“The Wrysons” is interesting as a study of writing technique because it is a story with the theme of ‘lack’ running throughout, and Cheever masterfully chose to employ some narrative techniques which are themselves about describing not what did happen but what didn’t, and what might have.

Apart from The Bella Lingua, which is set in Italy, this and the preceding number of Cheever’s short stories were all set in his famous Shady Hill. Did Cheever want to live in a place such as Shady Hill? I suspect he would have called the whole place ‘phony’, and in The Wrysons he once again dips into the idea that in the suburbs where everything seems perfect, there must be rot beneath the veneer. In fact, he has gone much further with this in other stories such as The Housebreaker of Shady Hill, in which a man burgles his own neighbours (I guess I didn’t really spoil anything for anyone there — it’s all in the title!), and in “The Enormous Radio”, which is not set in the suburbs but is all about the feeling that you’re living two steps away from terrible, terrible happenings.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE WRYSONS”

A suburban couple with one daughter have zero interests except the wish for their comfortable suburb to stay exactly the same. The only difficult thing about the wife’s life seems to be her regular unsettling dreams in which someone explodes a hydrogen bomb and causes the end of the world. She also dreams that she poisons her own daughter. The husband thought he felt nothing when his mother died, but deals with her death by occasionally waking in the middle of the night and baking a cake in the kitchen to remind him of his childhood, in which his mother and he would bake together to create a cosy atmosphere. The husband is unaware of his wife’s dreams; the wife is unaware of her husband’s cake-baking habit, until one night he burns the cake, wakes her up, and they go back to bed more confused about the world than ever.

SETTING OF “THE WRYSONS”

Place

If you’ve read other, better-known stories of Cheever you’ll be familiar with this place in middle to upper-class America — it’s not a real suburb in any real town, but Cheever returns to it as a setting time and again. Perhaps his most famous story set in Shady Hill is The Swimmer. This family lives in the fictional Alewives Lane. They have a nice garden. ‘They were odd, of course’, writes Cheever — and with a masterly use of ‘of course’ we are to take it for granted that everyone who might seem ‘normal’ is actually harboring a hidden or overt eccentricity.

Time

It’s significant in this story that at the time this story was written, the baking of cakes in the home was strictly a feminine task, a point of pride, in fact, and for a married man to don an apron and make a cake — a Lady Baltimore cake, no less — would have been thought terrible emasculating. Indeed, when the wife is finally woken by the smell of burning, she admonishes the husband by telling him he should have woken her if he was feeling hungry, as if the kitchen was her own private space.

This is also a time — difficult for those of us who are younger to imagine — in which people genuinely feared a hydrogen bomb ending everything.

CHARACTERS IN “THE WRYSONS”

We are told about the Wrysons in the opening paragraph. Of all the things a writer might choose to bring to the fore, what should it be? Cheever has chosen to give us the detail we might know of this couple if we lived in the same suburb with them. At this point we don’t know anything about what goes on inside their home, only that which we can garner from normal interactions with neighbours:

THE WRYSONS WANTED things in the suburb of Shady Hill to remain exactly as they were. Their dread of change-of irregularity of any sort-was acute, and when the Larkin estate was sold for an old people’s rest home, the Wrysons went to the Village Council meeting and demanded to know what sort of old people these old people were going to be. The Wrysons’ civic activities were confined to upzoning, but they were very active in this field, and if you were invited to their house for cocktails, the chances were that you would be asked to sign an upzoning petition before you got away.

Although I have a general idea of what ‘upzoning’ entails, I looked it up and learned that upzoning is:

The practice of changing the zoning in an area typically from residential to increased commercial use. This is a controversial practice because upzoning allows for greater density and congestion in the area which affects the current occupants. The term can also apply when changing the zoning to limit growth and density.

We know that the Wrysons are against the upzoning, hoping to keep this upper-middle class suburb from commercial enterprise, even of the most ‘residential’ in nature, e.g. the old people’s home.

The Wrysons were stiff; they were inflexible. They seemed to experience not distaste but alarm when they found quack grass in their lawn or heard of a contemplated divorce among their neighbors.

DONALD WRYSON

Donald Wryson was a large man with thinning fair hair and the cheerful air of a bully, but he was a bully only in the defense of rectitude, class distinctions, and the orderly appearance of things.

Donald has a ‘jackass laugh’ which tends to alienate people, including his wife, who fears that if she were to tell him about her dreams he would only respond with his horrible laugh. A character described as ‘jackass’ isn’t likely to be endearing, though I find him to be an empathetic character despite his flaws; this is probably because his general unpleasantness is only outlined by our unseen narrator, whereas the actual scenes show his relationship with his dead mother and how his biggest secret in life is baking cakes in the middle of the night (daring to go against gender norms), and scenes are always more powerful than overviews.

