Six Dinner Sid is a 1993 picture book written and illustrated by Inga Moore.

The plot of the cat who goes from house to house pretending to be anyone’s will be familiar to anyone who’s ever known a cat. There’s an episode of cult hit This Country (“The Vicar’s Son”) in which Kerry Mucklowe eats her mum’s dinners, then sort of falls opportunistically into a scheme whereby she cadges dinner off an elderly lady living in the same village. The audience soon realises that Kerry is behaving exactly like a house cat.

Six Dinner Sid is a picture book cat who does the same thing. In these stories about opportunistic tricksters, there’s a storytelling rule which I have not yet seen broken: At the climax, their scheming ways are exposed for all to see. The mask comes off. Two types of stories rely heavily on the mask: thrillers and comedies. This is more comedy than thriller. For a thriller cat picture book which also uses a mask, see Slinky Malinki by Lynley Dodd.

SETTING OF SIX DINNER SID

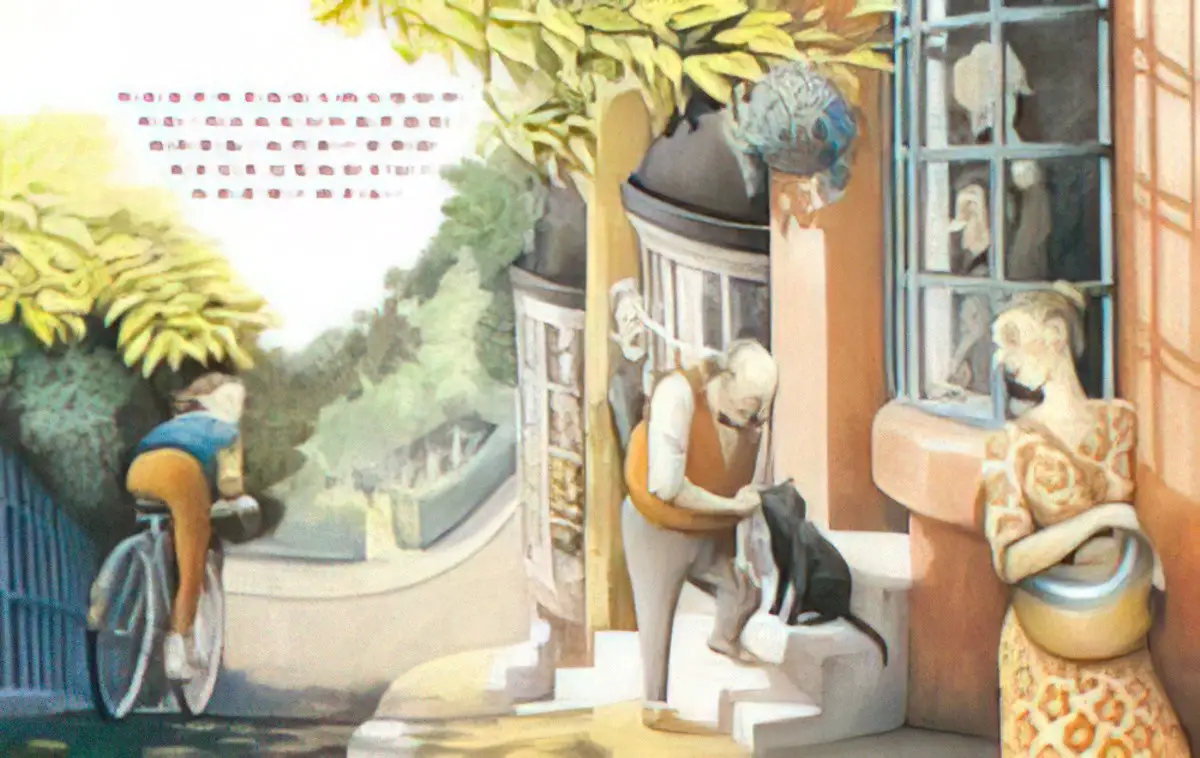

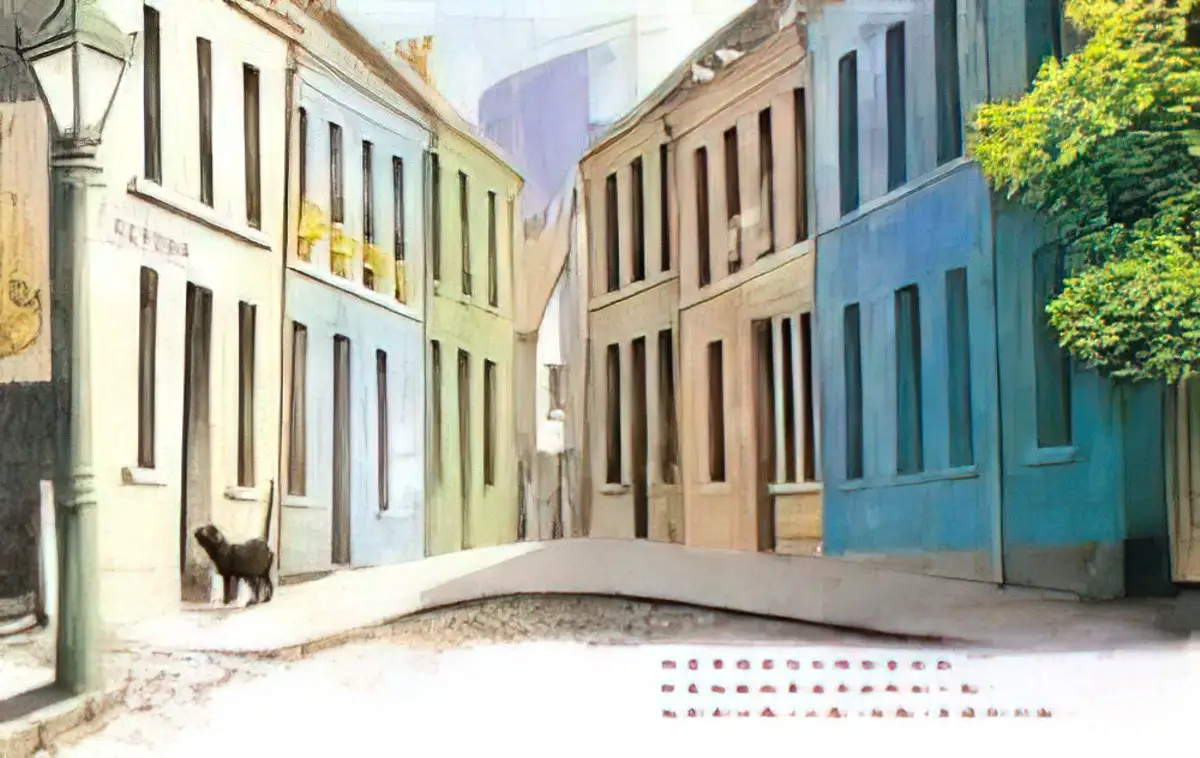

Inga Moore has beautifully depicted two British streets. One street contrasts with the other, in a didactic kind of way to be fair — in Aristotle Street the neighbours don’t talk to each other, whereas in Pythagoras Place, one street over, they do.

On the naming of the streets, one Goodreads reviewer said the following:

A sly commentary on the atomisation and breakdown of traditional social cohesion in urban communities that possibly also contrasts Aristotle and Pythagoras as philosophical and social role models in the form of a children’s picture book.

Geographically proximal streets tend to have a sameness about them, so in order to contrast these streets so that readers don’t get them mixed up, Moore depicts them quite differently. (I notice the people living in the richer looking houses are meaner.)

