Winnie the Pooh is basically a modern version of an archetypal legend: The story of a peaceful animal kingdom ruled by a single benevolent human being. Like Adam, Christopher Robin gives names to his objects.

The Pooh stories came at the very end of the First Golden Age Of Children’s Literature, as described by Peter Hunt:

THE AUDIENCE

- Winnie the Pooh has been described as not really a book for children, but rather ‘collegiate’. Sure enough, my mother bought me the complete hardcover works when I was in university. I hadn’t truly read them until then — like Seuss’s The Lorax, the stories had always been enjoyed more by my mother than by me. In the early years the books were very much in vogue among adults but were later condemned by some as being smug/bourgeois/whimsical. Winnie is like The Bee Gees — he tends to go in and out of fashion, but unlike The Bee Gees, he’s currently in fashion. People don’t complain about his whimsy much these days.

- Roger Sale said that the Pooh books are essentially about the fact that Christopher Robin is now too old to play with toy bears.

- Maria Nikolajeva says that ‘the books present a subtle balance between the creation of Arcadia and the subversion of it, so that our final interpretation of them can easily topple over to either side, which we also see clearly in many studies of Pooh’. She explains that Milne tries to create an illusion that Paradise is indeed eternal, while the text subverts the author’s intention.

- Apart from his Pooh stories (written 1924-1928) A.A. Milne wrote plays for adults. After his four Pooh stories that’s all he wrote, until he died in 1956, dissatisfied that he had ‘only’ found fame as a children’s writer.

FOOD IN THE POOH STORIES

Food is an important part of Pooh’s paradise, though surprisingly little is said about it compared to, say, The Wind In The Willows. Pooh is fixated, of course, upon ‘hunny’.

As a side note, human evolution explains why we love honey:

The honeyguide lives in much of Africa, where it eats the wax, brood, and eggs of honeybees. In this, it is relatively unique. Wax is indigestible to most animals. The honeyguide has been simultaneously blessed with the ability to eat wax and cursed with the dilemma of how to obtain it. Honeyguide beaks are too small to break into beehives. Humans have a different problem. We crave beehives for their honey. We are willing to do almost anything to get to honey. In Thailand, little boys are sent a hundred feet up into trees with a smoking stick to do big struggle with three-inch-long giant bees and take from them their honey… Honey, to paraphrase the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss has “a richness and subtlety difficult to describe to those who have never tasted [it], and indeed can seem almost unbearably exquisite in flavour… [It] breaks down the boundaries of sensibility, and blurs its registers, so much so that the eater of honey wonders whether he is savouring a delicacy or burning with the fire of love.”

The Wild Life Of Our Bodies, by Rob Dunn

- Pooh is often punished for being greedy, though the punishment is rather mild compared to the punishment in most gluttony stories. (Compare with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.)

- Food is always joyful. Most adventures end with Pooh going home to eat lunch. He is always excusing himself to go home to eat. He lives to eat. Pooh immediately interprets unfamiliar words as food, which is a good source of humour. A similar technique is used in the more modern book Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, in which the animal main characters structure their days around mealtimes, and almost don’t live to tell the tale. Contemporary children’s writers structure stories similarly. Kate DiCamillo’s Mercy Watson books always end with food. Pettson and Findus stories also end with the sharing of food. All of these stories are set in a safe environment where food is always there, always a comfort.

