In his story ‘The Cure’, Cheever comes pretty close to writing a supernatural thriller story, with a few typical thriller genre beats. The stars are ordinary heroes, or to use Northrop Frye’s terms, mimetic heroes. Compared to detective stories there are fewer suspects in thriller stories (though the word ‘thriller‘ is used by Hollywood to mean anything that gets the heart racing).

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE CURE”

From The New Yorker:

The story of a man’s attempt to cure himself of a disastrous marriage. His wife, Rachel, had left him for the 2nd time taking their three children with her. He had set up a routine for himself and wouldn’t answer the telephone, for he wanted no reconciliation with Rachel. But he was unnerved by a peeping Tom, who appeared at the window every night. When he discovered it was a neighbor who was harmless he felt no better. He seemed to see a rope around his own neck and he couldn’t sleep. Finally he answered the telephone. It was Rachel and a reconciliation followed. Tom was never seen again and all was well.

The New Yorker refuses to spoil the real story — theirs is a surface level summary, avoiding spoilers. The interesting question is: How much of this story is true, within the world of the story?

SETTING OF “THE CURE”

Place

Critics like to divide Cheever’s stories into:

- Suburban stories

- New York stories

- Holiday stories

But “The Cure” fits into none of those categories. It is about a man crossing the boundaries between New York, where he works, and the suburbs, where he lives. Some critics call this an ‘exurban’ story.

I was in a neighborhood where most of the front doors were unlocked, and on a street that is very quiet on a summer night. All the animals are domesticated, and the only night birds that I’ve ever heard are some owls way down by the railroad track. So it was very quiet.

This is also a story about a man who crosses a different kind of border: Not only between urban and suburban life, but between day-life and night-life, and sanity to madness.

Time

It is the early 1950s when this story is published, though the narrator is writing of events long ago. He is reminded of the Depression at one point, so this story probably takes place sometime between about 1930 and 1950.

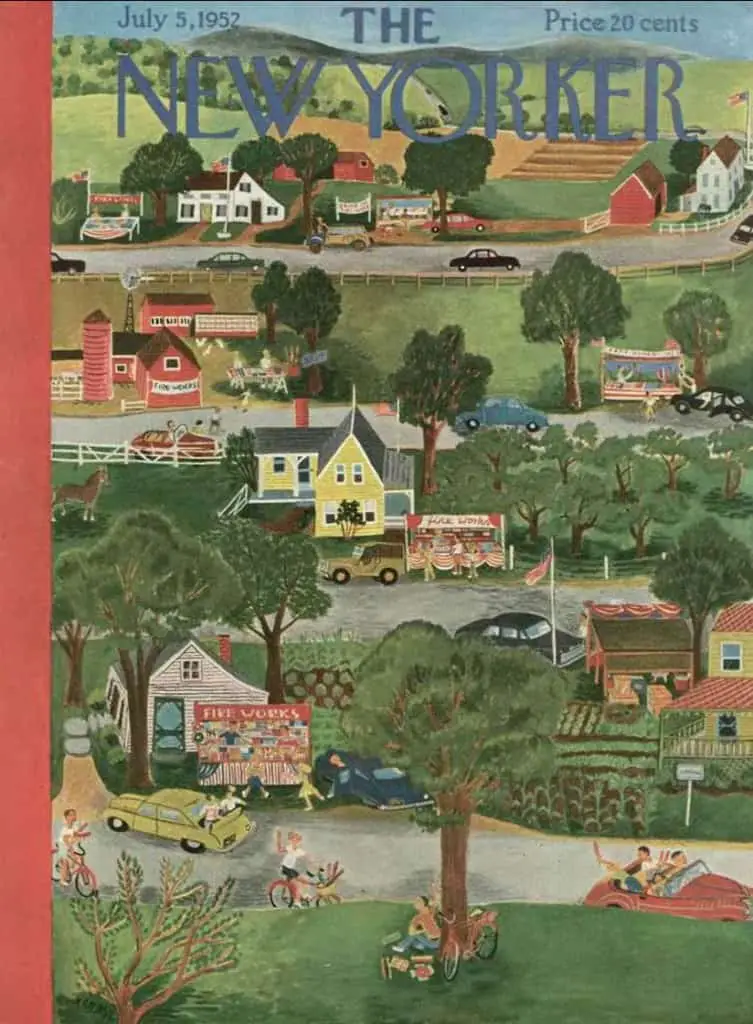

More than in other Cheever stories, the season is emphasised in this story as if symbolically significant. It is a very summery story — the reader feels the heat, and hears the sounds and smells the smells of the season. Is the season important to the story? Yes, in the sense that it allows for more outdoor living and longer evenings. Just as importantly, The New Yorker published this story in July, at the height of the Northern Hemisphere summer, and probably wanted to publish something seasonally appropriate.

