Even if you’ve not heard much of Angela Carter, “The Company of Wolves” and other subversive stories have probably influenced some of your other favourite authors.

When I ask Gaiman who his favourite fairy tale character is, he says he fell in love with Red Riding Hood when reading Carter. … in order to interpret Gaiman’s taste, you need to know that Carter’s take on the tale was “The Company of Wolves”, an ornately told story in which the heroine makes a relatively late appearance in a savage, sexual world, not a small child skipping along a path but a daring pubescent girl who strips naked, laughs in the face of danger and sleeps with the wolf — rendering him post–coitally “tender” — in her dead grandmother’s bed.

Interview between Gaby Wood and Neil Gaiman, The Telegraph

The queen of sexual subversiveness…must be the late Angela Carter. Like [Edna] O’Brien, Carter can write a very convincing sex scene. And also like her, she almost never lets it be only about sex. Carter nearly always intends to upset the patriarchal apple cart. To call her writing women’s liberation is to largely miss her point; Carter attempts to discover paths by which women can attain the standing in the world that male-dominated society has largely denied them, and in so doing she would liberate all of us, men and women alike. In her world, sex can be wildly disruptive.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

All stories are about wolves. All worth repeating, that is. Anything else is sentimental drivel.

Margaret Atwood

WHERE TO LISTEN

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE COMPANY OF WOLVES”

Most modern English readers will be familiar with the brothers Grimm version of Little Red Riding Cap, which turned into Little Red Riding Hood when reaching England. (In fact, the Grimms offered several different endings to their tale, and the ending in which Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother trap and capture the wolf without the help of any woodcutter is not the one that gained traction in the Victorian era, with very specific ideas about what constituted femininity.)

For this revisioning of Little Red Riding Hood, Angela Carter has used as hypotext an oral folktale collected around 1885, the one translated from P. Delarue and M. L. Teneze, Le conte populaire Français (The French Popular tale), published by Erasme, 1957. It’s called ‘The Grandmother’s Tale‘.

Carter takes several elements from this that other, more popular versions don’t have:

- The wolf is a werewolf (a ‘bzou’)

- There is a cat

- The wolf, in grandmother’s clothing, tells Little Red Riding Hood to throw her clothes onto the fire as she won’t be needing them anymore

- The bzou ties a woollen string to Little Red Riding Hood’s foot

In Carter’s revisioning, we have a transgressive, subversive ending. Reaching the grandmother’s house first, the wolf kills the grandmother then waits for Red Riding Hood meaning to sexually assault her. Surprisingly and disturbingly for the reader, Red Riding Hood is not repulsed by her grandmother’s killer; rather, she settles down to make a life with the ‘Wolf’.

STORYWORLD OF “THE COMPANY OF WOLVES”

PLACE

Many retellings of fairy tales have an updated modern setting, or feature a mixture of old-world and new-world details. This is not one such story — it feels firmly embedded in the fairytale world of the Grimms.

The cold, famished environment ups the stakes, which is a lovely touch since my childhood versions of Red Riding Hood seem to be set in sunny, happy forests:

It is winter and cold weather. In this region of mountain and forest, there is now nothing for the wolves to eat. Goats and sheep are locked up in the byre, the deer departed for the remaining pasturage on the southern slopes — wolves grow lean and famished.

Details are chosen to make this setting feel like a very unpleasant place:

acrid milk and rank, maggoty cheeses

TIME

The main story starts on Christmas Eve, with Little Red Riding Hood trudging through the woods to deliver some Christmas goodies to her almost-dead grandmother. Since the hypotext is an oral tale from the mid to late 1800s, then we can safely assume this is set at the same time.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

This is a world where the characters believe in all sorts of folk remedies and supernatural goings-on, which is just as real to them as religion is for many people today.

Seven years is a werewolf’s natural span but if you burn his human clothing you condemn him to wolfishness for the rest of his life, so old wives hereabouts think it some protection to throw a hat or an apron at the werewolf, as if clothes made the man.

Songs are important to the customs of this culture, and Angela Carter knows what all of them are called. A threnody (for death), a prothalamion (for marriage).

