“Snow White and Rose Red” exists in many forms but I’ll refer to a version set down by the Grimm Brothers. This is the story of a lesser known Snow White, and her sister Rose Red. There is indeed a dwarf, but he’s a different sort of dwarf from the crew we encounter in Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

If you’d like to hear “Snow White and Rose Red” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Snow White and Rose Red” was published March 2019.

SETTING OF “SNOW WHITE AND ROSE RED”

How big is this utopian forest? The girls keep running into the dwarf. I put it to you that this is either a tiny forest (more like a spinny) or they meet a different dwarf each time. (Turns out dwarves keep changing in size.)

Either that or the girls are stalking the dwarf. Perhaps they are not as stupid as they appear on paper, and were in on the bear’s plan from the get-go, hoping to kill him themselves, but only after he reveals his store of treasure.

None of this is on the page, of course, because fairytales as recorded by the Grimm Brothers rendered girls and women innocent naifs who required rescuing by men.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “SNOW WHITE AND ROSE RED”

Snow White belongs to a category of stories in which girls are taught self-sacrifice in order to better serve men. These stories didn’t stop appearing in the 1800s. More recent examples:

- The Tale of Mrs Tittlemouse by Beatrix Potter (1910)

- The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein (1964)

- The Very Cranky Bear by Nick Bland (2008)

In “Snow White and Rose Red” an ursine prince asks to come in and warm by the fire. Of course the women let him in, as Mrs Tittlemouse let in the toad, also to sit in front of her fire. Because he wanted to. Because he believed he had the right to her space, her time and her attention. And because the girls fulfilled their feminine roles of caring, all worked out in the end.

SHORTCOMING

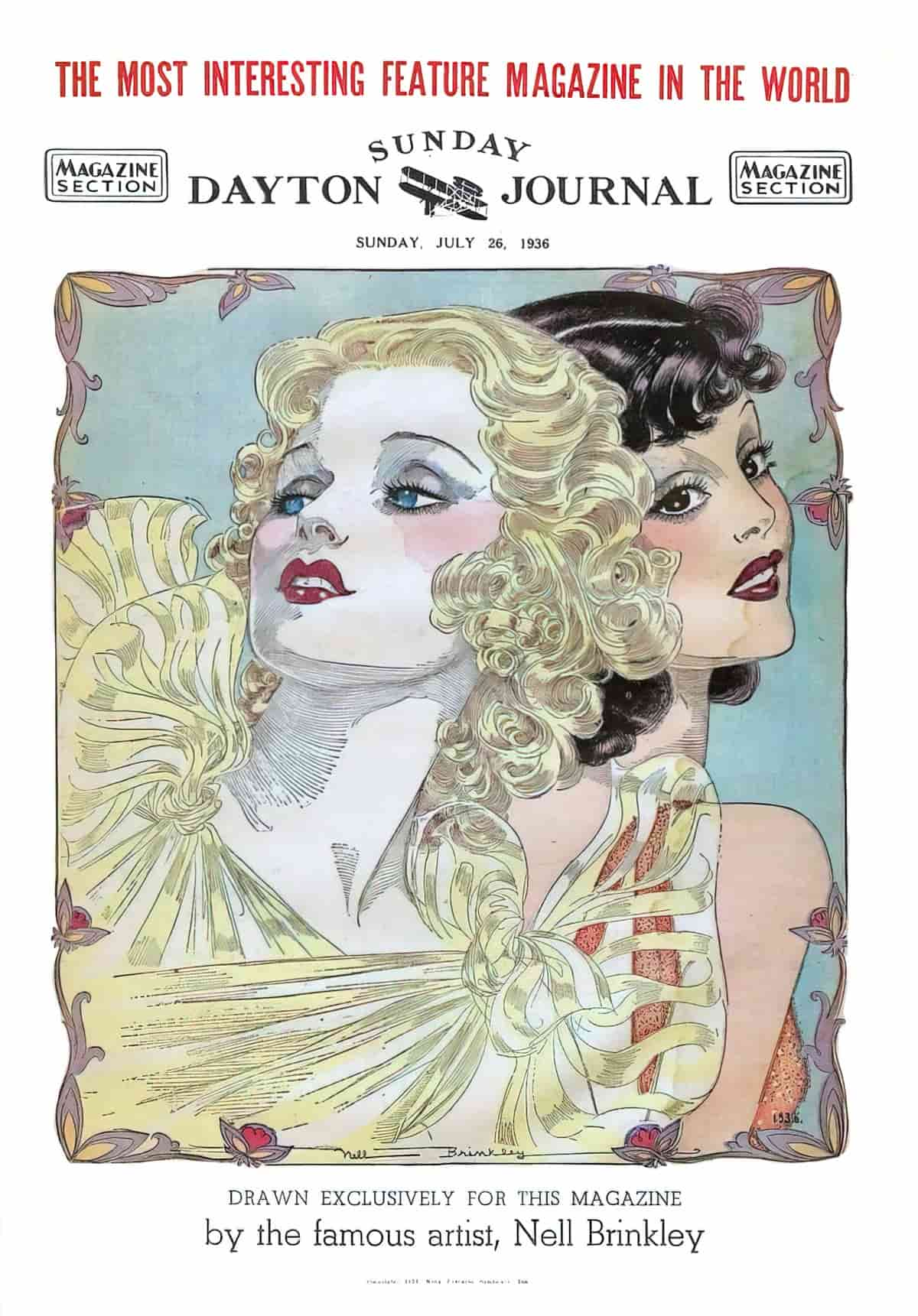

This is the story of sisters, presented as different sides of the same coin. Any personality difference is symbolised by the contrasting colour of their hair.

These archetypes have been recycled in many stories, for example in Laura and Mary from the Little House series, or Anne and George from The Famous Five series. One is quiet, the other active:

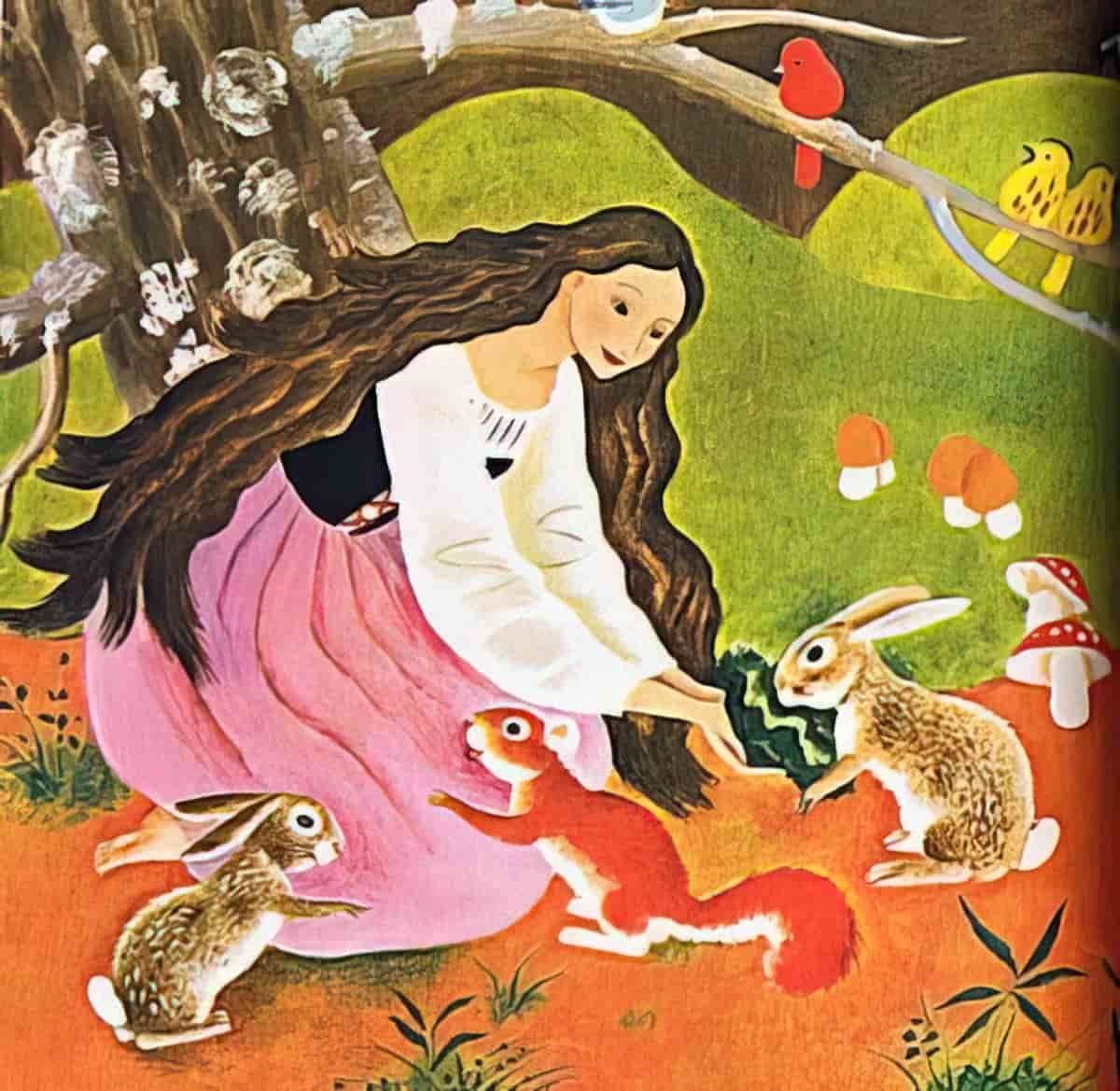

Snow-White was more gentle, and quieter than her sister, who liked better skipping about the fields, seeking flowers, and catching summer birds; while Snow-White stayed at home with her mother, either helping her in her work, or, when that was done, reading aloud.

These are the Ideal Girls, at one with nature, loving each other deeply. They always share everything and are perfectly clean and tidy. They have no moral shortcoming at all.

In a way, Snow White and Rose Red have superpowers. They are high mimetic heroines according to the scale proposed by Northrop Frye. Their superpower is a specifically feminine variety. These girls are so well connected to Earth and nature that nature cannot harm them. The idea that women are close to nature both elevates and hinders women. If you’re close to nature, you can’t rise up to become one with God, unlike men, who are Gods of their own domains.

Because these girls are so Good, ‘no mischance befell them’. This exposes a problematic ideology in which bad things happen to bad people. So what, exactly, is their story worthy problem? How do we make a story out of that? When the main characters of a story are Mary Sue archetypes, all the interest must come from the opponents. What tends to happen is, the main characters are so boring the contemporary reader ends up empathising with the opposition, simply because they’re not boring. This is partly why Mary Sue characters are a bad idea in modern stories, except in parody.

DESIRE

Snow White and Rose Red live in Arcadia, where even at night in the surrounding woods are perfectly safe, and berries available whenever they’re hungry. What more could these characters want? They want for nothing, of course. This is part of what makes them so Very Good.

(It’s easier to want for nothing when all is provided for you.)

So any desire must come from other characters. The bear is the character with the strong desire for change, so the story kicks off when he enters the story.