THIS HAPPENED in the summer. I remember that the weather was very hot, both in New York and in the suburb where we live. […] I was glad that the separation took place in the summer because my job is most exacting at that time of year and I’m usually too tired to think of anything else at night, and because I’d noticed that summer was for me the easiest season of the year to live through alone.

Of equal significance: This turns into a story of ‘the night’. The narrator goes from being a day person to a night person.

I had never had anything to do with night people, but I know that they exist […] I was very sleepy the next day, but I got my work done and dozed on the train coming home. […] The sky and the light and everything else seemed dim and remote, as if I saw it all from a great distance. […] It was about two o’clock on a sunny afternoon but it seemed dark to me.

The night becomes a symbol for his descent into darkness/depression/madness. Notice how many times in the following paragraph Cheever uses the phrase ‘I lay in the dark’:

It was after four then, and I lay in the dark, listening to the rain and to the morning trains coming through. They come from Buffalo and Chicago and the Far West, through Albany and down along the river in the early morning, and at one time or another I’ve traveled on most of them, and I lay in the dark thinking about the polar air in the Pullman cars and the smell of nightclothes and the taste of dining-car water and the way it feels to end a day in Cleveland or Chicago and begin another in New York, particularly after you’ve been away for a couple of years, and particularly in the summer. I lay in the dark imagining the dark cars in the rain, and the tables set for breakfast, and the smells.

As I read through the first time, I expected this story to end in suicide. We are encouraged into this reading, first with the obvious clue, then with the narrator’s slightly later realization:

I remember that I took a bath and put on pajamas and lay down. As soon as I shut my eyes, I saw this rope. It had a hangman’s noose at the end of it, but I’d known all along what Grace Harris had been talking about; she’d had a premonition that I would hang myself. The rope seemed to come down slowly into my consciousness.

As readers we’re trained to suspend disbelief when it comes to old women who can predict the future, even if we wouldn’t accept such supernatural stuff in real life. So when Grace Harris tells the narrator that she sees a rope around his neck, I am led to believe his descent will end in suicide. (Much like Mad Men, in fact, which apparently owes a lot to Cheever.) In other words, this is a form of foreshadowing. Why is he cashing a check for such a large amount? Why is he buying a suit?

I went to the Corn Exchange Bank and cashed a check for five hundred dollars. Then I went to Brooks Brothers and bought some neckties and a box of cigars and went upstairs to look at suits.

Milieu

This is the New York where other people’s children are tangentially suffering from polio. When divorce was a rare and terrible thing. Polio has nothing to do with the plot, but is mentioned, perhaps as a way to place the story in time. Since men don’t cook they must eat steak at a bar if they’re to eat at all. The starkly gendered division of labour means a stable marriage is even more vital to one’s well-being. Instead of watching TV or surfing the net, evenings are spent at the drive-in theatre. Men are drinking martinis in the evenings. Readers might have been enjoying the work of Lin Yutang, as Rachel had done. Lin Yutang is best known for his book The Importance of Living, and I’m guessing this is the book the narrator is meant to have picked up when he couldn’t sleep.

CHARACTERS IN “THE CURE”

The Unnamed Narrator

Why is this narrator unnamed? (Must there be a reason?) If there’s a reason, it’s probably because this man has lost himself. Without his wife and family he is no one, descending slowly into a kind of madness.

The vast majority of Cheever’s stories are written in the third person, but this one is told by a character as narrator. Since this is not Cheever’s modus operandi, we might naturally ask: To what extent is this narrator reliable?

The final sentence turns this short story into a kind of newsy letter, as if to an extended family member:

Mr. Marston has never stood outside our house in the dark, although I’ve seen him often enough on the station platform and at the country club. His daughter Lydia is going to be married next month, and his sallow wife was recently cited by one of the national charities for her good works. Everyone here is well.

