“Cinderella” is a classic rags-to-riches tale and can be found, written straight or subverted, throughout the history of literature. It’s worth pointing out that Cinderella wasn’t truly from ‘rags’. She was related to middle class people, so was at least middle class herself. No one wants to hear about actual starvation, rickets and whatnot at bedtime. This is a middle-class-to-rags-to-aristocrat tale.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF CINDERELLA

Cinderella Is From China

Although we think of Cinderella as a quintessential European fairytale, it originates from China. If you’ve ever read the novel Chinese Cinderella, this renders the title a little moot!

The Chinese title is Ye Xian (English speakers can approximate the sound by saying ‘Ye Shen’). The plot originated in the 5th century, which makes it about 1500 years old. This is a tale from the end of the ancient world, and marks the very beginning of when stories began to be written down. (Known also as the early modern era.)

If you’d like to hear “Cinderella: Ye Xian” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Cinderella: Ye Xian” was published September 2019.

What happens in Ye Xian?

- Cinderella has a golden fish in a pond.

- She likes to go to the pond and talk to this fish, imagining it’s her dead mother.

- Her tears mingle with the water in the pond.

- She lives with a wicked stepmother who hates her, and as an act of cruelty the mother kills the beloved fish/spirit mother, cooks it and serves it up to Cinderella who is made to eat it.

- An old travelling man happens by and says, “Do not fear, the bones of the fish have great power.” He tells her to take them and use them at a time of great need.

- The rest of the story is as we know it today in the West: Cinderella ends up asking for help from the bones (rather than from a fairy godmother). The dress she wears to the ball is golden like fish scales.

It’s no real surprise to learn that Cinderella comes from China when you consider the degree to which (small) feet have traditionally been fetishised on the Chinese continent. The Chinese story does continue past Cinderella’s marriage to the handsome prince. Unlike European stories, Chinese fairytales have tended to continue past the happily ever after = marriage. In the Chinese Cinderella, there are problems in the marriage because the king is jealous of those magical fish bones. He ends up throwing the bones away so he can have his wife to himself. He is coercively controlling, in other words. Not a happy ending at all. (At least, not for women.)

How did Ye Xian make it to Europe?

The story which later became Cinderella makes its way from China across to Europe along the silk roads, together with the silks, spices and diseases. Marco Polo was famously one of the first Europeans to penetrate China. He returned to Venice in 1290. We can see the beginnings of the earliest Cinderella stories in Europe from the early 1300s.

The Neapolitan Cinderella

The tale was written down by Giambatissa Basile in Italy in the 1500s. There is now no mention of the golden slipper. Italians didn’t share the small-foot fetish with China so that part of the tale didn’t resonate and wasn’t retained. That’s not to say that footwear wasn’t associated with women’s sexuality. Basile’s heroine does wear very high heels to keep her skirts from being muddied. Basile wrote down his tales in Neapolitan, a very rare dialect. This is why his versions weren’t translated into other languages until the 19th century.

Greek Cinderella

In August 2020, Parcast’s Tales podcast also published a Greek version of Cinderella which contains cannibalism. (A young woman’s starving sisters kill their mother and then eat her.) Distraught, the woman buries her mother’s bones beneath the hearth. The bones transform into riches and set young Elle off on a thrilling journey.

German Cinderella

In August 202o, Parcast’s Tales podcast also published a German Cinderella. “When cruel tragedy befalls her closet friend, a young maiden named Two-Eyes takes her despair to a fairy, whose advice has enchanting results…”

Perrault’s Cinderella

Because of the dialect thing, Charles Perrault’s French version of Cinderella is the more famous. No one knows exactly how French storytellers were able to get their hands on the Neapolitan tale. There must have been someone who could both read Neapolitan and speak French, but that storyteller has been lost in history. (Perhaps because she was a woman.)

Perrault’s tongue-in-cheek attitude makes it clear that he himself was sophisticated enough to find the story of Cinderella a little silly, but many popular versions of the story simply disregard Perrault’s tone and focus on the cheerful optimism of the events themselves.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

To read Perrault’s version online, see Project Gutenberg.

Romanian Cinderella

In Romania there’s a version called Fairy White. The mistreated main character has only a cow. (The cow is called Fairy White). The stepmother serves the cow meat to the Cinderella character. Remembering the older Chinese tale, Romanians kept the part of the story in which the girl must cannibalise her fairy spirit.

Italian Cinderella

In Italy the story becomes eroticised. Oftentimes the violence and cruelty in Cinderella tales was more akin to horror comedy such as we see coming mainly out of America today, notably in TV series like Dexter and Santa Clarita Diet.

Grimm Brothers’ Cinderella

The Grimm Brothers’ version was transcribed from an oral retelling delivered by a very old, very poor woman. It was written down October 1810. Theirs is a far more vivid, dark and wicked tale than the version by Perrault — is this because the woman who told it was herself living in dire circumstances? The Grimm title translates to “Ash Fool” (Aschenputtel). In this version the girl has golden slippers. The Grimms’ oral source was not the French tale but came from China, bypassing Europe altogether. This shows that there are different streams and tracks for the migration of fairytales — following the various silk roads.

