“Singing My Sister Down” is a horror short story by Australian author Margo Lanagan. Find it in Lanagan’s collection Black Juice, published by Allen and Unwin. Black Juice was published in 2004, but “Singing My Sister Down” has proven especially resonant with readers, anthologised numerous times since. “Singing My Sister Down” is now a modern Australian short story classic.

Reading it again today, I stop halfway through and watch a Cookie Monster skit which has blessedly come through my Twitter feed. It’s just too much. I can’t think of many short stories this intense, though “Brokeback Mountain” is another (more so than the film).

OTHER creepy short stories TO COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The collection Black Juice is sold as young adult fiction, but I suspect that’s a decision especially relevant to small book markets like Australia, in which publishers convince high school English teachers all over the country to buy class sets. Another Australian author marketed as young adult is Sonya Hartnett, but I can’t pinpoint what, in the stories themselves, makes Hartnett’s work YA.

Anyhow, the marketing strategy works, because Black Juice has since become a set text for many Australian high school students.

Meanwhile, American students enjoy a story with a similar vibe: “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson.

I went to school in New Zealand. Our resonant horror short story in senior English class was “King Bait” by Keri Hulme — a similarly pessimistic commentary on what can happen when a small community comes together for an event.

But this is the most harrowing of them all. What makes “Singing My Sister Down” so damn memorable and scary? (And what makes it attractive to English teachers?)

THE HORRIFIC PLOT OF “SINGING MY SISTER DOWN”

NARRATION

The story is narrated from the point of view of a brother, who is charged with the task of playing music at his sister’s murder. We don’t know how much time has elapsed between the event and his retelling of it. He could be recounting the story many years into the future, or it might have just happened. He appears to be retelling the story as a way of understanding it. This is generally the case for storyteller narrators. All through the ‘ceremony’ he knew something was off, but was powerless to stop any of it.

SHORTCOMING

“Singing My Sister Down” is the story of a community rather than of an individual. The Moral Shortcoming of this community: Their traditions include abject cruelty.

The Shortcoming of each of its inhabitants: They cannot see a way out of this ritual. This is what they know. They don’t think to question it.

DESIRE

This is where “Singing My Sister Down” stands out over many other types of horror stories, some of which I don’t find scary at all.

There is no Desire to rescue this girl from the tar pit. (Not from the characters within the setting, that is.)

This defies our expectation of narrative in general. The vast majority of stories with a similar setting would take a different path. The twentieth century taught us to expect men rushing in to save a girl from sinking into quicksand.

But here, that hero trope is subverted. NO ONE is coming to rescue this girl. As reader, I feel this really frustrating glass wall between myself and the setting. There’s no way I can dive into the book and do something. Please, won’t somebody do something?

The desire of the family is to see Ikky accept her punishment of slow and sadistic death, and to make this murder (coded by the characters as fair and just punishment) follow the community’s customs around death, because they only get one chance to say goodbye.

OPPONENT

The Opposition that exists in “Singing My Sister Down” is not so much between the characters themselves. Technically, there is an opposition between Ikky and the rest of her community, because presumably she’d rather not be killed in this fashion. She has spent the recent days ‘sulking’ — understatement of the story.

Yet Ikky is grimly accepting of her punishment, indoctrinated by a culture which says this is the way things go. There is some mild opposition between Ikky and the aunt, who cannot face the tar-pit ceremony, but because the aunt remains off the page, this is a soft oppositional web.

There has been a big Battle which took place off the page — the axe fight in which Ikky killed someone. Off-the-page opponents can be scary too.

Regarding the hints about how Ikky got here: She was a newlywed. She killed someone with an axe. I extrapolate that she killed her new husband with an axe. Based on statistics around women who murder men, there was very likely a self-defence element at the base of Ikky’s crime.

In the 20 per cent of murders committed by women, over two-thirds were women killing men who had been abusing them.

This reader’s sympathy is therefore with Ikky.

