Whether it’s women locked in attics, teenage girls protected by their fathers, children living in gated communities, missing girls or dead mothers, Rapunzel is a significant ur-story.

THE HISTORY OF RAPUNZEL

The life of a fictional woman hasn’t diversified much over the years. Rapunzel is not the only girl who was locked up — take the Irish myth of Ethlinn, for instance. Ethlinn was a moon goddess whose father imprisoned her in a tower so that she could not produce the son prophesied to kill him. Kind of like a cross between Oedipus and Rapunzel, don’t you think?

It seems so obvious it’s not even worth mentioning: The girl locked in a tower thing is a metaphor for how family members would gather around to protect a young woman’s virginity. The fertile woman’s body has historically (and into the present) never been considered her own.

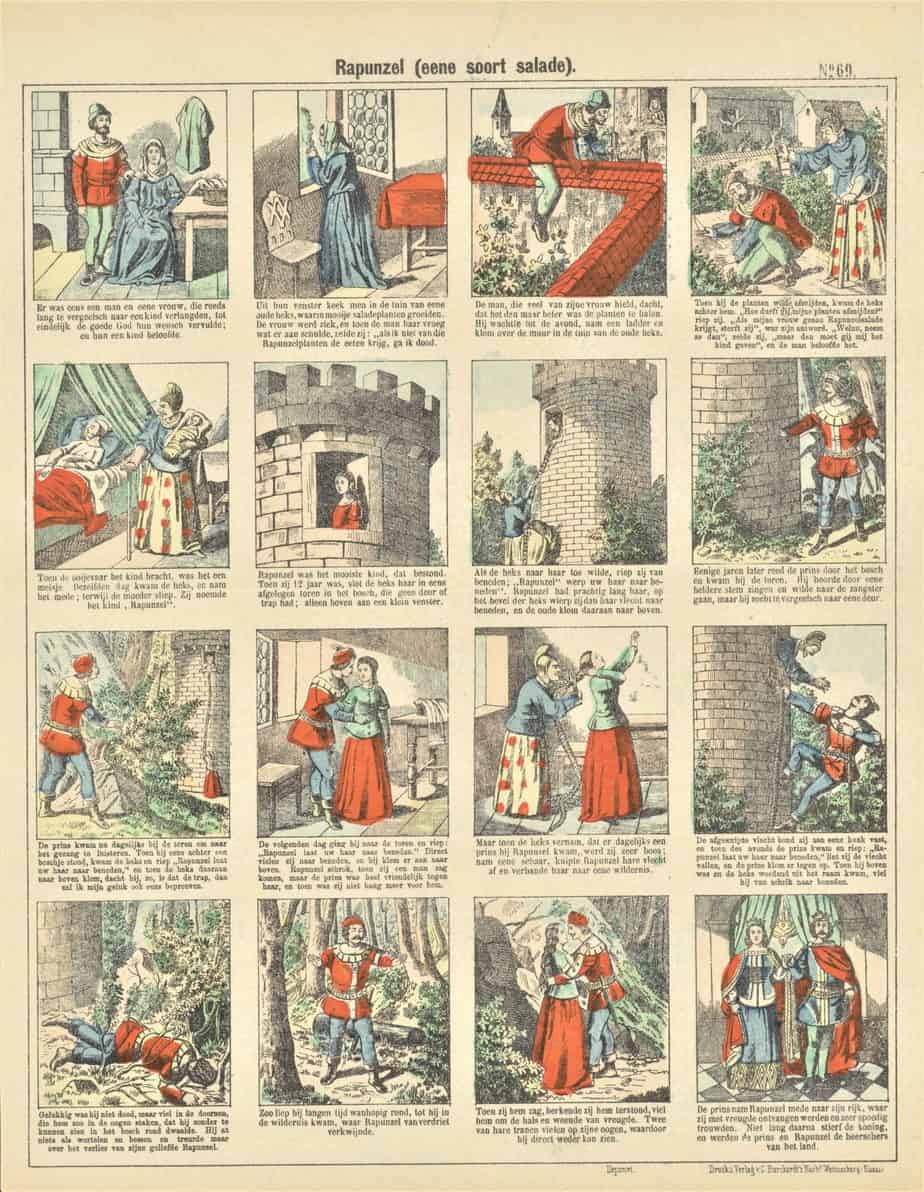

Patrisonella — ‘Neopolitan Rapunzel’ by Giambattista Basile (1630s)

This story predates the Grimm version by about 200 years. ‘Literary’ means it was written down rather than started orally. Neapolitan Giambattista Basile, like the German Grimm Brothers, was a collector of fairytales rather than a creator of them. He wrote down the story of Petrisonella. His sisters published a couple of volumes of his collections after he’d died.

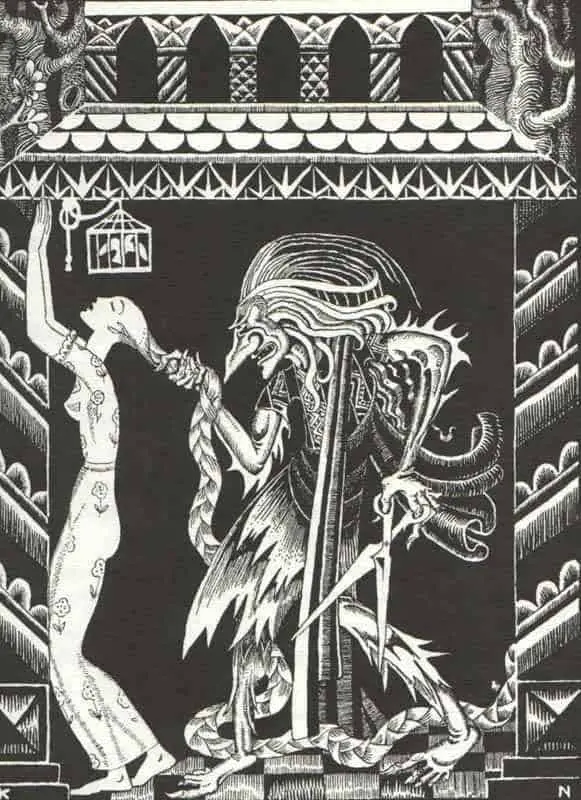

In this version our heroine is an active participant in the tale. She works out her own way to escape the tower. She is named after the vegetable which grows in the ogress’s garden.

Petrosinella isn’t given over at birth as Rapunzel is.