CHARACTERS IN THE COMPANY OF WOLVES

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD

The girl is first introduced as a ‘strong-minded child’. This is not the happy-go-lucky, innocent, carefree little girl I see in my childhood stories, ‘skipping’ through the forest unaware of the dangers. This is a Katniss Everdeen type of character who ‘trudges’ through the woods (with a knife in her cheese basket):

She is quite sure the wild beasts cannot harm her although, well-warned, she lays a carving knife in the basket her mother has packed with cheeses.

If she is unafraid of the woods it’s not because she is wholly naive, but simply that ‘she has been too much loved ever to feel scared’. This little girl is not a starving victim. Nonetheless:

Children do not stay young for long in this savage country. There are no toys for them to play with so they work hard and grow wise but this one, so pretty and the youngest of her family, a little late-comer, had been indulged by her mother and the grandmother who’d knitted her the red shawl that, today, has the ominous if brilliant look of blood on snow. Her breasts have just begun to swell; her hair is like lint, so fair it hardly makes a shadow on her pale forehead; her cheeks are an emblematic scarlet and white and she has just started her woman’s bleeding, the clock inside her that will strike, henceforward, once a month.

Near the end of the story, Little Red Riding Hood’s shawl is not ‘red’ but ‘scarlet’ (‘in spite of the scarlet shawl’). Scarlet, more than red, has overtones of sexuality, and also of blood: ‘it was as red as the blood she must spill’.

She closed the window on the wolves’ threnody and took off her scarlet shawl, the colour of poppies, the colour of sacrifices, the colour of her menses, and, since her fear did her no good, she ceased to be afraid.

THE WOLF

When retelling this tale the writer first decides: Are the wolves in the new story really wolves, or are they men? Many modern illustrations of the wolf in LRRH have him wearing clothes, and he talks, of course. Perhaps the wolf in this story is no more human than those more innocent versions. Their howls are reinterpreted by Angela Carter as religious songs (canticles), in a particularly masterful stroke:

There was a hunter once, near here, that trapped a wolf in a pit. This wolf had massacred the sheep and goats; eaten up a mad old man who used to live by himself in a hut halfway up the mountain and sing to Jesus all day

It becomes clear that in the world of the story the wolves are like men but not. These are man-wolf hybrids, not in the Beatrix Potter clothes-wearing way, but in a werewolf (lycanthrope) kind of way:

a wolf came slinking out of the forest, a big one, a heavy one, he weighed as much as a grown man…The hunter jumped down after him, slit his throat, cut off all his paws for a trophy.

Next we are told the story of the woman whose werewolf husband disappeared on her wedding night, only to reappear as a man years later after she had remarried and started a family: ‘I wish I were a wolf again, to teach this whore a lesson!’ So a wolf he instantly became and tore off the eldest boy’s left foot before he was chopped up with the hatchet they used for chopping logs.

FEMINISM

Angela Carter was among the first feminist writers to re-envision the classic fairytales, along with Anne Sexton, Olga Broumas and Tanith Lee.

Knowing that Angela Carter was a feminist writer, I automatically assume a feminist message. But what is the ideology?

If there’s a beast in men, it meets its match in women, too.

Angela Carter

Women are their own sexual agents.

In her book Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked, Catherine Orenstein writes:

In the second half of the twentieth century, a proliferation of revisions of “Little Red Riding Hood” turned the tale around to teach a new lesson. Storytellers from the women’s movement and beyond reclaimed the heroine and her grandmother from male-dominated literary traditions, recasting the women as brave and resourceful, turning Red Riding Hood into the physical or sexual aggressive, and questioning the machismo of the wolf. Their new heroines dominate the plot, sometimes with humour or strength and frequently with a libido more than equal to the wolf’s.

So in Carter’s story, she says women are not always victims, even in the most dire circumstance. Women are not to be used for sex as passive victims. Even though this story probably ends in death (of her human self) for Little Red Riding Hood:

All the better to eat you with.

The girl burst out laughing; she knew she was nobody’s meat. She laughed at him full in the face, she ripped off his shirt for him and flung it into the fire, in the fiery wake of her own discarded clothing.

