“The Half-Skinned Steer” by Annie Proulx is, as said by Mary Lee Settle “as real as a pickup truck, as ominous as a fairy tale.”

Animals make an appearance in a lot of the story submissions we receive. Bunnies are maimed and killed. Dogs behave mischievously. Alligators threaten to attack. The truth is, many short story writers include animals in their tales, for different reasons. Many times, in our contests for emerging writers, an author will use a mangled or dead animal as a (seemingly) direct symbol for the loss of innocence, a dysfunctional family dynamic, or the end of a relationship. In other cases, the animal is not a direct symbol but merely a story element that interacts in a pleasing way with the rest of the narrative structure. Animals can add a level of tension or mystery to a story, they can drive the plot, or they can simply add texture. Though they can (often) be cute, animals are powerful presences in a story, and it’s interesting to consider the many different ways that they add to tales by contemporary writers.

The Masters Review

Contains spoilers, as usual.

“The Half-Skinned Steer” is the first short story in Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain collection published 1999. This particular story was published in The Atlantic in 1997 and the full text can be found in the archives.

Proulx understands story structure inside out and back to front, and approaches with an intent to parody, satirise, subvert or up-end. This story is a parody of your classic home-away-home story which I’ve written about elsewhere, due to my strong interest in children’s literature. (It’s particularly common in picturebooks). In this structure, a character — typically a man — leaves home, has an adventure, meets a bunch of opponents along the way, overcomes them, changes internally and either comes home or finds a new one. But in this story, our hero tries to come back home but gets killed just as he’s almost there. The events leading to this death are incremental and each quite minor, but like the film Fargo, in which William H. Macy’s character gets himself into deeper and deeper trouble, Mero’s demise manages to feel inevitable, surprising, tragic and funny all at once. Black comedy at its finest. Though I’d say there’s more black than there is comedy.

Words used to describe Proulx’s short stories

- truculent — aggressively defiant

- vernacular — “some of the horror in the stories is at times mitigated by the pregnancy and playfulness of the vernacular language of the characters and even sometimes of the omniscient narrative voices.” (I can’t remember where I got that quote from, sorry.)

- elliptic — here it is the adjectival form of ‘ellipsis’, this refers specifically to Proulx’s way of rendering dialogue and constructing sentences, by leaving bits out. (Nothing to do with being shaped like an ellipse.)

- understated

- deconstructionist — a way of constructing story which exposes contradictions and internal oppositions. A story can never be a complete thing in itself — it’s made up of parts which cannot be reconciled. There can’t be any neat, tidy ending. Also, there will be no single interpretation — takeaway points will depend on the reader.

- subversive — Proulx sets us up to expect one type of ending but we get another entirely, causing us to examine our own view of the world

- heteroglossic (the coexistence of distinct varieties within a single “language”)

- sharp-eyed attention to gritty detail

- stories take an irreverent stance

- minimalist — Americans use the term ‘minimalism’ whereas English scholars more often use the phrase ‘dirty realism‘ to describe the same thing. Dirty realism is on the realism spectrum (which also includes naturalism, social realism, magical realism, surrealism and metaphysical realism). If you don’t think Annie Proulx’s stories quite fit the term ‘magical realism’, you might use the word ‘minimalism’ or ‘dirty realism’ instead. Dirty realism is a term coined by the Granta magazine guy.

- lapidary (relating to the engraving, cutting, or polishing of stones and gems — here meaning ‘very carefully crafted’)

- wry in tone

- caustic, bitter

- ironic

- nouvelle-fabliau — a phrase coined by René Godenne to describe the defining traits of the early European short story. Proulx’s stories contain real-life anecdotes (she has said as much herself) which makes the stories feel very real.

- sinister

- grim, morbid, tragic

- Postmodern

- neo-regionalist (a late 20th century trend)

- Gothic backdrop

- blurred antinomy (between real life and the impossible — antinomy refers to ‘a real or apparent mutual incompatibility of two laws.’)

- plenty of parody, satire (sometimes ‘burlesque‘ is used to mean these things, though most people think of strip shows these days)

- metafictive (the author makes the reader consciously aware that they are reading a story)

SETTING

The realistic aspect of Proulx’s stories partly comes from extensive details giving a clear picture of the landscape, the climate, the ranches, houses and trailers, the clothes and food of her Wyoming characters. Their ranching, farming, rodeoing and other daily activities are also accounted for with much detail. Moreover, many of her stories are explicitly anchored in the history of the United States, and abound with references to background historical events and to real places.