His psychological shortcoming is that he is lonely. His moral shortcoming is that he is paranoid, blaming a neighbour for peeping at him through the window with little in the way of evidence. On the other hand, he shows he is capable of compassion when it suits him:

I guessed that he was probably some cracked old man from the row of shanties by the railroad tracks, and perhaps because of my determination, my need, to put a pleasant, or at least a calm, face on everything, I even managed to think compassionately of the old man who was driven, in senescence, to leave his home and wander at night in a strange neighborhood, at the mercy of dogs and policemen […] I thought of the poor prowler and his long walk home through the storm.

Peeping Tom

Though the New Yorker snippet summarises the surface level goings-on in this story, if you read it, it’s unclear as to whether Peeping Tom even exists, or if the narrator is imagining a face at the window, then telling himself it is the face of one of his neighbours. Perhaps he’s seeing his very own face? There is a phenomenon called “mirrored-self misidentification“. Basically, it’s when you look into the mirror and you don’t recognise yourself. You actually think it’s another person. In children’s literature, New Zealand author touches on this phenomenon in her young adult novel The Changeover. Although this delusion is associated with head injury, dementia and mental illnesses, I do think most people can identify with it to some degree. Don’t all of us have a moment where we look into the mirror and we look much older than we feel? Or more tired, or perhaps we’re struck by how good looking we are? Or we catch ourselves at a different angle and realise our nose looks different from how we imagined. Looking at oneself for the first time in one of those three-way mirrors can have a similar effect.

The following writer interprets Tom as an hallucination, as I do:

In “The Cure” we see Rachel already separated from her husband. Twice before they had separated and the second time they had divorced and remarried. Her husband, though agreeing that it was a “carnal and disastrous marriage” is unable to bear loneliness. It starts pulling on him, giving him hallucinations, he even imagines a peeping Tom at nights whom he cannot shoo away. The only cure seems to be to get Rachel back — the errant on the right track. But in “The Country Husband” the protagonist goes off at a tangent since he is unable to communicate properly. He meets death very closely as his plane crashes. He wants to narrate this first to his neighbours then to his wife and children who are all unable to register his extraordinary experience.

from Uncovering Greyness In John Cheever’s Stories

Certainly we are given enough evidence that the narrator is not of entirely sound mind.

Tom didn’t appear-or I wasn’t conscious of him-until they had been gone for about two weeks, but her departure and his arrival seemed connected.

While cats are known to wander, I’m suspicious about the dog — did the pets leave out of neglect?

There were a few minor symptoms of domestic disorder. First the dog and then the cat ran away.

Perhaps sleeplessness is contributing to the narrator’s unsound mind:

But I don’t sleep very well in an empty bed, and presently I had the problem of sleeplessness to cope with. When I got home from the movies, I would fall asleep, but only for a couple of hours. I tried to make the best of insomnia.

Is it really possible to know you’re being stared at?

without lifting my eyes from the book, I knew not only that I was being watched but that I was being watched from the picture window at the end of the living room, by someone whose intent was to watch me and to violate my privacy.

The narrator may have trampled on his own flower bed the previous night while looking for the ‘mysterious footstepper’:

There is a flower bed under the narrow window. I looked at this with the flashlight, and he had been there, all right. There were footprints in the dirt, and he’d stepped on some of the flowers.

The policeman has never had reports of a prowler, which is not proof that there isn’t one, but nor is it good evidence. If the prowler’s activities have been in the news, the narrator may have read about the prowler, which then fuelled his delusion:

Then [the policeman] said that the village, since its incorporation in 1916, had never had such a complaint registered. He spoke with that understandable pride that we all take in the neighborhood.

The following sentence might be interpreted as symbolic. If only the narrator could work his way out of his madness, then the stranger would disappear:

I thought that if I could disengage the stranger from the night, from the dark, everything would be all right.

And it may not take much to send him over the edge:

I stood beside an old gentleman who was describing to a friend the regularity of his habits, and I had a strong impulse to crown him with a bowl of popcorn

Perhaps the best evidence that there is no stalker — that the man in the darkness is in fact himself — is that we find out on Madison Ave when he follows the housewife that he is capable of stalking in his own right. (He’s ‘stalking’ his wife.)

