**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You is a short story by Alice Munro, and opens Munro’s 1974 same-named collection. Two elderly sisters live together in a small tourist town somewhere near a lake in Ontario.

“SOMETHING I’VE BEEN MEANING TO TELL YOU” IN A NUTSHELL

Although nothing alike on the surface, “Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You” reminds me of a lesser-known modernist short story by Katherine Mansfield: “Psychology“.

In both stories, the main female character lives a sexually and romantically unfulfilled life, but in both cases she learns a workaround for herself. I’ll leave you to read Mansfield’s story if you haven’t already, but will assume you’ve already read Munro’s:

Et is four years younger than Char.

Unmarried sister Et lives a romantic life wholly inside her imagination. She imagines herself partnered with a man from the sisters’ youth who subsequently left town. In contrast, her more beautiful sister Char got married to Arthur, Et’s high school history teacher. Char does not love Arthur, who is a nerdy type. Readers never meet him when he is young. By the time we see him in a scene he is old and in poor health.

Readers never learn the exact nature of Char and Blaikie’s relationship before he left Char for an older woman in the summer of 1918, perhaps because Et herself doesn’t know, perhaps because Et cannot bring herself to put it on the page. She saw them together once, and Char looked ‘lost’, even more lost than the sisters’ dead brother Sandy, who drowned as a child.

When Blaikie left, Char drank some household cleaning product which didn’t kill her.

And now the man from Et’s youth is back. Blaikie Noble has moved back to town to drive tour buses after thirty years away. Before leaving he’d been seeing Et’s beautiful sister Char for a while, then left town to marry an older woman. He’s been widowed twice in his absence.

The characters are all in their autumn years now. A different sort of writer might have Et partner up with her old flame and they’d live together happily until they die. That’s not what happens. Not quite.

When her married sister dies, Et spends her old age in happy companionship with the sister’s husband instead.

Women who live inside their heads as a means of escape is a preoccupation across the corpus of Munro’s work, and also across Mansfield’s. Et reminds me of Mansfield’s Beryl Fairchild from her “At the Bay” stories.

Also like a Mansfield short story, the reader never learns the “something” from the title. Readers are left to fill in that narrative gap for ourselves.

So what is meant by that title? Who means to tell someone something, and what is it? Let’s take a look.

I don’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member.

Groucho Marx

“Why do you have to go off and live by yourself anyway?” [Arthur] scolded her. “You ought to come back and live with us.”

“Three’s a crowd.”

“It wouldn’t be for long. Some man is going to come along some day and fall hard.”

“If he was such a fool as to do that I’d never fall for him, so we’d be back where we started.”

“Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You”

SETTING

As the characters in this story get older, so too does the town. Once the site of a majestic hotel which attracted wealthy visitors, these days only retired couples and widows come. Wealthy outsiders have renovated most of the hotel, but an abandoned tennis court remains to serve as reminder of how irrepressibly the universe tends towards disorder.

Although the town is near a lake, there’s no longer any tourist industry around the water. Tourists must make their own way into town, suggesting that there was once a golden age in which wealthy tourists expected to be chaperoned from a boat which allowed passengers to disembark near the township.

The tourist attractions are these days minimal, and listed on the opening page of the story (on Blaikie’s laughable tour bus):

- Lakeshore tours

- Indian graves (reminding us of death and ghosts of past atrocities)

- Limestone gardens (a young marble formed from the consolidation of seashells and sediment)

- Millionaires mansion (abandoned)

CAST OF CHARACTERS

THE MEN

I’ll talk about the men first because there’s more to say about the women.

BLAIKIE NOBLE

Noble: belonging by rank to the aristocracy

We don’t know which female name ‘Et’ is short for, but it’s likely short for a name which means noble (Eth, Etty and Ethel all contain the meaning of ‘noble’). This symbolically links the names of Et and Arthur, and thereby turns them into a couple (though it’s super subtle). Significantly, the link between Et and Blaikie Noble is all symbolism, no substance.

- Has come back to town at the beginning of summer after about 30 years away in touristy places like Florida and Banff

- A contemporary of Et and Char (previously the object of Et’s affection)

- White hair which used to be blond

- Wears light colours which makes him into another ghost (linking him to Char)

- Now runs a bus for tourists as both driver and guide with fictional stories concocted for entertainment

- Also works alongside another man as a gardener at the hotel where he lives in a small room above the kitchen

- His family used to own that hotel until the 1920s; after that it was used briefly as a wartime hospital

- Blaikie’s piecemeal work is a comedown compared to his status in ‘the old days’ in which he was a catch

- He’s had at least two wives in his absence from town, both dead

- “Nervy”

As the story opens, the elderly Et has just joined a seniors’ bus tour run by an old flame who has recently moved back to town. Blaikie Noble has invited Et along.

