“People In Hell Just Want A Drink Of Water”: When it comes to neighbours who’ve been through terrible hardship, no one asks all that much of you. You’re not going to fix their problems, but you can extend just a little kindness and that’ll go a long way.

“People In Hell Just Want A Drink Of Water” is another story about a community rather than an individual. These stories tend to say something about how communities work, treating these groups of people as a flawed individual. I see what people mean when they call Annie Proulx ‘deterministic’. If an individual hero has some choice in how they act, a community is not a sentient being — once a certain social group has been formed, things must take their course. I am feeling that way lately about the state of politics. We’re entering a new age of right-wing horribleness, and there doesn’t seem much we can do about it until ‘things have taken their course’. The best I’m hoping for in 2017 is that this far right thinking will swing back hard the other way, afterwards. After what? I don’t know.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

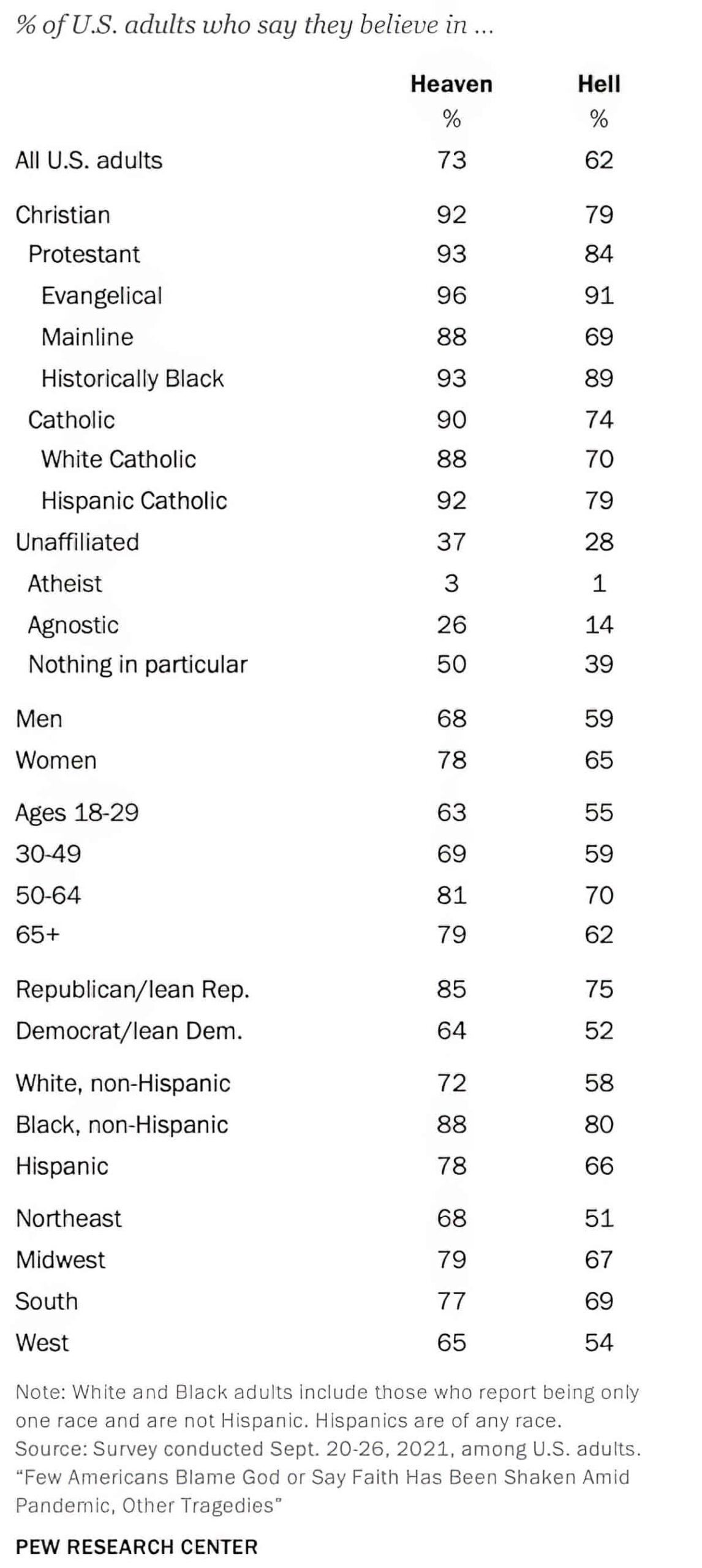

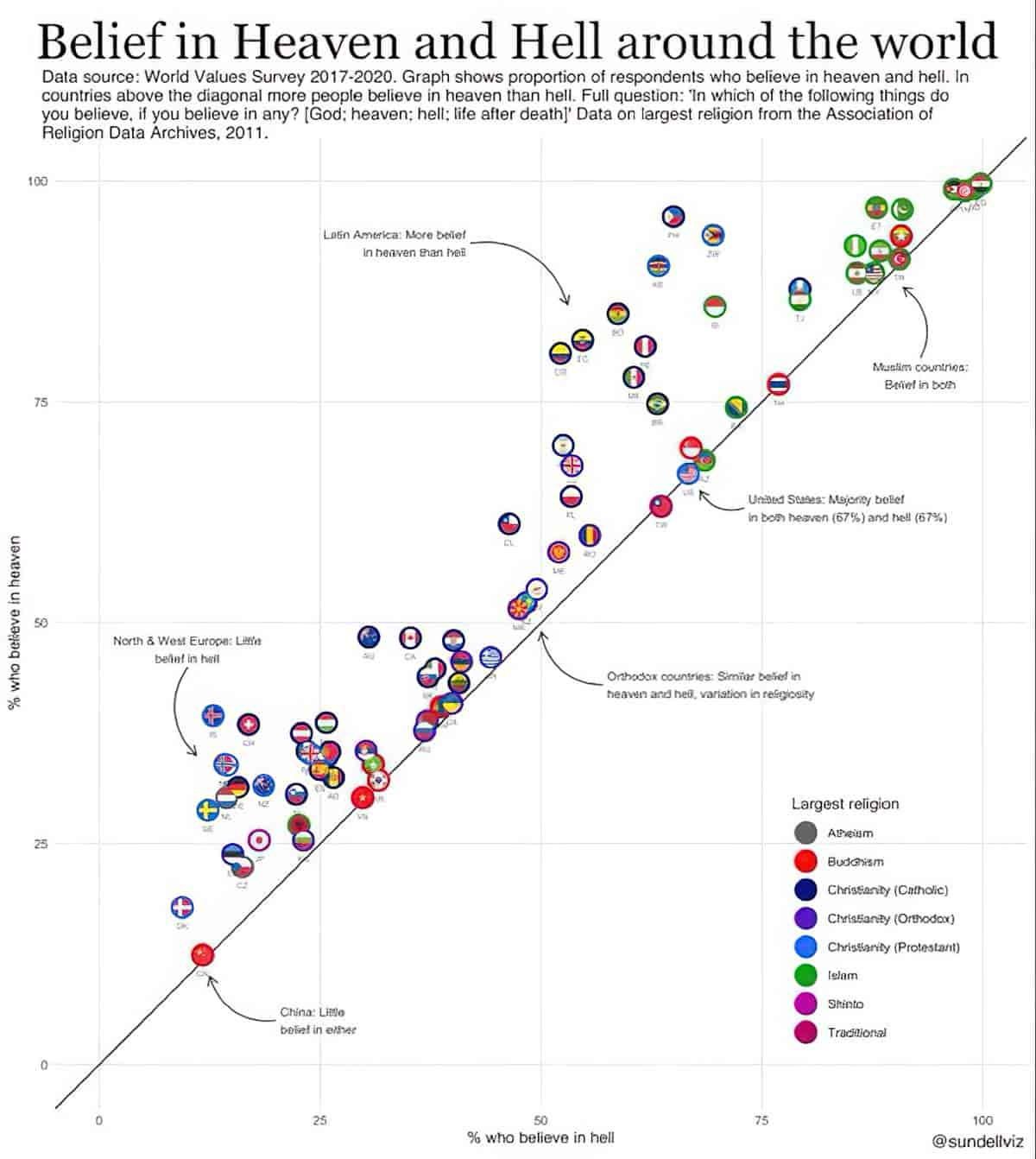

You don’t have to be religious to believe in Satan, because the devil is all around us. Literally. He’s in our canyons, mountains, harbors, waterfalls, orchards, and streets. He is the very landscape of America.