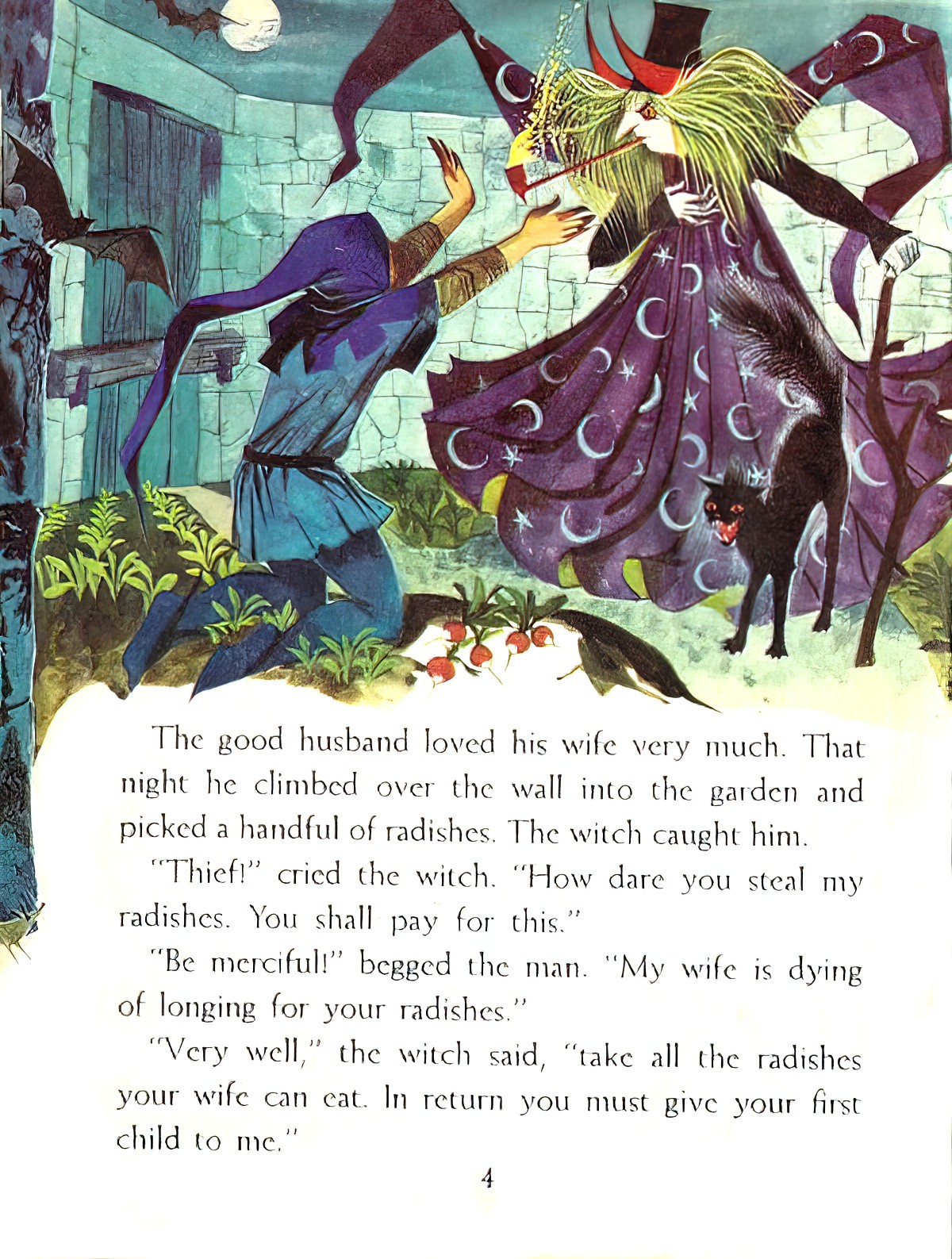

There’s still that backstory with the mother who has cravings for, steals the petrosine. (In Neapolitan, petrosine is parsley.) In this retelling it’s the wife herself who takes the parsley. The mother promises the ogress that she can have her unborn child. The ogress is going to kill her if she doesn’t comply. (Sounds fair. Parsley IS delicious.)

The child, Petrosinella (Little Parsley), lives with her parents but every day on her way to school she passes this ogress who whispers, “Tell your mother to remember her promise!”

The daughter doesn’t know the backstory of this, and repeats this to her mother day after day. The mother eventually advises her own daughter to say to the ogress, “Take it!”

Poor Petrosinella is taken. Dragged by the hair, in fact, and locked in a tower in the woods.

We might assume Petrosinella suffers from PTSD. If a human were to be locked up as Rapunzel was, she would not be thriving. We actually know this from real life examples, such as the case of Blanche Monnier. She knows what it’s like to have a family and friends. She’s basically been sacrificed by the mother who didn’t even tell her the truth. In this way, Petrosinella is an ancestor of ‘Ma’ in Emma Donaghue’s Room. It’s no surprise, really, that Donoghue is a writer who has a strong grasp on the history of fairytale and folklore. Apart from Room she has also written Kissing The Witch: Old Tales In New Skins. Another author with a strong background in fairytale and folklore is Australia’s Kate Forsyth, who brought Petrisonella — or rather the version as written by Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de La Force — back to life in her historical novel Bitter Greens.)

The ogress has no real motivation in this story because at this point in storytelling history it was assumed that certain women are inherently evil, ugly and dangerous.

I have no real issue with the enduring publication of fairytales, which come out year after year after year (presumably at the expense of original tales, because they sell), but I do wonder why publishers insist on continuing under the influence of Grimm rather than purposefully looking back further in time, when heroines were not such unilateral victims.

Persinette by Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de La Force (1698)

Charlotte-Rose also wrote a Girl In The Tower tale closely related to the Neapolitan Petrosinella. She wrote a bunch of things but is best remembered for “Persinette”.

In this version it’s Persinette’s father who takes the parsley. He doesn’t even have to take it. He makes a deal to exchange the baby for the parsley when the witch catches him in her garden. This makes no sense to a modern reader, but Jack Zipes explains that pregnancy cravings were taken very seriously in earlier times. It was thought that if pica cravings were not met, bad luck would befall the pregnancy, because cravings were given prognosticatory significance. “It was incumbent on the husband and other friends and relatives to use spells or charms or other means to fulfil the cravings.” (The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm edited by Jack Zipes). Other examples of stories in which pregnant women crave fruit and vegetables:

- Cherry Tree Carol (The Virgin Mary tells Joseph she’s pregnant by asking him to pick some cherries for her.)

- Duchess of Malfi by John Webster (apricots were believed to induce labour, a belief utilised here)

Anyone who has been pregnant lately will be keenly aware of all the rules around what you are and are not allowed to do if you’re pregnant. Fairytales remind us that even before cigarettes and the ready availability of soft cheeses, pregnant women were controlled via superstition taken seriously: It was thought that if a woman gave in to her cravings she would cause supernatural intervention which would bode poorly for the baby. This ties in with pre 20th century ideas that ‘control’ is what people valued in antiquity. Michel Foucault wrote about this, especially in regards to sex. (The idea that one’s sexual orientation defines you is modern. For ancient civilisations control over one’s own impulses is what defined you. Look to the Ancient Greeks.)