This is a horrifically soft Opposition in this story, given the life-and-death situation. This in itself is a subversion. We expect people (and characters) to fight tooth and nail to save their own lives.

I’ve watched enough true crime shows to know that people usually do fight to the death, and will injure themselves severely in the hope of saving their own lives. Survival instinct kicks in. Another thing I’ve learned from a true crime show: Prisoners on death row don’t eat their last meals. Prison guards ask what they’d like and do an excellent job of preparing the meals. They know the prisoners won’t touch it, then they’ll eat it themselves. This was mentioned in a documentary about a serial killer — presumed psychopathic. This guy stood out from all the other (probably psychopathic) prisoners facing imminent execution in America because he indeed ate his last meal, and seemed to enjoy it. Evidence of his lack of humanity. (I figure this is why baddies so often eat apples and sandwiches after committing horrific crimes in stories. Normal people couldn’t eat a thing at a time like that. In fact we’d do the opposite of eat — we’d throw up.)

Ikky in “Singing My Sister Down” eats her last meal of crab meat as she sinks into the tar pit. I don’t believe this is realistic, but it is horrific. And mimesis is over-rated — I believe there is a symbolic reason for the crab meat, and also for her eating it.

THE SYMBOLISM OF CRUSTACEANS

What’s with the crabs, I wonder? I just read another short story with crabs by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, “A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings“, in which the magical realist setting opens with an invasion of crabs coming in from the sea to inhabit the human habitat. In that story, land meets the sea as earth meets heaven (an angel falls to earth and is not as ‘angelic’ as everyone expected).

