Perhaps the most unlikely pet is the European brown bear (the same species as the American grizzly bear), which the Ainu people of Japan regularly captured as young animals, tamed and reared to kill and eat in a ritual ceremony.

Thus, many wild animal species reached the first stage in the sequence of animal-human relations leading to domestication, but only a few emerged at the other end of that sequence as domestic animals.

Gun, Germs and Steel, Jared Diamond

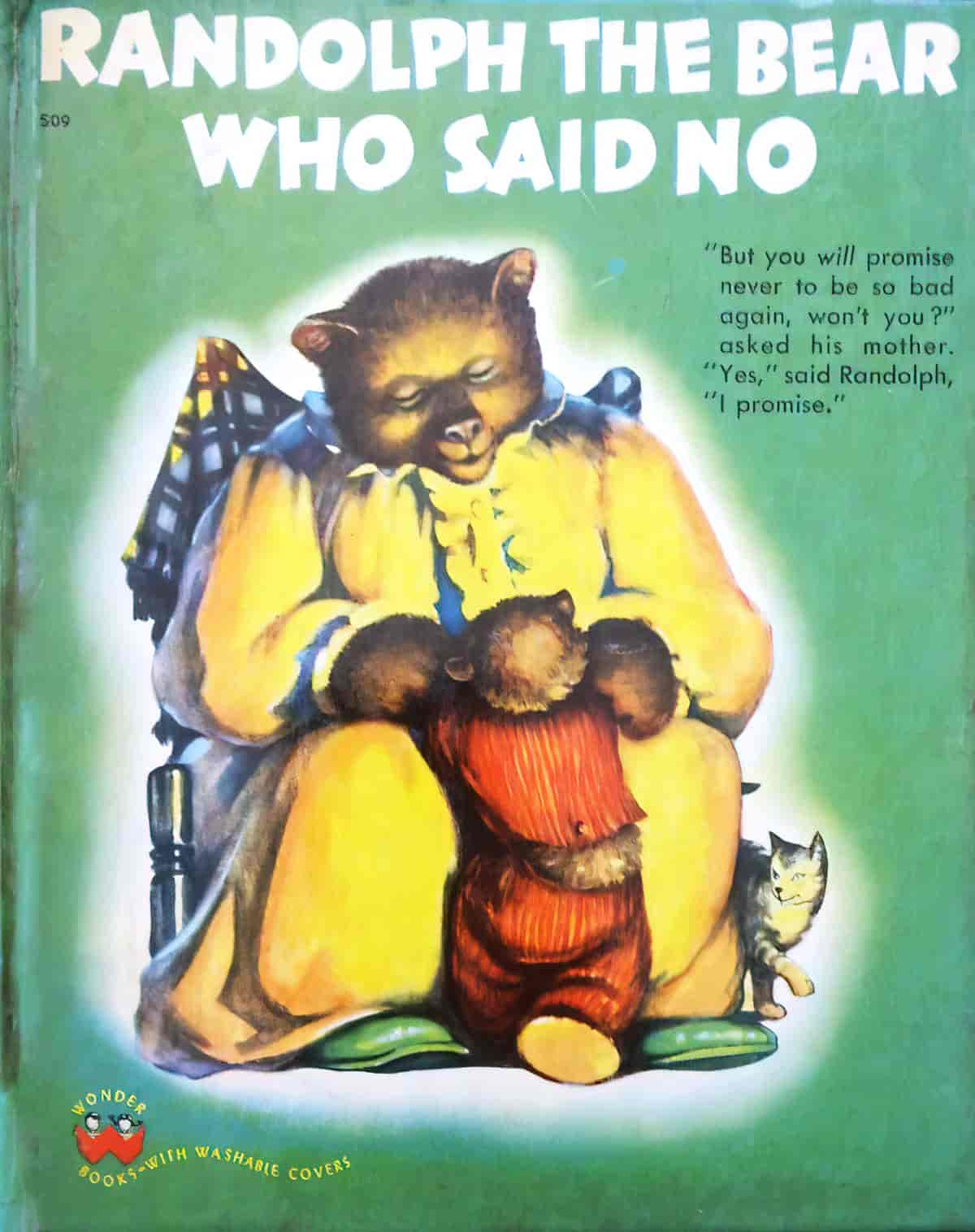

If you’re in need of some sparkle, here are (I think) two beautiful etymologies. To lick something into shape stems from a medieval belief that bear cubs are born without form, and need to be licked into bear shape by their mothers.

@susie-dent

THE GREAT BEAR BY LIBBY GLEESON

In this story, a bear is kept in a cage to perform tricks and basically be an exhibit. But one night the bear escapes, scares away the villagers and climbs up a pole into the sky, and flies away.

The message is obviously one about keeping animals in captivity (don’t), and I wonder if there are bigger themes in here as well, about reaching for the sky.

This one was shortlisted by The Children’s Book Council Of Australia but failed to engage my daughter. I think it was partly to do with the dark, sketchy drawings (by Armin Greder) which look to me a bit like an underdrawing.

I vividly remember owning a picturebook in a similar style as a child, and I didn’t like it solely because of its illustrations — illustrations that would intrigue me as an adult.

