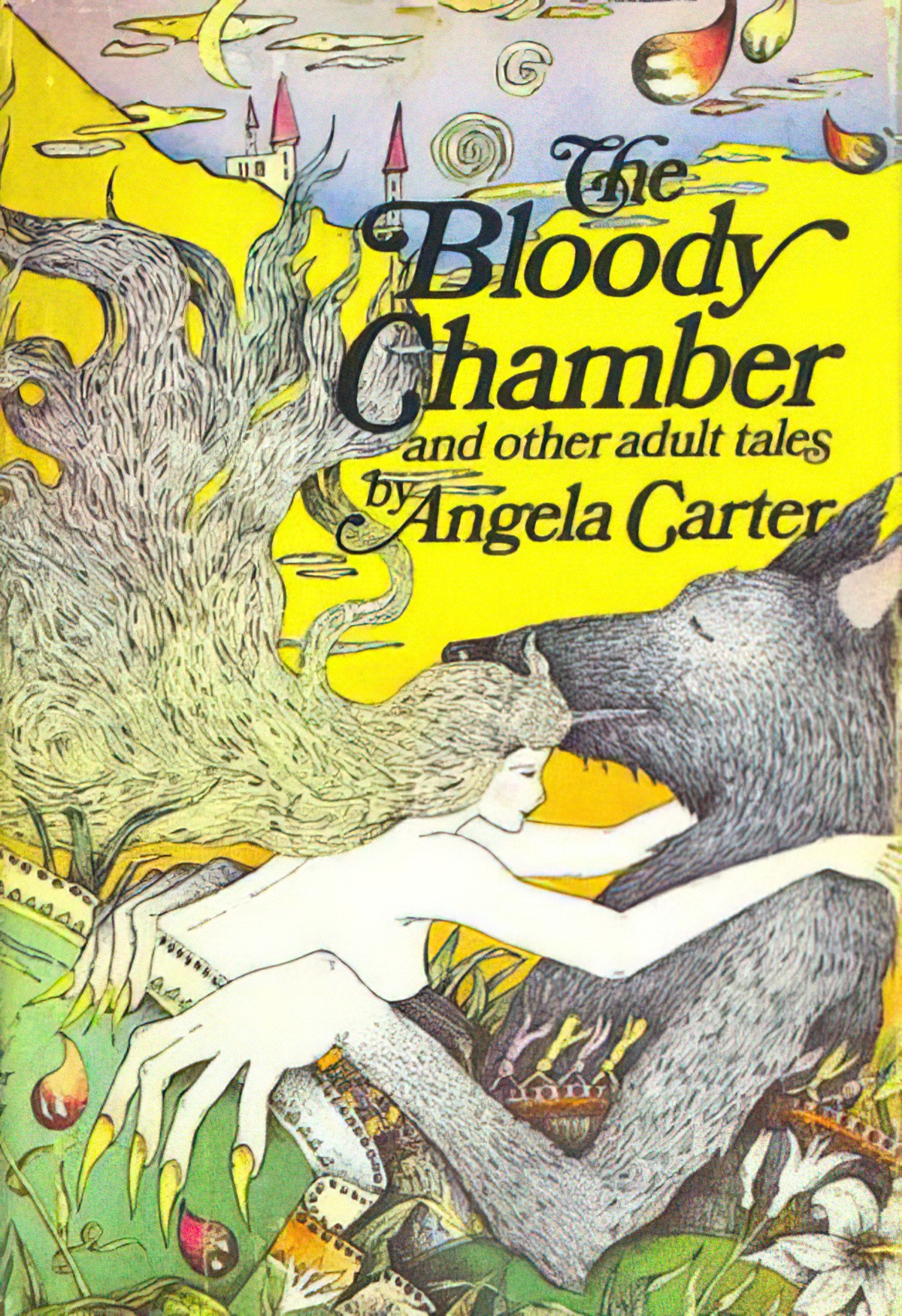

“The Tiger’s Bride” is a short story in Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber collection.

Marina Warner writes of stories in The Bloody Chamber, published during the post-war feminist movement which largely denounced fairytales and everything they stood for:

[Carter] refused to join in rejecting or denouncing fairy tales, but instead embraced the whole stigmatised genre, its stock characters and well-known plots, and with wonderful verve and invention, perverse grace and wicked fun, soaked them in a new fiery liquor that brought them leaping back to life.

PLOT OF THE TIGER’S BRIDE

In this inversion of Beauty and the Beast, Beauty ends up transformed into a fabulous Beast. Carter’s story is quite different from the original literary tale by French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, but readers will recognise it quickly because we still have Beauty, The Beast, the rose, the father who gives her away (gambles her away at cards) and the castle.

SETTING OF THE TIGER’S BRIDE

Having just moved from Petersburgh, Russia to a small, unnamed town in Italy, everyone who arrives must play a hand of cards with the grand seigneur (a great lord or nobleman — here, the Beast), though Beauty and her father’s Italian is not good enough to fully understand the repercussions of doing so.

PLACE – CLIMATE

Much is established early, in a single sentence:

There’s a special madness strikes travellers from the North when they reach the lovely land where the lemon trees grow.

