I bought The Collected Stories of John Cheever as a salve to heal my Mad Men withdrawals, and this is one of Cheever’s stories that absolutely reminds me of Mad Men. Stephen Bruce is a Don Draper character; his daughter is a Sally Draper type. Matt Weiner has cited Cheever as one source of inspiration for Mad Men, and in this story we have an early example of the sympathetic antihero.

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE STORY

A married man (on his second marriage) has an affair with a woman in his social circle. They are seen out and about, the man’s wife hires a private investigator and eventually the woman’s husband leaves her, taking their children to the country.

SETTING

The story opens with very specific geographical location:

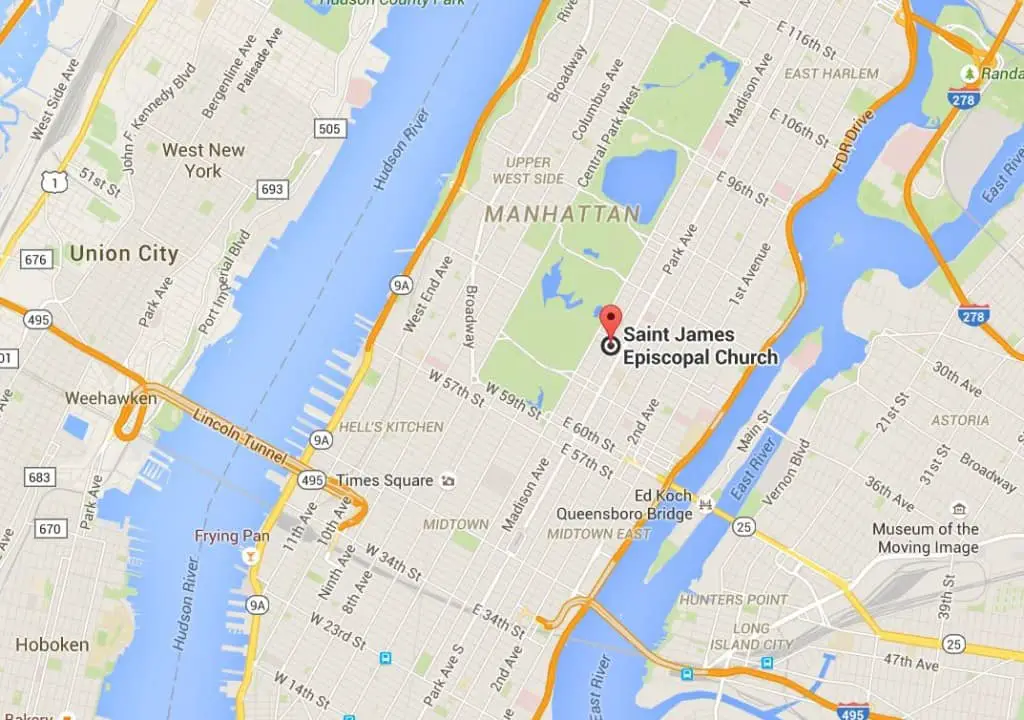

The bus to St. James’s—a Protestant Episcopal school for boys and girls-started its round at eight o’clock in the morning, from a corner of Park Avenue in the Sixties.

Next we’re given the exact time, and a description of the atmosphere at that time of day:

The earliness of the hour meant that some of the parents who took their children there were sleepy and still without coffee, but with a clear sky the light struck the city at an extreme angle, the air was fresh, and it was an exceptionally cheerful time of day. It was the hour when cooks and doormen walk dogs, and when porters scrub the lobby floor mats with soap and water.

Finally, to round off the introductory paragraph, we’re given a taste of the social class we’re dealing with:

Traces of the night-the parents and children once watched a man whose tuxedo was covered with sawdust wander home-were scarce.

The second paragraph opens with a sentence that lets us know the fall semester is about to begin. Cheever never leaves setting to the imagination — apart from the fact that Shady Hill is a made-up suburb, he is usually very specific about what sort of people we’re reading about and where they live, and what the weather is doing.

Milieu

This is a time in which black and white education is separate in America. Though some forward-looking individuals are starting to question the status quo, the majority of whites in this story are happy with segregation.

CHARACTERS

There are five children who board the bus at this story’s bus stop. The way they are introduced — some have given names while others go by non-specific monikers — show us the relationship to the narrator:

- Louise and Emily Sheridan

- The Pruitt boy

- Katherine Bruce

- The little Armstrong girl

Mr Pruitt etc.