[…]

Proulx’s overall somber universe abounds in predators, child abuse, rape, incest, zoophilia, and all sorts of imaginable forms of cruelty and deviance, but the monstrosities are sometimes held at a distance in at least some of the stories by their metafictional quality and the dry humor which brings a partial sense of comic relief.

Journal of the Short Story In English

When Close Range was published (the original title of the Brokeback Mountain collection), Proulx explained that the focus of both collections was on rural landscape, low population density and people who feel remote and isolated, cut off from the rest of the world, where accident and suicide rates are high and aggressive behaviour not uncommon.

In Proulx’s short stories, setting is so much a part of the story, the story couldn’t happen anywhere else. “The Half-skinned Steer” spans one man’s lifetime, with fluid time, jumping between the present as an old man and the past as a young one. Proulx even manages to imbue this story with the aura of timelessness by linking current, story events to an earlier era:

The anthropologist moved back and forth scrutinizing the stone gallery of red and black drawings: bison skulls, a line of mountain sheep, warriors carrying lances, a turkey stepping into a snare, a stick man upside-down dead and falling, red-ocher hands, violent figures with rakes on their heads that he said were feather headdresses, a great red bear dancing forward on its hind legs, concentric circles and crosses and latticework. He copied the drawings in his notebook, saying Rubba-dubba a few times.