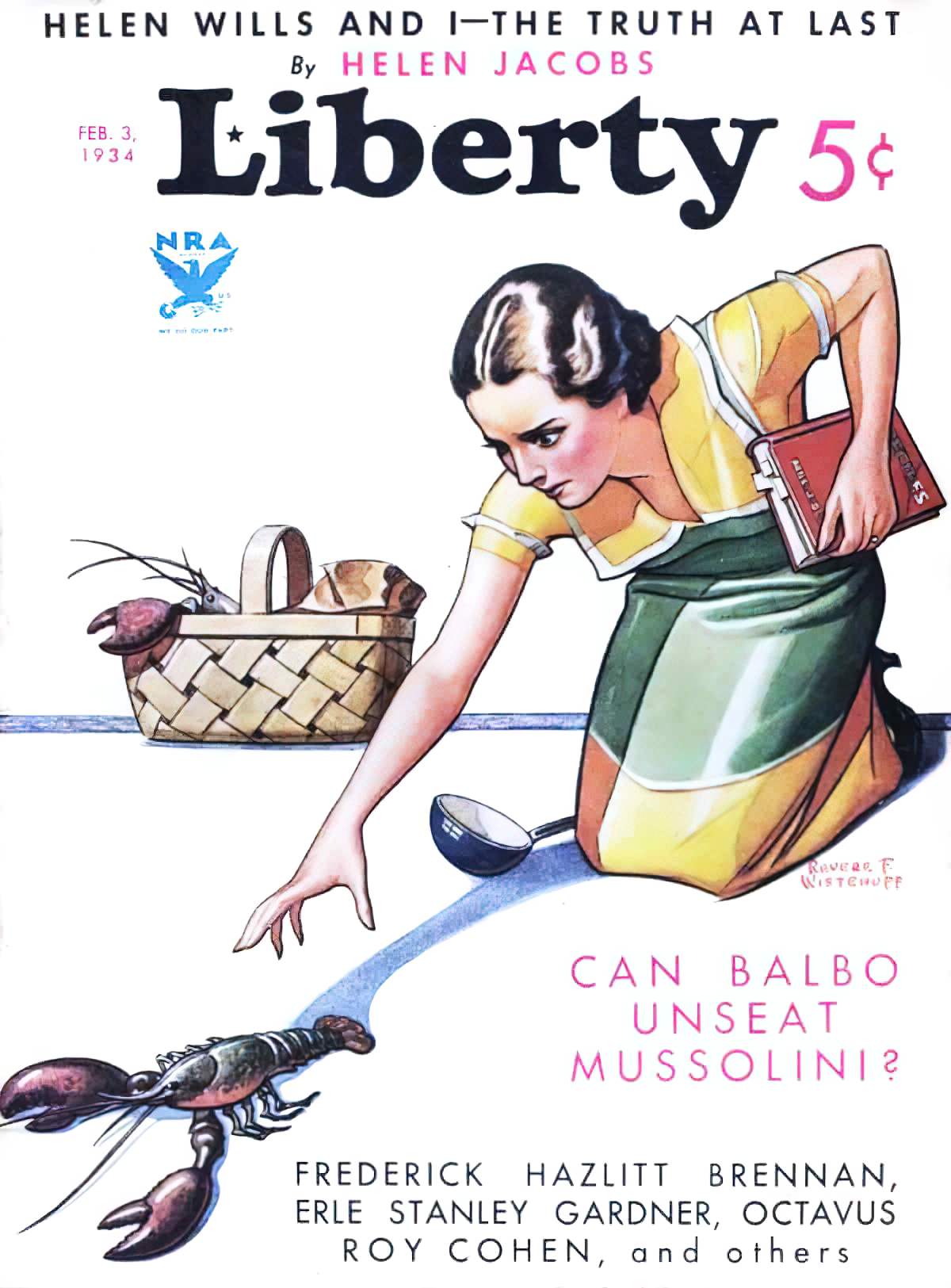

But in “Singing My Sister Down”, is there any symbolic significance regarding the crab meat? I personally find crabs creepy. They’re like the huntsman spiders of the sea. They have too many legs. They walk sideways. Their eyes are entirely black and stick up on stalks. There is nothing cute about a crab. Worst of all are the pinchers. Even a cooked crab gives me the willies.

Actually there is one thing worse than crabs on the beach. And that’s live crabs dropped alive into boiling water. I have no empathy for a crab walking along the beach, but as soon as a chef throws a crustacean into water, suddenly I’m horrified.

Time and again, throughout history, the same pattern happens: Studies eventually show that animals apart from humans feel far more than we thought they did. Same with crabs.

Normally this discussion is around lobsters.

Robert Elwood once boiled a lobster alive – lobsters being one of the few creatures we eat that we are allowed to slaughter at home. It is the usual way to kill, and cook, them. “Would I boil a lobster now?” asks Elwood, emeritus professor at the school of biological sciences at Queen’s University Belfast, referring to the work he has done for more than a decade on crustaceans and pain. “I wouldn’t. I would kill it before boiling.” […]

The argument is: we know the areas involved in pain experienced in humans; if you don’t have those areas, you can’t feel pain. But it’s quite clear that, in evolution, completely different structures have arisen to have exactly the same function – crustaceans don’t have a visual cortex anything like that of a human, but they can see. Given the evolutionary advantage of experiencing pain, there is no reason to assume they should not have this protection against tissue damage.”

Is it wrong to boil lobsters alive? from The Guardian

Why should this even be surprising to us at this point?

It’s illegal to boil crustaceans alive in my home country of New Zealand; Australia is progressing more slowly, state by state. When “Singing My Sister Down” was published, this worldwide trend had yet to begin.

Do I think that’s the main message of “Singing My Sister Down?” That we shouldn’t cook crustaceans alive because we wouldn’t cook a human alive in a tar-pit? Nope. Don’t think that. But that’s where the crab thing took me.

Crustaceans aside, the most disturbing opposition in “Singing My Sister Down” exists not between the characters themselves, but between the story and the audience. We desperately want someone to step in and stop this from happening. Nobody does.

We might say the opposition = the setting. There is a freaky robo-fate to how this ceremony plays out, akin to the ‘mechanical behaviour’ trope found so often in horror.

