Jack and the Beanstalk is also known as Jack The Giant Killer, which kind of ruins the ending, so no wonder they changed it.

WHERE TO HEAR “JACK AND THE BEANSTALK” READ ALOUD

If you’d like to hear “Jack and the Beanstalk” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Jack and the Beanstalk” was published in two parts in Feb 2021.

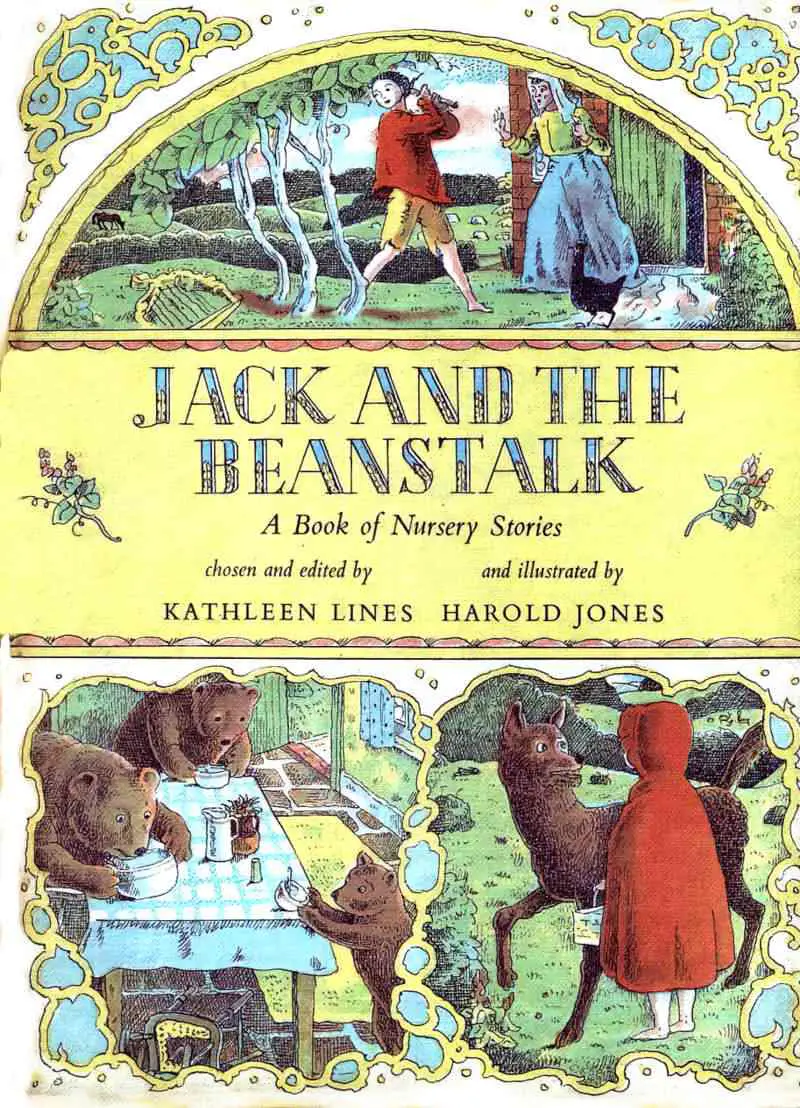

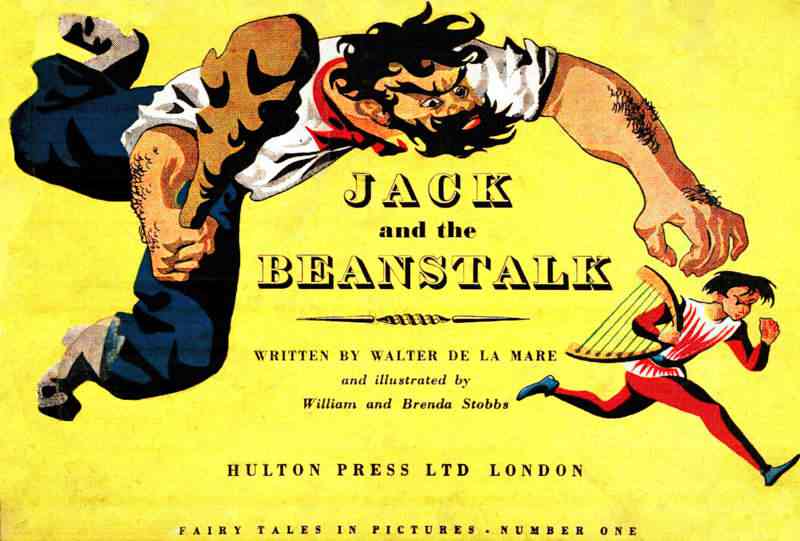

The story has been around for ages and ages as part of English folklore. An ancestor of Jack and the Beanstalk appeared in a printed pamphlet in 1734, and it’s clearly not intended for a child audience.

The first known print version to look like the story we know today was published by a London bookseller called Benjamin Tabart. This was in 1807.

There are hundreds of versions of this story, so I’ll stick to the Grimms’ version.

STORY STRUCTURE OF JACK AND THE BEANSTALK

Jack is poor, goes up a beanstalk, finds giant and goose that lays golden eggs, heads back with goose, defeats giant, no longer poor.

If in doubt about story structure, it is always useful to refer to fairy tales for validation — they contain the DNA of almost every story we tell. Take Jack and the Beanstalk:

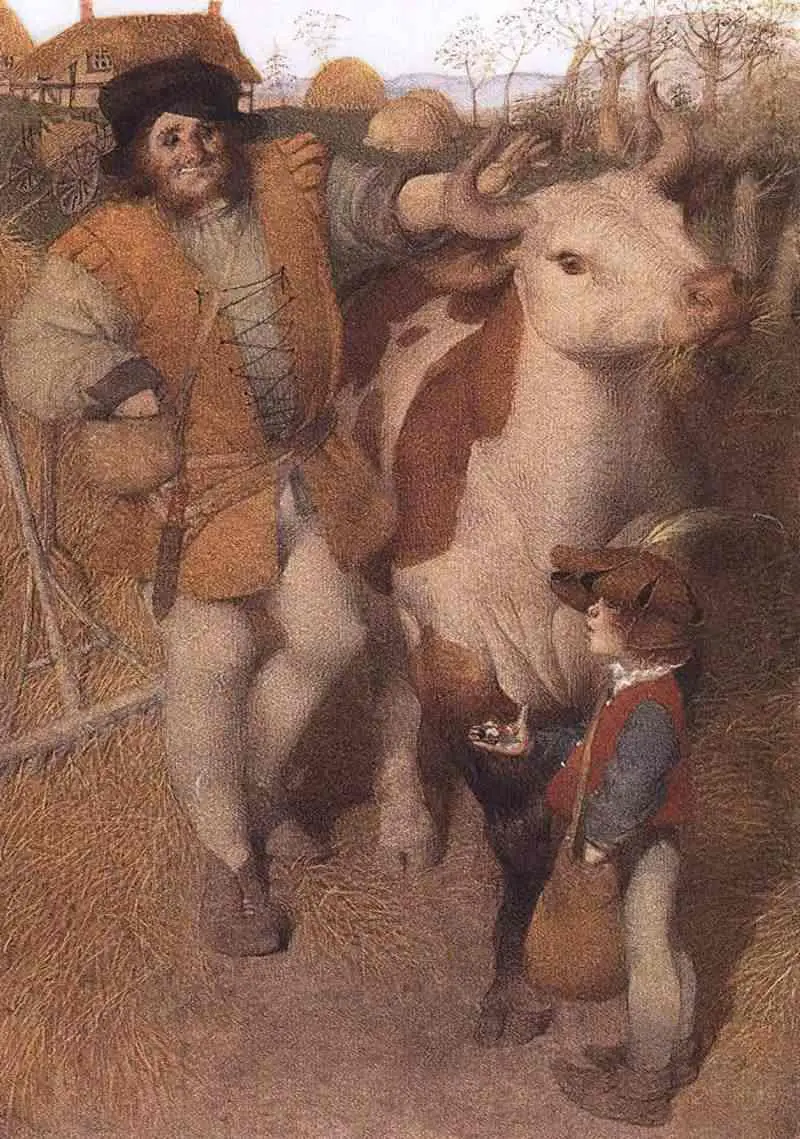

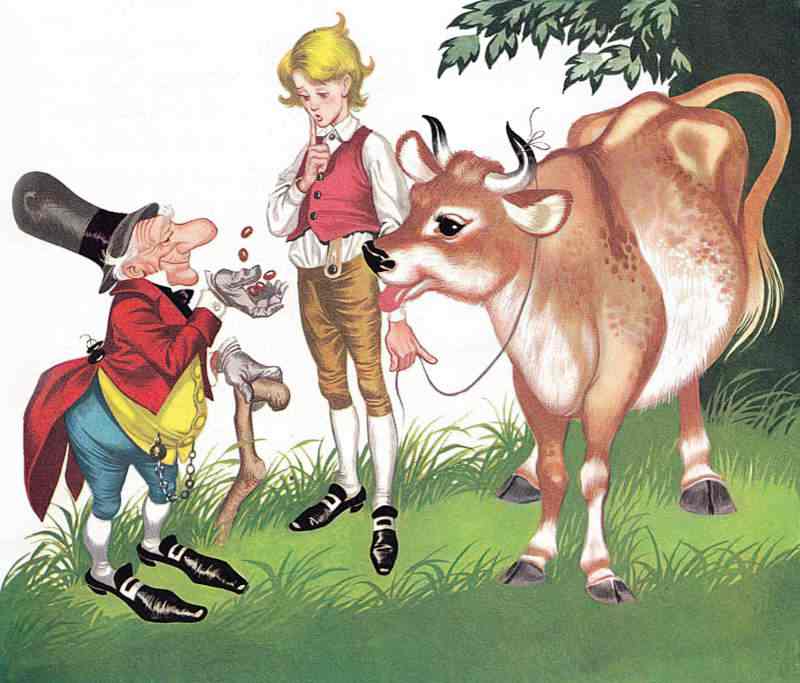

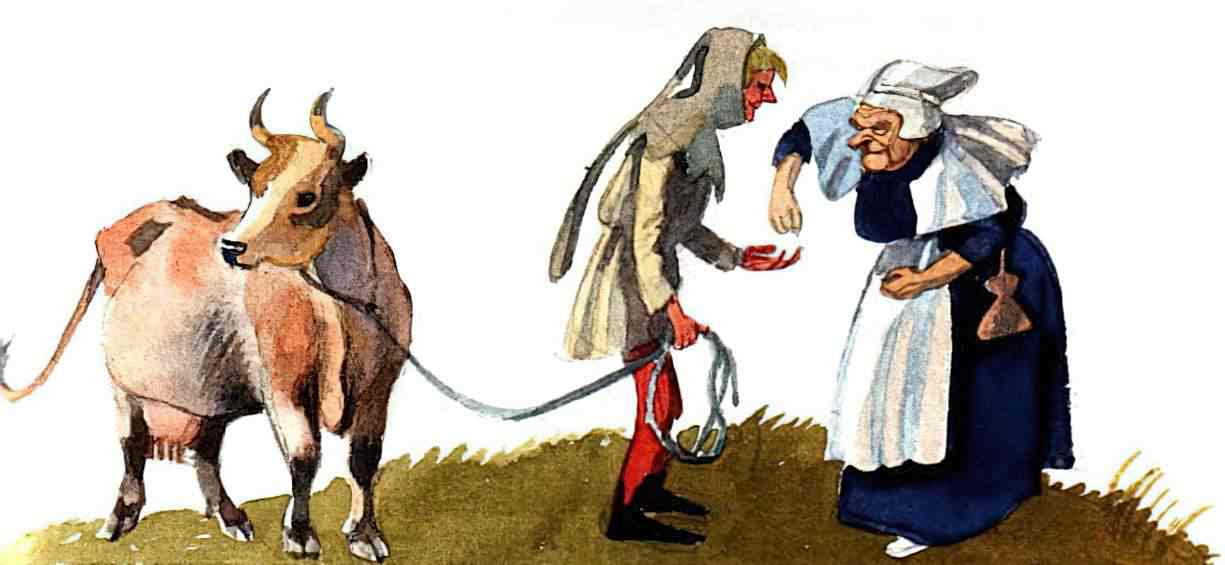

- Down to their last penny, with father dead, Jack’s mother sends him to market to sell Daisy their cow.

