“The Bloody Chamber” is a feminist-leftie re-visioning of Bluebeard, written in the gothic tradition, set in a French castle with clear-cut goodies and baddies.

The title story of The Bloody Chamber, first published in 1979, was directly inspired by Charles Perrault’s fairy tales of 1697: his “Barbebleue” (Bluebeard) shapes Angela Carter’s retelling, as she lingers voluptuously on its sexual inferences, and springs a happy surprise in a masterly comic twist on the traditional happy ending. Within a spirited exposé of marriage as sadistic ritual, she shapes a bright parable of maternal love.

Marina Warner

The tale of Bluebeard’s Wife—the story of a young woman who discovers that her mysterious blue-bearded husband has murdered his former spouses—no longer squares with what most parents consider good bedtime reading for their children. But the story has remained alive for adults, allowing it to lead a rich subterranean existence in novels ranging from Jane Eyre to Lolita and in films as diverse as Hitchcock’s Notorious and Jane Campion’s The Piano.

description of a different book, Secrets Beyond the Door : The Story of Bluebeard and His Wives

The descriptions of setting are evocative and eerie; the reader knows something terrible is about to happen — it’s almost given away in the title, after all — what we don’t know is how the girl is going to escape. This is a fairytale for adults, utilising the contrivances and coincidences of the fairytale tradition to tell a story which is otherwise modern in resolution: There is no white knight in shining armour. Who is really the most likely to save a girl from harm?

In the 1970s, Angela Carter was translating Charles Perrault from French, and she compiled two volumes of fairy tales from all over the world for Virago. So there you have it: French language, fairy tale and feminist expertise in one writer, which is all evident in this story…

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE BLOODY CHAMBER”?

In France somewhere around the turn of the 20th Century, a 17-year-old girl is chosen to marry a wealthy Marquis. Immensely lonely, the unnamed narrator one day goes exploring her new castle while her husband is away on business only to find a torture chamber, housing the recently dead body of the Marquis’ recently deceased former wife. The Marquis returns, knowing that his new wife has discovered the torture chamber. (He gave her the keys, after all.)

In many Gothic romances, an older man brings a young wife into his family mansion. The imposing house contains a terrible secret, but the wife must promise not to explore it. In finally giving in to curiosity, she, however, acts according to the husband’s covert script, for he never intended the requirement of obedience to be fulfilled. His goal, Anne Williams explains, is to make her realize the extent of his wealth and power and to see her (reflected) place in it. The dead women in Bluebeard’s forbidden chamber, she argues, represent, “patriarchy’s secret, founding ‘truth’ about the female: woman as mortal, expendable matter/mater” (43). We are dealing here with what I call Bluebeard Gothic, a specific variant of the Gothic romance that uses the “Bluebeard” fairy tale as its key intertext. Many women authors have used it in order to explore patriarchal power structures. Examples include Margaret Atwood’s Lady Oracle, Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” and Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, to name a few.

He leads her down to the Bloody Chamber and is about to kill her when the narrator’s mother turns up, having galloped on horseback to save her daughter. She has intuited something wrong during a brief phone call. The mother, with a valiant background of her own, shoots the Marquis dead. A few postscript-sort-of paragraphs explain that the musically talented narrator inherited the castle, gave most of the wealth away, married the kind and blind piano tuner and started up a school of music.

STORYWORLD

TIME

The narrator makes reference to Paul Poiret (20 April 1879, Paris, France – 30 April 1944, Paris), who was a leading French fashion designer during the first two decades of the 20th century. This is one detail that tells us when the story was set. This is an era when ancient customs have not been forgotten by the aristocracy — strange customs linger ominously: ‘‘The maid will have changed our sheets already,’ he said. ‘We do not hang the bloody sheets out of the window to prove to the whole of Brittany you are a virgin, not in these civilized times.’ These were times when French women were expected to abide by ‘rules for hair’, long and flowing while a virgin, pinned up after marriage (cut shorter in middle age, close cropped for the elderly): ‘he would not let me take off my ruby choker, although it was growing very uncomfortable, nor fasten up my descending hair, the sign of a virginity so recently ruptured that still remained a wounded presence between us.’