Mr. Pruitt brought his son to the corner each morning. They had the same tailor and they both tipped their hats to the ladies.

We now know that the narrator is male (though anyone who’s read Cheever will know that a first person narrator of is is more than likely to be male.)

We are then bombarded with the details of people we don’t know and can’t yet visualise. This is to provide verisimilitude — to help us to believe that this world really exists, because any real world situation would be peopled with characters such as these.

Mrs Sheridan

Mrs Sheridan’s is the first name to really stick, because the narrator gives us a bit more to hang onto with her. The detail of her repeated and emphatic ‘yes’es places her firmly in the reader’s mind:

“Oh yes,” Mrs. Sheridan said, “yes.” She never gave a simple affirmative; she always said, “Oh yes, yes,” or “Oh yes, yes, yes.”

Again, I get the strong feeling that this narrator is writing with a male gaze. But as the paragraph continues, we see that the narrator is closely aligned with Mr Bruce, whose ‘male gaze’ we are privy to:

Mrs. Sheridan dressed plainly and her hair was marked with gray. She was not pretty or provocative, and compared to Mrs. Armstrong, whose hair was golden, she seemed plain; but her features were fine and her body was graceful and slender. She was a well-mannered woman of perhaps thirty-five, Mr. Bruce decided, with a well-ordered house and a perfect emotional digestion of those women who, through their goodness, can absorb anything. A great deal of authority seemed to underlie her mild manner. She would have been raised by solid people, Mr. Bruce thought, and would respect all the boarding-school virtues: courage, good sportsmanship, chastity, and honor. When he heard her say in the morning, “Oh yes, yes!” it seemed to him like a happy combination of manners and spirit.

Mrs Sheridan is probably the most sympathetic character to modern audiences — she has ‘aged’ the best. She is the forward-looking character, wanting to open up the conservative little white school to black students. How would the 1957 audience of The New Yorker have considered this issue? Racial segregation in schools was definitely a talking point, and had been since at least 1951, when Oliver Brown attempted to enrol his African American daughter into an all-white public school in Topeka, Kansas. In 1954, the Supreme Court outlawed segregated public education facilities for blacks and whites at the state level. But it wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that private schools such as St James in this story were required to end segregation.

Mr Bruce

We are encouraged to become suspicious of Mr Bruce’s intentions from the get-go:

Mr. Bruce, eavesdropping on their conversation, behind his newspaper … he was pleased, one morning, to get to the corner and find that Mrs. Sheridan was there with her two daughters and the dog, and that Pruitt wasn’t.

We soon find out Mr Bruce’s motivations: He is interested in getting to know Mrs Sheridan because he finds her sexually alluring. But he is not really interested in her as a person. He’s interested in her as a ‘catch’. He has already determined that she is recently bereaved due to the drowning of her young son, and that she has an unsatisfactory relationship with her own husband (after having seen them argue in public), and now he’s moving in for the kill:

She was excited at finding someone who seemed interested in her opinions, and she put herself at a disadvantage, as he intended she should, by talking too much. The deep joy we take in the company of people with whom we have just recently fallen in love is undisguisable, even to a purblind waiter, and they both looked wonderful.

Lois Bruce

We learn that Mr Bruce is the sort of man who is attracted to women in times of shortcoming, which may explain what has attracted him to Mrs Sheridan. The same thing had attracted him to his own wife, and we know that Lois is his second wife because Mrs Sheridan has told him that she had known of his first wife (Martha Chase) at university. We deduce that he is the sort of man who plays with saviour fantasies in his romantic relationships, but once he’s ‘fixed’ a woman, he moves on to the next one:

Lois had been frail when Mr. Bruce first met her. It had been one of her great charms. … “I forgot to tell you that Aunt Helen called on Wednesday. She’s moving from Gray’s Hill to a house nearer the shore.” He tried to find something to say to this item of news and couldn’t. After five years of marriage he seemed to have been left with nothing to say.

We are given an entire, lengthy paragraph about Lois’s shopping on Fifth Avenue, which I think must be designed to bore the reader, in order to encourage the reader to understand why Mr Bruce might find his current wife equally boring. Unfortunately, this is exactly the sort of representation of women that gave Cheever a reputation for his dismissal attitude towards women in general. His narrator makes sure to say that her extreme interest in shopping applies to a great number of women, underscoring a stereotype about how women just love shopping:

Lois Bruce, like a great many women in New York, spent a formidable amount of time shopping along Fifth Avenue.