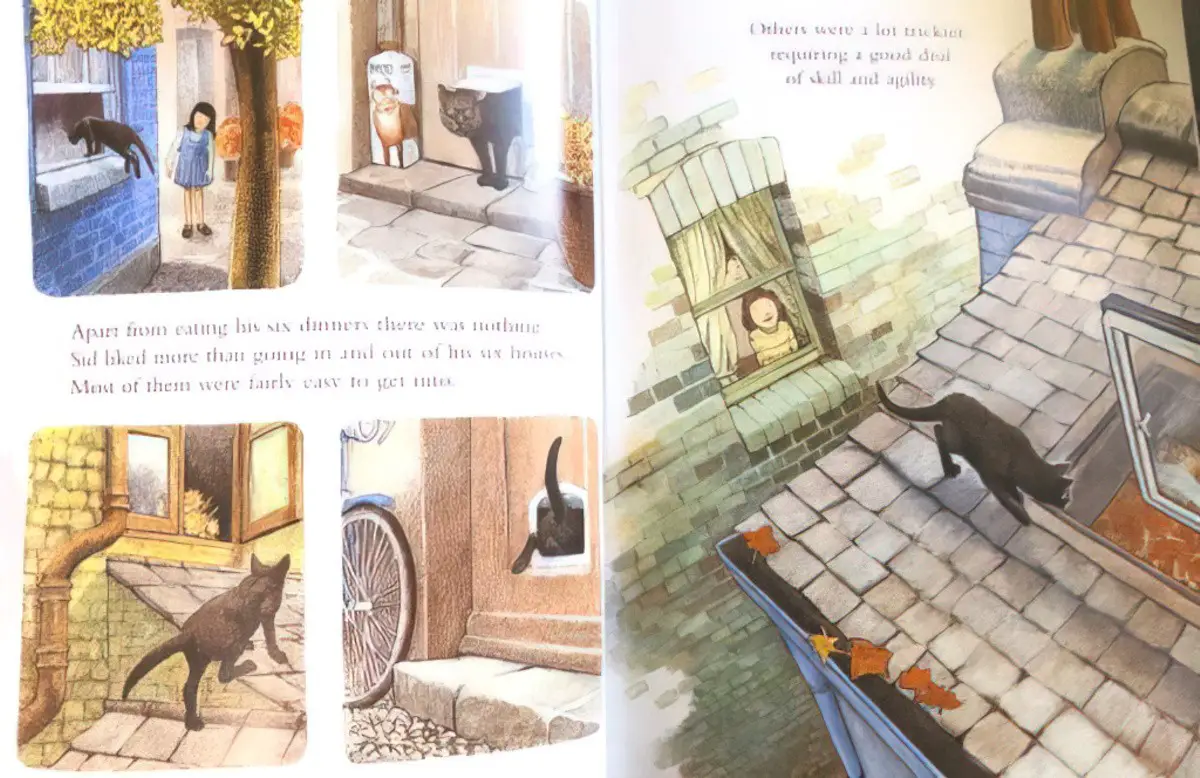

Some picture books are illustrated in a way which emulates a stage, where a member of the audience takes a seat and sees each picture from basically the same angle. Folk art picture books are good examples of this, like Rosie’s Walk. Other picture books are more cinematic, meaning there are cameras, affixed to drones, which can go anywhere at all. Six Dinner Sid is a cinematic style of picture book. The high angle shot of the roof is a good example of an angle unavailable to theatre audiences. The recto side of this spread is actually a shot unavailable to film makers, too. How often is an audience able to see a view of a cat getting in through a skylight and two children watching on from across the street… in a single shot? Hardly ever. This is the beauty and huge advantage of illustration, which is not just cinematic but ultra-cinematic. The illustrator can create any shot they want.

STORY STRUCTURE OF SIX DINNER SID

PARATEXT

Unbeknownst to each of his owners, Sid the cat lives with six different people on the same street. By doing so, he’s able to get six different dinners every night! He also answers to six names, sleeps in six beds, and maintains six different personalities.

All is perfect for Sid – until the day he catches a dreadful cough. Then it is off to the vet not once, but six times! Inga Moore’s humorous illustrations capture Sid’s sly nature.

SHORTCOMING

Sid is a slightly anthropomorphised cat, but not by very much. He’s about as cat as Judith Kerr’s Mog. Sid retains most of his catness, which means he is disloyal, opportunistic, but doesn’t ‘scheme’, as such. Since Sid doesn’t have a plan, he will be easily found out.

Like any contemporary picture book cat, Sid is a grandchild of one of T.S. Eliot’s cats, which have become archetypes. In Old Possum’s Book Of Practical Cats, cats are basically sorted into ‘houses’ or personality types. Slinky Malinki is a mystery cat, for instance.

