GROUPS OF FIVE TECH GUYS

The creators of Silicon Valley reveal to their audience early in the show the thinking behind their ensemble of “five guys”. This may or may not have some realworld application — I don’t know the real Silicon Valley. But even if it doesn’t ring one bit true, every time we do see this particular ensemble in real life tech teams, fans will now think of Silicon Valley, the fictional comedy show. This ensemble will seem more common than it ever was before. (Such are cognitive biases.)

Gavin Belson: It’s weird. They always travel in groups of five. These programmers, there’s always a tall, skinny white guy; short, skinny Asian guy; fat guy with a ponytail; some guy with crazy facial hair; and then an East Indian guy. It’s like they trade guys until they all have the right group.

Season One

The audience is encouraged in this scene to map the main cast of Silicon Valley onto these tech archetypes as observed by tech baddie/opponent Gavin Belson. The writers make us use our brains a little bit:

- The tall skinny white guy: Jared, or is it Richard?

- The short, skinny Asian guy: Big Head might be mistaken for this guy from a distance, but it’s actually Jiang-Yang. Big Head will soon leave the group, comically turning Gavin Belson’s assessment into a prediction.

- The fat guy with a ponytail: Erlich doesn’t have a ponytail, but he is in the habit of clipping his leonine mane aside when eating noodles (often), or when sitting down to code (rarely).

- Some guy with crazy facial hair: Gilfoyle, I guess, but could also be Erlich.

- The East Indian guy: Dinesh, who is in one episode mistaken for Latino.

Not included: Richard, because Richard is ‘the rounded character’ who surrounds himself with archetypes. Richard tries on each of these characters in an attempt to concretize who he is. He can’t actually function without these guys, and these guys can’t function without each other. They’re like a hive mind. Or, as commentators have put it: They are each different aspects of the same person.

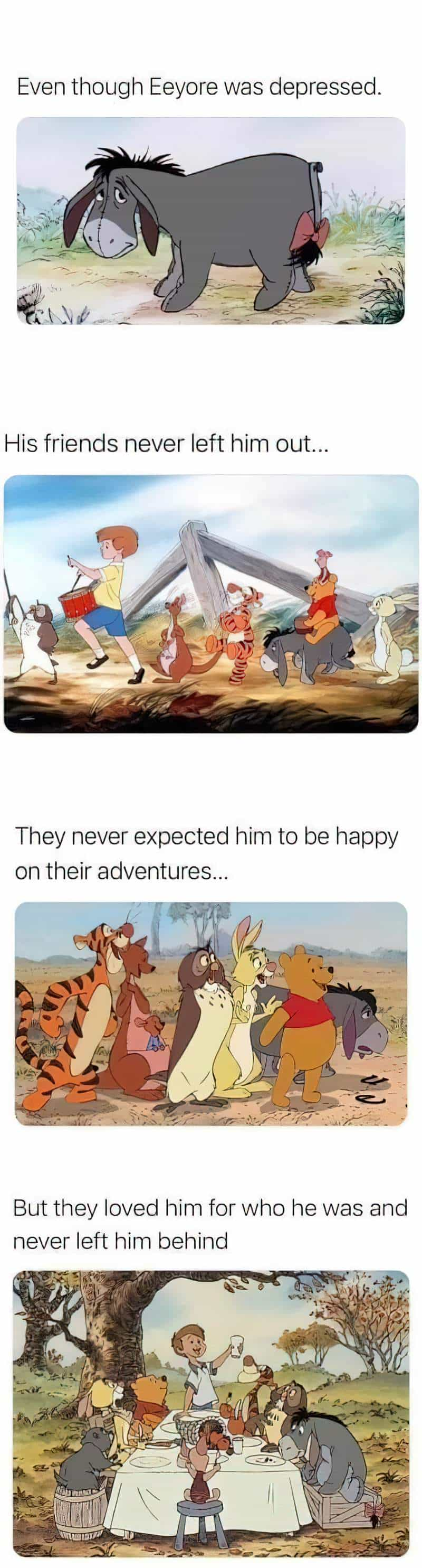

Critics of children’s literature have been considering ensembles in this way for decades. Winnie the Pooh is an excellent example of the ‘ensemble as parts of a collective unconscious (protagonist):

POOH BEAR

Pooh is the bland, confident, mystic child.