PLACE

A young woman moving to an old house has been a staple of gothic literature ever since the first gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto, was published in 1764. Today that trope has unmoored itself a bit from being strictly gothic, with modern authors employing it to lend an air of nostalgia, romance, or intrigue to their stories. These three books probably couldn’t be more different, aside from the fact that they thrust their heroines into strange old houses and see what happens when the dust shakes off. After 250-ish years, it’s hard to say this isn’t a useful plot device!

A stand-out feature of this short story is the portrait of an ominous castle where you just know something terrible is happening. It is cold, but the cold juxtaposes with the odd image of warmth. The landscape is lonely, as is the narrator. (Notice also, the narrator describes herself as a flower):

As soon as my husband handed me down from the high step of the train, I smelled the amniotic salinity of the ocean. It was November; the trees, stunted by the Atlantic gales, were bare and the lonely halt was deserted but for his leather-gaitered chauffeur waiting meekly beside the sleek black motor car. It was cold; I drew my furs about me, a wrap of white and black, broad stripes of ermine and sable, with a collar from which my head rose like the calyx of a wildflower.

With the extended metaphor of the lily, even the sky is ‘streaked’ with the colours of flowers:

And we drove towards the widening dawn, that now streaked half the sky with a wintry bouquet of pink of roses, orange of tiger-lilies, as if my husband had ordered me a sky from a florist. The day broke around me like a cool dream.

The castle, in its misty blues, greens and purples, is the colour of the sea and as explained by the author, is almost of the sea itself. Although cut off from land by tide, it’s important that it be reachable by horse (for the plot to conclude successfully). Still, the half-day isolation exudes the feelings of solitude. Why does the narrator describe the castle as ‘amphibious’ (able to live/operate on both land and water)? At its most basic meaning ‘amphibious’ means ‘two-fold in nature’ or ‘duplicitous’, or ‘not what it seems’. A magnificent abode such as this nevertheless houses great sorrow.

And, ah! his castle. The faery solitude of the place; with its turrets of misty blue, its courtyard, its spiked gate, his castle that lay on the very bosom of the sea with seabirds mewing about its attics, the casements opening on to the green and purple, evanescent departures of the ocean, cut off by the tide from land for half a day … that castle, at home neither on the land nor on the water, a mysterious, amphibious place, contravening the materiality of both earth and the waves, with the melancholy of a mermaiden who perches on her rock and waits, endlessly, for a lover who had drowned far away, long ago. That lovely, sad, sea-siren of a place!

Later, the narrator finds the Bloody Chamber:

Not a narrow, dusty little passage at all; why had he lied to me? But an ill-lit one, certainly; the electricity, for some reason, did not extend here, so I retreated to the still-room and found a bundle of waxed tapers in a cupboard, stored there with matches to light the oak board at grand dinners. I put a match to my little taper and advanced with it in my hand, like a penitent, along the corridor hung with heavy, I think Venetian, tapestries. The flame picked out, here, the head of a man, there, the rich breast of a woman spilling through a rent in her dress—the Rape of the Sabines, perhaps? The naked swords and immolated horses suggested some grisly mythological subject. The corridor wound downwards; there was an almost imperceptible ramp to the thickly carpeted floor. The heavy hangings on the wall muffled my footsteps, even my breathing. For some reason, it grew very warm; the sweat sprang out in beads on my brow. I could no longer hear the sound of the sea.

Though set in modern(ish) times, this story is of the middle ages. So of course it is devoid of modern conveniences such as electricity. ‘Like a penitent’ puts the reader in mind of a religious ceremony, since religion cannot be disentangled from a time before separation of church and state. ‘Naked swords’ suggests vulnerability, though it is not the swords themselves that are vulnerable. The author points out that the objects ‘suggest some grisly mythological subject’. Notice the change in temperature; all around is cold, but here in the torture chamber there is only heat — the heat of hell, perhaps, but also to show the reader that this is another world, separate from the cold surrounding landscape. Things happen down here that would never happen up there.

As far as engaging all the senses, the above paragraph is a case-study in writing: We are given plenty of texture (the wall-hangings, the carpet) but rather than go through all of the five senses, including smell, as beginner writers are often told to do, a master writer such as Angela Carter is able to weave the senses in an almost synesthesic way: ‘The heavy hangings on the wall muffled my footsteps, even my breathing.’