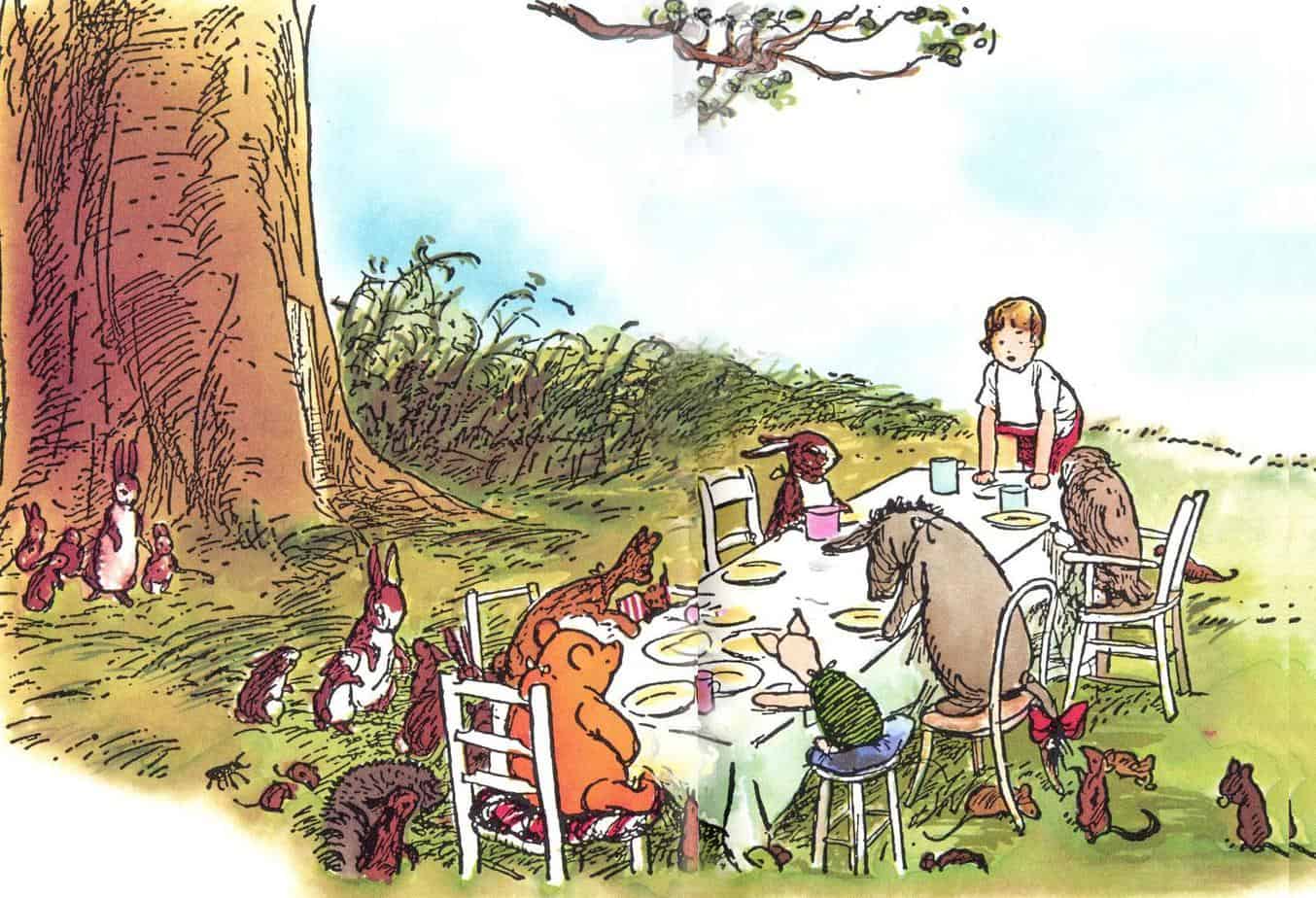

- As in many children’s stories, a picnic in the Pooh stories is an important part of many an outing.

- Food takes a less significant role in the stories once they move from mythic to linear (i.e. when changes start to occur), when Christopher Robin’s departure from this world is imminent and later becomes a fact. Food moves into the background because emotional development comes to the fore.

THE PLOTS OF WINNIE THE POOH

- Drama and excitement centre on the capture of strange animals or the rescue of friends in danger.

- The danger is always from natural causes: accidents, floods, storms, though Minotaur opponents can be imagined (e.g. The Woozle).

- As soon as real fact or observation is introduced, the elaborate system the characters have concocted to explain how the world works collapses. The story about the Woozle illustrates this. (The Woozle Effect is a phenomenon whereby an incorrect fact is cited so many times that it becomes largely accepted.)