In the second image of Sid, Moore has painted him licking his backside nonchalantly, which says everything you need to know about Sid.

However, he is required to be a different cat depending on the house. Slightly older children will appreciate this because at school different teachers require different things. Younger children with blended houses living in separate houses will also get it — the idea that different situations and people require different versions of yourself.

Sid is in one of the houses named ‘Scaramouche’ (a name I recognise from Bohemian Rhapsody). The scaramouche is a stock clown character of the 16th-century commedia dell’arte (comic theatrical arts of Italian literature). He is also called Sally, Sooty and Schwartz. He is the ultimate shapeshifter, transcending sex, but coincidentally always garnering a name which begins with the letter ‘s’. This is clearly a storybook clue to the young reader: All of these cats are the same cat.

Each of Sid’s ‘fursonas’ equate to a different cat archetype as established by folklore, nailed down by T. S. Eliot.

DESIRE

Like most cats I’ve known, Sid in all of his/her forms is utterly driven by food. It’s amazing he is not more chunky. Moore keeps him slim so that she can emphasis his bloated belly after his six meals.

OPPONENT

The silo mentality of the inhabitants of Aristotle street is exploited by the eponymous cat to score six dinners every day – at some psychic cost as he must remember six distinct names and identities, but the illustrations show him becoming pleasingly plump at the end of the day so the stress of performing the different roles required of him does not seem too overwhelming but perhaps that stress does precipitate the cough that exposes the dangers of the Aristotelian approach to life and brings to an end one phase of Sid’s heroic life, dedicated to the pursuit of life, liberty and six dinners a day and the rejection of the bourgeois anthropocentrism of the Aristotelians.

Goodreads reviewer

(Silo mentality is a reluctance to share information with employees of different divisions in the same company, or in this case, street.)