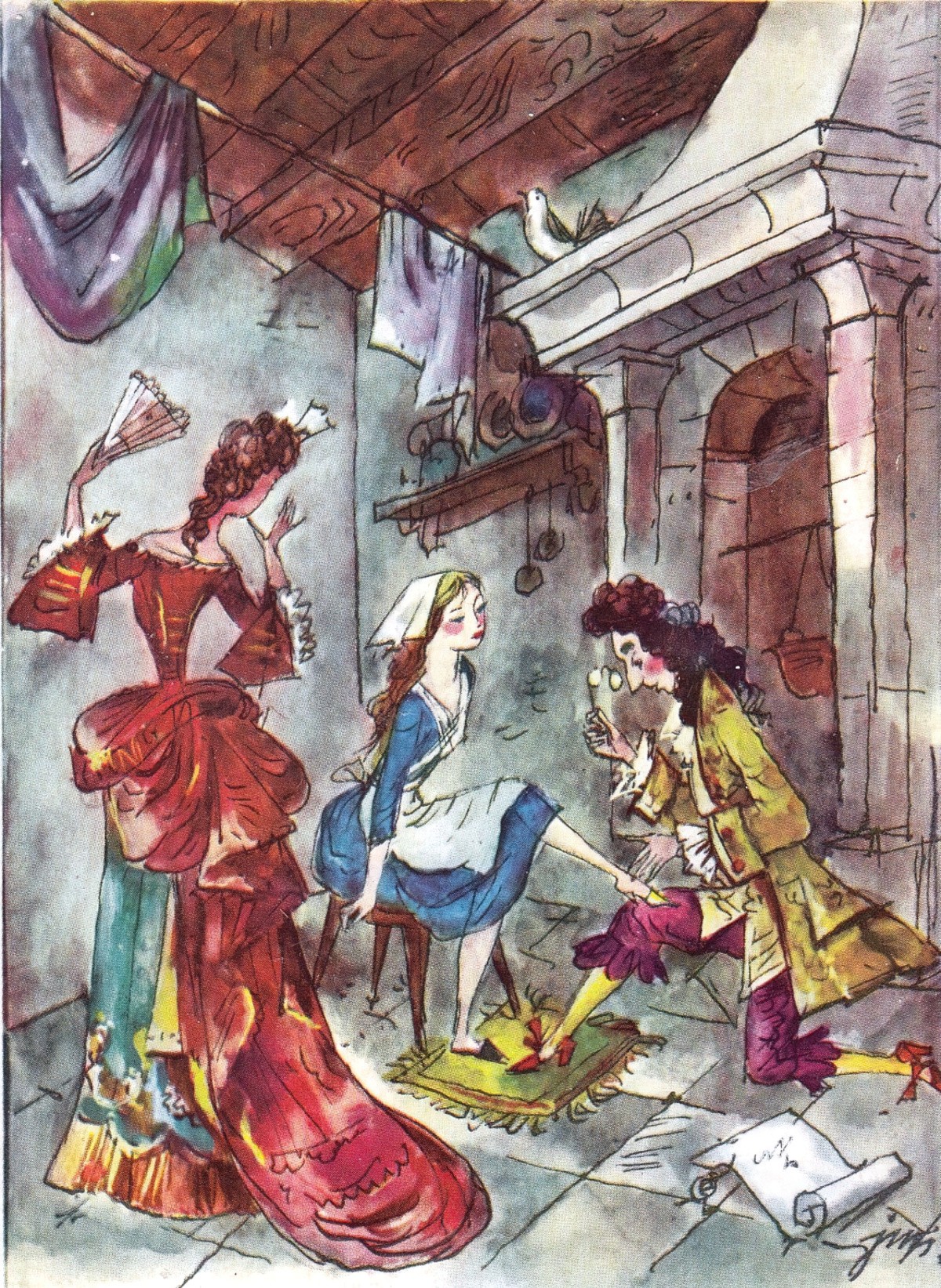

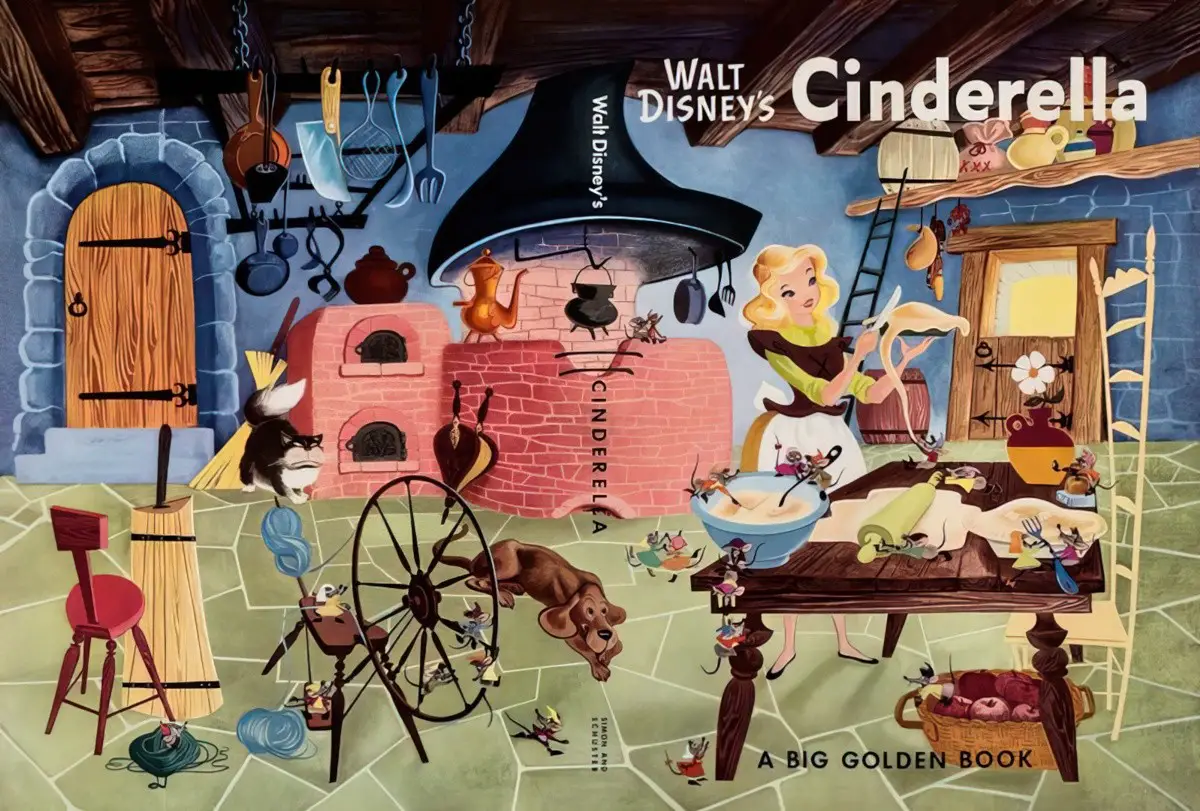

The Shoes

This tale is also sometimes known as The Little Glass Slipper or The Glass Slipper.

The glass slipper in the French retelling makes the story so memorable. Glass was always extremely rare, fragile and expensive. It really came from Venice, just as the story did. Venice was the hub of the world’s trade and also of storytelling. Stories came from places like Persia via Venice and disseminated elsewhere. The glass makes the girl perfect and rare.

Glass slippers would break easily, so anyone wearing them is clearly of a class who cannot labour. For Cinderella, who labours all day, to wear such things is the ultimate makeover.

The shoes are status symbols but also have an element of cruelty/fetishism to them. This is especially true in the Grimm version, with emphasis on how tiny the shoe is. When the prince arrives at Cinderella’s house and tries to put the step sisters’ feet into it the feet won’t fit. The mother tells the first step sister to chop off her toes. Gruesomely, she does. The other follows suit. The doves that had helped Cinderella say at this crucial point, ‘Too wit too woo, there’s blood in the shoe!” thereby ruining the step-sisters’ attempts to pass as more naturally dainty and good.

Why glass? It’s an especially resonant image. Like the milk finger in a The Electric Grandmother, we remember this detail. As a storytelling hook it works beautifully, but it was probably accidental. Glass is widely thought to have been a mistranslation of ‘fur’ from French.

See also: The Symbolism of Shoes.

Why Does The Tale Of Cinderella Survive?

This is a story of justice being served. We have a large appetite for revenge plots. We also like underdog stories. Cinderella’s journey towards being loved and having a happy home of her own tunes into a universal longing.

Cinderella paints some of the worst passions that can enter into the human breast, and of which little children should if possible be totally ignorant; such as envy, jealousy, a dislike to mothers-in-law and half-sisters, vanity, a love of dress, etc., etc. — a lady who wrote to Mrs Trimmer’s Guardian of Education in the 18th century

In the real world, underdogs don’t often win, for the simple reason that those who are powerful use their power to control things. But the magical elements in fairy tales allow events to take place that couldn’t easily happen in real life. […] the magic in fairy tales isn’t capricious. In fact, the laws of physics or logic are suspended only to get the ‘good’ characters into trouble or to help them get out of trouble, or both. Pumpkins become coaches only when underdogs like Cinderella are in enough trouble to need a suspension of reality; the magic allows her to triumph, and then it stops.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