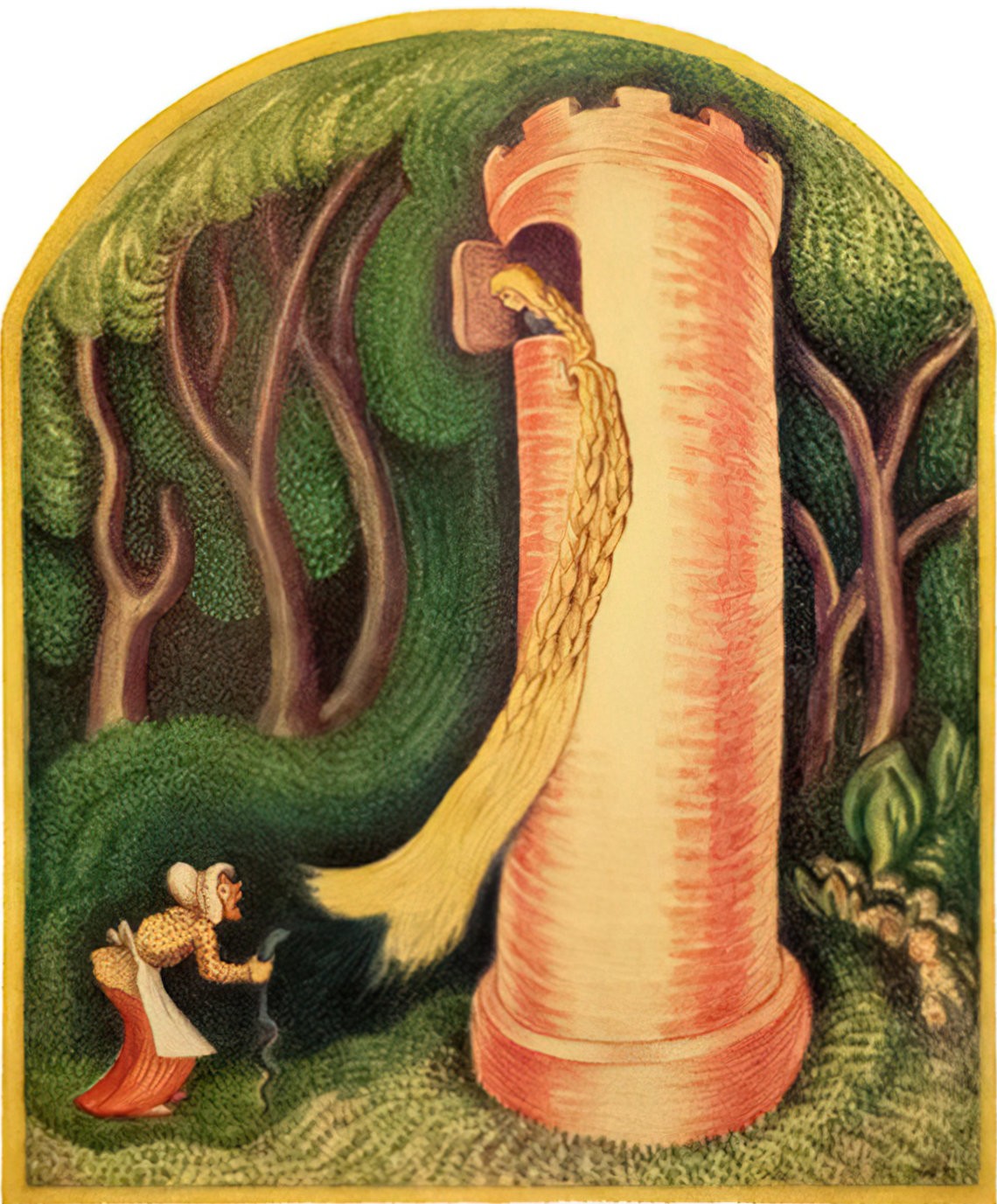

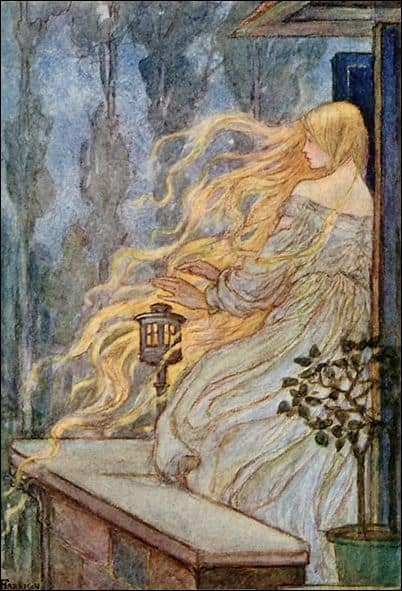

De la Force spends a lot of time describing all the luxuries that Persinette has in her tower. French culture at the time was all about having the best and newest luxuries. You’ll find similar descriptions of the Beast’s castle if you read the original French version of Beauty and the Beast. In both tales, the reader is encouraged to believe that the female prisoner is actually very lucky, having all these nice things around her. She’s, like, almost not even a prisoner at all!

In this version Persinette falls in love with the handsome prince in no time at all. Charlotte-Rose skirts around the wedlock issue by having them ‘married within the hour’. The speed at which Persinette goes from scared to fully in love is more than a little creepy by modern standards:

“He fell at her feet and kissed her knees with persuasive ardor. Persinette was frightened. She cried and then she trembled, nothing could calm her. Her heart was full of all possible love for the prince.”

In this version the fairy finds out Persinette has been ‘seeing’ the prince and is furious, but instead of banishing her to the forest she banishes her to a cute cottage by the sea which provides her magically with food.

For more on the author see here.