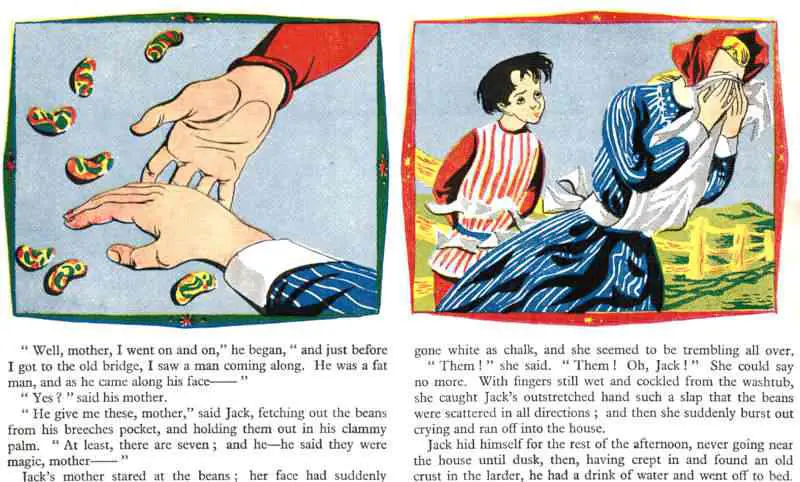

- On the way to market Jack succumbs to a mysterious stranger who offers to swap the cow for some magic beans. Jack’s mum is furious and throws the beans out of the window.

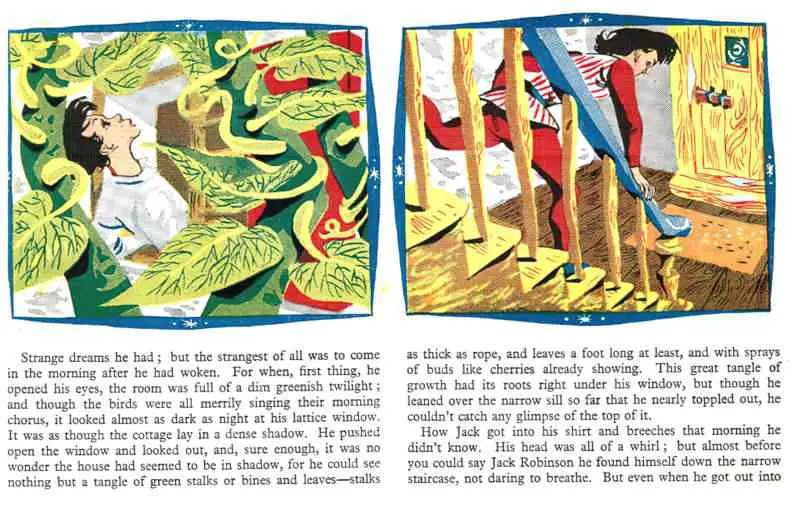

- Overnight a massive beanstalk grows right up into the sky.

Which part is the inciting incident? If one is forced to highlight one single aspect, then inciting incidents are the invitation to leave home and venture into the forest; to reject the thesis of the first stage for the synthesis of the new world. This is where the journey into the woods (or up the beanstalk) begins.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

SHORTCOMING

Jack is easily duped. He also does not have the respect of his mother.

DESIRE

He wishes to please his mother and provide for them both.

OPPONENT

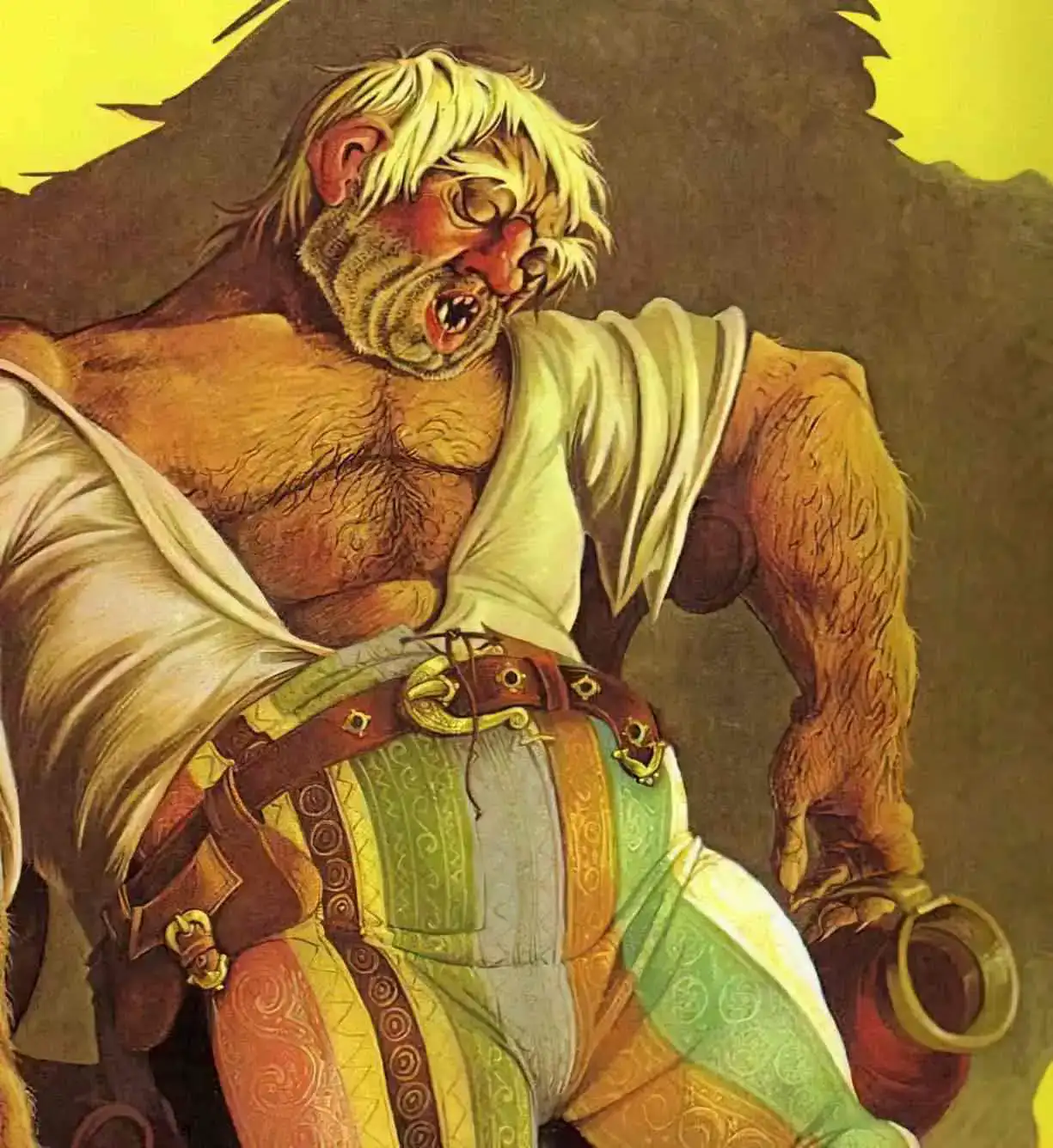

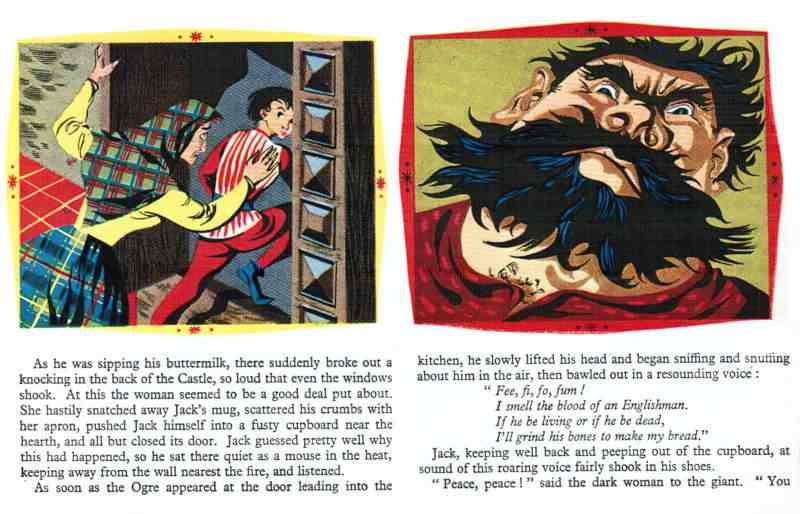

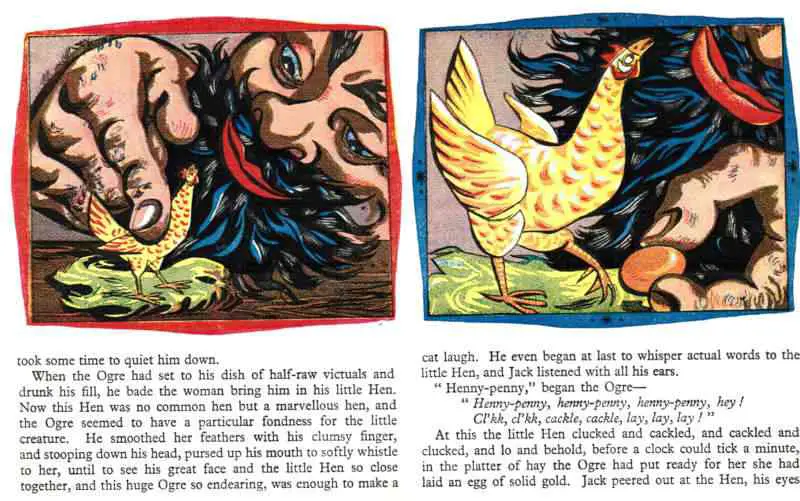

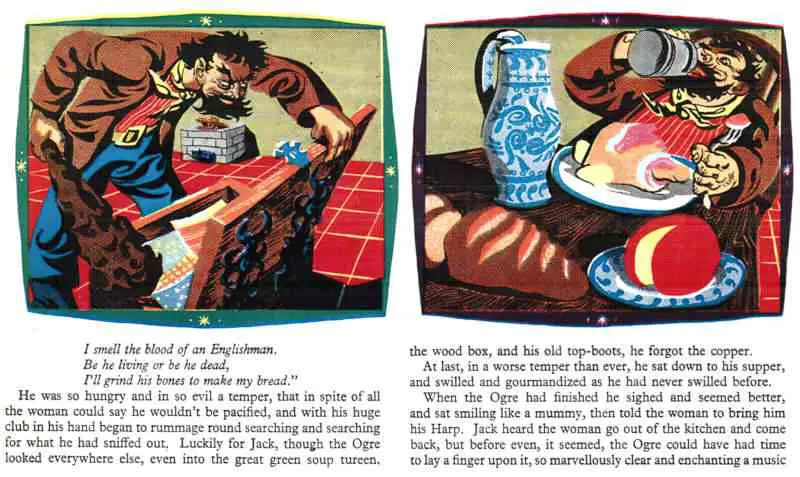

The giant. However, this giant is more properly an ogre.

PLAN

He’ll go to market and sell the cow for lots of money. This plan changes, however, after his mother tells him how stupid he is.

When he sees the beans have grown into a giant stalk reaching up into the sky, now he plans to climb the stalk. He still doesn’t know what’s at the top of this beanstalk. He’s simply ‘curious’.

