What might the ‘inverse of a superhero story’ look like? What if superpowers are given to ordinary men who do nothing with them? You may know Christopher Isherwood’s name from the film A Single Man or Christopher and His Kind. I Am Waiting is one of two short stories Isherwood had published in The New Yorker. This one is very much of its era, and must have been written near the time it was published, in 1939 when Isherwood was in his mid-thirties. There are at least two ways of reading this short story: By imagining we are right there with Americans in 1939, or with the benefit of hindsight as readers of the 21st century.

WHAT HAPPENS

It is October 17, 1939. A man in his late middle age reflects on his very ordinary life. But he does have one strange ability: He can jump forward in time. After doing this several times he jumps forward to 1944, where he finds a newspaper. Eagerly wanting to know how the war has panned out, he searches the newspaper for relevant information, but finds only information about chicken breeding.

SETTING

Is Connecticut the default American city where we are to imagine the suburbs — a coathanger of normalcy where strange and disturbing things happen behind closed doors? I have never been to America, but that is my outsider’s view of Connecticut as a fictional setting. This is an upper-middle class household, with a drawing room, tennis court, garden and a maid. These are the sorts of families who holiday at the Cape.

See also: Books set in Connecticut, a Goodreads list. My idea of Connecticut probably derives from the Stepford Wives story.

In this particular story, the setting is even more vital to the plot than the setting, which could have taken place in any American suburb. If you go to a site such as History Orb, you can see exactly what was happening in history in any given month. When this story was published Poland had just been invaded by Germany. Americans — like anyone — would have been anxious to know how the war was going to pan out.

My mind shouted questions: “Had the United States jumped into the war? Had there been a revolution? What is happening in Europe? In China? In the Near East?”

CHARACTERS

The incidents which I am about to describe are true, but I can offer you no proof—at leat not for the next five years.

When a story opens with a first person narrator describing him or herself, the reader’s radar is up: Is this narrator reliable? How well does this narrator know himself? Even if he knows himself, why is he spinning this version of himself for the reader? In this case, though, we are not dealing with an unreliable narrator — this man has reached an age where he has a realistic handle on his own station in life. This story is one of regret rather than boast — perhaps a kind of ‘setting the record straight’ as he heads towards the grave.

We’re more sure of the veracity of his character description because Isherwood drops supporting details into the text. For example, we are told that the narrator keeps himself almost invisible, and this is backed up by the following detail (which is not to say that unreliable narrators can’t be reliably unreliable, but still):

The others had all driven into town to go to a movie, so I could enjoy the luxury of drawing my armchair into the very middle of the hearthrug, facing and monopolizing the fire.

Cast

Wilfred — 67 years old, bachelor, lives in a house owned by his more successful lawyer brother. A self-described semi-educated bore (though he reads Browning) who keeps to himself and pays his way in life with a small inherited income. This is significant because the narrator has even failed to make his mark in life by contributing something to the world in the form of work. His sister-in-law suggests he even wears one of her aprons to search for old photographs in the attic; Wilfred is obviously not considered an alpha male character.

Wilfred’s younger brother — serves as a contrast to the narrator as a ‘successful and energetic lawyer’. His three male sons only add to his aura of social success. But this is not a Cain and Abel archetype; most sibling relationships in real life are less dramatic than that:

From boyhood I have admired, though somewhat grudgingly, the extreme lucidity of my brother’s intelligence. Now, as I stood there baffled, I asked myself what would he, who was never at a loss, have done in my place.

Mabel — the younger brother’s wife, very kind to her brother-in-law ‘on the whole, as long as I am careful to be tidy and not unnecessarily visible’.

Three nephews — sons of the lawyer and Mabel. All grown with wives of their own; all have moved out of the natal home. These nephews are mentioned as a way of populating the story with a believable family network.

THEME

In late middle age we sometimes realise our extraordinary talents may come to nothing much after all.

Maria Nikolajeva writes of children’s literature specifically when she describes the general function of time travel in fiction, but if we can make any generalisations about the time travel in general fiction, the ability to travel through time is generally for some higher purpose:

Today we read that the whole purpose of time travel is to change history, either the private history of the character, as in Playing Beatie Bow (1980) by the Australian author Ruth Park, or The Root Cellar (1981) by Canadian Janet Lunn, or the history of the world, like A Swiftly Tilting Planet (1978) by Madeleine L’Engle. In this book the character changes the past so that the third world war does not break out in his own time. Time Travelers are no longer passive observers, but must take upon themselves responsibility for their actions in the past.