See for yourself on The United States Devil Map, a creation by Jonathan Hull

SETTING OF “PEOPLE IN HELL JUST WANT A DRINK OF WATER”

“Frankly, almost every single one of the stories that I write about in Wyoming are founded in historical fact,” Proulx insists in an interview (Wyoming Library Roundup 7). According to the author, this is true even about the horrific “People in Hell Just Want a Drink of Water” which ends with the discovery of a character monstrously maimed in an auto wreck who has been castrated by his neighbors with a dirty knife, and has consequently turned black with gangrene: “And that really happened. It happened here in the late 1800s,” Proulx upholds (Wyoming Library Roundup 7). Indeed, in the “Acknowledgements” section of her first volume of Wyoming stories, Close Range, Annie Proulx traces the genesis of “People in Hell Just Want a Drink of Water” to “a few disturbing paragraphs” found in a regional Wyoming history by Helena Thomas Rubottom, Red Walls and Homesteads, and which was “the take-off point for the story”

Bénédicte Meillon

The term ‘geographical determinism’ is the full phrase used to describe the work of Annie Proulx. Alex Hunt explains what that means in The Geographical Imagination Of Annie Proulx: Rethinking Regionalism. It occurs when a text retains elements of local colour fiction but the characters are limited by the surrounding geography and climate. It’s sometimes known as ‘environmental determinism.’