There’s something about a story that opens in a bright, sunlit environment with bountiful food. We just know something bad is going to happen there. Happy family road trips which start with everyone singing along to the radio are a sure sign in horror films that all is not well.

PLACE – THE VILLAGE AND ABODE

This is a melancholy, introspective region; a sunless, featureless landscape, the sullen river sweating fog, the shorn, hunkering willows. And a cruel city; the sombre piazza, a place uniquely suited to public executions, under the heeding shadow of that malign barn of a church.

This story, along with the others in this collection, is set in traditional fairytale territory, in castles sans electricity, with forests and tundras and attics and dark basements:

The candles dropped hot, acrid gouts of wax on my bare shoulders.

The chill damp of this place creeps into the stones, into your bones, into the spongy pith of the lungs (milord’s castle is an oasis of chill even though the Italian climate is sunny – The treacherous South, where you think there is no winter but forget you take it with you.)

MAGICAL WORLD

This is an ancient world in which transmogrification is a thing. In our world, there are no magic mirrors, but when Beauty looks into a mirror she sees not her own face but the face of her father. When the Beast cries his tears turn into teardrop earrings.

CHARACTERS IN THE TIGER’S BRIDE

BEAUTY

Like the nubile protagonist in The Company Of Wolves, Beauty has agency and thinks for herself. She has since early childhood:

My English nurse once told me about a tiger-man she saw in London, when she was a little girl, to scare me into good behaviour, for I was a wild wee thing and she could not tame me into submission with a frown or the bribe of a spoonful of jam.

By the time Beauty is adolescent, she understands people and describes her father as ‘profligate’. Even for the times, this Italian village is 200 years behind. Beauty has chosen it because her father is a gambler and this place has no casino. So Beauty make the most of her own agency, thinking things through. She is certainly more than just beauty. There is nothing less satisfying in a story than good-looking female characters who make stupid decisions. (See many B-grade horror films for examples, the kind where you find yourself yelling, ‘Don’t go in there!’ at the screen.) Beauty acknowledges her own good looks but recognises them for what they are:

Since I could toddle, always the pretty one, with my glossy, nut-brown curls, my rosy cheeks…My mother did not blossom long; bartered for her dowry to such a feckless sprig of the Russian nobility that she soon died of his gaming, his whoring, his agonizing repentances. … For now my own skin was my sole capital in the world and today I’d make my first investment.

Unlike many traditional fairytale girls, she is not the epitome of feminine grace:

I let out a raucous guffaw; no young lady laughs like that! my old nurse used to remonstrate.

(Nor is she the ‘tomboy’ trope we see more recently in stories such as Brave, in which Merida is an expert markswoman.)

THE BEAST

The Beast (milord, the grand seigneur) has an unpleasant aroma about him:

My senses were increasingly troubled by the fuddling perfume of Milord, far too potent a reek of purplish civet at such close quarters in so small a room. He must bathe himself in scent, soak his shirts and underlinen in it; what can he smell of, that needs so much camouflage?

As in the original tale, the Beast is a recluse, shunned from polite society:

The Beast bought solitude, not luxury, with his money.

In his rarely disturbed privacy, The Beast wears a garment of Ottoman design, a loose, dull purple gown with gold embroidery round the neck that falls from his shoulders to conceal his feet.

The most terrifying aspect of the Beast’s description, for me, is the uncanny mask and wig:

only from a distance would you think The Beast not much different from any other man, although he wears a mask with a man’s face painted most beautifully on it. Oh, yes, a beautiful face; but one with too much formal symmetry of feature to be entirely human: one profile of his mask is the mirror image of the other, too perfect, uncanny. He wears a wig, too, false hair tied at the nape with a bow, a wig of the kind you see in old-fashioned portraits.

(See Uncanny Valley.) Creatures who look human, but not quite, are the most terrifying of all, and explains why humans have traditionally had more trouble developing empathy for apes than other fluffy creatures such as dogs and cats, who are very little like us. The automaton servants of this story are another version of uncanny.

…a strange, thin, quick little man who walked with an irregular, jolting rhythm upon splayed feet in curious, wedge-shaped shoes.

THEME IN THE TIGER’S BRIDE

BEAUTY DOES NOT EQUAL HAPPINESS

It’s interesting that the simulacrum maid resembles Beauty:

This clockwork twin of mine halted before me, her bowels churning out a settecento minuet, and offered me the bold carnation of her smile.

Note that the machine smiles even though Beauty cannot. And the maid offers Beauty her very own riding costume that she left back in Petersburg. What are we to make of this resemblance? That Beauty is not happy in her human form, perhaps. That she feels like a shell of a twin compared to the happy being she might be. The story points towards Beauty’s transformation being the thing that allows her to achieve happiness. This is all made clear eventually, with:

That clockwork girl who powdered my cheeks for me; had I not been allotted only the same kind of imitative life amongst men that the doll-maker had given her?

A GIRL ESTABLISHES INDEPENDENCE BY BREAKING AWAY FROM HER FATHER. VIRGINITY IS A BURDEN SINCE IT CAN BE BARTERED FOR A PRICE.