PIGLET

Piglet is the small, nervous but very brave child. Piglet moves in with Pooh, which might be seen as a fusion of character. Piglet eats acorns. Piglet is used to mock cowardice.

TIGGER

Tigger is the wild child. He is fussy about his food. His attempts to find suitable food for himself is a search for identity. He must find his place in the hierarchy of the Forest (remember, the Forest equals childhood). Tigger is the only animal who doesn’t have a house of his own and stays with Kanga. This emphasises his smallness. (Not his physical dimensions but his general bouncy demeanour, which is childlike.) Normally — if he were a real animal — he would have gobbled up Kanga. This further disarms him. He is at the ‘pre-mirror’ stage of child development, and doesn’t recognise his own reflection. He is a baby who has just been weaned, tasting his mother’s different foodstuffs. Milne uses Tigger to mock verbal hypocrisies of greed.

ROO

Roo is the baby, and critics find it difficult to say much interesting about Roo.

RABBIT

Rabbit often thought to represent is the egocentric, sarcastic adult. Rabbit is the most conservative part of the collective protagonist. He is against change. He wants to get rid of Kanga and then Roo, then Tigger. But Rabbit is also the most childish. He is the most reluctant part of the child. This is a stubborn child who has made up his mind and is unwilling to change. (Perhaps he is really a very old man.) Rabbit is used to mock polite etiquette.

OWL

Owl is the pretentious and insecure egocentric adult.

KANGA

Kanga is the loving but firm mother.

EEYORE

Eeyore — together with Owl, Eeryore is closest to the world of adults. This is partly symbolised by his food. Eeyore eats thistles, rather than the sweet foods of childhood.

The idea of the collective subconscious — or in fiction, the collective protagonist, originally comes from Jungian thought. Do you find yourself mapping Pooh characters onto the Silicon Valley characters? A universal pattern is beginning to emerge, right?

Matt Bird, of the Cockeyed Caravan (Secrets of Story) blog has built on Jung’s archetypes, especially as it relates to contemporary storytelling for adults.

I’d like to add to Matt Bird’s theory a little with this observation: In comedy ensembles, much comedy derives from one character thinking they are another character. The best comedy seems to come from a Gut character who believes himself to be the Head character.

- In Silicon Valley, Erlich Bachmann is a Gut character who believes himself to be the Head. He frequently takes the team into deeper problems, e.g. by commissioning a lewd logo which incites anger from their suburban neighbours, or by taking the dating concept of ‘negging’ and applying it in business meetings.

- In The Wind In The Willows, Toad is the Gut character who believes himself to be smarter than Ratty, who is the actual Head.

- In the animation series We Bare Bears, Grizz is the gut character who always makes the plans, and reminds me of Erlich Bachmann in many ways.

THE THREE NERDS ENSEMBLE OF THE 1990s/2000s

The five guy ensemble of Silicon Valley (2010s) is itself a more contemporary update on a trio I’ve noticed in a number of earlier shows about ‘nerds/geeks’.

Freaks and Geeks is a good show to recall at this point, partly because the actor who plays Gilfoyle also played a nerd (‘geek’) on cult hit Freaks and Geeks. However, he is not playing the same variety of nerd. Note that these trios are male. But the distinctive features of the earlier trio are not based on physical and racial characteristics. Instead, they mainly reflect contrasting attitudes towards women and sex.