To further align the reader with Mr Bruce, Lois Bruce goes on and on about her ailments; first her back, then about how she hasn’t been able to taste anything all week. We feel less than sorry for her because after all she has been able to immerse herself in nothing more frivolous than shopping, buying up all manner of luxury items. When Lois compliments the cook on the soup only after seeing that her husband likes it, this small exchange tells us that she lives via her husband — not only via his bank balance, but via his very experiences. This is a woman who has subsumed herself within marriage.

The strife between them is the classic Mars and Venus stuff (women need attention; men don’t give enough attention), and she deals with this in a passive aggressive manner:

The ghosts of her injured sex thronged to her side when she slammed open the silver drawer and again when she poured his beer. She set the tray elaborately, in order to deepen her displeasure in doing it at all. She heaped cold meat and salad on her husband’s plate as if they were poisoned. Then she fixed her lipstick and carried the heavy tray into the dining room herself, in spite of her lame back.

But then we are let inside Lois Bruce’s head, which makes her into a slightly more sympathetic character. As it turns out she, too, has a bit of a saviour complex. Birds of a feather get together:

DURING the next two months, Lois Bruce heard from a number of sources that her husband had been seen with a Mrs. Sheridan. She confided to her mother that she was losing him and, at her mother’s insistence, employed a private detective. Lois was not vindictive; she didn’t want to trap or intimidate her husband; she had, actually, a feeling that this maneuver would somehow be his salvation.

THEME

So, do readers align ourselves with the unfaithful couple, or with Mr Sheridan and Lois? It’s a rule of thumb that readers will empathise with the viewpoint characters. Another rule of thumb is that readers will enjoy reading about characters who are a little mischievous, even devious, as Mr Bruce is when he’s trying to ‘catch’ Mrs Sheridan. (The Trickster Trope is an oldie but a goodie.) And the way Cheever writes Mr Sheridan, of whom we’ve only seen the back of an angry, red neck, and Lois, who is a self-absorbed, privileged whiner of a wife, further encourages audience identification with Mr Bruce and Mrs Sheridan. Perhaps Cheever is testing our alliances here. If we find ourselves empathising with a pair of faithless individuals, what does that say about us, as fallible human beings?

Racial segregation exists in the backdrop to this story. Is Cheever asking readers to pick sides by endowing the romantic leads such different opinions on this matter? Which side are you on, boys? Is the title significant to this part of the story? Unlike when driving a car, when you’re on a bus you have to go where you’re taken, either by the driver or by the culture. The cloistered, white, upper-middle class world of the Sheridans and the Bruces cannot and will not continue as it has these last few decades. Perhaps the end of two marriages symbolise change in the wider world.

That they are aware of their affliction is everywhere made clear. In a story called “The Bus to St. James” a man watches his daughter in dancing school: “… It struck him that he and the company that crowded around him were all cut out of the same cloth. They were bewildered and confused in principle, too selfish or too unlucky to abide by the forms that guarantee the permanence of a society, as their fathers and mothers had done. Instead, they put the burden of order onto their children and filled their days with specious rites and ceremonies.”

Encounters with American Culture: Volume 2 (1973-1985) By Peter S. Prescott

THE APPLE NEVER FALLS FAR FROM THE TREE

I can see the influence on Matt Weiner, creator of Mad Men, in the following scene from this story:

“Oh, and I forgot to tell youthere’s been some trouble,” she said crossly. “Katherine spent the afternoon with Helen Woodruff and some other children. There were some boys. When the maid went into the playroom to call them for supper, she found them all undressed. Mrs. Woodruff was very upset and I told her you’d call.”

When Sally Draper is caught masturbating by Betty, it follows a scene in which Betty has been doing the same thing, only seemingly without realising it, against the washing machine. When Sally catches her father in flagrante delicto with his neighbour this precedes Sally’s foray into boarding school trouble, and eventually, on a station platform, Don Draper tells his daughter that she is exactly like her parents and will never be able to get away from that fact.

The comparison continues with the symbolism of the rats in a cage, which Mr Bruce smells when he enters his daughter’s room.

This is Cheever’s central theme (as it is Fitzgerald’s in The Great Gatsby): those who are busy climbing ladders, or digging in their heels on the top rungs of those ladders, leave it to others to pick up afterwards — to the maids, for instance, in “The Bus to St. James,” who pick up the peanuts from the rug.