THE SETTING OF WINNIE THE POOH

- Alison Lurie sees Pooh books as an intact idylls, with their strong “reversal of parental authority”. The Forest is a self-contained universe without economic competition or professional ambition. This is similar to the idyll in the Moomin stories. Apart from occasional bad weather, there’s nothing unsafe about this world.

- Although the place has no GPS coordinates, the setting suggests Milne was influenced by pre-1900 Essex and Kent, where Milne spent his holidays as a child. (At least, it’s more like this than like the more thickly settled countryside of Sussex, where he lived as an adult.) The landscape of the Pooh stories is quite bare and uncultivated, comprising mostly heath, woods and marsh. There are many pine trees, but the most common plants are gorse and thistles.

- Rain, wind, fog and snow are all common — this is a world with all four seasons.

- The world is a stable one. Tigger and Roo’s arrival in the Forest is like the appearance of a sibling in early childhood, inexplicable and unexpected. Both characters soon become an integrated part of the idyllic world.

- Humphrey Carpenter sees in the Pooh books the First Golden Age’s farewell to enchanted places.

- Some critics say that Milne wrote these books because he himself was estranged from his parents, and the world he created is a kind of escape. But other authors wrote similar worlds, and they were not estranged from their parents. (Astrid Lindgren, Tove Jansson etc.) I think we should be careful about psychoanalysing authors who create fantasy worlds and stick to the texts, sometimes in relation to other texts.

- The toys represent the childish part of Christopher Robin. They cannot follow him out into the Wide World.

- All scenes that take place at Christopher Robin’s house take place outdoors, including the party he gives at the end of the first book.

- The small, self-contained world of Winnie The Pooh is a bit like the world A.A. Milne grew up in. His father was headmaster of a small suburban London school for boys — Hensley House. Milne’s sons joined classes as soon as they were old enough. In this environment there is no economic competition or professional ambition. There are also no cars, planes, radios, telephones or war.

- Homes and houses play a significant role in the books in general, though. But home doesn’t exactly represent security — Owl’s house gets blown down. (This anticipates Christopher Robin’s departure.)

- The Forest is a natural world, where civilisation has not yet entered, at least not in the beginning. It’s basically a modern version of an archetypal legend. A peaceful animal kingdom is ruled by a single benevolent human being. But the final threat to the Forest comes from knowledge and education. Pooh’s poems represent oral, mythical culture but the education Christopher Robin receives on the outside is written and therefore linear. When Christopher Robin writes his first correct sentence, he takes a step away from the world of innocence.

- The Forest equals a child’s inner landscape. Forests equal the subconcious, across all forms of storytelling. Look to fairytales for the clearest examples of that.

THE CHARACTERS OF WINNIE THE POOH

- The characters are humanised toys rather than humanised animals but there’s not much point in making a distinction. Each of their characteristics doesn’t have much to do with their real-world animal counterparts, except that Piglet likes Haycorns (as do real world pigs, apparently).

- Milne claims that he did not invent most of the characters but merely took over the toys that Christopher Robin happened to have. He looked at their faces and “merely described” what anyone could see for themselves about their characters. “Only Rabbit and Owl were my own unaided work.” However, for those inclined to take a closer look at Milne’s life, it is thought he subconsciously based the characters’ relationships on his own. Alan was his father’s favourite son. Likewise, Winnie-the-Pooh is the favourite of Christopher Robin. Milne senior is Owl — as a child A.A. Milne thought his father knew everything but later realised a lot of what he’d ‘known’ was wrong. (An experience that happens to any adult, perhaps?) His mother is thought to be Rabbit, living in a state of preoccupation with small responsibilities and bossy concern for the duties of others. (Notice that his parents are the only characters Milne invented for himself.) Milne was closest to his brother Ken, only sixteen months older than he was. Like Pooh and Piglet, these two were inseparable.

- Apart from Kanga and Roo there are no family relationships — another similarity to a boys’ school.

- Like a schoolboy, Pooh lives in a world of eccentric but loyal friends.