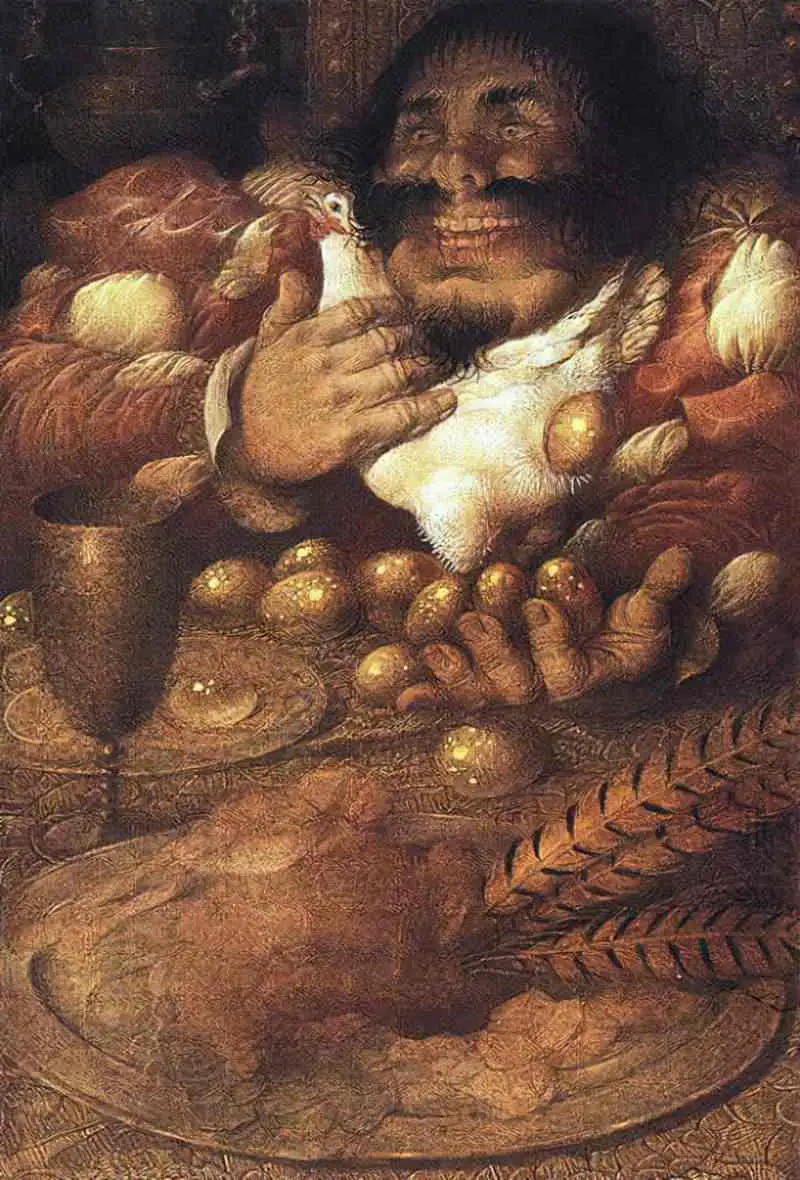

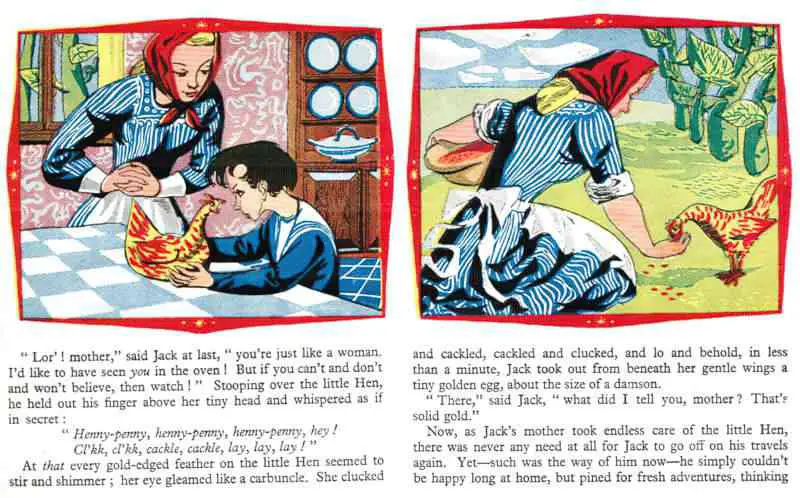

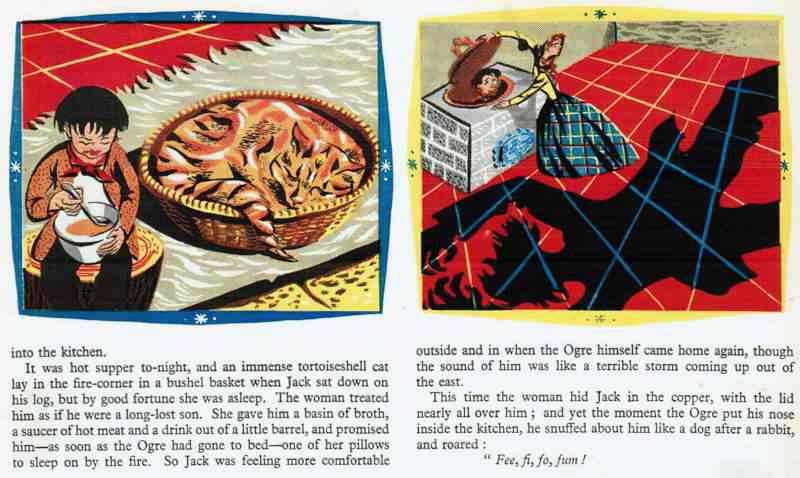

When he sees he can steal a bag of gold and a chicken who lays golden eggs, he plans to take them for himself. This part of the story is quite drawn out in the Grimms’ version; he is quite happy with the gold and the chicken who lays the golden eggs, but has to go back for more thieving after his mother falls ill. He needs something more in order to save her. So he steals the harp, whose music is so beautiful that the mother is restored to full health.

BIG STRUGGLE

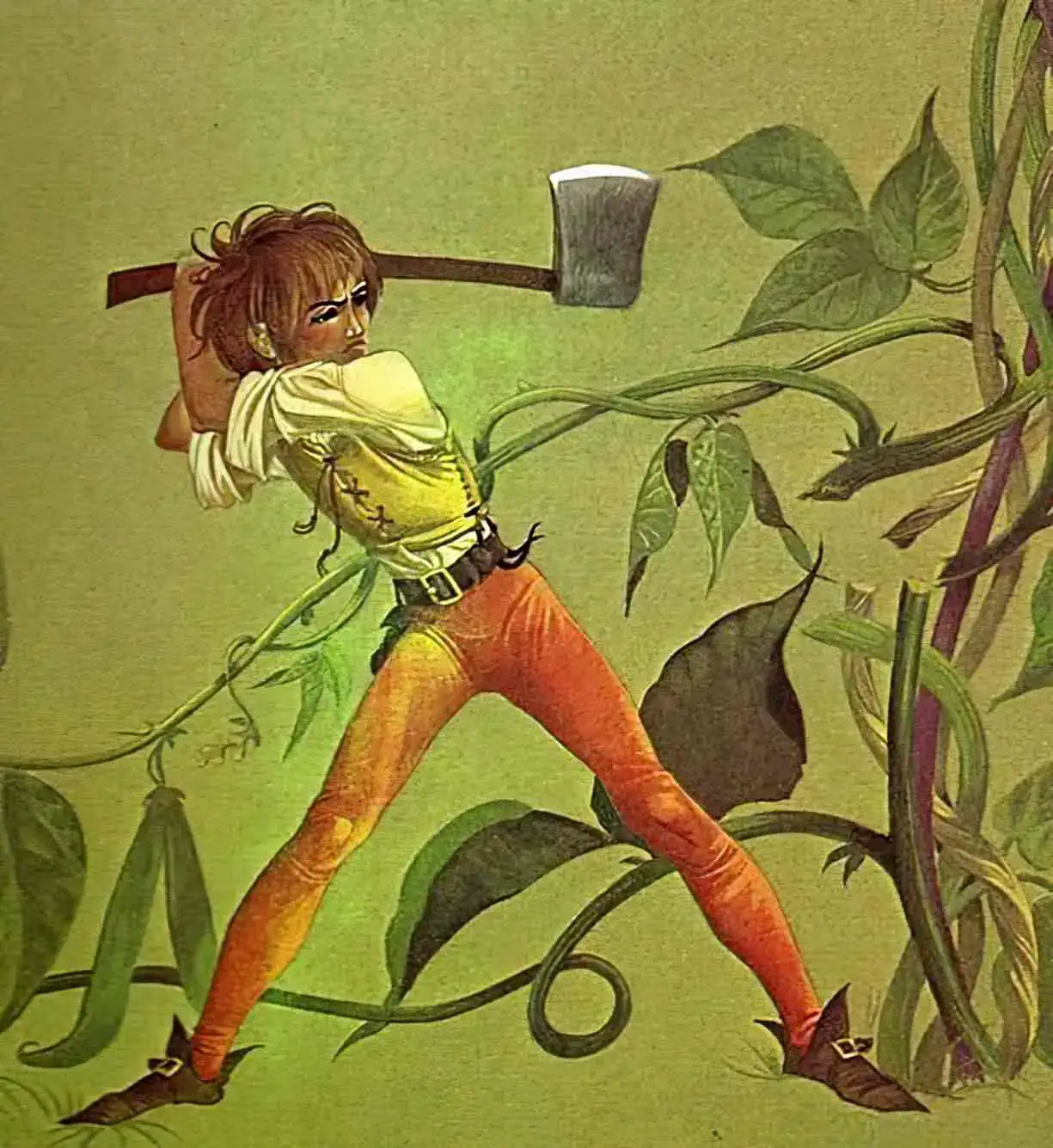

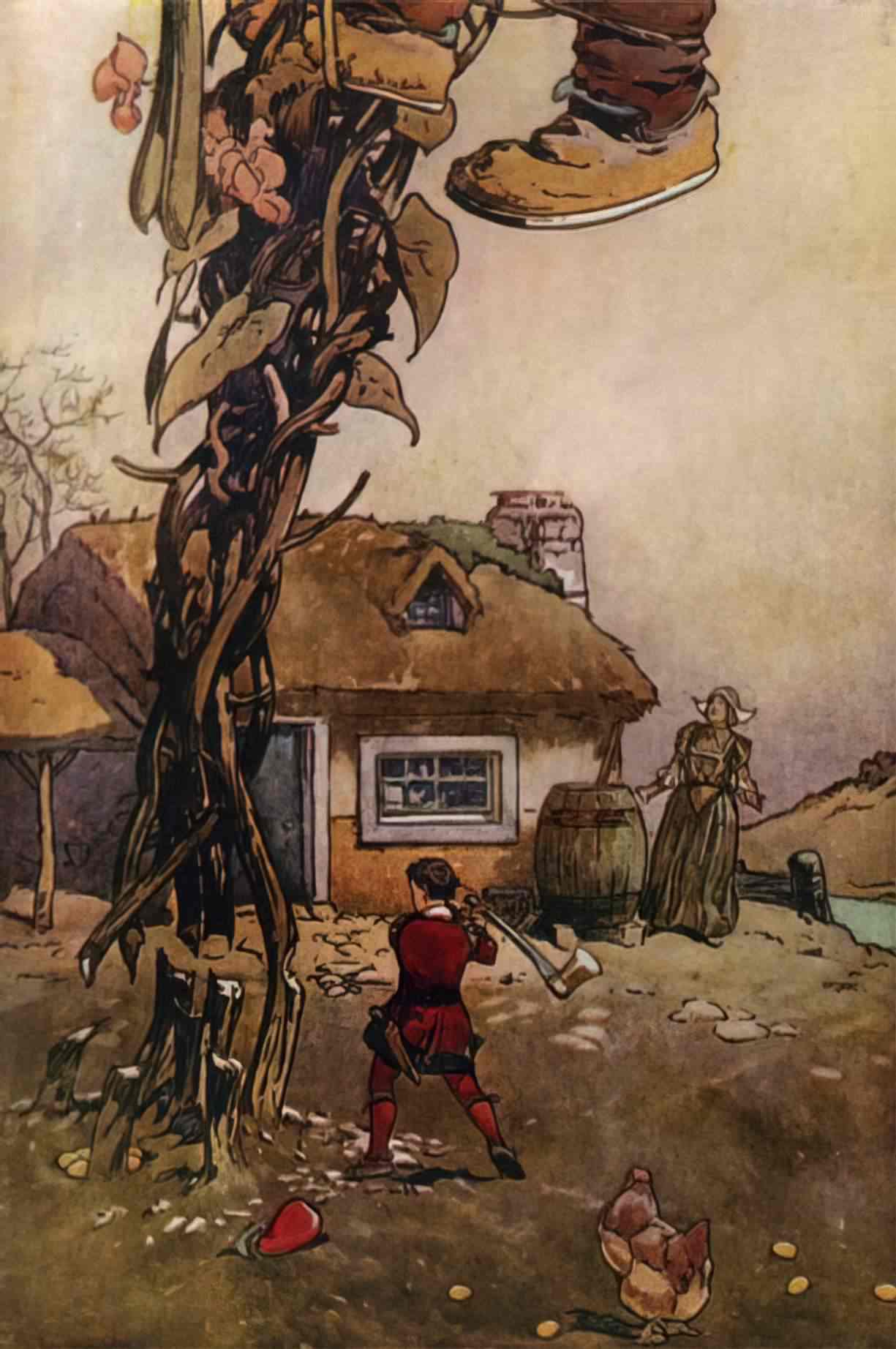

The chase down the beanstalk. The harp is screaming to the ogre. Jack chops the stalk down with an axe before the giant can touch down. If you ever wondered how the two of them disposed of that gigantic body in the yard, the giant conveniently fell down a cliff that was nearby.

