Recently the Woman’s Hour podcast talked about a gendered comedy trope which I’d never really noticed was gendered: the socially aspiring, snobbish female.

Hyacinth Bucket is a standout example, along with:

- Linda Snell from The Archers

- Audrey fforbes-Hamilton from To The Manor Born

- Margo from The Good Life (Penelope Keith is especially good at playing these characters)

- Hyacinth Bucket (pronounced Bouquet) from Keeping Up Appearances

- Sybil Fawlty from Fawlty Towers

- Doreen from Birds of a Feather

In literature, Britain has several archetypal socially climbing women:

- Becky Sharp from Vanity Fair

- Mrs Bennett from Pride and Prejudice

These women living in the 1800s had no choice but to be socially climbing, because for them, living in a patrimony, marrying well was a matter of life or death.

Although the trope is very old, the socially climbing female a little out of fashion at the moment. Note that those sit-com examples listed above are concentrated in the 1970s and 80s.

The standout modern example in England right now is Pauline from Mum, written by Stefan Golaszewski, who grew up on those older sit-coms. However the tone of Mum is quite different. Margo can laugh at herself on The Good Life, but Mum is ‘impenetrable’.

We do still see them as a part of a wider cast in a show starring a different kind of comedic character. Fleabag’s step mother (from Fleabag) is another modern example of the socially aspiring woman.

You tend to see these women in the following situations:

- She affects an accent which she perceives to be higher class, but gets it wrong.

- She is completely self-absorbed and blind to other people’s wishes.

- Her fashion choices are over the top, whatever that means for her milieu. Her choices are perceived by the actual powerful class as kitsch (‘stuff other people unaccountably like’)

- There will be something about her home environment which stands out as very ‘her’. With Hyacinth it is her home decor, full of flowers and perfectly dusted. She’s often holding a duster.

- There will be a skeleton in the closet which comes off in each episode to great comedic effect. This is the ‘mask coming off’ comedy trope.

- If she’s a mother she’s either overbearing or distant.

- This is a white and heterosexual archetype.

- If she’s married, her husband is henpecked and mild-mannered.

- She is disgusted by people who she perceives as lower rank than herself.

- These women strive to be powerful (that’s their Desire) but they are not in fact powerful. They therefore surround themselves in people who are less powerful than themselves. They may have a kind of lackey best friend.

- As you can probably tell, her psychological shortcoming and moral shortcoming is perfectly set up and inherent to the trope — she feels inferior and she steps all over others in an attempt to rise above her own station.

- This lackey best friend (or neighbour, or sister) will be a ‘see saw’ character, who is very, very nice and a people pleaser. Other people pleasers are vicars, postmen, people working in service industries, and they all tend to crop up to allow this woman full comedic flight. It’s not as fun to watch her come up against someone with more power than herself because we don’t really want to see her get quashed, but in a show such as To The Manor Born, it is satisfying to see Richard, with far more actual power, afford her a certain respect.

- It may be necessary for the audience to feel a little sorry for these women, in lieu of actively ‘liking’ them. We will usually be shown her ‘behind the scenes’ self. That might be the character without her make-up, with her hair looking wild; her poor relations; her economically destitute situation.

- The archetype rests upon the stereotype that women are impossible to please; flighty, capricious — for husbands there is ‘no winning’. These women are insatiable, unable to be satisfied, so you shouldn’t even try. Pacifying her is your best bet. This stereotype can be deployed with much malice or less — the degree of sexism depends partly on how it is written.