OPPONENT

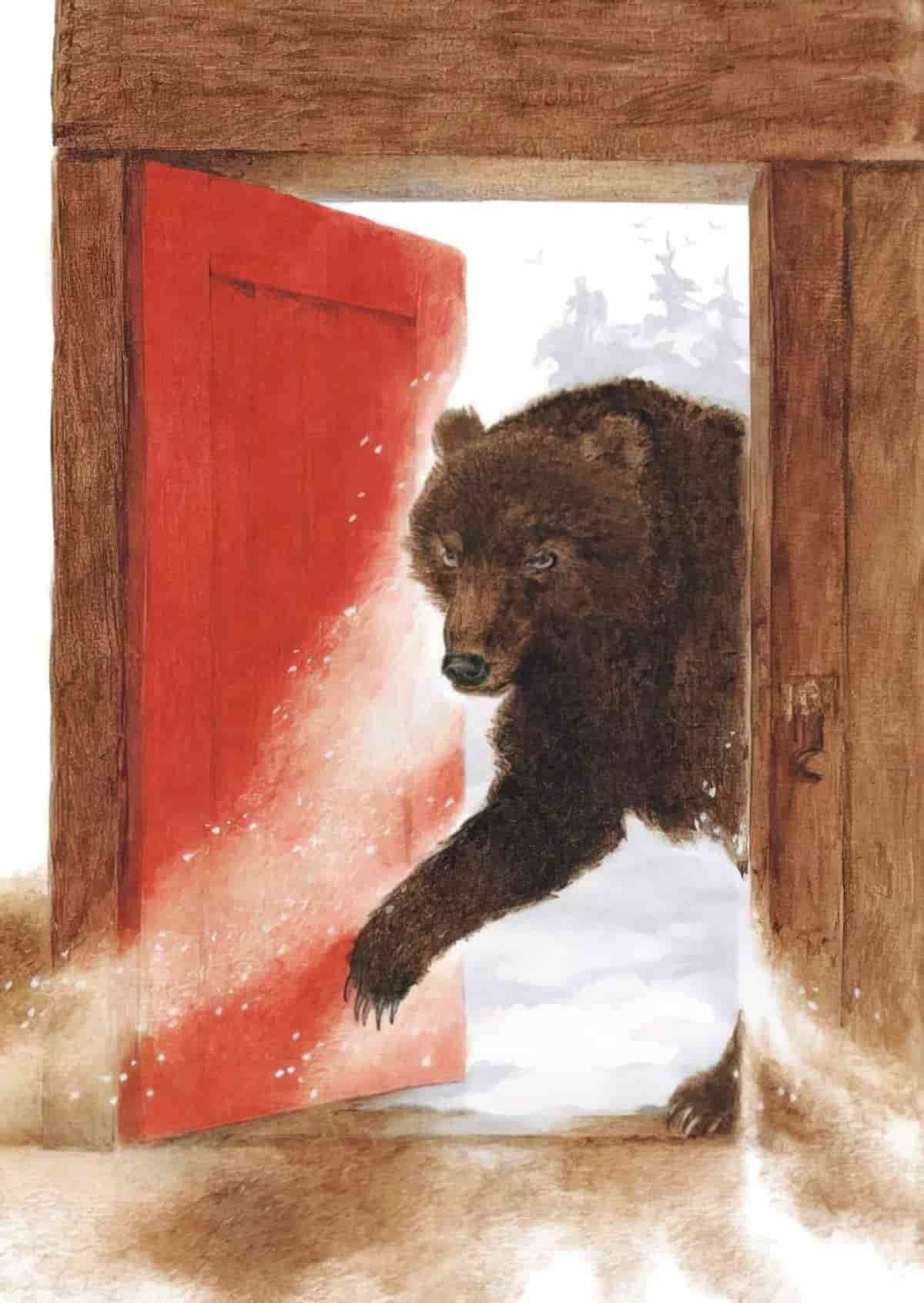

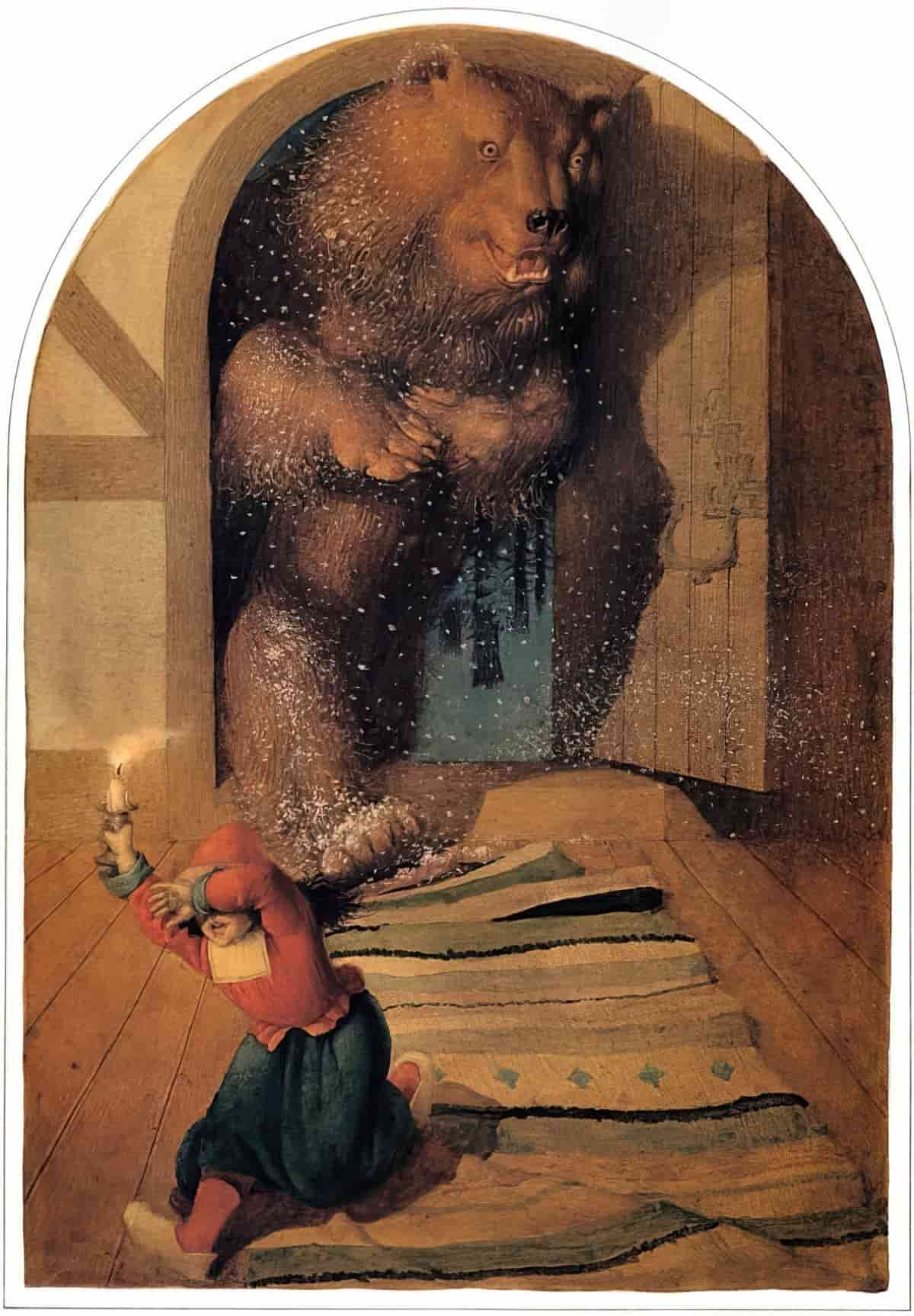

Adventure comes to the door of their idyllic, cosy cottage, inhabited only by three women (the sisters and their mother).

One evening, as they were all sitting cosily together like this, there was a knock at the door, as if someone wished to come in.

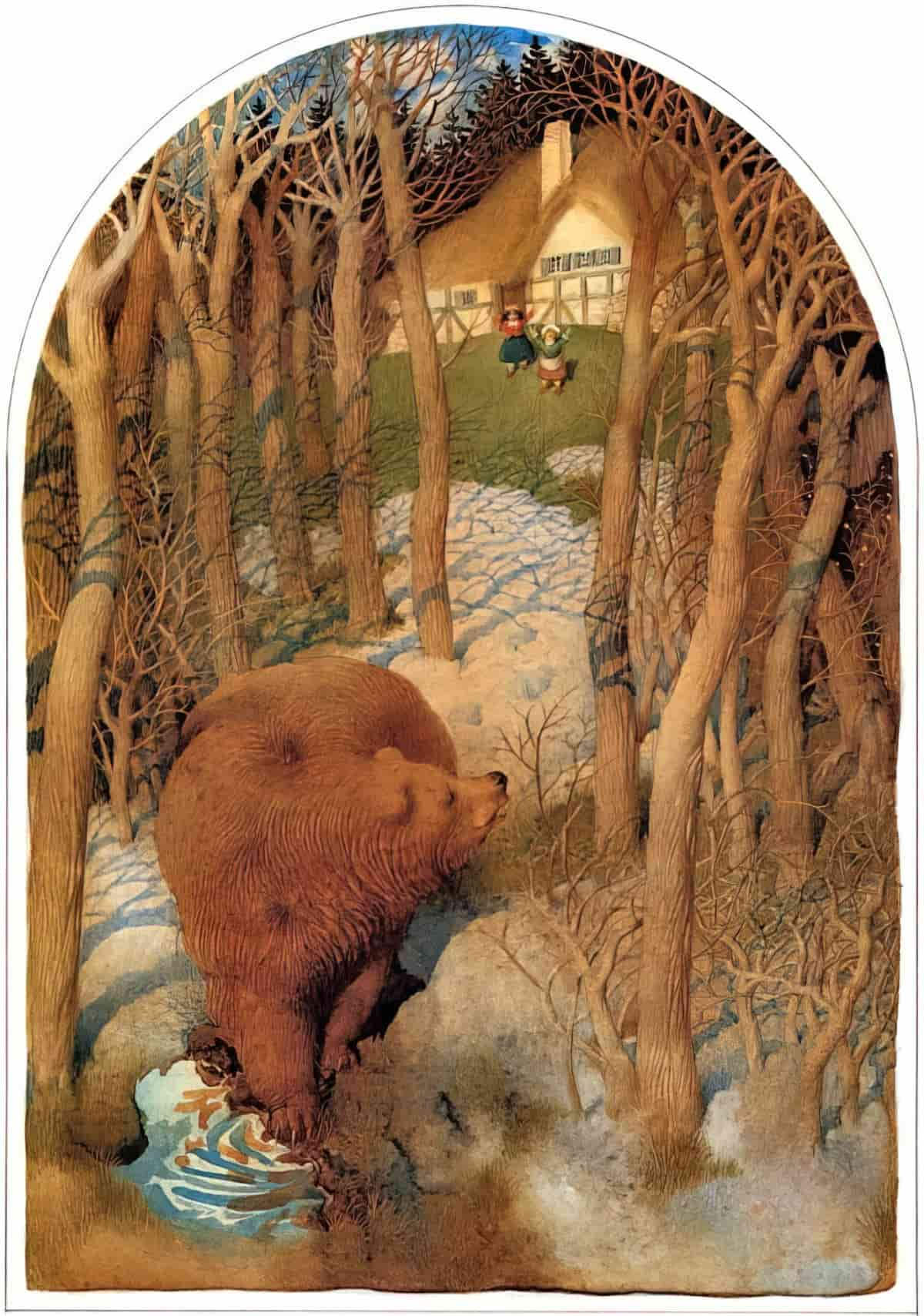

All but the youngest audience will understand that this is not a bear but a prince. He’s a talking bear. (The film Brave takes the bear transformation plot and inverts its gender by turning a queen into a bear. ) Readers convince ourselves we don’t know if he’s a goodie or a baddie, though his royalty status is telegraphed when he rips his fur on the lintel and a little bit of gold shines through. This is supposed to be a reassuring tale.