CHARACTERS

The young chatelaine has grown up poor due to her mother marrying a poor soldier who then got killed in the war. But since the mother married down, she brings up her daughter with the middle to upper-class attitudes she herself harbours; this young woman is very knowledgeable about art and music, with a perfect musical ear. The mother spent everything she had on her daughter’s education. This explains how she was then able to marry up herself. Yet our narrator is not entirely naive — she is naive only in relation to her much older self. She knows that her husband’s business dealings in poppies are connected to dealings in opium. The marquis calls her ‘Saint Cecilia’ (the patroness of musicians) presumably because of her musical talents.

The Marquis ‘was rich as Croesus.’ He has a black beard and red lips — red and black symbolism of blood and death, drawing attention to the ‘snout’ area. He smells of leather — his cologne, his clothing, his books, his sofa. He has dead eyes. This creature is borderline supernatural. He is the werewolf/vampire of folklore.

His face was as still as ever I’d seen it, still as a pond iced thickly over, yet his lips, that always looked so strangely red and naked between the black fringes of his beard, now curved a little. He smiled; he welcomed his bride home.

The Marquis is surrounded by equally ominous characters. The chauffeur eyes the young bride ‘invidiously’ (invidious – tending to cause discontent, animosity, or envy). Even the housekeeper ‘had a bland, pale, impassive, dislikeable face beneath the impeccably starched white linen head-dress of the region. Her greeting, correct but lifeless, chilled me.‘ This feels like a house of ghosts, except for the blind piano-tuner, whose very blindness makes him innocent. He therefore is immune to corruption, unable to see the torture chamber, as other members of the household presumably can.

Less information is given about the mother, but at the end we realise we’ve been given more than enough. We know that this is a mother who will miss her daughter dearly:

[Mother] would linger over this torn ribbon and that faded photograph with all the half-joyous, half-sorrowful emotions of a woman on her daughter’s wedding day.

We also know that she has bravery and adventure in her past:

Are you sure you love him? There was a dress for her, too; black silk, with the dull, prismatic sheen of oil on water, finer than anything she’d worn since that adventurous girlhood in Indo-China, daughter of a rich tea planter. My eagle-featured, indomitable mother; what other student at the Conservatoire could boast that her mother had outfaced a junkful of Chinese pirates, nursed a village through a visitation of the plague, shot a man-eating tiger with her own hand and all before she was as old as I?

We are given this information near the beginning of the story and are almost encouraged to forget about it as, like the new bride, we are forced to confront immediate and present danger; the ominous intentions of the monstrous Marquis. Yet when the mother saves the day we are both surprised and not surprised.

IDEOLOGY

For me, a narrative is an argument stated in fictional terms.

Angela Carter

Angela Carter writes with a left-wing feminist ideology (which is why I enjoy her stories), and anyone who is moderately well-read in feminism will recognise phrases such as ‘And, as at the opera, when I had first seen my flesh in his eyes, I was aghast to feel myself stirring’ from books such as Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth, in which Wolf explains that women are acculturated to view women’s bodies as sexual objects just as men are, and therefore derive pleasure from sex by imagining themselves from their male partner’s point of view. The entire story is about the young women as sexual object, with the narrator herself cognisant of the fact that was an item to be purchased then consumed as a dish.

The narrator’s left-leaning politics are made apparent in the ending, when she gives most of the wealth away to the poor. She is uncomfortable with wealth made from others’ poverty and addictions.

As Frances Spufford points out, the original intended message for the Bluebeard story was that women shouldn’t be curious.

Astonishingly, the moral traditionally tacked on to the story was that curiosity is dangerous — as if Bluebeard’s murderous rage were the wife’s fault for looking inside the chamber. Can anyone really have believed that if she hadn’t, they would have lived happily ever after, the plot flipping over into Beauty and the Beast despite the butchery in the basement? Even more astonishingly, Bruno Bettelheim, concentration-camp survivor, effectively concurred. Leaping past the issue of who did what to whom in the chamber, and taking it as a symbol of forbidden knowledge in a general, sexual sense, he interpreted Bluebeard as a story about a woman’s infidelity and — twisting time strangely — her husband’s anger over it. Bettelheim’s moral: ‘Women, don’t give in to your sexual curiosity; men, don’t permit yourself to be carried away by your anger at being sexually betrayed.’