ANAGNORISIS

Jack has beaten the giant and is able to provide. Now he can do anything. He is a man.

NEW SITUATION

He lives with his mother in riches for a great number of years and is very happy.

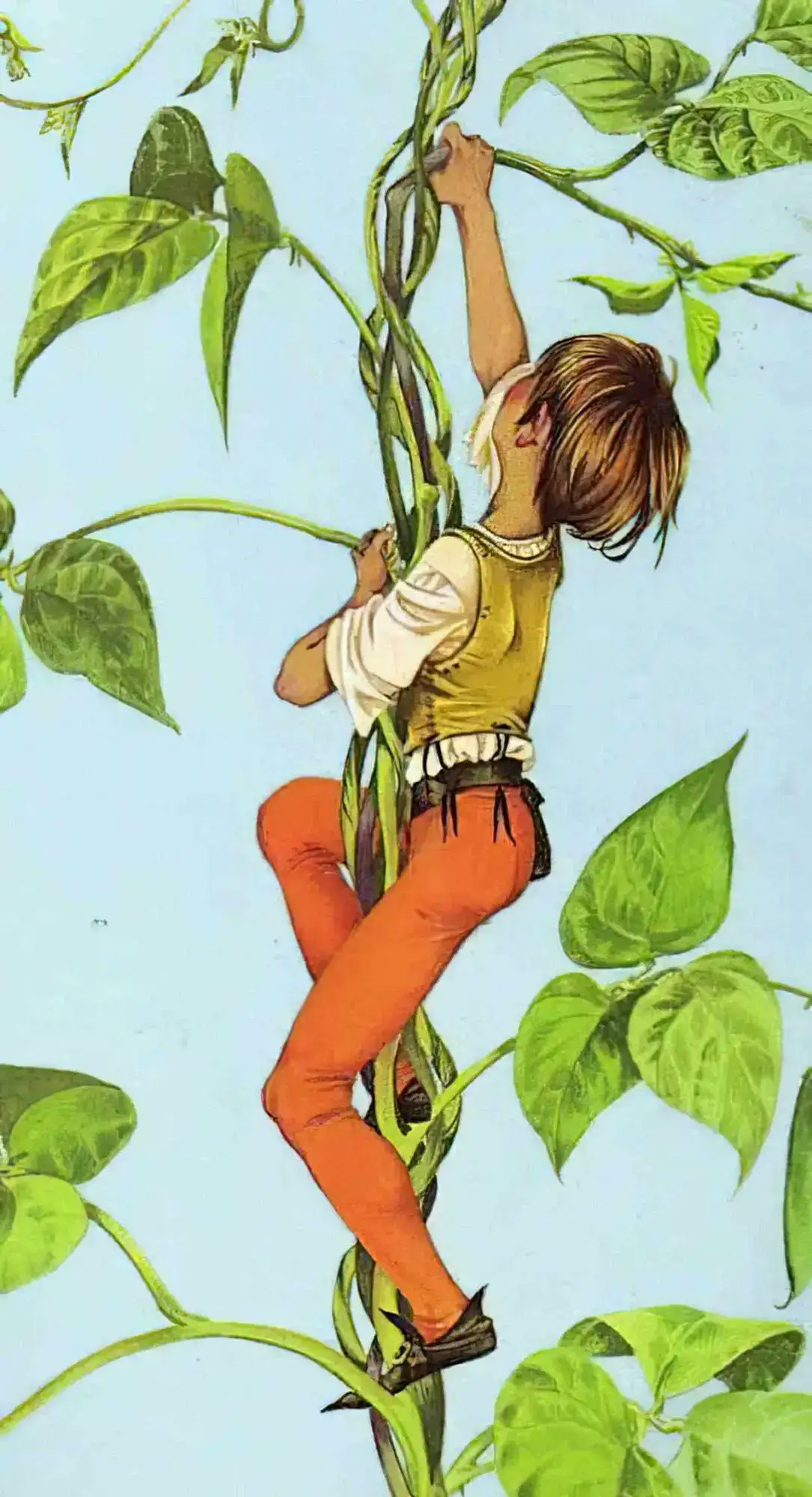

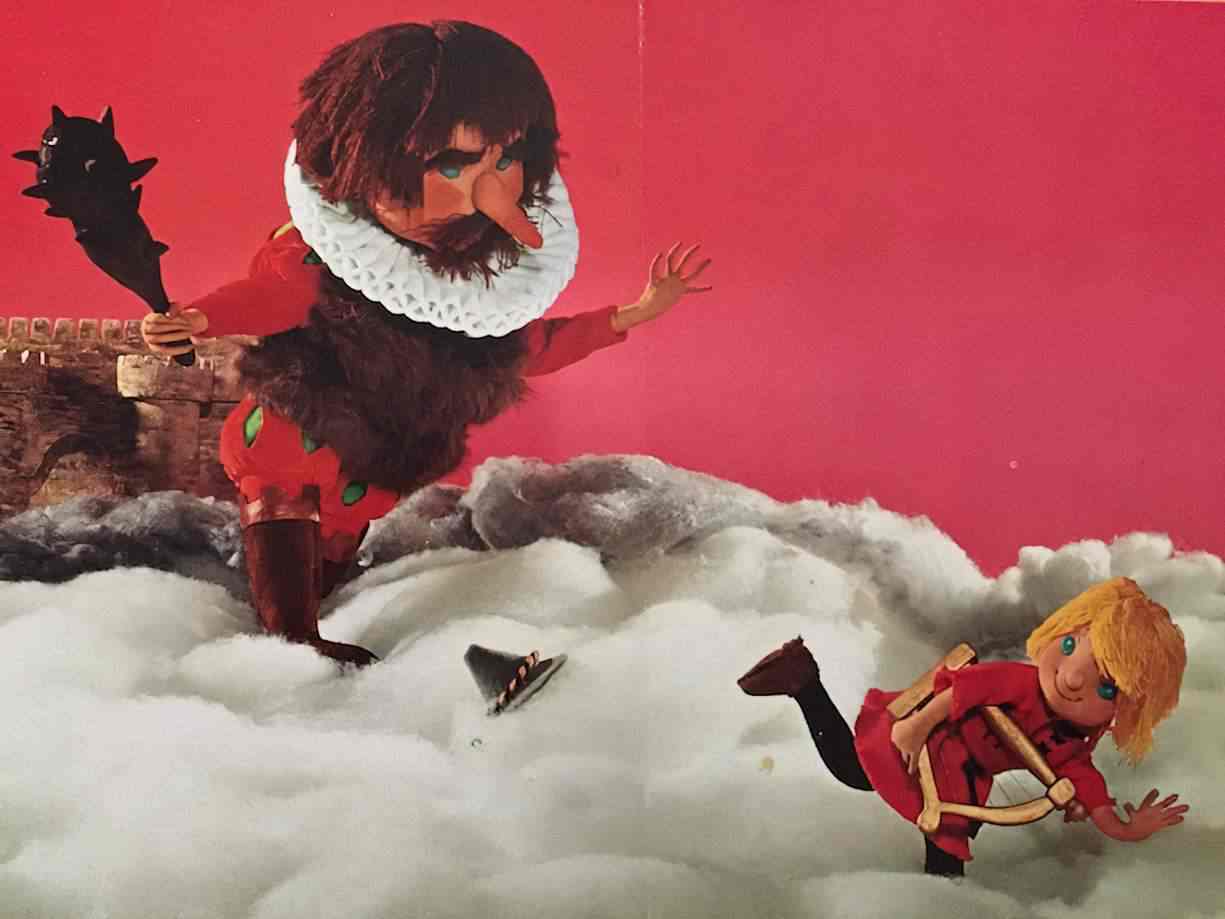

Here is the Froebel-Kan edition of Jack and the Beanstalk that was on our family bookshelf when I was growing up in NZ in the 1980s:

The pictures in this creepy book were done by Rose Art Studios, who I find nothing about online these days. The cover is one of those images — we used to call them ‘holograms’ — which changes slightly when you tilt the book. Inside, the illustrations are photographs of a miniature village which has been modelled; the people are made out of fabric and have wool for hair, while the buildings are basically doll houses. What made it so creepy?

First, the modeller had to decide on Jack’s expression then stick to it, as the same model was photographed throughout. Jack therefore has a creepy and inappropriate smile at every single event.

Second, the publisher couldn’t afford full colour photos on all of the pages, so while some seem saturated, others are black and white, which makes Jack’s eyes look what I’d nowadays describe as ‘like a black-eyed kid’ of the urban legend.

But perhaps even more creepy than those eyes is the image of the feast. I don’t know what they did to make the roast, but that slaughtered animal looks like pure terror.

