking the only thing he did wrong was to call her ugly.

THE SUCKERPUNCH ENDING

Alice Munro tells us that Rhea and Billy left town, drove to Calgary and got married.

Like the pub incident, this marriage isn’t done with full consent. Rhea only wants to live with someone she knows in this strange city, but a man cannot rent a place with a woman unless the pair are married. The spectrum of consent continues, in which major life decisions are impacted by this entire suite of invisible, oft-unspoken pressures and constraints.

In case we haven’t picked up that this entire story concerns who is believed, who is disbelieved, Alice Munro tells us what happens to Wayne. He enjoys a successful career as a journalist:

Wayne left the paper and went into television. For years you might see him on the late news, sometimes in rain or snow on Parliament Hill, delivering some rumor or piece of information. Later he traveled to foreign cities and did the same thing there, and still later he got to be one of the people who sit indoors and discuss what the news means and who is telling lies.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

We are told that Eunie (presumably stuck in her childhood town forever) became very fond of television.

As Alice Munro is inclined to do, we meet Rhea again in the present. She’s an older woman now, and visits Carstairs. In the graveyard, she sees the name Lucille Flagg (Wayne’s first fiancée) on a gravestone. But Lucille isn’t died. Lucille married someone else, and that guy has died. She’s had her own name etched into the stone in preparation for her own death.

Munro underscores that this story is also about the invisible bonds between women:

Rhea remembers the hats and rosebuds, and feels a tenderness for Lucille that cannot ever be returned.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Another surprise:

At this time Rhea and Wayne have lived together for far more than half their lives. They have had three children, and between them, counting everything, five times as many lovers.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

Is Rhea happy? Has she lived her entire life in a series of subpar relationships? She says to herself in the graveyard, “I can’t get used to it.” Has she spent her entire life proving to men that she’s ‘unflummoxable’?

Recall that when Lucille asked her this question, she was asking about sex. It’s unclear in this new setting whether Rhea is thinking about that, or about the realities of getting old. She’s likely thinking about all of it.

Rhea and Wayne meet up with the Douds for a drive. (We learn at this point that Billy has married somebody.) The flood houses are all gone due to proper reclassification as a floodplain. The reader might wonder at this point where Eunie is living.

Then we get our answer. Eunie has married Billy:

He pats his wife on her broad back, responding to a low grumble that the others haven’t heard. He tells her they’ll be going home in a minute, she won’t miss the show she watches every afternoon.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

But Eunie hasn’t gone up in socioeconomic class. Nope, Billy has gone down. ‘After Billy’s mother died, problems multiplied and Billy sold out.’

I suspected schizophrenia for Eunie (as Munro obviously meant me to), and now Alice Munro provides the word on the page, though she doesn’t confirm that it applies to Eunie. She only wishes to put it in our heads, I’d assume:

Billy went to Toronto and got a job, which Rhea’s father said had something to do with schizophrenics or drug addicts or Christianity.

Alice Munro, “Spaceships Have Landed”

It’s fully in keeping with the theme of ‘half-knowing’ that Eunie is not, herself, said to have been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Rather, people know that schizophrenia is a thing that some people—unknown, distant people can have—but it’s a scary, unknowable thing, so you don’t know anyone with that. We see this in other stories by Alice Munro, for instance the daughter who may or may not have had childhood leukemia in “Moons of Jupiter”: ‘Nobody mentioned leukemia but I knew, of course, what they were looking for’. Nobody mentions sexual coercion. Nobody mentions the half-choice of getting married. Nobody mentions, nobody mentions…

The final paragraphs of this story confirm what we probably already suspect: The relationship between Billy and Eunie is not a sexual one. Once again, let’s not jump to the conclusion that Billy is gay. I decode this character as asexual. The asexuality of the Douds stands as juxtaposition to the (hyper)sexuality (1970s inspired polyamory?) of Wayne and Rhea.

Billy has found his family by offering kindness to those in need. Who is more in need than Eunie? And what does kindness look like? What does it mean to be married? What are the minimum requirements? The character of Billy is otherwise confounding. He is ultimately unknowable, perhaps because Young Billy is a quite different person from Old Man Billy. What looked like condescension towards people less fortunate than himself may have been genuine caring, after all. This only became apparent once he lost his own wealth privilege.

Why such juxtaposition between two very different couples? Billy and Eunie are hardly the pin-up poster for idealised romance. But as Munro showed us, nor are the Douds. How many women of the 1950s had first sexual experiences very much like Rhea’s, then married those men because the culture basically taught them that you marry the man you first have sex with?

WHAT ARE THE METAPHORICAL SPACESHIPS IN “SPACESHIPS HAVE LANDED”?

Of course there are no aliens in this Alice Munro short story. The spaceship is a metaphor. But what is the metaphor for?

Some ideas:

- As Rhea enters adolescence and adulthood, the world becomes increasingly alien to her, until she experiences a life-changing incident in the bootlegger’s and now she really feels alienated. The spaceship really lands.

- The 1950s was a big decade for UFO sightings in North America (including Canada, I assume). There are many reasons for this, but as even contemporary readers will know, part of the ‘abducted by aliens’ story involves someone’s body being invaded (probed) without their consent. A metaphor for rape.

- Alice Munro’s story investigates which stories we understand to be true, which to be false, and which to be ambiguous. Many North Americans in the 1950s probably had ambivalent ideas about whether UFOs had really been sighted. Sure, people say they’ve seen UFOs, and they may really think they did, but seems unlikely to me. Didn’t really happen. An analogue for date rape. Women said it was happening, but people didn’t really think it was. It was too confronting to believe upstanding young men such as the minister’s son would do a thing like that. If you were to believe that, you’d believe anything, right? Safer to believe nothing at all.

- If young women of the 1950s were to report rape, even to their own parents, this did them no good. They may as well have told their parents they’d witnessed a spaceship landing. It was shameful to be involved in such a thing. To speak of a taboo meant you weren’t quite right in the head. Why would anyone share information that brings such shame upon them, and their whole family? That is evidence of craziness itself.

- Fast forward to the end of the story, and all four of the elderly main characters are at home with themselves. They’ve found their way in life. In this metaphor, the characters were ‘spaceships’ in their youth (confounded by their milieu, unmoored, unaware of how little they knew), and old age is a kind of ‘landing’.

SEE ALSO

UFO In Kushiro by Haruki Murakami is another short story in which the author makes use of a spaceship as metaphor.

Alice Munro wrote about interpersonal abuses and hierarchies before people had words to describe what they were experiencing. Munro wrote about the dynamics of coercive control in “Queenie“, long before the culture had the phrase ‘coercive control’. Alice Munro published “Queenie” in a 2001 collection. The term ‘coercive control’ was contemporised and popularized by Professor Evan Stark, sociologist and forensic social worker, in his 2007 book Coercive Control: The Entrapment of Women in Personal Life.♦