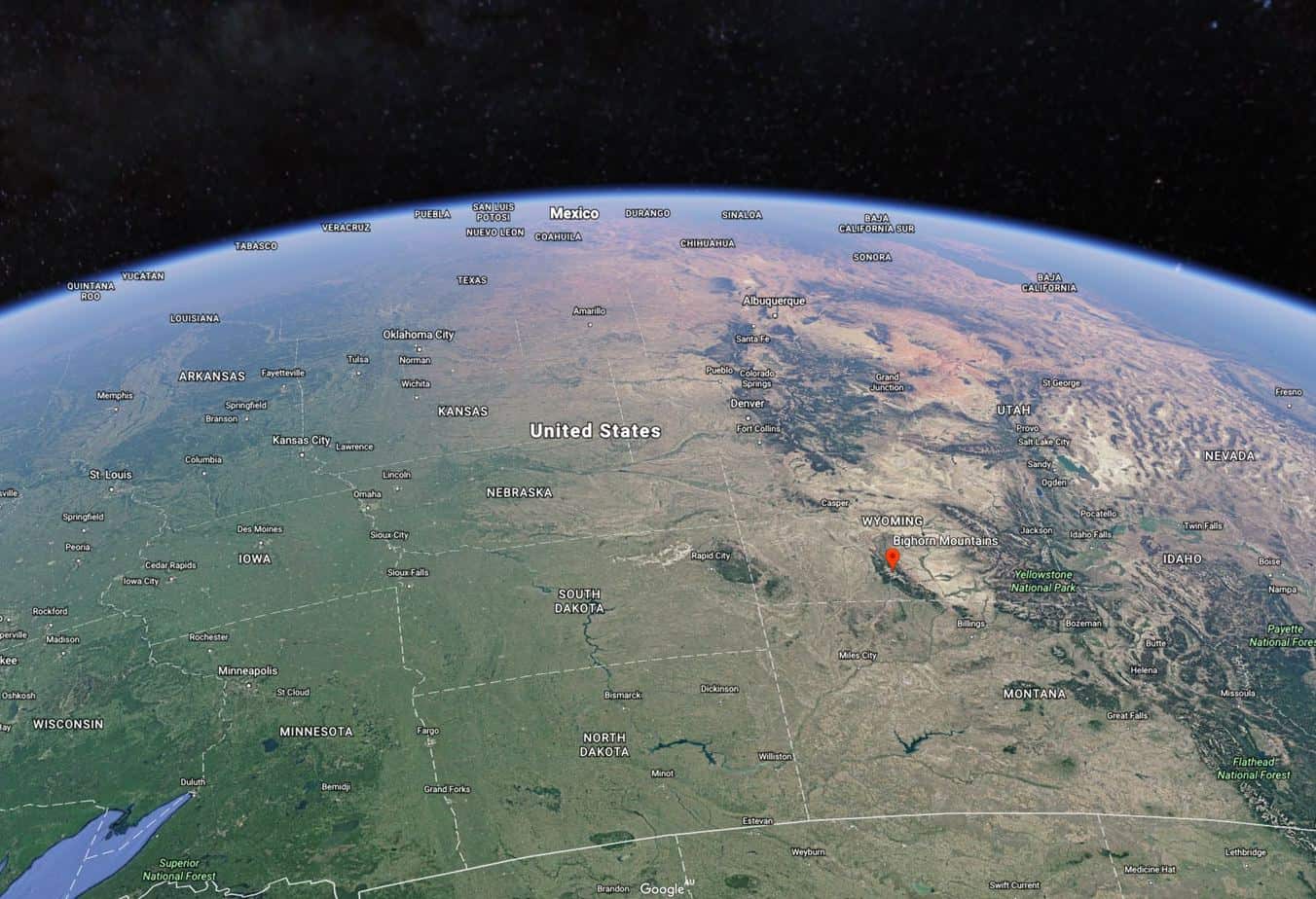

This is a rural setting in the foothills of the Big Horns (The Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming). The ‘south hinge’, to be more precise. I’m not entirely sure what is meant by ‘hinge’ when it comes to geology but it seems to refer to a bit of land which has been lifted and twisted via earthquake. (If you’re interested in the exact definition of a hinge when it comes to mountains, here’s a diagram and explanation.)

When you think Bighorn, think:

- High altitude and snowy

- Mule deer, elk, moose, black bears and mountain lions, pronghorn, herds of bison

- Roadless areas

- Little-known regions

- Steep canyons

- Hunters, fishermen and not many other people. But these days you’ll also find hikers, snowmobilers, backpackers and ultra-marathon runners.

- Semidesert prairie

- Douglas-fir

- Colorful rock formations

- Sacred areas belonging to the Crow Indian Reservation

- Three main highways going across it, designated as Scenic By-ways

- Rivers are called the Little Bighorn, Tongue and Powder

- A big national recreation area in the canyon, including Bighorn Lake (a reservoir dam)

- After Labor Day (4 September) you can encounter a high country snow storm at any time.

The place isn’t all that far from Yellowstone National Park, if you’ve ever seen a documentary set there.

Proulx describes the Bighorn region like this:

- “the old man said cows couldn’t be run in such tough country, where they fell off cliffs, disappeared into sinkholes, gave up large numbers of calves to marauding lions; where hay couldn’t grow but leafy spurge and Canada thistle throve, and the wind packed enough sand to scour windshields opaque.”

- A girl scout was killed by a lion.

- The ranch was bought by some rich businessman from Australia, who renamed it “Wyoming Down Under” — funny because this is such an American story. (I write this from Australia.)

- The scale of the mountains are described like this: “The country poured open on each side, reduced the Cadillac to a finger snap. Nothing had changed, not a Goddamn thing, the empty pale place and its roaring wind, the distant antelope as tiny as mice, landforms shaped true to the past.”

- Even the wind is brought to life as some sort of beast: “there was muscle in the wind rocking the heavy car, a great pulsing artery of the jet stream swooping down from the sky to touch the earth. Plumes of smoke rose hundreds of feet into the air, elegant fountains and twisting snow devils, shapes of veiled Arab women and ghost riders dissolving in white fume. The snow snakes writhing across the asphalt straightened into rods.”

- As Mero’s situation grows more dire, so do descriptions of the landscape: “The cliffs bulged into the sky, lions snarled, the river corkscrewed through a stone hole at a tremendous rate, and boulders cascaded from the heights.”

This story is kind of like an anti-Western (also called neo-Western) in that it’s about disenchantment with the Pioneer Spirit and the American Dream.

Annie Proulx’s sky is as geologically interesting as the ground:

The sky to the west hulked sullen; behind him were smears of tinselly orange shot through with blinding streaks. The thick rim of sun bulged against the horizon.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE HALF-SKINNED STEER”

Mythic Structure

This is basically a road trip, and road trip fiction is generally based upon the Odyssean mythic structure. You’ll also hear this kind of story referred to as a ‘(mythic) quest’. The reader is meant to look at both the outer journey and inner journey in order to garner meaning. Both threads are equally important. Mark Asquith makes note of the significance of Proulx’s point-of-view, which is mostly close third-person:

Mero’s journey is not simply geographical, it is also a psychological exploration of his reasons for leaving his father’s ranch some 60 years earlier. Indeed, for Fratz it is his move East that has allowed him to embrace the introspection and self-awareness that are alien to the anti-psychological stance of the mythic cowboy. Consequently, this is the most introspective of Proulx’s stories. Apart from Louise’s brief telephone call, we hear no other voice but that of Mero, who remains the focalizing agent throughout. This includes the powerful voice of the girlfriend, which is mediated through Mero.