From Catherine Orenstein:

In Carter’s “Red Riding Hood” -related tales, and in the film, the heroine’s wolf is not her oppressor, nor her opponent, nor her ravisher. Rather than besting the beast, the heroine incorporates it. The protagonists — both heroine and villain — move back and forth between the forms of human and beast, and each is by turns tender and aggressive. Their parallel transformations suggest their interrelated identities that encompass darkness and brightness, innocence and evil at once. Her heroine’s bestial side is an acknowledgement not only of her natural sex drive but also of her sexual complexity.

The woman from the first part of the story who inadvertently married the werewolf is mistreated both by the werewolf husband (once he returns) and also by the new husband, who beats her when she cries for the first. In marriage, woman is victim. When Little Red Riding Hood chooses a life (or death) outside the institution of marriage with a creature who killed her grandmother, is she really choosing so badly, if the alternative is a husband who will most likely beat her?

She will lay his fearful head on her lap and she will pick out the lice from his pelt and perhaps she will put the lice into her mouth and eat them, as he will bid her, as she would do in a savage marriage ceremony.

RELIGION

This society is a religious one, as well as a supernatural one. Granny ‘has her Bible for company, she is a pious old woman.‘ … ‘… now call on Christ and his mother and all the angels in heaven to protect you but it won’t do you any good.‘

I wonder if we’re to make something of the canticles of the wolves:

There is a vast melancholy in the canticles of the wolves, melancholy infinite as the forest, endless as these long nights of winter and yet that ghastly sadness, that mourning for their own, irremediable appetites, can never move the heart for not one phrase in it hints at the possibility of redemption; grace could not come to the wolf from its own despair, only through some external mediator, so that, sometimes, the beast will look as if he half welcomes the knife that despatches him.

If the wolves ‘half welcome’ the knives that despatch them, is the human analogy belief in heaven, feeling always like a sinner, and that death is a welcome escape from a tough life in the middle ages? Sex is mostly taboo in this cultural climate — people must always feel guilty for their animalistic instincts. The girl, in the end, breaks free of such taboos by embracing all that is bad.

[Little Red Riding Hood] stands and moves within the invisible pentacle of her own virginity. She is an unbroken egg; she is a sealed vessel; she has inside her a magic space the entrance to which is shut tight with a plug of membrane; she is a closed system; she does not know how to shiver. She has her knife and she is afraid of nothing.

STORYTELLING TECHNIQUE IN “THE COMPANY OF WOLVES”

Who does not sense, through her powerful evocations, the pricking of thorns, the awcracking stringiness of granny, the jangling of bed springs, the licking of a big cat’s tongue, the soft luxurious furs and velvets and skin, and the piercing contrasts with ice, glass, metal?

Cognitive theorists of language have identified such travelling movements and embodied presences in narrative as prime conductors of readerly empathy, replicating the motions of thought itself as it models scenes and experiences in the mind’s eye. Carter’s mastery of these effects brings about a quality of hallucinatory reality, dream-like in its close-up intensity, that wraps the products of her unleashed fantasy. She knew what wordpower could do: “No werewolf make-up in the world can equal the werewolf you see in your mind’s eye,” she wrote.

Marina Warner

OPENING

One beast and only one howls in the woods by night.

The wolf is carnivore incarnate and he’s as cunning as he is ferocious; once he’s had a taste of flesh then nothing else will do.

On second reading, the first sentence has me wondering which beast Carter refers to. The encyclopedia following sentence suggests she refers to the wolf, but might she instead be referring to the beast inside the adolescent girl? Her sexual desires?

WORD CHOICE

Certain vocabulary evokes an earlier time in the evolution of English. Of course, these tales were transcribed when English looked far different than it does today:

benighted traveller – this kind of adjectival phrase was far more common in Shakespeare’s day.

starveling ribs

Even punctuation has evolved over the years, and language can seem old if we make use of, say, exclamation marks mid-sentence:

See! sweet and sound she sleeps in granny’s bed

Another technique Angela Carter uses to make her prose sound ‘olde’ is by making use of words which are still in use, but remain mostly in set phrases: The wolfsong is the sound of the rending you will suffer. These days we’re most likely to hear ‘rending’ in ‘heart rending’ – more commonly ‘heart wrenching’. Here it means to tear apart savagely.