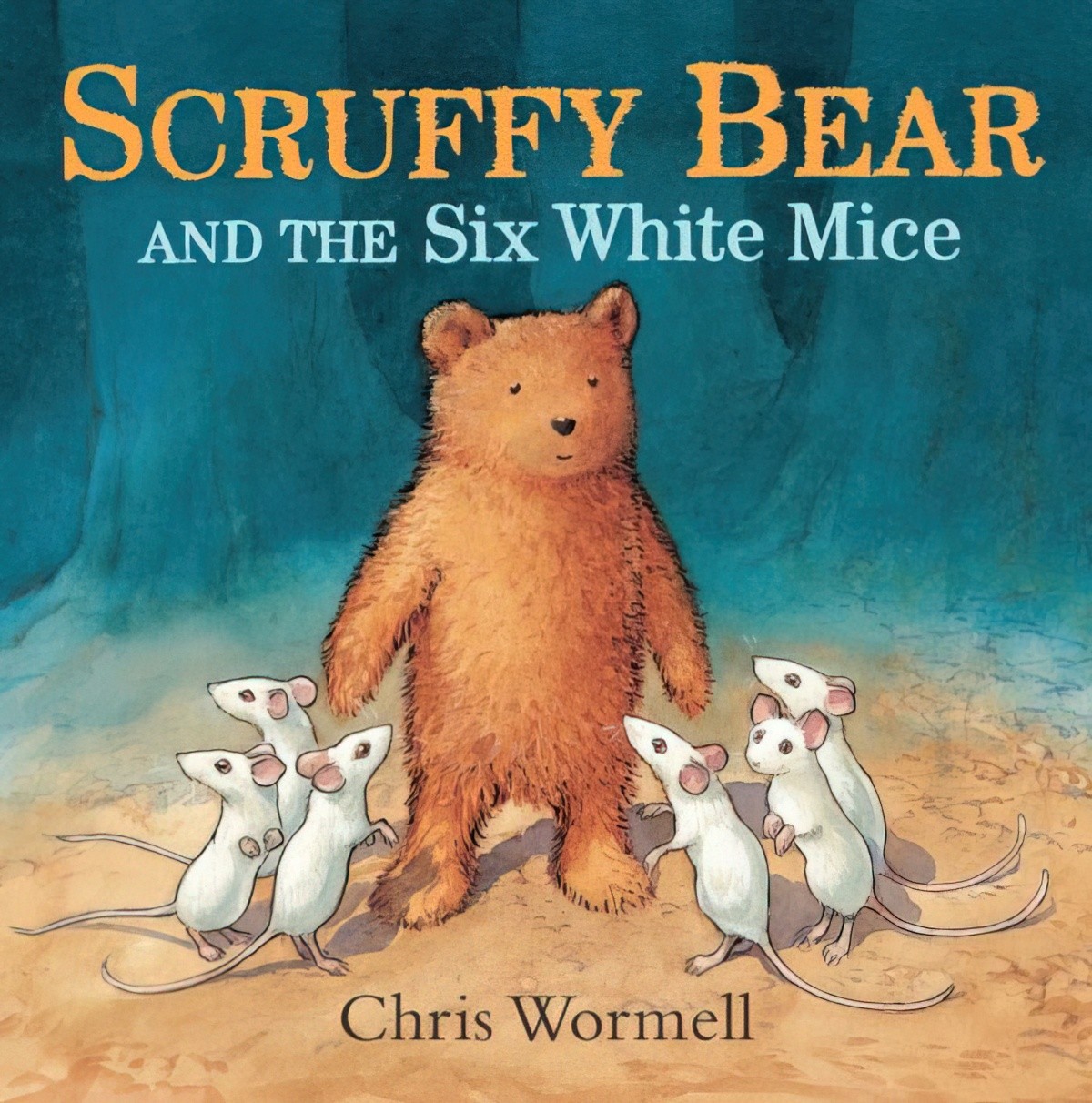

SCRUFFY BEAR AND THE SIX WHITE MICE BY CHRIS WORMELL

This is a pretty cute story, in which a bear protects six white mice by fooling three predatory animals (a snake, a fox and an owl) into thinking they’re something else (moon apples, furry eggs and snowballs respectively).

By the time the predatory animals have worked out that they’ve been fooled, the bear and his six white mice have gone. The page in which the fox, snake and owl realise they’ve been tricked is a deliciously scary moment for the child, who sees their, angry duped faces in close up.

What’s not clear (to my critical, adult mind) is why the bear doesn’t eat the mice. Do bears not eat mice? I would’ve thought so.

Still, bears get special exemption from the laws of nature, at least when it comes to picture books.

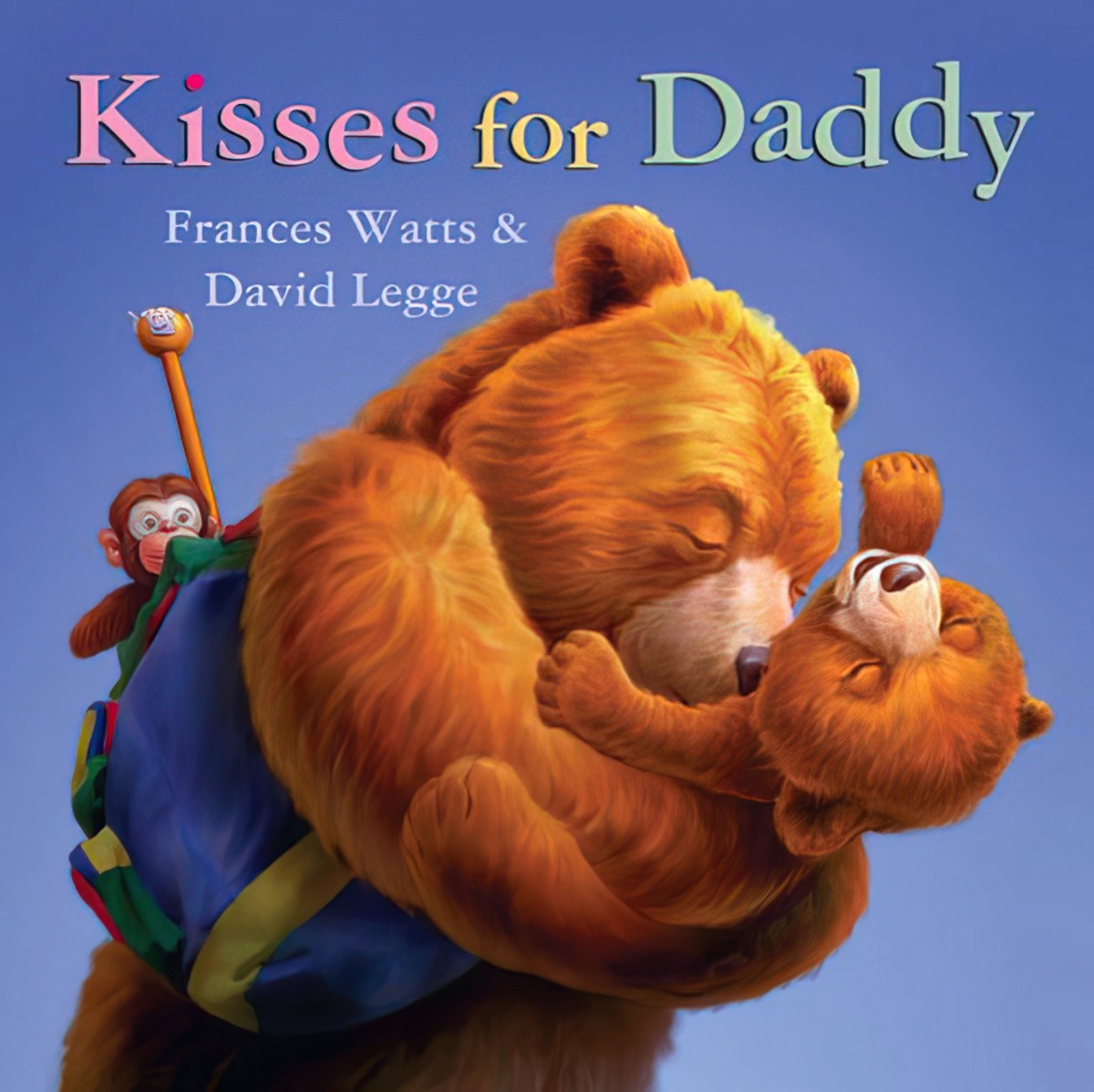

KISSES FOR DADDY BY FRANCES WATTS ILLUSTRATED BY DAVID LEGGE

There is a type of children’s story which I’ll call ‘Hugs and Kisses’. It’s usually bedtime, though not always, and we follow a happy, affectionate family as they hug and kiss each other and roll-around laughing happily until the child character is tucked safely into bed. All is well with the world.

In this story, the parents and child happen to be bears. An astute adult reader will see the end coming a mile off: the baby gets a ‘bear’ hug, of course.

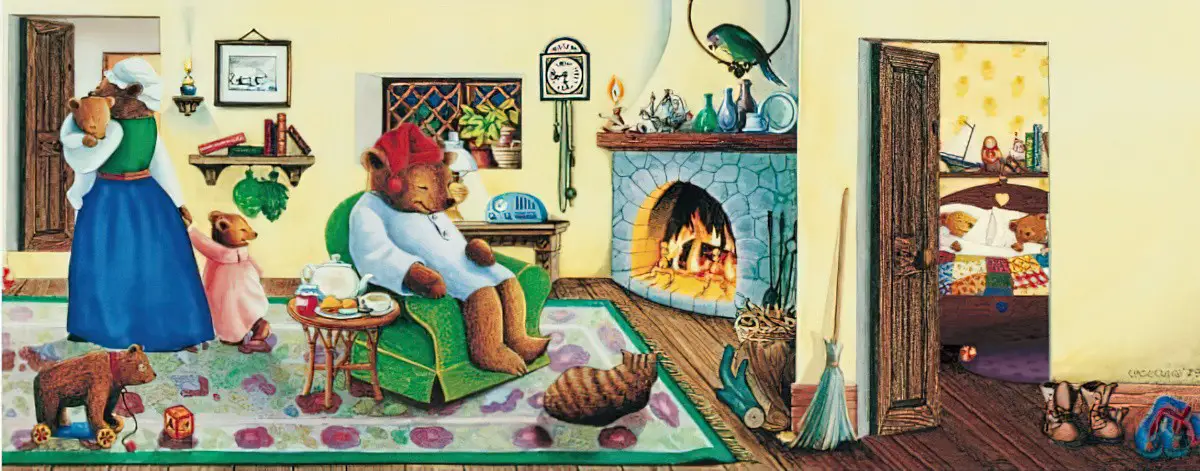

The illustrator looks like he really enjoyed rendering the bears’ fur. I’m not a fan of the creepy monkey who appears on most pages. (I have a thing about toy monkeys, along with tunes coming out of ice-cream vans and clowns.) This book is a good example of my main issue with some digital art: the elements of each picture don’t look sufficiently integrated together. While the bears look handdrawn, the lamp in the living room looks like an imported photograph. I do like illustrations to look like illustrations, even if heavy use has been made of photo references. Others will have no such problem, and indeed many may prefer this style, which only digital art can offer.