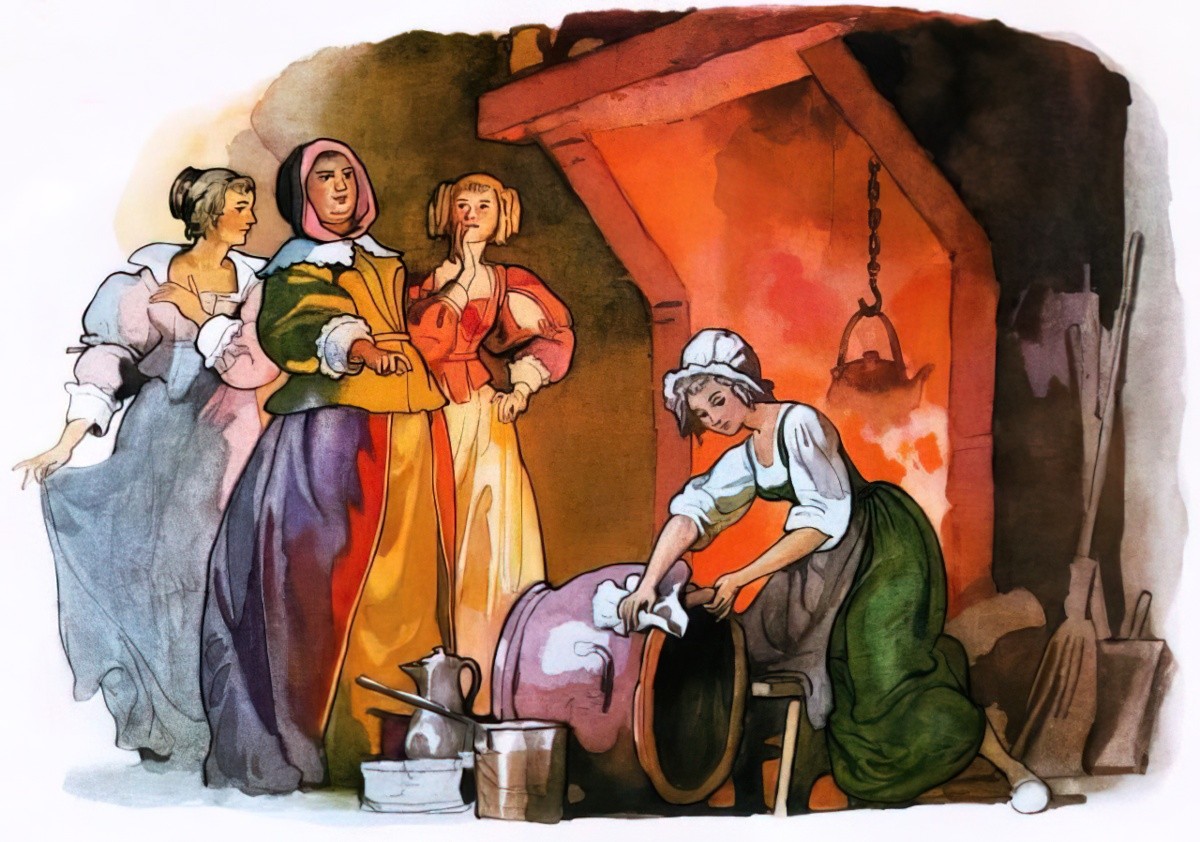

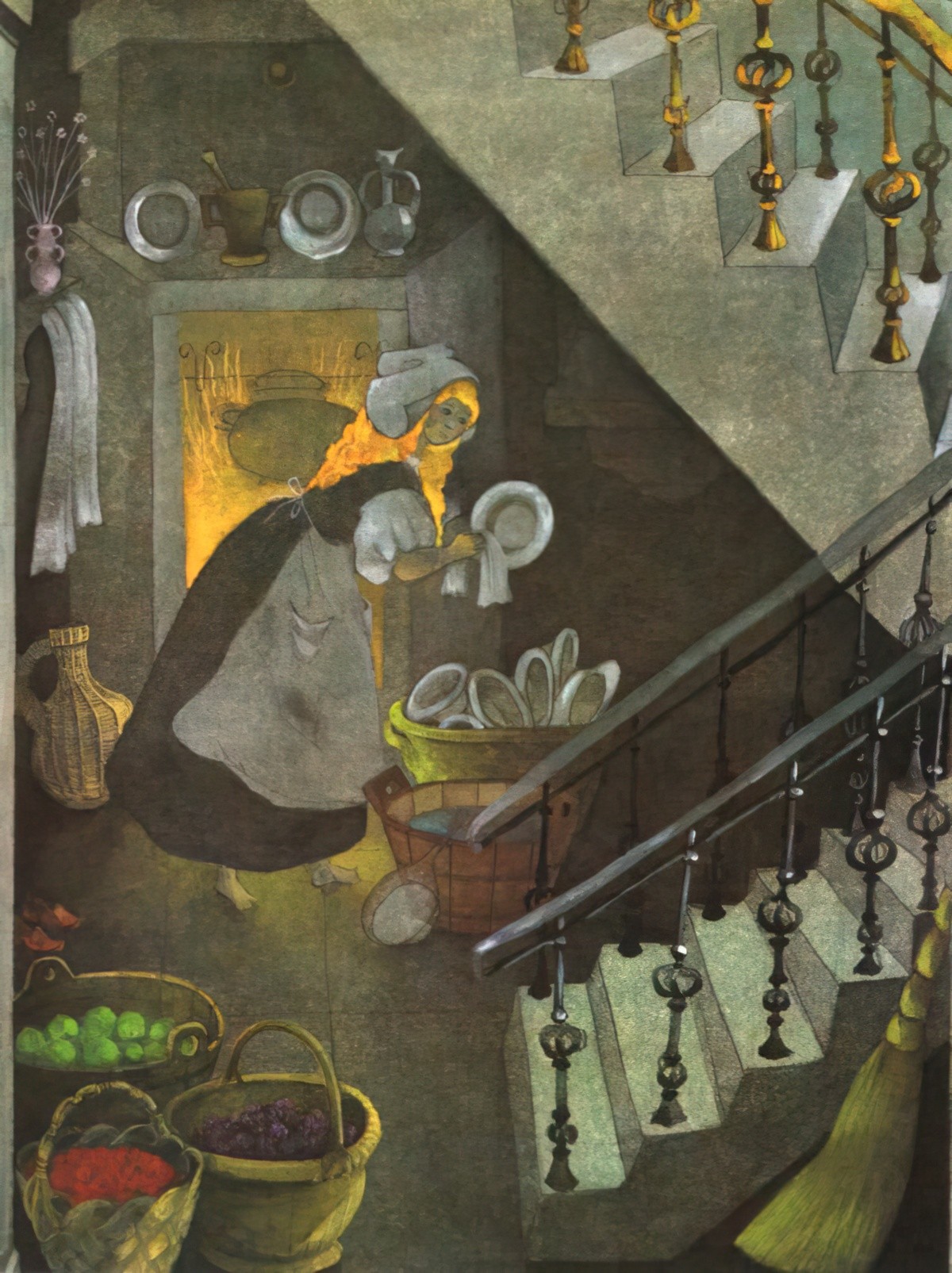

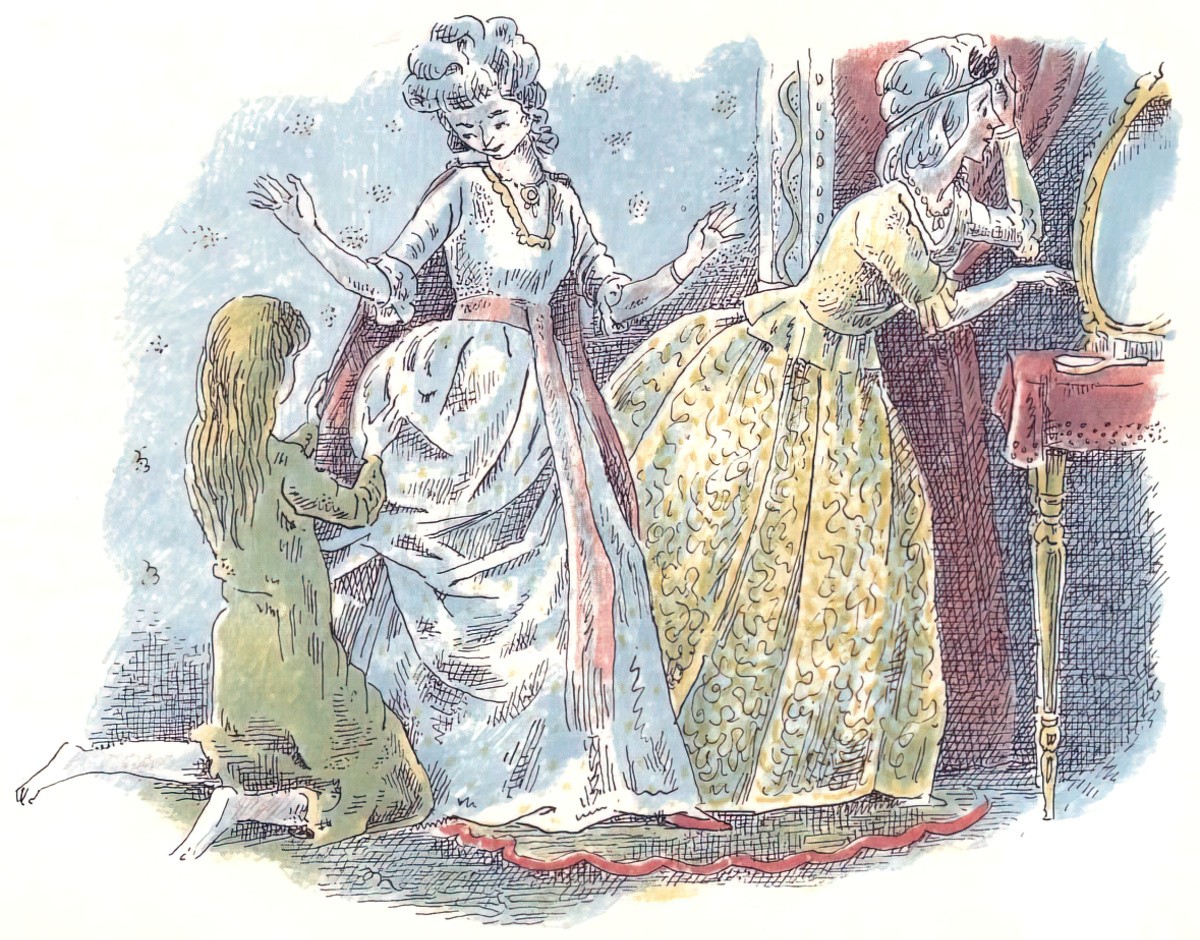

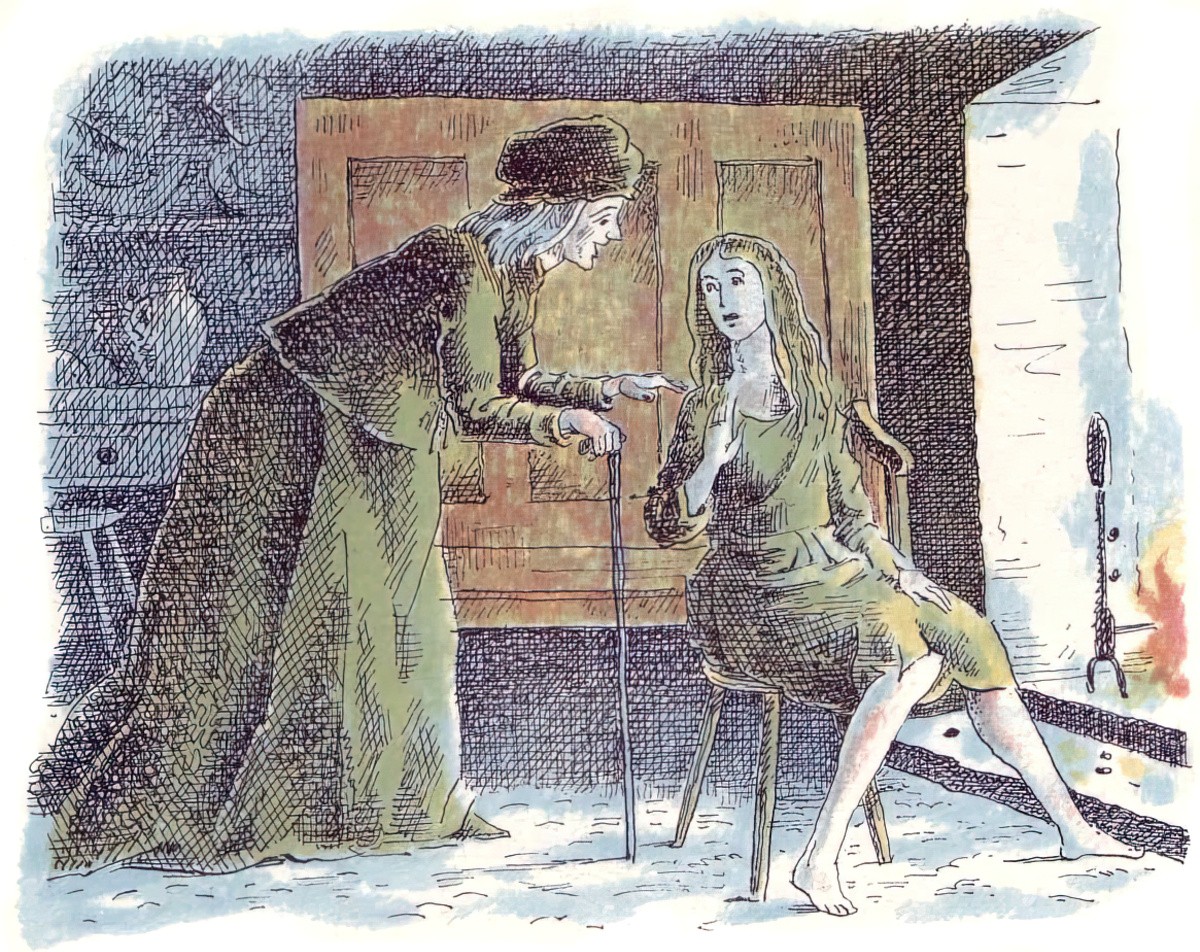

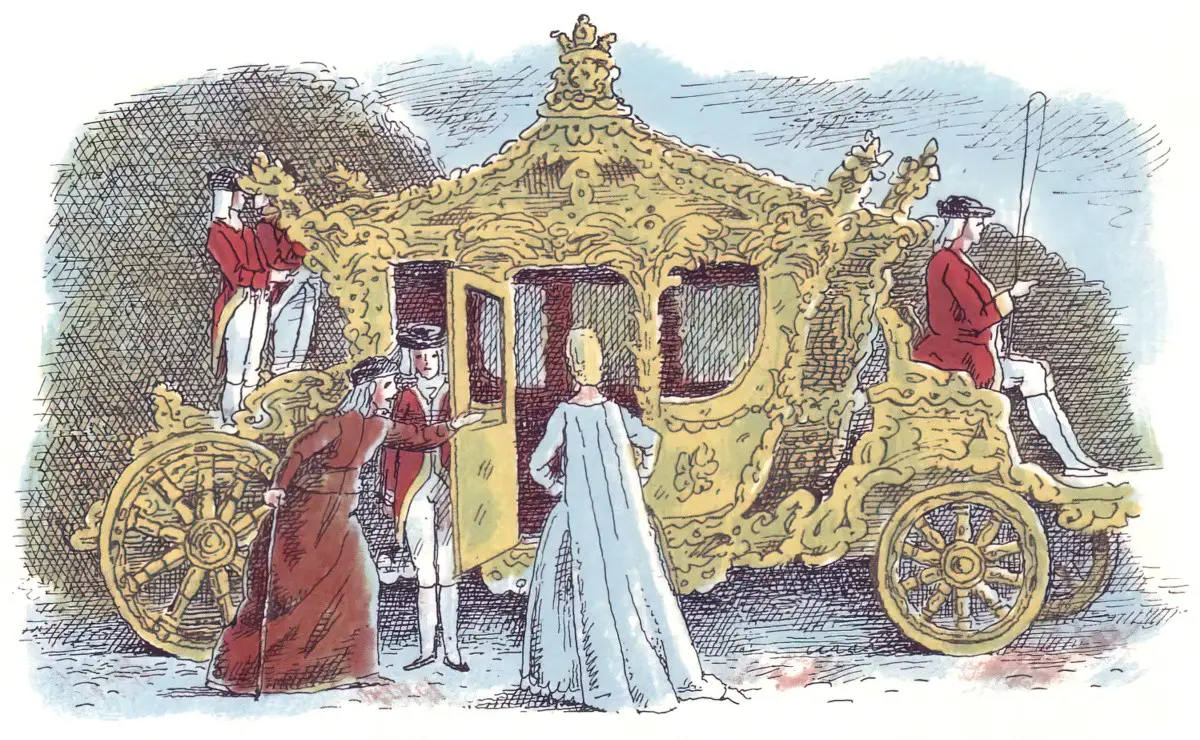

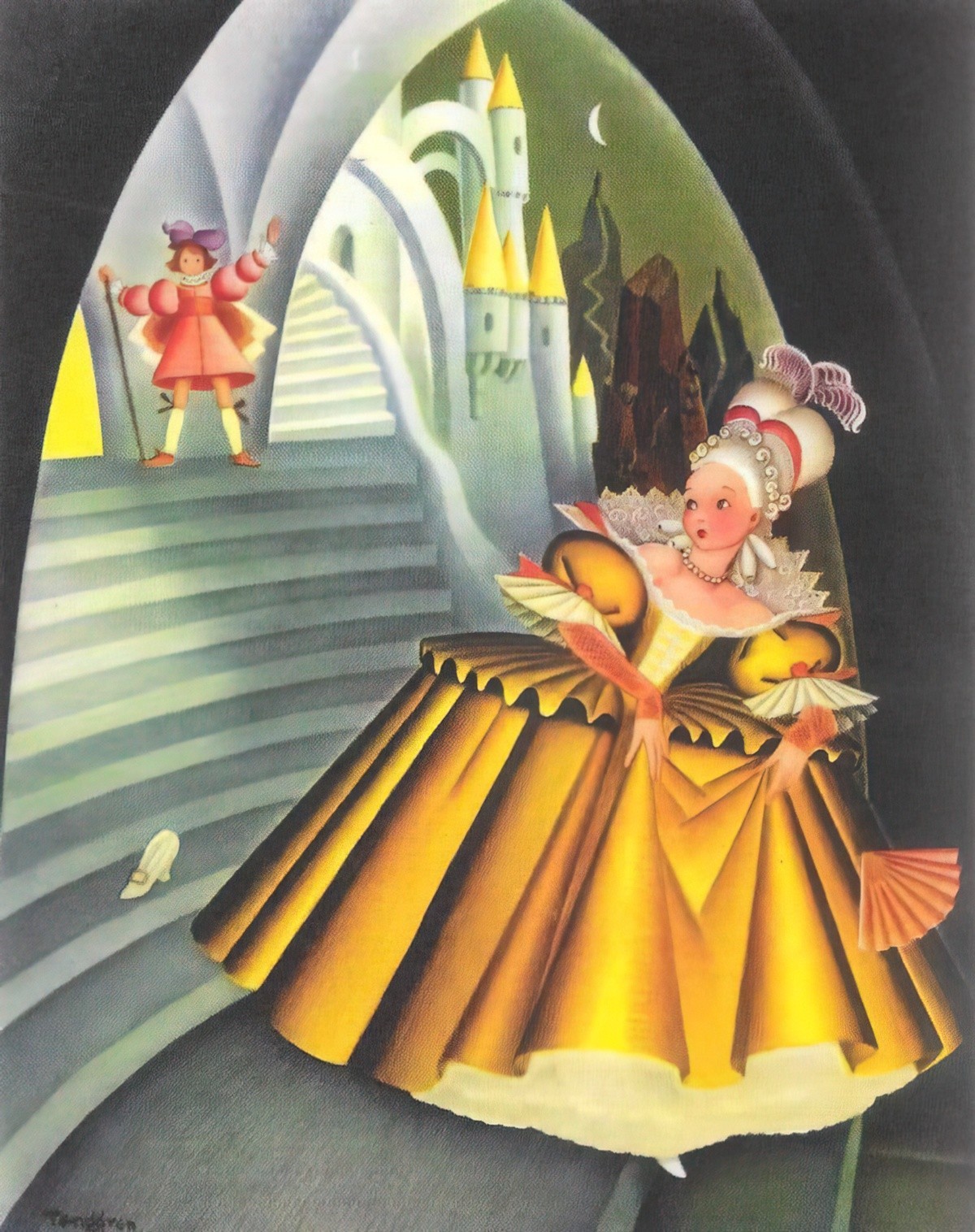

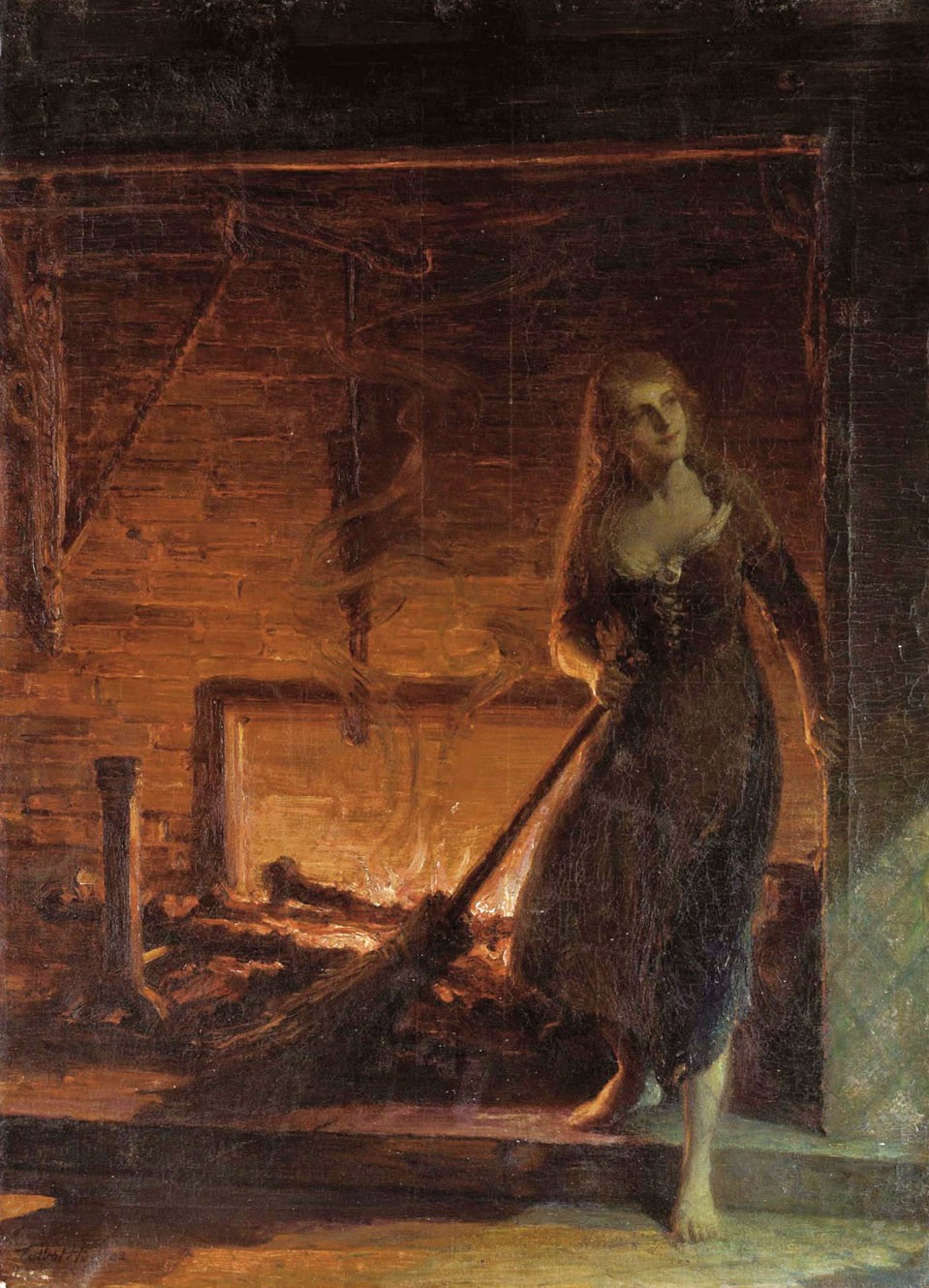

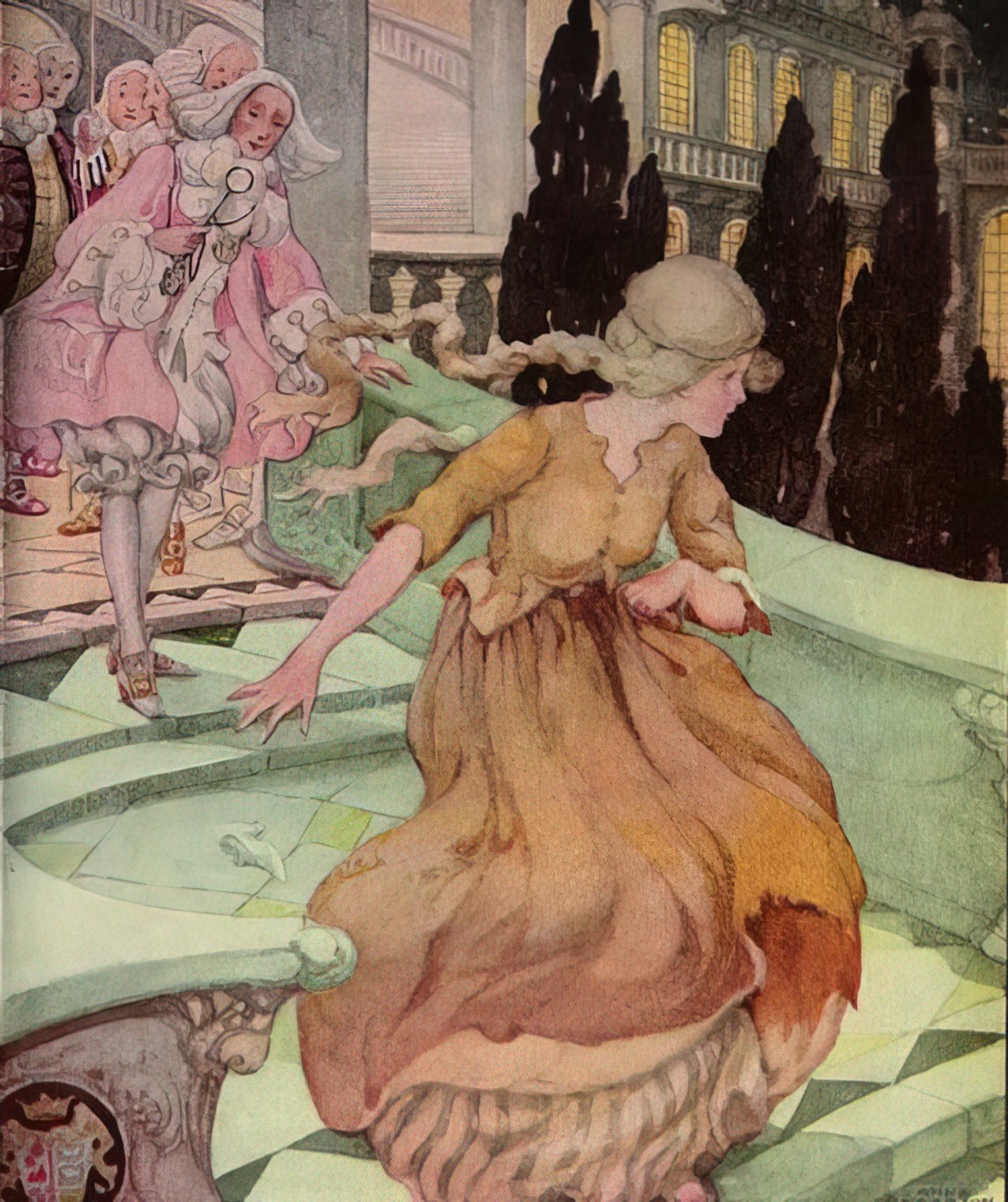

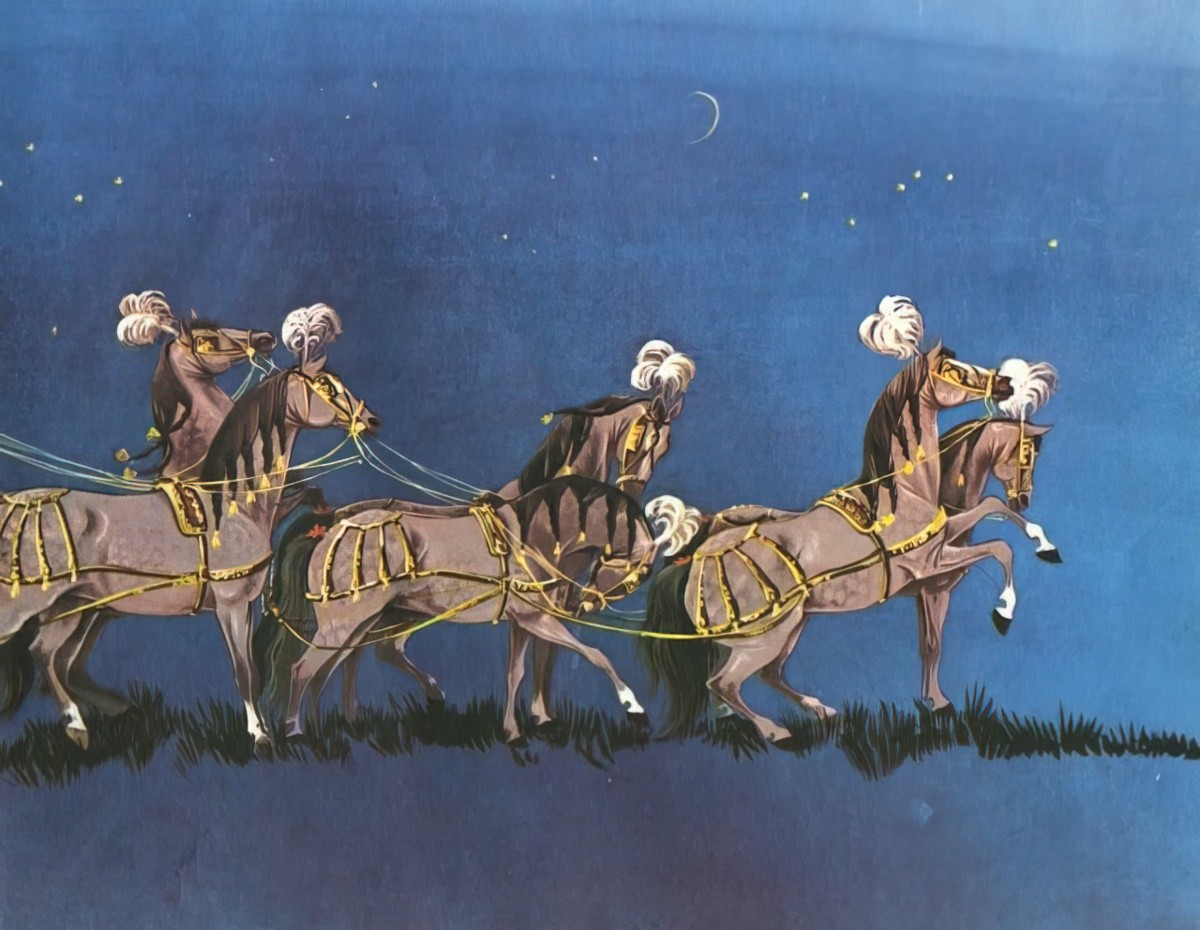

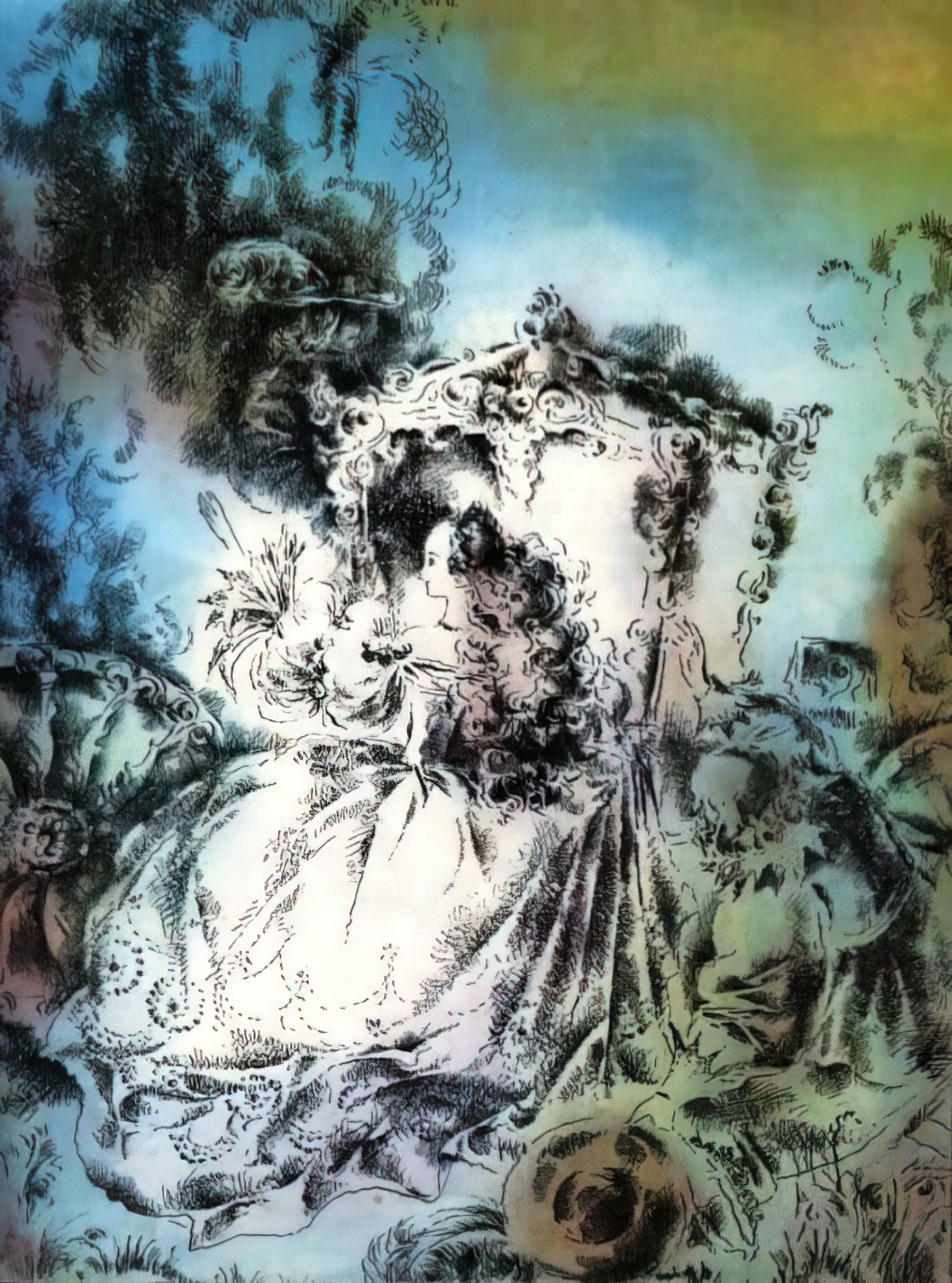

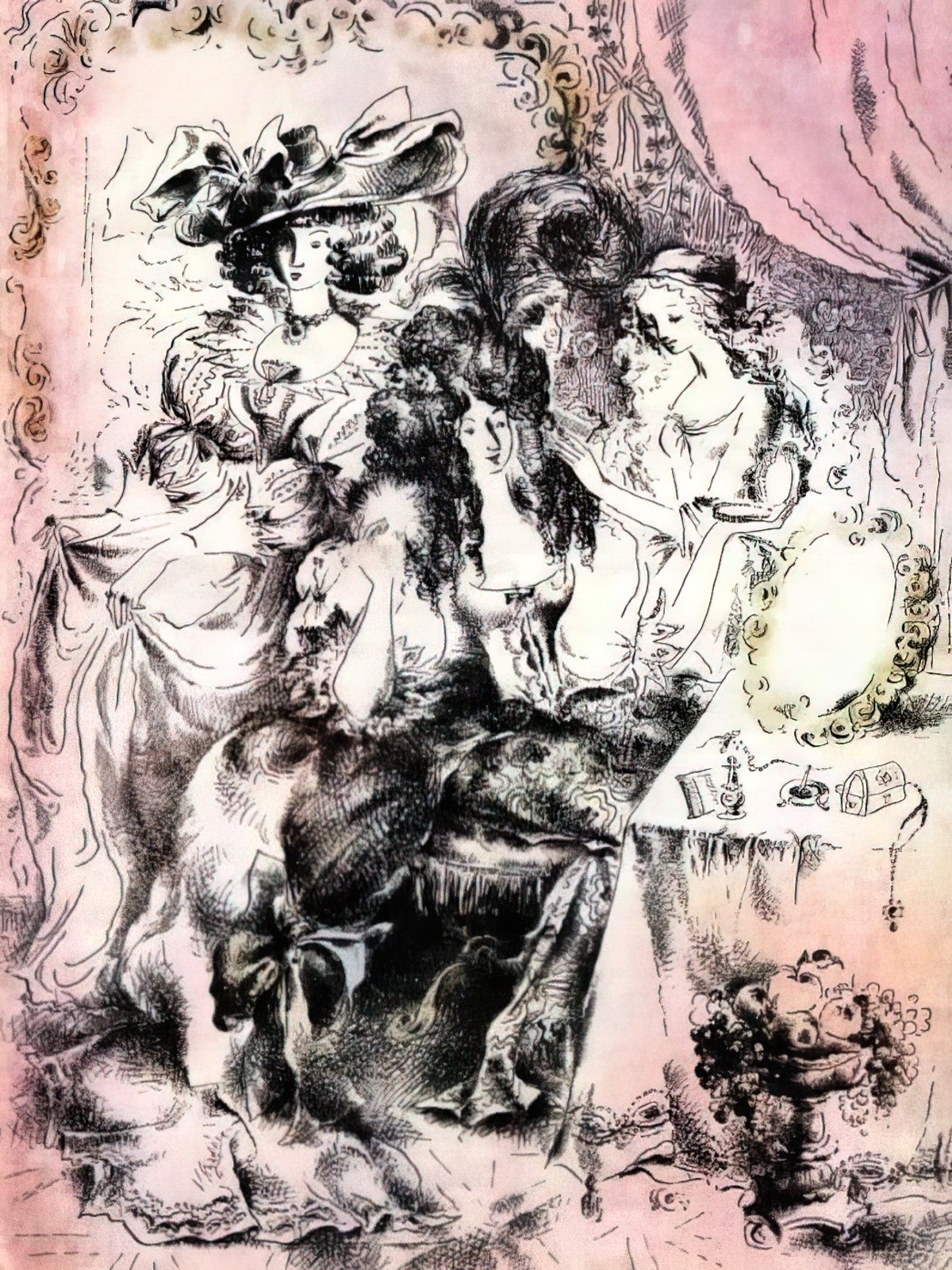

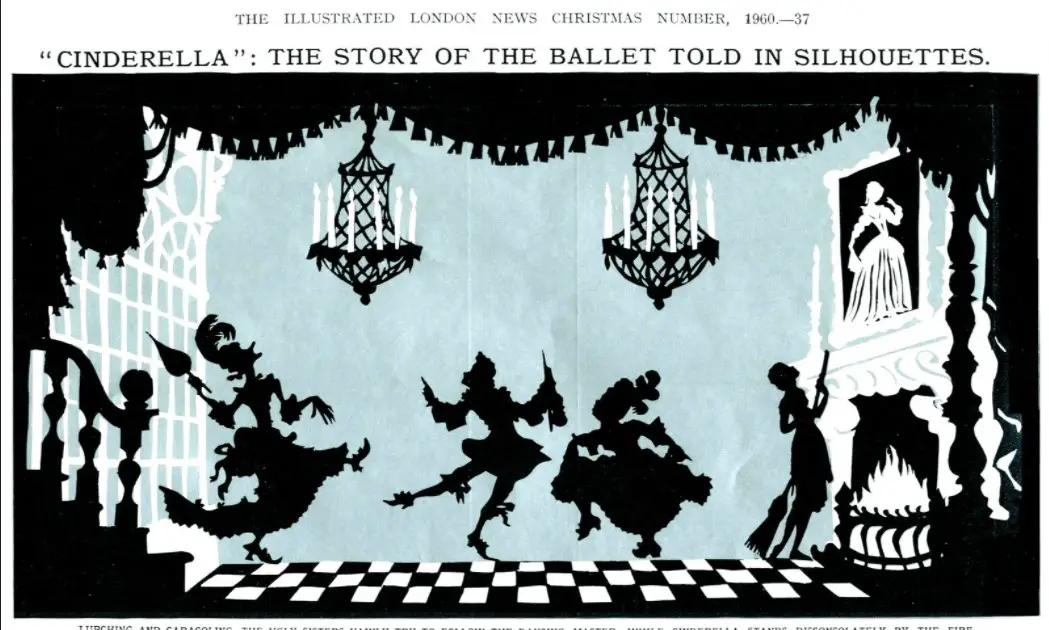

Below: illustrations by Errol le Cain (1941 – 1989) for “Cinderella, or the Glass Slipper,” an edition of Charles Perrault’s story published in 1977 by Puffin

THE ENDURING APPEAL OF CINDERELLA

There is something immensely attractive in living through a character who does obtain revenge, who is proved to have value or — like the Danish detective — is finally proved right. The attraction of wish-fulfilment, benevolent or masochistic, can’t be underestimated — what else can explain the ubiquity of Cinderella or the current global dominance of the Marvel franchise? Isn’t there a Peter Parker in most of us longing to turn into Spider-Man? Our favourite characters are the ones who, at some silent level, embody what we all want for ourselves: the good, the bad and the ugly too.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

THE CHARACTERISATION OF CINDERELLA

The passivity and stupidity of fairytale heroes and heroines may be a wise ability to accept that which transcends the limitations of ordinary reason and logic. Cinderella is passive and stupid enough—or wise enough?—to accept the help of her fairy godmother without question. Following this reading, it would appear that European fairy tales express the paradoxes central to the Christian culture they emerged from; the fool in his folly is wise, and the meek do inherit the earth. This, indeed, is the conclusion of J.R.R. Tolkien, who understands the ‘joy’ of the happy ending in fairy tales, what he called the ‘eucatastrophe’, as permitting readers a taste of the ultimate joy of resurrection that Christians hope for.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

