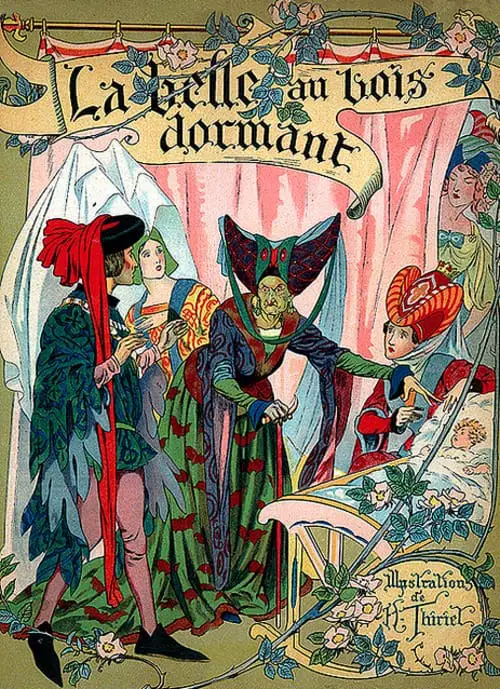

If you’ve already read Angela Carter’s short stories, in which she rewrites famous tales as feminist ones, you may well hear her scoffing silently in your head as you read these tales, mostly by Charles Perrault, who added his own paternalistic, misogynist morals as paragraphs at the ends. And if you’ve never read these tales by Perrault — and you may not have, because many different versions have been written since — it’s worth a look. This tale is quite different from any I read as a child. This is probably because modern tellers of this tale have simplified it.