- Their main activities: eating, exploring, visiting and sports.

- Some feminist critics have ascribed Pooh with gender characteristics. Children’s literature critic Maria Nikolajeva argues for a gender-free Pooh. The Forest is a ‘pregender’ universe. Note that the voice of Pooh, when adapted for television/film is quite high pitched, though narrated by an older male. This is both ‘youthful’ and results in a gender-ambiguous character. I argue that no character can be genderless because in English we have no gender neutral pronoun. (This may be starting to change, with an increasing number of people identifying as non-binary or agender.) The characters are ‘sexless’ but this does not mean they’ll be read as genderless. The archetype of the wise owl, for instance, is always, always coded male. It doesn’t really work otherwise, because the realworld counterpart upon which Owl is based is the patriarchal male of academia — a role unavailable to anyone other than the highly educated white man. (These characters probably can’t be race free, either.)

NARRATIVE PERSPECTIVE IN WINNIE THE POOH

- The story progresses toward an increasingly adult, detached view of the events.

- The metadiegetic, didactic narrator gradually disappears. Some critics really don’t like this adult-like narrator’s voice, thinking it is intrusive. (Metadiegetic pertains to a secondary narrative embedded within the primary narrative. The secondary narrative can be a story told by a character within the main story or it can take the form of a dream, nightmare, hallucination, imaginary or other fantasy element.)

- This kind of narration is typical of idyllic fiction.

- In the Pooh stories, there is a metafictive father telling these stories to a metafictive son over and over again.

- There is much irony between the words and the pictures, for example when Pooh is stuck in the hole because he’s eaten too much honey. Christopher Robin reads him a ‘sustaining’ book, which happens to be an ABC book, and opens to the page for ‘Jam’. Both Milne and Shepard (the original illustrator) make fun of the child. This has been called the Mark Twain Wink.

- There is another sort of irony addressed to adult co-readers. These passages mostly appear at the beginning of Winnie-the-Pooh — there are none in the sequel. They take the form of condescending conversations between the author and Christopher Robin. The following example shows that behind the godlike character of Christopher Robin (who fictionally created the cast in his mind), is the even more godlike figure of A.A. Milne, who created everything. (Similarly, E.B. White engages in double address via Fern’s father, who acts as the voice of the author.)

THE COLLECTIVE UNCONSCIENCE (PROTAGONIST)

- Pooh has psychological shortcomings that make his character interesting. His virtues and faults are common to the Every Child: simple, natural, affectionate. He continually falls into ludicrous errors of judgement and comprehension. He is so greedy that he eats Eeyore’s birthday jar of honey on his way to deliver it. His executive functioning is yet to develop. All of us at birth are stupid and greedy but also loveable. Milne himself described this quality of children as ‘brutal egotism’, but always combined with natural innocence.

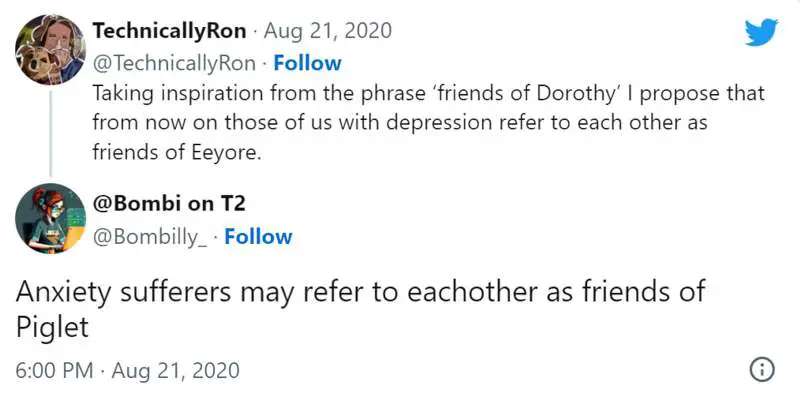

- The characters of the Pooh stories can be viewed as a ‘collective protagonist’ (from Jungian thought), with each character representing faults and virtues particular to some adults and some children, but Pooh himself (the hero) has faults and virtues common to children.

