WHAT HAPPENS IN THE CHASTE CLARISSA

A twice-divorced philanderer holidays where he has always holidayed, on Martha’s Vineyard. On the ferry he meets for the first time a beautiful young woman who has recently married into a bird-watching, rock-collecting family of average Joes, but her husband won’t be joining Clarissa on the island, so our viewpoint character decides immediately that she shall be his next conquest. He sets up a plan to make this happen.

SETTING OF THE CHASTE CLARISSA

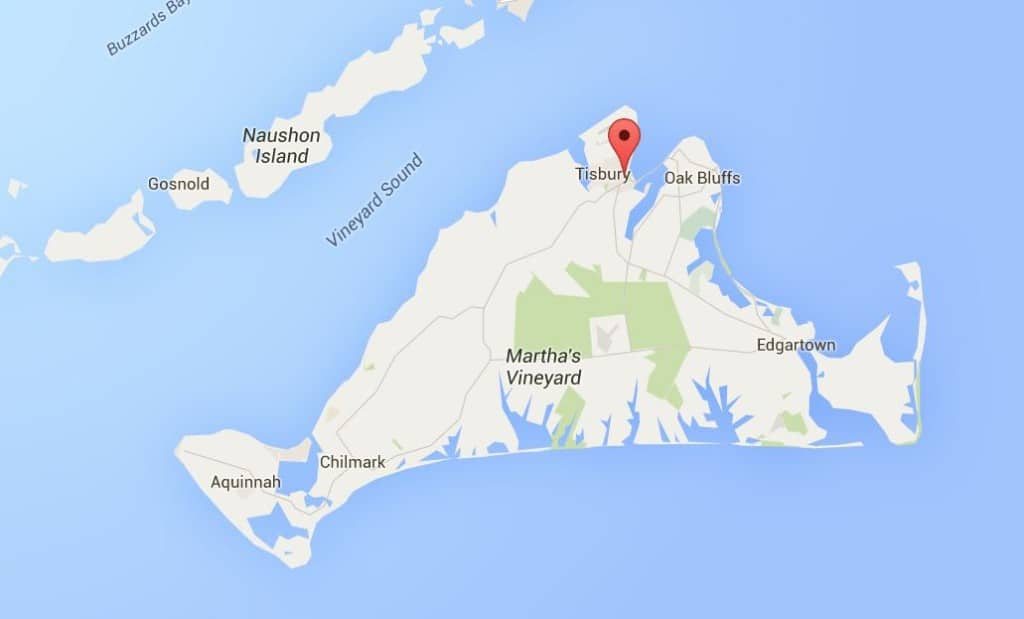

Place

Vineyard Haven is a community within the town of Tisbury on Martha’s Vineyard in Dukes County, Massachusetts, United States.

Time

Published in 1952, this is a story set in the same time. This was The Decade of the Housewife, an era which we still tend to idealise, forgetting perhaps, the problems described by Betty Friedan and others.

Milieu

As usual in Cheever’s stories thus far, “The Chaste Clarissa” is a story about upper-class people with upper-class issues. We have holiday homes and housemaids and copious amounts of spare time. Whatever else was going on in the world is irrelevant to these characters, underscored by the fact that this is set on a literal island.

CHARACTERS IN THE CHASTE CLARISSA

Baxter

Rogue charmers and tricksters are popular storytelling archetypes. Baxter embodies all of those characteristics. It makes no difference to an audience whether this character is the ‘good guy’ or the ‘bad guy’ — these characteristics are interesting either way. The reader is invested in finding out whether he achieves his goal.

“You’re lovely, Clarissa,” Baxter said.

“Well,” Clarissa said, and she sighed. “That’s just my outward self. Nobody knows the real me.”

That was it, Baxter thought, and if he could only adjust his flattery to what she believed herself to be, her scruples would dissolve. Did she think of herself as an actress, he wondered, a Channel swimmer, an heiress?

This short story is a great example of how a character must have both a ‘desire’ AND a ‘shortcoming/need’.

Baxter’s Shortcoming/Need: This has to be something that his holding the character back to the point where it’s ruining his life. Baxter is ruining his chance at true happiness by treating women as sexual conquests. Not only women, actually — Baxter sees other people as less than human, as explained in the first paragraph:

In a little while, the warning whistle would separate the sheep from the goats—that’s the way Baxter thought of it—the islanders from the tourists wandering through the streets of Woods Hole.

Baxter has already been through two marriage breakups, we are told in passing. Moreover, he’s not truly accepted by his community, allowed to holiday on the island only because he’s been holidaying there since childhood — subtext being that if he were to come in a stranger, he wouldn’t be accepted at all. So Baxter is lonely and isolated, by his own doing. Baxter’s psychological need is that he is alone, and trying to fill the void with sexual liaisons, come hell or highwater. He is also easily bored and stingy with material items, as he is with true affection.