IRENE WRYSON

I always find it interesting that it is possible to describe a woman as either ‘attractive’ or ‘unattractive’ (or somewhere in between, as here) and it is expected the reader knows exactly what is meant by that. This is probably due to the existence of the Western Feminine Beauty Standard, which is seen everywhere in the media, and which we all understand. (Compare with the description of Donald Wryson, whose attributes are described for the reader to judge.)

Irene Wryson was not a totally unattractive woman, but she was both shy and contentious, especially contentious on the subject of upzoning.

We are to believe that Irene is equally bereft of real life purpose as her husband.

MRS WRYSON

Sometimes the characters who are not ‘on stage’ in the story are just as significant as those who are. For example, Donald and Irene’s daughter Dolly is not really a part of this story — just mentioned. The name seems significant: In the story she is mute and a prop, a kind of doll to make this little family into a ‘real’ family, in an milieu when children were requisite. Dolly is important to Irene and her dreams, and Donald Wryson’s mother is important in explaining why he bakes the cakes.

Mrs. Wryson had few friends and no family. With her husband gone, she got a job as a clerk in an insurance office, and took up, with her son, a life of unmitigated melancholy and need. She never forgot the horror of her abandonment, and she leaned so heavily for support on her son that she seemed to threaten his animal spirits. Her life was a Calvary, as she often said, and the most she could do was to keep body and soul together.

She had been young and fair and happy once, and the only way she had of evoking these lost times was by giving her son baking lessons. When the nights were long and cold and the wind whistled around the four-family house where they lived, she would light a fire in the kitchen range and drop an apple peel onto the stove lid for the fragrance. Then Donald would put on an apron and scurry around, getting out the necessary bowls and pans, measuring out flour and sugar, separating eggs. He learned the contents of every cupboard. He knew where the spices and the sugar were kept, the nutmeats and the citron, and when the work was done, he enjoyed washing the bowls and pans and putting them back where they belonged. Donald loved these hours himself, mostly because they seemed to dispel the oppression that stood unlifted over those years of his mother’s life-and was there any reason why a lonely boy should rebel against the feeling of security that he found in the kitchen on a stormy night? She taught him how to make cookies and muffins and banana bread and, finally, a Lady Baltimore cake.

THEME OF “THE WRYSONS”

Appearance does not match reality.

This is not a particularly enlightened observation of theme on my part — I feel like almost all stories have this exact theme.

[The Wrysons] lived in a pleasant house on Alewives Lane, and they went in for gardening. This was another way of keeping up the appearance of things, and Donald Wryson was very critical of a neighbor who had ragged syringa bushes and a bare spot on her front lawn. They led a limited social life; they seemed to have no ambitions or needs in this direction, although at Christmas each year they sent out about six hundred cards.

But what else does Cheever do with it? He doesn’t go in for melodrama — this is no American Beauty or Desperate Housewives, in which the things happening in your own suburban street really are pretty surprising. No, this is simply a story about a wife who has bad dreams, and a man who bakes cakes in the middle of the night, which in the scheme of things isn’t too shocking. What Cheever does here is describe the feeling of being chased by those judgey eyes, those of the bearded man with garlicky breath, and how the need to keep up appearances can impact your life. Although the Wrysons go the extreme effort (and expense) of sending out 600 Christmas cards each year, the side-shadowing paragraph suggests that even if they both died, the return Christmas cards would keep coming to them — if the senders don’t even know they’re dead, what do they really care that they’re alive? The cards are nothing more than a formality.

People are inherently unknowable because there will always be gaps between us.

Because of the gaps between them, the story ends with the husband and wife knowing very little about each other than they knew before; this even though they’re married and presumably know each other better than anyone else in the world. The Christmas card exchanges hypothetically continue because it’s impossible to keep up with 600 acquaintances (a theme particularly relevant in the modern age of social media ‘friending’.)

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE IN “THE WRYSONS”

AN IMAGINARY CHARACTER

This imaginary character — imagined by the characters, in fact — is described at the beginning of the story and is mentioned again right at the end, and has the purpose of lending a sense of closure to the story, but more importantly, conveying the theme of what is now known as the ‘imaginary audience’ — heightened, no doubt, in the age of the Internet, in which everything you do is influenced by the notion that someone is watching you and judging. John Cheever personifies this feeling with a rather unflattering thumbnail character sketch:

They seemed to sense that there was a stranger at the gates-unwashed, tirelessly scheming, foreign, the father of disorderly children who would ruin their rose garden and depreciate their real-estate investment, a man with a beard, a garlic breath, and a book.