Despite using every tool in the writer’s box to create an ominous atmosphere, there are odd touches of humour. There’s something about the word ‘snout’ and the mundanely specific detail of ‘straining the macaroni’:

There is no winter’s night the cottager does not fear to see a lean, grey, famished snout questing under the door, and there was a woman once bitten in her own kitchen as she was straining the macaroni.

IMAGERY

Similes comparing tangible and intangible things seem particularly clever: They are grey as famine, they are as unkind as plague.

Words are chosen for their more-than-one meaning: grave-eyed children

The scarlet shawl is both a symbol of childhood and of violent sexuality.

What shall I do with my shawl?

Throw it on the fire, dear one. You won’t need it again.

There is the extended metaphor of the change of season being like a door on a hinge. One door shuts (childhood, innocence) while another opens into solstice (adulthood/death).

DETAIL

Of grandma’s house: ‘Two china spaniels with liver-coloured blotches on their coats and black noses sit on either side of the fireplace. There is a bright rug of woven rags on the pantiles…’

It seems the way to make an old tale seem new is by adding super-specific details that no one else has done before.

Details also make a disturbing scene all the more disturbing. Usually we’re not given too much detail about how the wolf deals with his crime, but here:

He burned the inedible hair in the fireplace and wrapped the bones up in a napkin that he hid away under the bed in the wooden chest in which he found a clean pair of sheets. These he carefully put on the bed instead of the tell-tale stained ones he stowed away in the laundry basket. He plumped up the pillows and shook out the patchwork quilt, he picked up the Bible from the floor, closed it and laid it on the table. All was as it had been before except that grandmother was gone.

TENSE

The story is written in a mixture of past and present tense. This works beautifully, because this is in essence a ‘fireside scary story’, with an unseen narrator making use of oratory techniques to make the scary story even scarier. This requires present tense for the scariest bits, moving into past tense to explain back story. ‘There was a hunter once, near here…’ places the reader ‘near here’ (wherever the reader happens to be) and begins a shift from present to past tense. Angela Carter switches often between paragraphs from past to present tense, yet for some reason it doesn’t jar.

POINT OF VIEW

Second person POV is used to ominous effect:

You are always in danger in the forest, where no people are. Step between the portals of the great pines where the shaggy branches tangle about you, trapping the unwary traveller in nets as if the vegetation itself were in a plot with the wolves who live there, as though the wicked trees go fishing on behalf of their friends — step between the gateposts of the forest with the greatest trepidation and infinite precautions, for if you stray from the path for one instant, the wolves will eat you.

STORY SPECS

Irreverence and anarchy, scepticism and non-conformity were qualities Carter shared with fellow Londoners in the reverberating force field around the Beatles, the Stones, satirists like Lenny Bruce and the founders of Oz magazine. Curiosity about possible sexualities was a central theme, reflected in the cult status of Jean-Luc Godard’s films of that time. “The Company of Wolves” first appeared in Bananas, the literary magazine that the novelist Emma Tennant began and edited from 1975 to 1979, where several reworkings of myths and fairy tales by other writers — Sara Maitland, Michelene Wandor and Tennant herself — also appeared.