Like the main character of “The Chaste Clarissa”, and a number of other protagonists in Cheever’s stories, this guy does not see women as fully human. Once past their youth, women are uninteresting to him:

That night, I decided to stay in town and go to a cocktail party. It was in an apartment in one of the tower hotels-way, way, way up. As soon as I got there, I went out onto the terrace, looking around for someone to take to dinner. What I wanted was a pretty girl in new shoes, but it looked as if all the pretty girls had stayed at the shore. There was a gray-haired woman out there, and a woman with a floppy hat, and Grace Harris, this actress I’ve met a couple of times.

What else has he done to women? What might he do? His description of this woman emphasises her fragility, as if he’s sizing her up for an attack:

She had fair hair and the kind of white skin that looks like thin paper. It was a very hot day but she looked cool, as if she had been able to preserve, through the train ride in from Rye or Greenwich, the freshness of her bath. Her arms and her legs were beautiful, but the look on her face was sensible, humorous, even housewifely, and this sensible air seemed to accentuate the beauty of her arms and legs. She walked over and rang for the elevator. I walked over and stood beside her. We rode down together, and I followed her out of the store onto Madison Avenue. The sidewalk was crowded, and I walked beside her. She looked at me once, and she knew that I was following her, but I felt sure she was the kind of woman who would not readily call for help. She waited at the corner for the light to change. I waited beside her. It was all I could do to keep from saying to her, very, very softly, “Madame, will you please let me put my hand around your ankle? That’s all I want to do, madame. It will save my life.” She didn’t look around again, but I could see that she was frightened. She crossed the street and I stayed at her side, and all the time a voice inside my head was pleading, “Please let me put my hand around your ankle. It will save my life. I just want to put my hand around your ankle. I’ll be very happy to pay you.” I took out my wallet and pulled out some bills. Then I heard someone behind me calling my name. I recognized the hearty voice of an advertising salesman who is in and out of our office.

Rachel

Characters who are not there, or who have been there, are as important in a short story as characters ‘on the stage’. We might call these influential backstories ghosts. (Events and places and pretty much anything can serve as a ghost.) In this case we have Rachel, upon whom our narrator’s happiness seems to depend. Is Rachel — her ‘second coming’ — part of the narrator’s hallucination? If he can imagine peeping Toms at the window and starts reading things into people’s faces that aren’t there, it’s more than possible that he wholly imagines the phone call from Rachel. Making this even more likely, he has earlier presented (from his own made-up examples) some scenarios in which Rachel might call him, which is why he takes the phone off the hook in the first place. Coincidentally (or not) those are the exact reasons she calls him.

[BEGINNING OF STORY] I decided not to answer the telephone, because I knew that Rachel might repent, and I knew, by then, the size and the nature of the things that could bring us together. If it rained for five days, if one of the children had a passing fever, if she got some sad news in a letter-anything like this might be enough to put her on the telephone, and I did not want to be tempted to resume a relationship that had been so miserable.

[…]

[END OF STORY] “Oh, my darling!” I shouted when I heard Rachel’s voice. “Oh, my darling! Oh, my darling!” She was crying. She was at Seal Harbor, It had rained for a week, and Tobey had a temperature of a hundred and four.

THEME OF “THE CURE”

Cheever seems to be saying something about happiness in this story, and I suppose it depends on the reader, what exactly that thing is:

Cheever’s stories are stories that make us ask ourselves how happy we are. They are stories that make us confront our demons, our hushed fears, our secret shames. They are stories (like “The Cure” and “Seaside Houses”) full of quiet despair.

from the Things Mean A Lot blog

Life is full of ups and downs. Descent into despair can just as easily turn for the better, preceding many years of happiness. (With a moral thrown in for good measure: So don’t give up, and hang yourself with a rope.)

Even if you’re terribly unhappy, you can conjure up a completely different life for yourself by imagining your life how you wish it were. Failing that, write about your imagined better life to relatives in an attempt to fool yourself.

What is ‘the cure’, exactly? Reaching such depths of despair that you start having hallucinations to make yourself feel better?