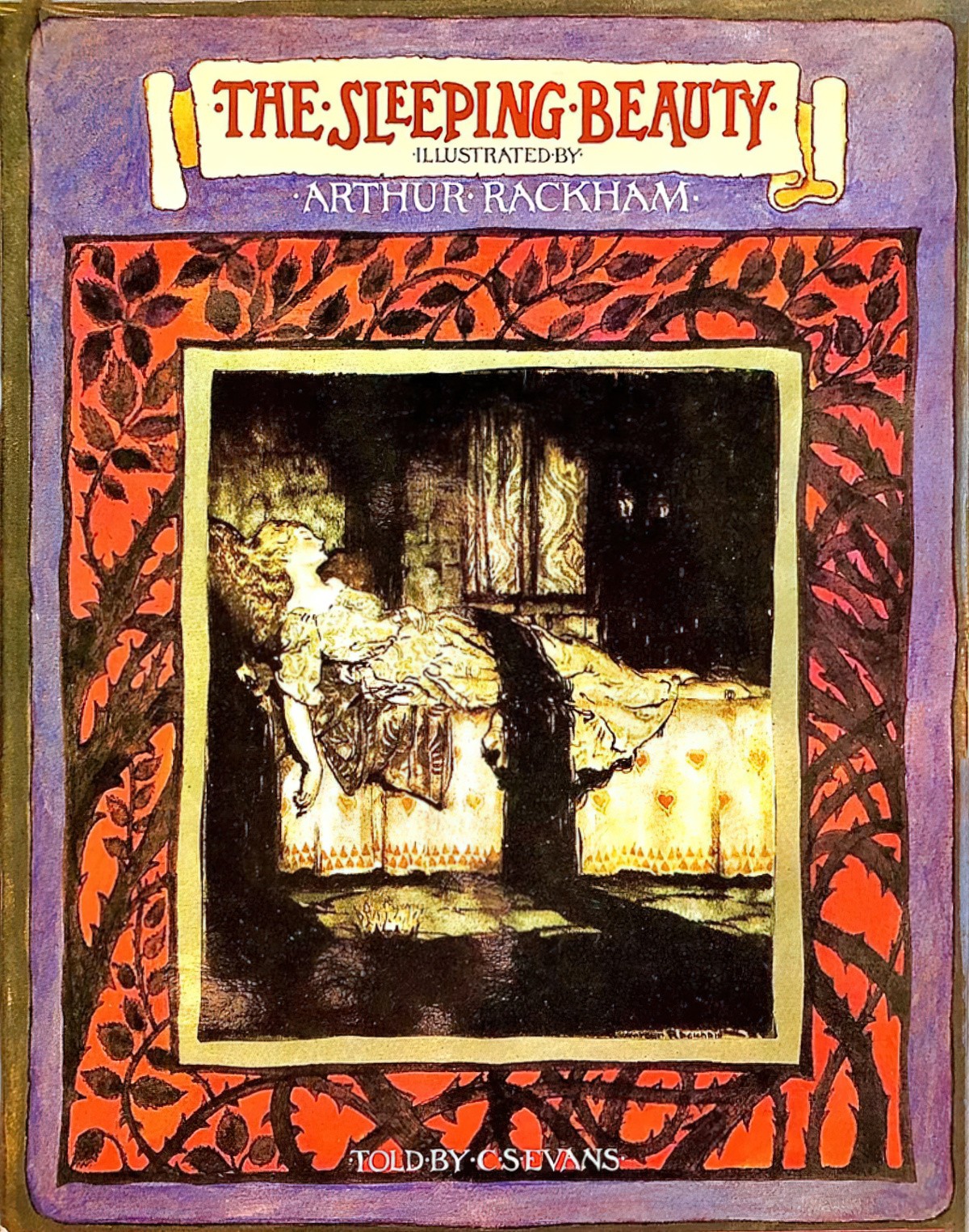

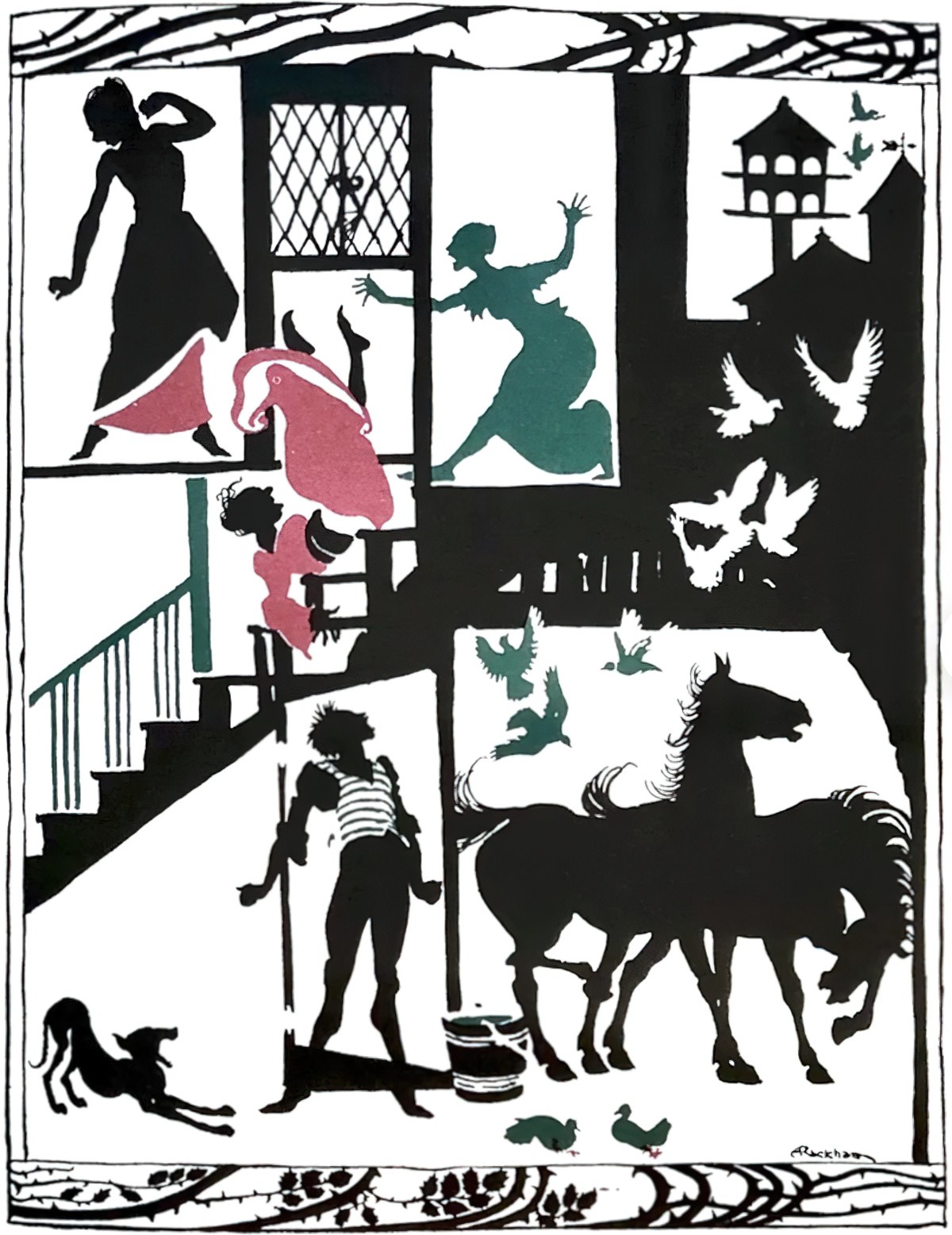

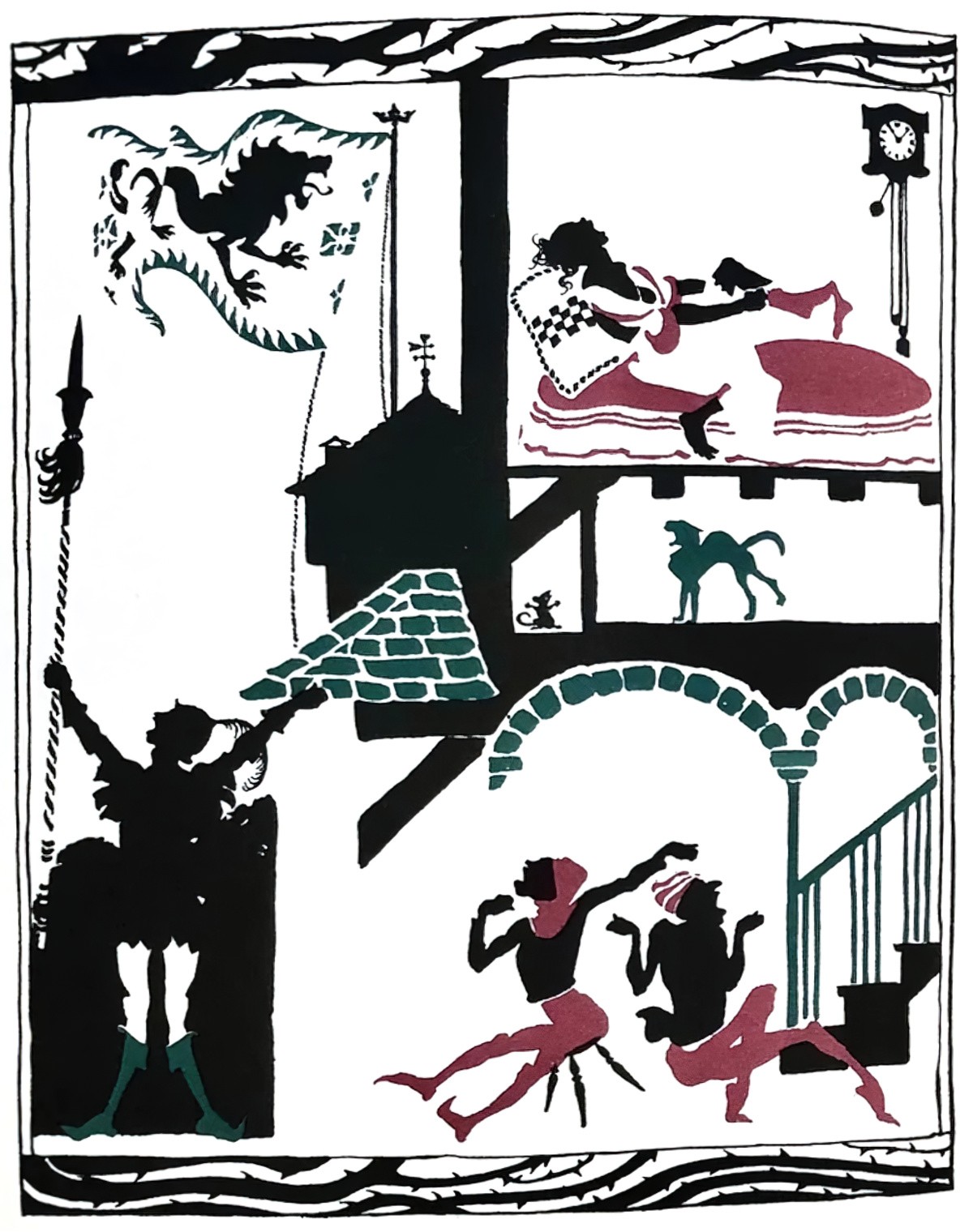

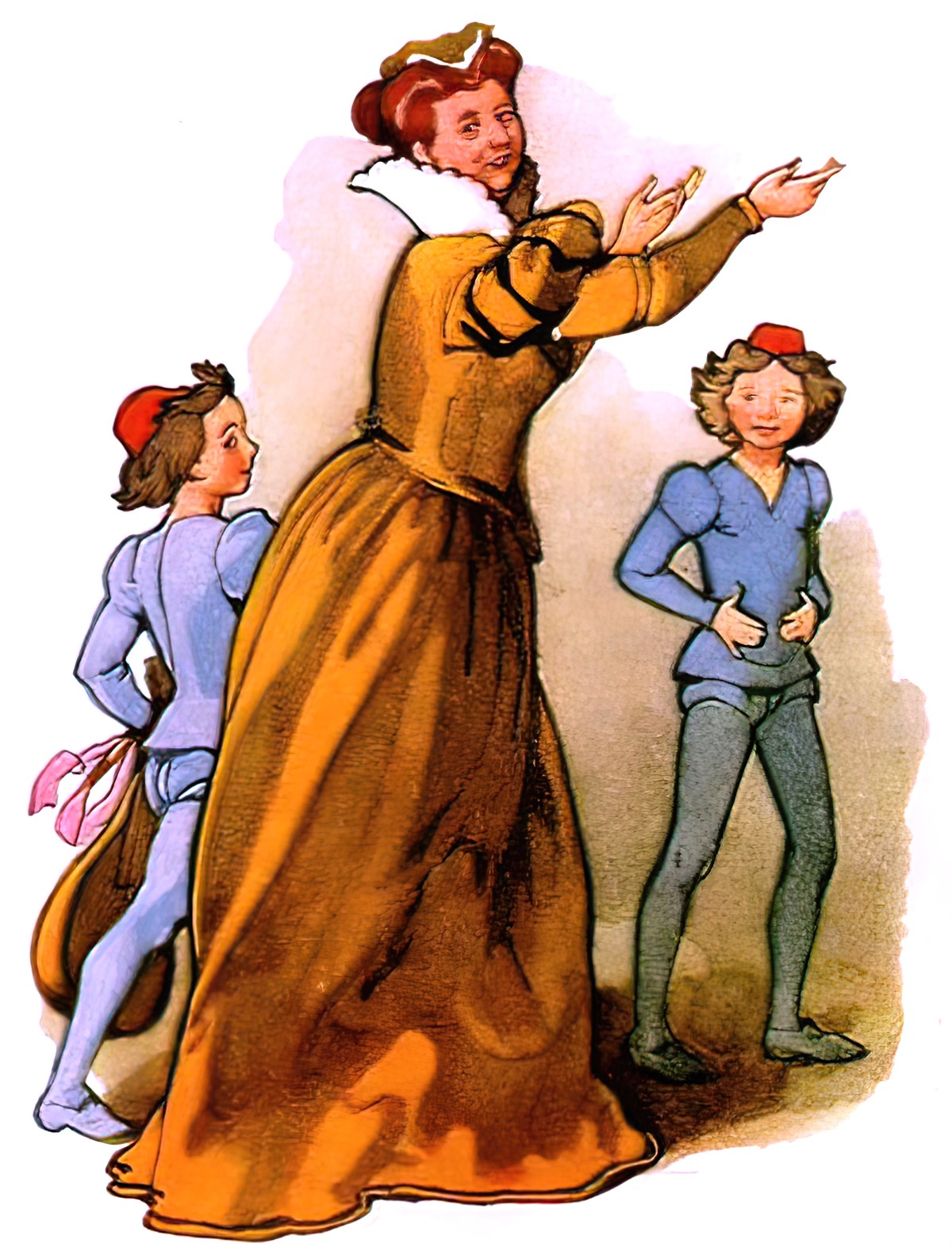

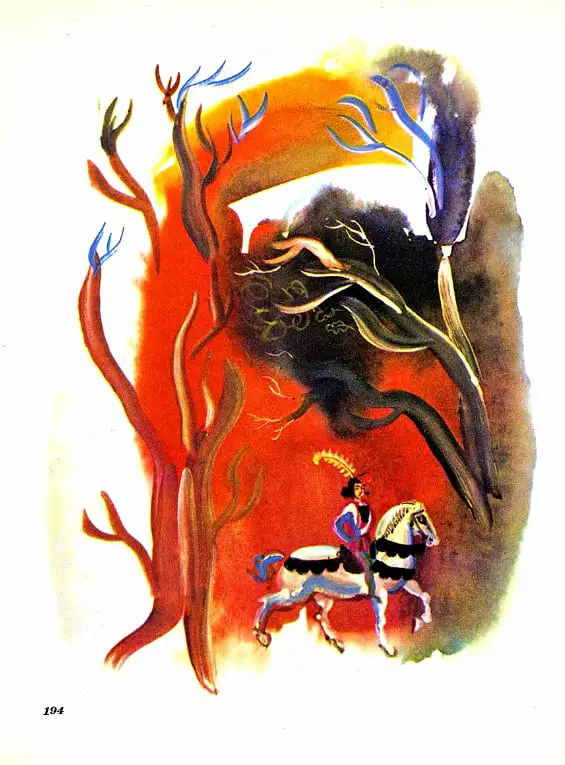

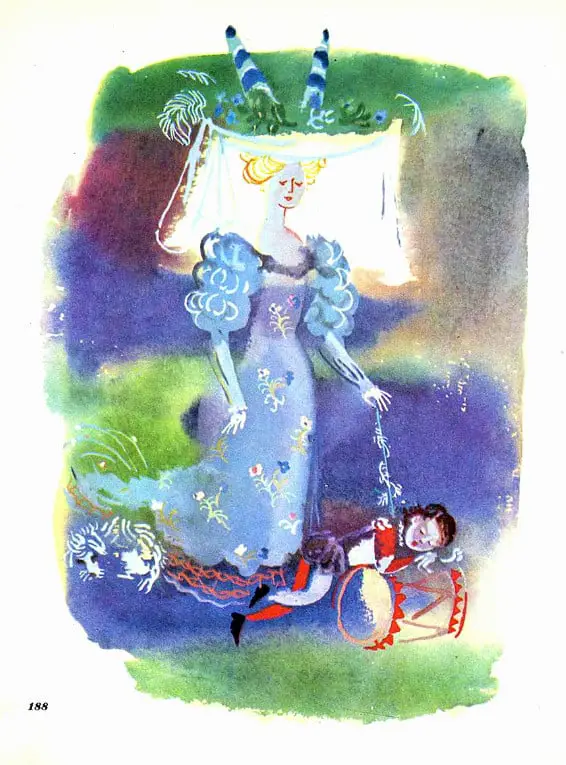

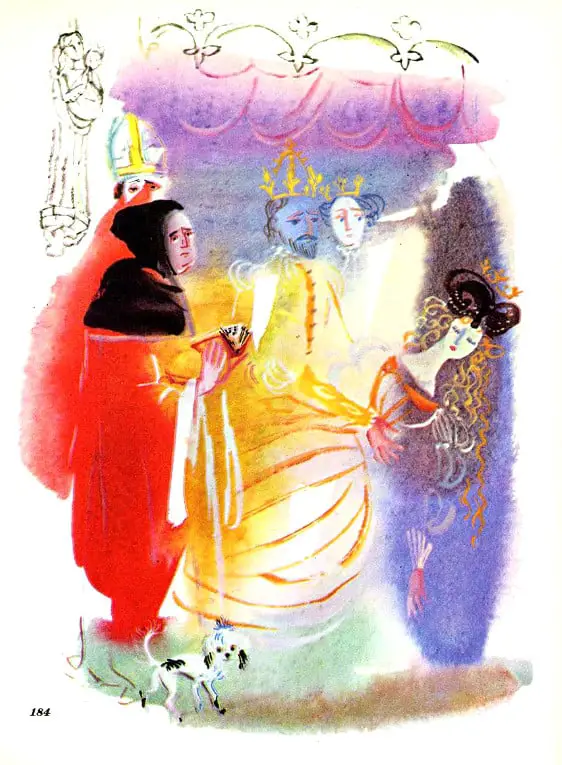

This 1982 collection of fairytales translated into English from French by Angela Carter is illustrated by Michael Foreman, who