ADDIS BERNER BEAR FORGETS WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED BY JOEL STEWART

It seems I often read a picture book in which the story is lacking, or ill-composed, but it is accompanied by fantastic artwork. That happens more than the other way around. But this book is an example of a story which I really like accompanied by less masterful (but still adequate) illustrations, rendered in pastel watercolours, held together (too) loosely by incomplete black pencil lines. I wonder if this author/illustrator would consider himself a writer first, an illustrator second.

The story depicts perfectly how I felt about London when I went there for a while; I’d been attracted to it, but as soon as I got there I wondered why I’d come. It took another while to find my purpose for being there. This is a message that perhaps adult readers are more likely to appreciate than younger ones. The resident four-year-old wasn’t captivated by this story and asked to read a different one, but I was keen to see it through, and enjoyed the atmosphere of it. I also liked that the story was told partially through the pictures, leaving the reader with sparse words. Surely that is the point of picture books, otherwise they might as well not be picture books. I’m noticing that this sort of cohesion is more likely with works in which the author/illustrator is the same person.

One thing though, I thought the last page could have been more original. I think the last page of a story is very important, whether it contains words or just an image. This one ends with, ‘It was a day that Addis Berner Bear would never forget.’ There’s nothing particularly wrong with that, but it doesn’t resonate, either.