Weirdly, the ‘mechanical behaviour’ trope is found also in comedy. A comedy example is Roy asking “Have you turned it off and on again?” on The I.T. Crowd. At one point the ‘mechanical-ness’ of this act is exploited in full, when Roy hooks up an actual tape recorder to do his entire job. Most commonly, the character with mechanical behaviour has an element of the fussbudget about them.

In horror the mechanical behaviour of the villain exposes his lack of humanity. You can’t reason with such a character. Worst of all, you can’t kill something mechanical — horror monsters keep coming back and back and back.

But here, the setting itself — the culture of this messed up little community — is the force which propels this girl’s family to go ahead with her murder. This, in my view, is the most horrific form of mechanical behaviour there is.

PLAN

There is no plan to rescue Ikky. The Plan is to carry out the tar-pit sinking in customary fashion. The bulk of the detail in “Singing My Sister Down” is around the rituals, and a blow-by-blow description of the sinking.

The narrator might easily be describing a wedding, which also involves music and flower wreaths. Indeed, there has recently been a wedding.

‘Well, this party’s going to be almost as good, ’cause it’s got children. And look what else!’ And she reached for the next ice-basket.

This juxtaposition evokes unease in the reader. Births, deaths, marriages… all completely different things… all involve similar ritual.

BIG STRUGGLE

We know what the climax is going to be, which is why it’s so horrible. It’s one thing to be almost ‘cuddled’ warmly by the tar. It’s another thing to suffocate in the damn stuff.

It is nightfall before this happens. Because the story is narrated by the brother onlooker, his memory of the exact moment is clouded. ‘… and they tell me I made an awful noise…’ The setting seems to come alive — setting becomes a character in its own right with the flowers ‘nodding in the lamplight’. The setting itself has already been established as the main opposition (the cultural milieu rather than, say, weather elements a la a disaster story). So an ‘aliveness’ is entirely appropriate at this point.

ANAGNORISIS

If we were expecting an ending with a sense of hope, this story lets us down. No one steps in to save this young woman.

The narrator says finally that he ‘will never understand’. He experiences no Anagnorisis, at least not the kind we hope he will have — that this was a terrible thing that happened. What if he did realise that? What if he realised the injustice of it? It’s not in his best interests to think too hard about this ritual, otherwise he might spend the rest of his life berating himself for failing to step in and save Ikky.

By dashing our expectations, the reader may instead experience the revelation — that when communities come together, humans are capable of the most heinous acts. But we know that already, perhaps.

There is nothing in this story that hasn’t happened somewhere at some point in human history. The details may be different, but during the European witch craze, women (and across Europe, plenty of men) were burned alive with the consent of entire communities. We have far more recent examples, most notably from WW2, but into the present.

DEATH

Characters in stories die frequently. Sometimes it’s no more than a plot feature. In other stories, death becomes thematically significant. This is one of those stories.

The sinking itself takes place over a day, thereabouts. Symbolically, stories which take place over 24 hours tend to be a compressed insight into a single human lifespan. This is how Ikky can eat. We all eat to stay alive, all the while knowing we’re still going to die.

More on that, then. At the beginning of this story, Ikky, her family and her entire community knows she is going to die. Slowly. Horrifyingly slowly. But isn’t that the case for all of us? We all know that we ourselves are going to die. Not today, probably, but someday. Life itself is a horrifyingly slow death.

We don’t know this as children. Even after learning everybody dies, children have difficulty with the concept that they themselves will one day be dead. We can’t imagine not existing. We have equal difficulty imagining not being born. If you have kids, they’ve probably asked you: “Where was I when I wasn’t born?”

Then we hit the teen years, or perhaps the 20s, and the concept of death really sinks in. (Heh.) Heidegger called this part of human development Being-toward-death: The ‘moment’ (more likely an extended period) in which we come to understand that we ourselves will die — that from the point of conception we’ve all begun the journey towards death.

Marketing reasons aside, this aspect, even more than the age of the characters, is perhaps what makes “Singing My Sister Down” a genuinely young adult story.

NEW SITUATION

Since the narrator has learned nothing, this tradition of tar-pit murders will continue inside the setting.