THE TEMPORARILY OSTRACISED NERD

The geek who has been ostracised from the popular crowd for some reason which probably won’t endure, and which is no fault of his own. In Freaks and Geeks this character is Sam. He can’t be part of the popular crowd because he is late to adolescence. (A younger actor was cast for the role of Sam.) Sam is a rounded empathetic character whose naivety regarding dating and girls is common to everyone at some point.

THE CONTENTED NERD

The geek who is ostracised due to his nerdiness but is nonetheless confident and happy about who he is. This guy replaces a passion for romance with other passions. In Freaks and Geeks, Martin Starr is playing Bill, who is a lovable geek, somehow confident in who he is, or will be once he’s made it out of high school. A few scenes with Bill comically utilise this aspect of his characterisation. We see other teenagers fretting about their social lives while Bill sits at home on his own clearly enjoying daytime TV while eating a snack. In another scene, the boys prank each other by making the most disgusting milkshake they can think of. Unexpectedly, Bill finds it tasty. This is Bill’s attitude to life in general. He’s content with who he is, and whatever he happens to be drinking. With increasing ‘autism awareness’ (‘acceptance’ is a long way off), these nerd archetypes tend to be coded by audiences as autistic. The danger is that this particular autistic archetype will subsume a broader conception of autism. Coding this guy as ‘the autistic geek’ may lead to the misunderstanding that ‘the autistics are happy without friends because autistics have special passions and don’t need their people friends like the rest of humanity’. Also, it promotes the misguided statistic that autistic people are male, with special interests which present their brains as computers, only on a meaty substrate. This is not an empathetic or nuanced presentation of autism; it is a comedy archetype.

THE MISOGYNIST NERD

Unfortunately, these trios also tend to include an Elliot Roger archetype, who I fear are made far too deliberately lovable by their writers.

In Freaks and Geeks we have Neal Schweiber. Rather than embracing his nerdiness, he is frustrated by it. He is especially frustrated that he can’t attract any girls. He is smart and decent looking, but his sense of entitlement repels romance. Martin Starr, who played the lovable Bill on Freaks and Geeks is now the creepy nerd on Silicon Valley. My heart breaks just a little, because I wanted to see what happened to the adult Bill. (I’m pretty sure he’s perfectly happy with his life, whatever he ended up doing.)

Note that these guys have nothing in common with each other, aside from a shared ostracisation from the mainstream. They wouldn’t choose to hang out together, surely, because they are morally different.

A similar cast of nerds is utilised in British transgression comedy The I.T. Crowd. These characters are thrown together because of their work.

- Moss has no game, and is completely fine with that. He has his tech gear to keep him amused and occupied.

- Roy is the creep, and I believe he’s portrayed as more lovable than he really should be. I’m not even convinced the creators realise how much of a creep Roy is. (The creator of The I.T. Crowd has recently revealed significant bigotry, directed at the trans community.)

- There’s no ‘normal guy’ down in the basement, but they send down a ‘normal girl’ instead, in the form of Jen. Jen is not a nerd by Moss and Roy’s standards. The audience understands she’s enjoyed social capital until now. Her strange side (which was always hidden) is about to reveal itself in the underworld hell of the basement.

I can’t stomach The Big Bang Theory, but it may be interesting to consider the nerd ensemble on that show, and its ‘lovable’ presentation of misogyny coupled with childlike naivety.

THE INSIDE-OUTSIDER

Many comedy series utilise a character who is not part of the in-group, but is always hanging around. Silicon Valley makes use of this character as well.