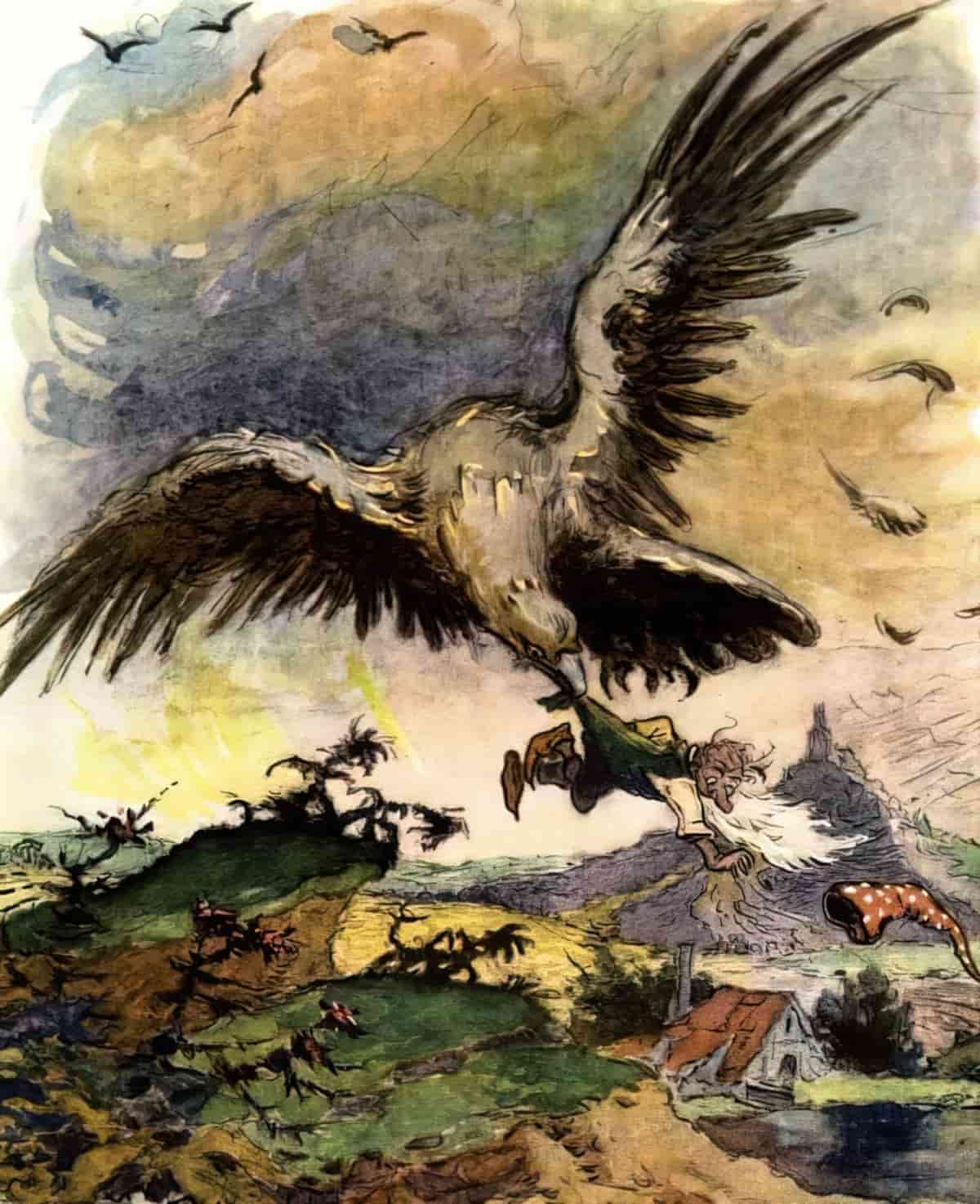

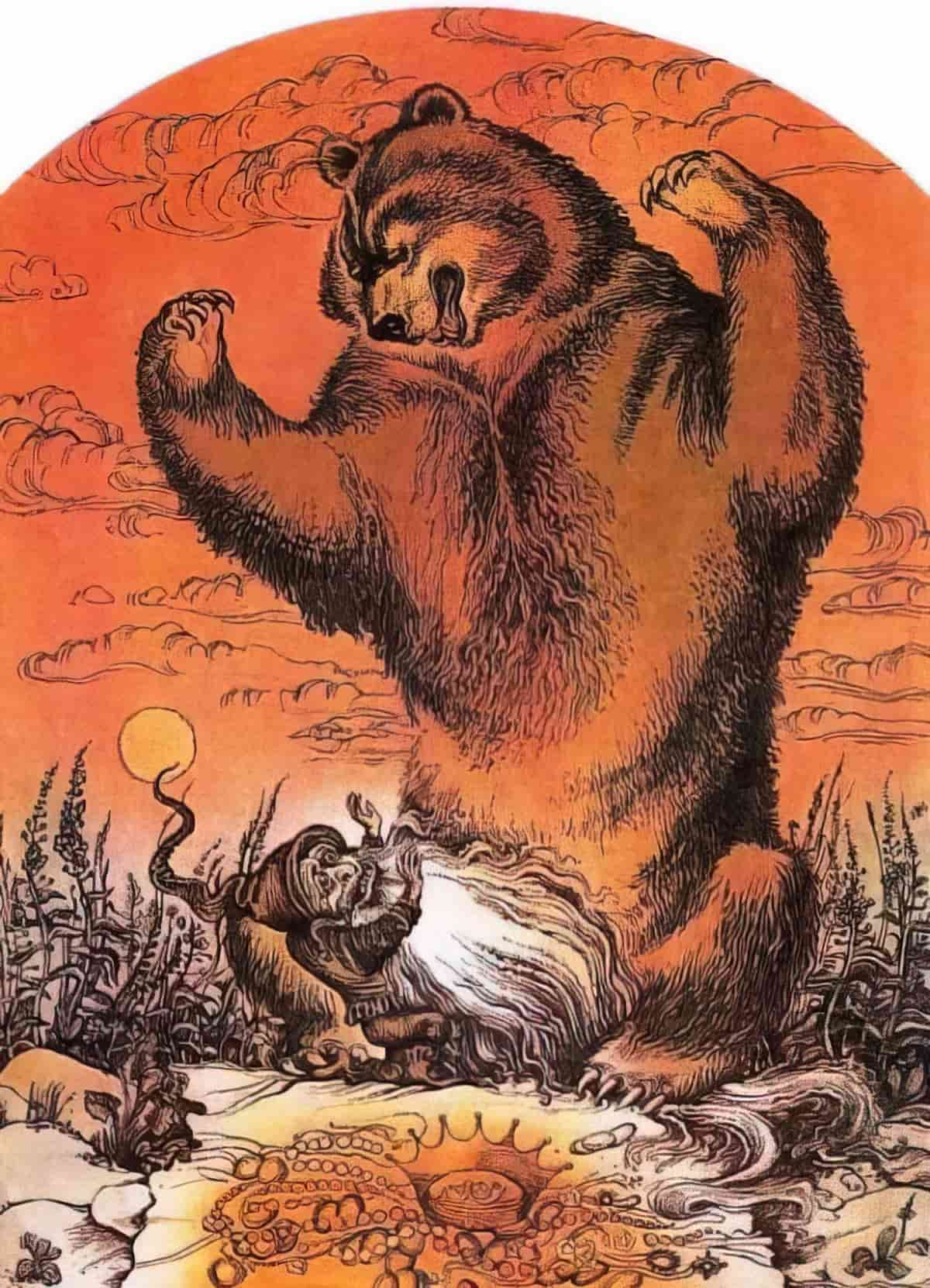

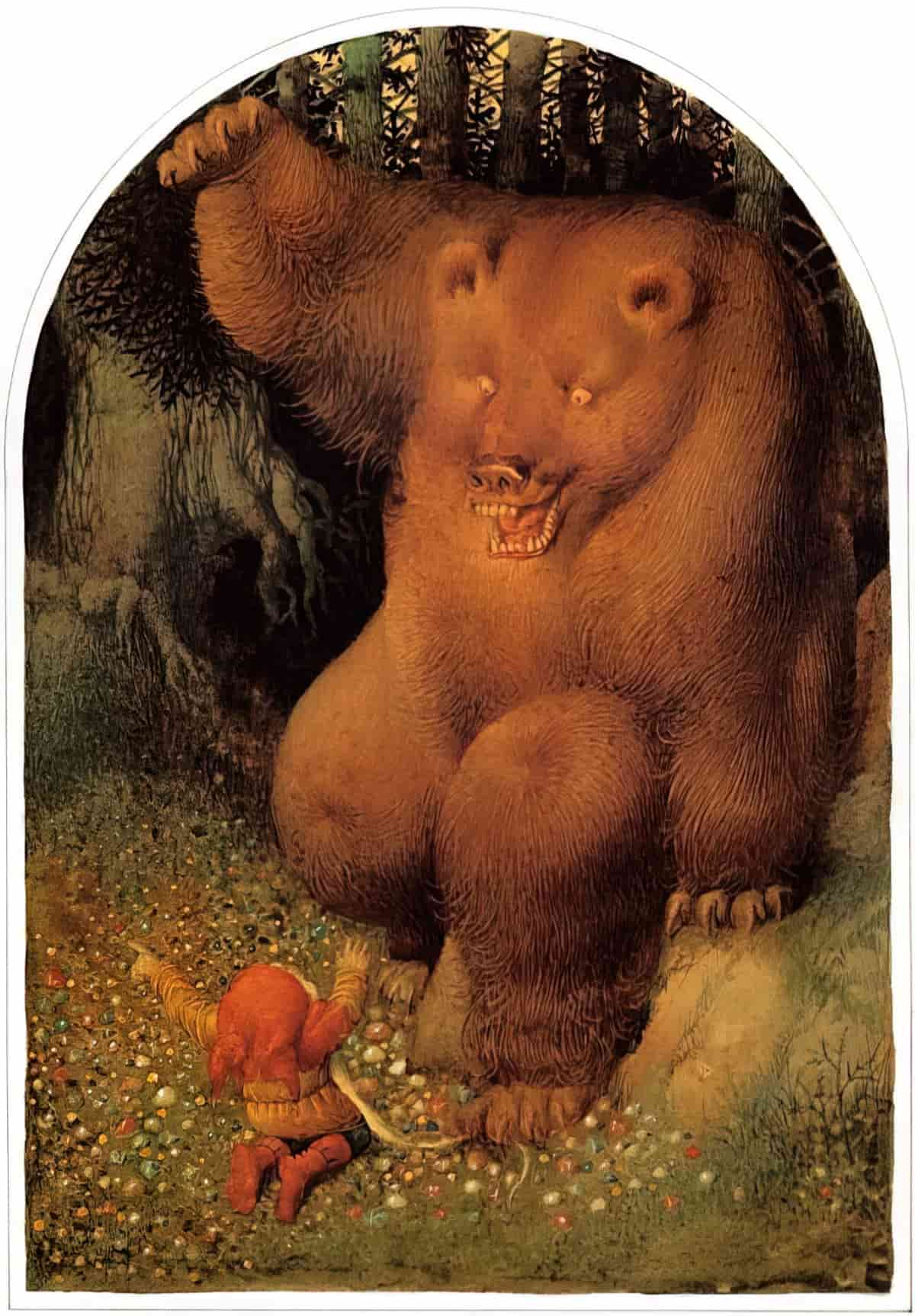

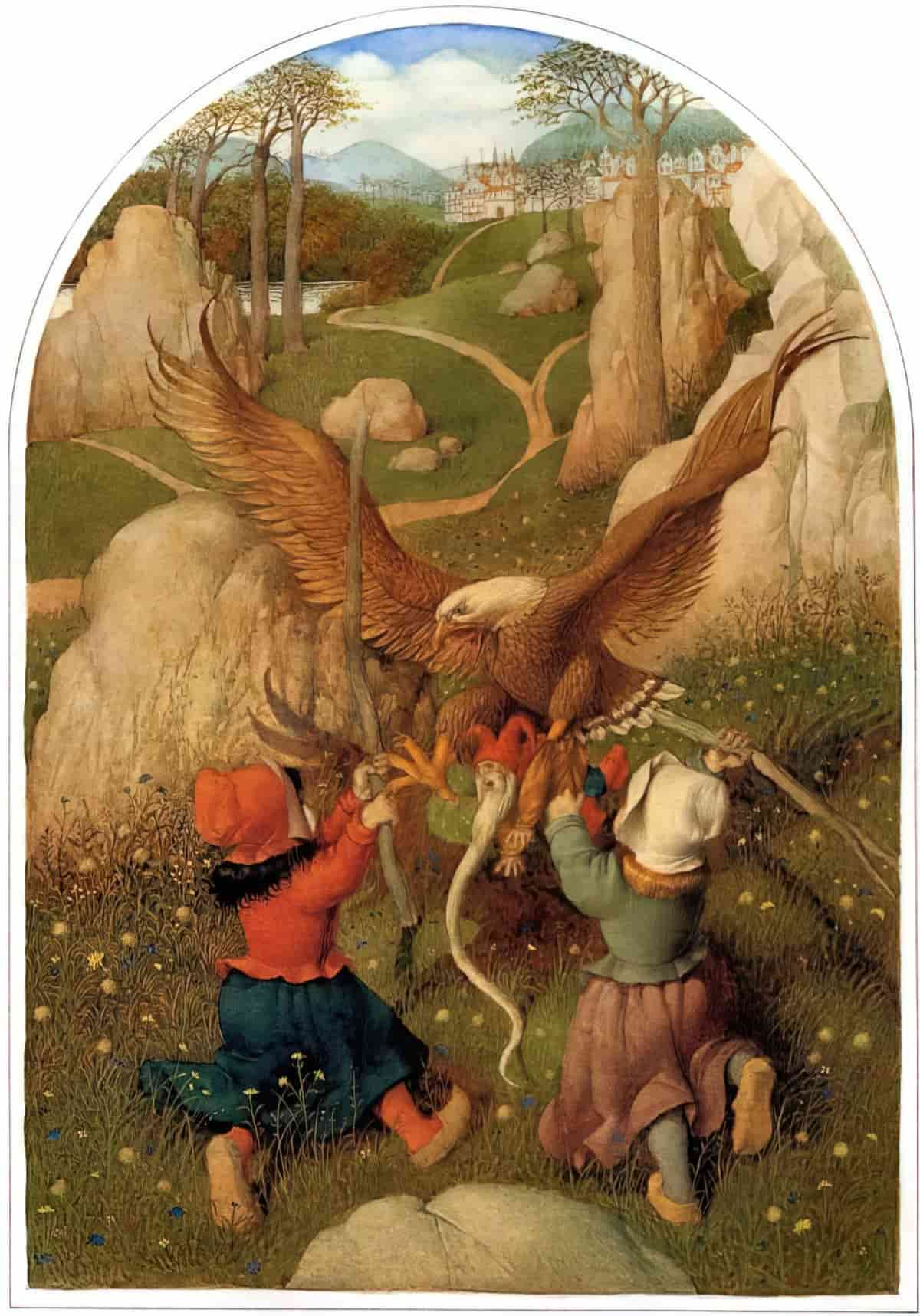

The dwarf is clearly a baddie from the start. If you’ve only ever read modern, illustrated versions of this story it’s a surprise to read the Grimm’s version and learn how very small he is at times. Case in point, the girls mistake him for a grasshopper at one point. In my childhood picture books he is almost half the height of the girls.

If you met someone cranky but they were not much bigger than a grasshopper, their rage wouldn’t really scare you, would it? On the other hand, the dwarf is able to pick up ‘a sack of jewels’. In fairytales, dwarves are as big or small as the story requires them to be at any given time.

THE SIZE OF THE DWARF

On that point, how big were fairies, dwarves and other small fantasy creatures really meant to be? That depends on where you come from and in what era you lived.

Elizabethans loved miniature creatures, and the Jacobeans even more so.

Take a creature like Oberon (fairy king). In one story he is three feet tall, in other he is the size of the King on a playing card. Take another fantasy creature, the witch’s familiar. In England the witch’s familiar is a very small creature like an insect or a bee, but in Scotland, familiars are also attached to magicians and are bigger, more powerful creatures. Take fairies. Before Shakespeare they are about as big as insects, similar to the English witch’s familiar. Shakespeare himself made his fairies ‘in shape no bigger than an agate-stone’.

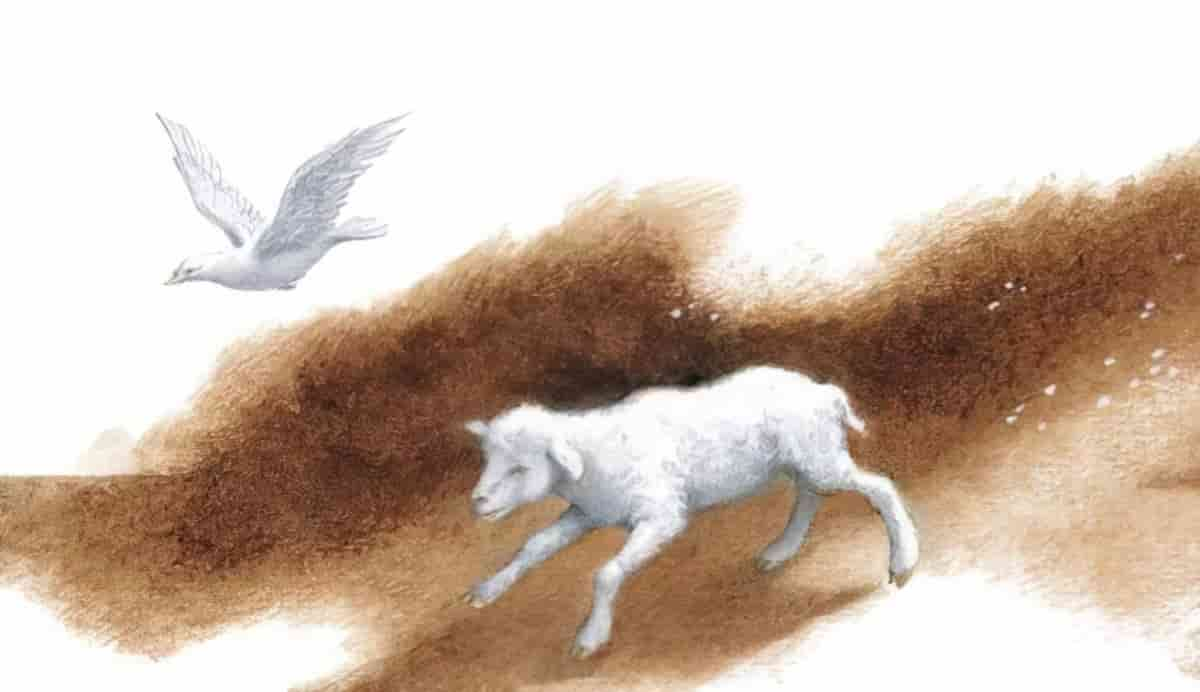

In this old tale, the dwarf is small enough to be picked up by a large bird.

The trope of the human picked up and carried away by a bird clearly plays into ancient fears.

PLAN

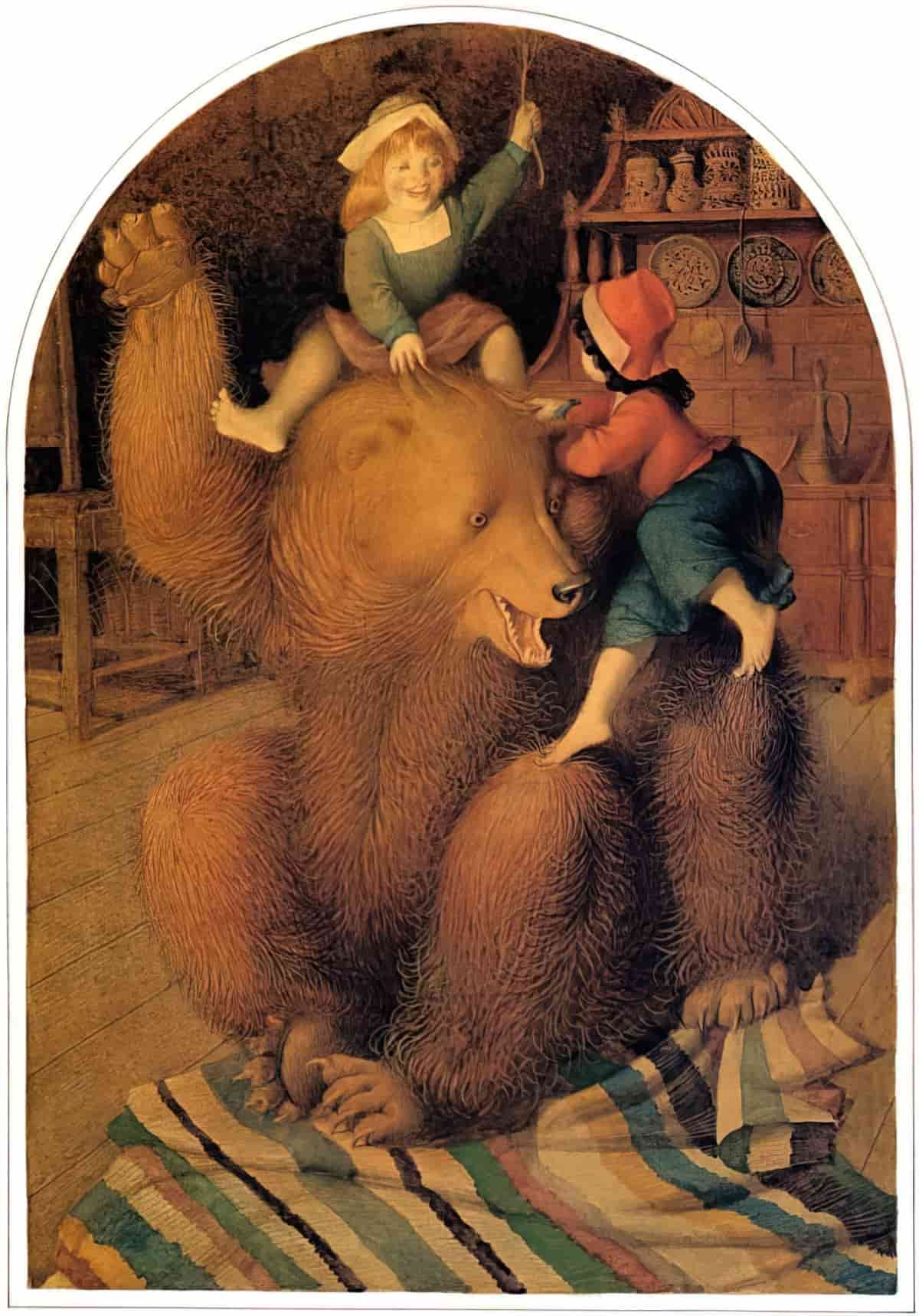

With no plans of their own due to living in a forest utopia, agency comes from the bear. Clearly he didn’t need to warm himself beside the fire. Bears are capable of thriving in very low temperatures. His plan from the start, revealed later, was to spend time next to the girls so that they’d fall in love with him. He is rewarded with rough and tumble and close physical affection.