Marina Warner

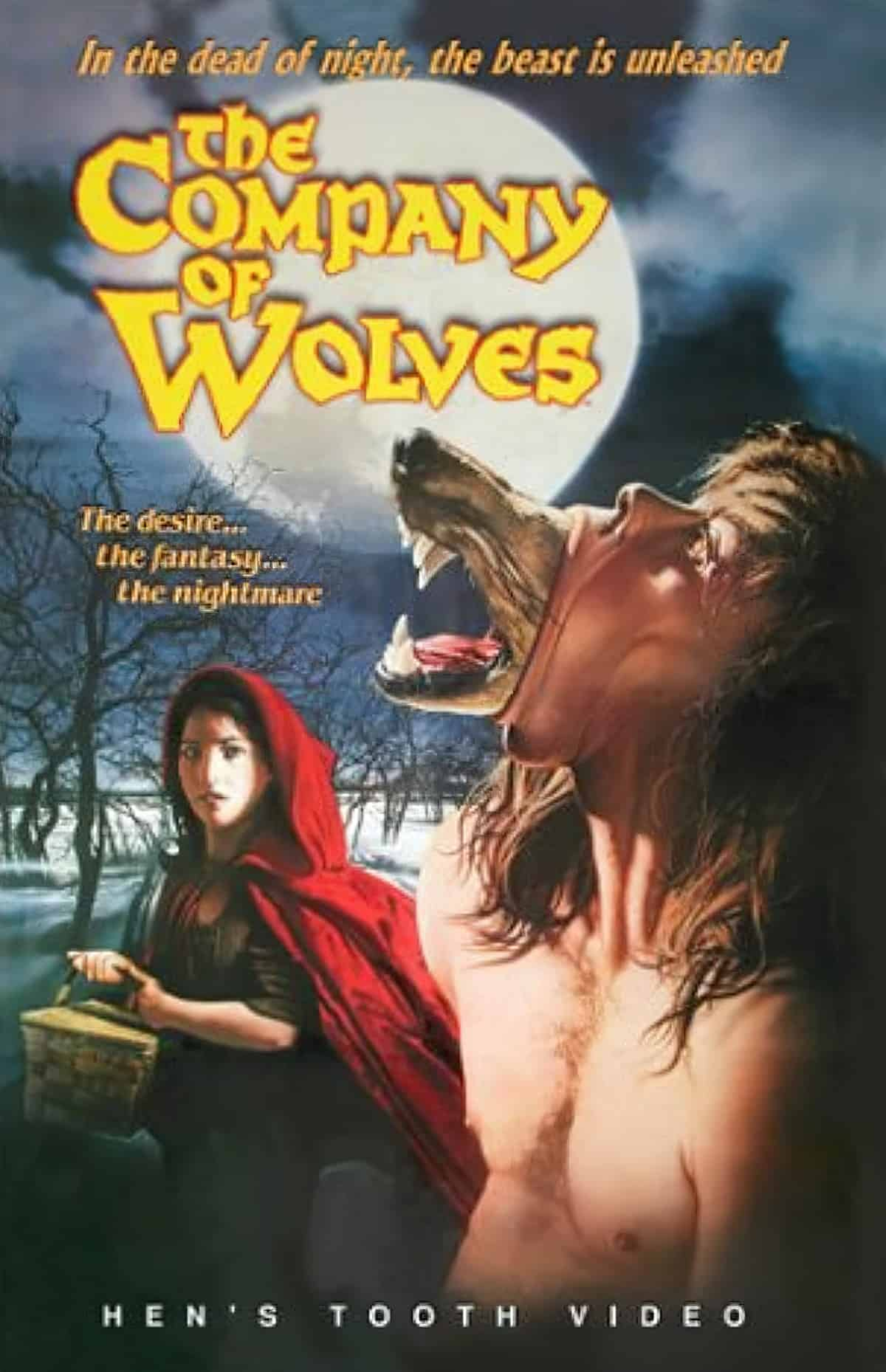

I have it on good authority that the film adaptation of this masterful short story is best avoided, though others say they really enjoy it:

I’m not willing to seek it out. From Catherine Orenstein:

The movie’s ending, which Carter reportedly disliked, differs from the climax of her short story, in which the wolf is tamed, and morning finds the heroine sleeping softly in his arms.

3400 words

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The most obvious text for comparison and contrast is the story’s hypotext — take your pick. Although the Disneyfied versions are well-known to young readers, a comparison with the Grimms’ version may yield more similarities, at least in tone. Definitely check out The Grandmother’s Tale, linked above.

Other 20th C feminist re-visionings of Little Red Riding Hood from Catherine Orenstein:

- A 1972 revision by a group of four women called the Merseyside Women’s Liberation Movement. (Called simply “Little Red Riding Hood”) (Good luck finding it – Little Red Riding Hood encounters the wolf but this time she has backup, and is saved by her grandmother who has a background in wolf fighting — this reminds me of the grandmother in Roald Dahl’s The Witches. Little Red Riding Hood also helps, by remembering the sewing knife in her basket.)

- Anne Sharpe’s 1985 tale “Not So Little Red Riding Hood” (Little Red Riding Hood dispatches her rapist using karate. By the time she gets to grandma’s she’s forgotten the incident altogether.)