has had a prolific career since then. You may have seen his work in the books of Michael Morpurgo for instance. He’s been working from the 1960s through to now. It seems he can produce up to about 8 or 9 books per year — a phenomenal work rate, especially considering his painterly style.

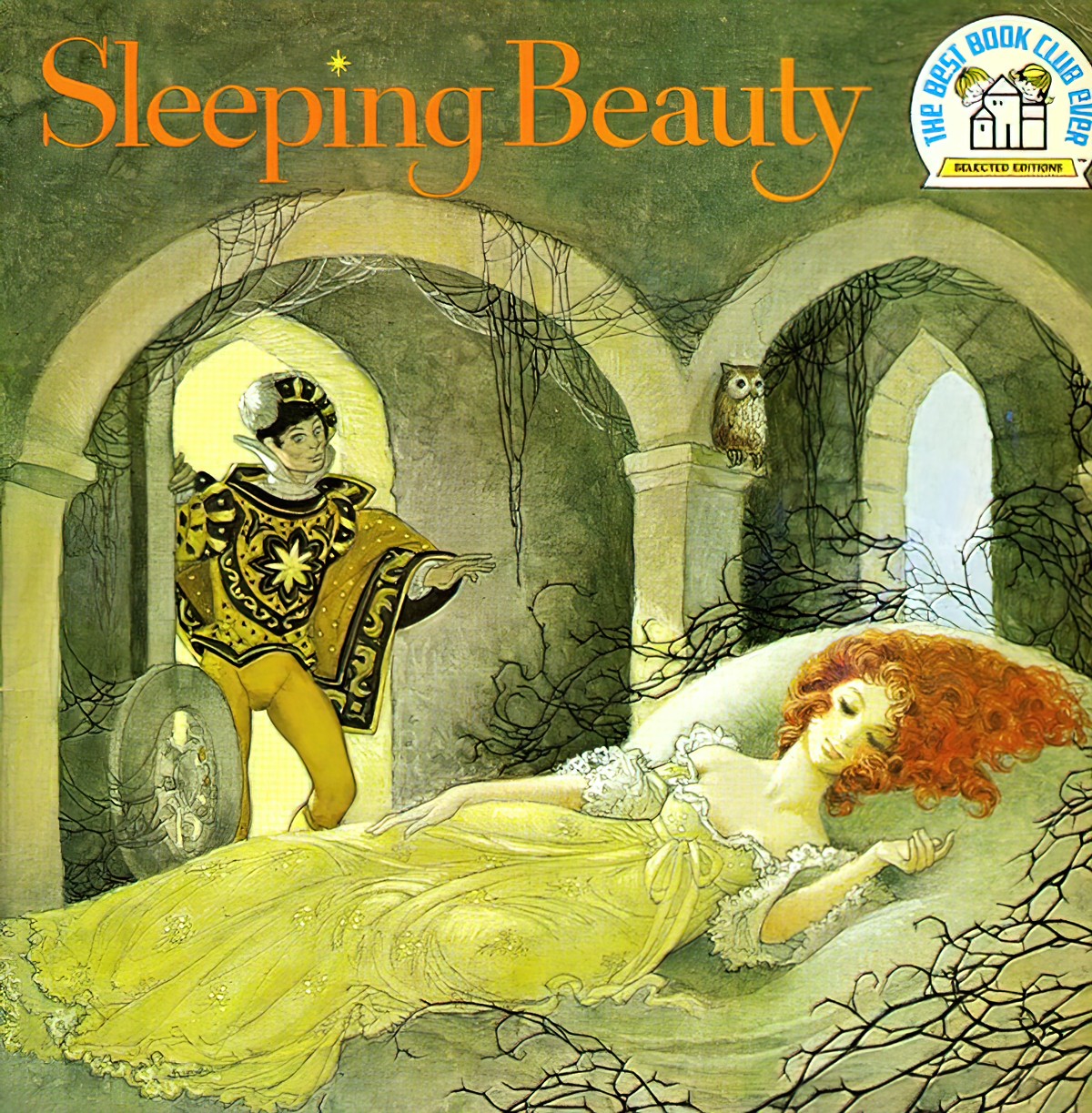

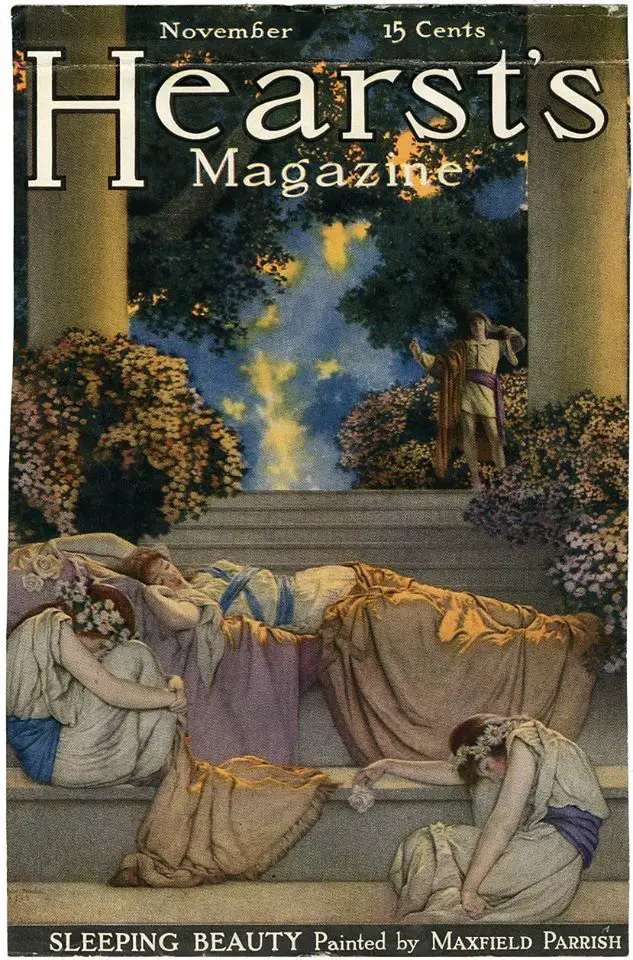

“Sleeping Beauty” is also known as “Briar Rose”.