The Lost Frontier: Reading Annie Proulx’s Wyoming Stories

The Half-Skinned Steer is also sometimes described as a ‘mock-epic’. What even is an epic? These days ‘epic’ seems to refer to anything massive, or in stories, a film which goes on and on and on (it probably has a massive budget). But ‘epic’ properly refers to a story in which the hero is the king and he is the founder of the city. Examples of epics run throughout history. Homer and Virgil in The Aeneid mark the beginnings of Greek nationalism. Then there’s the King Arthur legend where Arthur is the founder of the city of Camelot and the Round Table. That’s an epic. Mero can be considered a king returning to his kingdom, perhaps.

Intertextuality With The Myth Of Oedipus

Speaking of ancient stories:

It is suggested that Mero, sensing his and his brother’s desire for their father’s girlfriend, associates with the steer’s cruel treatment and develops castration anxiety–it is probably no coincidence that the bull from the original Icelandic tale has, in Proulx’s story, been traded for a steer, that is a castrated ox.

JSSE

I’m no fan of Freud or much of his psychoanalysis but the Urstory of Oedipus can be seen in lots of stories if you’re on the look-out for it.

Folk Tale Origins

A lot of Proulx’s Wyoming stories borrow from tall tales, local legends, folktales, fairy tales and myths, not just this one. The stories include grotesque freaks, monsters, hybrid creatures, devils and demons. Here we have the horror trope of the villain who you just can’t kill, except the steer isn’t a villain. In which case, isn’t it the human who is the villain?

“The Half-Skinned Steer,” which was first published in The Atlantic Monthly, is based on an old Icelandic folktale, “Porgeir’s Bull.”

Annie Proulx, acknowledgements

If you look for that tale on the Internet (in English) you’ll find that most of the top entries are in reference to Proulx’s story rather than the original. Proulx has brought it to our consciousness.

Supernatural bulls have a long tradition though, not just in that Icelandic tale. You’ll even find one in The Epic of Gilgamesh.

On the Epic of Gilgamesh: A Discussion with Stanley Lombardo

Stanley Lombardo is Emeritus Professor of Classics, University of Kansas. His previous translations include Homer’s Iliad (1997, Hackett) and Odyssey (2000, Hackett), Hesiod’s Works & Days and Theogony (1993, Hackett), among others.

New Books Network

In the Icelandic tale, from what I can gather, this wizard called Porgeir skins a calf in such a way that the hide remains attached only at the tail. Ghosts ride the monster’s bloody sled from one end of a river to the other. (I’m not sure what happens after that, or what the point is.)

Story Within A Story

“The Half-Skinned Steer” is a beautifully integrated example of a ‘framing story’. The fancy word for this is mise-en-abîme.

…the embedded narrative structure serves as a way to cast light on the tall-tale aspect of the story which is told by Mero’s father’s girlfriend, allegedly a true story which has happened to one of the locals: certain that he has killed a steer intended for food, the grotesque character named Tin Head.

JSSE

The story-within-the-story starts with:

The girlfriend started a story, Yeah, there was this guy named Tin Head down around Dubois when my dad was a kid.

Then there is a flash forward, back to the present and we get more of the story starting with:

Well, well, she said, tossing her braids back, every year Tin Head butchers one of his steers, and that’s what they’d eat all winter long, boiled, fried, smoked, fricasseed, burned, and raw.

Except the thing is, we’re not told the story. We’re told Mero’s reaction to it:

Mero had thrashed all that ancient night, dreamed of horse breeding or hoarse breathing, whether the act of sex or bloody, cutthroat gasps he didn’t know. The next morning he woke up drenched in stinking sweat, looked at the ceiling, and said aloud, It could go on like this for some time.