Children’s Literature Comes Of Age by Maria Nikolajeva

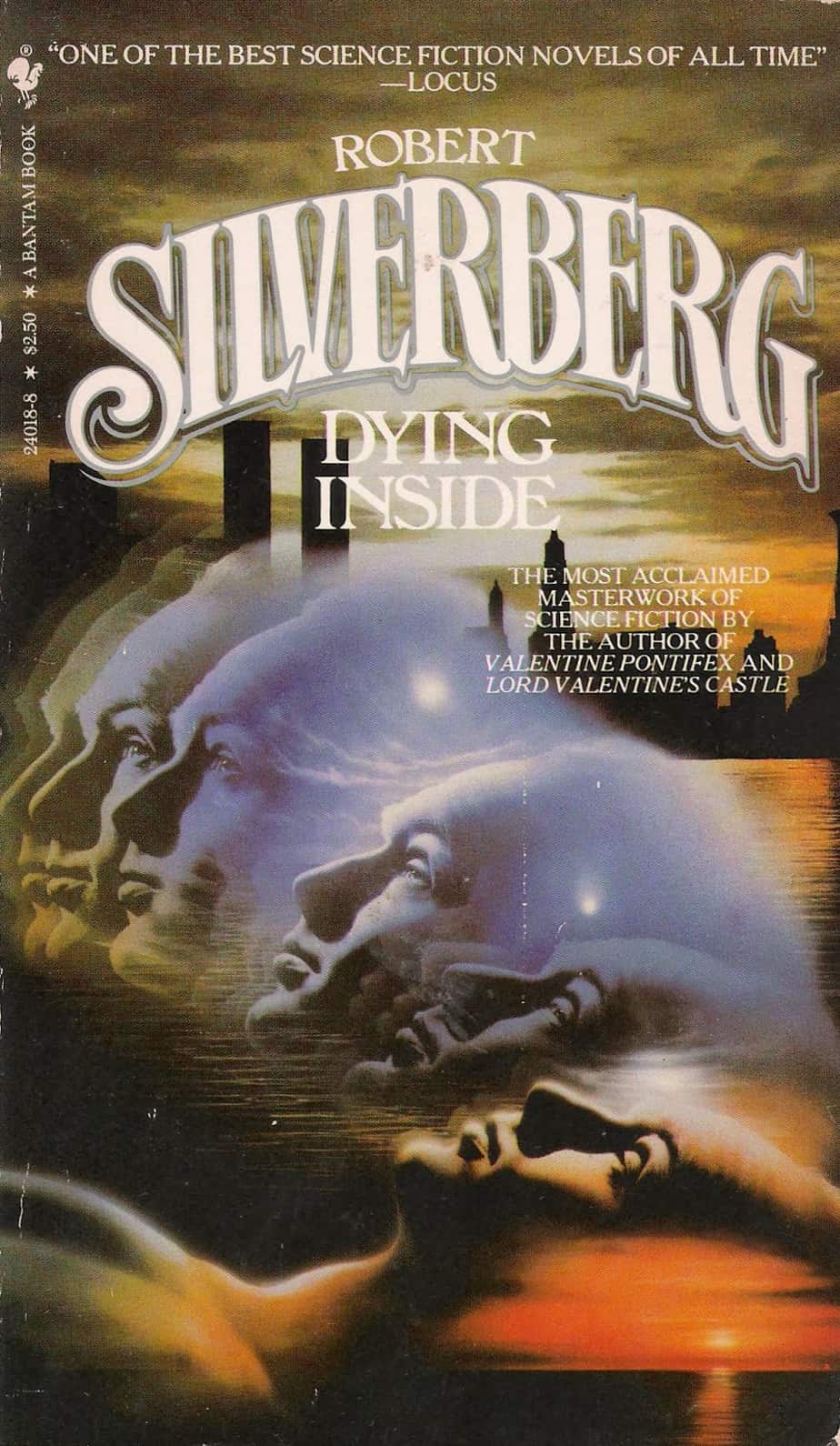

However, in Isherwood’s short story, the ability to time travel is remarkable, but because the man who has this ability is so very unremarkable, nothing comes of it. What if he had learned something about historical events? What could a retired bachelor living in his brother’s house in Connecticut really do about any of it? The war was so much bigger than one man, let alone this particular man.

Anyone who has seen/read A Single Man (starring Colin Firth) or Christopher And His Kind (the biography of Christopher Isherwood) may find it hard to put aside the knowledge that Isherwood was a gay icon. Though Isherwood embraced his sexuality, he lived at a time when many gay people could not. Is the bachelor of this story gay? If so, he has spent his entire life failing to live up to his potential. The following is from the initial paragraph of the story and otherwise feels apropos of nothing:

I have never married and I cannot truthfully say that I have ever been loved, though half a dozen people are, perhaps, mildly fond of me.