Is Cinderella really that good?

We might speculate that, if there were a sequel to ‘Cinderella’ that fulfilled the expectations of fairy tales, Cinderella herself would probably have to be the villain. Her marriage has given her the sort of status and power audiences knowledgeable about the world of the fairy tale expect to be a source of evil. Her marriage has given her the sort of status and power audiences knowledgeable about the world of the fairy tale expect to be a source of evil.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

Cinderella and her fairy godmother can also be coded as models for modern consumerism, exhibiting ideals which are rapidly losing tract as we head further into a climate crisis:

Now that Cinderella is dressed for the part, she can be the part. The recent film version of Cinderella, Ever After, made this even clearer by showing that court dress was actually a kind of disguise. And this modern Cinders isn’t ‘really an upstart; she deserves to get on because she is kind and good. The fairy godmother is a means of obtaining all this largesse without evil consumption; indeed, from Perrault onwards, Cinderella’s prudent housewifery is routinely contrasted with the doomed and fashion-conscious consumption of her stepmother and stepsisters. If the fairy godmother is simply replaced with an American Express Platinum Card, the fear that anyone might simply buy status is aroused. The story gets around this by delegating the bills to someone for whom they have no meaning.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A History of Fairies and Fairy Stories

The Screenprism video below depicts Cinderella as a trauma victim, focusing on the Disney version.

CINDERELLA AS UR-STORY