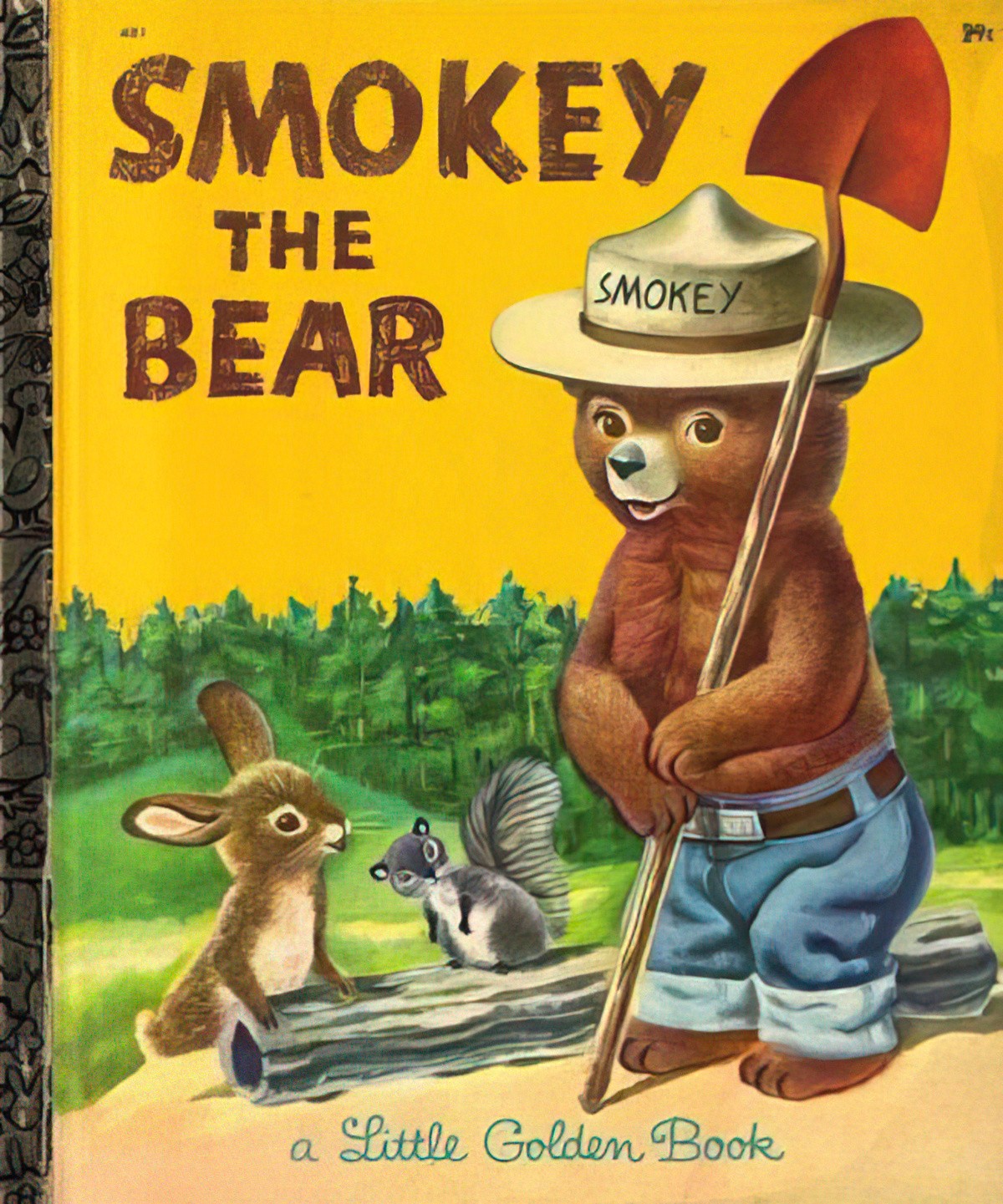

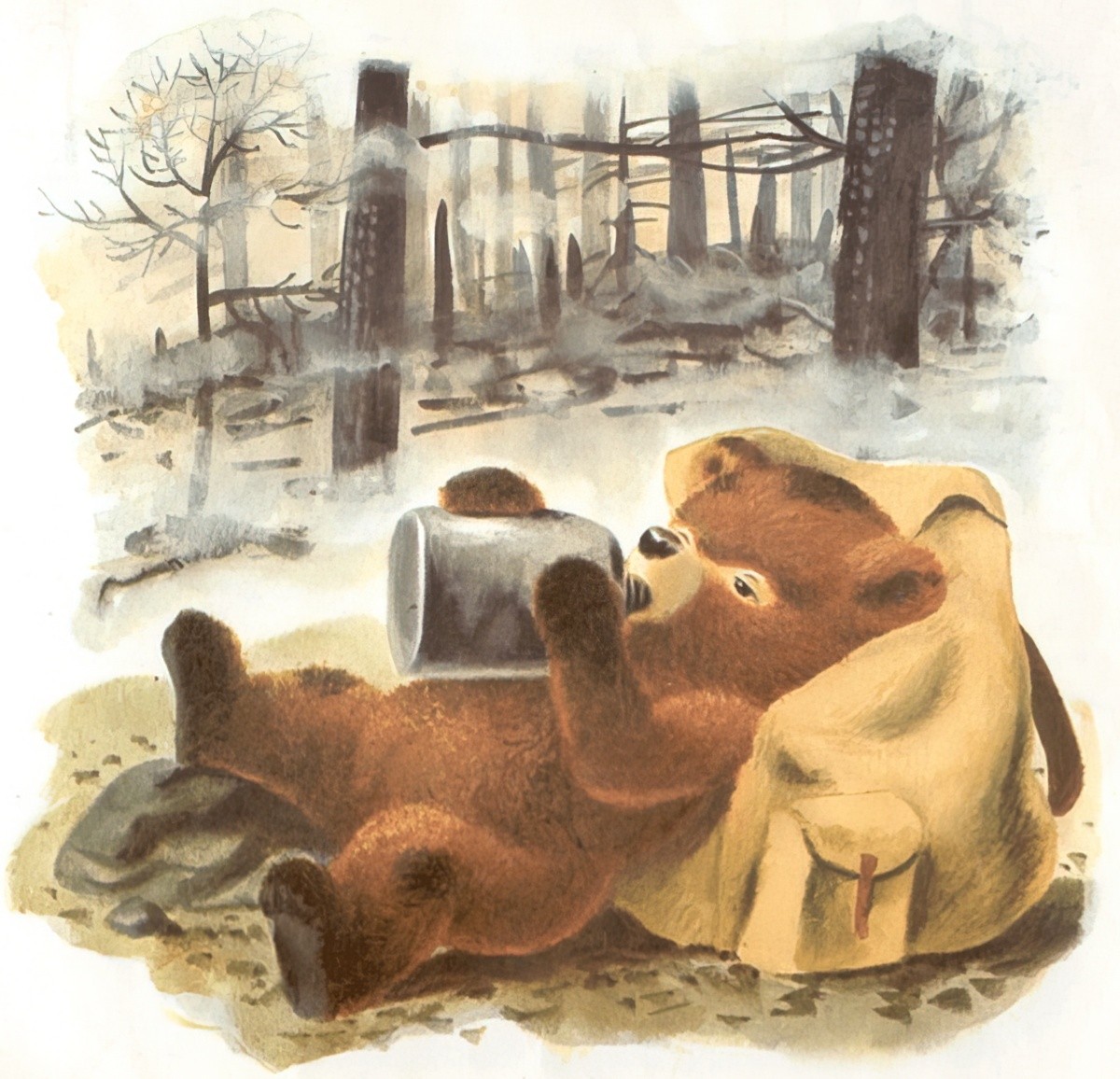

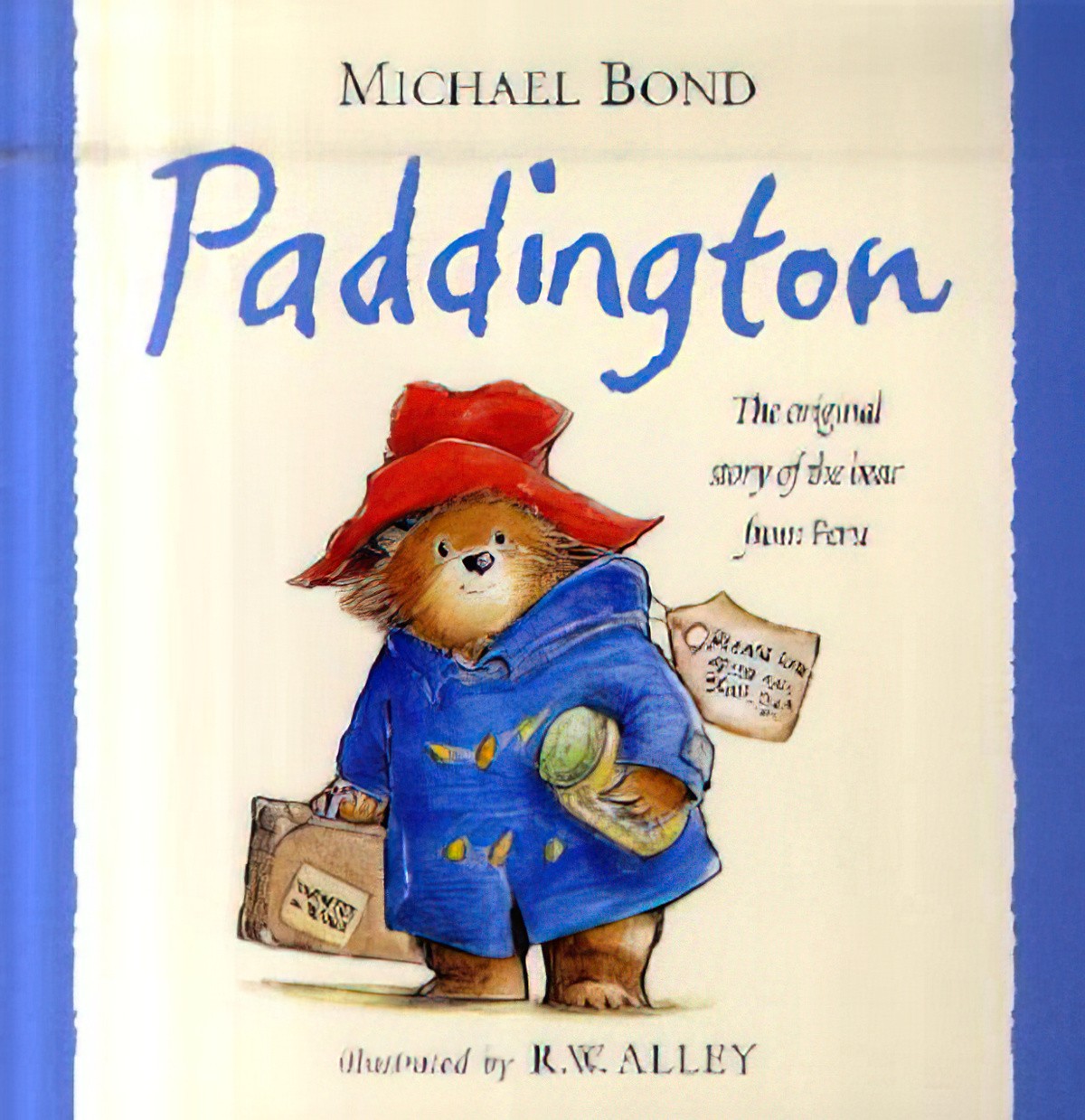

PADDINGTON BY MICHAEL BOND ILLUSTRATED BY R.W. ALLEY

Paddington Bear is a phenomenon, but unlike some other phenomena which don’t deserve their highly-marketed popularity, this character is lovable in his own right. I didn’t know this until I opened this very picturebook though, because I’d never read any of the books. It’s high time I did, since this bear is over 50 years old.

The picturebook gives a keen sense of London — a London in a former time, full of white-skinned characters, and a Paddington Station that’s not nearly so crowded as it is today. Although I enjoyed a lot of my time in London a few years ago, books like these make me wish I could have visited London in the 1960s.

I think I’m going to adopt and use the phrase, ‘This isn’t a bit like Darkest Peru’. Which is funny, because when I think of Peru, I don’t think ‘dark’.

Radio New Zealand did an interview with Michael Bond, a laid-back, kindly personality (as you might expect) on Paddington Bear’s 50th birthday.

Speaking of New Zealand, there was a Kiwi band who called themselves The Paddington Bears. That was 1969. I don’t know what happened to them. If Wikipedia had existed back then they may have got a two line entry. Alas.