And again the stranger is described in the final paragraph, in which the characters almost have some sort of epiphany about each other, but not quite:

[Irene] turned off the oven, and opened the window to let out the smell of smoke and let in the smell of nicotiana and other night flowers. She may have hesitated for a moment, for what would the stranger at the gates—that intruder with his beard and his book—have made of this couple, in their nightclothes, in the smoke-filled kitchen at half past four in the morning?

DESCRIBING WHAT IS NOT THERE

Following on from creating a character who doesn’t really exist, Cheever describes the Wrysons’ house in general by homing in on what is not there rather than what is:

There was hardly a book in their house, and, in a place where even cooks were known to have Picasso reproductions hanging above their washstands, the Wrysons’ taste in painting stopped at marine sunsets and bowls of flowers.

It is unusual to describe a place by what is not there, but it’s in keeping with the theme: The bearded stranger is not there, either. What else is not in the house? Communication between the couple — tenderness, intimacy. There is no real purpose to their lives, apart from as parents to Dolly. Being interested in upzoning does not mean their minds are actively engaged in anything of lasting worth. Instead of longing for what could be, they long for what is not.

Years later [after his mother’s death], when Donald was living alone in New York, he had been overtaken suddenly, one spring evening, by a depression as keen as any in his adolescence. He did not drink, he did not enjoy books or movies or the theatre, and, like his mother, he had few friends. Searching desperately for some way to take himself out of this misery, he hit on the idea of baking a Lady Baltimore cake.

CAKE SYMBOLISM

A Lady Baltimore cake is a particularly well-presented, fussy type of cake, which is assembled in creamed layers and then iced all over and often further decorated. This is a cake that is presented to impress; its appearances are all important.

When the cake was done he iced it, ate a slice, and dumped the rest into the garbage.

This scene is resonant because it feels like such a waste to spend all that time creating a beautiful cake, only to dump most of it in the bin. Are the Wrysons perhaps only sampling a ‘slice’ of all life has to offer? Sure, they’re involved in the upzoning council hoo-ha, but as Cheever’s narrator explains, they are interested in nothing else. The cake is hidden from everyone, including Irene, though when she does finally see it, it’s an embarrassing, small, burnt thing not fit for consumption. She has discovered something about her husband that he didn’t want her to see, but in fact she hasn’t seen all those times he made a perfectly delicious and presentable cake. As far as she knows at the close of the story, her husband can’t bake. She has learnt only a tiny fraction of who he is, and is therefore baffled. She probably doesn’t connect that the smell of cake and maybe noises coming from the kitchen may be provoking her dreams of hydrogen bombs. Likewise, Irene does not tell Donald about her dreams.

“It’s a cake,” he said. “I burned it. What made you think it was the hydrogen bomb?”

SIDE-SHADOWING

This story contains an excellent example of this technique, which Cheever used previously in Just One More Time, and seems to have found it useful. Sideshadowing is a technique particularly well-suited to this tale full of different kinds of lacks and needs, because sideshadowing by definition describes what didn’t happen, but which might have. Note the phrases which turn this story into metafiction in which the reader, alongside the writer, is encouraged to consider the various ways in which this story might end:

GIVEN these unpleasant facts, then, about these not attractive people, we can dispatch them brightly enough, and who but Dolly would ever miss them? Donald Wryson, in his crusading zeal for upzoning, was out in all kinds of weather, and let’s say that one night, when he was returning from a referendum in an ice storm, his car skidded down Hill Street, struck the big elm at the corner, and was demolished. Finis. His poor widow, either through love or dependence, was inconsolable. Getting out of bed one morning, a month or so after the loss of her husband, she got her feet caught in the dust ruffle and fell and broke her hip. Weakened by a long convalescence, she contracted pneumonia and departed this life. This leaves us with Dolly to account for, and what a sad tale we can write for this little girl. During the months in which her parents’ will is in probate, she lives first on the charity and then on the forbearance of her neighbors. Finally, she is sent to live with her only relative, a cousin of her mother’s, who is a schoolteacher in Los Angeles. How many hundreds of nights will she cry herself to sleep in bewilderment and loneliness. How strange and cold the world will seem. There is little to remind her of her parents except at Christmas, when, forwarded from Shady Hill, will come Greetings from Mrs. Sallust Trevor, who has been living in Paris and does not know about the accident; Salutations from the Parkers, who live in Mexico and never did get their lists straight; Season’s Greetings from Meyers’ Drugstore; Merry Christmas from the Perry Browns; Santissimas from the Oak Tree Italian Restaurant; A Joyeux Noel from Dodie Smith. Year after year, it will be this little girl’s responsibility to throw into the wastebasket these cheerful holiday greetings that have followed her parents to and beyond the grave… But this did not happen, and if it had, it would have thrown no light on what we know.