Significantly, Beauty is only asked to stand naked, but offers her lower half for penetration. (That he should want so little was the reason why I could not give it.) When she looks in the mirror (which may be magic or not) she sees the face of her father; she is channelling her father in order to get the transaction over with. But by the end of the story, her father has been forgotten. She is no longer under contract to be beautiful in order to get him out of debt; she has reclaimed her own baser instincts, turning literally into a beast.

I wished I’d rolled in the hay with every lad on my father’s farm, to disqualify myself from this humiliating bargain.

It becomes clear why Beauty feels so uncomfortable naked that penetration to her feels like a lesser thing:

I felt as much atrocious pain as if I was stripping off my own underpelt.

THE SIMULCRA AND OBJECTIFICATION

Apart from standing in as a lifeless version of Beauty, the maid simulacrum expresses thoughts about the sexual objectification of women:

…the smiling girl stood poised in the oblivion of her balked simulation of life, watching me peel down to the cold, white meat of contract and, if she did not see me, then so much more like the market place, where the eyes that watch you take no account of your existence.

And it seemed my entire life, since I had left the North, had passed under the indifferent gaze of eyes like hers.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE IN THE TIGER’S BRIDE

CONSTANT REFERENCE TO THE COLD

The Beast’s castle is a world in itself but a dead one, a burned-out planet.

The cold is important to this story, especially because Italy is not traditionally cold. Beauty and her father have ‘brought the cold with them’. In other words they have brought the unhappiness of their life in Russia with them, with the father unable to escape his gambling addiction in a village which insists newcomers gamble.

The first-time reader is unprepared for the inversion at the end, though on re-reading we’ll notice that Beauty is more at home with horses than people (and certainly more than ‘fake’ people):

I had always held a little towards Gulliver’s opinion, that horses are better than we are, and, that day, I would have been glad to depart with him to the kingdom of horses, if I’d been given the chance.

As the story draws to an end, the cold morphs slightly — still cold, there is brightness with it — a glimmer of hope:

Cold, that morning, yet dazzling with the sharp winter sunlight that wounds the retina.

FORESHADOWING, MAKING USE OF HORSES

She describes the horses in human terms:

An equine chorus of neighings and soft drummings of hooves broke out

Her own feet ‘clop‘ on the marble as she is lead up the stairs. This affinity for animals points to the likelihood of Beauty’s happiness as a she-Beast, with a half-man-half-beast who himself shares a dining room with horses. She describes the horses as ‘beasts in bondage’, as she herself is a daughter in bondage. The foreshadowing gets more and more obvious as the story progresses. Finally:

I always adored horses, noblest of creatures, such wounded sensitivity in their wise eyes, such rational restraint of energy at their high-strung hindquarters. I lirruped and hurrumphed to my shining black companion and he acknowledged my greeting with a kiss on the forehead from his soft lips.

She is, of course, about to kiss another kind of beast.

WORD USAGE

There are ancient turns of phrase scattered throughout the text:

My tear-beslobbered father

mutilated stumps of the willows flourished their ciliate heads athwart frozen ditches

‘Tantivy! tantivy! a-hunting we will go!’ (‘Tantivy’ is used as a hunting cry.)

Disturbing phrases:

The valet has the innocent cunning of an ancient baby – an excellent way of describing something uncanny, since ‘baby’ and ‘ancient’ don’t go together at all.

DETAIL

More than in many retellings of Beauty and the Beast, the reader is treated to a detailed description of the Beast, with details dripfed to us slowly. And sometimes we are offered animal symbolism indirectly, here through his chair:

The feet of the chair he sits in are handsomely clawed.

STORY SPECS OF THE TIGER’S BRIDE

Written in past-tense in first person point of view.

Found in the short story collection The Bloody Chamber published 1979

7700 words

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH THE TIGER’S BRIDE

Can you think of a popular modern children’s film that inverts a classic fairytale trope, with the Beauty ending up looking like the Beast?

I’m no fan of Shrek, though the gags are good when taken out of the context of story. Puss in Boots is great. But the message seems to be ‘Know your level’. Inversion is not subversion; in a subversion of the trope, the beautiful Fiona would have married the ugly Shrek, or better still, a handsome prince would have married (or lived in sin with) an ugly princess or pauper and they would have lived happily ever after despite their beauty differential. Instead, we’re told that we belong with people who are just as ugly/beautiful as we are. If they can’t both be beautiful, they must both become ugly. (This eclipses anything else about being ‘beautiful on the inside’, in my opinion.)

WRITE YOUR OWN SHORT STORY INSPIRED BY THE TIGER’S BRIDE

This is why it’s so hard to write a good modern fairytale. By simply inverting, are you really fixing anything up? What would true subversion look like in your favourite childhood tales?

RELATED

Fight clubs aren’t real, you aren’t in one. (The less flippant thing I have to say is that the horror of the human body is a deeply important and nearly inexhaustible topic for literature, but it is close to impossible to find a white, male, famous writer whose writing on this subject is anything but a thinly disguised demonstration of violent misogyny, and maybe you should read Angela Carter or Carmen Maria Machado instead.)

Electric Literature