The other important thing is to give the main character a moral need as well as a psychological need (above). A character with a moral need is always hurting others in some way.

Baxter’s Moral Need: If the main character is already aware of what he needs then there is no story. Sure enough, Baxter has no idea that how he interacts with women — preying upon the attractive ones while ignoring the middle-aged ones — is wrong. In some stories, the main character has a anagnorisis, but not in this one. Instead, the revelatory aspect of the story should happen within the reader: We should realise that Baxter’s view of women are wrong, and perhaps examine our own inherent beliefs about women and beauty.

Cheever isn’t shy of allegorical naming conventions and it’s possible that the name ‘Baxter’ (meaning ‘baker’) is related to the way in which Baxter ‘cooks up a plan’ to snag himself a lonely, beautiful woman to sleep with for the summer. Also, ‘baxter’ originally referred only to a ‘female baker’, and in this story, the psychological shortcomings of Baxter and Clarissa indeed line up, making each the flipside to the other, and therefore suited, in a strange sort of way.

Clarissa

My interpretation of Clarissa is informed by feminism. I believe Clarissa is not given a voice in this story — something Cheever does deliberately, at best guess — underscored most clearly in the scene where she pours Baxter tea and utters only four words the entire time, regarding his tea. The fact that she is pouring tea for a male guest she doesn’t even want is another way to underscore her subservient position inside an ostensibly privileged one of upper class idleness. Clarissa is in fact stuck inside a gilded cage, not necessarily because her marriage is unsatisfactory (reader expectations are subverted when we learn that she has written to her husband of Baxter’s kiss) but because her beauty is preventing her from interacting authentically with other people.

Another blogger reviewer writes something interesting about initially coming to terms with the character of Clarissa:

At one stage in the story, I was tempted to consider her a “Desperate Housewife”. Baxter offers to take Clarissa to the beach, where he is impressed, and this stuck in mind as well, by the whiteness of her skin. The attitude is memorable and so is the description of John Cheever. The woman acts as if she is naked, very embarrassed by the circumstance where one is only wearing a bathing costume, which seems to be too little for Clarissa.

Part of me thinks the ‘desperate housewife’ interpretation may be influenced by Marcia Cross’s character on the TV show of the same name — red-hair, white skin, long legs etc. But I also think we are used to this trope in stories, and we certainly don’t expect Clarissa to have told her husband about the kiss — we are far more used to stories involving an escalating sequence of minor deceptions. Think of all the dramas in which an illicit kiss goes unreported to a spouse, even though the audience is lead to believe that the marriage in question is robust.

“No,” she said. “No, Baxter, you’ll have to go. You just don’t understand the kind of a woman I am. I spent all day writing a letter to Bob. I wrote and told him that you kissed me last night. I can’t let you come in.” She closed the door.

Like Baxter, Clarissa has both a psychological need and a moral one:

Clarissa’s Psychological shortcoming: She is not taken seriously by the book-reading family she has married into. Strangers and acquaintances see only her beauty, not who she really is. Like Baxter, she is isolated. (This is what he senses immediately, and preys upon.) Like Baxter, she is also bored by her situation:

Her bare arms were perfectly white. Woods Hole and the activity on the wharf seemed to bore her and she was not interested in Mrs. Ryan’s insular gossip. She lighted a cigarette.

(Note that Baxter, too, has just lit a cigarette out of boredom.)

Clarissa’s Moral Shortcoming: The way Clarissa is consistently objectified makes her standoffish and mistrusting of strangers, though not without reason, as it turns out. This could be interpreted as a strength, because she spends most of the story seeming to see straight through this rogue charmer, but it turns out to also be her shortcoming. Her standoffishness has lead to loneliness, opening her vulnerability to a liaison such as this.

Mrs Ryan

‘Old Mrs Ryan’ is probably not that old by today’s standards, being the mother-figure of Bob, married to a 25-year-old. I put her between 40-50. She and the other female characters who crop up in this story are set in contrast to Clarissa. Mrs Ryan is Clarissa’s opponent because she cuts her off and looks down upon her.

“He’s isn’t coming at all,” the beautiful Clarissa said. “He’s in France. “He’s gone there for the government,” old Mrs. Ryan interrupted, as if her daughter-in-law could not be entrusted with this simple explanation.

Mrs Ryan is also Baxter’s opponent, because she seems to know his intentions with her daughter-in-law, and interrupts in a conversation they’re having at the house. However, Mrs Ryan is too self-absorbed to follow-through with her protection of Clarissa.

