In “Clancy in the Tower of Babel” (1953), Cheever dealt with homosexuality overtly for the first time. But his treatment is stereotypical; he portrays his homosexual characters as effeminate, hysterical, and tortured.

glbtq

It’s difficult to read the stories of John Cheever without taking what you know of the author’s life as a palimpsest for his characterisations. Though I’m interested in reading one of the biographies, I’m deliberately holding off until I’ve finished his collected short stories, but even the most rudimentary look into the life of the author soon highlights his bisexuality as influential in the themes of his work.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “CLANCY IN THE TOWER OF BABEL”

An Irish immigrant to New York has an accident at his labouring job and eventually finds a job as an elevator operator at a nearby apartment block which, despite its geographic proximity, is completely foreign to Clancy, and his simple life which is in many ways humble. He gets to know the people who come and go, and eventually learns that one of the men is gay. He is disgusted when this man brings back a male lover, and refuses to take them down in the elevator.

After the gay man tries to gas himself in his oven, get Clancy fired, get Clancy back etc etc, Clancy has a sort of epiphany at the end of the story when he realises that, however much he loves his wife and son, to others they would not seem perfect.

SETTING

New York, first half of the 20th Century, exact year not clear — perhaps set in 1951, the year it was published.

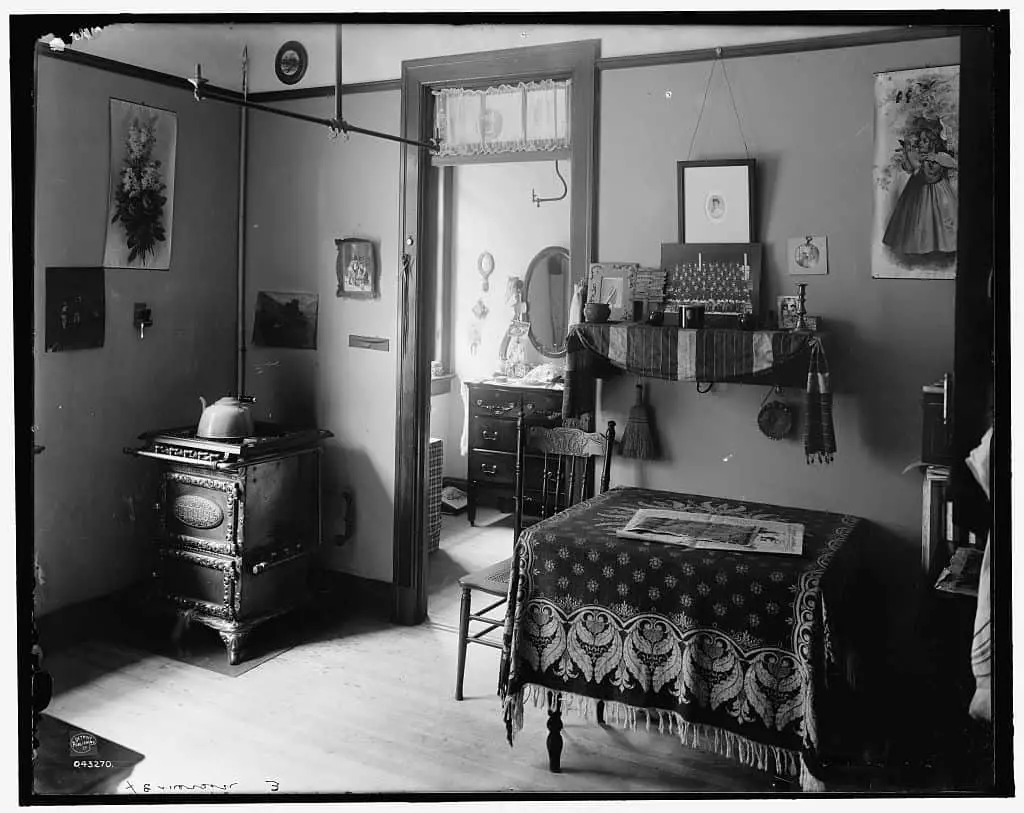

Clancy and Nora live in a ‘slum tenement’. A tenement is, in most English-speaking areas, a substandard multi-family dwelling in the urban core, usually old and occupied by the poor.

