Mavis Gallant died last year, but if she were still around she might not think much of my attempt to dissect her stories in order to learn from them:

Gallant is dismissive of analysing or explaining her work, and distrustful of academic attempts to do so.

The Guardian, 2009

The same Guardian article says of her work, ‘One of the most striking things about Gallant’s work…is its cinematic quality, shifting perspectives and chronology, resulting in what Lahiri calls “narrative that refuses to sit still”.’ This is the sort of story that, if you were to upload it to a peer review writing site, would be shot down as an example of ‘head-hopping’. Yet as Gallant’s work demonstrates with ease, it’s possible for an adept omniscient narrator to dive in and out of heads without confusing the reader in the slightest.

Mavis Gallant is a master at condense writing. Of novels she said:

A lot of it is just stuffing between the important things. In between is nothing.

Mavis Gallant herself feels that she didn’t develop her own style until the 1960s, yet this one was written a decade before then.

PLOT OF MADELINE’S BIRTHDAY

Mrs Tracy adored the Connecticut house where she had spent all her summers. Her Husband, Edward, came out weekends. This summer she had two guests. One was Madeline, 17, daughter of an old friend. She was the child of divorced parents and an unhappy girl. Paul, the other guest, was a German boy, a little older, extremely shy and serious. Mr. Tracy felt that the gloomy atmosphere they caused was bad for their daughter, Allie, aged 6. It was Madeline’s birthday but she was in her usual bad temper. Mrs. Tracy tried to smooth things out as best she could so the day would be happy.

Full story available at The New Yorker online (behind a paywall).

SETTING OF MADELINE’S BIRTHDAY

This story was published in 1951 and the setting is modern for the time. Apart from workings of the telephone (which back then needed operators) and absence of the Internet (in which Paul could have emailed his professor), there is not much about the story that is different from a modern-day setting. We are told that this is set in rural Connecticut.

We are told that this takes place seven days before Labor Day, significant because both of the young house guests are counting down the days until the end of summer, when they can leave. In the popular imagination, summer is, in contrast, a happy and carefree time, not a time to be endured.

THEME OF MADELINE’S BIRTHDAY

It is about characters juxtaposed but estranged, about children living without parents, about women living without husbands. It is about attitudes toward foreigners (Mrs. Tracy is disappointed in Paul, who is dark, bespectacled, and “anything but arrogant,” for not corresponding to her notion of Germans), and about the repercussions of history on personal lives. It is essentially about a denial of truth; for Mrs Tracy, who believes fervently in the healing powers of summers spent in her country house, who identifies wholly with its breezes and hinges and coverlets, has only the dimmest perception of the people surrounding her. Nonetheless, Mrs. Tracy makes a single observation that redeems her. “They’re both adrift, in a way,” she says of Madeline and Paul. Here Mrs. Tracy names a condition that is central to Gallant’s writing. Her characters (including, as we shall see, Mrs. Tracy herself) are all adrift, either cut loose from their origins or caught between currents that are personal, temporal, political, sometimes a combination of all three. Bringing that drift into focus is the essence of Gallant’s art.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s introduction to a selection of Gallant’s stories published by The New York Review of Books.