- Although slow, Pooh always comes through in an emergency. It is Pooh who rescues Roo when she falls into the river. Later he rescues Piglet.

- The characters are introduced gradually, one or two at a time in each story, which is like a child’s gradual discovery of their own traits.

- Pooh is the bland, confident, mystic child.

- Piglet is the small, nervous but very brave child. Piglet moves in with Pooh, which might be seen as a fusion of character. Piglet eats acorns. Piglet is used to mock cowardice.

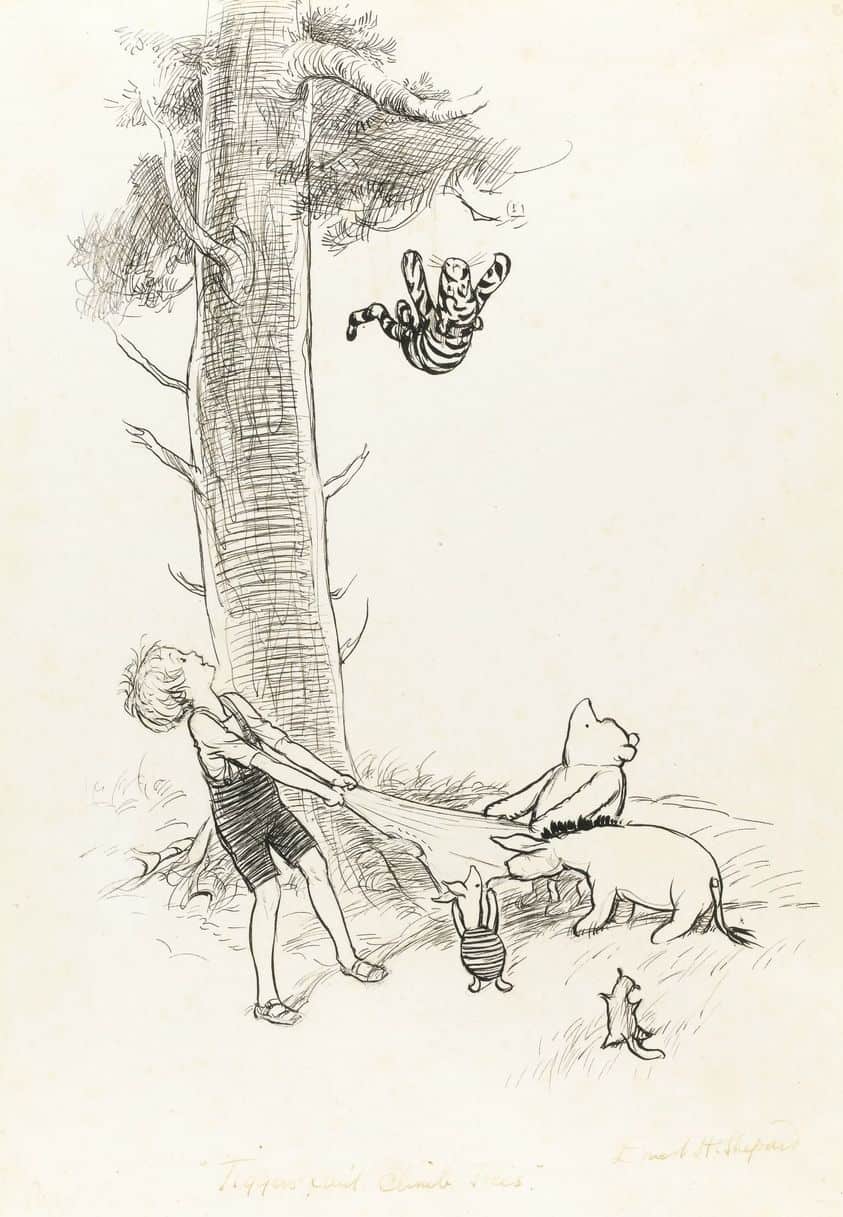

- Tigger is the wild child. He is fussy about his food. His attempts to find suitable food for himself is a search for identity. He must find his place in the hierarchy of the Forest (remember, the Forest equals childhood). Tigger is the only animal who doesn’t have a house of his own and stays with Kanga. This emphasises his smallness. (Not his physical dimensions but his general bouncy demeanour, which is childlike.) Normally — if he were a real animal — he would have gobbled up Kanga. This further disarms him. He is at the ‘pre-mirror’ stage of child development, and doesn’t recognise his own reflection. He is a baby who has just been weaned, tasting his mother’s different foodstuffs. Milne uses Tigger to mock verbal hypocrisies of greed.

- Roo is the baby, and critics find it difficult to say much interesting about Roo.

- Rabbit often thought to represent is the egocentric, sarcastic adult. Rabbit is the most conservative part of the collective protagonist. He is against change. He wants to get rid of Kanga and then Roo, then Tigger. But Rabbit is also the most childish. He is the most reluctant part of the child. This is a stubborn child who has made up his mind and is unwilling to change. (Perhaps he is really a very old man.) Rabbit is used to mock polite etiquette.

- Owl is the pretentious and insecure egocentric adult.

- Kanga is the loving but firm mother.

- Eeyore — together with Owl, Eeryore is closest to the world of adults. This is partly symbolised by his food. Eeyore eats thistles, rather than the sweet foods of childhood.

- Christopher Robin is small, powerless and oppressed. While Pooh is the child as hero, Christopher Robin is the child as God. He has the function of deus ex machina in the stories, stepping in to save the day. He is the ideal parent. He is both creator and judge — the two divine functions shared by mortal parents. He does not participate in most of the adventures but usually appears at the end of the chapter, sometimes descending with a machine like an umbrella, a popgun etc to save the situation. But Christopher Robin is never focalised, whereas all the other characters are.