If you’d like to hear “Sleeping Beauty” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Sleeping Beauty” was published April 2019.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PERRAULT’S TALE AND MODERN VERSIONS OF SLEEPING BEAUTY

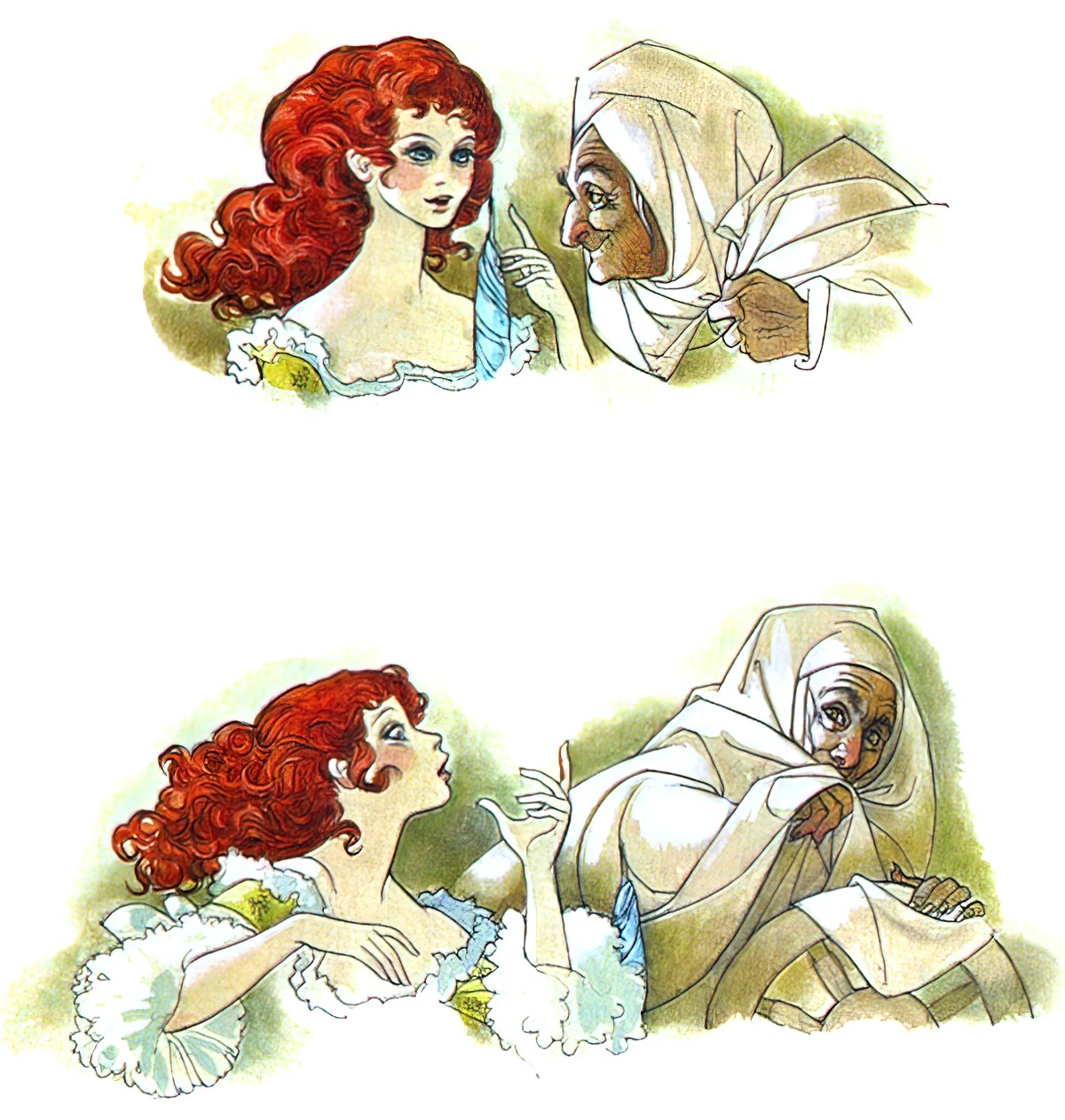

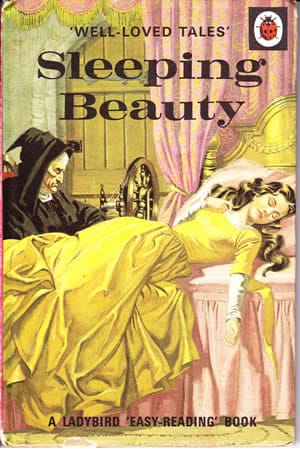

In Perrault’s version of Sleeping Beauty from the 1700s, there is not one but two wicked women — the version I remember from the childhood stories is one of the Ladybird Well-Loved Tales.

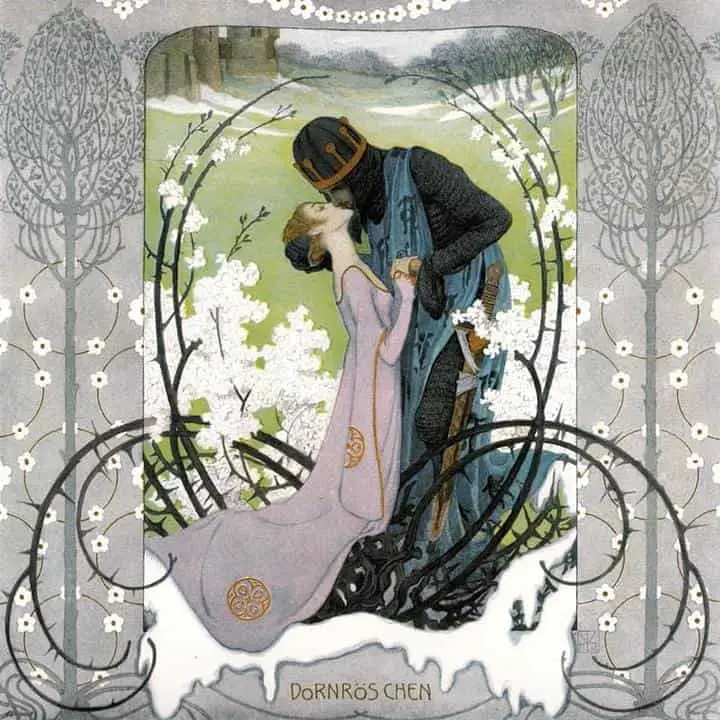

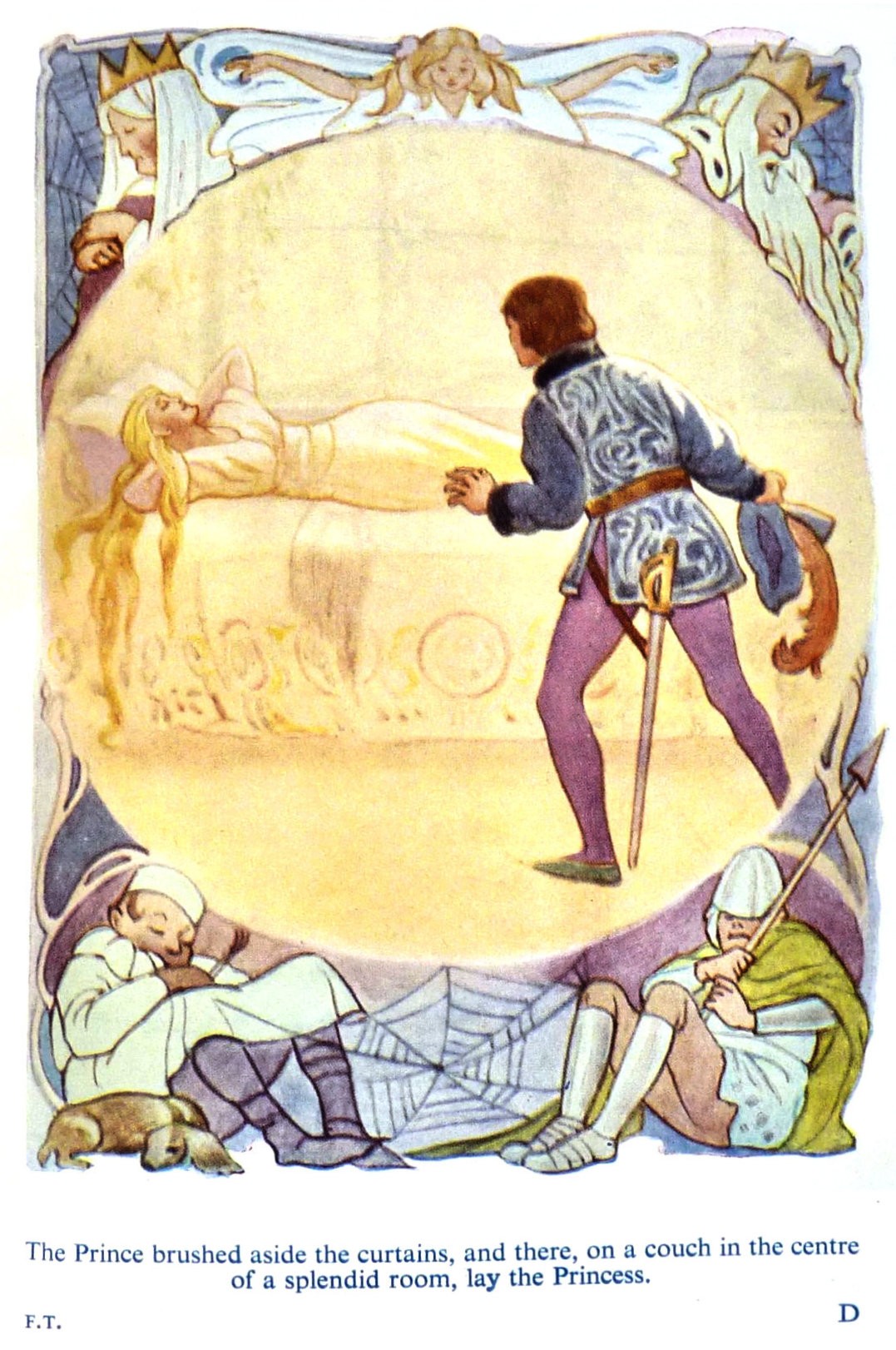

In this much simplified story from Ladybird there is no second ‘chapter’. The prince arrives, Beauty and Prince get married and they ‘live happily ever after’. In order to beef out the story a bit we have a succession of princes who try to get through the thick brambles that grow around the castle, but none of them is able to get through until the lucky dude who arrives at exactly the right time, at the 100 year point.