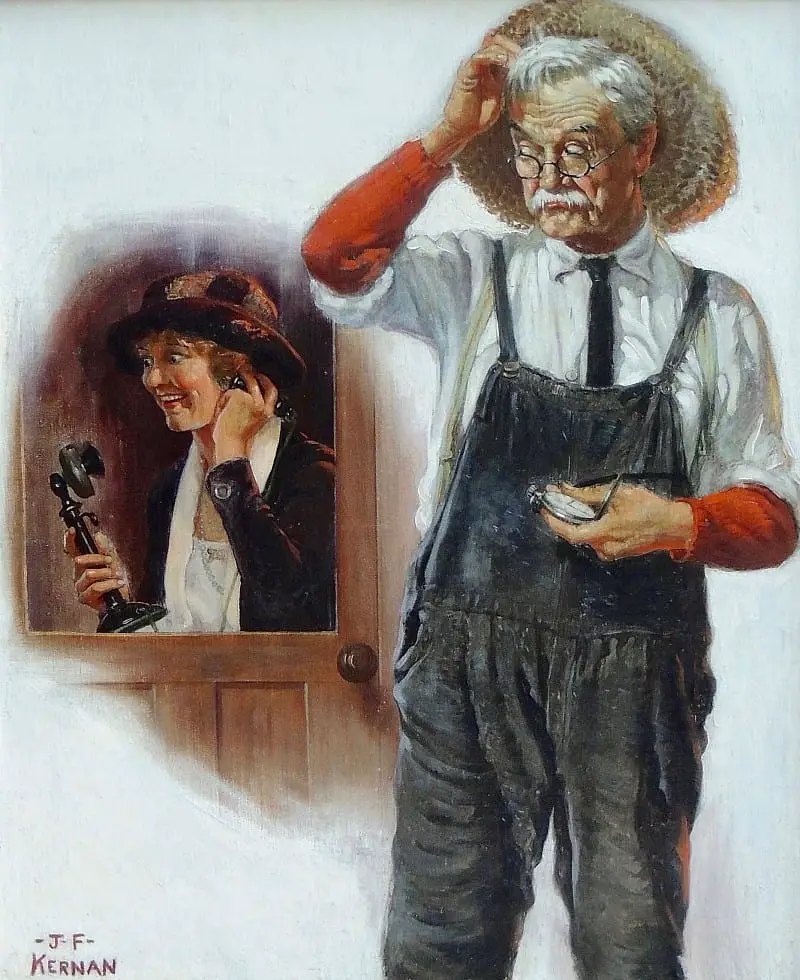

- She is commonly depicted as gabbing into the telephone. This plays on the wider cultural idea that women and telephones make natural companions, because women do love to chat! Hyacinth Bucket and Sybil Fawlty are frequently depicted using the telephone. In both cases, the telephone is associated with a memorable catch phrase, “Oh I knoooow!” and “It’s Bouquet.”

Despite the prevailing view that talking by telephone was frivolous, and favoured by women, the telephone became a key technology the telephone became a key instrument in keeping people connected during the outbreak of the Spanish flu in 1918-1920. Initially seen as a luxury, the telephone quickly became a necessity.

THE SOCIALLY ASPIRING WOMAN IN AUSTRALIA

Australian audiences understand this comedy trope perfectly. Our own standout example is Kim from Kath and Kim. Kim is stupid rather than wily, which is what keeps her in her position of no power.

However, it is said on Woman’s Hour that this trope is a specifically British one which we don’t really see much in America. The closest example they could think of was Monica from Friends, who aspires to have everything tidy, but it’s not really the same thing.

THE SOCIALLY ASPIRING WOMAN IN AMERICA

Why don’t we see much of this woman as a comedy trope in America? Probably because social climbing is actively encouraged. Why would you not aspire to have more capital, economically, socially and otherwise?

I do think America has a related trope: the woman who wants to be more sexually alluring than she is perceived by those around her. It’s the Bouquet/Bucket dichotomy only in relation to sexuality. This gag only works if the woman in question is not perceived by the audience as sexually alluring, in the same way the Bucket joke doesn’t work unless we all read B.U.C.K.E.T. as ‘bucket’. The actress who plays her cannot conform too well to the Western female beauty standard.

Sometimes the character is indeed sexually alluring by everyday standards, but that’s the only nice thing about her. Every other attribute is exaggeratedly terrible. Regina George from Mean Girls is the stand out example of that. We see this archetype in British comedy as well, for example Jen’s insistence on wearing too-small shoes in The I.T. Crowd.

However, I do think America is starting to embrace this comedic archetype, perhaps because the culture is starting to question the American story that everyone can rise above their station given enough work.

I’m thinking of Moira Rose of Schitts Creek, whose accent is a comedic affectation. This character considers herself queen of the town despite being widely disliked. However, Moira Rose does have an admirably wide vocabulary:

Moira owns a vast collection of precious wigs, which is the classic trope of putting a headdress on yourself as a ‘crowning’ glory. Moira is a very camp character as well — she revels in putting on ‘the mask’, and knows exactly what she’s doing. Someone like Hyacinth Bucket doesn’t seem to realise she’s wearing a mask at all.

Perhaps Moira Rose is the modern, ’empowered’ version of the socially aspiring woman: she has no power, but she takes it anyway, knowing no one is about to give it to her for free.