CHARACTERS

James Clancy — an Irish immigrant, Catholic, who attends church every day when he is off work after a broken hip. We’re told that he is honest, pays his debts, and — as it turns out — is intolerant of homosexuality, like many of his generation. After the backstory, the reader is not surprised.

James has not always been an elevator attendant, which is another reason for his backstory with the factory and the hip. Perhaps if he’d always been an elevator attendant he would be a more humble worker. After all, an elevator attendant is one of those jobs which basically demands invisibility. Instead, James takes it upon himself to decide who is and isn’t allowed to ride in the elevator. So although humble in some ways, James Clancy takes the high ground when it comes to morality.

Clancy’s pleasant face reflected a simple life

Nora Clancy — James’ wife. That’s pretty much all we know about her. It’s significant that James has a wife, because it signals his traditional family set up. Like Clancy, she is a ‘simple’, country person:

Nora went to market with a straw basket under her arm, like a woman going out to a kitchen garden

John Clancy — James and Nora’s son, bright and well-educated, doing well at school. It’s likely that this son of immigrants will live the American Dream of mid-century. James is so proud of his teenage son that he admires him in his sleep.

THEME

People fall in love with all kinds of different people, and there’s something about love which lets us see past our loved ones’ imperfections.

This rather didactic message comes through in the final paragraph, when Clancy has his epiphany:

He put an arm around her waist. She was in her slip, because of the heat. Her hair was held down with pins. She appeared to Clancy to be one of the glorious beauties of his day, but a stranger, he guessed, might notice the tear in her slip and that her body was bent and heavy. A picture of John hung on the wall. Clancy was struck with the strength and intelligence of his son’s face, but he guessed that a stranger might notice the boy’s glasses and his bad complexion.

Even when you disapprove, saying nothing is always an option.

And then, thinking of Nora and John and that this half blindness was all that he knew himself of mortal love, he decided not to say anything to Mr. Rowantree. They would pass in silence.

We can’t expect to understand other people who are so very different from ourselves.

The ‘Tower of Babel’ of the title is acknowledgement of that. Interestingly, it also ties transgressive lifestyles to the Bible.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

Though this is a story from an omniscient narrator, an omniscient narrator reveals things at leisure, in a manner that best suits the story. In this way, the omniscient narrator can be as ‘unreliable’ as any first person narrator. In this story, Cheever does an interesting thing by withholding the fact that James’ ‘perfect’ son has glasses and ‘a bad complexion’. Until the final paragraph, we know only that this boy is marvellous. His imperfections are withheld so that the reader’s gaining of knowledge coincides with James’s small epiphany.

STORY SPECS

Published in the New Yorker, 1951

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH “CLANCY IN THE TOWER OF BABEL”

Christmas Is a Sad Season for the Poor, also by Cheever, is about another elevator operator. Elevator operators (when they existed) had one of those jobs that let them be invisible while looking in at the lives of rich people.

As time went by, Cheever’s attitude towards homosexuality evolved. Compare this story to some of his later ones, which show a more accepting attitude:

In The Wapshot Chronicle, Cheever’s comic treatment of Coverly Wapshot’s doubts about his sexual orientation on being pursued by a male coworker only partially masks Cheever’s own apprehension and ambivalence toward his bisexuality during the late 1950s.

As Cheever became more accepting of his sexual orientation, however, it was reflected in his work. In his breakthrough novel Falconer, Cheever invests homosexuality with redemptive and transforming powers. Ezekiel Farragut, who is imprisoned for murder, acquires the ability to love only after his affair with a fellow prisoner.

In “The Leaves, the Lion-Fish, and the Bear” (1974) and Oh What A Paradise It Seems (1982), Cheever depicts bisexual experiences free of guilt or remorse within the context of marriages, signaling his acceptance of his own bisexuality.

glbtq

A New Zealand short story writer who lived around the same time as John Cheever (though was born a few years earlier) is Frank Sargeson. Sargeson was gay at a time when sodomy was illegal. Suppressed gay themes come through in some of his short stories, for example The Hole That Jack Dug.

Kai Jensen, in an exploration of “The Hole that Jack Dug,” exposes the sexual polarization common to New Zealand literature in the 1930s. He points out that the hole is indeed a parable of essential male wholeness. Few critics, however, have been willing to explore the effect of homosexuality on Frank Sargeson’s writing. An exception is Bruce King, who comments on the paradox that “Sargeson’s homosexual stories should be seen as the quintessence of New Zealandism.”

gltbq