Reading from a modern perspective, if only men such as this narrator could have time traveled forward another few generations, their lives would have been much different. The benefit of modern hindsight aside, this is a story about a failed superhero. What if the powers of Superman had been gifted to a repressed character and come to nothing at all? How many Supermen are out there, hiding almost invisibly in suburban rooms?

See also: Time Travel In Fiction

The unknown future is scary, but there is absolutely nothing to do but wait and see.

Though this character is facing the challenges of old age, even the young are now faced with thoughts about their own mortality. In wartime, every age shares this in common.

And now here I am, waiting for whatever may come next. Sometimes I feel frightened, but in general I managed to regard the whole business quite philosophically. I am well aware that the next adventure—if there ever is another—may be my last…let the moment call for me when it will—at whatever time, in whatever place. I shall be ready.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

Realistic Character Memory Of Dates

When a first person narrator remembers a date, it helps to make that date somewhat significant. People don’t tend to naturally remember dates of events unless they happen on a holiday or anniversary:

On the evening of Friday, January 6th, of this year — I can be exact, for this was the day after the anniversary of my brother’s marriage—I was sitting in the drawing room of our house…

Two brothers: One successful, one a failure

This character ensemble is utilised to highlight the sad life of the narrator. One brother is heterosexual and therefore privileged, with a great job and three sons (the epitome of familial success), contrasted against the bachelor younger brother who is without valued achievements.

The drawing room clock is supported by a pair of china figurines. When Annie breaks the china boy’s left hand off at the wrist, this imagery would be familiar to those who saw men come back from the first world war with amputated limbs and disturbing disfigurements. The narrator refers to the broken figurine as ‘the mutilated boy’. In 1939, American readers would have been worried that this scenario would happen again, and no one could predict the extent of human damage.

When Wilfred stumbles upon a newspaper, it is significant that he has stumbled upon The Cage Bird Fancier. Wilfred himself is, at the time, locked in an attic in a house in the suburbs, in a country which may or may not go to war. Much like a caged bird, in fact.

The first time travel incident is astonishing; the second sets up a pattern; the third forms the meat of the story. This is such a commonly used narrative technique that it takes a brave writer to fiddle with it. Each incident is accompanied by an increasing amount of detail.

Detail To Accompany The Magical Realism

Fantasy lovers can avoid this term, preferring simple ‘fantasy’ to describe this kind of story — a realistic story with a little bit of impossible stuff going on. To make the concept of time travel believable within the world of the story, Isherwood has included a significant amount of detail: The characters, how they are related to each other, the snippets of dialogue from the tennis court, the weather. The book he is reading, where he is sitting in his chair. The direction he moves in (‘toward the bookcase’). A lot of this detail exists to provide verisimilitude. The author also relies upon the fact that at times of great stress or inner turmoil, people tend to remember details we may not otherwise:

I read on and on, learning all manner of highly relevant and unfruitful fact…These tiresome details are imprinted upon my memory forever.

Chickens are great for this purpose, and are used here to good effect. Though the whole world is entering a war, the newspaper reports on chicken breeding. Irony is a meaningful gap between expectation and outcome. Once understanding that this ordinary man has an extraordinary gift, we expect something to come of it, but nothing does. This is a form of ‘presentation irony’, and also may be considered ‘genre subversion’, since superheroes tend to save the world from disaster.

STORY SPECS

First published October 21, 1939 in The New Yorker

Available today in The New Yorker’s archive viewer (with a pay wall)

Collected in Short Stories From The New Yorker, published 1940

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Compare

A commenter at The Mookse and the Gripes blog suggests a thematic comparison to I Am Waiting:

Contrast

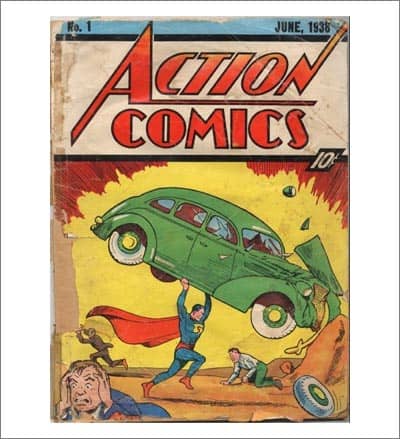

The perfect contrast is against Superman, which was new and popular at this exact time in American history. Everyone was wishing some superhero could swoop down from on high and save the world:

Superman is a fictional superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. Superman is widely considered an American cultural icon. The Superman character was created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, high school students living in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1933; the character was sold to Detective Comics, Inc. (later DC Comics) in 1938.

WRITE YOUR OWN

If you discovered you had a secret superpower, what might that be?

And given your life circumstances, what would you — in reality — be able to accomplish with it?

What would a duller, less successful version of yourself look like? And what if that character had the superpower instead of you?