“What are you two talking about?” Mrs. Ryan asked, coming between them and smiling wildly in an effort to conceal some of the force of her interference. “I know it isn’t geology,” she went on, “and I know that it isn’t birds, and I know that it can’t be books or music, because those are all things that Clarissa doesn’t like, aren’t they, Clarissa? Come with me, Baxter,” and she led him to the other side of the room and talked to him about sheep raising. […] Stopping at the door to thank Mrs. Ryan and say goodbye, Baxter said that he hoped she wasn’t leaving for Europe immediately.

“Oh, but I am,” Mrs. Ryan said. “I’m going to the mainland on the six-o’clock boat and sailing from Boston at noon tomorrow.”

The Other Women

The women were tanned. They were all married women and, unlike Clarissa, women with children, but the rigors of marriage and childbirth had left them all pretty, agile, and contented. While he was admiring them, Clarissa stood up and took off her bathrobe.

Baxter, and possibly the reader, probably thinks that Clarissa takes off her bathrobe to impress him, and attract his eyes back to her. He even sees her coyness as another part of her beauty, whereas it could also be seen as extreme self-consciousness on the part of a woman who would love to go for a swim, but doesn’t want to be scrutinised by a leery man while doing so:

Here was something else, and it took his breath away. Some of the inescapable power of her beauty lay in the whiteness of her skin, some of it in the fact that, unlike the other women, who were at ease in bathing suits, Clarissa seemed humiliated and ashamed to find herself wearing so little. She walked down toward the water as if she were naked.

THEME IN THE CHASTE CLARISSA

Beauty correlates with stupidity in the dominant culture, seen most clearly in the case of beautiful young women.

Baxter’s is the dominant cultural view: He believes that beautiful women must be boring and stupid, and ordinary women are the only women with any character and personality.

The open-minded reader is given enough information in Cheever’s story to see that, in fact, Clarissa has many opinions of her own. But because she has kept them to herself for so long, dismissed by all those around her has stupid, these ideas rush forth without much in the way of synthesis, and Baxter is determined to interpret this as a form of stupidity, because a stupid woman suits his carnal purposes. The story ends at a point where the reader is unable to really get to know Clarissa, but there is nothing inherently stupid in what she says.

Baxter’s view of women and beauty is common throughout the culture even today, making this a rather timeless story. The stereotype of the beautiful bimbo is common even in children’s stories. If you take a quick look at other readers’ interpretation of this story, you’ll easily find an example of those who take Clarissa’s stupidity at face value.

Even a reviewer in The Spectator takes Clarissa’s stupidity at face value, praising Cheever’s story nonetheless:

…he could certainly contrive a really elegantly classical narrative like ‘The Chaste Clarissa’, in which a terrible old roué discovers that the way to seduce a beautiful but dumb wife is to tell her how intelligent her opinions are (‘It was as simple as that’, it gloriously ends).

The Spectator review of a Cheever biography

Are we supposed to view Clarissa as stupid? Take the following snippet of conversation:

“You know, those stones on the point have grown a lot since I was here last,” she said.

“What?” Baxter said.

“Those stones on the point,” Clarissa said. “They’ve grown a lot.”

“Stones don’t grow,” Baxter said.

“Oh yes they do,” Clarissa said. “Didn’t you know that? Stones grow. There’s a stone in Mother’s rose garden that’s grown a foot in the last few years.”

This exchange strikes me as so hyperbolic in its stupidity that Clarissa may be testing Baxter. For now, he fails the test: someone who truly believed in her intelligence would take the conversation further, challenging her to elaborate on how, exactly, stones grow, or laugh at her strange joke, but Baxter’s interest in Clarissa is purely sexual; for now, he fails to win her over.

Baxter put his arms around Clarissa and planted a kiss on her lips.

She pushed him away violently and reached for the door. “Oh, now you’ve spoiled everything,” she said as she got out of the car. “Now you’ve spoiled everything. I know what you’ve been thinking. I know you’ve been thinking it all along.”

Is falling for an inappropriate person a sign of stupidity? If so, Clarissa does a stupid thing by falling for this rogue’s charms. Then again, plenty of intelligent people find themselves in bad relationships. And perhaps this particular liaison is actually exactly what Clarissa needs in the moment? The unquestioning reader assumes Clarissa has ‘fallen for’ Baxter, but a modern reader may interpret it slightly differently: They are using each other equally.

“We could play cards,” Baxter said.

“I don’t know how,” she said.

“I’ll teach you,” Baxter said.

A problematic part of femininity is the acculturation that saying ‘no’ (especially to a man) is rude and unacceptable. It’s possible that Clarissa indeed knows how to play cards, and that this is her way of trying to turn him down.

Further evidence of Clarissa’s upperclass feminine acculturation:

“I think we’re like cogs in a wheel,” she said. “For instance, do you think that women should work? I’ve given that a lot of thought. My opinion is that I don’t think married women should work. I mean, unless they have a lot of money, of course, but even then I think it’s a full-time job to take care of a man. Or do you think that women should work?”