Like the previous story in this collection, and perhaps the previous story that Cheever wrote — “The Chaste Clarissa” — this story delves into the disconnect between appearances and reality, making “The Cure” a kind of evolution on “The Chaste Clarissa”:

The belief that a crooked heart is betrayed by palsies, tics, and other infirmities dies hard. I felt the loss of it that morning when I searched his face for some mark. He looked solvent, rested, and moral-much more so than Chucky Ewing, who was job hunting, or Larry Spencer, whose son had polio, or any of a dozen other men on the platform waiting for the train. Then I looked at his daughter, Lydia. Lydia is one of the prettiest girls in our neighborhood. I’d ridden in on the train with her once or twice and I knew that she was doing voluntary secretarial work for the Red Cross. She had on a blue dress that morning, and her arms were bare, and she looked so fresh and pretty and sweet that I wouldn’t have embarrassed or hurt her for anything in the world. Then I looked at Mrs. Marston, and if the mark was anywhere, it was on her face, although I don’t understand why she should be afflicted for her husband’s waywardness. It was very hot, but Mrs. Marston had on a brown suit and a worn fur piece. Her face was sallow and plain, but it was wreathed, even while she watched for the morning train, in an impermeable smile. It was a face that must have seemed, long ago, cut out for violent, even malevolent, passion. But years of prayer and abstinence had expunged the inclination to violence, I thought, leaving only a few ugly lines at the mouth and the eyes and rewarding Mrs. Marston with an air of adamant and fetid sweetness.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE IN “THE CURE”

SURPRISE

In this short story, Cheever demonstrates the technique of the ‘sentence level surprise’. Surprise in general is essential in any good story. Plot = surprise. And surprise should happen at the macro and at the micro level. When the narrator bends down towards the hand prints his children have left on the wall, we expect him to wipe them off. But he kisses them. This isn’t entirely unexpected — the reader is already aware of his increasing loneliness and desperation, but at a sentence level, that’s not what we expect, especially when it’s hot on the heels of a borderline sociopathic stalking incident.

As soon as I stepped into the living room, I noticed on the wall some dirty handprints that had been made by the children before they went away. They were near the baseboard and I had to get down on my knees to kiss them

At the story level, it comes as a complete surprise (to this reader, anyhow) that the narrator is happy, reunited with his wife and children, living in the suburbs for many years since.

In my edition of collected short stories, the page breaks before the word ‘drunk’, but I’m sure this is just a coincidence of printing and page layout:

Then I came home one night and found Maureen, the maid, dead drunk.

Naturally, I thought he’d found the maid dead.

UNRELIABLE NARRATION

Here’s the thing about unreliable narrators: The ‘ghost’ is very important. Sure enough, our narrator also has a ghost. (See above.)

Some people tell writers to avoid adjectives like the plague, that they weaken the prose. But adjectives do have their uses, as demonstrated by Cheever in this story. Specifically, his use of ‘fiercely uninvested adjectives’. As Douglas Bauer says in his book on craft, The Stuff Of Fiction:

John Cheever’s story “The Cure” beautifully illustrates the characteristics of narrative precision and restraint. It is one of Cheever’s classic portraits of life in exurban New York, that country of rueful courtesies and decorous longing he made ineffably his own. The story begins with the narrator telling us:

My wife and I had a quarrel, and Rachel took the children and drove off in the station wagon. Tom didn’t appear-or I wasn’t conscious of him-until they had been gone for about two weeks, but her departure and his arrival seemed connected. Rachel’s departure was meant to be final. She had left me twice before-the second time, we divorced and then remarried-and I watched her go each time with a feeling that was far from happy, but also with that renewal of self-respect, of nerve, that seems to be the reward for accepting a painful truth. As I say, it was summer, and I was glad, in a way, that she had picked this time to quarrel. It seemed to spare us both the immediate necessity of legalizing our separation. We had lived together-on and off-for thirteen years: we had three children and some involved finances. I guessed that she was content, as I was, to let things ride until September or October.

We immediately hear in the narrator’s account a tone of extraordinary, even eerie dispassion that is at odds, to say the least, with the circumstances he is describing. He presumes his marriage is ending, that his children will be taken from him, that he will be forced to leave the comfort and history of his house, and yet he offers all this to us in a voice of resoundingly practical detachment. I particularly admire Cheever’s use of the pallid and almost offhand “glad”, with which the narrator twice characterizes his feelings about his wife’s choice of summer as the season for departure. Glad? we think. He may as well be confirming a Sunday morning tee time. Oh, good, I’m glad it’s ten. That’ll leave me time to clean out the garage.