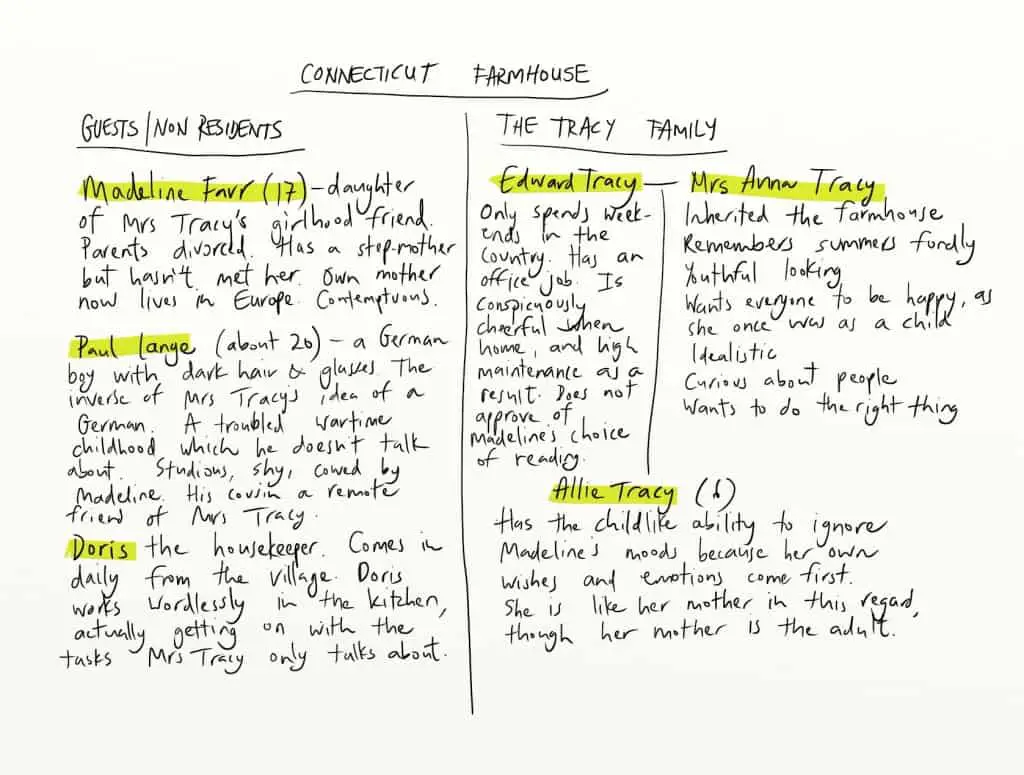

CHARACTERS OF MADELINE’S BIRTHDAY

Mavis Gallant introduces a complex cast of characters in the economy of a short story.

The theme of this short story is conveyed through the attitude of Mrs Tracy. Point of view is important, switching between close third-person POV and a more omniscient one when Gallant chooses to tell rather than show. The story starts with the point of view of Mrs Tracy, switching next to that of Madeline, then to Mr Tracy. POV is not strictly adhered to, switching only after double paragraph breaks; the narrator weaves in and out of heads as appropriate.

I know who they are, what they do and what they are saying to each other. And I know more than they do, because I know about all of them.

Mavis Gallant

The main juxtaposition is that between Mrs Tracy’s memories of childhood at the farmhouse, and the reality of living with a single daughter and an emotionally distant husband who is there only on weekends. In an attempt to recreate the bustling, lively childhood she remembers, Mrs Tracy invites guests each summer. There is no backstory about Mrs Tracy’s childhood; it is enough for the reader to be told that it was marvellous: ‘Technically, the Connecticut house belonged to his wife, who had inherited it. Loving it and remembering her own childhood there, she looked upon her summers as a kind of therapy to be shared with the world.’

This main juxtaposition is foreshadowed/explained with a series of present-day incongruities. First there are the incongruities that Mrs Tracy notices herself:

1. Madeline is not the bright-humored girl she thought she might be. Instead, she is a teenage girl suffering the aftermath of a broken family, a father who has left to remarry and a mother who can’t cope with the fact and who has gone off to Europe.

2. Paul is the inverse of Mrs Tracy’s idea of a German. He is dark not blonde, can’t swim, doesn’t enjoy the outdoors.

3. Madeline and Paul do not get on even though they are fairly close in age. So the young house guests themselves serve as contrasts, with Paul being of stable mood and Madeline being emotional; Paul being tidy, Madeline being messy; Paul being sensitive to the emotions of others, Madeline deliberately brushing over them. ‘They did not even have a cake of soap in common.’