Part three comes at the point we rest assured Mero is going to make it back to the ranch:

Winking at Rollo, the girlfriend had said, Yes, she had said, Yes, sir, Tin Head eats half his dinner and then he has to take a little nap.

Part four after he gets lodged on the rocks:

My Lord, she continued, Tin Head is just startled to pieces when he don’t see that steer. He thinks somebody, some neighbor, don’t like him, plenty of them, come and stole it.

This has the effect of bringing the steer into the present landscape. We imagine Mero looking through the snow and actually seeing the steer.

Note that the story-within-the-story is not a complete story. When Rollo responds with, “That’s it?” in a ‘greedy, hot way’, he’s noticed that there has been no big struggle between the steer and Tin Head, no indication of a new situation. That’s what the ‘wrapper’ story is for — the main story, of Mero’s demise, will give us the conclusion the father’s girl-friend’s story doesn’t.

Shaggy Dog Tales

There’s a category of tall stories which have abrupt endings. The teller takes delight in building up, building up, then leaving the listener (reader) hanging. They’re known as ‘Shaggy Dog Stories’. While the girlfriend’s story isn’t exactly that, she seems to take great delight in grossing Mero out, and this is the entire point of the story.

I’ve seen it in children’s stories, too. Here’s an example from Polish-German storyteller Janosch:

In traditional (Australian) tall stories, the fun comes from getting the listener to believe in ridiculous stories. In these stories with the abrupt endings the ‘fun’ comes from leading someone to believe that one outcome is coming up but defying expectations at the last minute.

Anything can end abruptly, whether it’s a scene or a sentence, but the ending of a story is the most significant ‘outcome’ and so has the most impact when it’s cut off.

SHORTCOMING

Mero wound up sixty years later as an octogenarian vegetarian widower pumping an Exercycle in the living room of a colonial house in Woolfoot, Massachusetts.

83-year-old Mero Corn is a reluctant, tragic hero. He thinks his life is about over when he gets a call from Wyoming, where he grew up, to say come back and maybe run the emu farm — also your younger brother has died. He’s scared of flying so drives his Cadillac from Massachussets. (I don’t think Woolfoot is a real place but the name of it suggests another rural setting, somehow.)

We can see from the description of Mero that he is careful about his health. He is the prepared type. That’s what makes this story all the more tragic and ironic. How does a man get stuck in his situation?

Note that the elderly Mero is vegetarian. I didn’t notice the significance of this first mention the first time I read it, but as soon as you go back you realise the exact moment he stopped eating meat, and it wasn’t anything as melodramatic as hearing the story about the half-skinned steer and then swearing off it for life. That moment happened later, recalled in this memory:

He crossed the state line, hit Cheyenne for the second time in sixty years. He saw neon, traffic, and concrete, but he knew the place, a railroad town that had been up and down. That other time he had been painfully hungry, had gone into the restaurant in the Union Pacific station although he was not used to restaurants, and had ordered a steak. When the woman brought it and he cut into the meat, the blood spread across the white plate and he couldn’t help it, he saw the beast, mouth agape in mute bawling, saw the comic aspects of his revulsion as well, a cattleman gone wrong.

Mark Asquith describes Mero’s psychological shortcomings in more words than Annie Proulx ever uses, which is testament to the compression that can be achieved by a masterful short story writer:

Mero Corn is a victim of his own delusions. When we meet him at the beginning of the story he is a confident easterner: a vegetarian who keeps fit on an Exercycle and makes his money from boilers, air duct cleaning and smart investments. When he gets the call summoning him to his brother’s funeral, he resolves to drive; despite his age, the distance, and the winter season, he believes that Wyoming holds no surprises for a man brought up in the West but grown successful in the East. His Cadillac, which e replaces at whim (‘he could do that if he liked, by cars like packs of cigarettes’ is a symbol of his success, but it is, as he will find to his cost, useless in Wyoming’s harsh landscape. His confidence is also signalled by his belief that the map of Wyoming that he carries in his head still matches the actual geography. As he crosses the state line he exultantly observes: ‘Nothing had changed, not a goddamn thing, the empty pale place and its roaring wind, the distant antelope as tiny as mice, landforms shaped true to the past.’ It is a landscape of the imagination rather than reality: the wildlife seems to have emerged from a child’s toy box while the ‘landforms shaped true to the past’ evoke a nostalgic link to glacial carving and careful agricultural husbandry rather than mineral extraction. Because everything has changed: ranches that were once flourishing — like the deserted Farrier place — have fallen apart, and the ranch to which he is returning has become an Australian themed ranch — “Down Under Wyoming.”