Both Sleeping Beauty and Snow White have been bowdlerised for modern children in a similar way, to the point where you might even get them a bit mixed up if you’re out somewhere and your kid asks you to recount a fairytale from memory. In modern adaptations of both stories Beauty is awakened by a passing Prince, she marries him and they live happily ever after. It’s all good.

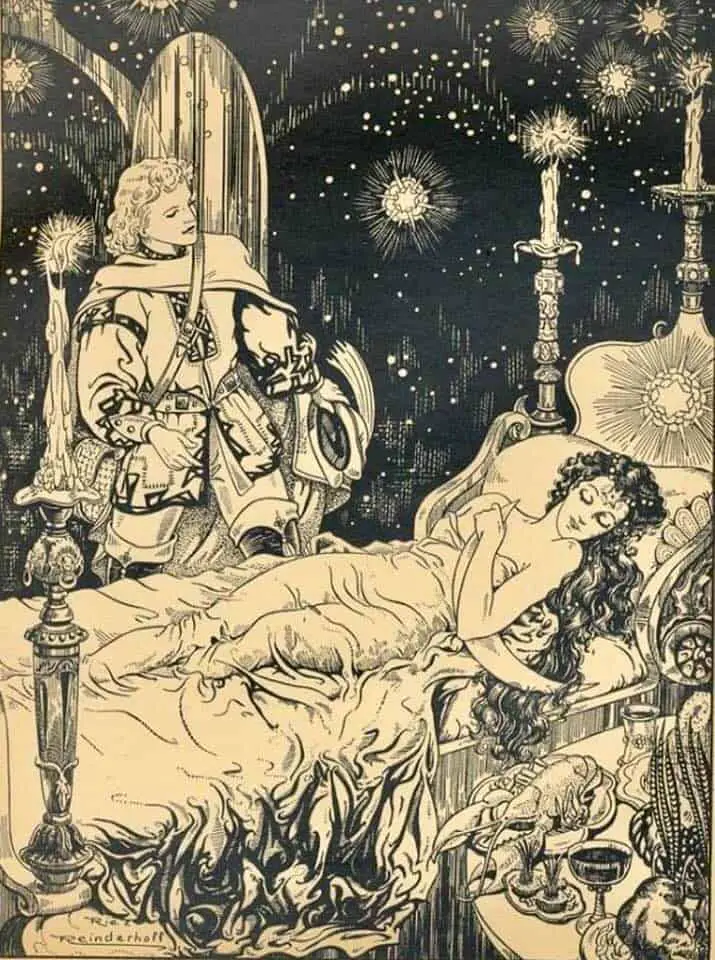

There is no happily ever after in the earlier version of Sleeping Beauty; nor is it a tale easily conflated with Snow White.

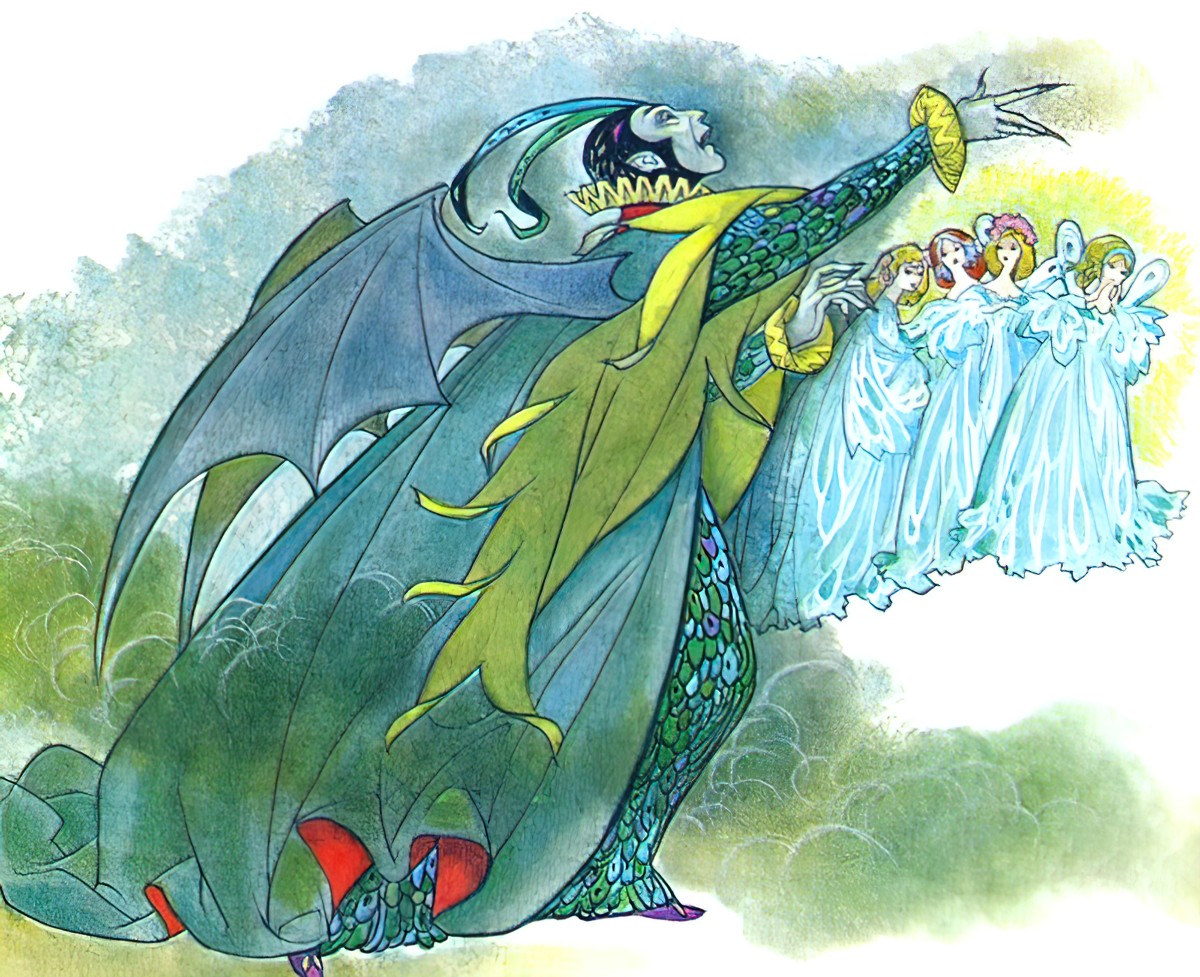

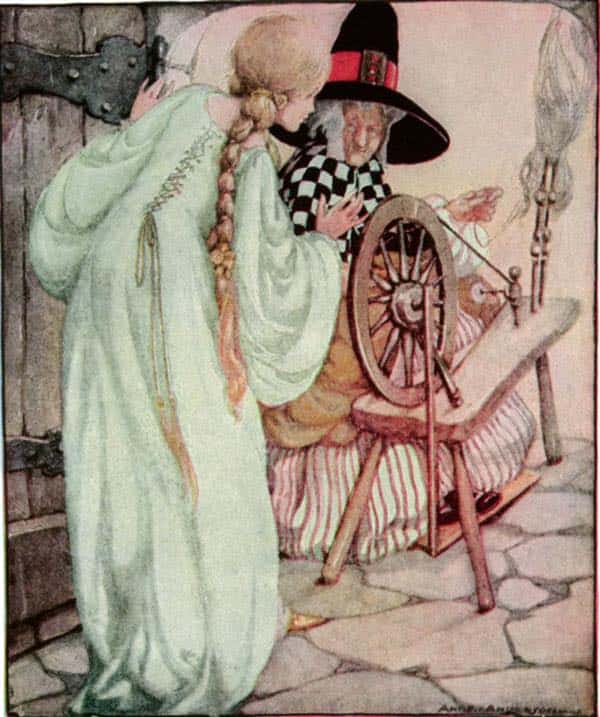

Illustrators vary in how they portray the fairies. In the Ladybird version above, the fairies all look like youthful Miss America finalists from the 1970s, with their long, blonde hair contrasting with the part witchy/part nunnery black costume of the old, evil fairy. Think a bit harder about what this says about women’s worth in general: Women are only ‘good’ if they are sexually alluring. An old woman dressed in a cross between a witch’s costume and a habit is as far away from sexual as you could possibly get. Therefore, we are to assume, she is no good. It’s therefore a slight feminist improvement that the most recent adaptations of Sleeping Beauty tend to feature ‘Tinkerbell’ type fairies rather than this Ladybird woman from the 1970s.

Perrault’s version of Sleeping Beauty isn’t even the worst one. It seems he sanitised it his own self.