“Was that me?” said Christopher Robin in an awed voice, hardly daring to believe it.

“That was you.”

Christopher Robin said nothing, but his eyes got larger and larger, and his face got pinker and pinker.”

- Milne’s work contains hidden messages. He pretends not to understand long words and makes fun of people who use them.

- He employs a special form of punctuation, capitalising words usually written with a lowercase letter — in the latter half of the 20th Century this was done in theatrical and film publicity, but is now done frequently on the Internet, often to mock the thing that has been capitalised. The subversive side effect of capitalising common nouns is to weaken the words and by extension the things that they stand for.

- When Milne uses a word it means what he tells it to mean. ‘Expeditions’ and ‘Bears’ mean something specific to the world of the story.

ABSENCE OF THEME IN WINNIE THE POOH

- ‘The Pooh stories are as totally without hidden significance as anything ever written.’ – Rowe

- See: The Pooh Perplex, which is a satire of literary criticism. The Pooh books were perfect for that, since they don’t seem to stand up well to such criticism.

- However, that doesn’t stop modern critics having a go. “The usage of Winnie the Pooh as a symbol of resistance should be studied and analysed by #folklorists is an actual tweet that lately came through my feed. Someone replied, “Wait, this is really a thing? 15 years ago, when France voted against LePen, I saw someone holding a giant Pooh bear at a celebration — I would love to know more!

Notes above are from

- From Mythic to Linear: Time in Children’s Literature by Maria Nikolajeva

- Written for Children by John Rowe Townsend

RELATED LINKS

The Ecology Of Winnie The Pooh, from Aeon

From The Hundred Acre Wood To Midtown – Winnie The Pooh in New York from Scouting New York

A catchy seventies song by a couple of guys with awesome shiny hair. It’s called Pooh Corner.

Celebrating Winnie-The-Pooh’s 90th With A Rare Recording (And Some Hunny) from NPR

Five Hundred Acre Wood: The forest that inspired Winnie-the-Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood can be found outside London from Atlas Obscura

A.A. Milne was never particularly proud of his Winnie the Pooh books, always aspiring to see success in writing for adults. Nor did he especially enjoy children, though he’s not alone in that. A lot of the most beloved children’s writers did not like children — rather, they seemed to write to revisit the child within themselves.