PLAN

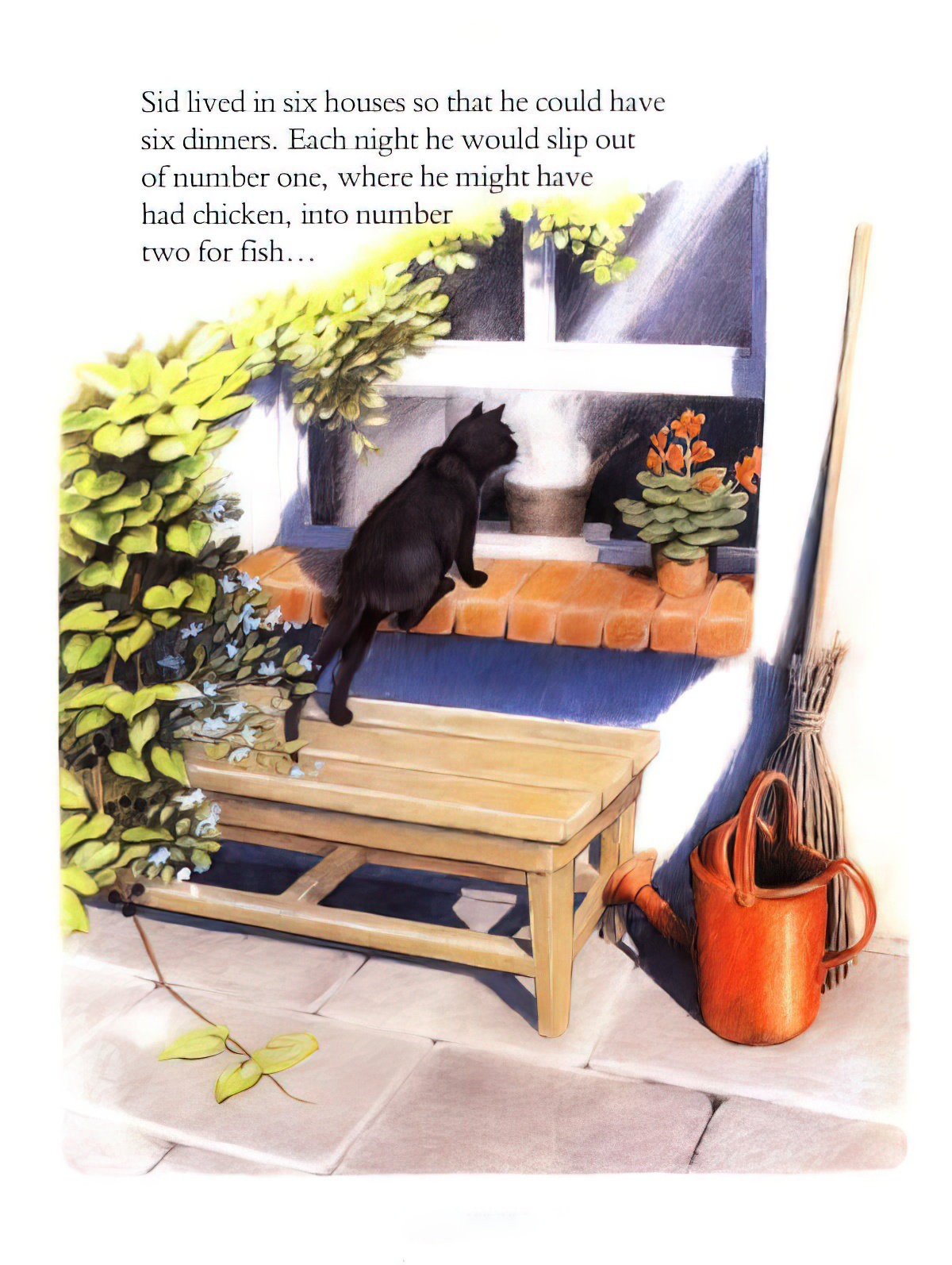

Moore shows Sid entering a house, but then speeds up the pacing by showing four scenes on a single page. This is an establishing shot. Notice the broom. Broomsticks and black cats are always reminiscent of witches, which adds just the faintest hint of supernatural possibility. However, this is not, in the end, a supernatural tale.