More on Paddington Bear from Mental Floss

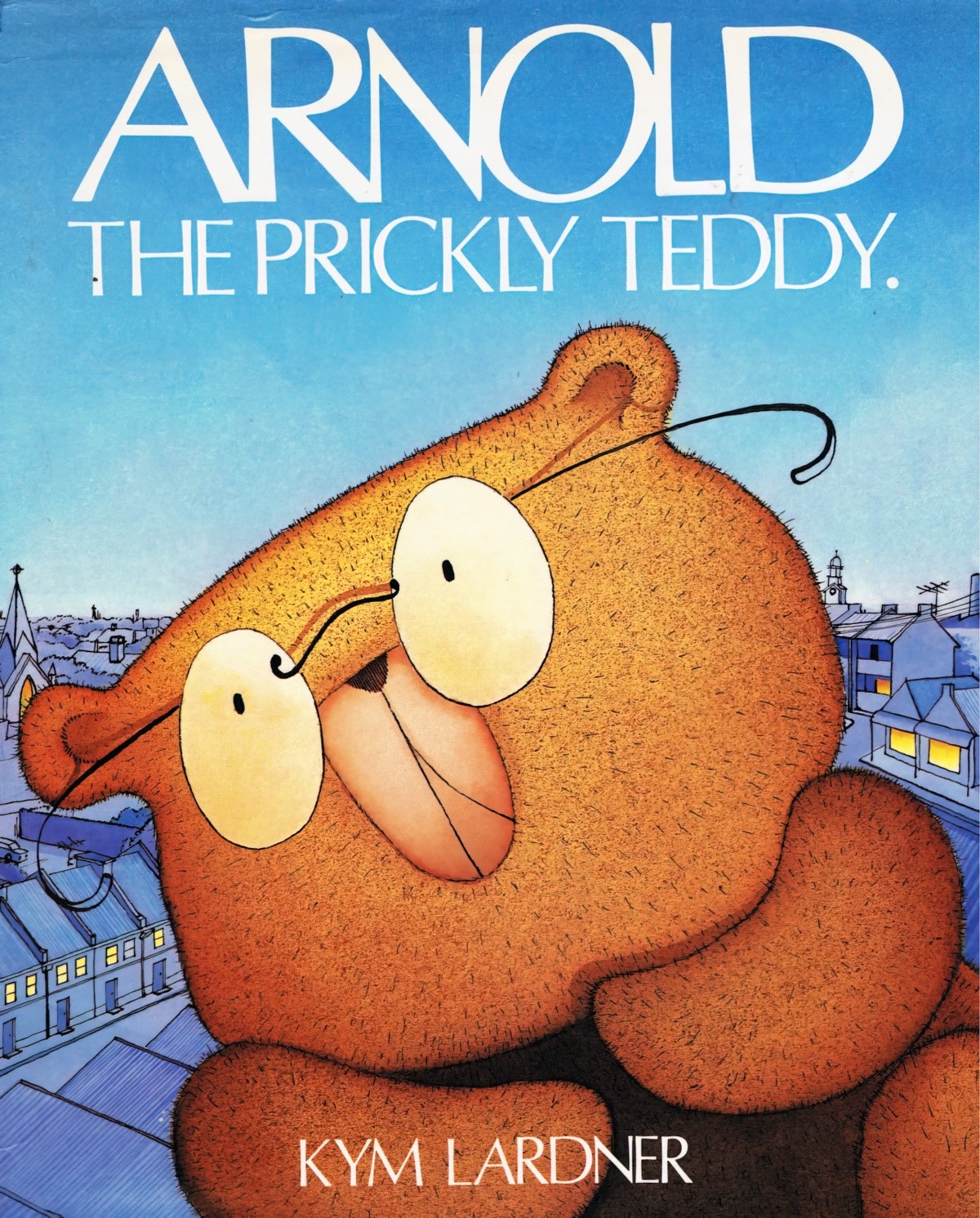

ARNOLD THE PRICKLY TEDDY BY KYM LARDNER

A teddy bear is too prickly to be appealing in a shop, and so the shopkeeper throws it into the skip where it is rescued by a passing boy. In a few deft strokes we see that the boy is from an economically impoverished background and for lack of alternatives the prickly teddy becomes favourite. Over time, the teddy bear loses its prickliness and becomes soft, metaphorically mirroring the transformation that often takes place when we get to know someone really well.

The ending of this story feels a little abrupt, but after a few seconds I realised that the ending was perfect.

Also comes in a 4 story collection.

LOVE IS A HANDFUL OF HONEY BY GILES ANDRRAE ILLUSTRATED BY VANESSA CABBAN (1999)

I’m far too old and pessmistic for overtly cutesey books like this one.

The story follows a bear in a sort of manic state as he makes his way through a day full of delights. (The animal characters could equally be female — interesting that I assume maleness when no gender is specified. Maybe it’s the absence of pink?)

The story starts off okay with, ‘Love is that warm cosy feeling/You get when you’re cuddling your mum’, but as the day progresses, the descriptions are less about ‘love’ and more about other feelings dressed up as love: And then when your tummies are grumbly/Love is unwrapping your treats (consumerism)/ And love’s stuffing everything all in at once/Leaving masses of mess on your cheeks (greed).

Perhaps my skepticism is only a reflection of the fact that in English we don’t have very specific words to describe the different types of ‘love’. At any rate, I had a hard time reading this one out loud without emitting a groan.

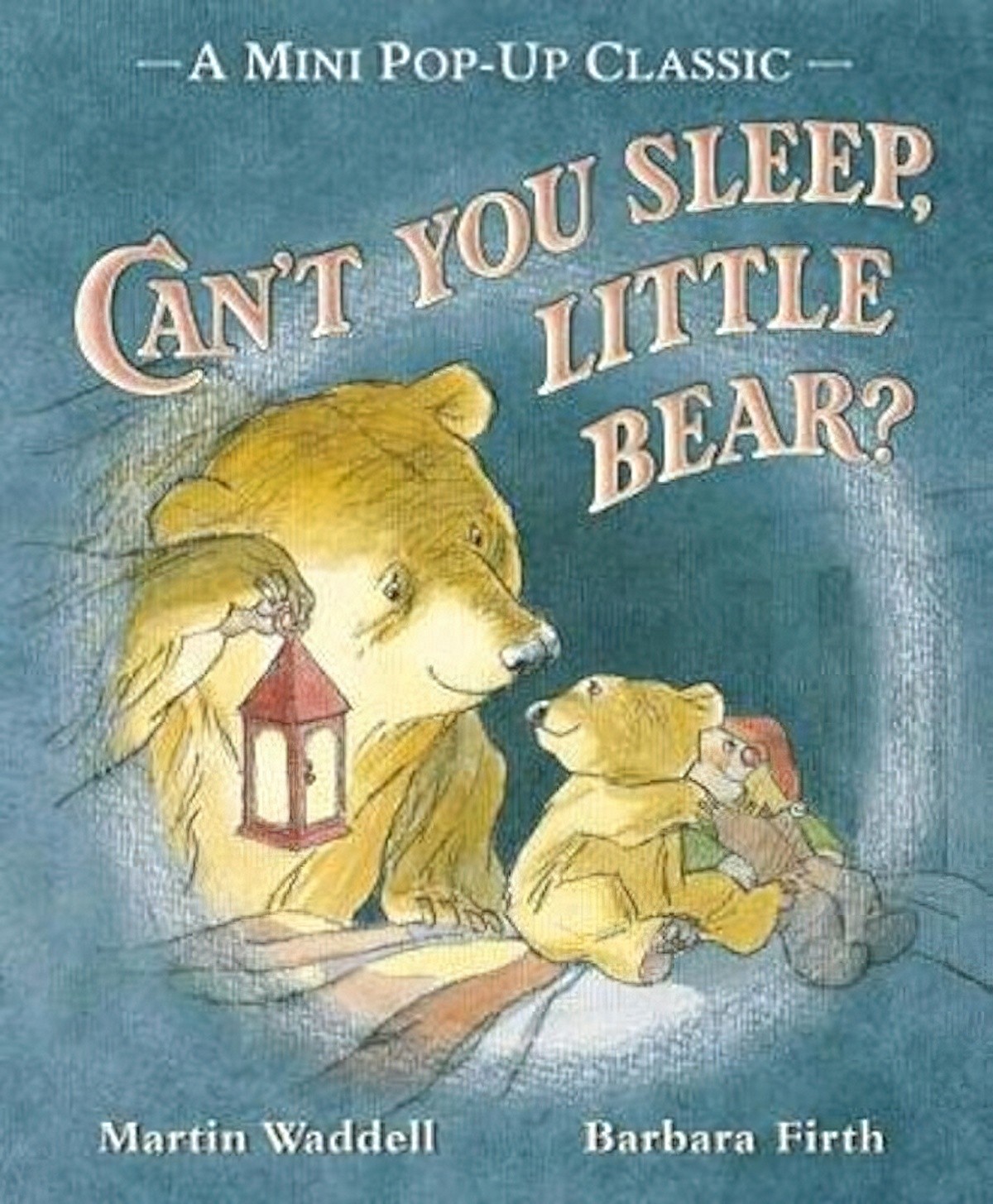

CAN’T YOU SLEEP, LITTLE BEAR? BY MARTIN WADDELL, ILLUSTRATED BY BARBARA FIRTH

Honestly, this would have to be the most irritating going-to-bed book I’ve read yet, which no doubt speaks to my own views on sleep for the little ones. As far as I’m concerned, you put the kid to bed, and then you leave them the hell alone.