How to sound as if you might have been reading the Complete Works of Winnie-the-Pooh

When naming anything, start with ‘in which’. ‘In which I write to thank you for the Birthday Present’, ‘In which I resign from my job’, ‘in which you receive my condolences’, etc.

Use German-esque capitalisation mid-sentence for words considered Psychologically Important.

Keep nothing but various jars and pots of honey in your larder. Complain regularly about low-blood sugar. Honey needs to be spelt ‘Hunny’.

Don’t eat cheese because you don’t like it.

Move to the forest, rather like the British version of a TEA Party separatist. Good luck finding a forest in Britain, however, as no one has been able to find more than 4 miles square of forest since the ten hundreds.

When asking a favour of anyone say, ‘Could you very sweetly?’

Be a young-earther, and use phrases such as, ‘Once upon a time, a very long time ago now, about last Friday…’

Carve ‘Trespassers W’ into a plank of wood and nail it to your front fence.

Start talking to yourself but only in rhyming couplets.

When making philosophical statements, begin by saying, ‘It all comes, I suppose, of…’ or ‘If I know anything about anything…’

When someone doubts your wisdom on any point, say, ‘You never can tell with X’.

Use the gerund to make new nouns, even if perfectly adequate nouns already exist e.g. ‘a remembering’ instead of ‘a memory’.

You do not do ‘yoga’ or ‘warm-ups; from now on you do your Stoutness Exercises. As you do these you sing ‘tra-la-la-la-la’.

Give up swearing. Replace with ‘Help’, or for truly dire situations, ‘Help and bother’. Or you might like to run about saying, ‘Oh dear oh dear oh dear’.

Direct confrontions are out and should be replaced with passive aggressive retorts; ‘It all comes of eating too much. I thought at the time that one of us was eating too much, and I knew it wasn’t me.’

We do not go to the butchers’; we instead go hunting for Woozles or Heffalumps.

Lunch time shall henceforth be known as ‘luncheon time’.

If you have lost something, rather than look for it, stand around looking gloomy saying ‘Wherefore?’ and ‘Inasmuch as which?’ and ‘Why?’

A donkey’s tail makes a fine bell rope.

Your biggest problem is inclement weather, or perhaps the wrong sort of bees.

If anyone disagrees with you, say, ‘You never can tell’.

Use ‘goloptious’ as an intensifier e.g. ‘a goloptious full-up pot of honey’

‘Jiggeting’ means to move around quickly e.g. an idea ‘jiggets about in the brain’.

If everyone forgets your birthday, wander about gloomily and feel very sorry for yourself.

Never give delicious foods as a birthday present as you are likely to eat it up yourself before it reaches its proper receiver.

A Useful Pot To Keep Things In is always a good present. Also, always keep balloons on hand. They come in useful for numerous things.

When writing down a plan of action, subheadings are: General Remarks, More General Remarks, Therefore, A Thought, Another Thought and so on. Applies to writing minutes of meetings, if you’re ever asked.

Expeditions shall henceforth be known as ‘expotitions’.

Find a pole, any pole, and stick a sign to it saying ‘North Pole Discovered by [Your Name]. [Your name] found it.’

If it rains a lot, an umbrella can double as a rescue vessel. Or an empty jar of hunny.

The Every Little Thing podcast dived deeper than I thought possible into the questionable age (in years) of Winnie The Pooh. Is he a little kid, or an old man? I go through this same thought experiment with our 13 year old dog.