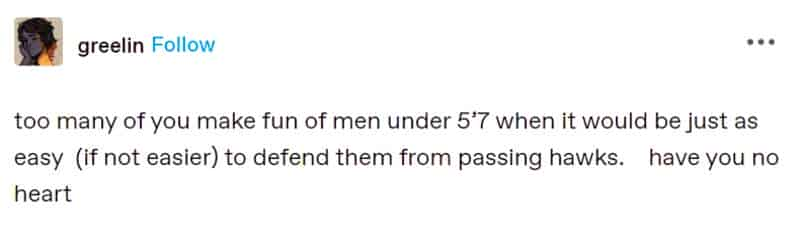

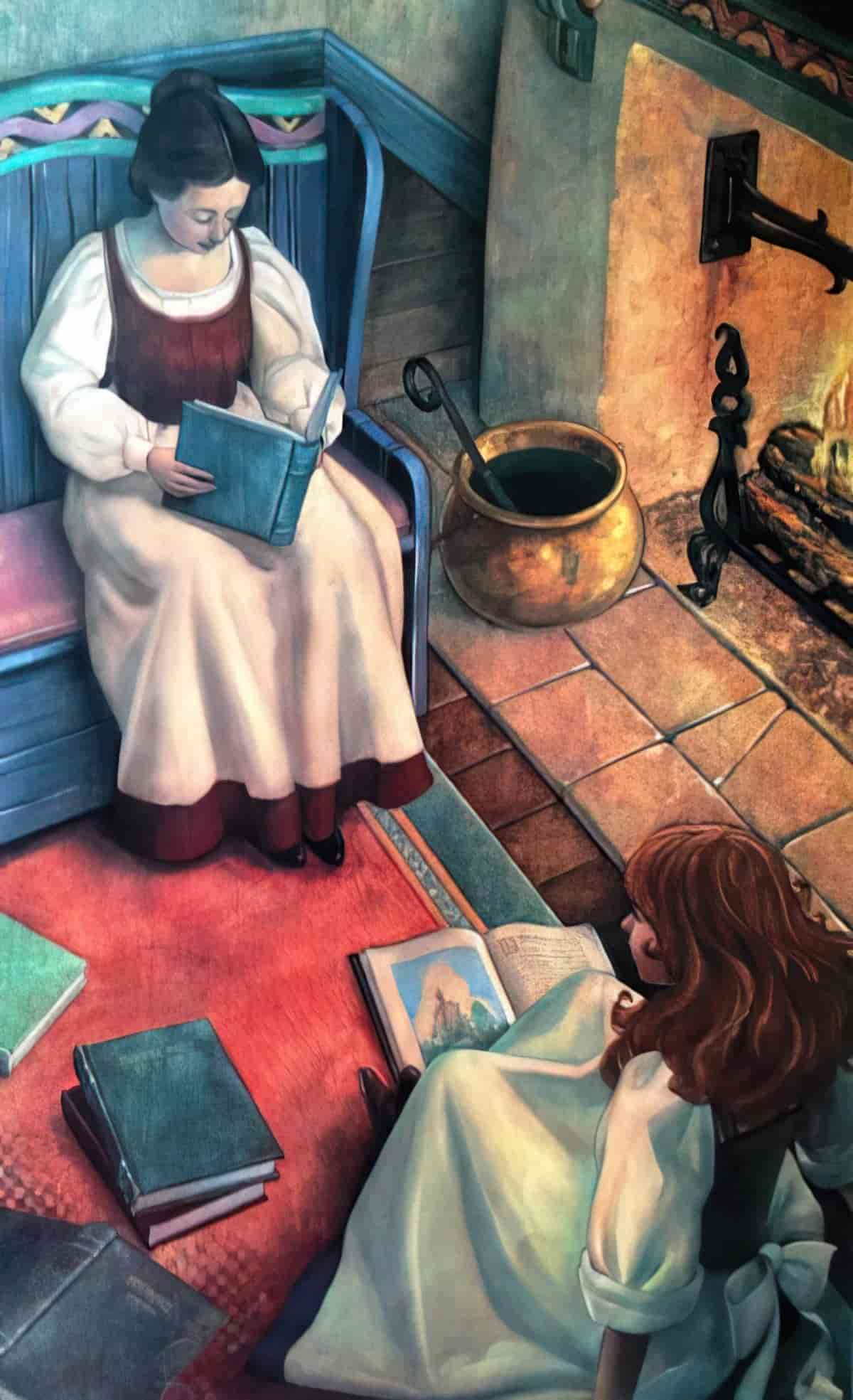

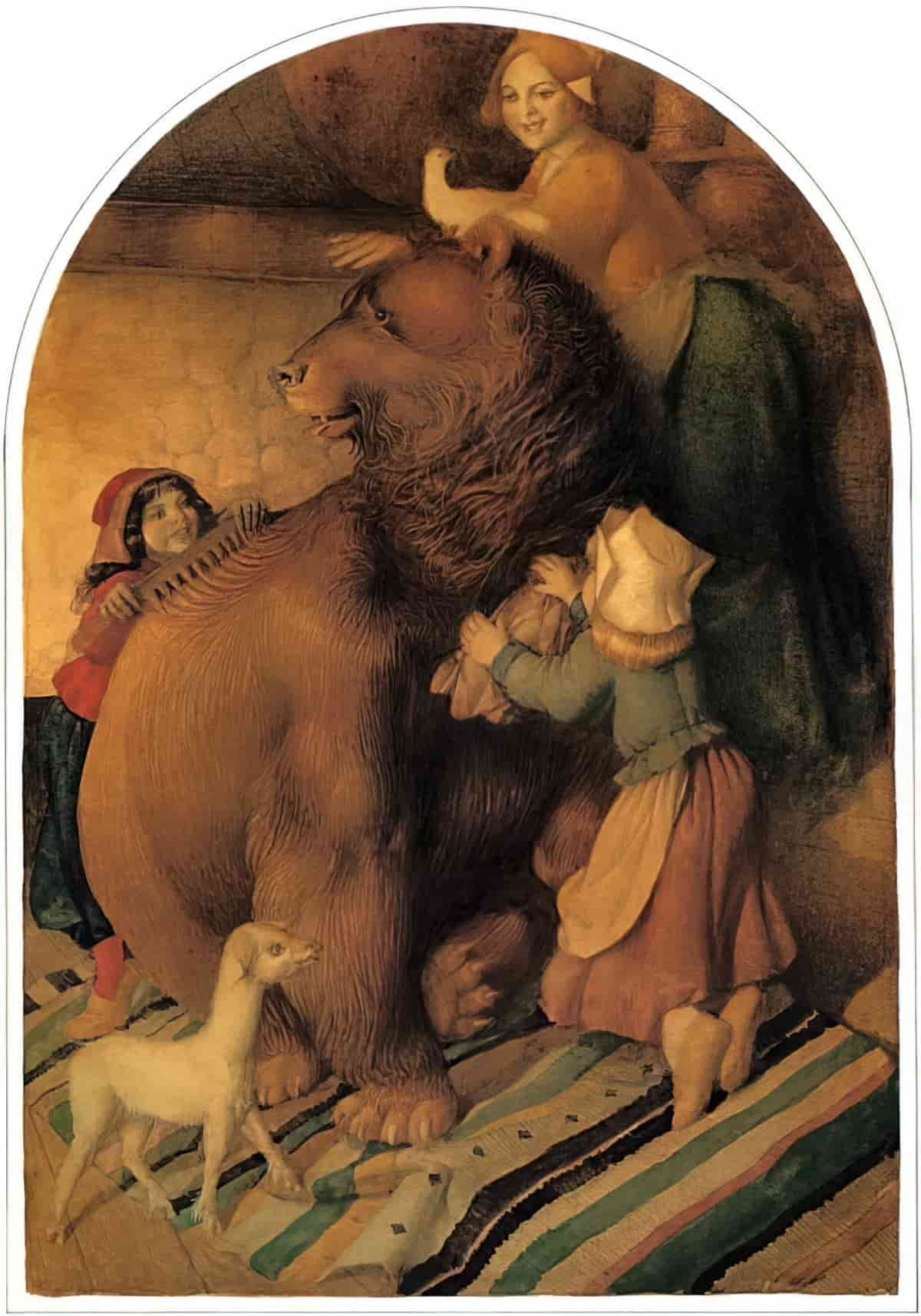

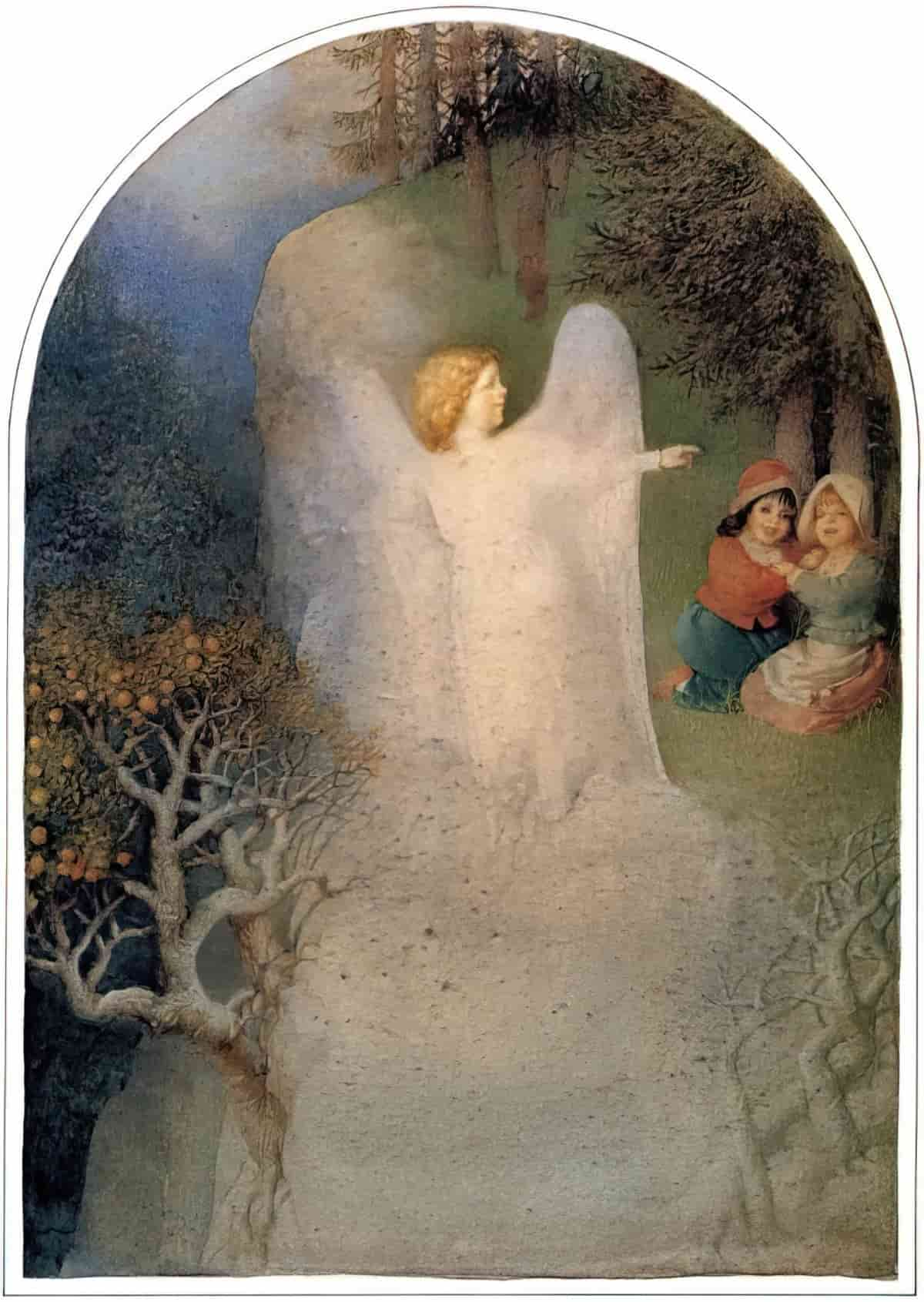

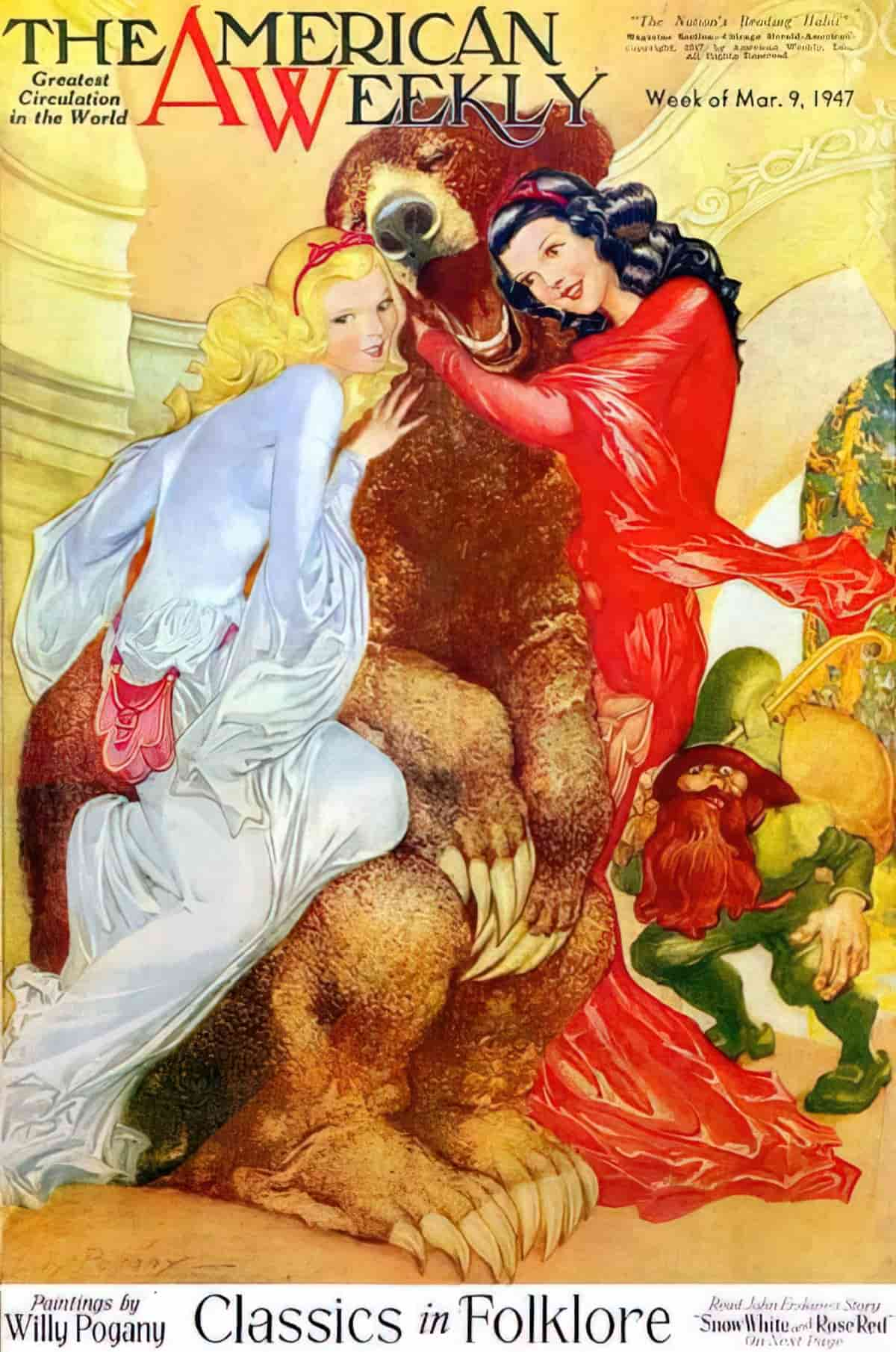

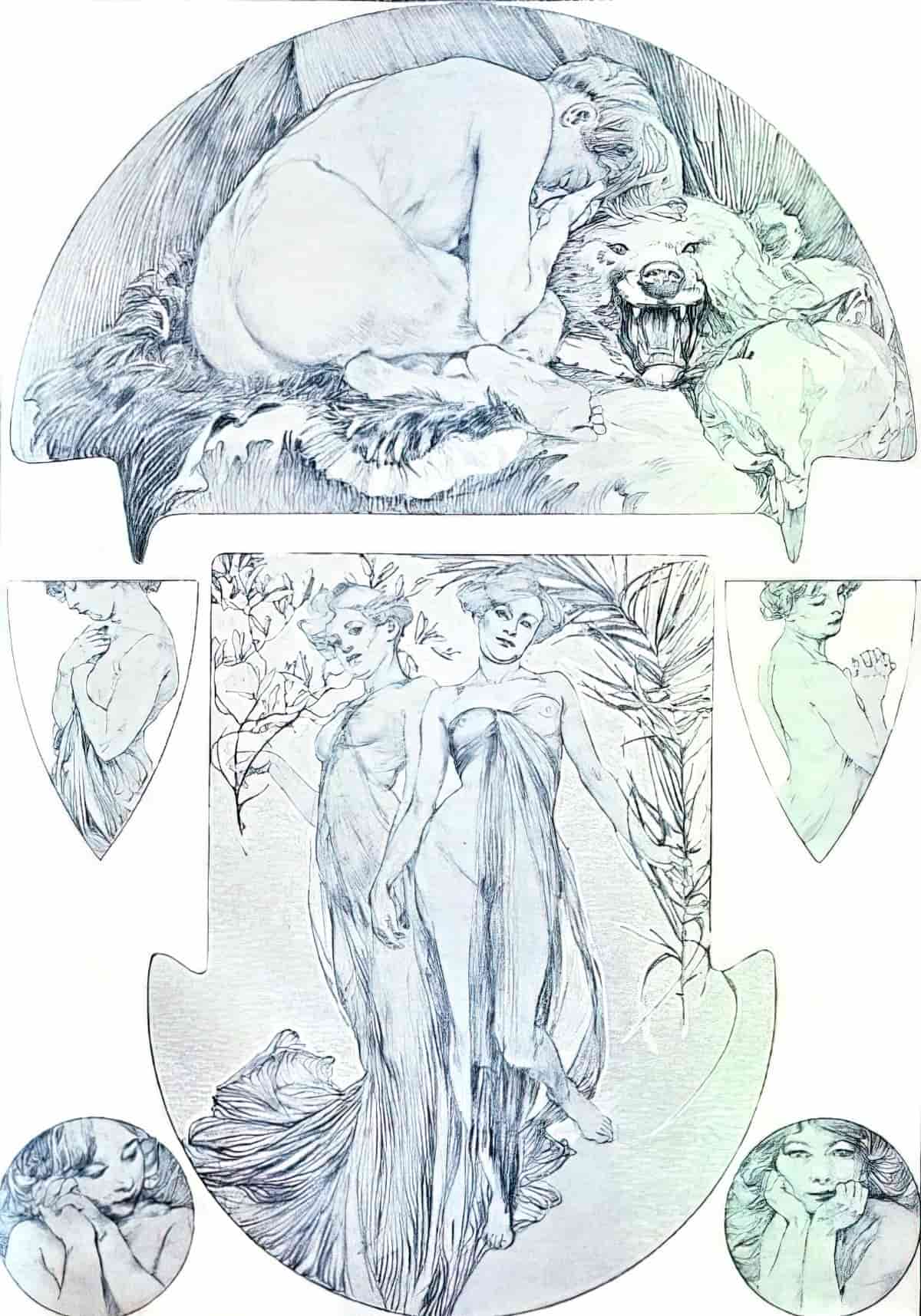

Scenes of pretty young women taking care of hirsuite beasts in front of the hearth is a common scene across fairytale. Below, an illustration for a Scandinavian tale. And because it is Scandinavian, the beast is translated into English as ‘troll’.

BIG STRUGGLE

Making use of the Rule of Three, the girls keep rescuing the angry little dwarf. The reason they do this has been proposed in the first section of the story: They help someone out of trouble because they are Good. They are basically Goodness Automatons. These girls have never considered ethical dilemmas such as The Trolley Problem, in which we sometimes help more people by sacrificing one.

Eventually the bear turns up to save the girls from the dwarf’s wrath. The dwarf tries to convince the bear to eat the girls instead.

ANAGNORISIS

“I am a king’s son, who was enchanted by the wicked dwarf lying over there. He stole my treasure, and compelled me to roam the woods transformed into a big bear until his death should set me free. Therefore he has only received a well-deserved punishment.”

SPELLS BROKEN AT DEATH

The idea that a spell can be broken once your oppressor is dead can be found across various superstitious cultures. Most disturbing is that of the houngans in Haiti, origin of zombie mythology.

A houngan is a type of voodoo priest. In this community, if you want to take revenge on someone, you pay this houngan to give your victim a deadly neurotoxin out of a pufferfish. This toxin convincingly simulates death. The victim’s family thinks they’re dead and buries them. However, the houngan digs them back up and revives them, sort of. This newly minted ‘zombie’ is kept ‘in thrall’ and used as a slave. The zombie is not properly fed — they must be kept in a malnourished state. In fact, feeding zombies salt or meat may be enough to rouse them from their stupor. At this point they’ll either kill their master, kill themselves or go running back to their grave.

When the houngan dies, the zombie person is meant to be free. But sometimes that just means jumping to their death.

Although the supernatural parts of that story are not real, the zombie status of certain ostracised people is completely real. That’s what disturbs me the most. Imagine visiting a community in which someone is ignored, because everyone believes they’re the walking dead.

The living person who thinks they are really dead is utilised in the comic book series House of Whispers, written by Nalo Hopkinson (a Jamaican-born Canadian author). Jamaica is very close to Haiti, and Hopkinson has clearly made use of ancestral belief in her original additions to the Sandman universe.

NEW SITUATION

There is only one happy ending for girls in fairy tales — marriage to royalty. The prince regains his rightful treasure. (I doubt it was rightful.) They end up with even more treasure than before. Instead of trying to return it to its owners, they keep it, because they are royalty.

Snow White marries the prince and Rose Red marries his brother.

EXTRAPOLATION

The mother moves out of the cottage and presumably into the palace with her daughters.