The Call of Stories: Teaching and the Moral Imagination By Robert Coles

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

SHIFTING POV

More than in his previous stories, Cheever switches point of view in this story, using a mixture of close-third person (first aligned to Mr Bruce and then to Mrs Sheridan), then moving the camera in and out of their heads, sometimes to view the couple from the edge of a cafe, as a casual observer:

One of her daughters had a mild case of measles, she said, and [INSIDE BRUCE’S HEAD] Mr. Bruce was interested in the symptoms. But he looked [OUTSIDE BRUCE’S HEAD], for a man who claimed to be interested in childhood diseases, bilious and vulpine. His color was bad. He scowled and rubbed his forehead as if he suffered from a headache. He repeatedly wet his lips and crossed and recrossed his legs. Presently, his uneasiness seemed to cross the table. During the rest of the time they sat there, the conversation was about commonplace subjects, but an emotion for which they seemed to have no words colored the talk and darkened and enlarged its shapes. She did not finish her dessert. She let her coffee get cold. For a while, neither of them spoke. [OBSERVING THE COUPLE FROM ACROSS THE CAFE] A stranger, noticing them in the restaurant, might have thought that they were a pair of old friends who had met to discuss a misfortune.

In writing groups, this is often referred to as ‘head-hopping’, and is seen as a bad thing, but it’s not. The reader is perfectly capable of dealing with this shift in point-of-view, providing it’s done seamlessly like this. If there is a dramatic shift in point of view (say from Mrs Sheridan to Mr Bruce) there will be a double carriage return, accompanied by a transitionary phrase such as:

MR. BRUCE returned to a much pleasanter home.

(thereby presenting us with a comparison).

WITHHOLDING SNIPPETS OF INFORMATION TO MAKE THE READER WONDER, BRIEFLY, WHAT’S HAPPENING

When Lois hires the private investigator to track down her husband, we see her leave the house and go around to someone’s apartment. Though we’re fairly sure she’s going to confront her husband, we’re not sure. I wondered briefly if she, herself, had a man on the side when she knocks on the door screaming, ‘Stephen!’ This is because we haven’t been told the given name of Mr Bruce. We soon find out that indeed this is her own husband she’s referring to, but because she yells, ‘Stephen Bruce!’ I’m in no doubt that Cheever knew exactly what he was doing. (He inserted the full name because he knew we’d be wondering who Stephen is.)

STORY SPECS

First published in The New Yorker, January 1956.

7,100 words

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

[Cheever’s] stories can be read as chronicles of how the struggle between good and evil impulses unfolds in the lives of people of varied temperaments and shortcomings — usually, though not always, amid the complex social rituals of upper middle-class American protestant society. Johnny Hake [sic — it was Francis Weed] in “The Country Husband,” Asa Bascomb in “The World Of Apples,” Mr. Bruce in “The Bus to St. James’s” — all these Cheever creations are involved in prurient escapades or exploitative behaviour, and it is Cheever’s gift to chart with great precision of language their experiences as they try to reconcile their actions and impulses with their consciences. In each of these stories, Cheever explores the tension between what he once referred to as our erotic nature and our social nature.

The Columbia Companion to the Twentieth-Century American Short Story edited by Blanche H. Gelfant, Lawrence Graver

WRITE YOUR OWN

Vince Gilligan did a similar thing to audiences — new on TV — when he created a morally upright citizen then turned Walt right around to expose him as a thoroughly nasty individual. This tested the audience, possibly even more than Gilligan himself could predict — and I now consider Breaking Bad to be somewhat of a barometer of a viewer’s misogyny. (A large proportion of viewers never lost empathy for Walter White at all, instead wishing the annoying but far more innocent wives dead instead — I met one such viewer in a doctor’s waiting room.)

Cheever has done a similar thing here (consciously or not?), though on a much smaller scale: He uses the usual writer tricks to foster empathy in Stephen Bruce then has him do bad things. He passes no moral judgement. We’ve seeing a lot of stories like this recently — we are now in the era of the antihero, especially in American TV.

When the book is finished I immediately lose interest in the characters. And I never make moral judgments. All I would say is that a person was droll, or gay, or, above all, a bore. Making judgments for or against my characters bores me enormously; it doesn’t interest me at all. The only morality for a novelist is the morality of his esthétique. I write the books, they come to an end, and that’s all that concerns me.

FRANÇOISE SAGAN

How can the antihero be put to good purpose? How can we create empathy in a morally corrupt character to lead the audience to some sort of empathy about human nature in general? Or about themselves?

See also: I have a character issue, by the actor who plays Skyler White, in the NYT