BLAIKIE AND WOMEN

Note Alice Munro’s choice of words to describe how Blaikie looks at the women: He gives them a ‘narrowing’ look. What does this mean? I take this to mean he fails to see their full humanity. He sees them as a type: elderly women in need of titillation, and he’s just the man to do it.

But Blaikie’s attitude towards women is complicated. Alice Munro writes ambivalence very well. He is able to see something good in each and every one. Munro uses the metaphor of a ruby on the ocean floor which he keenly dives down to retrieve.

- Et tells Arthur that Blaikie has found a woman even though she made that entire thing up;

- We’ve already seen Blaikie concoct stories for the tourists.

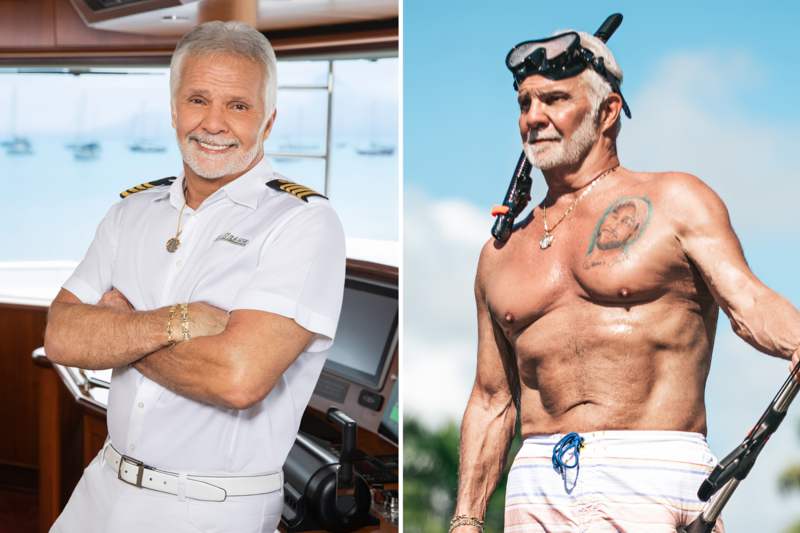

He is popular with the elderly ladies. I imagine he’s handsome in a Captain Lee kind of way:

Like any able-bodied man in a group of straight widows, Blaikie is naturally popular. He knows what these ladies need: to be guided by a man for a little while. The tourist destinations are very much secondary, though Et worries that his bullsh*t stories and supernatural historical details might fool them. These elderly women simply need a few hours of being guided by a man, and Blaikie steps up to the plate.

But Et does not appreciate her old flame touching all these other old ladies. “I’m not a tourist,” she reminds him. She has lived in this town her whole life and knows there was no woman who poisoned her husband in the abandoned house down the road.

BLAIKIE AND ET

The pair are symbolically linked by name, but how else are they linked? As it turns out, both live very much in their heads. Both are able to dive deep into a person and find a ruby there. Both concoct stories which aren’t true, and in a harmless but vaguely unseemly way, both Blaikie and Et bring others in on their own private stories.

ARTHUR (CHAR’S HUSBAND)

- a history teacher before retirement

- now has various health issues which prevent him from traveling

- very good at book learning, strong on detail and picking patterns

- not a practical person

- does not adhere to the rules of hegemonic masculinity

- was passed over for the promotion from classroom teacher to principal, which he would have normally been handed on a plate had he come across as more stereotypically masculine (There was a dearth of men after the war, and men are seen as natural born leaders in female dominated professions.)

THE DESMONDS

ET DESMOND

- a talented seamstress, which makes her a ‘spinster’ in both senses of the word, linking her to witchcraft

- naturally slim but not beautiful

- wore her hair in braids when young

- a little harsh on people, with internalised misogyny

- has had to cut back on her sewing work due to poor eyesight in old age

- is prone to worrying (e.g. about brother-in-law Arthur’s health, even when her sister isn’t worried in the slightest)

CHAR

- Et’s sister, four years older

- Pale complexion (almost “like a ghost” as she has gotten older — an example of foreshadowing)

- The designated beautiful one

- Naturally plump but fashionably slim due to a lifelong eating disorder

- Prone to mental health issues

- Was once infatuated with Blaikie Noble who left town and married an older woman

- Married to Arthur, who she despises

SANDY (THEIR DEAD BROTHER)

The sisters have a “ghost” in their backstory: a brother who drowned as a child. Sandy had been three years younger than Et. Ghost characters reveal psychic wounds. What is the ghost character revealing in this one?