RESONANCE

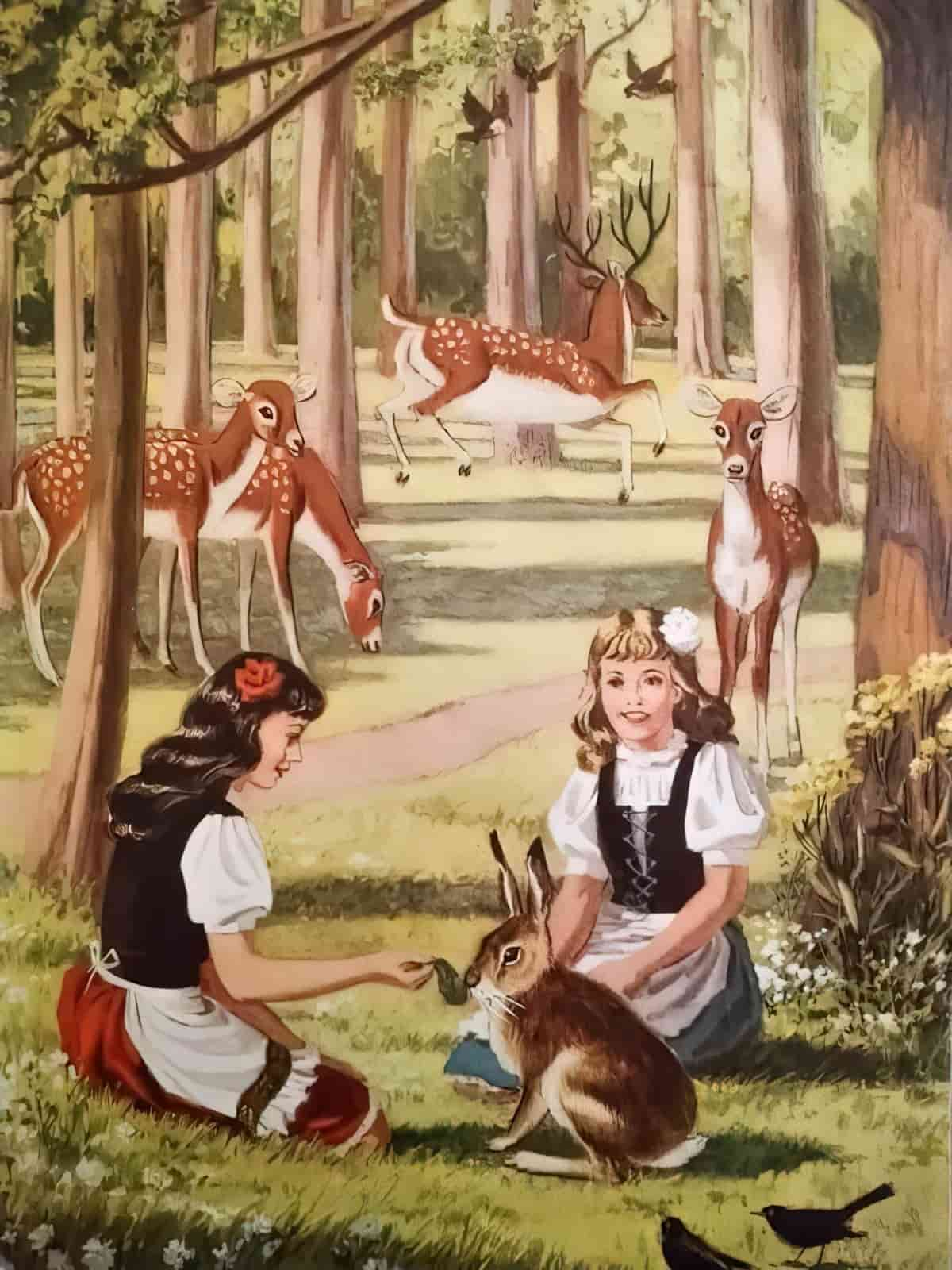

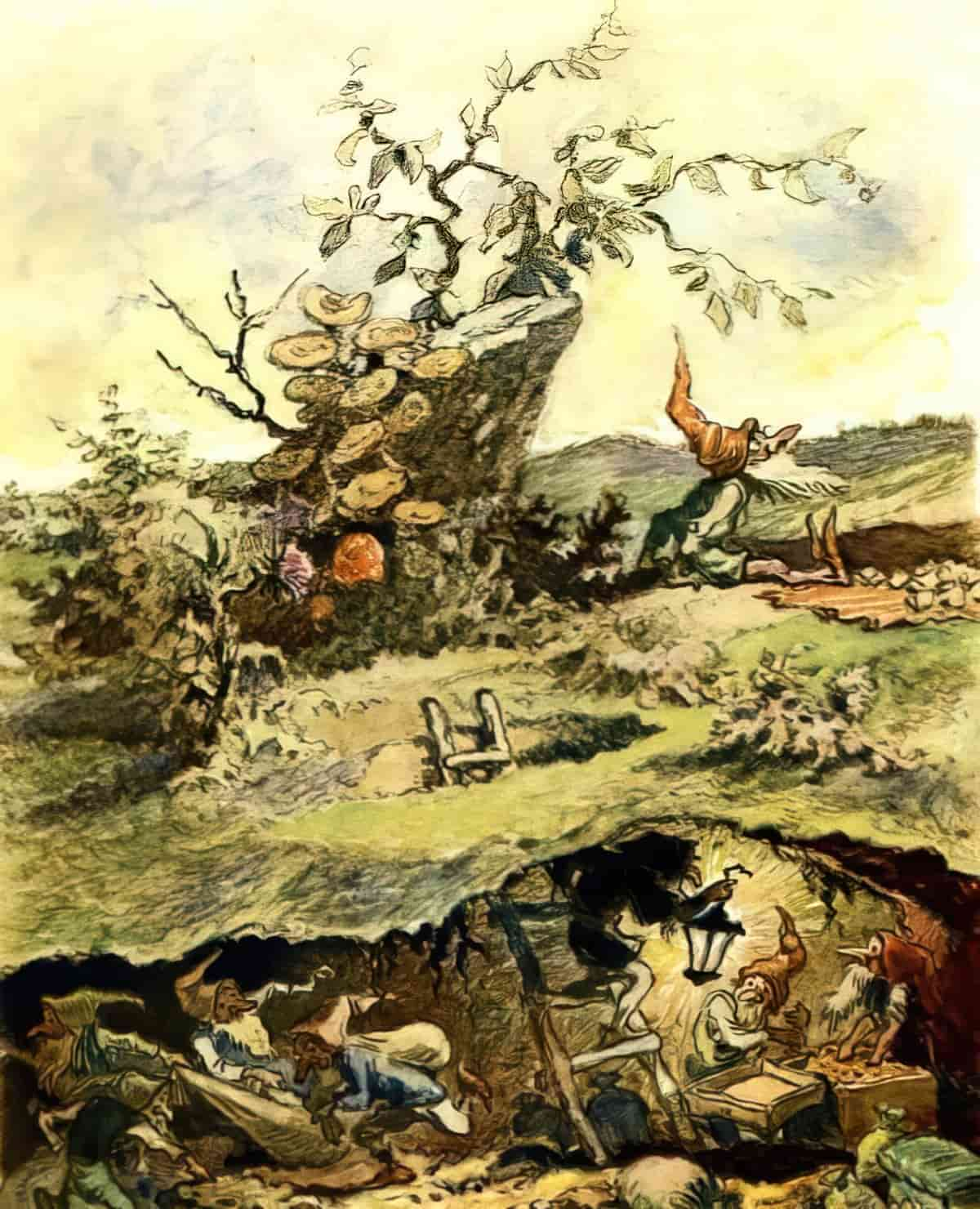

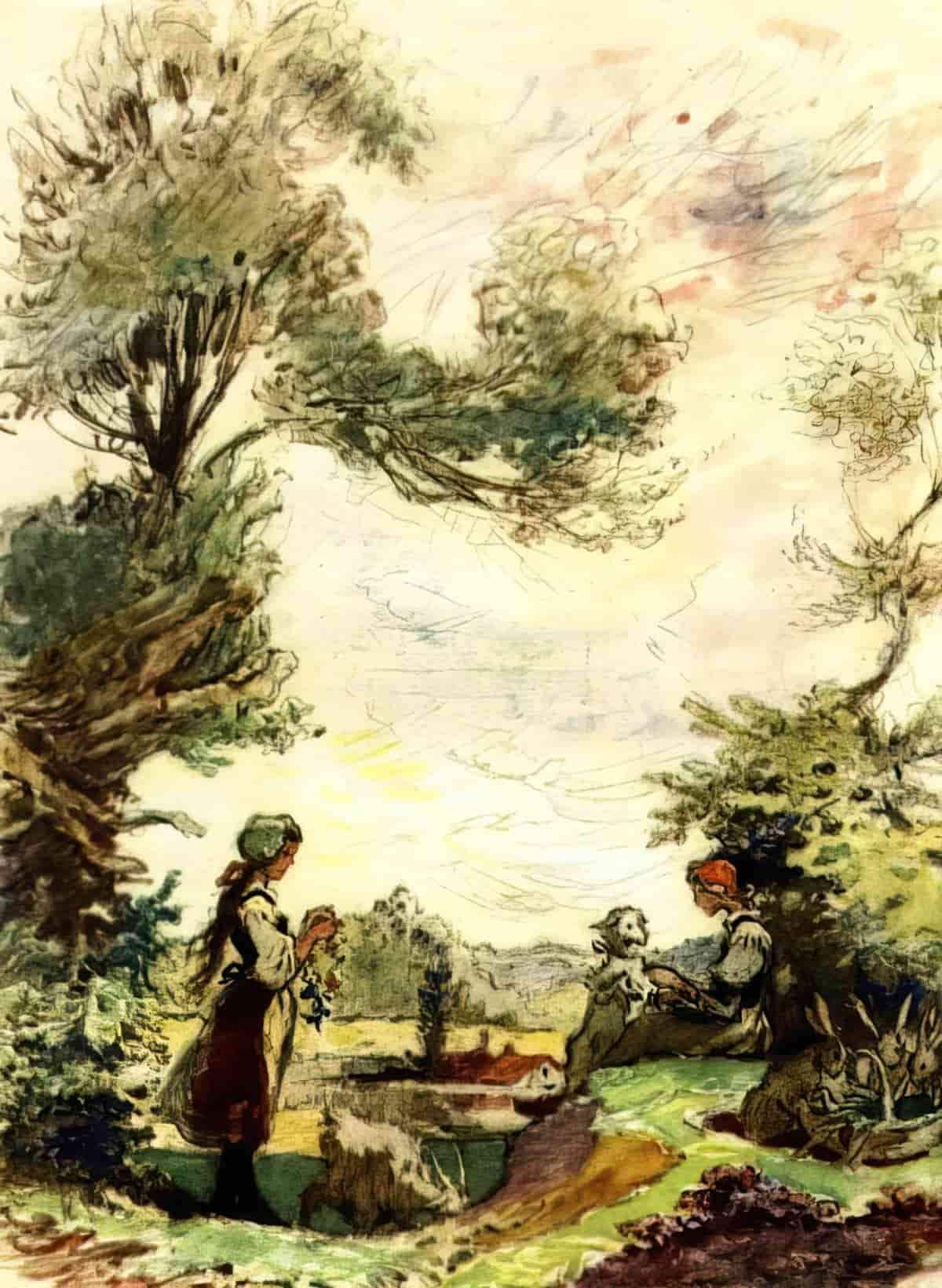

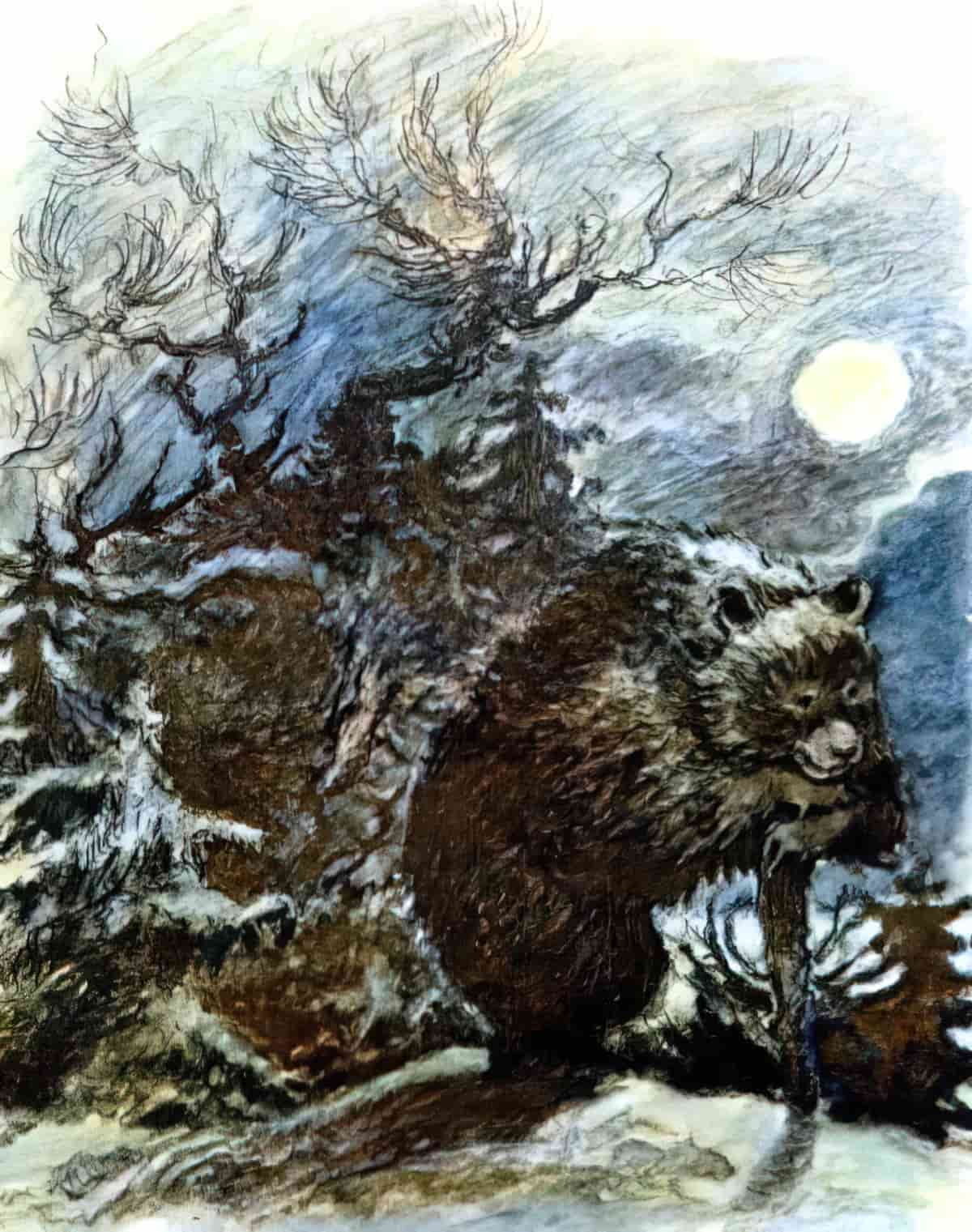

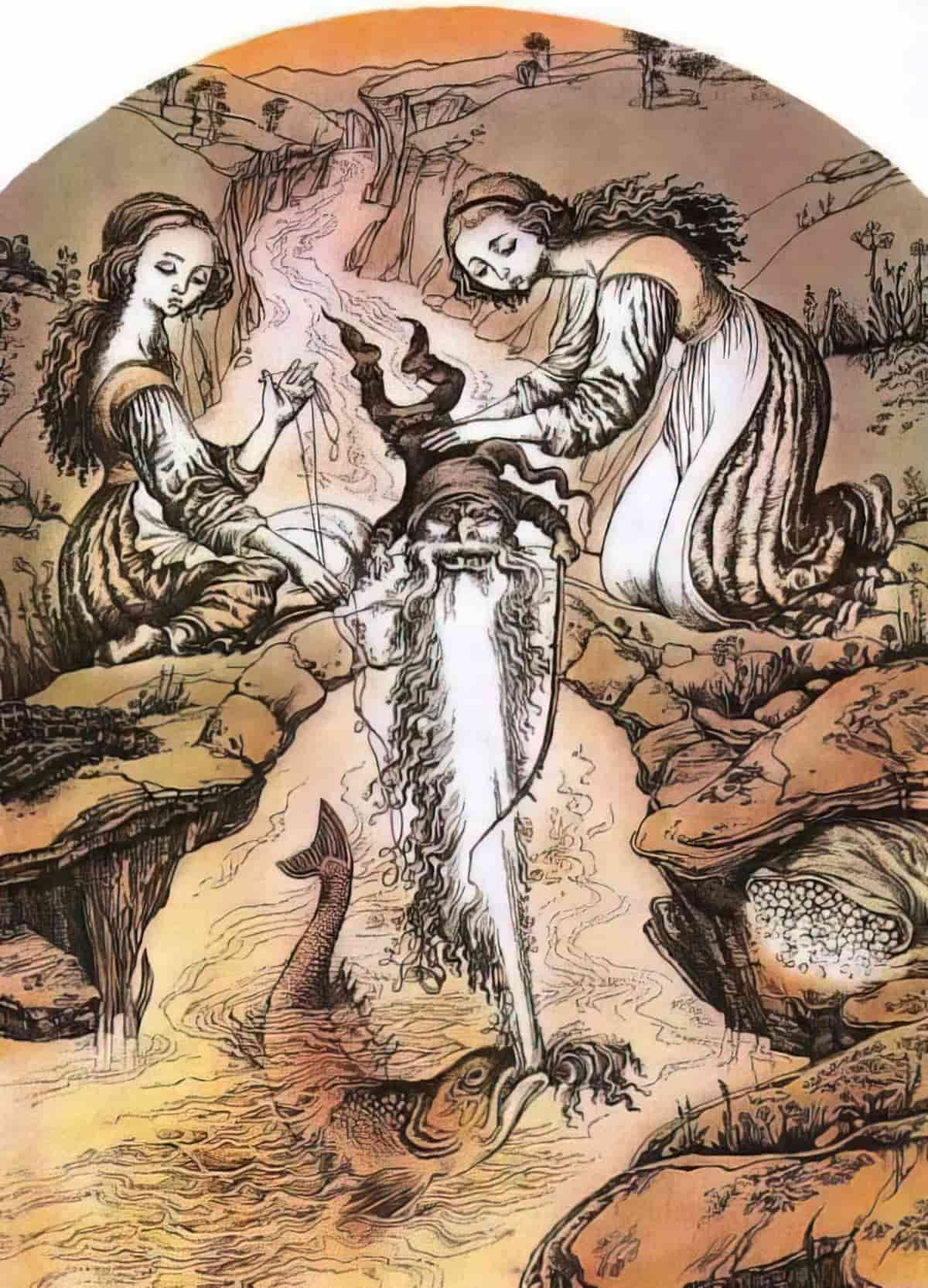

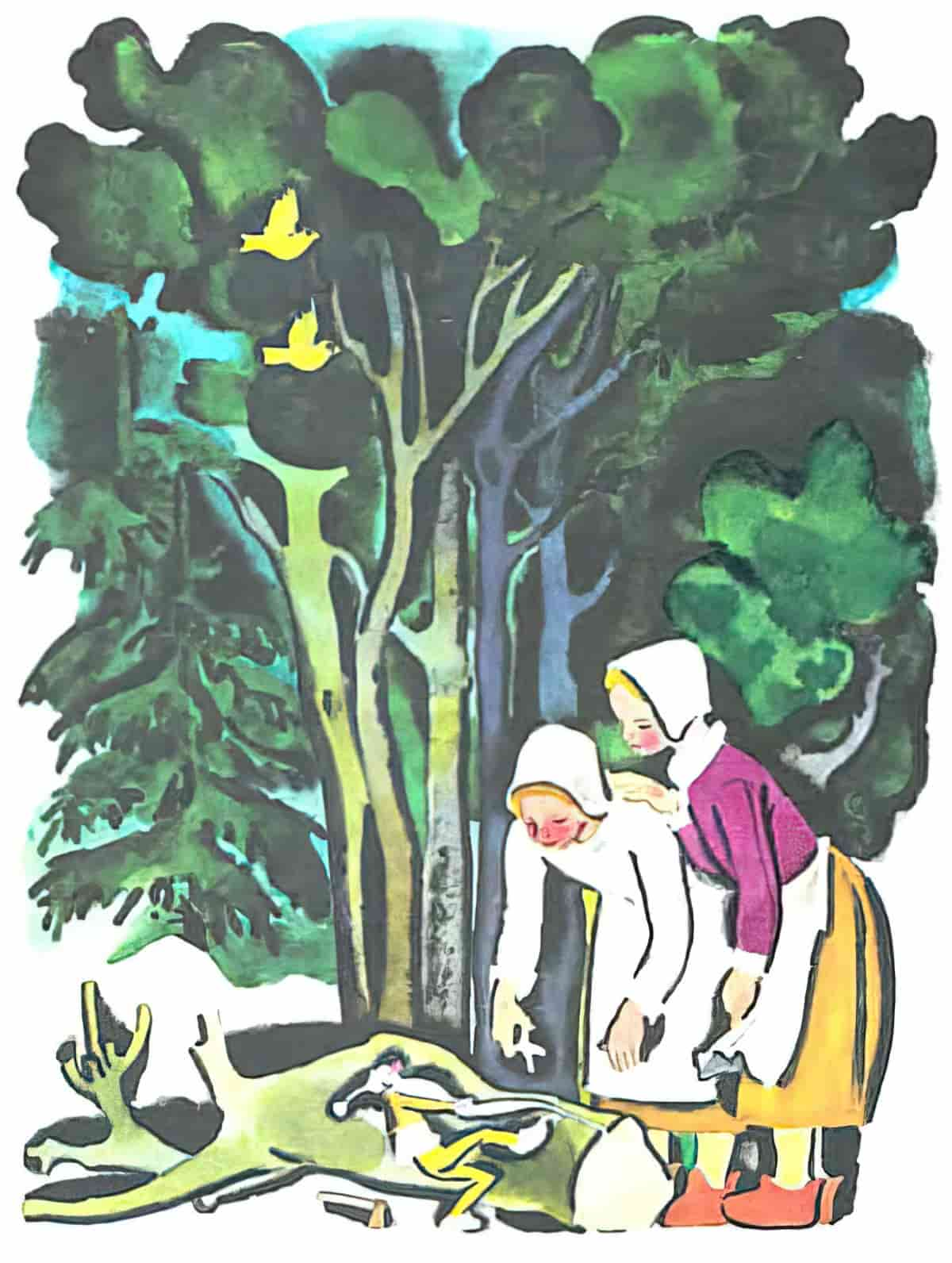

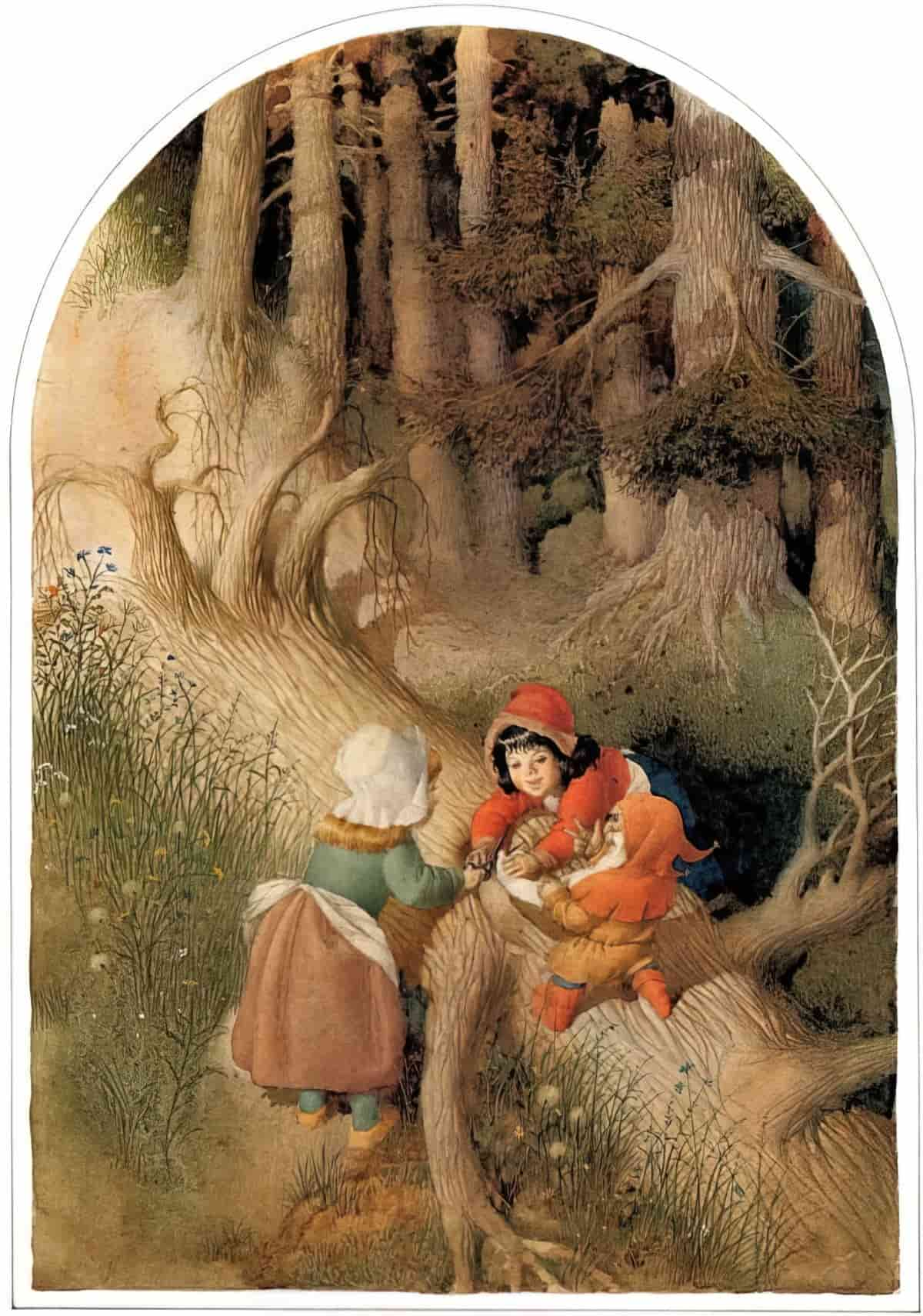

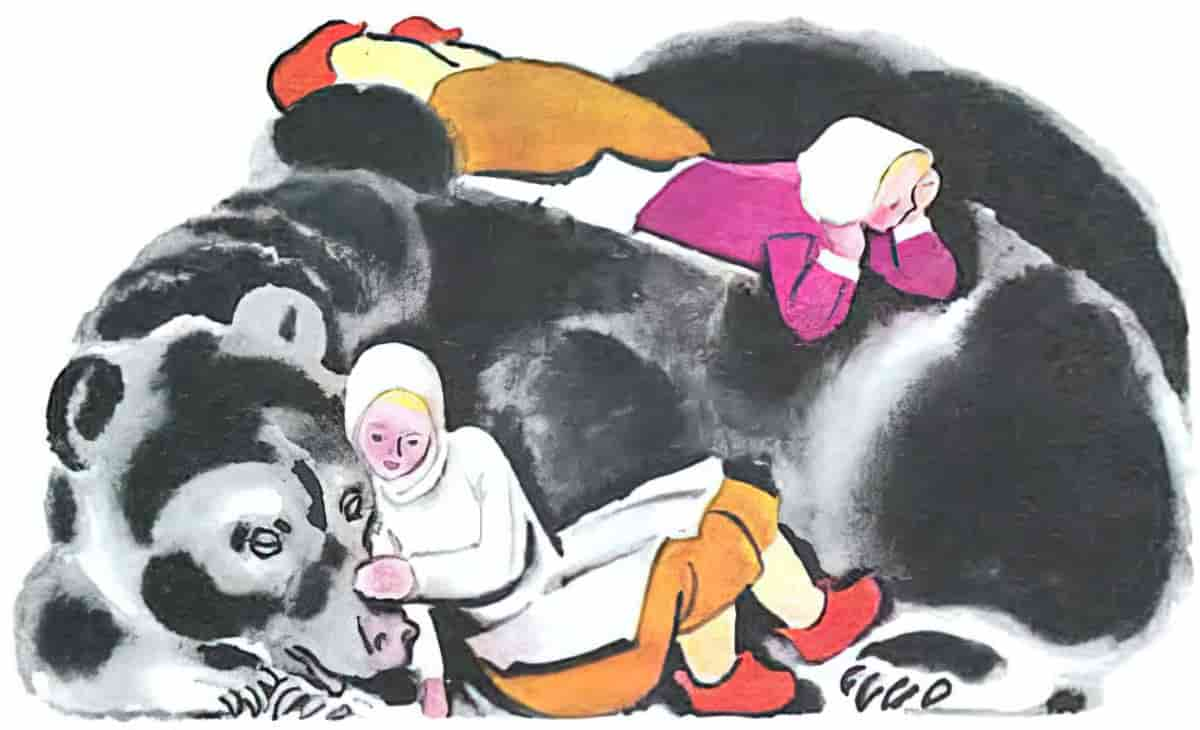

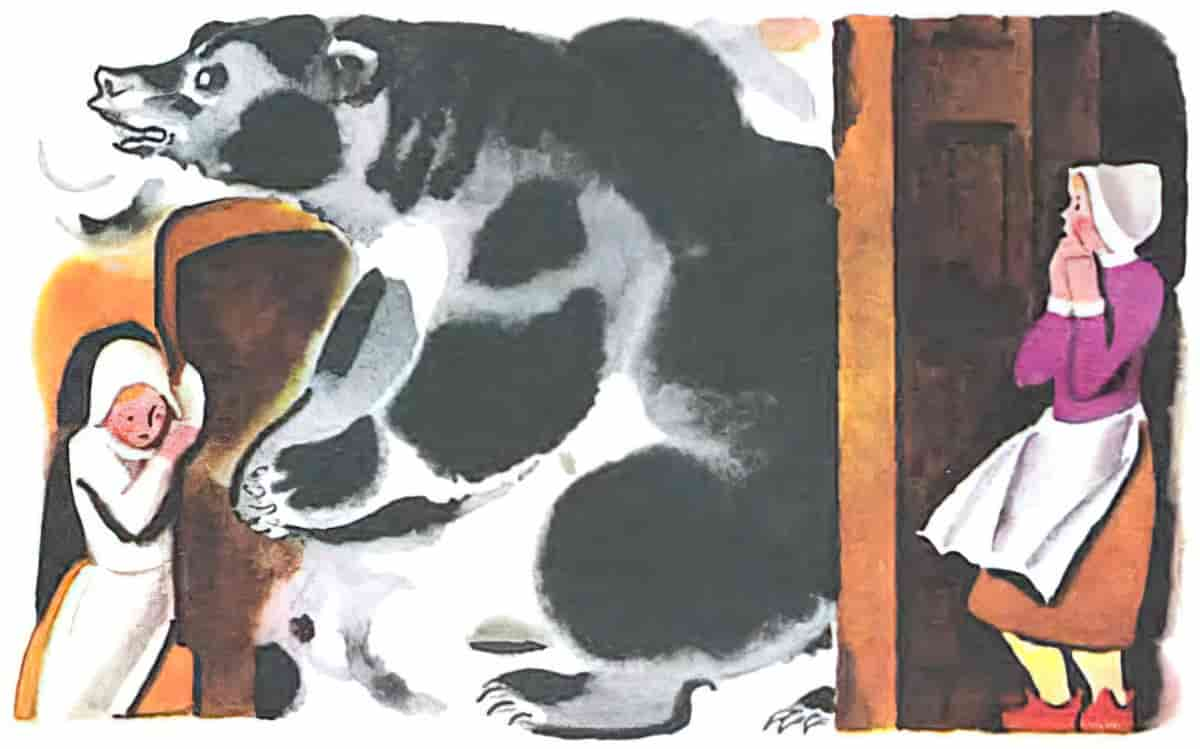

Snow White and Rose Red resonates across cultures. Here are illustrations by N. Zeitlin for the Russian version, “Belyanochka and Rosochka”.

THE FLOWERS

OLD WOMAN KNITTING

SNOW WHITE AND ROSE RED RUNNING