Still older versions of the same tale type, among them “Sun, Moon, and Talia“, replace the prince with an already married king. In these versions, he rapes the princess while she lies sleeping and she gives birth to twins before waking up when one of the babies sucks the splinter out of her finger. The cannibalistic queen in this case is the king’s wife. Compare “The Brown Bear of the Green Glen“.

TV Tropes, Sleeping Beauty entry

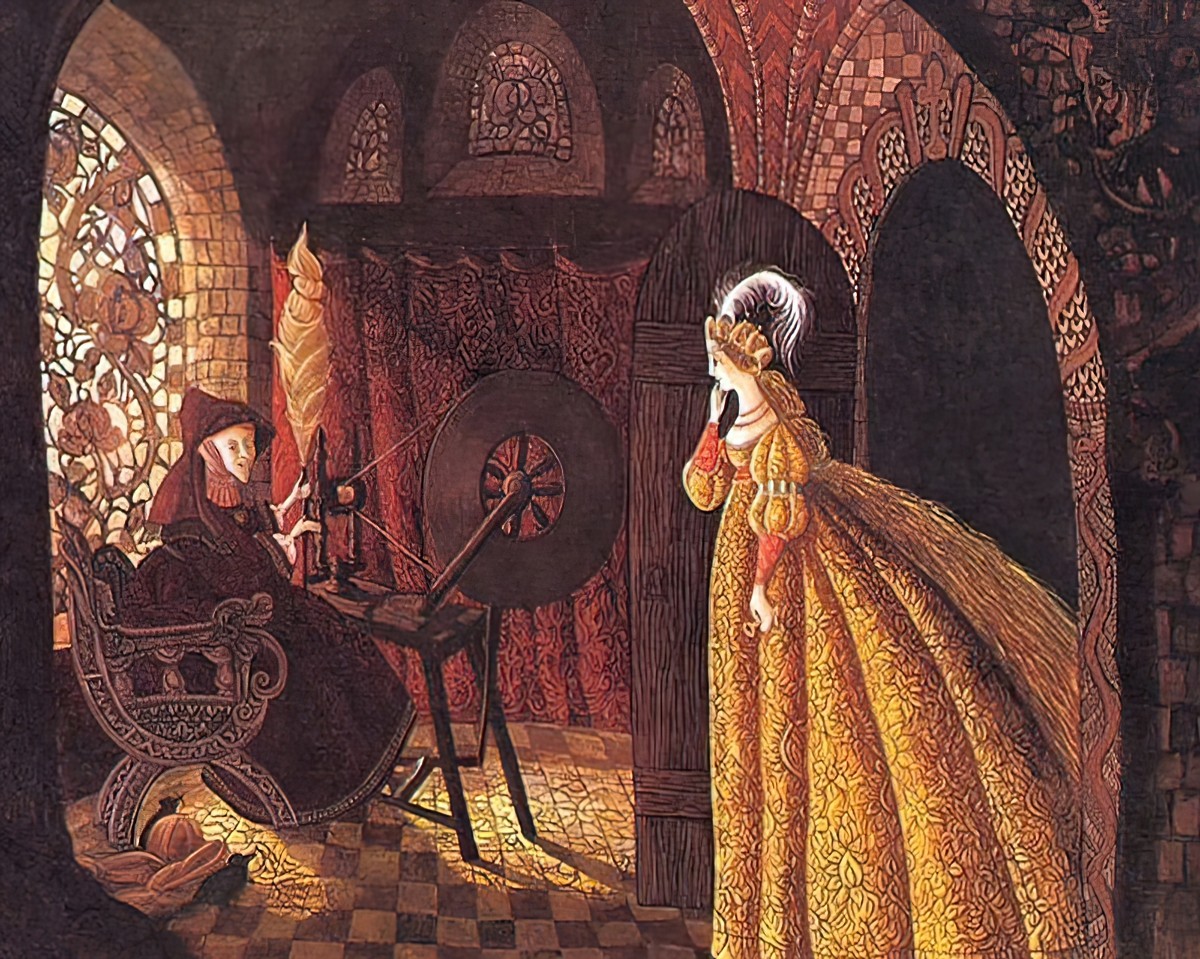

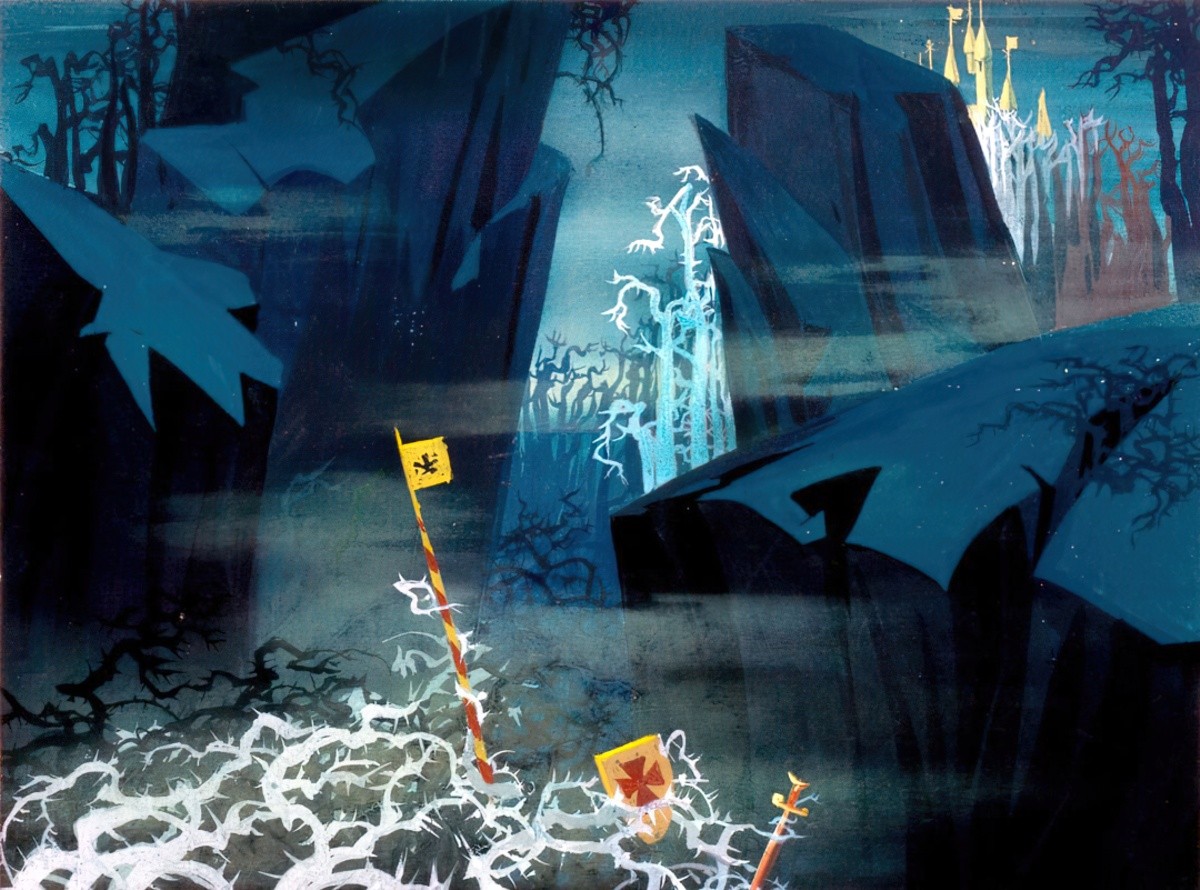

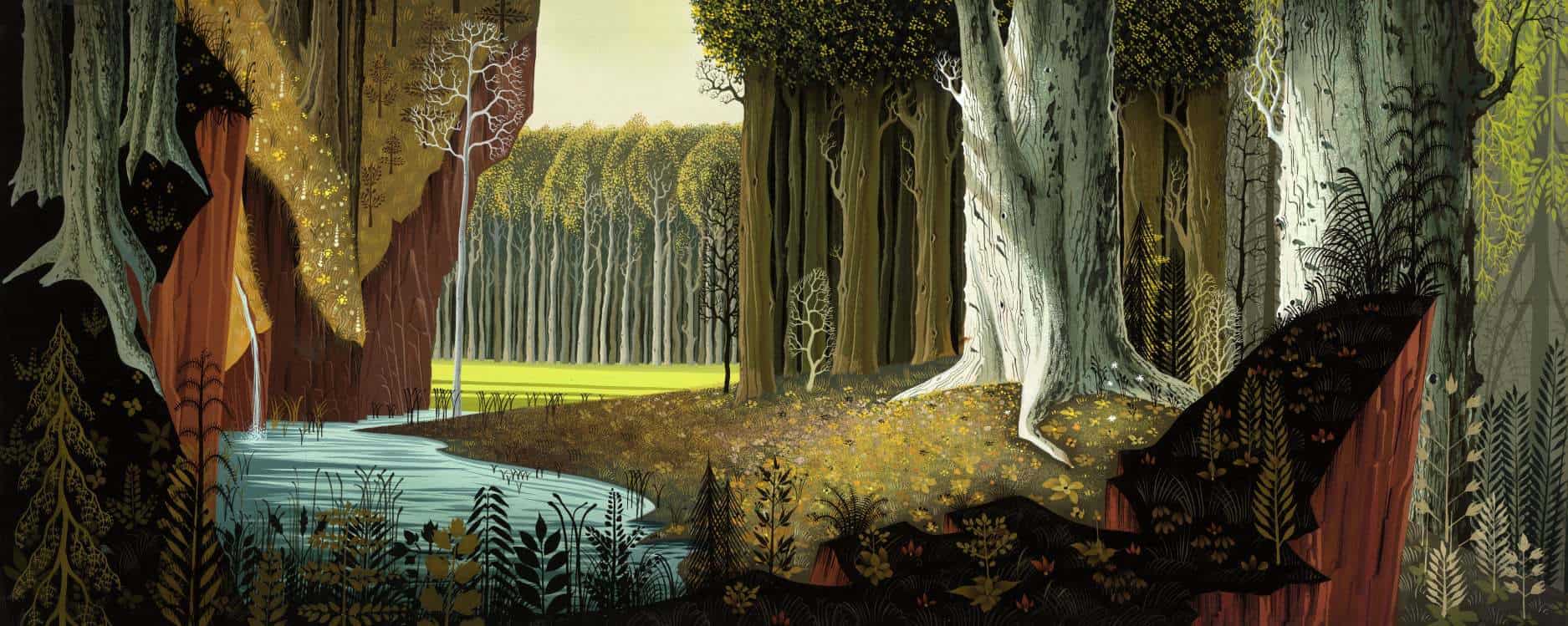

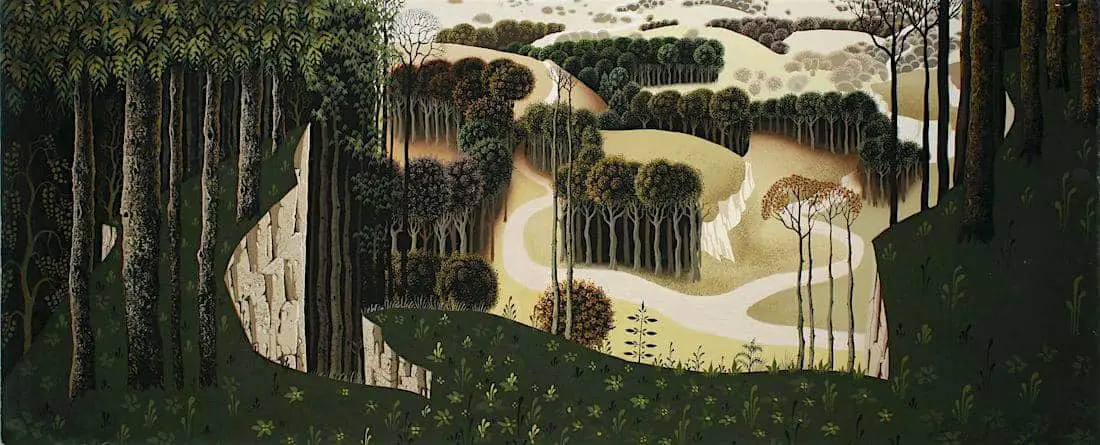

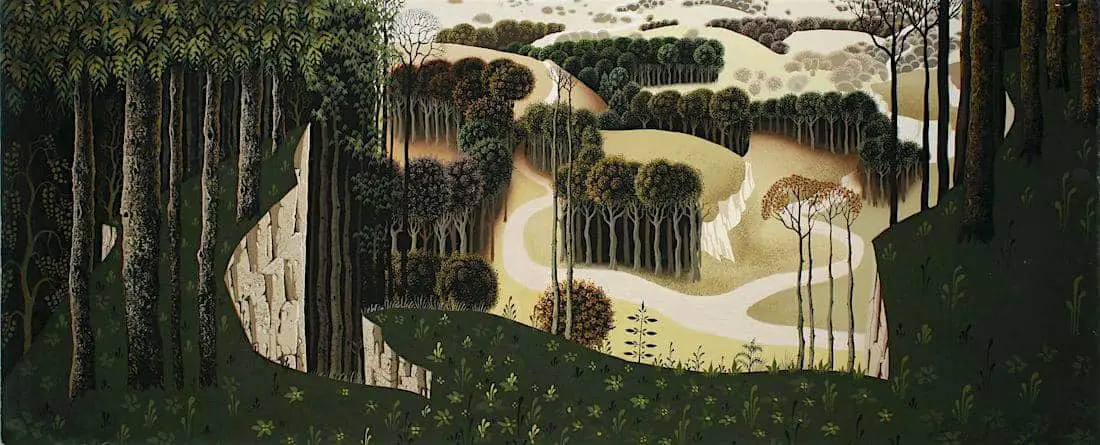

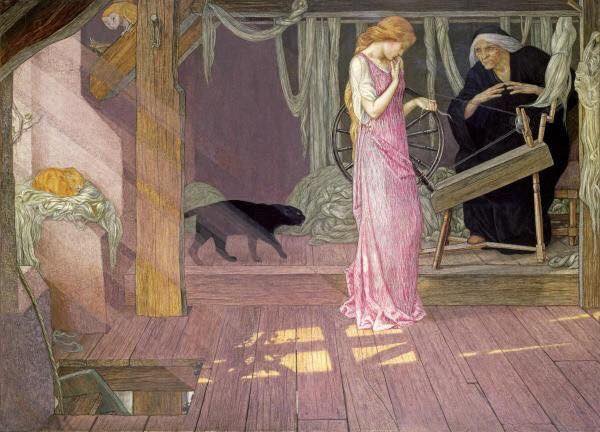

Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty” describes the enchanted castle in Gothic terms: blood-chilling and full of death. A frequent element of gothic novels is the heroine who falls into a death-like state. The links between death and sleep appear in many gothic works, not just in this very well-known tale. They tend to feature entrapment and towers.

CHARACTERS IN SLEEPING BEAUTY

In Perrault’s version we have not one but two evil women: first the evil fairy, next the evil mother-in-law. The girl never sees her own parents again, for although they’ve made all their staff and attendants fall asleep so she will be well looked after when she awakes, the bereaved parents leave their castle forever and go somewhere far away. There are two distinct parts to Perrault’s version, translated by Angela Carter in 1982. Honestly, it’s not ‘going-to-sleep’ book, as the title may seem to imply. This is a young adult tale, designed to warn young women not to rush into marriage. Now, it baffles me how Charles Perrault drew this particular moral from the tale, considering the girl in question had already been asleep and dreaming of this prince for 100 years!

Sleeping Beauty’s transgression is that she attempts to spin when it’s actually beneath her social class to do so. Spinning kept peasant women alive but will kill her.

STORY STRUCTURE OF SLEEPING BEAUTY IN THE WOODS

Whose story is this? While the title tells us the tale is about ‘Sleeping Beauty’, the girl is only a plot tool of a character. She has zero agency. At first I thought this was a story about the girl, but when I try to fill out the story structure it becomes obvious that actually the main character in this story is her evil mother-in-law. The whole thing about the evil fairy, that’s what Hitchcock would have called a MacGuffin: an event to get the story going. In the end, we don’t even think about what happened to that evil fairy.

WEAKNESS

The mother of the prince — I assume — feels usurped by the beautiful new daughter in law and is envious of the time her beloved son now spends with her.

DESIRE

She wishes her daughter-in-law gone and her son back.