FURTHER READING

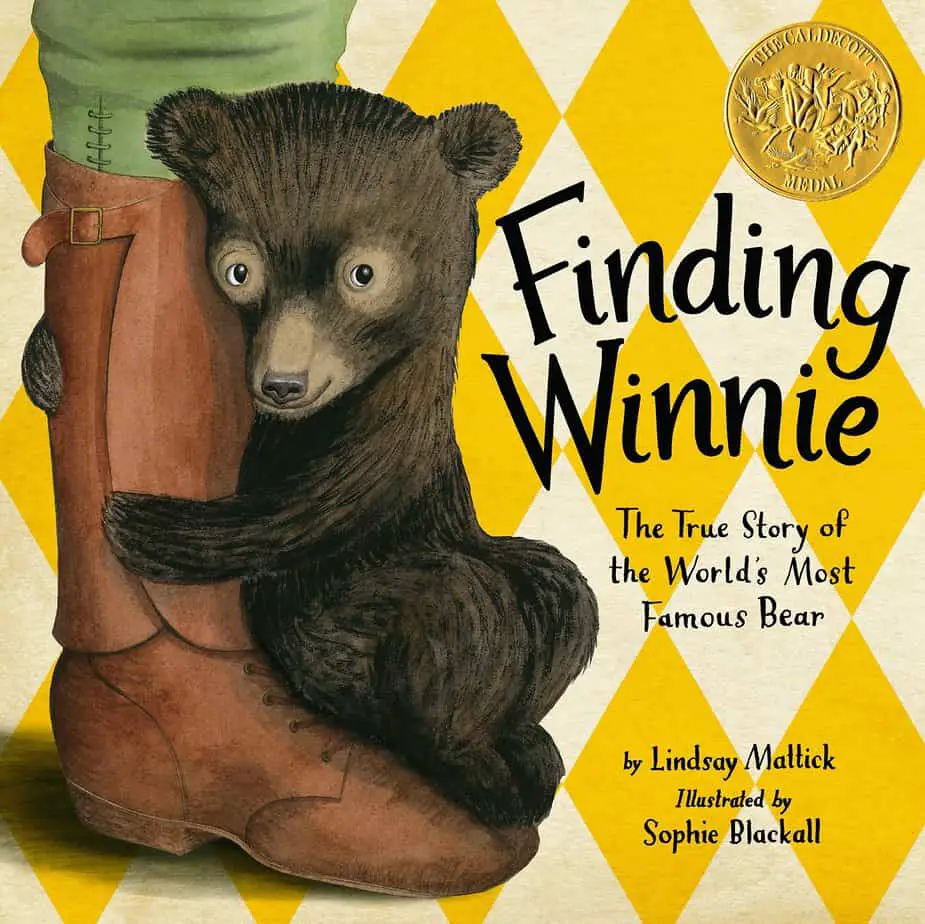

Before there was Winnie-the-Pooh, there was a real bear named Winnie.

In 1914, during World War I, Captain Harry Colebourn, a Canadian veterinarian on his way to serve with cavalry units in Europe, rescued a bear cub in White River, Ontario. He named the bear Winnie, after his hometown of Winnipeg, and he took the bear to war. Harry Colebourn’s real-life great-granddaughter Lindsay Mattick recounts their incredible journey, from a northern Canadian town to a convoy across the ocean to an army base in England . . . and finally to the London Zoo, where Winnie made a new friend: a boy named Christopher Robin. Gentle yet haunting illustrations by acclaimed illustrator Sophie Blackall bring the wartime era to life, and are complemented by photographs and ephemera from the Colebourn family archives. Here is the remarkable true story of the bear who inspired Winnie-the-Pooh.

A.A. Milne’s little books do not contain any blunt moral instruction, but there are plenty of lessons to be learned in the Hundred Acre Wood: the importance of friendship, the dangers of xenophobia, that even Very Small Animals can be brave on Blustery Days, and to not eat so much that you get stuck in a burrow. The other animals all look up to the wise Owl, though he misspells his own name, WOL. Reading this little irony, I look forward to the day my son can get the joke – but there is more to it than just a laugh. Later, Milne remarks on why Owl is so admired, “You can’t help respecting anybody who can spell TUESDAY, even if he doesn’t spell it right; but spelling isn’t everything. There are days when spelling Tuesday simply doesn’t count.”

There are days when spelling Tuesday simply doesn’t count. That’s what I really can’t wait for my son to understand. It’s something I find myself saying to myself almost every day now.

That’s woe transformed to joy, right there.

Why Children’s Books Matter