Then there are the incongruities that Mrs Tracy is not aware of, but which the reader is privy to via the nature of the storytelling:

1. Although Mrs Tracy is full of plans, she’s not a woman of action, instead leaving the task of making Madeline’s birthday cake up to the housekeeper. Mrs Tracy can’t even remember telling the housekeeper about the birthday cake, thinking she might actually be making waffles for breakfast. While Mrs Tracy is ‘propelled’ out of the house, Doris has ‘a deliberate tread’. Mrs Tracy has an active imagination, who (ironically and comically) imagines that Doris’s imagination may have been ‘uncommonly fired’. Even the task of braiding her own daughter’s hair is off-loaded to the seventeen-year-old houseguest. Mrs Tracy is not the practical sort. ‘[Madeline] could hear Mrs Tracy downstairs, asking Doris if she had ever seen such a perfect morning. Doris’s answer was lost in the whir of the electric mixer.’ In an attempt to make her own life exotic, she thinks of Madeline as a ‘jeune fille’ (when she could just as easily have thought ‘young girl’).

2. Mrs Tracy’s routine life at the farmhouse is not the lively setting she strives to achieve, and so the contrast between the house of her imagination and the reality of running a household is stark. Unlikely comparisons come from Mrs Tracy, demonstrating her richer inner world: ‘The hall seemed weighted at one end—like a rowboat, she thought.’ She finds her husband’s morning greetings tiresome precisely because nothing new happens overnight, and because he says the same thing each morning he’s there.

After lunch with a lawyer friend on a trip to Montreal in 1955, he drove her back and stopped in front of “a very charming looking house with vines growing up it. ‘I’d love a house like that,’ he said. And I said, ‘It’s not for me.’ Saying, ‘How was your school day?’ every evening . . . I’d run away.

Mavis Gallant

Mrs Tracy says to her daughter, “My summers have always been so perfect, ever since I was a child.” But the reader knows this isn’t true, from the single paragraph outlining the various houseguests over the years, from Mr Tracy’s point of view, in which it is revealed that one of the previous summer guests had been a single mother who killed herself.

2. Although Mrs Tracy is curious about Paul’s troubled childhood in wartime Germany, hoping to use him for her own entertainment, he doesn’t talk about the war at all. Mrs Tracy’s curiosity shows a lack of empathy for a boy who is probably suffering post-traumatic trauma to some degree. Mrs Tracy’s need for socialising and merriment at her idyllic house in the country doesn’t equate to empathy for others. She wonders why the boy sleeps with his shades drawn, perhaps because she’d like to spy on him herself, but likely simply a metaphor for Paul’s introverted ways.

3. Although Madeline is younger in age, it is Madeline who is world-weary and Mrs Tracy who has maintained a youthful but unsustainable optimism. This is established in the first paragraph: The morning of Madeline Farr’s seventeenth birthday, Mrs. Tracy awoke remembering that she had forgotten to order a cake. It was doubtful if this would matter to Madeline, who would probably make a point of not caring. The difference in attitude is underscored later on in the story, when Mrs Tracy enters Madeline’s room to wish her a happy birthday, and Mrs Tracy ‘looks younger’ than the birthday girl. While Madeline was ‘ideally happy’ during her three weeks of isolation in her mother’s abandoned apartment, Mrs Tracy is at her happiest when surrounded by people.

4. Then there is the literary symbolism. For example the radio announcer says that ‘McIntoshes were lively yesterday…but Roman Beauties were quiet‘. Even the garden life is in contrast. The Roman Beauty, incidentally, is a compact evergreen shrub with aromatic, needle-like, dark green leaves with contrasting silver undersides. Paul looks out Madeline’s window and observes that “The pear tree is dying.” Madeline has already failed to attract the positive attention of Mr Tracy, she doesn’t acknowledge the masculinity of Paul and is feeling down that she has no romantic possibilities in her life.

The shape of the pear is suggestive of feminine form. As such, it has wide influence as a symbol of feminine sexuality and fertility. A healthy and flowering pear tree is a symbol of a strong capacity for reproduction. As a result, it also represents motherhood. A pear tree laden with fruit is a promise that birth, growth and longevity will be bestowed upon a newborn child.

So there we have garden-inspired contrast again, between Madeline’s nubile age and the dying of the pear tree.