OPPONENT

Sleeping Beauty, whose very beauty and privilege of birth mean she has lost her own boy forever.

PLAN

She will first eat her two grandchildren and then she will eat her daughter-in-law. (She is part ogre.) But her plans change once she realises the son’s wife and children are not dead at all, that they have been hidden in the cellar by a sympathetic servant man. Now she plans to kill Beauty in the most heinous way herself. She orders a huge vat to be brought into the courtyard, filled with horrible creatures. She’ll have the daughter-in-law and her children thrown into it.

BIG STRUGGLE

This part is much truncated and rather unsatisfying in Perrault’s version. All we know is that the king comes back early from faraway. He gallops into the courtyard and presumably there is some sort of showdown that the reader doesn’t get to read about. The evil queen rather impetuously, I feel, throws her own self into the vat of vipers instead.

ANAGNORISIS

The anagnorises of Perrault’s tale are actually ‘reader revelations’ and they come by way of the ‘Moral’ tacked onto the end of each transliteration. Don’t rush into marriage or you’ll end up with a mother-in-law who wants to eat you, is what Perrault gets from the story.

NEW SITUATION

“The king could not help grieving a little; after all, she was his mother. But his beautiful wife and children soon made him happy again.”

RESONANCE

The tale was cemented in contemporary popular imagination when adapted for big screen by Walt Disney Productions.

SLEEPING BEAUTY AND CANNIBALISM

Strangely enough, the cannibalistic nana has been left out of modern versions for kids. But look around at other fairytales and you’ll find that kid-munching mummies aren’t all that rare. These tales date from much earlier eras in which famines were common, and mothers did occasionally eat their own children:

George Devereaux, citing “Multatuli (1868),” pseudonym of novelist Edward Douwes Dekker, reports that during medieval famines and “even during the great postrevolutionary famine in Russia” the “actual eating of one’s children or the marketing of their flesh” occurred. He concludes that “the eating of children in times of food shortage is far from rare.”

Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

But Maria Tatar argues that although mothers did eat their children, it was generally only due to mental derangement caused by their own starvation. In medical/legal documents it was always a baby who was eaten rather than an older child. The child eating mothers of yesteryear are therefore mostly a myth, but have captured the public imagination and been incorporated into oft-shared tales, much like an urban legend of today. (Urban legends often have their origins in plot points taken from real-life heinous crimes which have been sensationalised by the media.)