The Lost Frontier: Reading Annie Proulx’s Wyoming Stories

But the entire story is from Mero’s point of view, we are encouraged to identify with Mero, and so if this story is saying anything at all about humankind that means Annie Proulx is saying something about people in general. What is she saying?

Through the introduction of this comical ranch, Proulx is making a serious point concerning the degree to which all landscapes are a product of cultural expectation. Just as Mero’s construction of the landscape is predicated on a combination of boy hood memory and the myth of the West, our own conception of the authentic West is built on a belief in the ‘naturalness’ of the cattle ranch. Through her introduction of an exotic species, Proulx is remind us, as Milane Duncan Frantz has observed, that cattle are just as artificial as emus in the West; the absurdity of the latter simply fits outside our imaginative geography. Furthermore, Proulx is also using the emu to interrogate the nation of ‘wild’ and ‘domesticated’ when attached to certain animal breeds, and by extension the whole landscape. This confusion proves fatal to Rollo, who is clawed to death by an emu because he fails to recognize the wild creature beneath the absurd animal of his own advertising. His gory death not only summons his brother, but foreshadows Mero’s own tragedy. This comes when his carefully constructed memory of the West (a domesticated vision transformed into postcard kitsch) comes into contact with the storm-ridden reality.

The Lost Frontier: Reading Annie Proulx’s Wyoming Stories

Then there is Mero’s problem with women:

Although he congratulations himself on his sexual prowess…his departure was hastened by sexual confusion heightened by the girlfriend’s story. It is a bewilderment that can be traced back to his early childhood where it emerges from a confused understanding of his landscape. When a visiting anthropologist shows him some Native American stone carvings of female genitalia, he mistakes them for horseshoes. As a result of his embarrassment, not only does Mero subsequently confuse the homophones ‘cymbal’ and ‘symbol’ (leading to some strange connection between sex and marching bands), but also from this point on ‘no fleshy examples ever conquered his belief in the subterranean stony structure of female genitalia.’ Thus, from his earliest age, sex is associated with both horses and the cold, dark and mysterious.

Later, taking his cue from the ranch around him, this confused belief develops into the idea that the sexualised woman is animalistic, exemplified by his father’s girlfriend, who he continually associates with a horse: ‘If you admired horses you’d go with her for her arched neck and horsey buttocks, so high and haunch you’d want to clap her on the rear’. She exists only in Mero’s memory, and remains anonymous because she only gains significance in relation to the father and is only understood by patriarchal definitions of what is wild and erotic. After she tells the story of ‘The Half-Skinned Steer’ he dreams ‘of horse breeding or hoarse breathing, whether the act of sex or bloody, cut-throat gasps he didn’t know’. Sex, horses and cattle slaughter now become inextricably intertwined in his imagination and as he begins to suspect a growing relationship between her and Rollo, he increasingly identifies himself with the steer. The full significance of Proulx’s transformation of the bull of the original Icelandic tale to a steer (a castrated bull) becomes a symbol of Mero’s castration complex.

The Lost Frontier: Reading Annie Proulx’s Wyoming Stories

In short, this man was really mucked up when that anthropologist took him into the cave and showed him the etchings of the vulvas.

DESIRE

Mero is happy enough on his treadmill in Massachussets but after the phone call (The Call To Adventure) he wants to travel back to the ranch where he grew up, attend his brother’s funeral and perhaps find something to do with the rest of his years.

Maybe, he thought, things hadn’t finished turning out.

Proulx has an innovative way of describing this Call To Adventure:

He would see his brother dropped in a red Wyoming hole. That event could jerk him back; the dazzled rope of lightning against the cloud is not the downward bolt but the compelled upstroke through the heated ether.

OPPONENT

Natural opponent: The hostile weather — the snow, the bush which blocked the entrance, the rocky terrain which demobilised his Cadillac.

The Circumstances: Daniel Handler makes overt use of this in A Series of Unfortunate Events, which could describe many stories of this type. When the original Cadillac breaks down this is fatal, since all the survival equipment has been left inside it.