JACK AND THE BEANSTALK AS HEROIC TALE

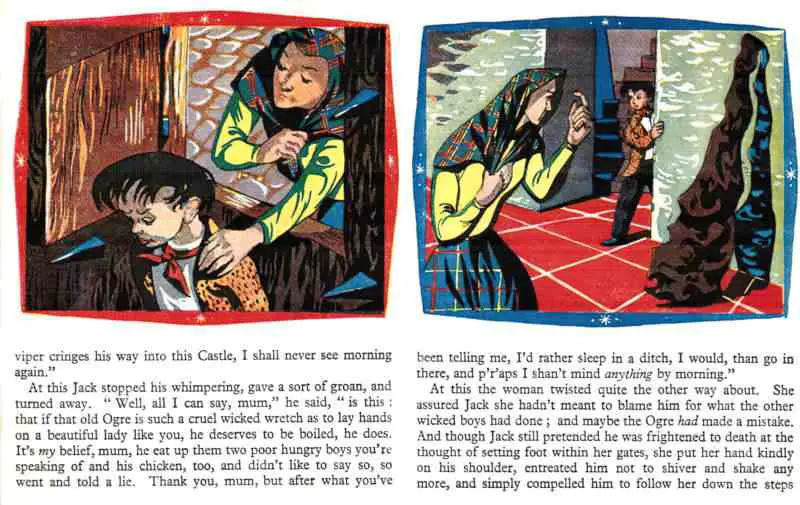

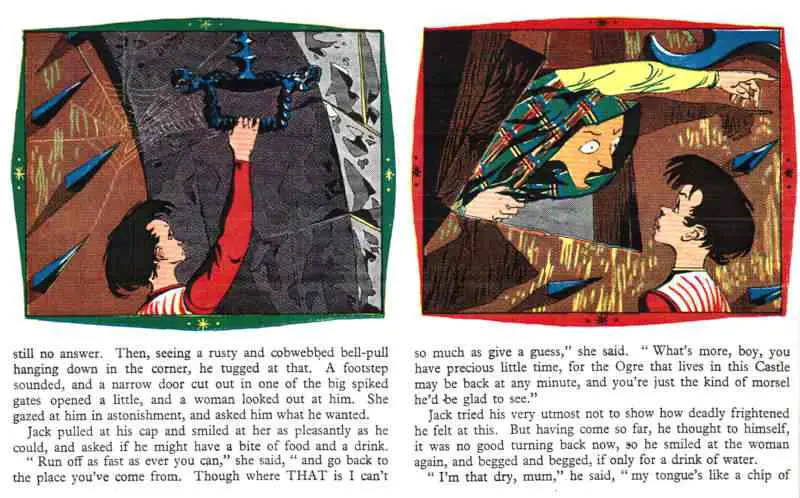

Because hero tales are narrated from the hero’s point of view, and because he occupies the foreground of the story, the reader is invited to share his values and admire his actions, although many heroes do things which most present-day readers would find questionable if they were presented differently. In the English fairy story ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ the narrative point of view requires the reader to approve, or at least condone, criminal and extremely selfish behaviour on the part of the hero. The 1807 [Benjamin] Tabart version of the story, from which later retellings derive, is an omniscient third-person narrative in which the narrator provides information only as it relates to Jack and in which sections of the story are focalized through Jack himself. We see both home, the world on the ground, and the magical world in the sky from his point of view. He is the initiator of the action; it is his decision to swap the cow for the magic beans; he climbs the beanstalk of his own volition on each occasion; he persuades the giant’s wife to admit him, and he decides to steal the hen, the money bags and the harp. The other characters exist only as actors in his story: the two benevolent assistants, the fairy and the giant’s wife, the monstrous giant whom he must overcome, and his mother who is there to welcome him home and reward him with her approval at the end, are all insignificant compared to Jack. Jack not only steals the giant’s possessions, he manipulates and deceives the giant’s kindly wife, who several times saves his life, and finally he abandons her, perhaps to her death, when he cuts down the beanstalk. It requires conscious critical detachment to focus on the sufferings of the giant’s wife for, while reading the story, we are swept alone by its strong forward momentum and controlled by Jack’s perception of things. So it is his initiative, cleverness and success which are foregrounded. It could be argued, following Jack Zipes’s views about the inherent radicalism of folk tales, that Jack’s destruction of the giant is an imaginative depiction of the possibility of overthrowing unjust authority:

the basic nature of the folk tale was connected to the objective ontological situation and dreams of the narrators and their audiences in all age groups…these narratives, even though marked by bourgeois stylization, all retain hope for improving conditions of life and…the fantastic elements (miracles, magic) function to bring about a real fulfillment of the desires of the protagonists who were often underdogs or victims of social injustice.

Zipes, 1979

But if the story does involve an envisioning of successful revolution the image of the new regime which would replace the brutal injustices of aristocratic power is one of ruthlessly laissez-faire opportunism, a restructured patriarchy in which power passes to enterprising entrepreneurs motivated by self-interest, ready to snatch the money and the hen that lays the golden eggs as soon as an opportunity appears.

Deconstructing The Hero, Marjery Hourihan

CHARACTERISATION

JACK

- Fairytales have mostly been considered suitable for children because, like kids, the hero moves from underdog position to powerful.

- This empowerment generally makes them superior to other human beings.

- But they normally have helpers with even stronger powers.

- This is like the child-adult relationship in real life.

- The heroes are not the slightest bit nuanced — they’re 100% heroic.

- The stories are not complex.

- The heroes are not individualized and they all have the same traits: bravery, lack of fear, strength etc.

- These same sorts of heroes can be seen in modern genre fiction for adults: crime, adventure, thriller, romance.

- The hero is more fortunate than ourselves in some way.

- Readers aren’t meant to identify with such heroes. They’re an idealized version of ourselves.

JACK’S MOTHER

The mother is the other side of Jack. She stays in the home while he goes out on an adventure. She mocks his attempt at being a man; he proves he is a provider. Without a female character as contrast, it is harder for the story to be about a very masculine rite of passage. While Jack is heroic, Jack’s mother stays at home weeping, fearing for his safety all the while he’s gone.

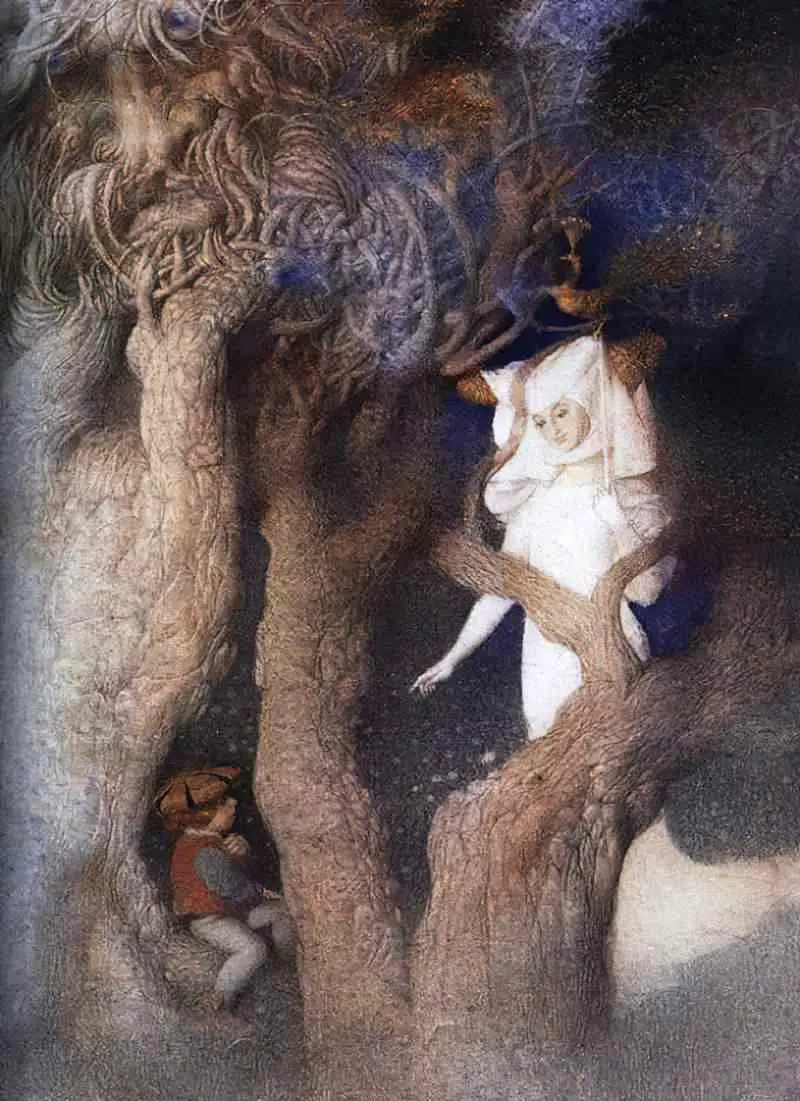

Why is Jack’s mother a widow? In Tabart’s version, the fairy at the top of the beanstalk (often the ogre’s ‘wife’, in later versions) tells Jack about his noble and heroic father who nevertheless got killed by a giant when Jack was only three months old. I suppose this explains why she might think she’d lost her son in the same way.