The reader is brought back into the ‘real story’ with

What happened was this:

STORY SPECS IN “THE WRYSONS”

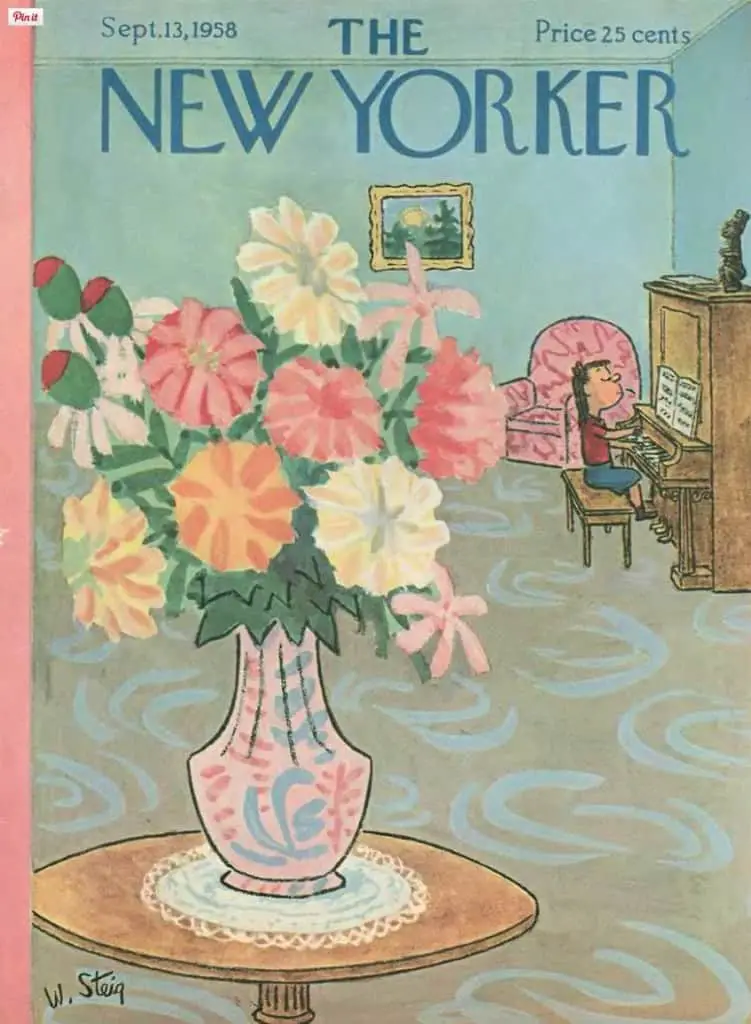

First appeared in The New Yorker in September 1958.

“The Wrysons” is one of Cheever’s shorter short stories, clocking in at only 2,600 words.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH “THE WRYSONS”

A short while before writing this story, Cheever wrote a kind of character sketch called “The Worm In The Apple”, which may be considered a preparatory story leading to The Wrysons, which has more of a plot. The most fleshed out ‘character’ in The Worm In The Apple is actually our unseen narrator, who is determined to see something rotten about a seemingly perfect all-American family that he imagines all sorts of horrible things about them. The narrator in that story has a more developed personality than most of Cheever’s third-person narrators, which are fairly bland and less biased, with a slightly pessimistic male sensibility.

WRITE YOUR OWN

A general rule in fiction seems to be: The more perfect-seeming the environment, the more rotten it will be underneath. This rot will be revealed to the reader, perhaps gradually, perhaps all at once, over the course of the story. The horror genre loves the suburbs, as do thrillers and psychological crime.

A short story, though, is likely to be successful if these extremes are dialled back a little, as Cheever has done here. If we’re not talking about murders, extra-marital affairs and illicit drug use in the suburbs, what might readers be left with which is perhaps even more interesting than any of those things, which we’ve seen many times and have come to expect? What are your characters most worried about? Can you shed some light on their psychological turmoil without changing their outward worlds very much at all?

In a story about lack, Cheever has described what isn’t there, made use of sideshadowing to show what didn’t happen and gave his characters a partial epiphany. In short, his narrative devices match his theme. What if your theme not about lack but about (over)abundance? What literary devices might you use then?