Self as opponent: The memory of the steer, or maybe the steer itself depending on your reading of the story. The memory of the half-skinned steer plagues him the closer he gets to his home ranch and when calamity befalls him, Mero almost feels he’s paying penance by succumbing to the cold.

Human opponent: The old man’s girlfriend is both the love opponent (he can’t have her, doesn’t really want her), and also managed to really disturb him by telling him the story in the first place. She is portrayed as a bit of a witch, though the truth is she’s just a very good storyteller:

It was her voice that drew you in, that low, twangy voice, wouldn’t matter if she was saying the alphabet, what you heard was the rustle of hay. She could make you smell the smoke from an imagined fire.

Louise, Tick’s wife isn’t exactly helpful (though Tick is even less so, refusing to make the call his own damn self). She tries to be helpful by offering to pick him up from the airport but when it comes to guiding him to the ranch by vehicle she’s set him up for failure. Louise is a completely unwitting opponent.

PLAN

Things go wrong and plans change. We’re on Mero’s side because he is cool-headed. He’s a good travel companion in that respect.

When he meets with a car accident he simply buys a new Cadillac.

When he can’t find the entrance to the ranch he simply drives slowly until he finds an entrance.

When he gets lodged upon rocks he simply uses the last half-tank of petrol to keep warm.

He will knock on the door of an old neighbour in the morning. This plan has a strong emotional impact on me, reminding me of the sadness of getting very old, realising that most people you’ve known are dead:

I’ll be cold but I won’t freeze to death. It played like a joke the way he imagined it, with Bob Banner opening the door and saying, Why, it’s Mero, come on in and have some java and a hot biscuit, before he remembered that Bob Banner would have to be 120 years old to fill that role.

BIG STRUGGLE

And so on, until he’s got nothing left.

ANAGNORISIS

In a short story it’s often the reader who has the revelation, about the character and ultimately about ourselves or about the human condition. If Mero has a revelation it’s that he’s not worthy of living after failing to kill that steer mercifully way back when.

Mero, the seer rather than the steer, eventually becomes aware, “in the howling, wintry light,” of the everlasting power the symbol of the half-skinned steer has held upon him, and what it stands for, despite his vain attempt to run away from his buried, unconscious psyche.

JSSE

The reader is reminded that nature will win out in the end.

NEW SITUATION

When the point-of-view pans out we know to approach the scene as detectives who have arrived after the scene of a tragedy:

On the main road his tire tracks showed as a faint pattern in the pearly apricot light from the risen moon, winking behind roiling clouds of snow.

He’s not dead yet, though. The tangles of willow are described as ‘bunched like dead hair’ — rather than telling us Mero has died, she gives us all the hints in the world via death imagery in the landscape.

We may extrapolate that Tick and his partner won’t stay at the ranch either, and the land will return to its natural state, having shrugged off its human inhabitants.

Or perhaps you didn’t read it like this at all? Perhaps Mero gets to the funeral after all. As Nancy Kress points out, short stories don’t have to show us any new situation. (She calls this a denouement):

In a short story there may or may not be a denouement. In some stories—especially those that are very short—the climactic moment, in which the protagonist undergoes a change, may also be the last moment of the story. What happens to her after that is left to the reader’s imagination. In other stories, the denouement may consist of a sentence, a paragraph, or a brief scene clarifying what happens to the character after she changes.

Nancy Kress, from Beginnings, Middles and Ends

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE IN “THE HALF-SKINNED STEER”

This paragraph demonstrates two notable techniques:

He said he would be at the funeral. No point talking about flights and meeting him at the airport. He intended to drive. Of course he knew how far it was. He had a damn fine car, never had an accident in his life, knock on wood

First we have the one-sided conversation. There’s no need to write out the whole thing — we know what the other party has said: “Are you sure you’re going to drive? We can meet you at the airport. Do you know how far it is?”

We also have foreshadowing of bad stuff to come with the ‘knock on wood’. Readers familiar with the author will already be expecting something terrible, but no writer can rely on just that. In real life jinxes aren’t a thing, but that isn’t true in fiction. ‘Never had an accident in his life’ means he’s going to have an accident, probably.

Even the Cadillac is described as if it’s an animal dripping blood:

he watched his crumpled car, pouring dark fluids onto the highway

The next night he personifies the old ranch house in his dream:

Below the disintegrating floors he saw galvanized tubs filled with dark, coagulated fluid.