THE FISH

THE DWARF AND THE TREASURE

SNOW WHITE AND ROSE RED IN NATURE

THE COTTAGE

THE HANDSOME PRINCE

THE FORMIDABLE BEAR

TAKEN BY THE BIRD OF PREY

THE STUCK BEARD

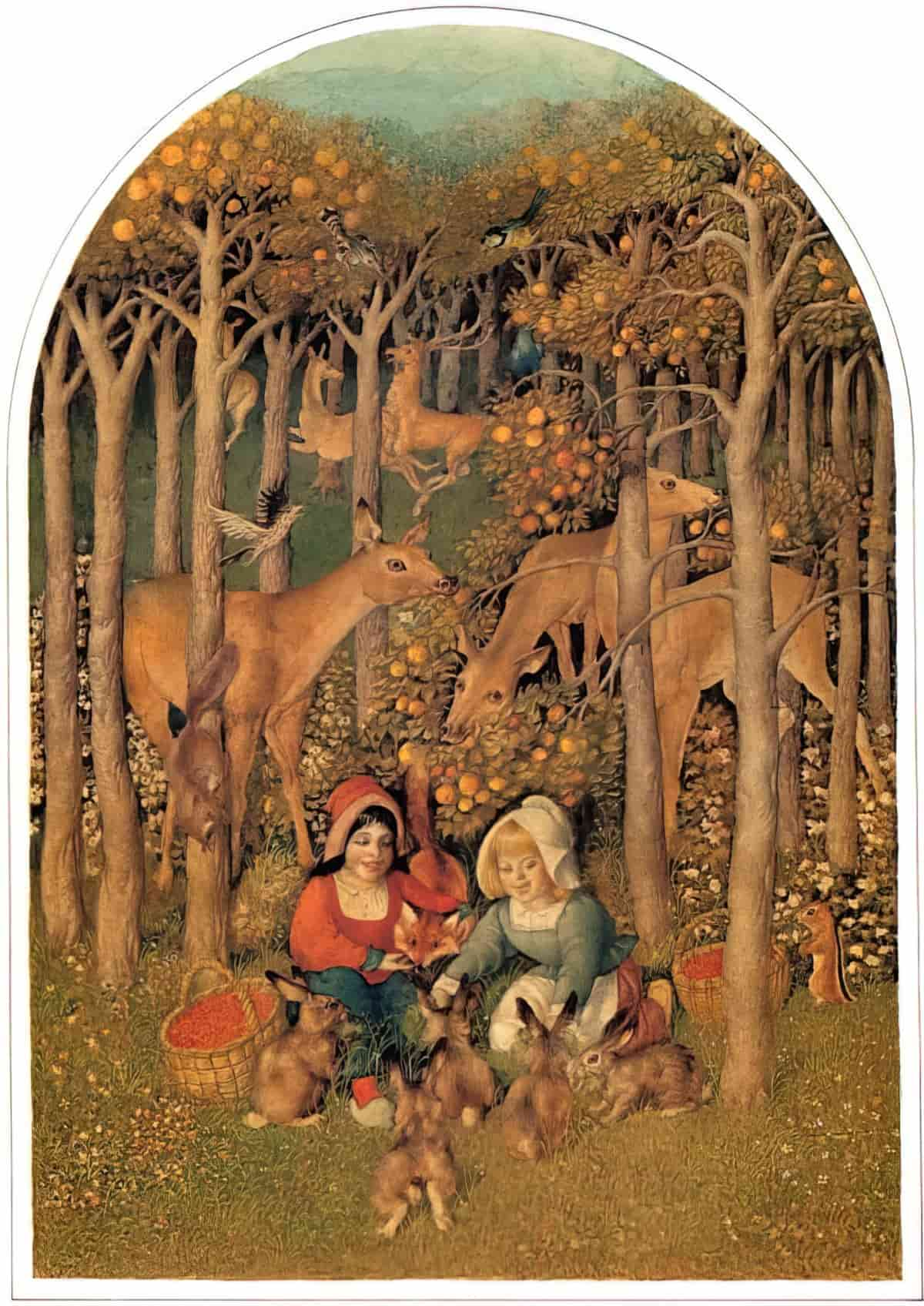

SNOW WHITE AND ROSE RED PLAY WITH THE BEAR

THE BEAR AND THE GIRLS IN FRONT OF THE FIRE

THE BEAR AT THE DOOR

ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE ENDING

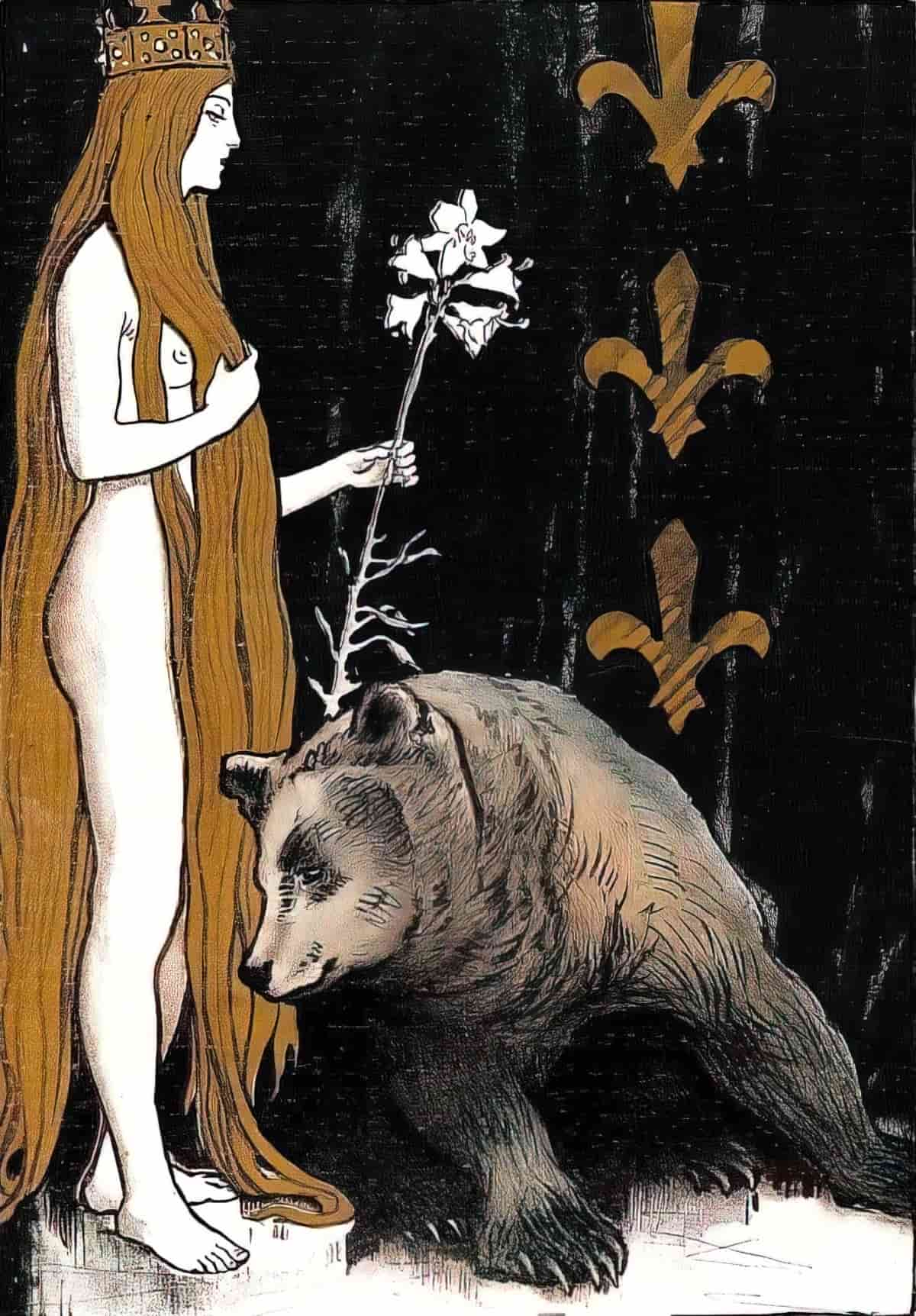

BEARS AND FEMININITY

In some old European towns, houses had altars to the goddess in each room. She often stands flanked by animals, usually male animals. The corpulent goddess of the late Palaeolithic is transformed in horticultural society to a slimmer figure flanked by domesticated rather than wild animals. The animals most frequently depicted are dogs, the bull, and the he-goat. The goddess is also frequently associated with the bear. Gimbutas theorizes that the maternal devotion of the bear made a deep impression on Old European horticulturalists, so that she was adopted as a symbol of motherhood; in any case, many figurines of mother and child show the child with the head of a bear. The vegetation goddess was associated with pigs.