THE GIANT/OGRE

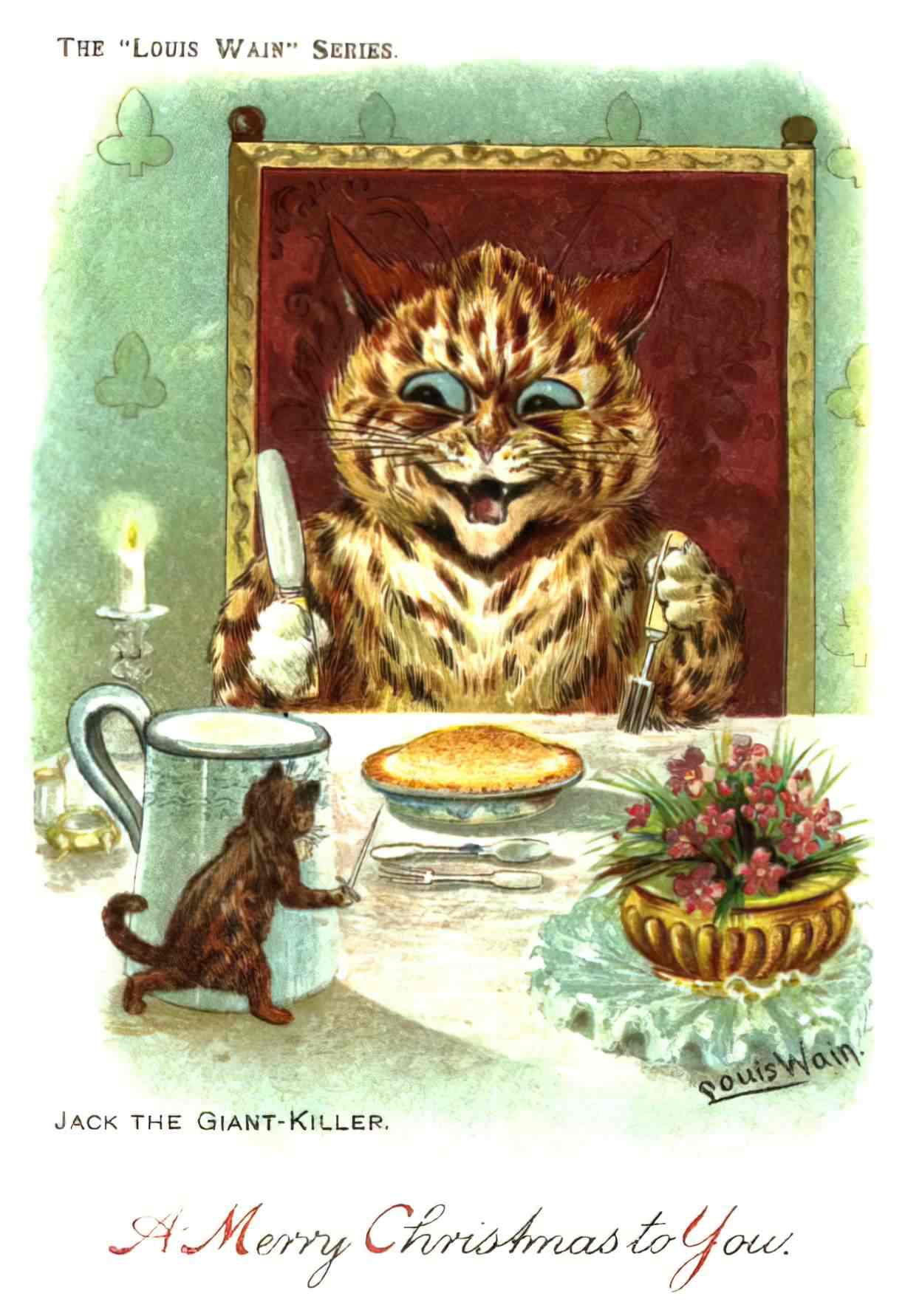

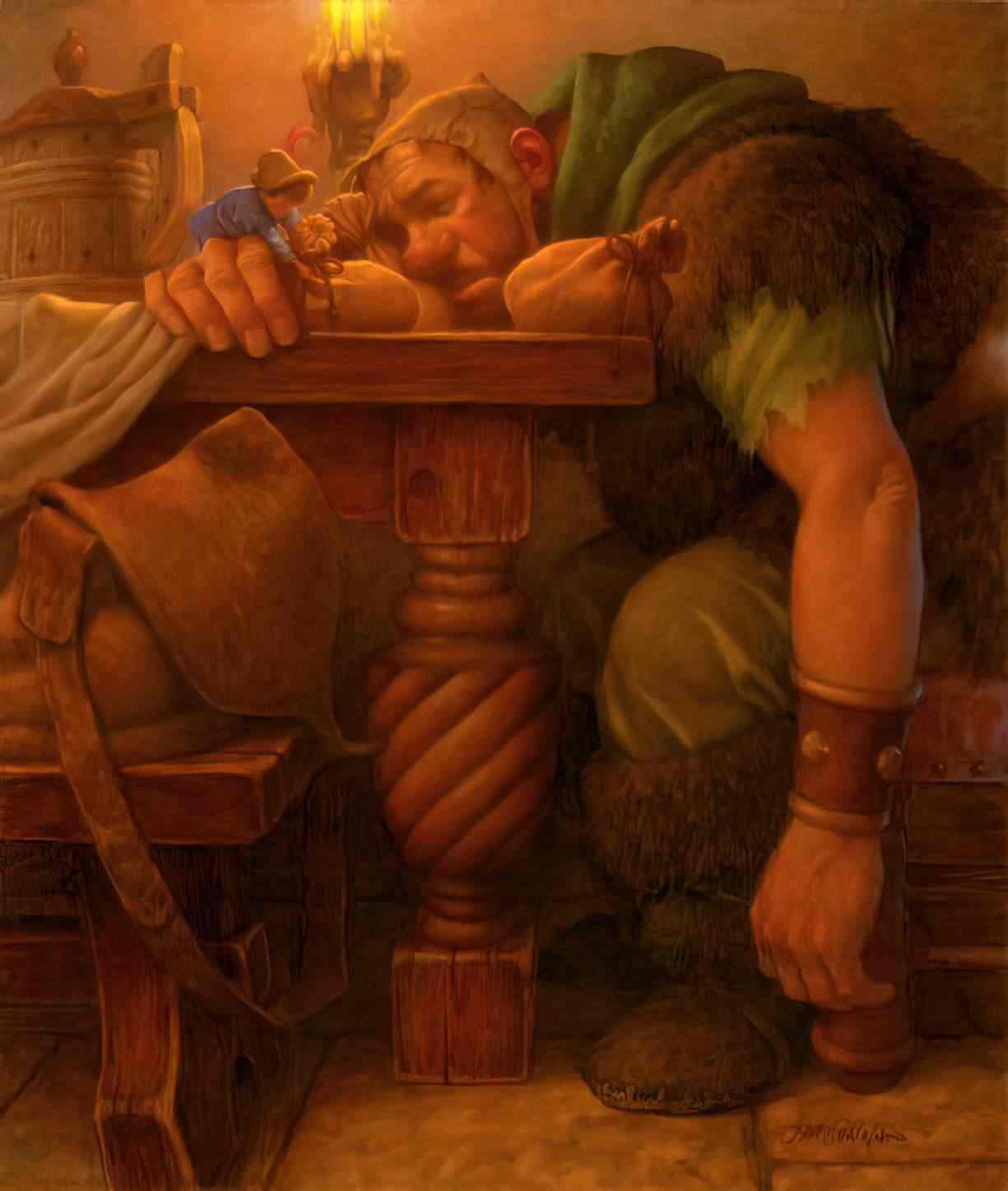

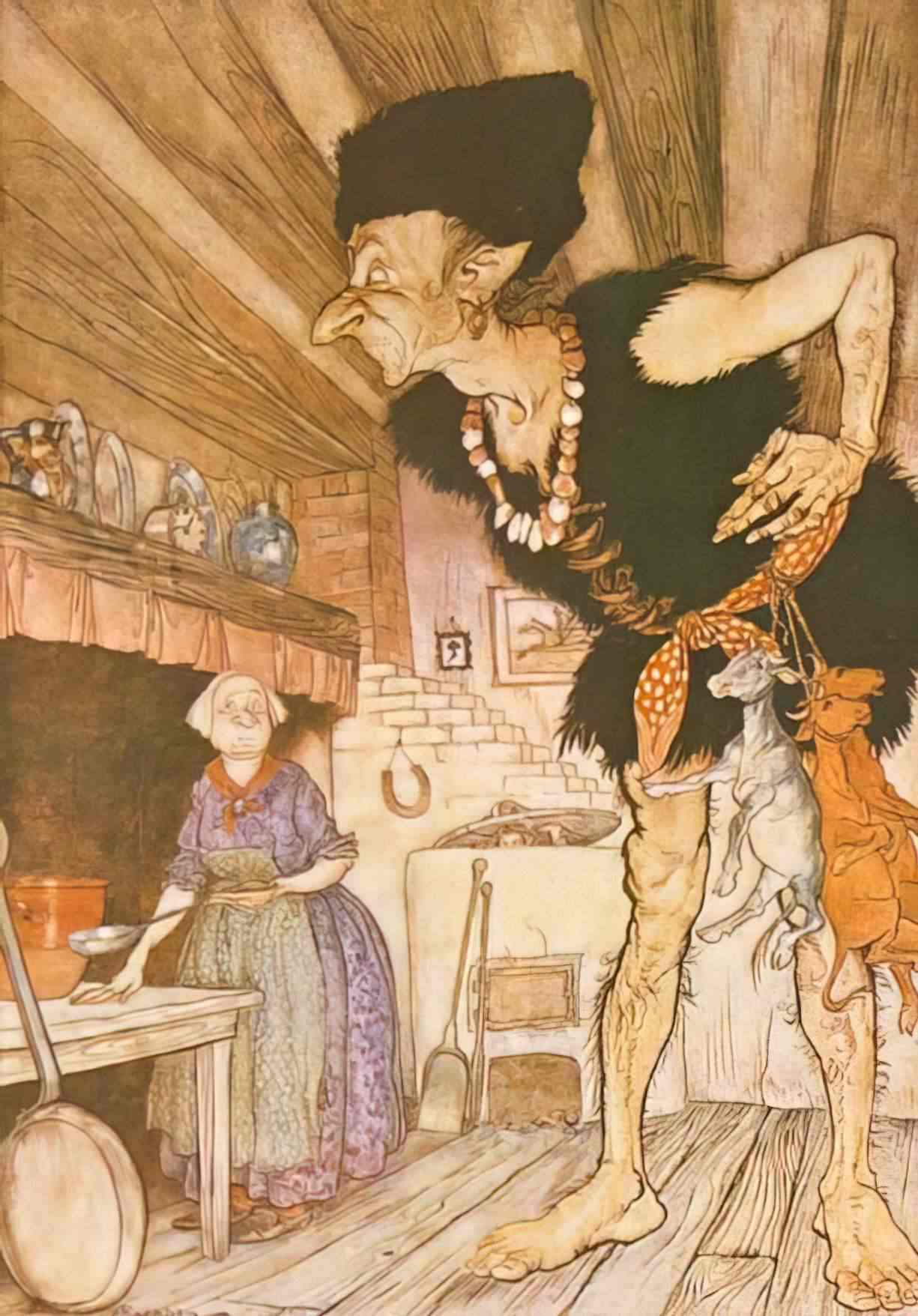

Many illustrators depict the giant as an oversized fool, with a silly and benign grin on his face — even at his enormous size we know he’ll never outwit Jack.

He’s often drawn with a bit of armoury on him. Below, Scott Gustafson has played with the lighting to create an ironically homely atmosphere with orange light.

The Froebel-Kan ogre/giant isn’t all that huge compared to Jack — he can pass as a very large human.

Arthur Rackham, on the other hand, depicts a giant who finds it difficult to live inside his house.

THE BEANSTALK

The Beanstalk and Pagan Belief

A beanstalk growing sky high, overnight, is an example of fairytale magic, but it’s connected to a real-world system of belief which dates from the time of Pythagoras. At the heart of the Pythagorean cult — a pagan religion — was the concept of metempsychosis. This involved the migration of souls from one body to another. Today people think in terms of ‘reincarnation’. What’s this got to do with beans? Well, according to Marina Warner in No Go the Bogeyman, the bean itself might have been transmitted as an intrinsic element in the story of Jack and the Beanstalk on account of its central role in a magical belief system that adhered above all to a vision of natural phenomena as constantly changing from one thing into another—a belief system that governs the realm of fairy tale, as in the case of Jack.

Go back to Ovid’s famous poem, Metamorphoses, which concludes with ‘All things change, but nothing dies. The spirit wanders hither and thither, taking possession of what limbs it pleases, passing from beasts into human bodies, or again our human spirit passes into beasts, but never at any time does it perish.’