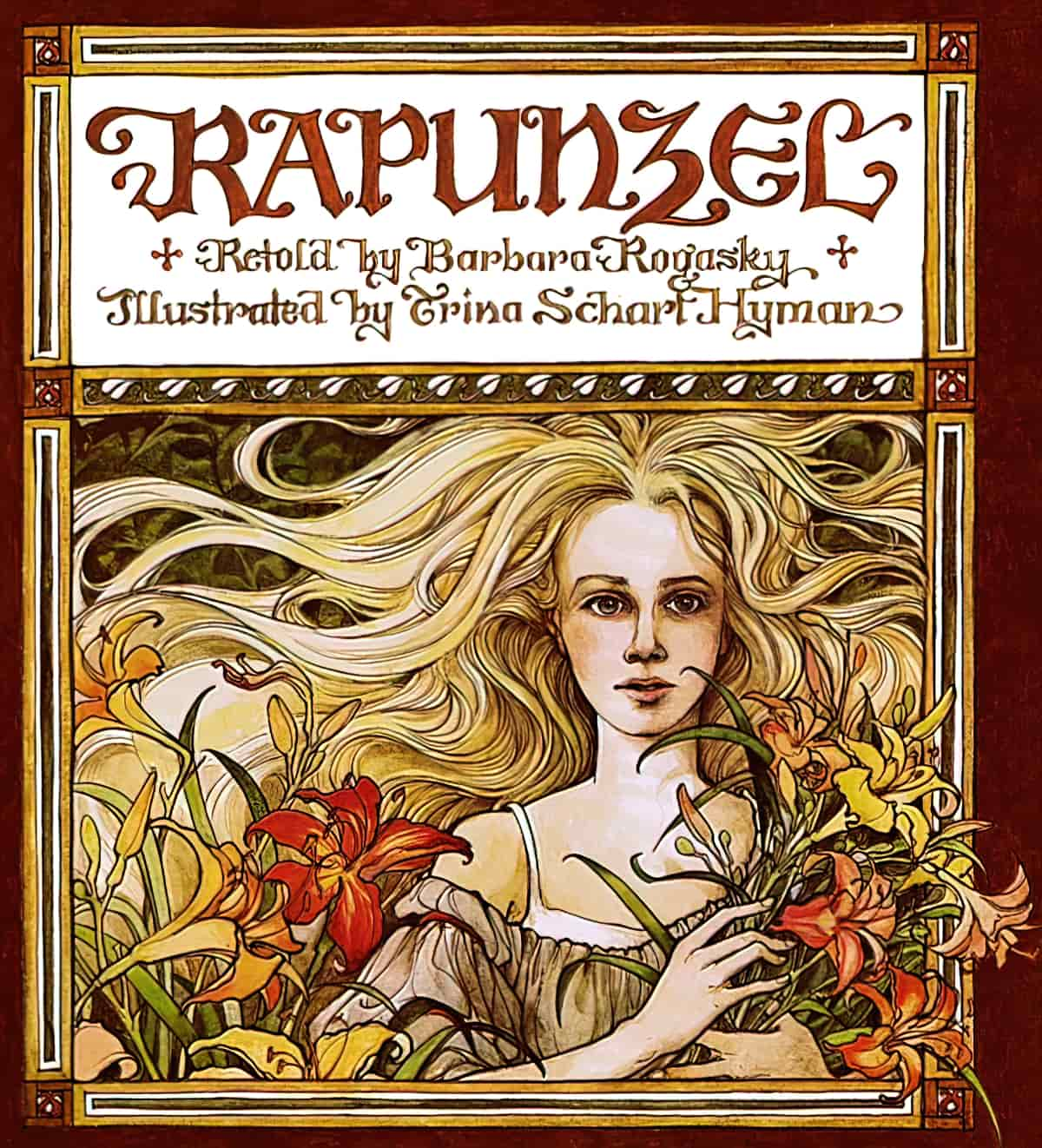

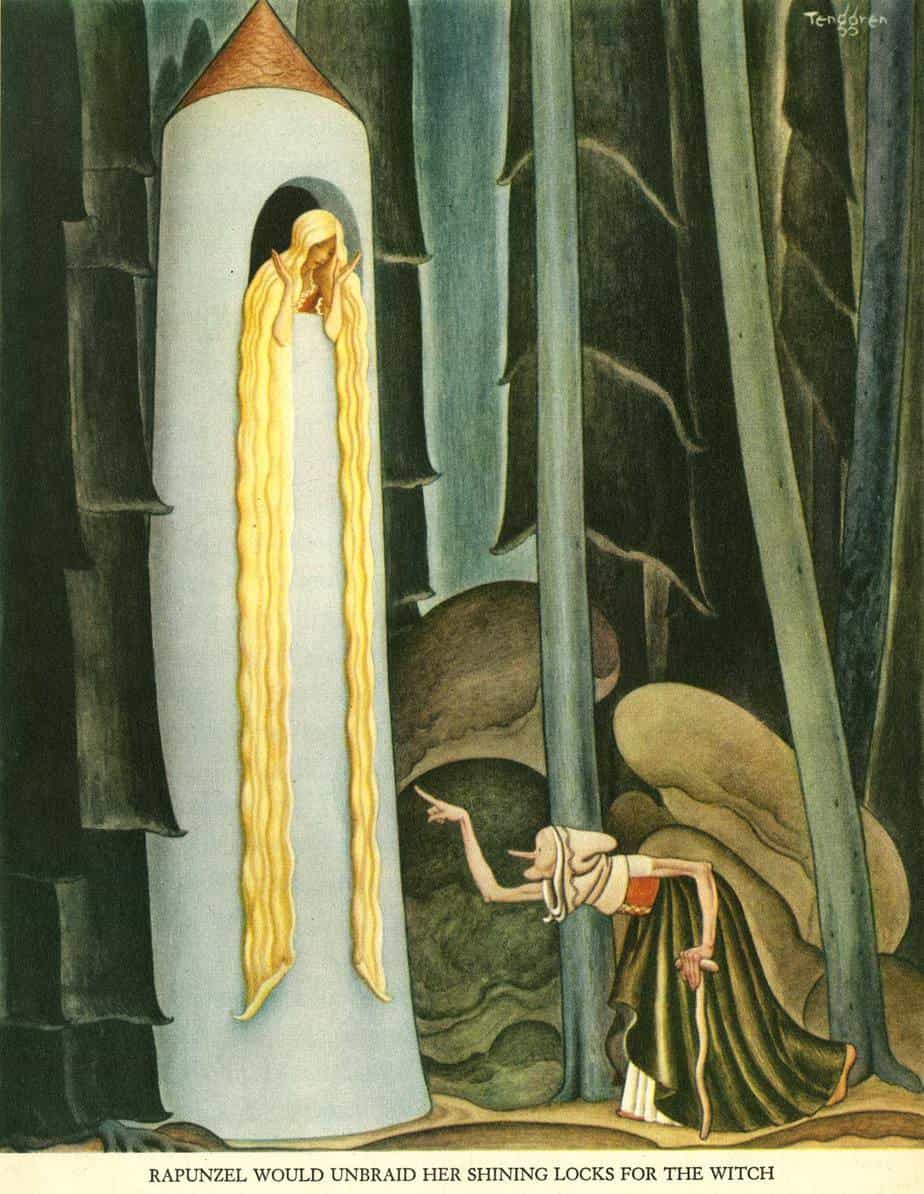

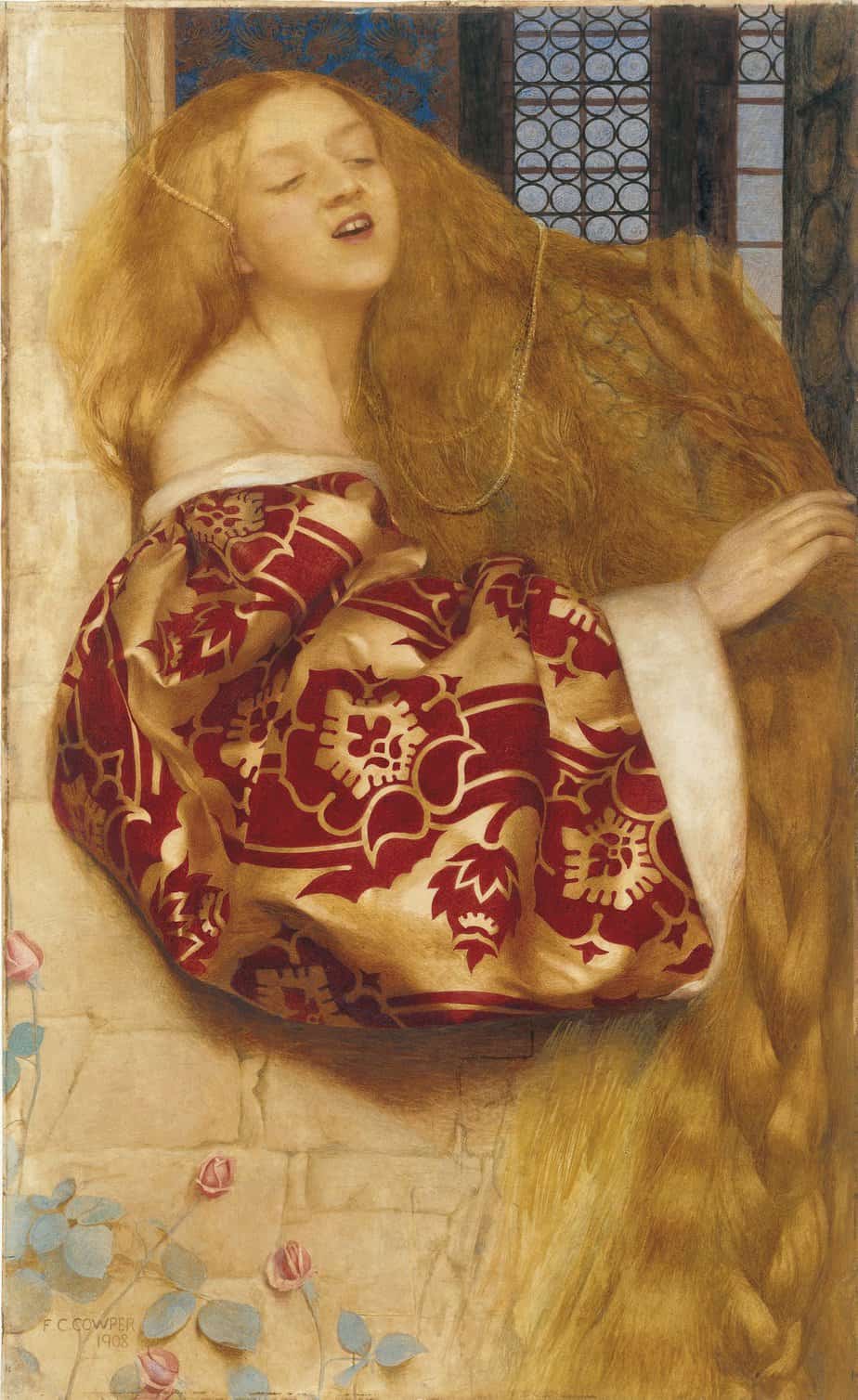

When Paul O. Zelinsky illustrated a modern retelling of Rapunzel he chose to paint in an art style reminiscent of this period.

What Did The Grimm Brothers Do To It? (1812)

As usual, the Grimm brothers modified it — or picked the best of many versions — to suit their own morals at the time. Specifically, they changed the ending, because remember they were trying to monetize their work by selling collections to kids instead of sitting at home while people sent them their stories. Oral fairy tales such as “Rapunzel” were never created specifically for a young audience:

The Grimm’s (sentimental) ending to the story of Rapunzel (where the Prince’s blinded eyes are magically restored after Rapunzel’s tears land on them) cannot be found in the oral tradition of this tale.

OUP

Here’s what else the Grimm brothers always did to classic oral tales: they took a brave, intelligent heroine and made her passive and naive.