The Child That Books Built

The movement in the 1970s, of which Angela Carter was a big part, was in response to people like Bettelheim, still interpreting traditional tales in horribly sexist fashion. Bettelheim was an asshole who set psychology back a couple of decades. Look up his theories on the causes of autism. (tl;dr: Refrigerator Mothers)

STORYTELLING TECHNIQUE

Many of Carter’s figures and motifs appear in the Grimms’ collection of Children’s and Household Tales (1812–57). Carter was also a big fan of Edgar Allan Poe.

NARRATION

This first person narrator is retelling a story from a time when she was much younger: ‘My satin nightdress had just been shaken from its wrappings; it had slipped over my young girl’s pointed breasts and shoulders.’ So we know from the outset that she has survived the tale. She has also gained the insight that only comes with hindsight, which is a good technique to use when writing in the first person because it allows certain advantages of the third-person narrator. The story is written as a kind of confession/setting the record straight. The reader feels as if we are being let in on a community secret.

There is plenty of foreshadowing about the ominous, animalistic nature of the husband:

- I could see the dark, leonine shape of his head

- though he was a big man, he moved as softly as if all his shoes had soles of velvet, as if his footfall turned the carpet into snow. (He creeps around silently, as a dog can, with the coldness of a ghost.)

- there were streaks of pure silver in his dark mane.

The Romanian countess who died in the boating accident is also described by the narrator in animalistic terms: ‘The sharp muzzle of a pretty, witty, naughty monkey; such potent and bizarre charm, of a dark, bright, wild yet worldly thing whose natural habitat must have been some luxurious interior decorator’s jungle filled with potted palms and tame, squawking parakeets.’ Use of the word muzzle is particularly apt, since a muzzle can also refer to a device placed over the nose area to stop an animal from eating/biting etc.

Other vocabulary choices and images foreshadow an ominous event with hints of the supernatural:

- the ‘ribbon made up in rubies’ which ‘bites into‘ her neck (an animal metaphor so common you almost don’t notice it)

- the way the narrator’s new husband regards her as if ‘eyeing up horseflesh‘

- an eldritch half-light seeped into the railway carriage (eldritch – weird and sinister or ghostly)

- There is an uncomfortable overlap of sex and violence: ‘He lay beside me, felled like an oak, breathing stertorously, as if he had been fighting with me (stertorous – [of breathing] noisy and laboured.) ‘I had heard him shriek and blaspheme at the orgasm; I had bled.‘ Also: ‘There is a striking resemblance between the act of love and the ministrations of a torturer,’ opined my husband’s favourite poet.’

A truth about supernatural stories is that the reader must be sort of expecting it. No one likes to think they’re reading a realist story and suddenly have a ghost sprung on them. The genre has certain markers. For instance, the formal language. Rather than the equally correct ‘than me’ ending a sentence, the author chooses ‘than I’. Is this story truly supernatural? Was the phone call enough, or is there some telepathy involved? The way sparks seem to fly out of the opal ring at certain times makes this feel like a supernatural story to me. I get the feeling the castle is peopled mainly by ghosts.

In this way, Angela Carter makes use of fairytale techniques. When you read the Grimms’ version of fairytales you’ll find disturbing analogies about girls and women compared to food, and oftentimes eaten. Here too we have, ‘He stripped me, gourmand that he was, as if he were stripping the leaves off an artichoke’. Carter underscores this by comparing food itself to a woman, using a word reserved for women ‘voluptuous’: ‘A Mexican dish of pheasant with hazelnuts and chocolate; salad; white, voluptuous cheese‘

The arum lily has wonderfully ominous uses in fiction because all parts of the plants are poisonous, containing significant amounts of calcium oxalate as raphides. Not only that, the arum lily is not closely related to the real lily (lilium), and has an aura of ‘imposter’ about it — a signal that not all is as it appears.

In another short story ‘The Garden Party’ by Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield writes ‘People of that class are so impressed by arum lilies.’ Again, the arum lily signifies something terrible is about to happen, despite the glorious setting of the party at the top of the hill. It’s handy that arum lilies are often used in funerals, too. Mansfield knew her flower symbolism. In her short story “Poison” she uses lilies of the valley — symbolically sweeter and more innocent, but also poisonous.