Determinism was popular with geographers in the early decades of the 20th century (when this story is set) but fell out of favour because it became linked to justifications for imperialism and racism. Jared Diamond, who in 1997 wrote Guns, Germs, and Steel did a lot to restart the conversation about determinism and basically made it okay to talk about that again. Annie Proulx was of course writing these Wyoming stories at this exact time. There must have been some sort of zeitgeist. Now it is okay to look again at the ways in which a physical environment (climate, natural resources, disease, plagues) shape individuals and cultures.

You stand there, braced. Cloud shadows race over the buff rock stacks as a projected film, casting a queasy, mottled ground rash. The air hisses and it is no local breeze but the great harsh sweep of wind from the turning of the earth. The wild country – indigo jags of mountain, grassy plain everlasting, tumbled stones like fallen cities, the flaring roll of sky – provokes a spiritual shudder. It is like a deep note that cannot be heard but is felt, it is like a claw in the gut.

Proulx’s Wyoming stories are best read with a mind to intertextuality — we must take into account America’s long history of Westerns. She ‘turns the iconic into the ironic’. For example:

- cowboys >> try-hard cowboy rodeo kids (“The Mud Below“)

- epic hero >> tragic hero who does not quite make it home (“The Half-Skinned Steer“)

- cowboys on Western ranches >> Yankee farmers on New England farms (in Proulx’s New England stories)

- and in this story, brass-balled cowboys on Western ranches >> a literally castrated, brain-damaged tragedy

STORY STRUCTURE OF “PEOPLE IN HELL JUST WANT A DRINK OF WATER”

Point of View in “People In Hell Just Want A Drink Of Water”

How do you write a story about a community without zooming in on one individual? It’s partly to do with pulling right out to wide-angles with your narrative point-of-view.

Proulx’s conventional narrative point of view, a detached omniscience, keeps us mostly suspended above characters, outside them, as though stationary in the weather and wind, at one with panoramic landscape as characters are not. The effect of long- or medium-range camera shots sustains the inequality of satiric comedy, the engraved lines of caricature. The detached perspective lends itself to panoramic evocations of landscape, a fondness for pan shots, rather than sustained closeups of people or forays into interior consciousness. That perspective restlessly hovers above like Wyoming’s eternal wind, scouring and stripping down faces, personalities, trucks, trailers, barns. Often we know the varied faces of topography, the fickle forces of weather, better than characters who remain — with such notable exceptions as “Brokeback Mountain’s” Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist — at arm’s length.

The Geographical Imagination Of Annie Proulx: Rethinking Regionalism

SHORTCOMING

Mostly, Proulx peoples her landscape with losers: characters lacking sufficient imagination or will or money or luck to create alternative lives in their chosen place and, thereby, gain complexity, some roundedness. Here, these losers look like winners in their natural environment. But are they really?

The story follows the (mis)fortunes of two big ranching families who neighbour each other, starting much further back than the final events, with entire histories of the boys’ fathers, in particular, and some of the mothers’ misery.