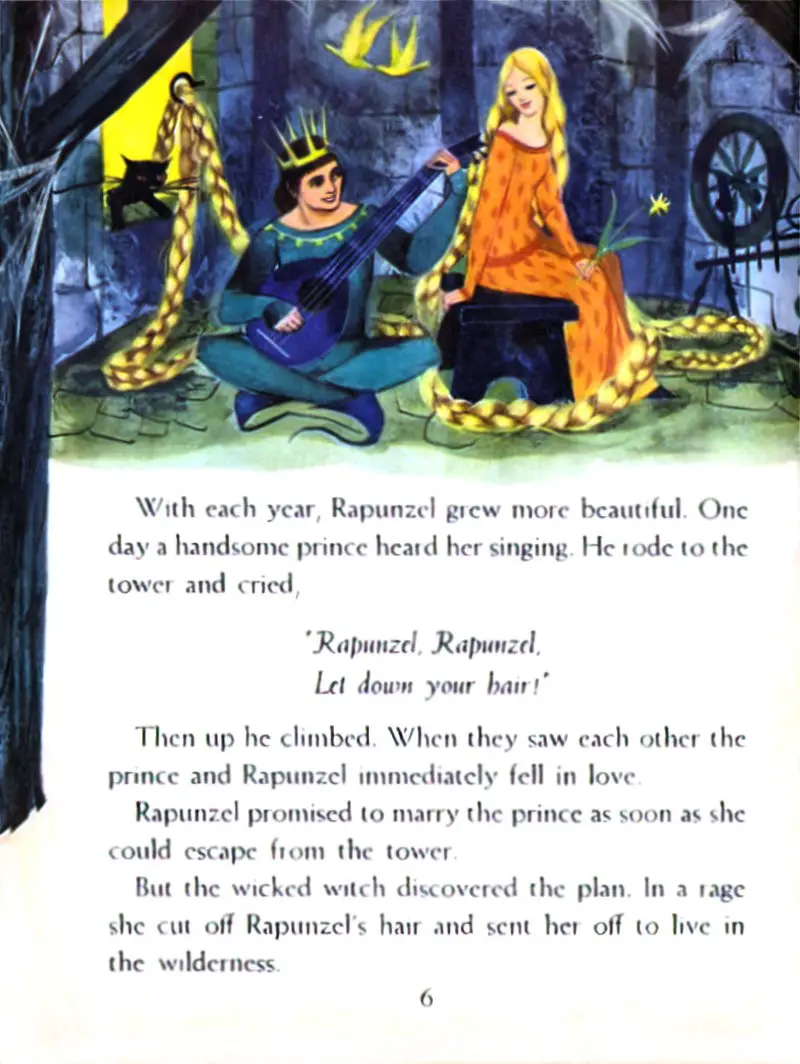

In order to avoid the controversial issue of Rapunzel getting pregnant before getting married, the Grimms have her instead ask the witch (as if she’s a true fool) why she’s so much heavier than the Prince. Some have argued that this Rapunzel is smarter than critics give credit for. For instance, it’s Rapunzel who comes up with the Prince’s plan when she says, “I will willingly go away with thee, but I do not know how to get down. Bring with thee a skein of silk every time that thou comest, and I will weave a ladder with it, and when that is ready I will descend, and thou wilt take me on thy horse.”

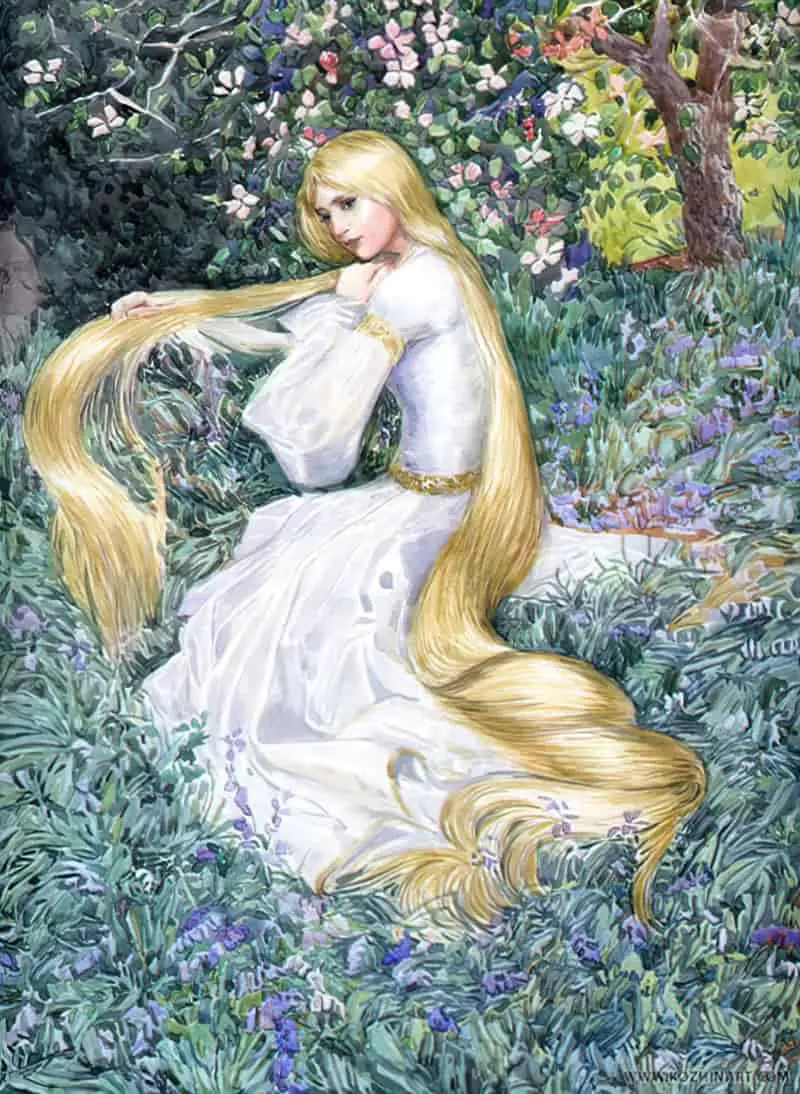

As you can see, our ‘ogress’ is now a ‘witch’ — basically another version of an inherently evil woman. The green vegetable stolen from the witch’s garden is now ‘rampion’ which actually refers to three different green, leafy vegetables. The rampion bellflower had leaves which were used like spinach and a root used like a parsnip. These days you don’t really hear about rampion outside this particular retelling of Rapunzel. (Unless you’re a keen gardener, I suppose.)

Barbie As Rapunzel (2002)

Similar to lots of feature-length films starring girls, appealing mainly to girls, the Barbie version of Rapunzel went straight to video. It was produced by Mainframe Entertainment and Mattel. A film like this is never going to get good critical reception and this is no exception.

Say what you will about the Barbie franchise — this version of Rapunzel is probably a bit better than the Grimm’s version. I mean, at least Barbie has agency. She ‘paints’ her way out of the tower. It passes the Bechdel test because Barbie is telling a story to her little sister, Kelly, who doesn’t have confidence in her own painting abilities.

I don’t want to oversell the feminist aspect. My argument is simply that this version looks no worse than the many, many book versions which are told to kids today.

What Did Disney Do To It? (2010)

I have a complicated relationship with Disney/Pixar. Like churches everywhere, they sit consistently slightly behind the times. Okay, Pixar are starting to do some genuinely good stuff. (Inside Out, Moana.) They get a lot of undue credit for sometimes ameliorating what are truly outdated values set in stone by the Brothers Grimm. For instance, when Disney made Rapunzel, they at least gave Mother Gothel a good reason to want a girl in a tower. In earlier versions of similar stories the ogress was given no motive. As 20th C feminist Marilyn French has written, it is important that female characters in stories are given motives for their evil doings:

Myths transforming or diminishing female figures like Hera elide such suggestions. Instead, they omit the past and transform the character of the female into something venomous, ugly, dark, mysteriously threatening. By erasing any reference to an earlier power or power struggle they make the hostility of these female figures appear unmotivated, a given. Social charter myths at least acknowledge intersexual conflict. Transforming myths do not acknowledge intersexual conflict. Transforming myths do not — thus the evil power of females appears to be biological, natural. Such a procedure penetrates the moral realm and affects an entire society’s view of women.

Marilyn French

The other thing Disney is credited for: keeping these tales alive. Without Disney/Pixar, I wonder how many parents would still be buying fairytale collections for their kids. Perhaps these fairytales would be getting lost to history right now, and reading them to our five-year-olds would seem as quaint and hipster as reading them The Jungle Book or tales from Norse mythology.

I’m surprised Disney didn’t get to Rapunzel earlier. Tangled was released in 2010, with a screenplay written by Dan Fogelman. He’s also known for Cars, Bolt, Fred Claus (for kids) and Crazy, Stupid Love (a rom-com about a middle-aged man who is forced to grow up after his wife says she wants a divorce).

In Fogelman’s own words, describing the story of Tangled:

It’s a really a two-hander of a movie. It’s really more than anything it’s about this love story at the center of the movie between the girl, Rapunzel, and the guy, Flynn.

Go Into The Story

Let’s take a look at the enduring appeal of Rapunzel.