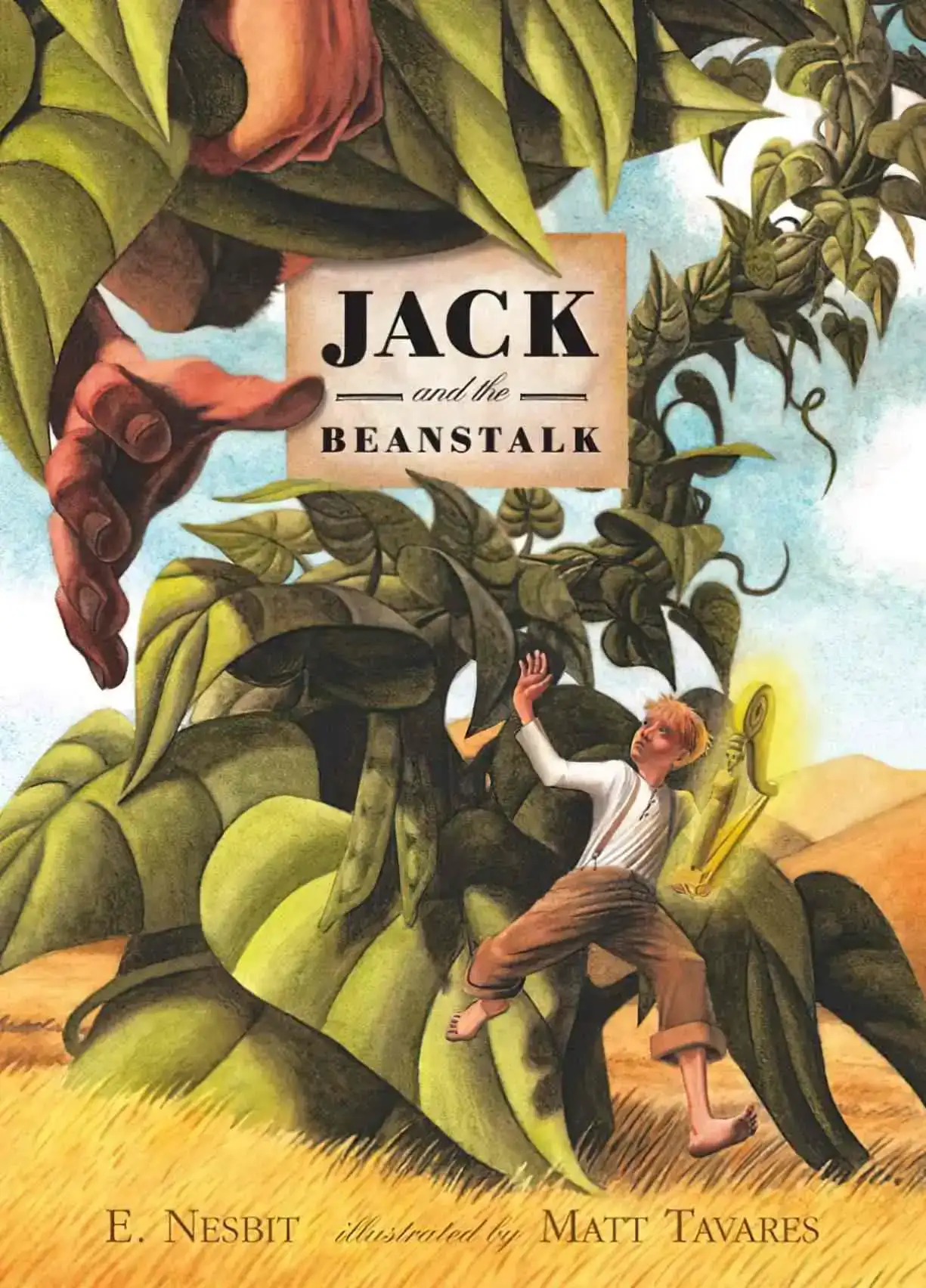

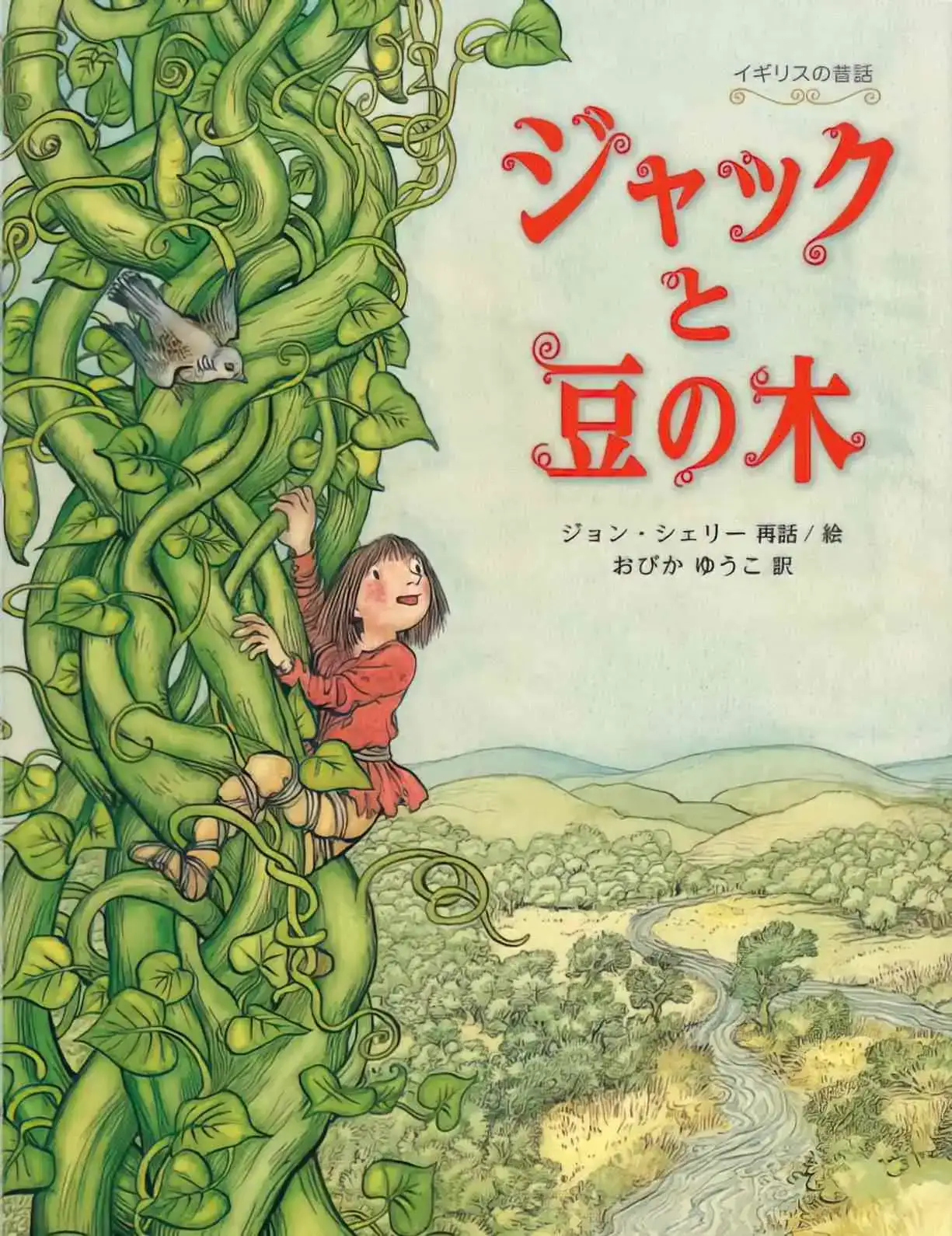

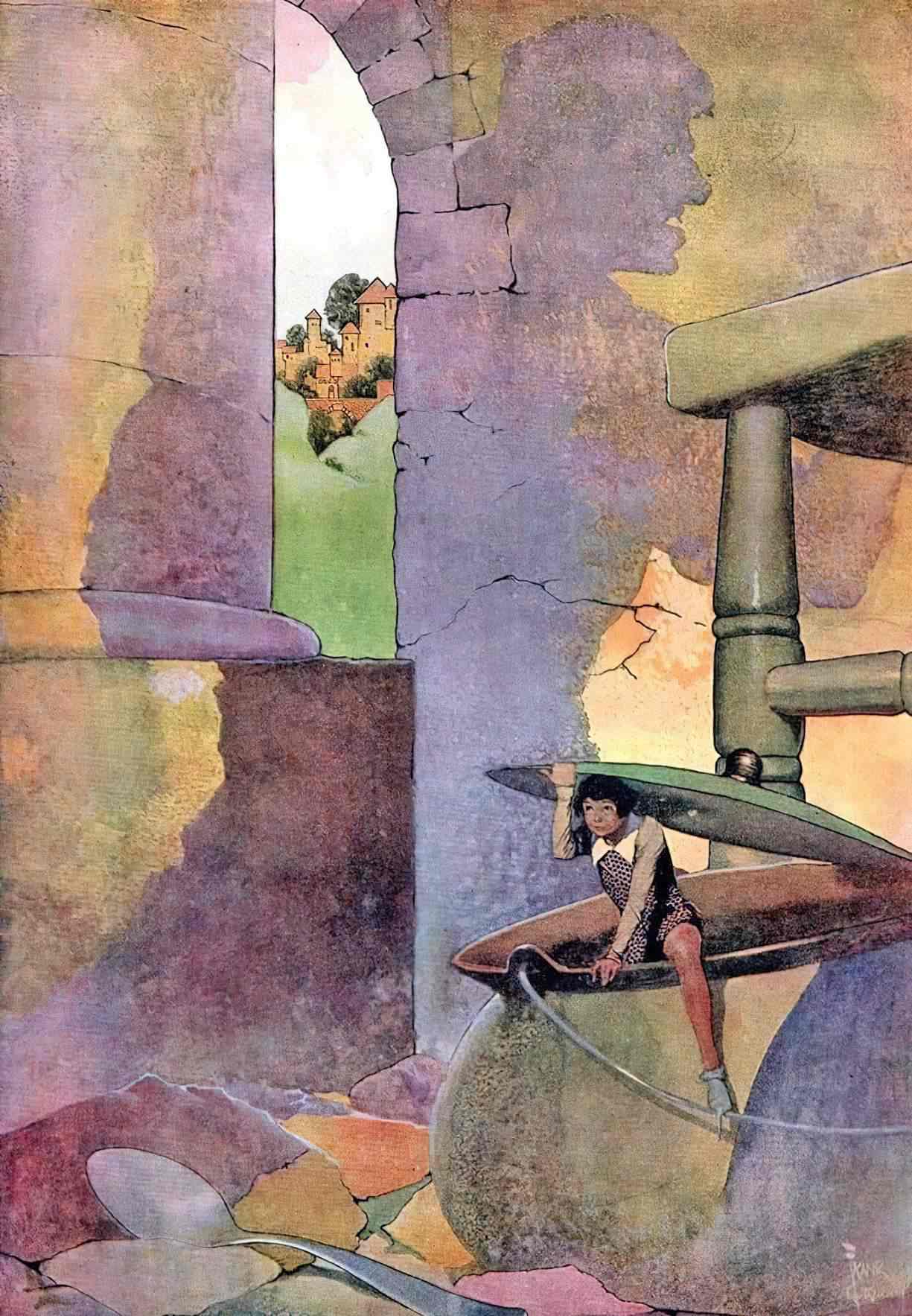

Illustrations of the Beanstalk

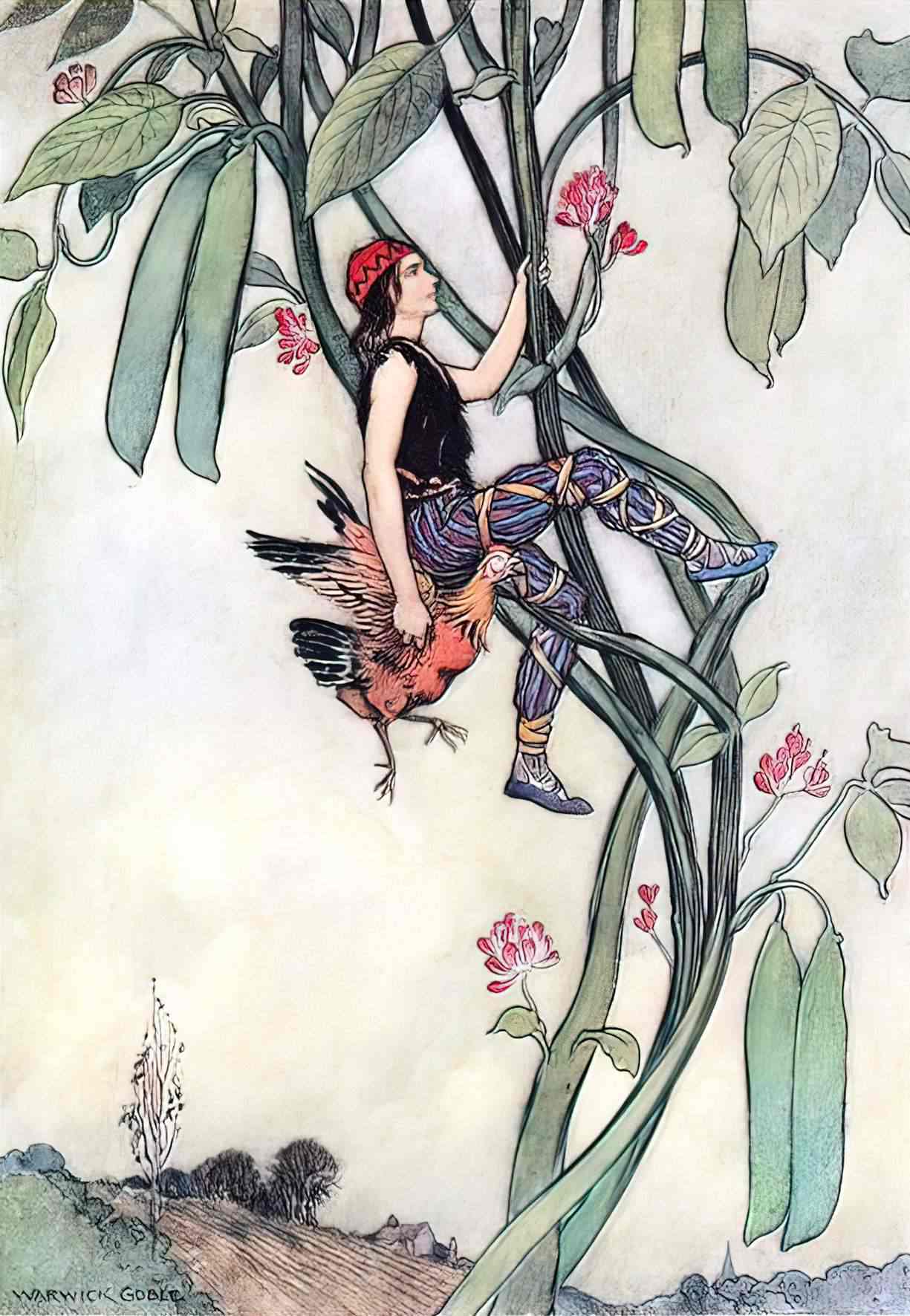

Illustrators have varied widely in their decisions about how to depict the beanstalk. Some choose a low angle view, others high angle, and still others face on, as if we, too, are up the beanstalk with Jack.

The illustration below, by an unknown artist, dates from 1917. As is fairly common in later editions, the giant is only just visible via his feet. When part/most of a scary element is left off the page, this increases the tension and drama.