Some stories are overt retellings and re-visionings of the Cinderella fairy-tale; these are easy to spot because they often have Cinderella in their title or in their marketing blurb. There are many other stories which make use not of the Cinderella plot per so, but of the typical ‘Cinderella story structure’. Many other stories use a basic Cinderella story structure. They’re also known as ‘rags-to-riches’ stories. A few examples:

- Pretty Woman — one of the only rom-coms which has gained wide popularity and attention outside rom-com circles

- Arthur

- Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier is a blend of the Bluebeard/Cinderella traditional tales

- Suspicion

- Charlie And The Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl — A genuinely poor boy finds wealth after proving his goodness, not with the aristocratic class but with the wealthy industrial class, of which Roald Dahl was himself a member.

- Maid In Manhattan – has a fairytale title when you think about it

- Slumdog Millionaire – a film set in India about a destitute man who wins a lot of money in a game show

- Notting Hill — the Cinderella character is actually a man with floppy hair, or is it the Julia Roberts character, in a sort of inverse riches-to-rags settlement?

- Piper by Emma Chichester Clark is a rags-to-riches tale starring a mistreated dog

- Jane Eyre — “The most classic nineteenth-century Cinderella story is probably Jane Eyre. The beginning of the book especially conforms to the pattern: Jane’s aunt, Mrs. Reed, and her three cousins are as awful as any stepmother and stepsisters. The theme is repeated when Jane goes away to school and is persecuted by teachers and students alike. The fairy godmother who helps her is also a teacher, Miss Temple, and her further adventures have fairytale parallels.” (Alison Lurie)

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen also has a mad mother and some ditzy sisters. She is also disadvantaged, and finds her way out by finding Mr Darcy. So this makes use of the same basic template as Cinderella.