LANGUAGE TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

Mavis Gallant uses dialogue tags skilfully. Rather than using, say, adverbs, she explains the subtext of dialogue in a single phrase:

“You probably haven’t read it,” Madeline said, intending the insult.

The ‘starched coverlet’ of Mr Tracy’s bed is a transferred epithet. We learn as the story goes on that the word ‘starched’ could in fact be applied to Mr Tracy himself.

The description of Madeline’s dream is described as an accurate portrayal of how dreams can intersect with the real environs:

In the next room, Madeline had stopped crying and fell asleep. She dreamed that someone had given her a dollhouse. When a bell rang downstairs, it merged into her dream as something to do with school. Actually, the ringing was caused by the long-distance operator, who had at first reported that the circuits to New York were busy and was now ready to complete the call.

The reason for the dream itself is significant, not necessarily in any Freudian way, but because the difference between dreamscapes and reality have been the central theme of the story. Note that Madeline is woken from her dream by a call about a call regarding Paul’s essay; real life minutiae of the dullest kind.

HOW IT ENDS

Sometimes characters in a short story have some sort of epiphany. Other times, it is remarkable that they haven’t changed at all. Who has changed in this story? Mr Tracy realises that he is silly to let the teenaged guest dictate the emotional well-being of his household. “She’s only a kid,” he says, and agrees to come home for Madeline’s birthday dinner. His wife, on the other hand, refuses to believe that things are not hunky dory. “People often say things,” she explains to her young daughter, “You must never pay attention to what people say if you know the opposite to be true.”

By this point, the reader of the story knows that the opposite is true; that no one in this household is particularly happy, and that Mrs Tracy refuses to admit it. The birthday party will go on, presumably, as Mrs Tracy wishes it to, with everyone else there under sufferance. Specifically, the story ends with Mrs Tracy telling Allie for the umpteenth time to call Madeline and Paul so that ‘we can get breakfast over with and get this day under way’. By this point, even Mrs Tracy is starting to endure things. Earlier, Madeline overheard her remarking to Doris what a beautiful day it is. So the last sentence serves to highlight to the reader the contrast between hopes/perceptions and realities.

QUESTIONS LEFT OPEN FOR THE READER

I’m not sure if I’m meant to be wondering this, but I found myself wondering about the nature of the relationship between Madeline and Mr Tracy. Why does Madeline get so upset at a small slight from Mr Tracy in the library? If she cares about his opinion of her, perhaps she has conflicted emotions. Has something happened while Mrs Tracy was absorbed in her own fantasy world? Or is Madeline simply missing her own father, hoping for a more present and engaging father figure for the summer? It is likely that Mr Tracy has no attraction to the girl. His thoughts of her hair are simply about its being ‘too long and thick for the season’. I suspect his assessment of the girl’s hair would be one of admiration if this were a Lolita sort of story.

OTHER SPECS

Approximately 3400 words broken into 1000, 900, 1200, 300 word segments.

The entire story takes place over the course of a few hours, maybe less than an hour, before breakfast.

This story is the first in a collection of Gallant’s earliest stories.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH

Katherine Mansfield’s “The Garden Party“, in which a teenage girl starts her day in high spirits but ends in a quite different frame of mind. See also Katherine Mansfield’s “Bliss” for an example of a pear tree used symbolically.

Mavis Gallant herself recommended anyone who aspires to be a short story writer should read Chekhov.

She has only two words of advice for aspiring short story writers: read Chekhov! “Anybody who has the English language and doesn’t read the wonderful translations of Chekhov is an idiot.” She also admires Eudora Welty, Marguerite Yourcenar and Elizabeth Bowen, although she was disappointed to read Bowen’s letters to her lover Charles Ritchie, whom Gallant knew. “She turns out to be a snob.

WRITE YOUR OWN

- A birthday (or other instance of contrived fun) which doesn’t go to plan

- A summer (or other season) spent in a place where you didn’t want to be

- A character who perseveres with a positive attitude despite surrounding circumstances which fail to live up to expectations