A Sock Is A Pocket For Your Toes (2004) is a picture book by Liz Garton Scanlon and Robin Preiss Glasser, published by HarperCollins.

A cave is a pocket for a bear,

a breath is a pocket full of air.

A hat is a pocket for your hair,

and a seat is a pocket called a chair…A Sock Is a Pocket for Your Toes: A Pocket Book is a whimsical pocket full of bells and balloons, ice cream and mud, giggles and hugs. Elizabeth Garton Scanlon’s delightful verse is captured in Robin Preiss Glasser’s energetic artwork, which follows four families through a busy day exploring the surprising ins and outs of the world’s pockets.

This special book will leave readers young and old with pockets full of joy!

MARKETING COPY

A Sock Is A Pocket For Your Toes is a picture book about all kinds of pockets. It helps readers to see the world in a different way. The author is working with the technique of defamiliarisation, though for young children, the whole word is unfamiliar. This is why young children are so good at this kind of lateral thinking already. Picture books such as this one help to preserve the inherent ability of young children to see the world in unconventional ways.

Learning a foreign language literally changes the way we see the world, according to new research.

Science Daily

THE ADVANTAGE OF MULTILINGUALISM

Knowledge of more than one language helps with this kind of lateral thinking. That’s because each language divides the world up differently. In Japanese, for example, the word for ‘toe’ is literally ‘foot finger’. It makes perfect sense, and is only funny once we transliterate it into English. Likewise, ankle is ‘leg neck’.

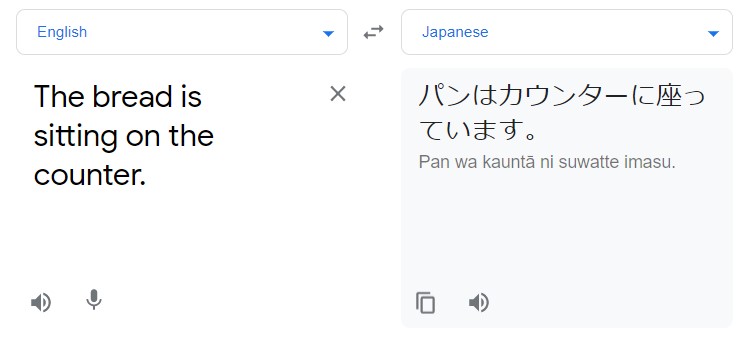

Likewise, there are English language concepts which sound hilarious in Japanese. In English we might say bread is ‘sitting’ on the counter. But the Japanese word for ‘sit’ has a narrower meaning, and refers only to creatures who have legs. (Clue: The kanji for ‘sit’ includes radicals for ‘person’, who are under the radical for ‘roof’. A radical is an element of a kanji which cannot be further broken down.) In Japanese, bread is simply ‘inanimately existing on’ the counter, not ‘sitting on’ the counter.

Anyway, this is why Google translate doesn’t work well at all between English and Japanese:

Google has translated my English sentence literally. If a native Japanese person heard that, they’d imagine anthropomorphised bread with legs dangling off the counter and they would probably laugh.

I can imagine that in other languages the word for ‘pocket’ is used more generically than it is in English. A Sock Is A Pocket For Your Toes imagines what English might be like if the word ‘pocket’ referred to a wider variety of things.

SEMANTIC WIDENING

In linguistics, when words evolve to include a wider variety of meanings it is called ‘semantic widening’. (The opposite phenomenon is semantic narrowing.)

Semantic change is the evolution of word usage. Semantic change is change in one of the meanings of a word. When features are dropped, this is called widening. Widening may result in either more homonymy or in more polysemy. Semantic widening broadens the meaning of a word. This process is called “generalization.” Some factors that affect semantic widening are linguistic factors, psychological factors, sociocultural factors, and cultural/encyclopedic factors.

Fandom

HOMONYMY: The adjective of homonym. Homonyms are two words that are spelled the same and sound the same but have different meanings.

POLYSEMY: The coexistence of many possible meanings for a word or phrase.

Companies who sell products which become popular are very familiar with the phenomemon of semantic widening. In America it happened to the brandname Kleenex (capitalised), and now kleenex (common noun) is the generic word for ‘disposable tissue’.

Lego doesn’t want their brand name to become the generic word for ‘toy building bricks’ due to semenatic widening. This is why publishers are legally required to capitalise if using it in, say, a children’s book. (Some publishers are very keen to avoid legal trouble and don’t allow words such as Lego in books at all. However, I have occasionally seen it.)

HOW TO WRITE A POEM PICTURE BOOK?

The secret to writing a picture book like this one is to go above and beyond the most obvious connections. This also applies to carnivalesque picture books, in which the storyteller goes one or two steps beyond reader expectations in order to surprise. There is a carnival aspect to this book. The children in the illustrations are having lots of fun and eating lots of delicious food.

The pocket metaphor begins with a list of concrete examples of containers, then eventually takes us into the abstract e.g. ‘A giggle is a pocket for a joke’.

This is exactly how words broaden their meaning. Look up the dictionary definition of, say, ‘table’ and first you’ll get the concrete noun: a piece of furniture with a flat top and one or more legs, providing a level surface for eating, writing, or working at.

This will be followed by the verb, which has clearly come from the noun.

More abstractly, then, ‘to table’ something is to place something on the table, or to suggest something. (At least in Britain. In America it means kind of the opposite, to leave something — on the metaphorical table — for later.)

THE ENDING

How to give a ‘sense of an ending’ in a picture book like this one, which is not making use of classic narrative structure? When we get to the line, ‘A pocket for a family is a home’, we know the story is drawing to a close. Many picture books take place over the course of a 12-hour day, so we are used to stories ending at this point. Now the reader is guided through a joyous evening routine of eating ice cream together on the verandah, brushing teeth, looking out of the window at stars and receiving hugs. The final line is: ‘My heart is a pocket full of love’.

WRITE YOUR OWN

If using this book in the classroom as mentor text, what other word might lend itself to semantic broadening in this way? The place to start is with words whose symbolic meanings are already widely utilised by storytellers (ie. universal symbols)

- hat: An X is a Hat For Your Y

- coat: An X is a Coat For Your Y

- house: An X is a House For Your Y

- fence: An X is a Fence For Your Y

- etc

FURTHER READING

This picture book has taken the word ‘pocket’ and widened its meaning to ‘container’ of any kind. See also: The Symbolism of Containers.

The header illustration is a 20th century advertisement for interwoven socks, illustrated by Norman Rockwell.

THEY HAVE POCKETS