Maleficent promised to be excellent, as a dive into the backstory of that evil fairy. But the 2014 film did not get good critical reviews. When will filmmakers understand that when you change the best known version of a well-loved tale too much you’re going to run into strife? The other problem for filmmakers though: Which version do you take as the ‘true’ version of the tale? Fairytales change so much, it’s not surprising they make huge alterations themselves in the name of original art.

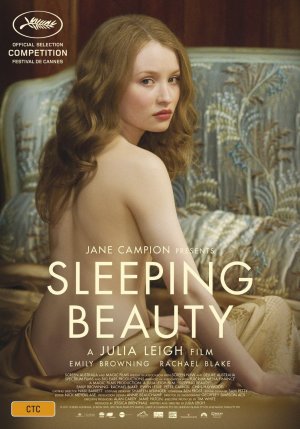

In 2011, Australia produced a film called Sleeping Beauty — a rather disturbing look into a certain kind of sex work. (The girl is drugged unconscious and used by men with a certain kind of fetish.)

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Sleeping Beauties: Transformation and Codification from Karen Healey

Sleeping Beauty, zombified and turned into a comic from Mary Sue

Angela Carter utilised Perrault’s Sleeping Beauty in her radio play Vampirella and in its prose variation The Lady of the House of Love.

…she felt as if she had become the heroine of “The Sleeping Beauty” and this feeling started manifesting itself in her daily behaviour.

a documented case of someone hallucinating a fairytale

The ‘Forced Sleep Trope’ is used in many different modern stories, in which a character is forced to fall asleep by means of a spell or magic potion. This can get very dark in stories about date rape and so on.

Review: ‘Sleeping Beauty’ Rests Uncomfortably and Unsuccessfully Between Nightmare And Wet Dream, from Film School Rejects

Short Film Of The Day: Granny O’Grimm’s Sleeping Beauty from Film School Rejects

Also check out the Japanese version of Sleeping Beauty, directed by Kihachirō Kawamoto, married Bunraku sensibility with Czech puppetry. This adaptation was co-produced with the Jiří Trnka Studio in Prague. It’s in Japanese without subtitles, but the puppetry alone will give you a creepy vibe.

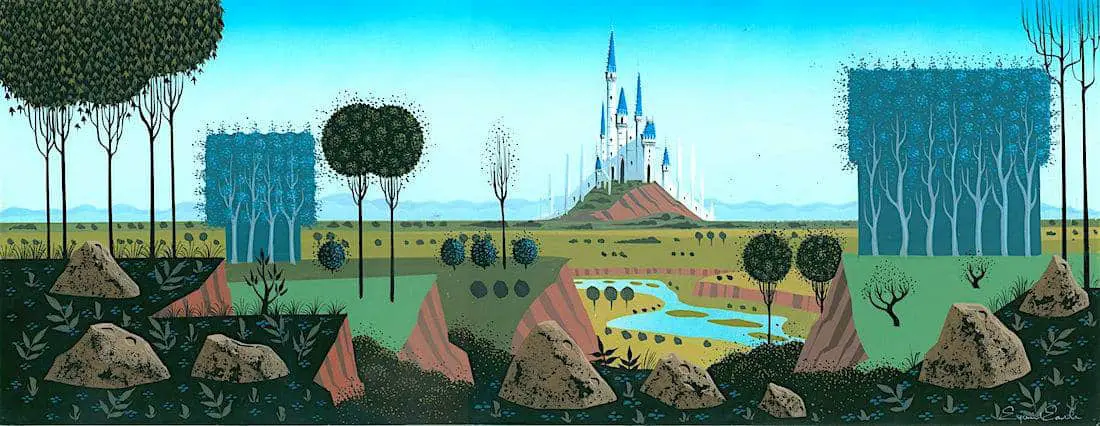

Header image: Eyvind Eearle ca.-1959- Sleeping Beauty concept painting for Disney

FURTHER READING

The Fantasy of the Middle Ages: An Epic Journey Through Imaginary Medieval Worlds

From the soaring castles of Sleeping Beauty to the bloody battles of Game of Thrones, from Middle-earth in The Lord of the Rings to mythical beasts in Dungeons & Dragons, and from Medieval Times to the Renaissance Faire, the Middle Ages have inspired artists, playwrights, filmmakers, gamers, and writers for centuries. Indeed, no other historical era has captured the imaginations of so many creators.

The Fantasy of the Middle Ages: An Epic Journey Through Imaginary Medieval Worlds (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2022) aims to uncover the many reasons why the Middle Ages have proven so applicable to a variety of modern moments from the eighteenth through the twenty-first century. These “medieval” worlds are often the perfect ground for exploring contemporary cultural concerns and anxieties, saying much more about the time and place in which they were created than they do about the actual conditions of the medieval period. With over 140 color illustrations, from sources ranging from thirteenth-century illuminated manuscripts to contemporary films and video games, and a preface by Game of Thrones costume designer Michele Clapton, The Fantasy of the Middle Ages will surprise and delight both enthusiasts and scholars.

interview with the authors at New Books Network

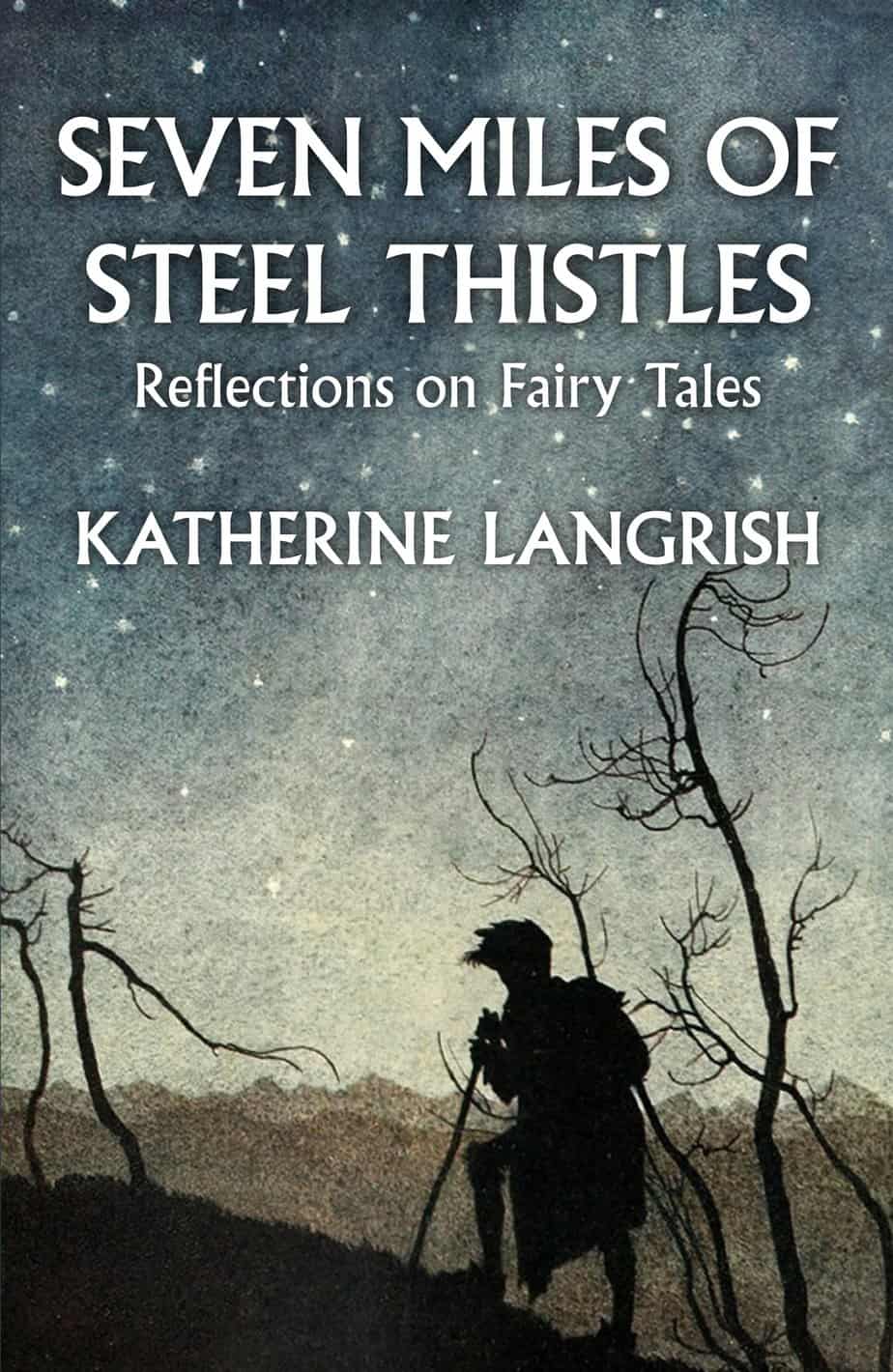

Katherine Langrish explores fairy tales, ballads and folk tales. She reflects on the role of women in fairy tales, discusses specific tales such as ‘Briar Rose’ and ‘The Juniper Tree’, and looks at wider themes of White Ladies, Water Spirits, Fairy Brides and many more.