- Kramer from Seinfeld

- Winslow T. Oddfellow from CatDog

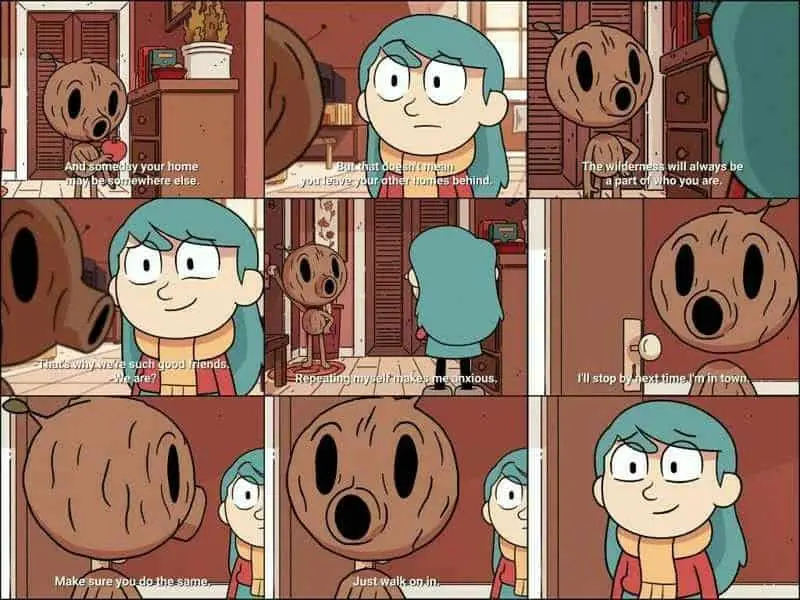

- Woodman from Hilda

These characters are not well-liked by the ‘main’ cast, though they appear so frequently, we forget that they are part of the main cast. They commonly (though not always) treat the main character’s living quarters as their own, walking in and out as if they own the place, ignoring messages that they aren’t welcome. Sometimes they’re simply a quirky person who will never be fully accepted by the in-group because they’re just a bit too odd.

In Silicon Valley the inside-outsider is Jian-Yang. It appears that he doesn’t understand English, but it’s gradually apparent that he has a much better grasp of English (and of his circumstance) than he liked to let on. He is therefore a trickster character who tricks Erlich into ‘letting’ him stay in his house free of charge for a further year longer than he is welcome.

THE USE OF INSIDE-OUTSIDER CHARACTERS

They provide a low level of conflict which can come in useful any time the writers see fit. Their oddness serves to make the oddball main characters look less odd, and therefore more empathetic to the audience.

THE FEMALE MATURITY PRINCIPLE

Shows about tech nerds are without fail full of ‘hipster’ misogyny. I say ‘hipster’ because there’s an assumption that everyone in the audience will recognise misgyny for what it is, and judge it negatively accordingly.

However, this argument falls flat when the misogynistic characters get the ‘best’ lines, and by ‘best’, I mean the most witty, delivered with the best timing, demonstrating the quick mental processing powers of these misogynistic jokesters. In Silicon Valley, both Erlich and Gilfoyle impress us with their wit, and both of them are misogynistic, frequently. It’s naive to think that these jokes don’t reinforce misogynistic humour, ergo misogyny itself, as well as poking fun at the misogynistic characters, who come up trumps every time.

Some of these showrunners seem to think that there’s a mathematics to misogyny, that it can be cancelled out with the addition of a capable girl.

Monica Hall is the real Head character of Silicon Valley. In stories with one girl among many boys, the girl is frequently the Head character. She really knows what’s going on, even when one of the boys thinks he knows what’s going on, and tries to override her opinions. This is undoubtedly a critique of misogynistic structures as they play out in real life. But when the fictional girl is picked time and time again to be ‘the Head’ character, the unintended consequence is this: Girls make good mothers. That’s the message. When the girl is the sensible one every single time, girls do not get their own character arcs.

When another female character is added to the cast of Silicon Valley, we laugh at Jared as he tries to accommodate Carla by making her friends with Monica. Carla is given a line that must have come from women in the first place: She complains that in every workplace with two women the women are expected to be friends.

In the end, Carla winds up suing the guys, not for sexual harassment, but for a ‘satirical take’ on sexual harassment: Carla sues Pied Piper for Jared’s insistence that she become friends with Monica. In the end, the message for the audience is the same old, same old: One woman in a startup is manageable; add another and there will be problems.

This is an example of failed subversion.