Angela Carter puts her own spin on the lily imagery however, as all original writers must: ‘…with the heavy pollen that powders your fingers as if you had dipped them in turmeric. The lilies I always associate with him; that are white. And stain you….My husband. My husband, who, with so much love, filled my bedroom with lilies until it looked like an embalming parlour. Those somnolent lilies, that wave their heavy heads, distributing their lush, insolent incense reminiscent of pampered flesh….But the last thing I remembered, before I slept, was the tall jar of lilies beside the bed, how the thick glass distorted their fat stems so they looked like arms, dismembered arms, drifting drowned in greenish water.’ It eventually becomes clear that the lily is a metaphor for the young narrator herself, with her white skin, sometimes due to fear: ‘In spite of my fear of him, that made me whiter than my wrap, I felt there emanate from him, at that moment, a stench of absolute despair, rank and ghastly, as if the lilies that surrounded him had all at once begun to fester…The mass of lilies that surrounded me exhaled, now, the odour of their withering. They looked like the trumpets of the angels of death.‘

SENTENCE FRAGMENTS

I gathered myself together, reached into the cloisonne cupboard beside the bed that concealed the telephone and addressed the mouthpiece. His agent in New York. Urgent.

Sentence fragments are used to convey information quickly, especially mundane information such as answering a telephone, but have the added effect of producing tension, especially when surrounded by longer sentences.

UNCOMFORTABLE JUXTAPOSITIONS

As in the TV series Six Feet Under and many other stories about death, the juxtapositions serve to highlight the difference between the living and the dead.

‘And this absence of the evidence of his real life began to impress me strangely; there must, I thought, be a great deal to conceal if he takes such pains to hide it.’

I looked at the precious little clock made from hypocritically innocent flowers long ago

Time was his servant, too; it would trap me, here, in a night that would last until he came back to me, like a black sun on a hopeless morning.

And still the bloodstain mocked the fresh water that spilled from the mouth of the leering dolphin. (Dolphins are usually thought to be smiling.)

WORD CHOICE

Unfamiliar myself with much gothic literature, I found myself looking up quite a few words:

- wagon-lit — a sleeping car on a continental railway

- reticule — A woman’s small handbag, originally netted and typically having a drawstring and decorated with embroidery or beading.

- marrons glacés — a confection, originating in southern France and northern Italy consisting of a chestnut candied in sugar syrup and glazed. Marrons glacés are an ingredient in many desserts and are also eaten on their own.

- vellum — Fine parchment made originally from the skin of a calf.

- Catherine de’ Medici was an Italian noblewoman who was Queen of France from 1547 until 1559, as the wife of King Henry II.

- pellucid — transparently clear

- parure — a set of jewels intended to be worn together

- immolated — killed or offered as a sacrifice, especially by burning

- sacerdotal — related to priests; priestly

- catafalque — a decorated wooden framework supporting the coffin of a distinguished person during a funeral or while lying in state.

- nacreous — relating to nacre, which is mother-of-pearl

- gendarmerie — a body of soldiers, especially in France, serving in an army group acting as armed police with authority over civilians.

- pentacle = pentagram, a five-pointed, star-shaped figure made by extending the sides of aregular pentagon until they meet, used as an occult symbol by the Pythagoreans and later philosophers, by magicians, etc.

- Iron maiden — I know these guys as a heavy metal band but an iron maiden is a torture device, probably just fictional, consisting of an iron cabinet with a hinged front and spike-covered interior, sufficiently tall to enclose a human being. Earlier the narrator thinks of herself as a ‘mermaiden‘ — a Middle English term for ‘mermaid’.

- to prefigure — to be an early indication or version of (something)

- scullion — a servant assigned the most menial kitchen tasks

- vassal — a person or country in a subordinate position to another

- lustratory — lustral, purificatory (I think this may be a very unusual word, or made up by the author)

- auto-da-fé — the burning of a heretic

- widow’s weeds — clothes worn by a widow during a period of mourning for her spouse (from the Old English “Waed” meaning “garment”)

- dolorous — feeling or expressing great sorrow or distress

- lisle — a fine, smooth cotton thread used especially for stockings

- centime — French for ‘cent’

- Nice turns of phrase such as, ‘He raised the sword and cut bright segments from the air with it‘ tells the reader that the air is thick with tension.