That’s not what happens in this story. Instead, there’s a big bear and a little bear in a furnished cave. The big bear is trying to read, but the little bear can’t sleep. So the stupid big bear decides to turn on a light for the little bear. Little Bear has a doctorate in manipulation, and asks for bigger and bigger lights, until the cave is so well-lit that even a chronic narcoleptic wouldn’t get any shut-eye.

I thought this was just my own adult take on proceedings, until the four-year-old laughed and said, ‘Of course Little Bear can’t get to sleep with all those lights on!’

That Big Bear needs a slap. Because Little Bear is going to be mighty grumpy tomorrow. Good luck to Big Bear with THAT.

(By the way, this is one of Professor David Beagley’s favourite books, which just goes to show.)

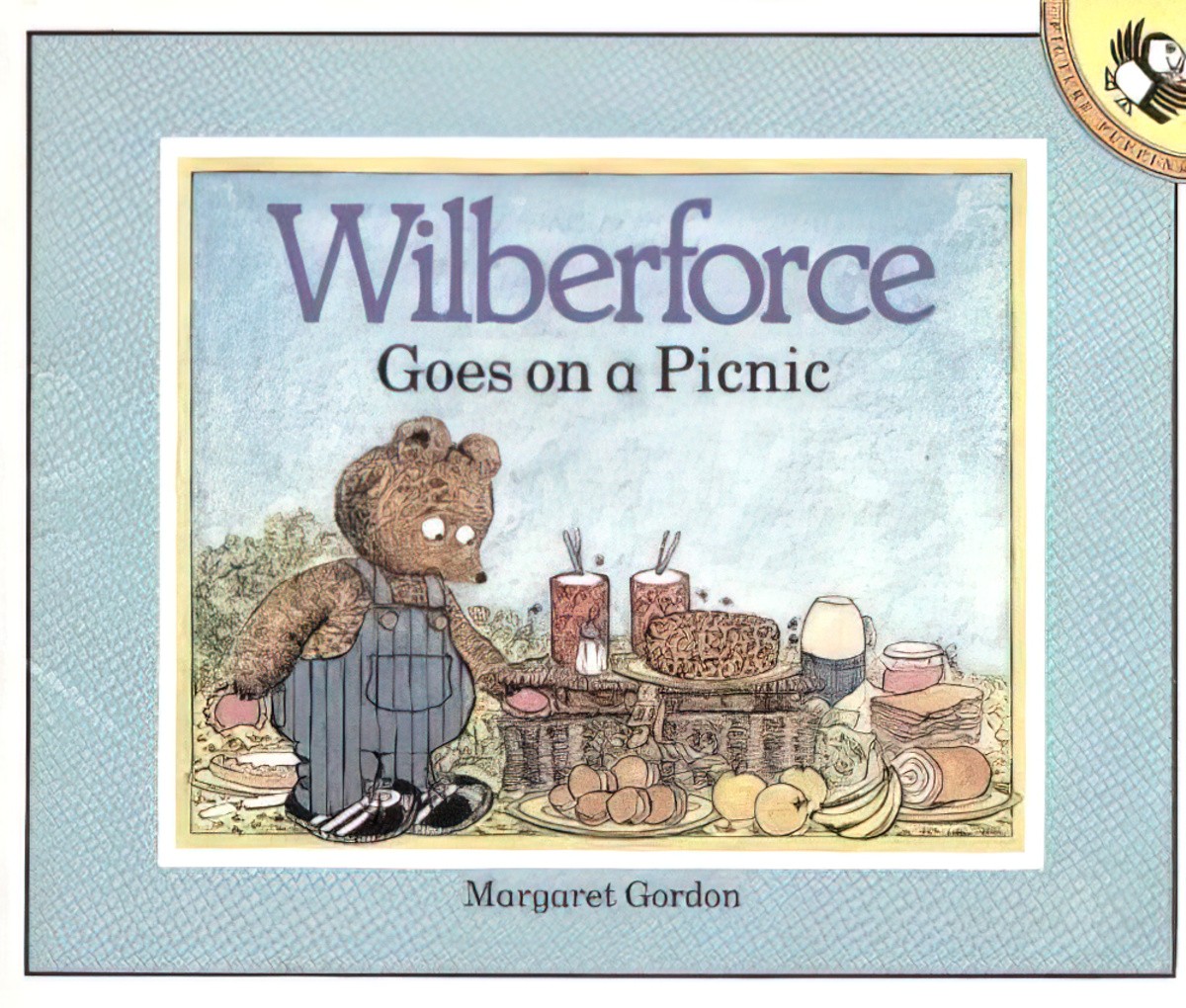

WILBERFORCE GOES ON A PICNIC BY MARGARET GORDON (1982)

This is another story about a family of bears, which could just as easily be a family of people.

The words in this story are very simple: sequential and uneventful, of the kind that might almost have been written by a child when asked to recount what he did at the weekend:

Waving goodbye to Mother and Baby, off they went through town… and then through the country… until they found an ideal picnic spot.

The simplicity is effective because this is no doubt how the little bear remembered his picnic with his grandparents, looking back fondly after time. But the pictures tell us a very different story, in which everything that can go wrong on a picnic does go wrong: Wilberforce mucks around in the bathroom, smearing toothpaste onto the mirror, while the text below alerts us to the fact he’s supposed to be brushing his teeth and combing his ears. He gets into the picnic basket before grandmother has finished preparing it. The car has mechanical issues and grandfather needs to start it. (This story is old enough to have very traditional gender roles.) Sure enough, all sorts of bad things continue to happen, until it rains (as it often does when characters go on picnics in story books) and the story ends as unpretentiously as it begins:

“After supper we went to bed. Grandmother and grandfather finished supper, and then they went to bed too.”

Such a simple story works because of the counterpoint in the illustrations. The reader has just had two stories, not two, and an adult reader is likely to empathise with the adult bears, who probably aren’t having the greatest time as Wilberforce almost drowns himself and gets into other mischief.

Before reading this book I’d just been listening to a podcast about the American dietary guidelines, which came out in 1982 and haven’t changed much since, ‘food plate’ or ‘pyramid’. In 1977 a scientist called Ancel Keyes published some (flawed) research which led to the American government recommending that we all cut down on dietary fat and increase our servings of whole grains. This came into effect in 1980, just two years before this book was published, and so I made note of the fact that this family of bears is eating the pre-1980s breakfast of bacon and eggs and sausages. In picturebooks published subsequent to this one we’re likely to see a box of extruded cereal on the kitchen table to indicate breakfast time, which makes me want to delve further into a study of food in picturebooks.

As an unrelated side note, this family has gone back to the pre-obesity-epidemic days and we eat meat and eggs for breakfast. Our health is far better for it.