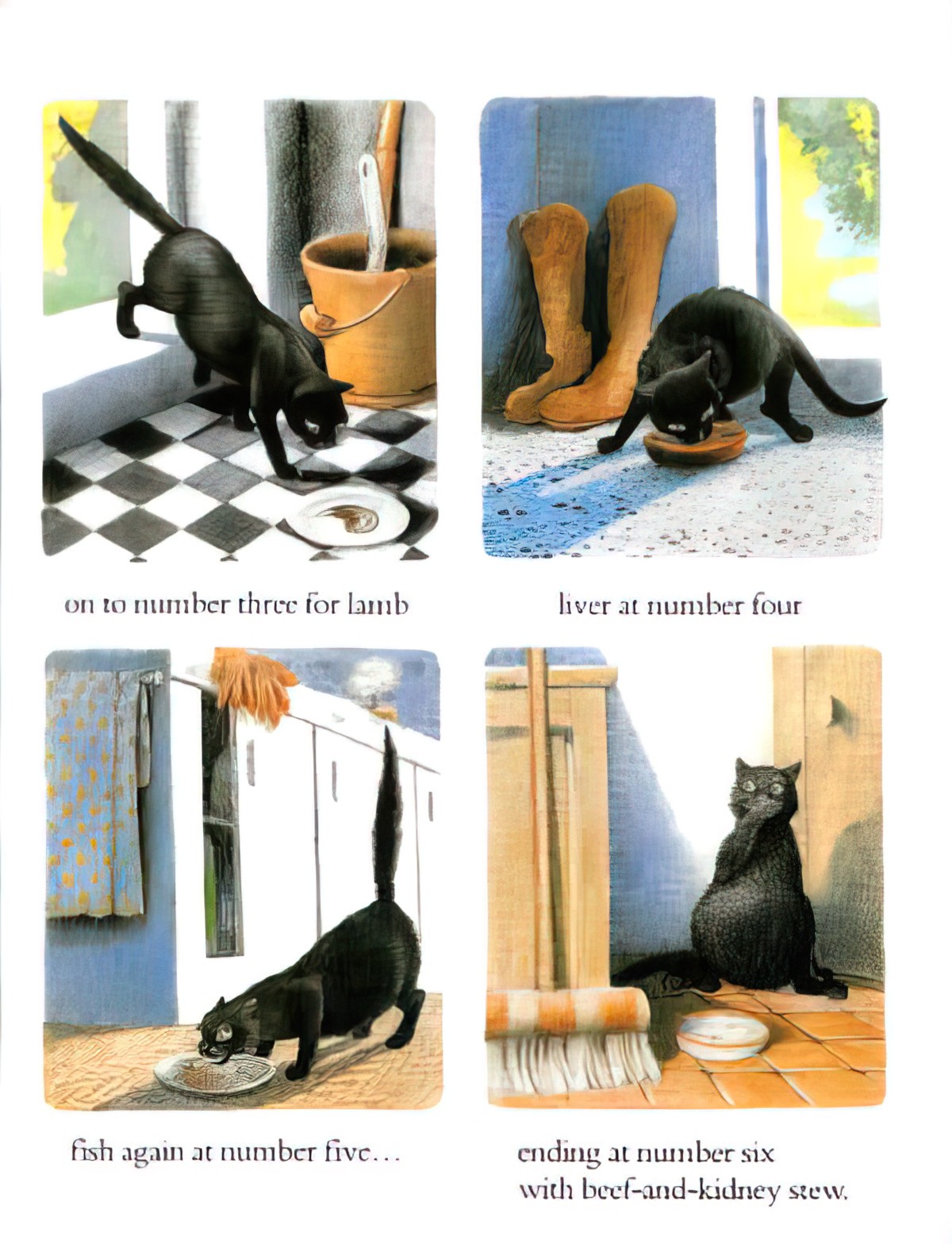

Food is important to children’s literature. Picture books regularly contain lists of food. The Very Hungry Caterpillar and The Tawny Scrawny Lion are some well-known examples which also link food with another kind of sequence — either numbers or days of the week. It’s interesting that Moore chose six and not seven, because I have almost been trained to expect food to be linked to the days of the week.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