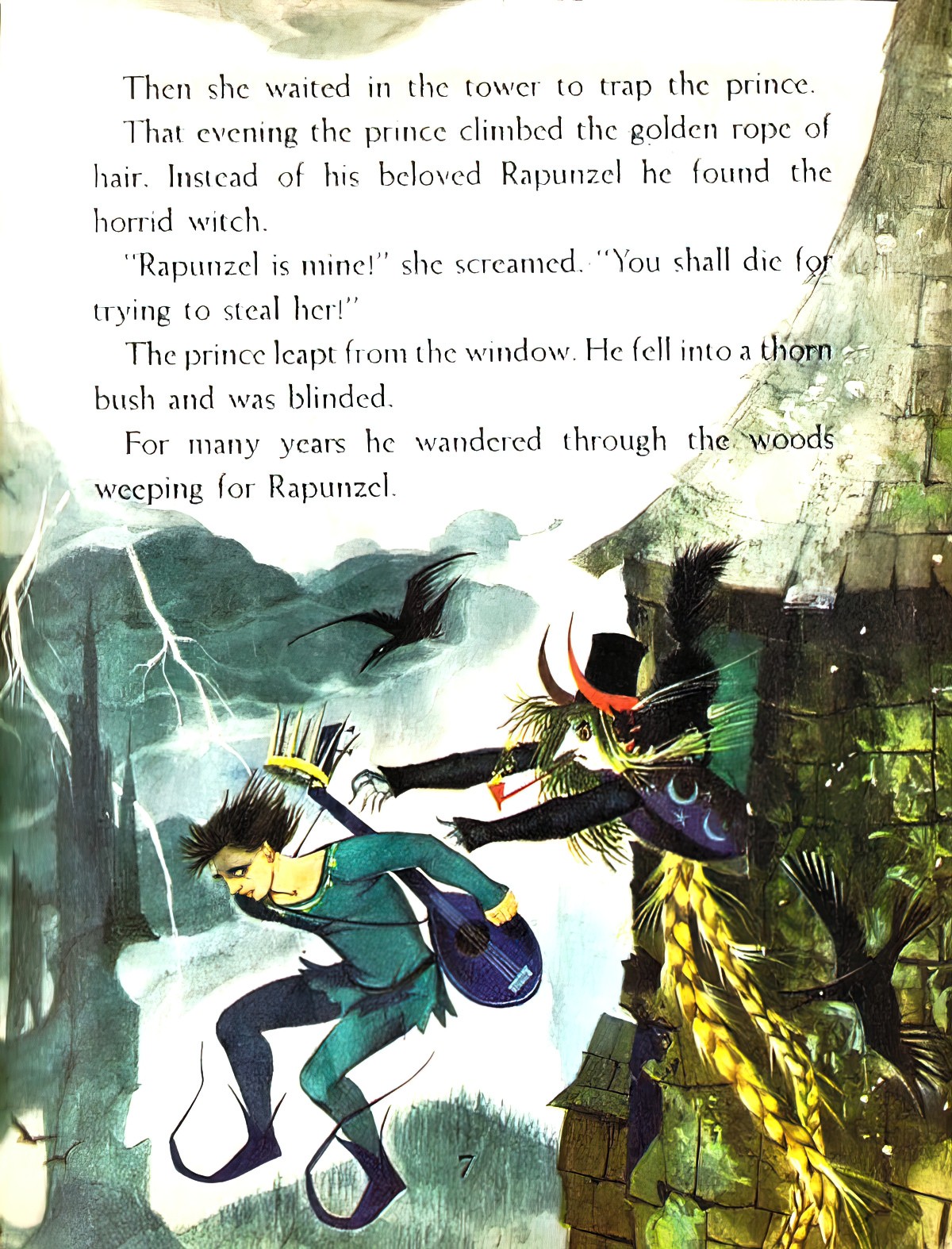

You probably think of a pretty girl up in a tower who lets down her long hair so her boyfriend can climb up to see her. True, it’s a little weird that she was imprisoned there by a witch, but still: kind of romantic. How’s this version: When the witch sees what Rapunzel and her boyfriend are up to in that tower room (hint: it’s not knitting), she cuts off Rapunzel’s hair and drops her into the wilderness to wander around alone. Then the witch sneaks up on the boyfriend, he jumps out of the tower window in fright, and blinds himself on thorn bushes. There is a lot of blinding in fairy tales.

Riveted

STORY STRUCTURE OF RAPUNZEL

There are so many versions of “Rapunzel” that I have to pick one to focus on for the story breakdown. I will take a look at the Grimm version, not because it’s my favourite at all, but because it’s the version I grew up with. I’m reading it from a sky-blue hardcover anthology published by Cathay Books in 1979.

In the Grimm version, the girl can no longer be the main character. It just doesn’t work because she is so passive. She might as well be a mannequin. So who is the main character? The main character is the one who changes the most. This does not refer to changes in circumstance (e.g. from rich to poor/alone to married). Who had some sort of awakening? The Grimms’ version posits the Prince as the main character. The prince is active.

The other difference in story structure when it comes to these really old tales: Modern readers don’t want to hear about the parents’ stories. A young adult novel these days isn’t going to regale the reader about how the heroine’s parents met. I guess family background was more important a few centuries ago, perhaps because it was thought that bloodlines were truly significant, and that if misfortune befell you, it must have had something to do with you deserving it, somehow, in a caste system of sorts.

How did the blind man get like that? Jesus’ disciples ask. Was it he who sinned, or his parents? My New Age mind/body connection was just another way to force the lepers outside the town walls. Vulnerability cannot enter here. Mortality cannot enter here. It was another way to push my fears away from myself and onto someone else. If you are ill, you can fix it yourself. If you cannot fix it, then you are to blame. It was, I realize looking back, pseudo-spiritual eugenics.

Superbabies Don’t Cry

Today it’s enough to write a tragic tale about anyone from any background because according to modern morality, bad things happen to anyone at all. (There is still the rose-tinted idea that anyone can pull themselves out of hard times just so long as they work hard, but that’s an evolution for a future Golden Age of Children’s Literature, perhaps helped along by the Trump administration.)

SHORTCOMING

The prince, like any young adult, is considered incomplete until he has found himself a wife. I guess he can’t become King until he finds a beautiful wife. So that’s his main problem.