In considering these sisters, I’m thinking of other women from fiction. Often in a story with two sisters we’re shown the binary of a Good Sister and an Evil Sister. Sometimes the Good Sister is (problematically) depicted as blonde; the evil one dark-haired. Maybe you can think of examples right now.

In any case, readers are used to asking the question of fiction, perhaps subconsciously, Which of these women is the evil one? Subverting the expectation of the Good Dark binary in all female pairings, Alice Munro is not about to tell us.

ET AND CHAR’S LITERARY SISTERS

ET AND FRANKIE ADDAMS

We know that Alice Munro was influenced by Southern American writers such as Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, Katherine Anne Porter and Carson McCullers.

In A Member of the Wedding (1946) by Carson McCullers, 12-year-old Frankie Addams is utterly bored one summer in her hometown of Georgia — until she learns that her older brother will be getting married. She then inserts herself into the drama around his wedding. She gets a bit too involved, and means to follow him as he embarks upon married life with his new wife. Frankie even decides to call herself Jasmine, a hybrid name between her brother Jarvis and his bride Janice. Frankie buys herself an overly eye-catching dress which will take attention away from the bride. We know Frankie has found ‘herself’ when she reclaims the name Frances.

Some people call McCullers’ story Southern Gothic, other people consider it Southern Realism. Either way, I see similarities between Et and Frankie. Young Frankie briefly falls in love with a circumstance (her brother’s wedding) and this experience of being in love ushers her into adulthood. But Et seems to remain stuck in this adolescence. She, too, is in love with a ‘circumstance’ — the melodramatic, at times, life circumstance of her more beautiful older sister. Eventually, in old age, Et manages to slot into the dead sister’s life.

CHAR AND MERRICAT BLACKWOOD

We Have Always Lived In The Castle is a 1962 novel by American Gothic author Shirley Jackson, Jackson’s final work and masterpiece. Again we have a young woman who, six years earlier, as a 12-year-old girl who, lost most of the family to a dinner-table poisoning incident.

***spoiler alert***

Readers eventually learn it was Merricat who killed her parents, aunt and younger brother after poisoning the sugar bowl.

There’s something of Merricat Blackwood in Char, who Alice Munro arms with the Chekhov’s gun of an — ambiguously unopened — bottle of rat poison in Char’s cupboard, suggesting Char may be slowly poisoning her husband Arthur, and keeping him in chronic ill-health. Readers might fill in the gap that this terrible act is due to factitious disorder (formerly known as Munchausen’s by proxy), or perhaps Char hated Arthur because he could never be the real love of her life, Blaikie Noble.

Critic Jonathan Lethem said of Shirley Jackson that Jackson had the ability create “a vast intimacy with everyday evil”, and I’d say the same of this Alice Munro short story. We’re dealing with some kind of everyday evil in “Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You”. Even the title sounds Jackson-esque.

ET AND CHAR AND ANNIE WILKES

Might Munro’s Et and Char Desmond each be an Annie Wilkes archetype, à la Stephen King’s novel Misery, portrayed by Kathy Bates in the 1990 film adaptation? Readers of Munro’s short story are left wondering why Char suddenly dies, even though it’s always been Arthur in ill-health, and even though that’s how death often works. (Some people live in ill-health for years, others die without warning; you never know.)

With the recent British conviction of notorious nurse and baby killer Lucy Letby, there has been talk about why normal-seeming people who go into the so-called caring professions can sometimes turn into killers. Although female serial killers are rare, the ones who do kill multiple times tend to be found in hospital or caregiving settings. Aside from Lucy Letby history has revealed woman serial killers such as:

- Amy Archer-Giligan (early 1900s), who ran a Connecticut nursing home. Investigators found she used arsenic to poison numerous elderly clients — several of whom she married — after insuring them or persuading them to name her the beneficiary of their wills.

- Linda Hazzard (1910s): a quack doctor in Washington state, was responsible for the deaths of at least 15 patients by starving them during her fasting treatments.

- Genene Jones (1980s): Genene Jones, a licensed vocational nurse in Texas, was responsible for the deaths of numerous infants and children under her care by administering lethal injections. She seemed to get a kick out of putting small children in danger of death.

- Beverley Allitt (1991): a nurse in the UK, murdered four children and harmed several others by injecting them with insulin, causing their deaths or severe harm.

- Kristen Gilbert (1996): a nurse in Massachusetts, was convicted of killing four patients by injecting them with lethal doses of epinephrine. Prosecutors had argued that she wanted to attract attention, especially from her lover, a hospital security guard.