- Boston Adventure by Jean Stafford — Alison Lurie marks this book the last true Cinderella story by a first rate modern writer. Published in 1944, this basically coincides with the end of the war. Interestingly, we haven’t seen a straight-up Western since the end of the second world war, either. The second world war marked a new era of genre subversions. Everything everyone thought they knew about the world must have been marked out as wrong. Stafford’s story contains an impressive fairy godmother character who turns out to be a kind of witch. Boston Adventure is a fairy tale because the heroine gets her wish. However, Sonia never gets to marry the prince. As you can see, this is the beginning of the subversion.

THE CINDERELLA STORY STRUCTURE

Cinderella has a typical initial situation in a fairy tale: the hero loses his/her identity and becomes a ‘nobody’. The motif is found in fairy tales all over the world, and also in the Bible story of Moses. The Cinderella-structure is a linear story in which the boy becomes a man/girl becomes a woman. There’s no going back to where the hero started from.

- The hero is subject to a series of trials: The first trial is loss of home. Maybe the hero is sold or the parents die or the family doesn’t have enough money to survive. The hero may come back, but the home, as it was, is lost forever.

- The hero often finds affinity with animals or similar.

- The trials that follow are as a result of losing the home — sleeping rough, being tired/cold and otherwise physically uncomfortable. Eating basic food and not enough of it. The hero is thrown into utmost misery but each time ascends. (This is also the basic pattern of an initiation rite.)

- Each temporary ascension anticipates the hero’s final reward, but each descent must remind the hero that they’re not yet a fully accepted member of the community. Each descent is a symbolic death. Each recovery is a resurrection.

- The hero will probably be left alone, and feels lonely.