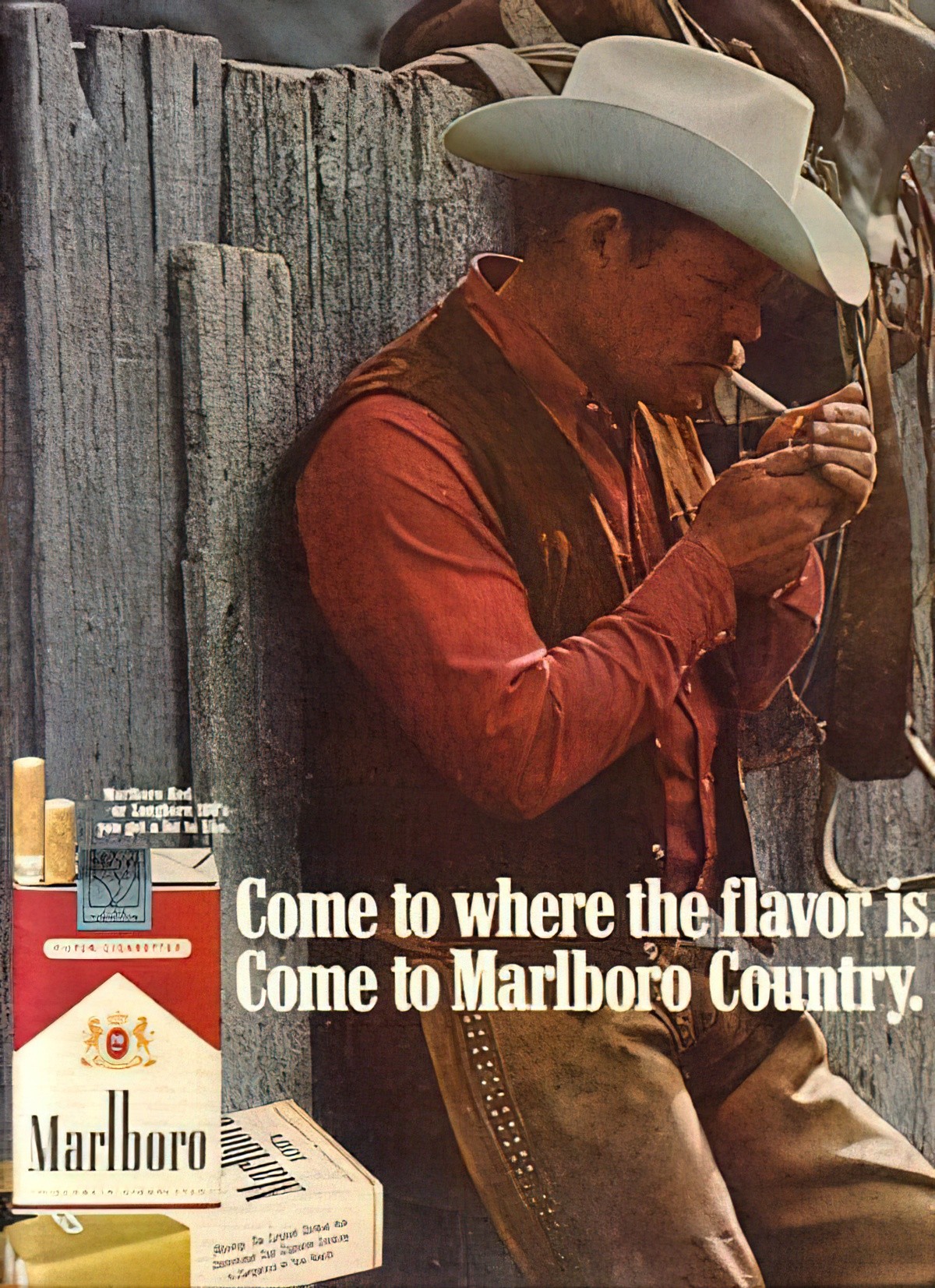

The Dunmires: They work livestock. The patriarch is called Ice. He has eight sons. The mother couldn’t cope and ran off. They ‘seem to have stepped from a Marlboro cigarette ad’. (Alex Hunt.) Proulx’s description of their hardiness is almost superhero level stuff — sleeping out alone on the plain when young buttons, in the rain, with nothing but a tarp for protection. Even when badly injured they’re shown to power through the pain. Like a John Wayne character they are honorable and chivalric.

The chivalry and sheer doggedness of these men is exactly what’s needed for that harsh life out on the plains, but their lack of feeling and compassion leads to a darker turn later in the story, with Ras Tinsley their victim.

The Tinsleys: Ras Tinsley returns home to the ranch after a disfiguring car accident in New York. His face is heavily scarred. Annie Proulx has a lot of scarred characters, but more widely in literature a scarred character tends to be either a victim or a monstrous villain. These are the only two narratives we really have for disfigured people. The Dunmires, too, have only those two narratives within the story itself, and go with the second one.

DESIRE

Because of their morality and chivalry the Dunmire boys see it their job to protect the whole community from sex offenders.

Ras Tinsley wants only to go out and ride his horse about. No one really knows what’s going on inside his head, or how brain damaged he is.

OPPONENT

Ras Tinsley stands in the way of The Dunmires wanting a community free of disfigurement — his very existence goes up against everything they stand for: strength and usefulness in work.

PLAN

The Tinsley parents are approached by one of the Tinsley brothers about Ras possibly exposing himself but the father’s having none of it. Getting no joy from the father, someone goes ahead and castrates the young man.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle scene takes place off the page. The revelation that Ras has been castrated and is now dying from the infection is horrific enough.

ANAGNORISIS/NEW SITUATION

Annie Proulx spends the final paragraph of the story spelling out the reason for the telling of it:

That was all sixty years ago and more. Those hard days are finished. The Dunmires are gone from the country, their big ranch broken in those dry years. The Tinsleys are buried somewhere or other, and cattle range now where the Moon and Stars grew. We are in a new millennium and such desperate things no longer happen.

If you believe that you’ll believe anything.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH “PEOPLE IN HELL JUST WANT A DRINK OF WATER”

The Homesman, a film by and starring Tommy Lee Jones, has some equally harrowing scenes which, to the modern audience, look like mental illness — perinatal depression, probably.

East Of Eden is another story with two families — the Trasks and the Hamiltons — living side by side, having different luck.