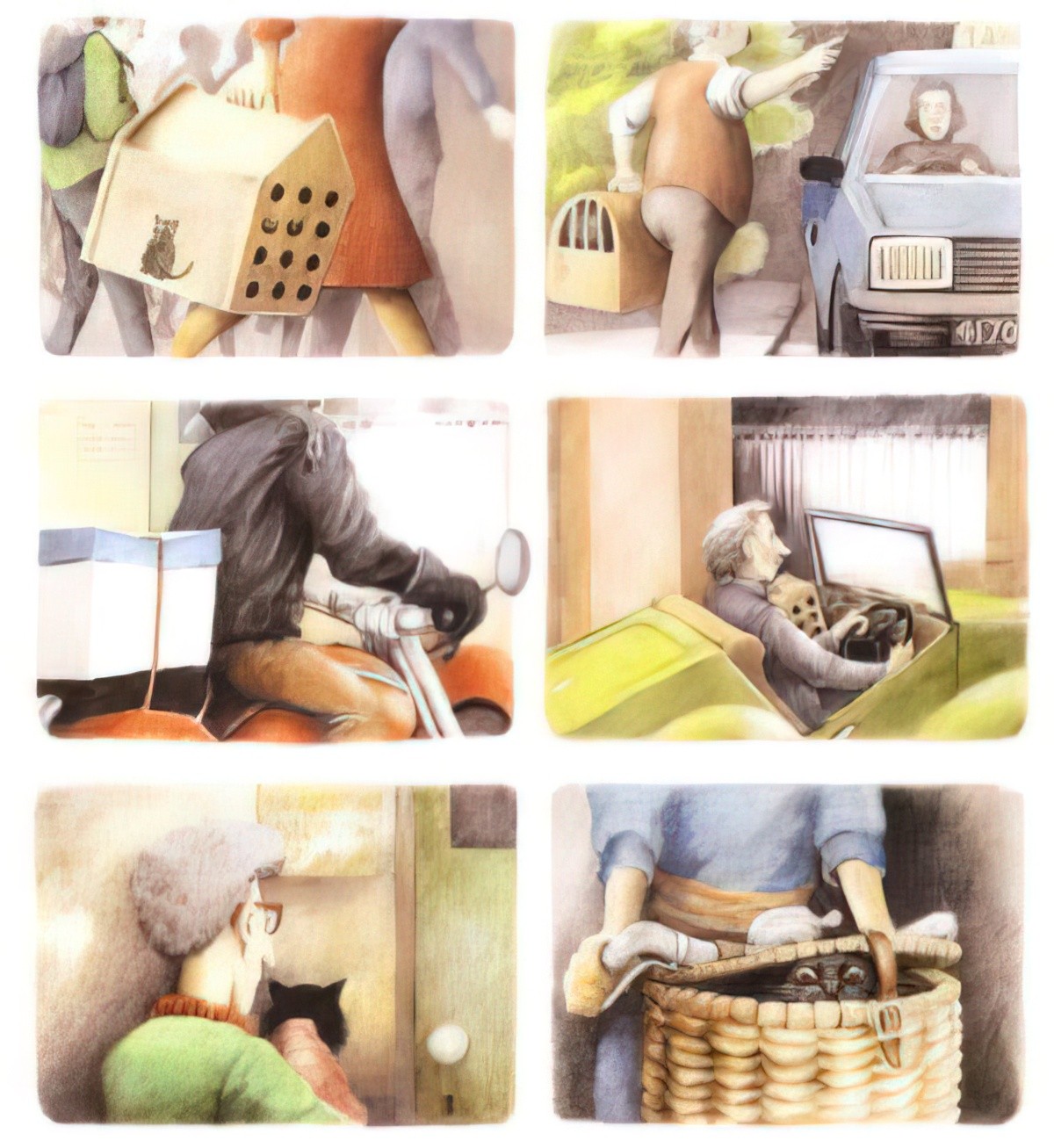

Many stories about pets contain a scene in a vet’s waiting area, where there will inevitably be a wide variety of different animals. (The vet is clearly always running very late!) Six Dinner Sid also includes the harrowing journey to the vet, or rather, journeys plural. The look on the cat’s face popping out of the basket contains most of the humour. By now he is clearly very annoyed. This montage of thumbnails also says something about human diversity, and shows young readers that there are many different sorts of people living in the world.

When Sid is made to take six different doses of medicine I worry for his health. That can’t be good.

But that’s not the intended takeaway, weakly lampshaded by the fact that he’s only taking it for good measure (it’s probably a placebo for the owners).

Think instead of the idiomatic expression ‘a dose of your own medicine’. Drinking disgusting medicine is punishment for Sid, for being disloyal and disingenuous. (For being a cat, basically.)

ANAGNORISIS

The mask comes off! The vet sees the same cat six times and makes a few phone calls. This is the big reveal.

As for the revelation, that is meant to be felt by the (adult) reader: When neighbours know each other, these things can’t happen.

NEW SITUATION

Because [in Pythagoras Place] everybody knew [about Sid’s six dinners] nobody minded.

Six Dinner Sid

Does this say something about the human condition? Do we mind things less so long as we know about them?

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

So what is really wrong with neighbours not talking to one another? The neighbours who don’t talk to each other are positioned as cranky in general, each one furious that Sid has been eating so many dinners. But the neighbours who do talk to each other are positioned as nice and charitable, and continue to feed Sid six dinners even after they learn of his tricks. Nasty people just don’t talk to each other, I guess?

One black cat tricking some neighbours is no biggie, but what if a true villain entered their midst? We can extrapolate that the street who talks to each other will be better equipped to ward off evil.

RESONANCE

Inga Moore is one of my favourite illustrators, and her work is particularly suited to stories such as The Wind In The Willows and The Secret Garden. And in Six Dinner Sid she demonstrates her ability to create slightly caricatured, comical characters as well as beautiful landscapes and buildings.

Six Dinner Sid was followed up with Six Dinner Sid: A Highland Adventure, which allowed Moore to paint quite a different landscape.

Six-Dinner Sid has been settled at Pythagoras Place for some time – but what happens when all his six owners decide to go on vacation at the same time? How will Sid get his six dinners a day?