Adjectives In “The Half-Skinned Steer”

…figuring he must be dotting around on a cane, too, drooling the tiny days away — she was probably touching her own faded hair. He flexed his muscular arms, bent his knees, thought he could dodge an emu. He would see his brother dropped in a red Wyoming hole.

Plenty of people in writing groups will try and persuade you that adjectives are evil and should be slashed left, right and centre, but I am pro-adjective and I like it when excellent writers back me up on this point by using them well. First point: You can only get away with adjectives when the verbs are also strong. Second point: At least some of your adjectives have to be surprising and just plain ‘apt’. ‘Tiny days’ describes perfectly the way the old man’s life had shrunk in old age, but in a wonderfully succinct way. ‘Muscular’ arms isn’t clever as such — just descriptive, and that’s fine too. A ‘red Wyoming hole’ describes the colour of the dirt, I guess. For Americans I bet the colour red is reminiscent of other things too, like conservative politics. (It’s opposite here, Down Under — blue is conservative, red is more liberal.)

Later in the story, after his car accident, Mero drinks ‘a cup of yellow coffee’. Although it’s such a simple adjective, it made me stop and wonder how on earth coffee could be yellow. (Paleo-recipes with turmeric aside.) I figure it must be how he’s seeing the world now — increasingly as an old man. Because of the Kodak corporation and their defective film, we as readers have been associating the colour yellow with age since the 1970s. (Though I’m sure it’s not just down to Kodak — white linens and papers also yellow with age.)

Magical Realism in “The Half-Skinned Steer”

Most people studying the work of Annie Proulx focus on the following areas:

- naturalism (extreme realism which emphasises the role of family background, social conditions and environment in shaping human character)

- postmodernism (characterized by reliance on narrative techniques such as fragmentation, paradox, and the unreliable narrator)

- neo-regionalism (regionalism sets up a conflict between city and rural areas; neo-regionalism expands right out and is a response to globalisation.)

But I believe this story is a very good example of magical realism.

Here’s one definition of the technique:

Magical realism is a technique in which a plausible narrative enters the realm of fantasy without establishing a clearly defined line between the possible and impossible.

I think of magical realism as like (very) low fantasy but without a portal. Plain old fantasy not only makes use of some sort of portal, but generally lingers in that space for a while to allow the reader sufficient time to mentally leap from reality to unreality.

But is that what this story is? You might read the vengeful steer as purely hallucinatory, in which case is it magical realism at all? When trying to work out if it’s an hallucination, take a close look at the degree of ‘internal focalisation’. How far back does the point-of-view ‘camera’ pull away? The more omniscient the narrator, the less we should regard something in the text as if it’s an hallucination. Another possibility: We’re already had hints of dementia. Mero couldn’t remember where he was going when the pimply cop pulled him over. Could it be that?

If you look up ‘magical realism’ you won’t find Annie Proulx listed as one of the big shakers in this area, but like New Zealand’s Keri Hulme, she probably actually is.

Annie Proulx certainly makes use of some other magical symbols in her hyper-realist stories. Here we have reference to a full-moon, commonly used to indicate some sort of magic:

He was half an hour past Kearney, Nebraska, when the full moon rose, an absurd visage balanced in his rearview mirror

So that’s one argument in favour of the magical reading. On the other hand, Mero is cold, thirsty and disorientated to the point where he breaks into his car which isn’t even locked.

Allegorical Names In “The Half-Skinned Steer”

It has been pointed out that Mero might be an anagram for “more.”

In addition, Mero stands as a near-palindrome for Homer, and, finally as a truncated version of Oedipus’ adoptive mother’s name, Merope. (And if you’re into Freudian psychoanalysis, Sophocles offers the Urtext when it comes to sons and their displaced erotic feelings for their mothers.)

Make of that what you will, but Annie Proulx does not choose run-of-the-mill names for her characters.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST “THE RED-SKINNED STEER”

James Agee’s “A Mother’s Tale” — set on a ranch, a cow narrator

Flannery O’Connor’s “Greenleaf” — another tragic tale including a bull. (Many of Proulx’s anti-heroes read as grotesque figures reminiscent of the Southern freak tradition inherited from Flannery O’Connor.)

Work by Sherwood Anderson. O. Alan Weltzien has called Proulx’s Wyoming grotesques “weathered, Western descendants of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg Ohio gallery.”