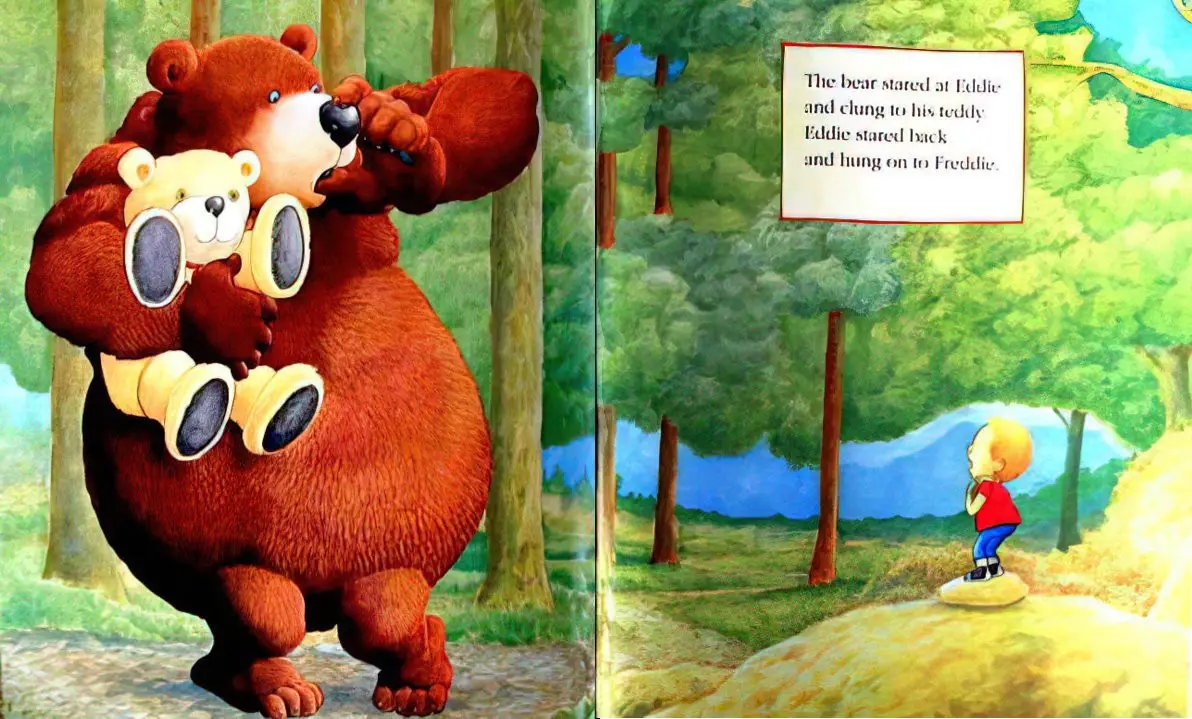

MY FRIEND BEAR BY JEZ ALBOROUGH

This is a sequel of sorts to It’s A Bear! which my daughter absolutely loves. This time Eddy is in the woods all alone when he comes across the very large bear who happens to be benevolent. This story would appeal big time to preschoolers who spend a lot of time talking the parts of teddies.

THE VERY CRANKY BEAR BY NICK BLAND

I know young children who love this book. I do not love this book.

The Problem With Raising Good Girls points out the problem with Australian author Nick Bland’s The Very Cranky Bear, which was chosen for national simultaneous storytime 2012, and was consequently read and studied by my preschool daughter. I agree with the issue raised in that article, and feel that deeper thought should go into which books are chosen as basically ‘required reading’ for Australian kids.

Stories about self-sacrificing girl characters can be seen the world over. One South Korean example is How I Caught A Cold (설빔(남자아이멋진옷/ 여자아이고운옷) by Dong Soo Kim.

What does a flock of featherless ducks have to do with a little girl catching a cold? It all begins with a new down winter jacket. One day, she discovers a feather emerging from it. That night, she goes to sleep wondering about the feather and begins dreaming of featherless ducks who feel cold. The girl distributes the feathers from her jacket. Finally, all the ducks feel warm but the girl doesn’t.

The World Through Picture Books

THE BERENSTAIN BEARS

Though dated in their worldview, these books are popular with the resident six-year-old.

BABY BEAR BY KADIR NELSON

Kadir Nelson delivered a presentation about art and life, which is summarised at Philip Nel’s blog.

THE BEAR’S LUNCH BY PAMELA ALLEN (1999)

Wendy and Oliver decide to have a picnic in the woods, but they get more than they bargained for when they are approached by a ferocious black and growling bear.