- But help comes exactly when it is needed. In Cinderella it’s the fairy godmother. It might equally be a rich/kind benefactor or finding something magical within the setting.

- The characters in a fairy tale are fairy tale archetypes. (Heroes, Helpers, Villains, Prizes, Antogonists/Failures)

- There is often a false happy ending — at this point the plot won’t have been satisfactorily resolved.

- A dramatic but quick complication will follow.

- The hero will be re-established in his/her ‘true identity’ — in fairy tales this is with the help of some sort of token (a lock of hair, a ring, a dragon’s tongue… a shoe that fits or pretty much anything)

- The true happy ending comes about when everyone knows how wonderful and special the hero really is (from circumstance of birth) and they are returned to their privileged position in society. ‘And they all lived happily ever after’.

GOODY TWO-SHOES

The plot of Goody Two-Shoes seems to quite closely follow the bullet-points above. Though most of us know the term ‘Goody Two-Shoes’, the plot of the story is less well-known. As outlined by John Rowe Townsend in Written For Children:

- Goody Two-Shoes’ parents are turned off their farm by a grasping landlord and soon afterward die: her father from a fever untreated by the vital powder and her mother from a broken heart.

- She and her brother Tommy wander the hedgerows living on berries. Tommy goes to sea; Goody Two-Shoes (so nicknamed because of her delight on becoming the owner of a pair of shoes) manages to learn the alphabet from children who go to school, then sets up as a tutor, and eventually becomes principal of a dame-school.

- There is a good deal about her work as a teacher and her efforts to stop cruelty to animals.

- Eventually she marries a squire, and at the wedding a mysterious gentleman turns up. “This Gentleman, so richly dressed and bedizened with Lace, was that identical little Boy whom you before saw in the Sailor’s Habit.” In other words it is brother Tommy, who has of course made his fortune at sea.