DESIRE

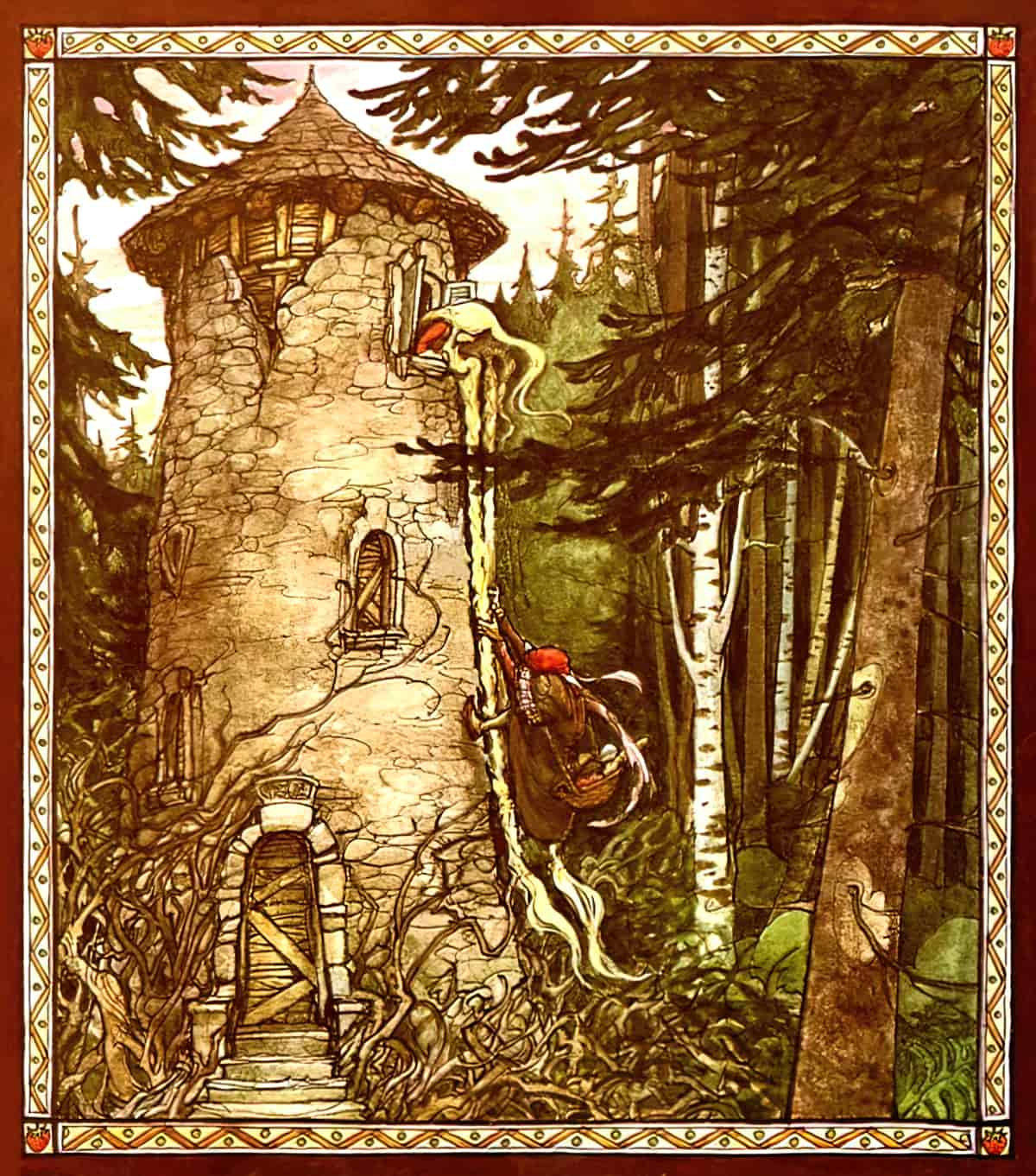

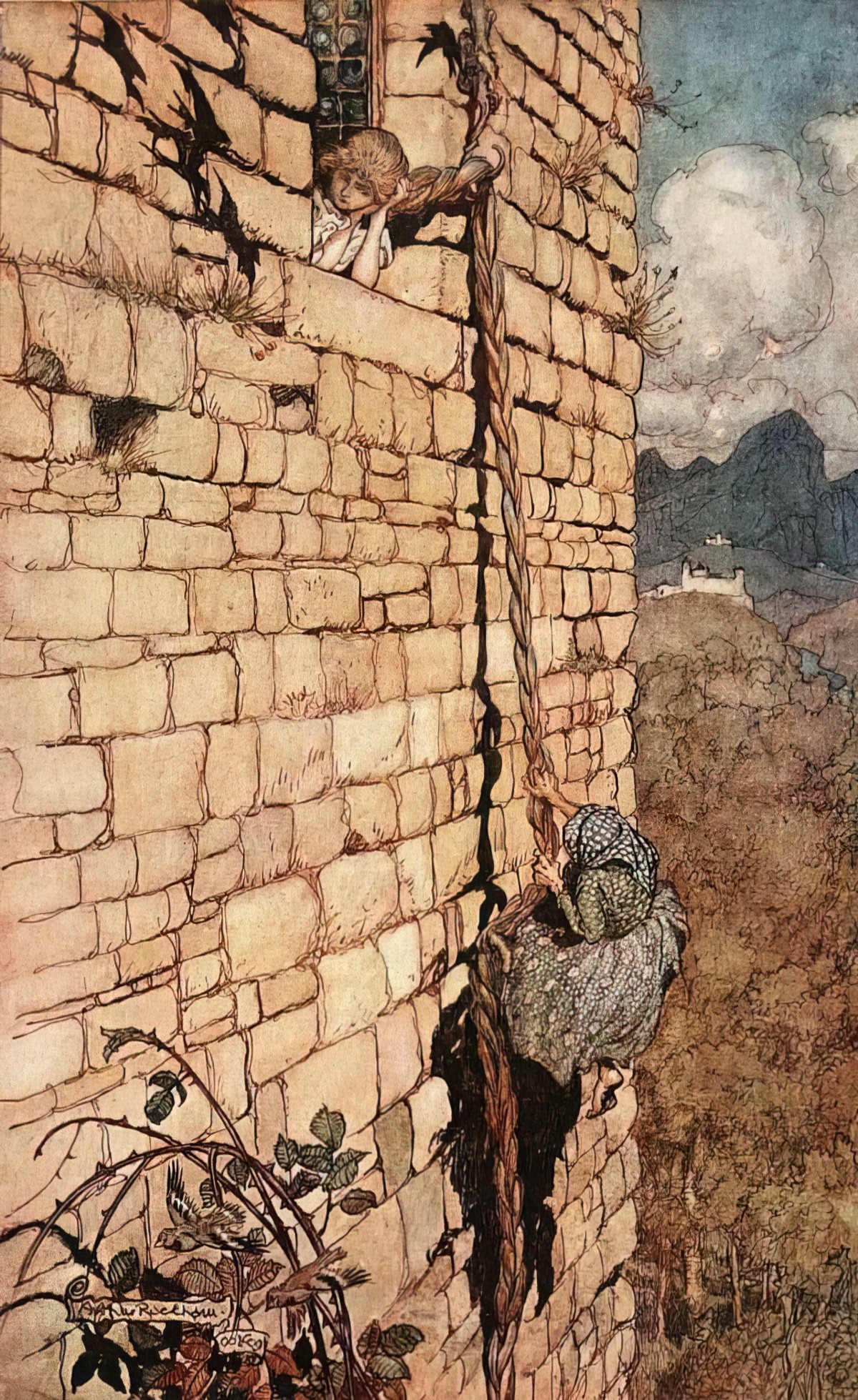

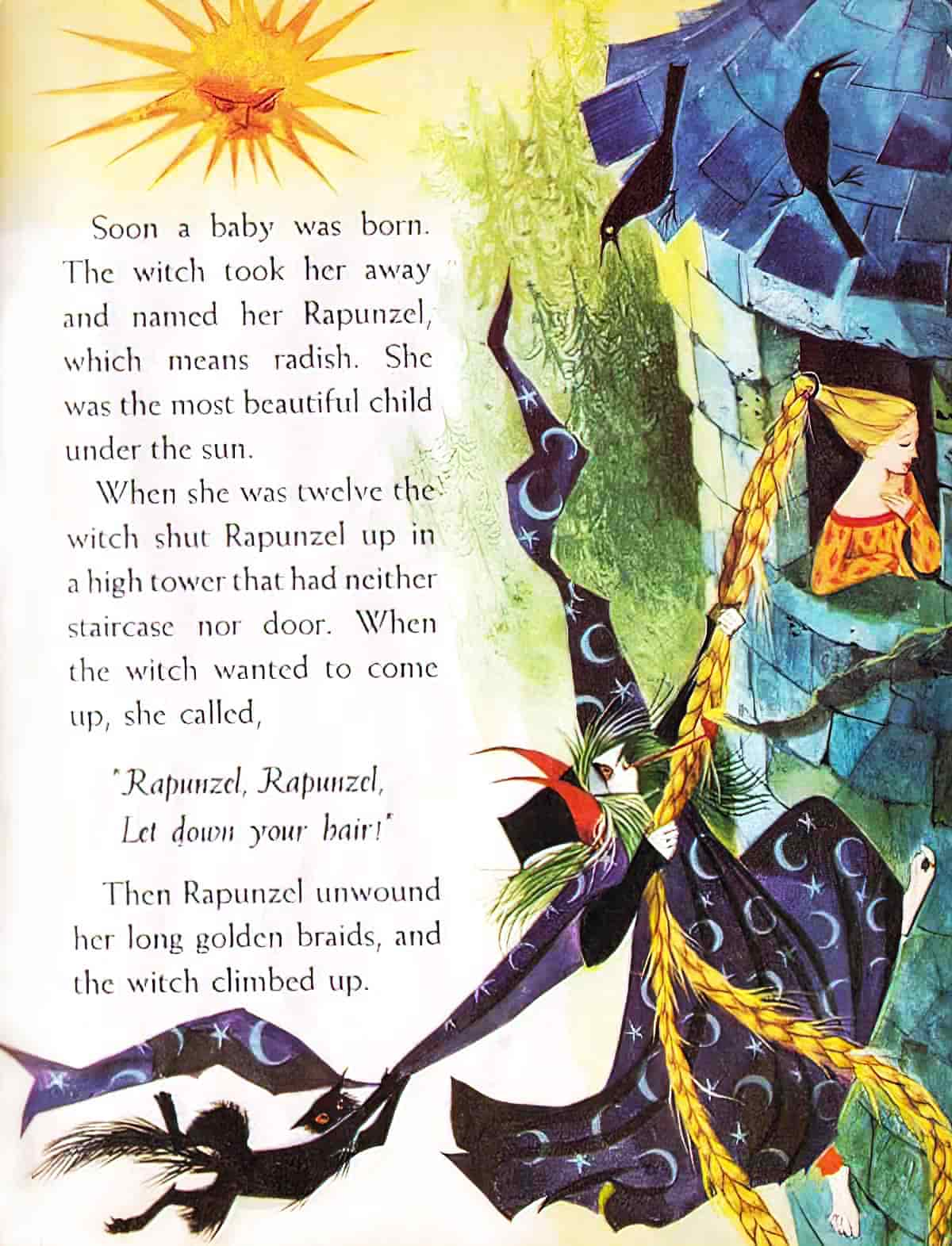

He wants that young woman with the beautiful singing voice. Unfortunately there is no door into the tower. He can’t get in.