- Rosemary Lake’s “Delian Little Red Riding Hood” from the collection Once Upon a Time When The Princess Rescued The Prince (in which the two women have a good laugh about the incident while together in the wolf’s belly. They cut themselves out with sewing scissors.)

- James Garner’s “Politically Correct” version (in which the grandma is “in full physical and mental health” and “fully capable of taking care of herself as a mature adult”.)

- Rachel Yep’s “Little Red Riding Hood — The Real Version” (in which Grandma “used to work in the US Army. Grandma ends up killing a whole pack of wolves and makes wolf soup for dinner.)

- Paul Musso’s comic strip “You Are What You Eat” (in which Little Red Riding Hood makes no appearance at all. The plot begins in the cabin in the woods in the middle of the night. The wolf gets into Grandma’s house via an open window. The wolf has a hilarious tussle with surprisingly feisty grandma and we never find out who wins. Only a profile in shadow can be seen, of indeterminate species, watching the sunrise amidst a landscape of torn gingham and fur.)

- Olga Broumas’ “Little Red Riding Hood” (in which the story’s sexual subtext is transformed — there is no wolf at all. It’s a lesbian tale.)

- D.W. Prosser’s “Red Riding Hood Redux” (in which Little Red Riding Hood shoots the wolf with a 9-mm Beretta. She sends the hunter off to a self-help group called White Male Oppressors Anonymous.)

- Roald Dahl’s “Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf” (in which LRRH ‘whips a pistol from her knickers’ after noticing his thick pelt. Then she grabs the pelt and wears it. As Orenstein notes: Dahl is no feminist. This is a faux-feminist revisioning, in which Dahl ‘takes a satirical swipe at feminism that confuses female emancipation with the power to consume: Her victory is a fashion statement.’)

- Stephen Sondheim’s musical “Into The Woods” (in which LRRH and her grandmother skin the wolf. Little Red Riding Hood trades her red riding hood in for a wolf fur stole and hat. This is similar to Dahl’s version.)

- Tanith Lee’s “Wolfland” (in which the young “Lisel” is sent to viist her eccentric, rich grandmother in a chateau surrounded by wolves. The grandmother becomes a werewolf each night. Lee’s female werewolf is not sexual — she transforms to escape the bonds and duties of marriage and afterwards has nothing to do with men at all, except for a housepet dwarf. This is the grandmother’s way of getting rid of men. Born into the werewolf line, Little Red Riding Hood will become one too.)

- Pepsi One Commercial starring Kim Cattrall (playing as Samantha from Sex In The City, who frequently parodies stereotypically male sexual behaviour. Here she is a paradox: she is liberated sexually but she is warned she has to diet.)

Keep attuned to faux-feminist retellings of Little Red Riding Hood. Many stories are about how women ‘tame’ men sexually and otherwise.

Other tales have Little Red Riding Hood kill the wolf with the glee of a stereotypically male warrior. This is an inversion, sure, but not a subversion.

Orenstein calls Carter’s retelling an example of “Beast Feminism”: a modern tradition in which the heroine wears or becomes her furry nemesis (free love/furry legs, ‘grrrrl’ bands who define themselves with a grrrowl, Women Who Run With The Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola in 1992 and so on. In keeping with beast feminism, ‘bitch’ has evolved as a compliment.)

I am also reminded of the French film Fat Girl (original title) “À ma soeur!” but I can’t tell you much more about that without spoiling the ending. I recommend it for the hardy viewer with a high tolerance for ambiguity and complex emotional reactions. I have recommended this film to friends who tell me they don’t want to watch a film about a ‘fat girl’ because you have to be in the mood for revisiting the fat-phobia that is rife throughout society, but it’s worth pointing out that the original French title means ‘To my sister!’ (or something like that). In other words, the English title is disappointing given the film is about so much more than the protagonist’s size.

WRITE YOUR OWN

There are lots of feminist re-workings of classic tales. Many of the modern ones have the girl exacting her own violent revenge, as a stand-in man. Others get rid of the man completely by replacing him with another female character. Is it possible to rewrite one of those old, classically sexist tales in a genuinely feminist way, or are we better to move away from fairytales altogether if we want a feminist story? Which of the classic tales offends you the most? How would you re-do it?