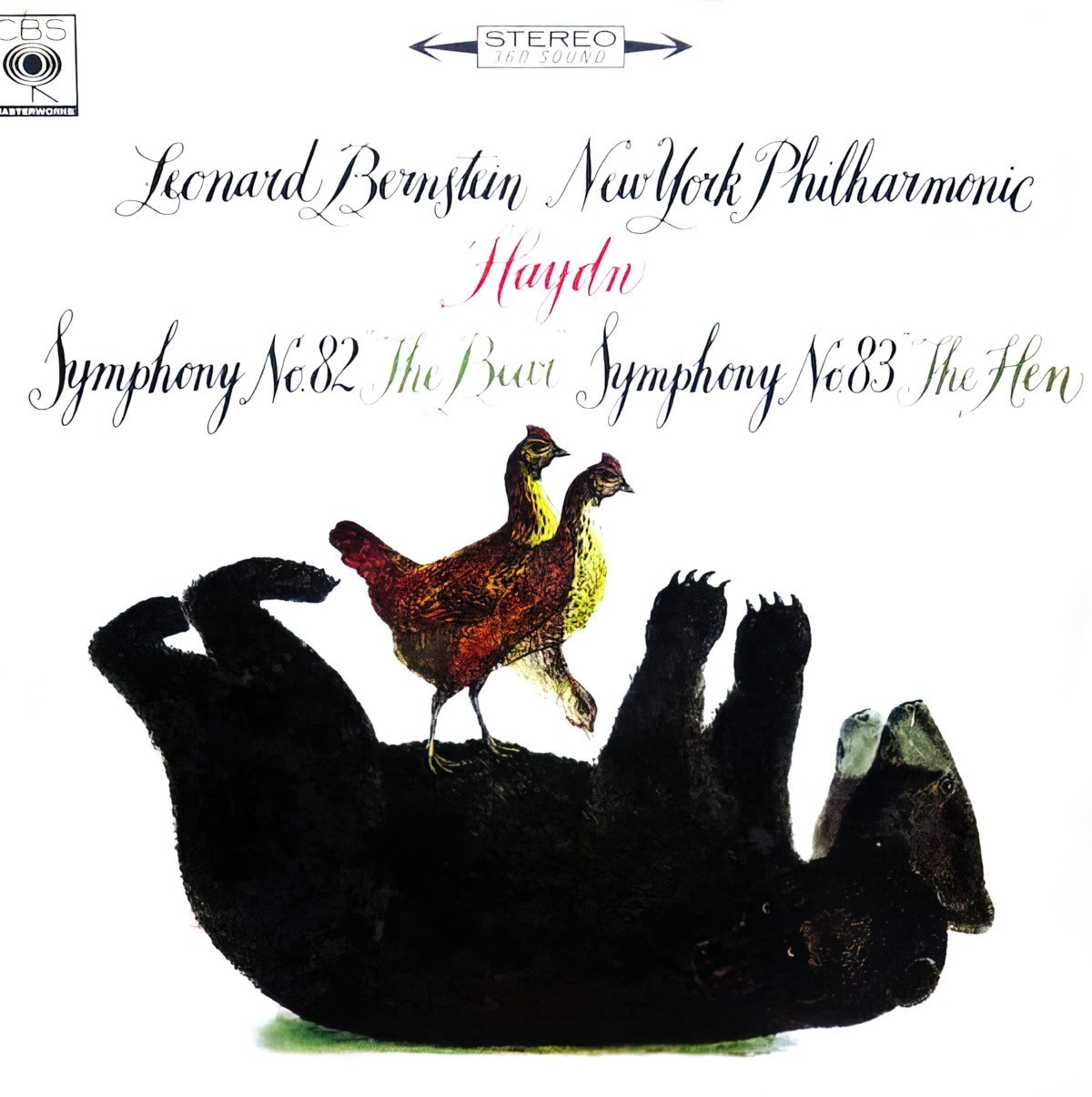

Why the world can’t get enough of bears in film and literature

Goldilocks and the Three Bears

Bears In The Night by Jan and Stan Berenstain

It’s The Bear! by Jez Alborough

Northern Lights by Philip Pullman

[W]e should note that — bare naked, in its five-pointed-star shape — the stuffed bear fuzzily resembles our own bodies. And unlike other creatures, and as dancing bears at circuses reveal, these animals are also like us in being fuzzily upright. And for the young who seek the satisfaction of snuggling, the fur-covered teddy is — well, fuzzy. There is, in other words, a simple explanation for the overpopulation of bears in Kidsworld: the bear presents a “fuzzy” version of ourselves.

That “fuzziness” permits the child to think the “same only different,” to understand something under the guise of marginal difference.

Jerry Griswold

![Northwest Romances v16 n05 [1948-Su] bear](https://www.slaphappylarry.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Northwest-Romances-v16-n05-1948-Su-bear.jpg)

THE SLEEPYTIME BEAR

It must be said, the founder of Sleepytime Tea was a eugenicist who based their “inspirational” tea bag quotes off a racist space bible.

RELATED

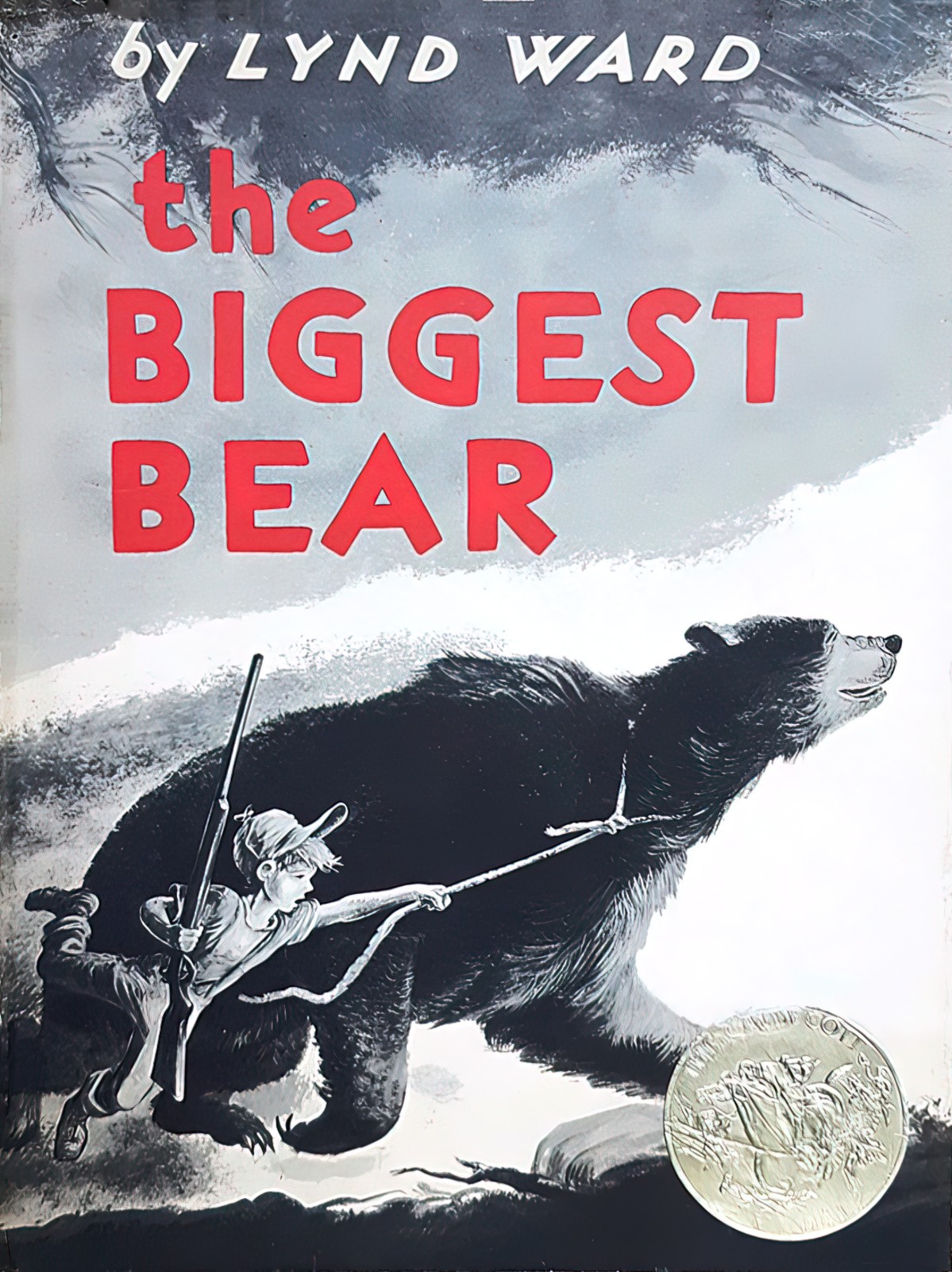

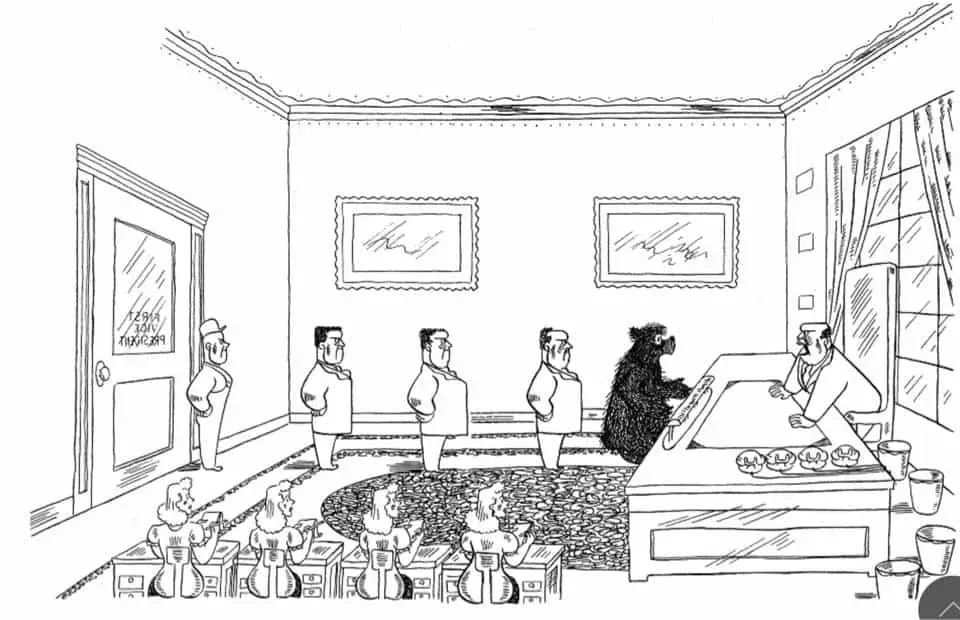

Frank Tashlin’s The Bear That Wasn’t.

Header illustration: By Peter Kľúčik for unpublished edition of The Hobbit