- And so Goody Two-Shoes, now rich, becomes a benefactor to the poor, helps those who have oppressed her, and at last dies, universally mourned.

A NOTE ON LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY

Little Lord Fauntleroy has been called “the best version of the Cinderella story in the modern idiom that exists.” (Laski.) It has also been discussed in the general terms of a fairy tale and as a Cinderella tale in particular. Much as the idea of the three sons, the first tow being good-for-nothing, and the youngest the most handsome, kind and worthy, is a fairy-tale pattern, Little Lord Fauntleroy […] is definitely not a Cinderella plot. Cedric has in fact not done anything to deserve his sudden happiness; he has not gone through any trials nor endured any hardships, he has not had any quest nor gained any experience. His tremendous goodness alone does not qualify him to be a Cinderella. The Cinderella (or Ugly Duckling) plot moves from ashes to diamonds, from nothing to everything, from humiliation to highest reward; Cedric at most exchanges spiritual wealth for material.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

CINDERELLA SUBVERSIONS

When I began to look for a modern Cinderella, I had more difficulty. The story is still being written, but not for an intellectual audience. The women’s magazines and the contemporary gothic novel are full of it, and (if we are to judge from the newspapers) it occurs frequently in real life. But serious women writers apparently no longer believe in upwardly mobile marriage as a happy ending. Even Edith Wharton, seventy or eighty years ago, didn’t believe in it: The House of Mirth is a devastating account of a Cinderella who doesn’t catch the prince and finally can’t even marry a toad; and in The Custom of the Country the prince goes off with the ugly sister.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The power of subversive children’s literature, writing in the 1990s

FEMINIST RE-VISIONINGS

He’s not nearly as attractive as he seemed the other night. / So I think I’ll just pretend that this glass slipper feels too tight.

by Judith Viorst, who also wrote Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day

The Paper Bag Princess By Robert Munsch, Illustrated by Michael Martchenko

In a discussion of feminist retellings of popular fairytales, Nodelman and Reimer point out that although adults like these tales for modern children, unless children have been exposed to the earlier tales as written down by Grimm and Perrault, feminist retellings fall flat:

Such stories often strike adult readers as both enjoyable and useful. They are funny, and they present worthwhile role models. What adults often forget to consider is the degree to which their pleasure in these stories depends on their knowledge of all those other stories in which the princes rescue the princesses. Without the outmoded, sexist schema of those stories to compare it with, The Paperbag Princess loses much of its humor and almost all of its point. If adults assume that such stories are good for children, then they must believe one of the following:

- Children should first be taught the outmoded, traditional role models so that they can then be untaught them.

- Children already know these role models:

- It is natural for children to assume that women are weak and men strong; or

- They learn the notion so early in life that it’s firmly established by the time they’re old enough to hear simple stories like The Paperbag Princess.

In fact, this last possibility seems the most likely one. In interviews with children about The Paperbag Princess, Bronwyn Davies discovered that they interpreted—we adults might say, misinterpreted—the story to make it fit into their already established ideas about appropriate behaviour for males and females. When Ronald thanks Elizabeth for rescuing him from the dragon by telling her she looks awful and that she should go away and come back only when she looks more like a princess, these children were convinced that he’s only doing what needs to be done. Elizabeth needs to be warned about the danger of behaving in such an unfeminine manner because her actions are a threat both to her and to Ronald. According to Davies, these children understood Ronald’s cruel words as what she calls ‘category maintenance work’: behaviour ‘aimed at maintaining the category as a meaningful category in the face of individual deviation which is threatening the category’. In this case, the category is gender roles, and the children Davies interviewed knew and believed traditional ideas about them thoroughly enough to reinvent the meaning of Munsch’s story. Not surprisingly, they had serious trouble making sense of Elizabeth’s apparent happiness at the end of it. Davies concludes, ‘Certainly the idea that children learn through stories what the world is about or that they use the characters in stories as ‘role models’ is not only too simplistic but it entirely misses the interactive dimension between the real and the imaginary’.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature

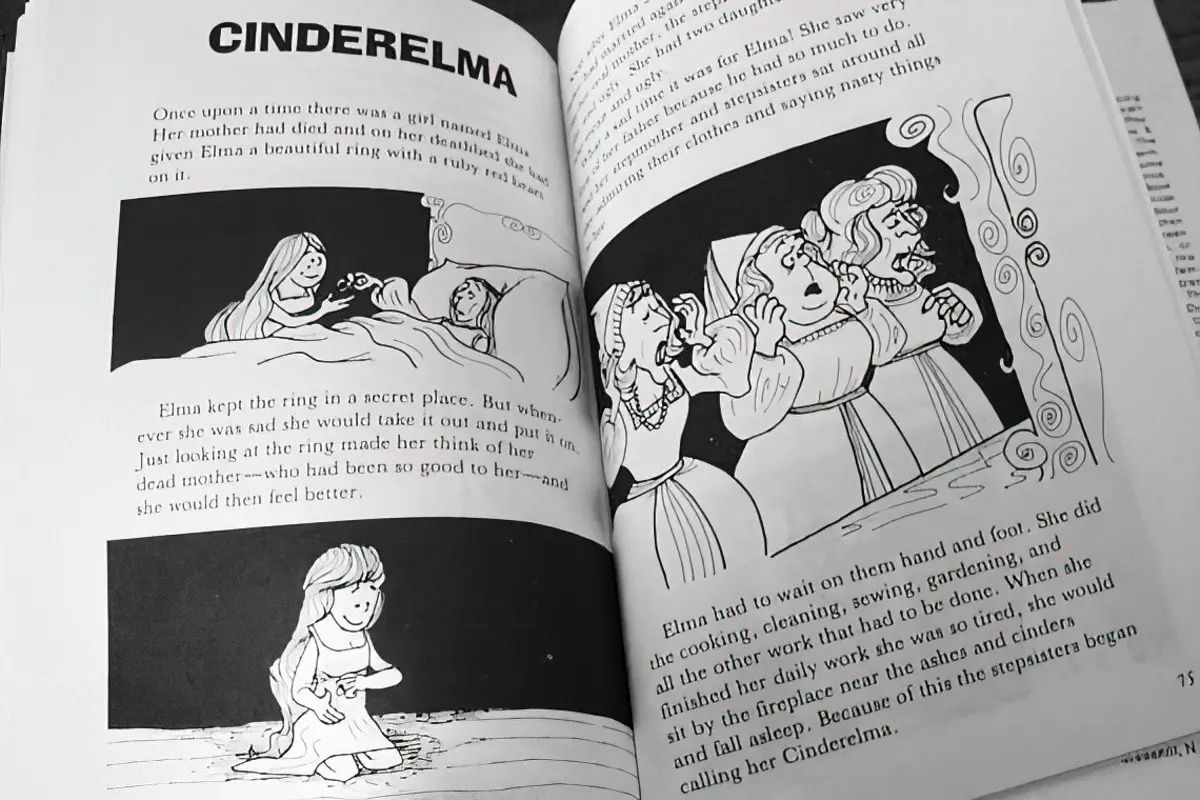

CINDERELMA AND ELLA ENCHANTED

In any case, all stories reflect the ideologies of their tellers. If those tellers aren’t yet as liberated as we might wish they were, then the stories they tell, despite their good intentions, won’t be any more liberated. In ‘Cinderelma’ from Dr. Gardner’s Fairy Tales for Today’s Children by Richard A. Gardner, MD, and in Ella Enchanted by Gail Carson Levine, a liberated woman still achieves happiness by marrying the man of her dreams. Indeed, marriage is the happy ending.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature

Cinderella and the Hot Air Balloon by Ann Jungman and Russell Ayto

In this 2004 retelling, Cinderella is a ‘tomboy’ (my quote marks mean I really don’t like implied established gender roles) who insists that Prince Charming changes his name to something sensible like Bill. Instead of the whole slipper saga, they both take off in a hot air balloon. In other words, you still get the Happy Ever After. I don’t think this story is sufficiently different to warrant a retelling. (I thought the same after watching Tim Burton’s Alice.) There are so many fairytales out there — even if we just stick to those collected by the Grimm Brothers — that I doubt it’s possible to tire of them before the Fairytale Phase has been outgrown. If we’re going to rewrite any, I think that one, they need to be significantly different and two, they need to have an original spin (e.g. a modern setting which affects the characterisation).

Cinderfella

Jerry Lewis starred in a movie called Cinderfella, about a male character in the same situation. He needs to be rescued.

Cinderella Dressed In Yella

See also: Cinderella Dressed In Yella by Ian Turner (Australian — Monash University). Turner taught Australian History and talked about football all the time. This second year lecture was so popular that people needed to be booked in advance. He gave a sexual interpretation to the egg shaped ball being passed around a field, passed around pies etc. He also talked about the tradition of folklore.

OTHER CINDERELLA RELATED LINKS

- Cinderella Fairy Tales: Online Resources

- For a list of picture books which are variations on the classic Cinderella tale, see this post from Teach With Picture Books.

- Kevin Fallon points out at The Daily Beast that Orange Is The New Black is full of Cinderella stories

Reverse Cinderella. Just a bunch of rats and birds absolutely ruining a prince’s life until he is the perfect match for a local servant girl.

[cf. Shrek!]

@pairofclaws on Twitter 2022