- Mary Beth Tinning (1972-1985): smothered nine of her children in New York by suffocating them. She was not a nurse but worked in healthcare settings.

- Gwendolyn Graham (1987-1988): a nursing assistant in Michigan, and her partner, Catherine Wood, murdered elderly patients in a care facility in a lover’s pact, seemingly for their own private entertainment.

- Christine Malevre (1997-2003): a French nurse who euthanized terminally ill patients without their consent, leading to her conviction for murder.

- Jane Toppan (1885-1901): a nurse in Massachusetts, confessed to murdering over 30 patients by administering lethal doses of medications. Apparently her goal was to murder more people than any other woman in history.

So it would not be breaching realism for Alice Munro to have created a woman ‘caregiver’ who is also a murderer.

CLOSE READING OF “SOMETHING I’VE BEEN MEANING TO TELL YOU”

HOW DID ARTHUR DIE?

Which sister was it? Neither? We’ll never know. Alice Munro does not give us hermeneutical closure.

- POSSIBILITY ONE: Char was poisoning Arthur over many years. Why this is believable: She once tried to poison her own self. If someone can get themselves o the point of ingestion (regardless of efficacy), this suggests that same person might also find it within themselves to poison someone close to them. There’s also the ambiguity around Char’s vomiting. I read this as bulimia, but in a fictional story? Might we also parse this character detail as some kind of longterm interest in the relationship between ingestion/poison/ridding of perceived toxins? Might she be practising the ‘art of vomiting’ in case she should ever ingest something she gave her husband? Also, Alice Munro makes it clear that Char does not love Arthur. However, this opinion comes via the close third person narration of Et.

- POSSIBILITY TWO: Et poisoned Char. Why this is believable: She seems to be long-term infatuated with Char’s life, and by extension, in love with Char’s husband. If Et even suspected Char was poisoning Arthur, she may have felt like his saviour by killing Char by Char’s own (perceived) method. At the end of the story Et tells Arthur there’s ‘something I’ve been meaning to tell you’. Possibilities:

- “Char was trying to poison you all these years, Arthur.”

- “I killed Char for us, Arthur.”

- “I’ve always loved you, Arthur.”

- POSSIBILITY THREE: Arthur could have poisoned Char after discovering on his own what his wife was up to.

- POSSIBILITY FOUR: Char could have died of natural causes. The entire poisoning scenario is a fabrication on the part of a sister prone to fabulation.

THE HAUNTED HOUSE STORY-WITHIN-A-STORY

The haunted house on the tourist route, along with the possible poisoning plot, is another element which puts me in mind of a classic Shirley Jackson tale.

For the purposes of “Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You”, this “haunted” house and this murder by a woman of her husband says something about 1970s gender roles. In 1974, when this story was published, the Second Wave feminist movement was going gangbusters.

It used to be thought that women are incapable of murder. This was of course borne of sexism:

[If] women are treated as less capable in one regard – even one that involves horrible atrocities – it can extend to other realms, too. […] The fact that women can occupy the dual role of oppressor and oppressed is a reality that is still not fully understood.

Why it’s important to see women as capable … of terrible atrocities, November 21, 2020

In the decades since Munro’s story was published, the gender gap in violent crime has narrowed significantly, meaning that women have become more violent, at rates now approaching the violence of men. Some commentators put this down to the unintended downside of emancipation. Others offer a different take: That women’s economic wellbeing has not kept pace with men’s economic wellbeing. More women than men live in poverty (and with children). We know that anyone living in poverty is more prone to crime. In the 1990s, there was also much problematic talk around the extent to which PMS might factor into violent crimes exacted by women. There is now a body of research around the role of gender in sentencing rates. It may be the case that women are more likely to be sentenced than men for the same crimes, and then serve longer sentences. However, the research returns varied results depending on methodologies and where studies take place.

ET UNDERSTANDS THAT WOMEN ARE NOT GULLIBLE

When conducting his bus tours with an audience of elderly ladies, Blaikie is both ‘scornful and loving’ when the women naturally want to hear the details of the historic murder. (This ambivalence is how the reader will be left wondering what happened.)

As Char reassures Et, no one needs to worry that the old ladies will be ‘taken in’. These tourists are out for a day of entertainment and simply want to hear a story.

What does Et’s reaction say about Et? She is confident none of the women will be taken in by Blaikie’s murder story. Why? Because she herself concocts stories but is fully able to resist being taken in? Because for Et, stories and real life are different?