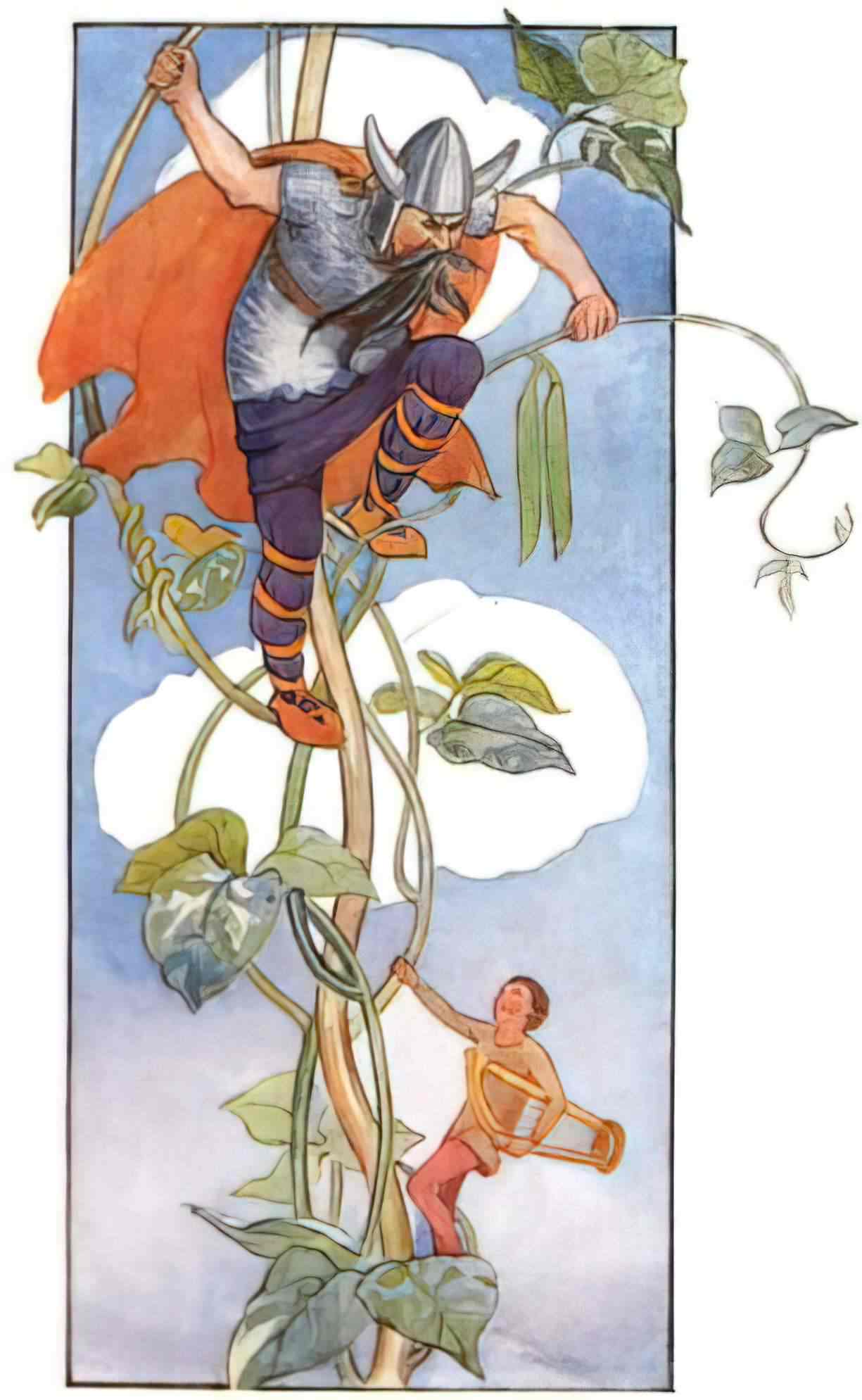

Below, Margaret Tarrant chooses to create a less scary illustration. It’s not just the blue sky, the fluffy clouds and the bright colours; we see ALL of the giant and Jack doesn’t look all that panicked himself.

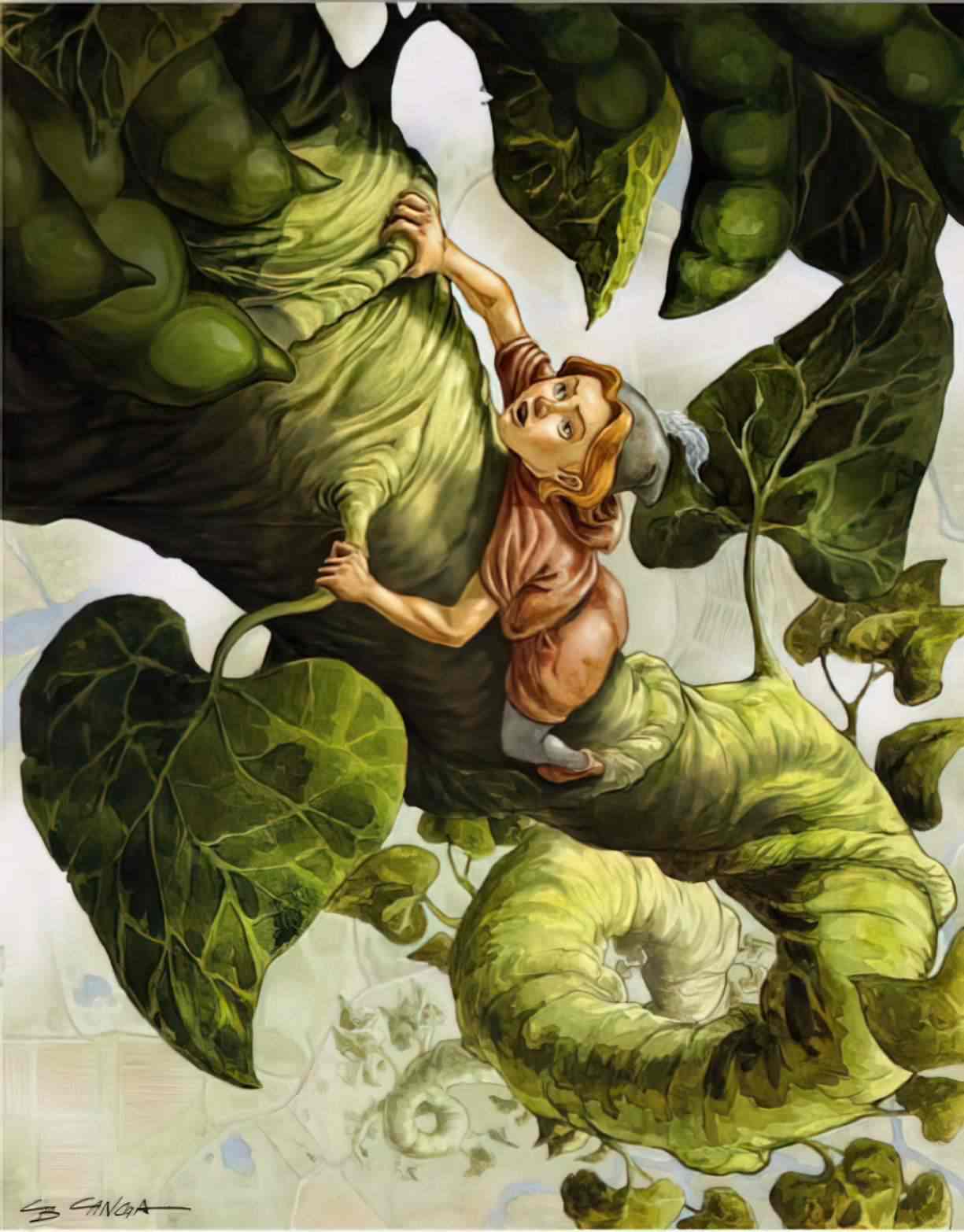

Illustrator Chris Canga has chosen a high-angle view. This view increases the scare factor by emphasising how far Jack has to fall. When choosing this angle the illustrator is able to depict the height — notice how small the fields look below — Jack is as high as an aeroplane flying over land. It’s impossible to convey the height with any other view. Some picture books make it seem as if the giant’s land is not very far up at all.

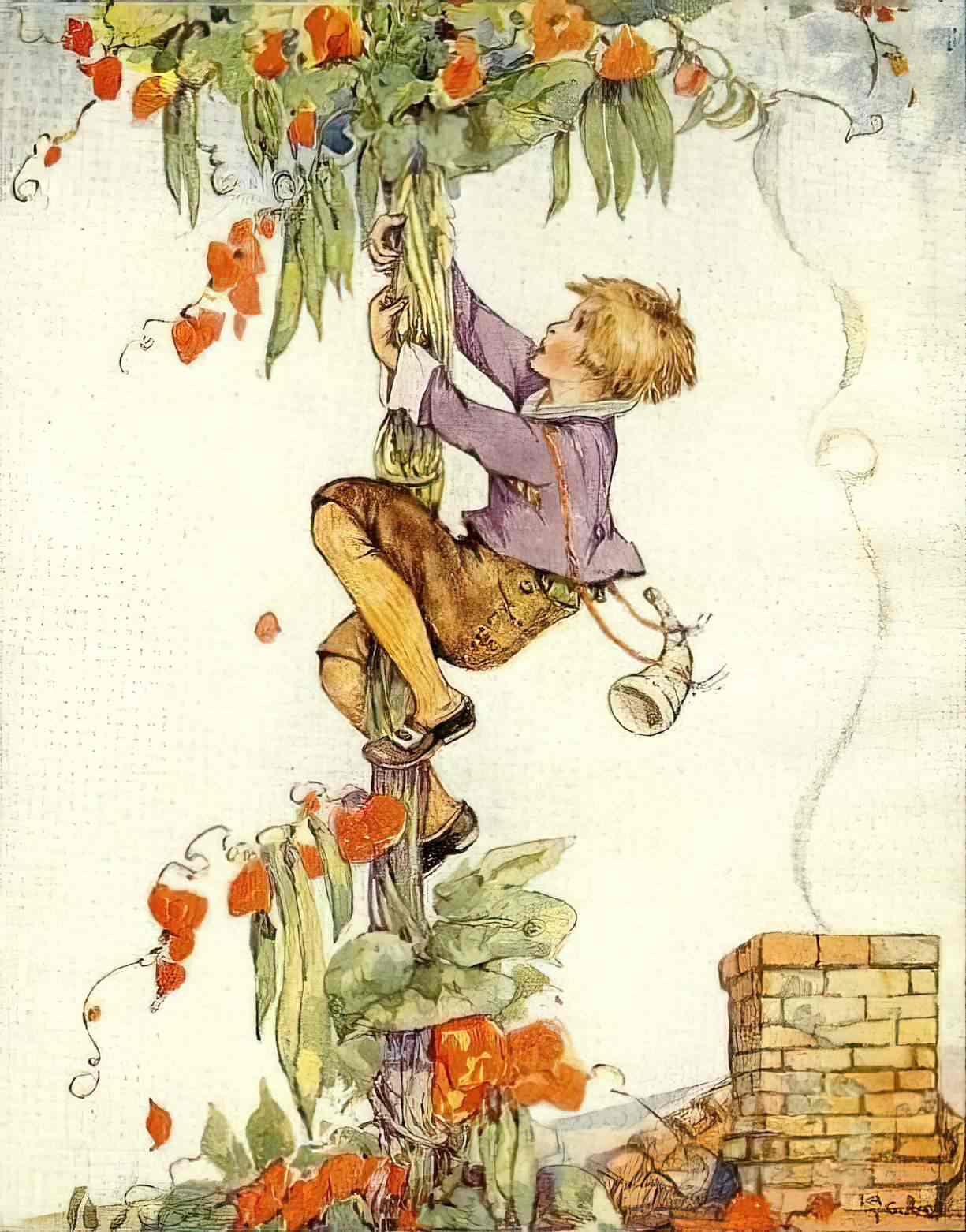

Scott Gustafson manages what’s basically a frontal view as well as scenery which alerts us to the terrifying height. This picture reminds me of illustrations from my version of Enid Blyton’s Magic Faraway Tree series, which was undoubtedly influenced by Jack and the Beanstalk.

This is by Colin Stimpson from his adaptation Jack and the BAKEDbean Stalk (2012). Stimpson has chosen a low angle to emphasise the enormity of the stalk. The beanstalk itself is anthropomorphised — look at how its tendrils clutch the cans as if held in human hands. These tendrils might just as easily catch Jack.

Artist Nick Ainsworth makes full use of an off-page lighting source to heighten the mood. He has played with scale — without the houses below, this enormous beanstalk might look instead like a large tree, or even like a close up of a fairly small one. The composition is nicely balanced with the addition of Jack and his mule in the foreground, who are presumably about to step off a cutbank, or head down into a valley. By positioning the house inside a valley we see a heightened altitudinal juxtaposition: home and Giant-land as opposites.

Most illustrators ignore a detail in an early version of the tale, that the top of the beanstalk is supposed to appear as a desert.

RELATED

Andrew Carnegie & “Jack and the Beanstalk” from Jerry Griswold

Header illustration: Mikhail Bychkov – Jack and the Beanstalk