The meanings of these animal associations are not always clear. Pigs are fast-growing and associated with grain; dogs bay at the moon, the cosmic body identified with the goddess and with regeneration, waxing and waning; and dogs constituted the major sacrificial animal. Bull horns resemble the lunar crescent.

Marilyn French, Beyond Power: On Women, Men & Morals p23

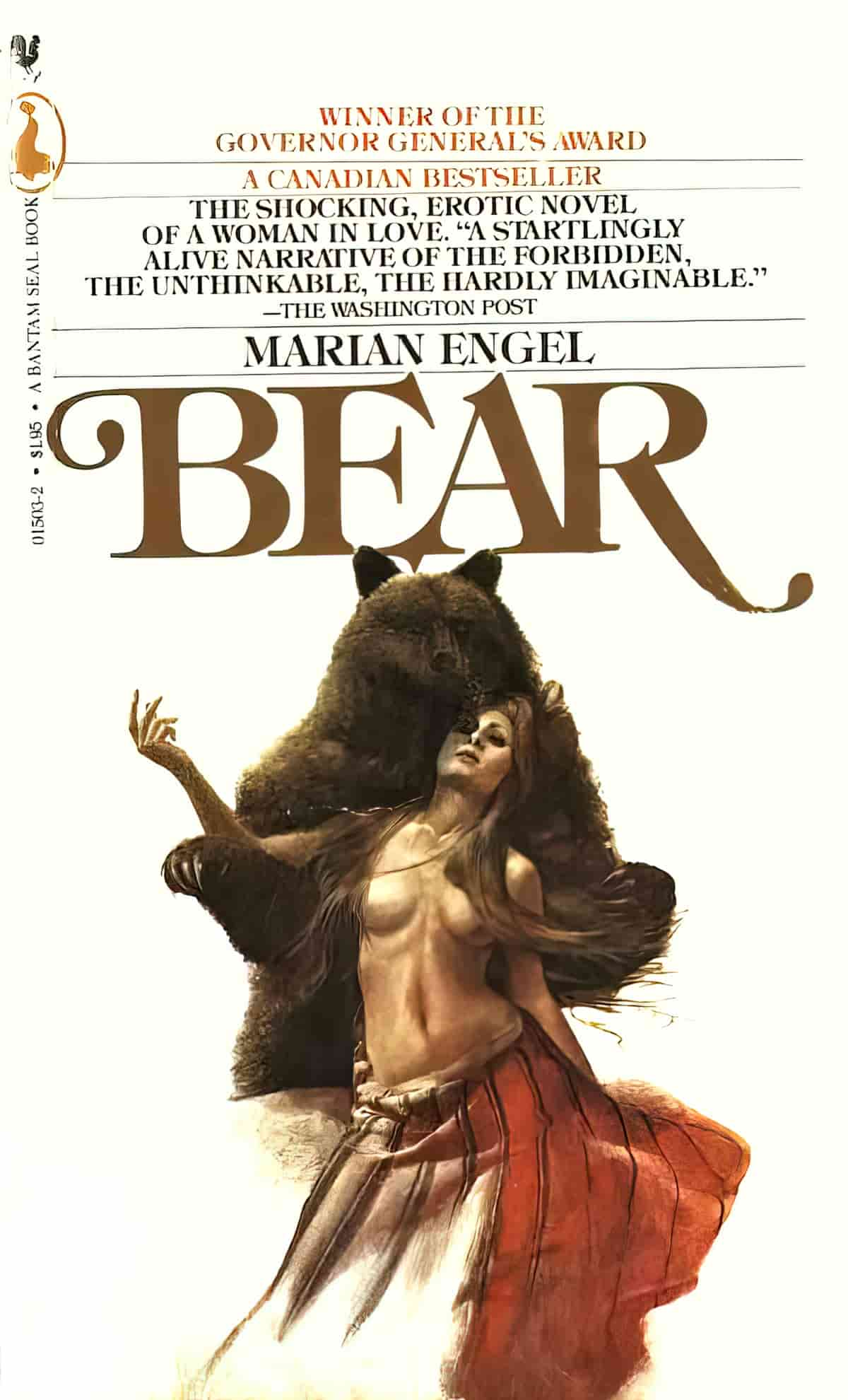

BEARS, YOUNG WOMEN AND EROTICISM

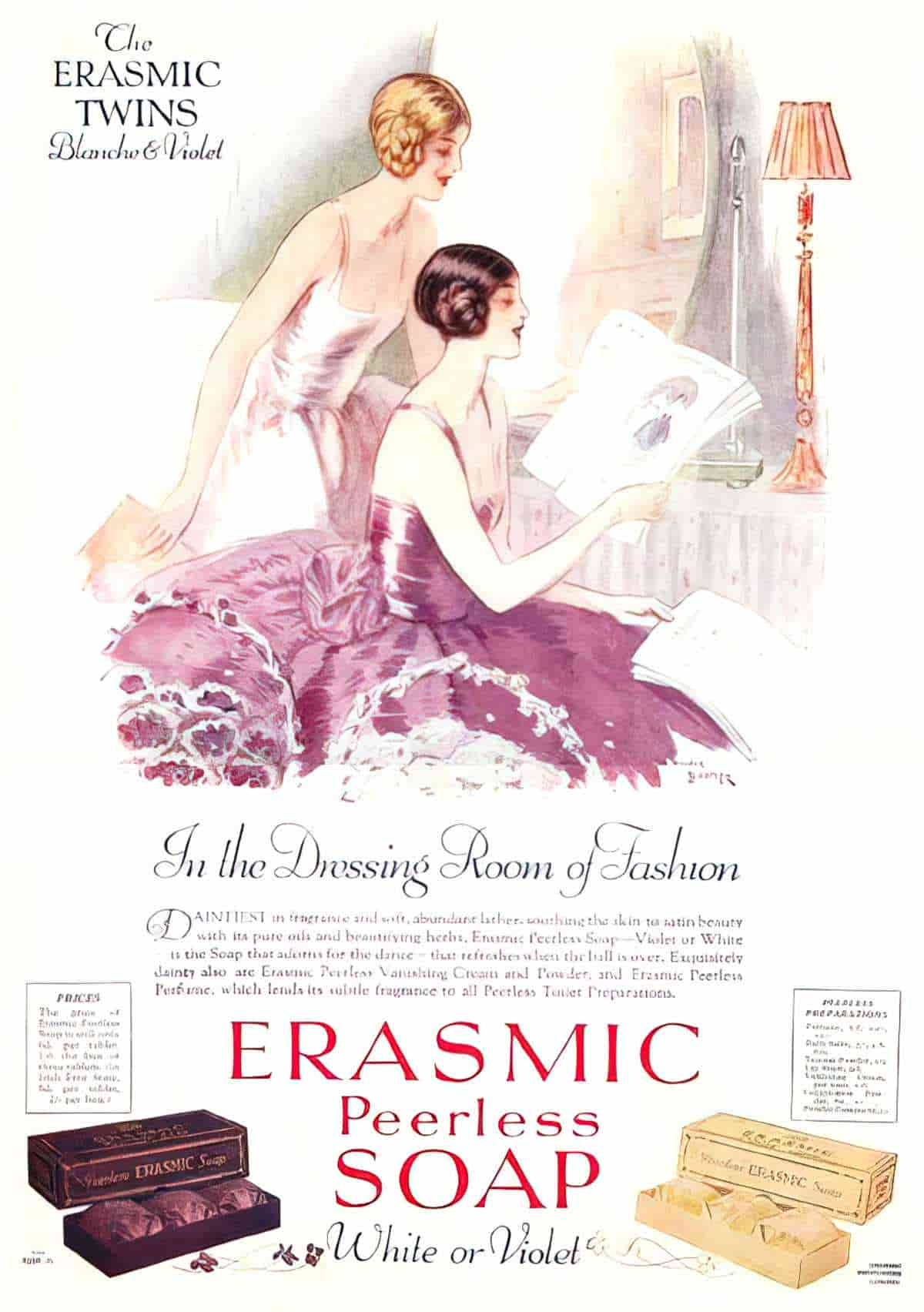

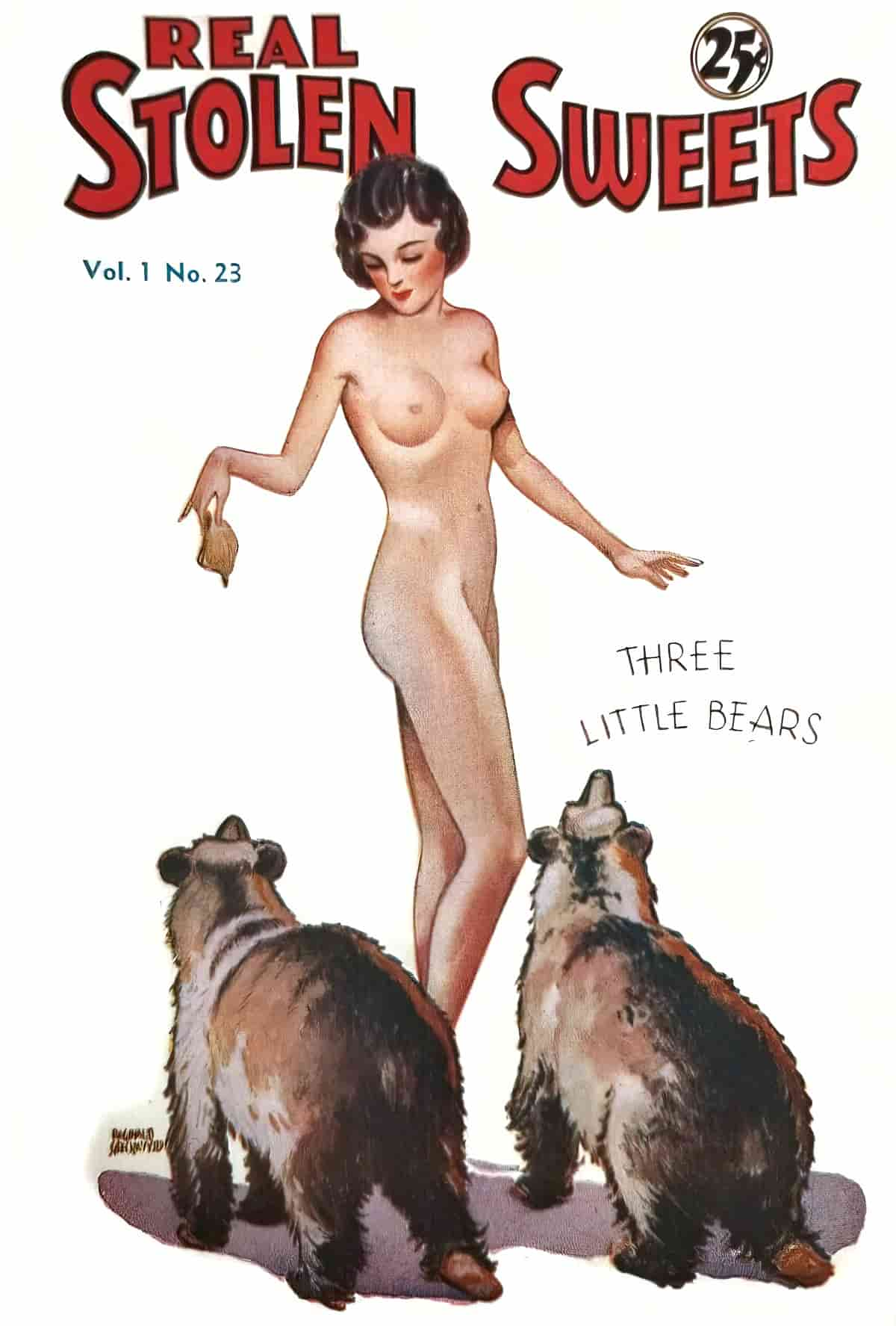

Probably because of the Disney film, Snow White from the story with the seven dwarves is the more famous Snow White. This remains a tale for those who read fairytale collections. I think “Snow White and Rose Red” would’ve been much better known 100 years ago, which is why a soap advertisement like below worked for an earlier audience.

But the trope of the female duo (twins, sisters, friends, enemies), each with a different colour hair, remains a staple. TV Tropes call one iteration the Betty and Veronica trope. On film, TV and in illustrated books, it’s really handy to give two girls different coloured hair — the audience won’t get them mixed up. This is why the actress who plays Paris on Gilmore girls was asked to colour her naturally brown hair to blonde, to make her visually distinct from Rory Gilmore.

More widely, we seem to have a bit of a thing for dangerous bears and pretty young virgins rubbed up together. I theorise this is because the bear symbolises brute masculinity, and the virginal young woman is peak femininity, and we traditionally like to see those particular outworkings in the same room.

In this case, I don’t think for a second that a veiled sexual reading of this fairy tale is the modern one; I suspect the inverse is true — bowdlerised versions of Snow White and Rose Red have tried (with only moderate success) to erase the sexual nature of a bear coming to visit maidens in their home. However, contemporary writers such as Margo Lanagan did bring the full force of bestiality back into it, where it actually always was.

The imaginative connection between women and bears goes way back into antiquity. The Roman/Greek goddess Diana/Artemis’s spirit animal was the bear. This character is goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, the Moon, and chastity.

Then there’s Callisto, Artio, Ildiko and Mielikki. All coded femme, all associated with bears.

Header illustration: Richard Doyle — Snow White and Rose Red 1877