OPPONENT

The witch has locked his prize in a tower to keep her away from the likes of him.

PLAN

He waits and watches. The witch climbs up the girl’s hair, using it as a rope. He’ll do the same. (Because the girl is pretty stupid she doesn’t notice that a young man sounds different from an old woman, I guess.)

BIG STRUGGLE

That bit where the prince flings himself in despair from the ledge after seeing the old woman instead of Rapunzel. Part of me wonders if he assumes Rapunzel has transmogrified into that old woman. If he lives in fairy tale land he might well have thought so. Anyhow, if he can’t have Rapunzel he’d rather be dead. Unfortunately, he suffers a fate worse than death. He is blinded on some sort of thorny bush. If he were dead, at least he’d be in Heaven. At least, that’s how readers saw things a few hundred years ago. For the same reason a tale like Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl is not actually a tragedy — it has a happy ending because the little girl gets to see her dead grandmother in Heaven. Nope, going blind here on Earth is worse than being dead in Heaven.

ANAGNORISIS

He roams about in utter misery. He can do nothing but lament. He does this for ‘some years’. At last he finds himself in the wilderness. Now I’d like to draw your attention to The Symbolism Of The Forest. The Forest is where you will go to find yourself in the very pit of despair. We can assume he had some sort of epiphany. Oh, hang on, nope, he would have continued to be miserable but he stumbled upon Rapunzel who had also found herself in that very same forest.

NEW SITUATION

Rapunzel has been caring for a couple of twins all this time. We assume they’re his. Yes, let’s do that. He takes Rapunzel and his twins back to his own kingdom where they are joyfully received. They live long in happiness and contentment together. And by the way, he’s not blind anymore — not in the Grimm version, because Rapunzel has magical eye-healing tears.

SEE ALSO

Singing The Bones Rapunzel episode (podcast)

Kate Forsyth is a Rapunzel expert and has written both fiction and non-fiction based on Rapunzel stories. Check out her blog.

A unique collection presenting Kate Forsyth’s extensive academic research into the ‘Rapunzel’ fairy tale, alongside several other pieces related to fairy tales and folklore.

This book is not your usual reference work, but a complex and engaging exploration of the subject matter, written with Forsyth’s distinctive flair.

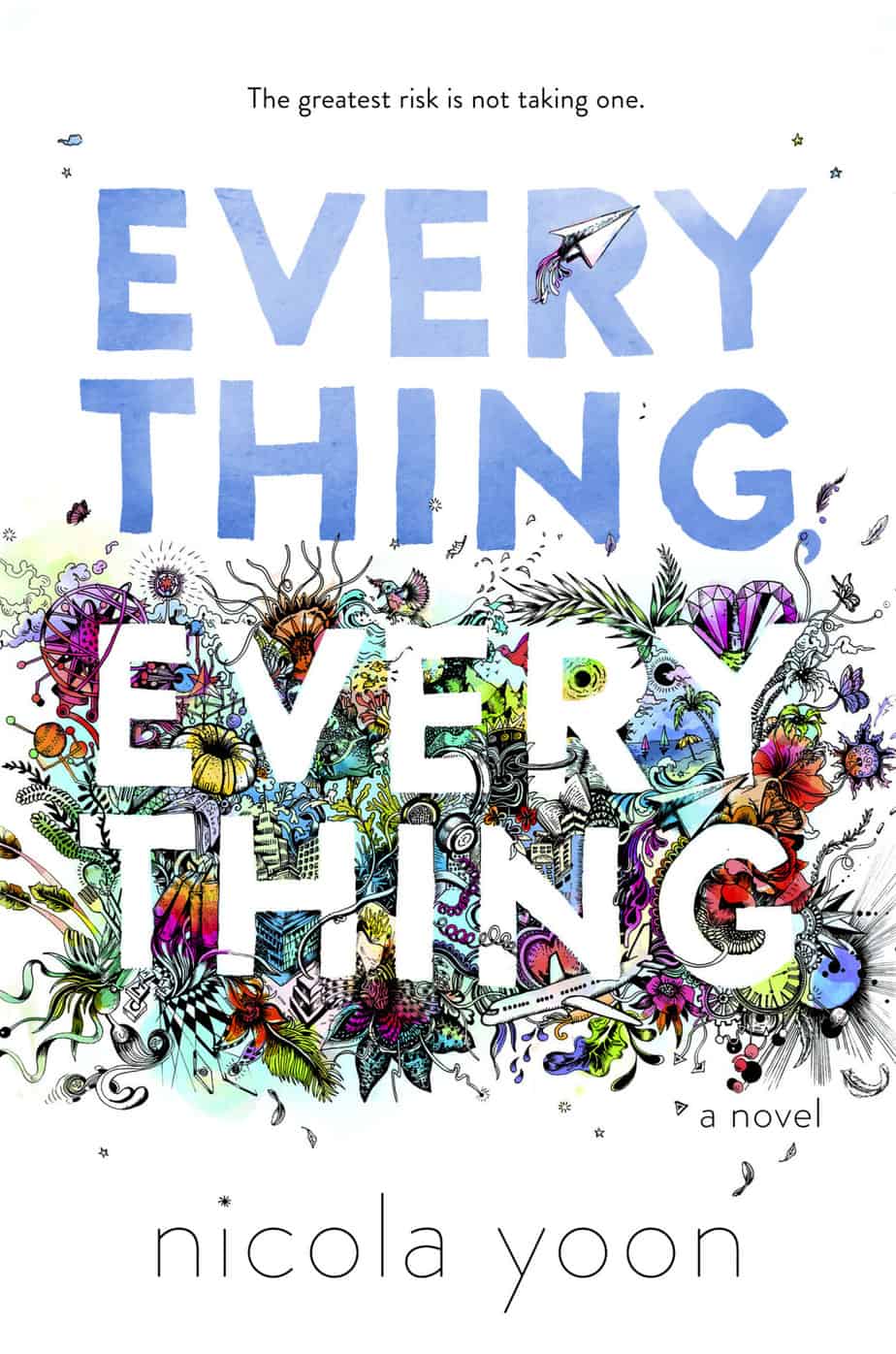

My disease is as rare as it is famous. It’s a form of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency, but basically, I’m allergic to the world. I don’t leave my house, have not left my house in fifteen years. The only people I ever see are my mom and my nurse, Carla.

But then one day, a moving truck arrives. New next door neighbors. I look out the window, and I see him. He’s tall, lean and wearing all black—black t-shirt, black jeans, black sneakers and a black knit cap that covers his hair completely. He catches me looking and stares at me. I stare right back. His name is Olly. I want to learn everything about him, and I do. I learn that he is funny and fierce. I learn that his eyes are Atlantic Ocean-blue and that his vice is stealing silverware. I learn that when I talk to him, my whole world opens up, and I feel myself starting to change—starting to want things. To want out of my bubble. To want everything, everything the world has to offer.

Maybe we can’t predict the future, but we can predict some things. For example, I am certainly going to fall in love with Olly. It’s almost certainly going to be a disaster.