LITERARY REFERENCES

Frankenstein, Pandora’s Box, Cain and Abel, the Arthurian Tristan and Iseult story, Medusa, hypotext being Bluebeard

STORY SPECS

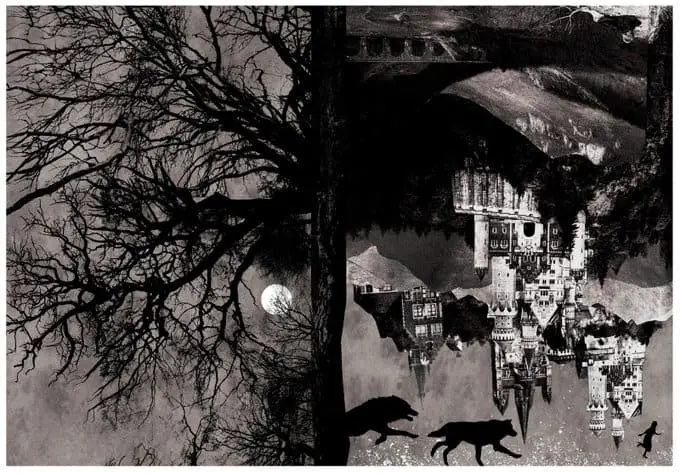

There have been many reprintings of this short story collection — some with retro looking covers straight out of the seventies, with the newer ones looking decidedly more modern with their darker palette and silhouette graphic design.

In 1979, the year that The Bloody Chamber was first published, Carter was not the first writer to tackle revisionist takes of fairy tales. Others, most notably Isak Dinisen (an acknowledged influence of Carter’s), Robert Coover and Anne Sexton, had published acclaimed retellings. What made The Bloody Chamber groundbreaking and singular, however, was the way it centred female sexuality and selfhood with an unapologetic, robust gusto, back when society wasn’t quite as commercially and critically embracing as it is now of feminist narratives. In a time when second-wave feminists were derided as bra-burning harpies, Carter’s openly gynocentric fiction was revelatory and iconoclastic.

Each of the stories is a re-visioning of a classic tale:

Contents

The Bloody Chamber — Bluebeard (Barbebleue, 1697) written down famously by Charles Perrault

The Courtship of Mr Lyon — Beauty and the Beast

The Tiger’s Bride — Beauty and the Beast

Puss-in-Boots — Carter hasn’t changed the name from earlier versions.

The Erl-King —The Erl-King takes his name from a folklore persona. An erlking is a mischievous sprite or elf that lures young people with the intent of killing them.

The Snow Child — Snow White

The Lady of the House of Love — which began as a radio play, Vampirella, for BBC Radio 3 in the summer of 1976 is about a beast of the courtly south who meets the ravenous wolf of more northerly folklore. The original Vampirella had a lot of footnote-like material about vampires. Because it was produced for radio, this explains why the voice speaks directly to the reader.

The Werewolf — Little Red Riding Hood (Le Petit Chaperon rouge)

The Company of Wolves — The Grandmother’s Tale, an oral fairytale related to later versions of Little Red Riding Hood

Wolf-Alice — Again, the beast of the courtly south meets the ravenous wolf of more northerly folklore

In The Company Of Wolves is a long short story, perhaps more of a novella, at 16,400 words.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

To get the very most out of “The Bloody Chamber”, apparently you’re best to read it alongside Carter’s essay The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography, which she published in 1979.

For a story with a similar plot, see Rebecca, a novel by Daphne du Maurier, which turns the typical Gothic relations of dominance upside down: the romantic hero turns out to be a masochist, while his wife is allotted the role of the beating woman.

Rebecca is also movie, and miniseries and like “The Bloody Chamber” is about a very young woman who marries an aristocratic, much older man whose previous wife has gone missing in mysterious circumstances, also a boating accident. Rebecca was first published in 1938, so shares a similar time period.

As the blind piano tuner says in the Angela Carter story, ‘I can scarcely believe it,’ he said, wondering. ‘That man … so rich; so well-born.’ That is what made Rebecca successful, though I feel the story is lost on modern audiences because its intrigue relies upon the reader’s incredulity that such a well-born person could do something so heinous. The modern audience knows that the rich (or especially the rich) do heinous things.

WRITE YOUR OWN

Horrible things tend to happen in magnificent castles. Likewise, lovely things happen in the most dire of accommodations. Is it possible to foreshadow happiness?

That wonderful header image is an illustration by Rebecca Whiteman, inspired by Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber”

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Angela Carter talks beauties and beasts with Terry Jones, BBC Arts