FAT, SCRAWNY, SILLY WOMEN

What does Et think of women, though? She understands that old women are not silly. She notes that Blaikie talks to all of the women, ‘no matter how fat or scrawny or silly’. (Subtext reading: You wouldn’t expect a man to take interest in a fat, scrawny or silly woman.) Is this a pessimistically clear-eyed view of how misogyny works? Or is Et’s internalised misogyny? Again, the reader can’t be sure about Et.

Expressed to readers via the narrative: When it comes to having a female body, there is no acceptable shape or size.

Regardless of how Et thinks, Char has fully internalised that misogynistic messaging and ruins her body in service of slimness. Large bodies and small bodies are both bad — women cannot win. The sisters exemplify the binary of dismissed female body shapes, with Et being naturally thin and Char clearly exhibiting the signs of what today would be understood as disordered eating, wanting to make herself disappear to the point of non-existence.

(It is entirely plausible that Char died by her own hand in the end, whether meaning to in the moment, or after many decades of semi-starvation.)

THE SUITABLY CONTRITE GHOST

Notice how Blaikie has told the old ladies a didactic story. He means to teach the ladies something. Rather than simply thrilling them with the crime story, at least some of which he concocted, Blaikie adds that the ghost of the wife haunts the house, not because she is scary in any way, but because she regrets what she has done to the husband. “Don’t kill your husbands ladies, or you’ll regret it. You’ll be stuck in an old house forever alone.”

Blaikie can’t bear the thought of a woman murdering a man without consequence. As a man himself, that’s far too uncomfortable for him, when the stark reality is that it is instead overwhelmingly men who murder women in every country around the world — a story so mundane and true it wouldn’t work as tourist entertainment.

We know from very old fairy tales that there’s a long history of men fearing poisoning. If women are in charge of preparing the food, the food is one locus of control she might utilise to exact revenge. I note with interest that Blaikie has been widowed twice, which may or may not mean anything, but it might mean Blaikie chased older women for their inheritance, or worse.

If we read “Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You” at a metaphorical level, this haunted house story might be Alice Munro providing readers with a gender-inverted micro-narrative of murder to challenge readers. She may be pushing us to consider the idea that Nice, Beautiful women (in this case Char) or their invisible sisters (Et) are capable of murder, and sometimes they do murder men. Contemporary audiences are used to the idea that women can kill their husbands. 1970s audiences were less familiar with stories of violent women, and the ones they did know of were depicted as monsters, not the woman next door.

THE KING ARTHUR ALLUSION

The story shifts back to a few months earlier when Et told Char that Blaikie was freshly arrived back in town. The sisters invite Blaikie over for tea. They play ‘schoolteacher games’.

Et tells Arthur in a game of Twenty Questions that he should have picked King Arthur, his namesake. Arthur points out another supposed similarity: Both himself and King Arthur married beautiful women. But Et, prone to clear-eyed pessimism, is having none of that. “We all know how that turned out in the end,” she reminds him — a Munrovian nod to universal entropy. We might also read this as jealousy on Et’s part. I resist this reason, partly because it’s the most simple and stereotyped. (“Ugly women are naturally jealous of beautiful women.”)

Guinevere was the wife of King Arthur, the legendary ruler of Britain. She was a beautiful and noble queen, but her life took a tragic turn when she fell in love with Lancelot, one of Arthur’s bravest and most loyal knights.

Encyclopedia.com

Note that word ‘noble’ again. This small Ontario town was once noble, but is no longer — not in the literal sense of aristocratic nobility, but in the sense of ‘once commanded respect for no earned reason, which was therefore easily lost’. We can assume this town was once beautiful, as Char, like Guinevere, was once widely perceived as beautiful.

ET’S PARASOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

First, I need to define parasocial relationship, which goes beyond fandom. All relationships sit on a continuum between social and parasocial. Any given relationship is never at the 100% social end of the continuum, because no one can 100% know another person. So part of what we ‘know’ about another person happens inside our imaginations, even between sisters who are ostensibly as close as humans can ever get.

My take on Et: She is prone to parasociality, even in her most intimate relationships. I don’t think this is because she is lonely, or a woman, or has some kind of personality disorder. In fact, research tells us that parasociality correlates with extroversion. Big life changes also tends to push people towards parasocial relationships.

Of course, Et is a fictional character, so a better question than ‘Why does Et default to parasocial relationships?’ would be ‘What story function does Et’s parasociality fulfil?’

I would suggest that Alice Munro is reminding us that nothing and no one should be taken at face value. Whatever we encounter is at least some small percentage from our own imaginations. This theme is extended by the haunted house story-within-a-story and the unresolved mystery of the rat poison — unresolved precisely to remind us that we can never know the real truth of anything.

A very postmodern idea.

For more on parasocial relationships, see this post.