This very mismatch of events and the abandoned husband’s apparent attitude toward them conveys not the absence, but the nearly palpable denial of emotion. In other words, feeling, sentiment, is very much present from the outset, but thoroughly tamped down, creating a mood of disquieting emotional unreliability. We feel sentiment in these sentences not because it is displayed but because it is under such repressive pressure we can sense the struggle required to keep it from escaping. Were the narrator to launch his story with a wail, some high keening of distress, the tone might at first sound more recognizable and seem more understandable to us but would quickly lose its strength and interest simply because it was, in our reflexive predetermination of how these domestic traumas affect those involved so much the sound we assumed we would hear. I do not believe it would produce the same energetic sentiment, the tension and curiosity, as does Cheever’s narrative restraint, which he accomplishes by giving the husband a voice of discordant calm. This voice, perfectly pitched, continues as the narrator explains his rational plan for passing the summer nights alone.

Logical as his decisions may be, affectless as is the tone in which they are explained, we recognize in the motives behind them the emotional turmoil he is so determined to keep dormant. Furthermore we begin to learn that he recognizes it, too. I knew enough to avoid the empty house in summer dusk. In other words, the texture of sentiment in the story is, with masterful subtlety, becoming gradually its surface as well as its substratum.

At this point the story takes a turn as the gathering strength of his loneliness and sorrow competes with his refusal to look directly at it. Waking in the the night and unable to get back to sleep, he goes downstairs to read. “Our living room is comfortable. The book seemed interesting.” (The fiercely uninvested adjectives, the reportorial flatness continues.) And then, after a few minutes,

I heard, very close to me, a footstep and a cough. I felt my flesh get hard — you know the feeling — but didn’t look up from my book, although I felt that I was being watched. … Then a fear, much worse than the fear of the fool outside the window, distracted me. I was afraid that the cough and the step and the feeling I was being watched had come from my imagination. I looked up.

I saw him all right, and I think he meant me to; he was grinning.

For the first time in the story real emotion explicitly appears on the narrative surface. (Being “glad” earlier, or his offering that he “likes” the house he’s about to lose — these hardly count.) Not only does it appear, he labels it for us and in so doing acknowledges that it has. More than that, he confesses that he wonders if he’s hearing and seeing things, a deeper admission that what’s going on inside him is considerably more turbulent than he’s insisted.

Douglas Bauer

STORY SPECS OF “THE CURE”

Initially published in The New Yorker, July 1952.

4,900 words.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH “THE CURE”

This short story reminds me a little of the children’s novel from the exact same year, Ginger Pye by Eleanor Estes (of The Hundred Dresses fame). Though this is a children’s book through and through, it’s also a family drama with the crime subplot of what Estes calls ‘a mysterious footstepper’. This footstepper wears an old, mustard-yellow hat and the children are not sure whether he is even real or not. Their theory is that he is after their new puppy.

Incongruously, this story also reminds me a little of the harrowing short story by Mary Gaitskill that appeared in the New Yorker many years after this one. This time, Gaitskill gets into the mind of a rapist. I’m reminded of that story because of the scene in which Cheever’s narrator follows a woman because he wants to put his hands around her ankle, and continues to follow her down the street knowing that she is unnerved — in fact, he has picked her because she seems to be the type who wouldn’t cause him any grief should he molest her. This is a very uncomfortable scene, but Gaitskill crafted an entire short story out of this kind of ‘discomfort’.

You can listen to Jennifer Egan read Gaitskill’s story The Other Place here.

See also: Mary Gaitskill on The Other Place and What Can We Steal From The Other Place?

WRITE YOUR OWN

Cheever’s brief here might have been ‘to write a newsy letter reassuring a relative that all is well, but give the reader more than enough information to wonder how on earth things can be well.’ This is a story of one man’s descent into madness. Has he resurfaced?

In the short story anthology Certifiable Truths: stories of love and madness, edited by Jane Messer, Messer says in the introduction that so many of the ‘crazy’ stories had to do with love, which explains the subtitle. In Cheever’s story, too, the narrator’s delusional experiences are as a result of lost love. Are there other things in life that can lead to such acts? Or is love/lost love indeed the best desire-line to go with?

In order to paint your narrator as unreliable, make use of surprise at every level, and don’t forget to make use of your folder of ‘fiercely uninvested adjectives’.