If we go with Cheever’s tendency to name characters allegorically, bear in mind that Clarissa is derived from the German name Clarice. Clarice in turn is derived from the Latin the word Clarus, which means “bright, clear or famous.” Might Cheever be referring to her intelligence rather than just to her shiny hair?

My interpretation is simply one of several, and a story thereby functions to either strengthen or challenge the reader’s pre-existing attitudes about women, intelligence and beauty. As Nodelman and Reimer say, morals are actually separate from their stories. They write about children’s literature, but the fact is equally true of all literature; ‘Anyone who expects a moral or a message is sure to find one. That this is the case reveals the degree to which messages or themes are separate from the texts readers relate them to. In seeking messages, readers tend to confirm their own preconceived ideas and values: to take ideas from outside the text and assume that they are inside it. That prevents them from becoming conscious of ideas and values different from their own.’

Related:

Why Are Smart People Usually Ugly was Slate’s The Explainer’s question of the year in 2011. (tl;dr: it’s a false premise).

TECHNIQUE OF NOTE IN THE CHASTE CLARISSA

The reader knows immediately Baxter’s intentions for Clarissa, though the unseen narrator never comes out and actually says, ‘Baxter intended to sleep with her’. Instead, we are given enough detail to work it out for ourselves. How does Cheever do this, exactly?

Clarissa is seen through what modern audiences would call ‘the male gaze’. Instead of talking to her middle-aged mother-in-law, Baxter speaks directly to her. That’s after admiring Clarissa’s beauty, pointing out specific body parts that he is objectifying. Any reader who has lived in the world knows how certain men respond to middle-aged women when beautiful young women are around, and this Baxter fits the stereotype.

The reader is also told that Baxter is only accepted on the island because he has been holidaying there since he was a child.

BAXTER KNEW that in trying to get some information about Clarissa Ryan he had to be careful. He was accepted in Holly Cove because he had summered there all his life. He could be pleasant and he was a good-looking man, but his two divorces, his promiscuity, his stinginess, and his Latin complexion had left with his neighbors a vague feeling that he was unsavory.

Baxter’s plan is explained via the unseen narrator:

“Well, thank you.” Clarissa lowered her green eyes. She seemed uncomfortable, and the thought that she might be susceptible crossed Baxter’s mind exuberantly.

STORY SPECS OF THE CHASTE CLARISSA

4,100 words

COMPARE WITH

Reading this story I’m reminded of the 1990s Simply Red song, So Beautiful. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=72cXVM-AYpo

SO BEAUTIFUL

I was listening to this conversation

Noticing my daydream stimulated me more

I was crumbling with anticipation

You’d better send me home before I tumble down to the floorYou’re so beautiful but oh so boring

I’m wondering what am I doing here

So beautiful but oh so boring, I’m wondering

If anyone out there really cares

About the curlers in your hair

My little golden baby, where have all your birds flown now?Something’s glistening in my imagination

Motivating something close to breaking the law

Wait a mo’ before you take me down to the station

I’ve never known a one who’d make me suicidal beforeShe was so beautiful but oh so boring

I’m wondering what was I doing there

So beautiful but oh so boring, I’m wondering

If anyone out there really cares

About the colour of your hair

My little golden baby, where have all your birds flown now?

The Simply Red song sounds like something Baxter might have hummed after another few more dates with the beautiful Clarissa. Like the narrator in So Beautiful, Baxter has a sexist, binary view of women. We know nothing about the woman Mick Hucknall sings about, but the reader is given limited information about Clarissa throughout the story and right at the end we get to hear something of what she says. The readers make up our own mind about whether Clarissa is stupid or just stifled. Baxter judges ‘stupid’ very quickly. It would be interesting to know what Cheever himself thinks of his own creation; I’m inclined to be generous at this point and suggest he’s testing the reader’s own sexism. There is nothing in what Clarissa says that depicts her as stupid. Will the reader take Baxter’s viewpoint at face value, or cast him as a non-empathetic bad boy?

[Baxter] heard people say that [Clarissa] was beautiful and stupid.

Cheever may well be challenging the reader to either determine Clarissa’s intelligence based on other people’s hearsay, or to work it out for ourselves.

WRITE YOUR OWN

The danger of writing stories such as these, in which the reader is almost dared to side with a scrupulous viewpoint character is that the reader can attribute such values to the writer. Yet this is one way of being subversive, provided the reader thinks. In this story, Cheever has challenged the reader to think about the correlation between female beauty and stupidity.

How else might these stereotypes be challenged, perhaps in a more modern setting? How might it be challenged in a children’s book? In a different genre? From the point of view of the misunderstood?