But I believe this narrator is wilfully avoiding his Anagnorisis — that he could’ve done something to stop it.

Wilful ignorance is another fascinating aspect of being human, and “Singing My Sister Down” could be used as a deep-dive into that.

Instead, let’s go nitty-gritty.

THE CREEPY NARRATIVE VOICE OF “SINGING MY SISTER DOWN”

“The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson shocked and angered many American readers when first published because the opening seemed to promise a cosy depiction of a bucolic community coming together for an annual event, then did the old switcheroo and turned into a horror. Part of this was to do with the narrative voice — conversational and cosy.

I doubt the reader would be fooled by Lanagan’s story, which is creepy from the get-go. I suspect the diction feels creepy partly because of the uncanny valley effect — English, but not quite English. The voice feels almost translated from an unknown language, and because we don’t know where this is set, or which language is spoken, it could be anywhere.

It could happen where you are, right now.

How does Lanagan create this creepy narrative voice?

LEAVING OUT WORDS – JUST LEAVING THEM OUT

‘Yes, Bard Jo.’ Dot sat himself to listen.

I would most naturally say ‘Dot sat himself DOWN to listen.’ But this is an idiomatic expression and we don’t really need the ‘down’ of ‘sit down’, do we? I wonder if she crossed it out during a revision or if she never wrote the word in the first place.

invented WORDS

We don’t know how she fits all that into her days, but she does, and all the time she’s humming and thrumming.

The onomatopoeic word ‘thrumming’ creates a nice rhyme, and lends the voice a poetic feel. The word seems to vibrate right through you, in a mimetic way.

Also: ‘tea-tent’, ‘a mystery child’, ‘his house’s smoke hole’ (obviously in lieu of a chimney), middlehood (instead of ‘middle age’), and so on and so forth, right the way through the story.

INSERTING PREPOSITIONS AND ARTICLES IN UNEXPECTED PLACES

he wears the comfortable robes

Note use of ‘the’. I might have written ‘he wears comfortable robes’, but by making use of ‘the’, it is taken for granted that there is a division of robes – some are comfortable and others are probably worn on formal occasions. ‘The’ adds to the verisimilitude of the story by suggesting everyone is already in possession of this fact.

OLD WORDS IN NEW COMBINATIONS

Dot saw the women bent to the vegetable fields.

In my dialect of English, I have never used the phrase ‘bent to’. I would probably make use of some phrase more wordy, like ‘Dot saw the women bending down to tend the vegetable fields.’ But I like Lanagan’s phrase much better. Not only does she manage to convey an idea succinctly, she creates a new ‘idiomatic expression’ – one that’s not idiomatic in OUR world, but one which the reader can easily take as idiomatic in this fantasy world of the story. Since the phrase is slightly out of whack in English, it’s like this story has been translated from another language. This adds to the fantastic mood.

Also: ‘talking wisdom with the Bard’, ‘made a bitter laugh in his throat’ (not ‘laughed bitterly in his throat’, which would be hackneyed), ‘weaves song stuff’, ‘grilled bean pats’ for breakfast.

CREATIVE GRAMMAR

And when that’s quieted, we can hear Anneh and Robbreh again, steady in their song.

Sure, ‘quiet’ is both an adjective and a verb in English, but when it’s a verb it’s usually used as a transitive verb (i.e. it takes an object) as in, ‘The teacher quieted the students’. When ‘quiet’ is used as an intransitive verb (i.e. without an object), as it is here, it’s usually used in the phrase ‘quiet down‘, e.g. ‘The students quieted down.’ So Lanagan has used a transitive verb as an intransitive verb and dropped the bit which makes it a phrasal verb.

Also: ‘they SAW television’ (instead of watched).

MORE

- Kim Hill interviewed Margo Langan on Radio New Zealand back in 2011. Kim gave special mention to “Singing My Sister Down” as particularly harrowing.

- I’ve written more extensively about Being-toward-death in a post about the movie I Kill Giants, a perfect YA example.