“Bluebeard” is a classic fairytale — the O.G. tale of domestic violence. Any story in which a fearsome husband murders his young wife is probably a “Bluebeard” descendent. The husband in this tale is monstrous, and related to the archetype of the ogre.

If you’d like to listen to the tale, I recommend the (free) podcast version offered by Parcast.

Or listen to Bluebeard and other short ghost and horror stories at Librivox recordings:

Palestinian Bluebeard

If you’d like to hear a Palestinian tale similar to “Bluebeard”, check out “Zerendack and Abu Freywar”, retold by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Country Where Death Is Not” was published July 2020.

The Palestinian story was first recorded in 1904.

I never encountered the story of “Bluebeard” growing up, as it was left out of my childhood fairytale anthologies.

There are versions of Bluebeard all over the world:

- Catalonia

- Iceland

- Greece

- Puerto Rico

- West Indies

There is always a forbidden chamber with hidden contents. This is a take on the ancient Pandora story, in which a young woman looks where she should not. (See also: Eve, Lot’s wife and Psyche.) The contents of this forbidden chamber differ from region to region:

- Dead former wives

- Bodies in which the gender is not specified

- Body parts

- A prince

- The portal to hell

The ending also differs: Various characters help the young woman to escape. Occasionally she escapes on her own.

French folklorist Charles Perrault included a “Bluebeard” story in his well-known Stories. Folklorists don’t know where he got his inspiration from, exactly, but there are theories, based on the fact that Perrault was a hagiographer as well as a fairytale enthusiast:

- Ballads of maiden kidnappers which went around Europe in the 1500s

- The “Mr Fox” tale from England

- the St Gilda legend about the 6th C saint who revived Tryphine, who had been beheaded by her husband (Comorre or Cunmar) when he learned she was pregnant.

- The historical figure Gilles de Rais (1404-40). This psychopath sexually abused and murdered more than 140 children. He is also remembered as a comrade of Joan of Arc.

As a mental mouthwash, I suggest you read Angela Carter’s feminist version of “Bluebeard” after reading this much earlier one by the misogynist Perrault. Carter’s story is called The Bloody Chamber (1979). Bluebeard re-visionings are deemed feminist when the storyteller removes blame from the young woman (for disobeying her husband) and places blame with the violent murderer himself. Another feminist re-visioning is Bluebeard’s Egg by Margaret Atwood (1983). In some Bluebeard-type stories, the bloodstain is found on an egg rather than on a key.

The French title of Perrault’s retelling is La Barbe bleue. In the 1500s, ‘barbe bleu’ actually referred to a man with a raven black beard. Men with such beards were thought to be seducer types.

DEATH BY ENGULFMENT STORIES

Disturbing as it is, the Bluebeard story has an influence on many modern tales, so is worth a read for that reason. Cruel as it is towards women, I argue that is a story for women.

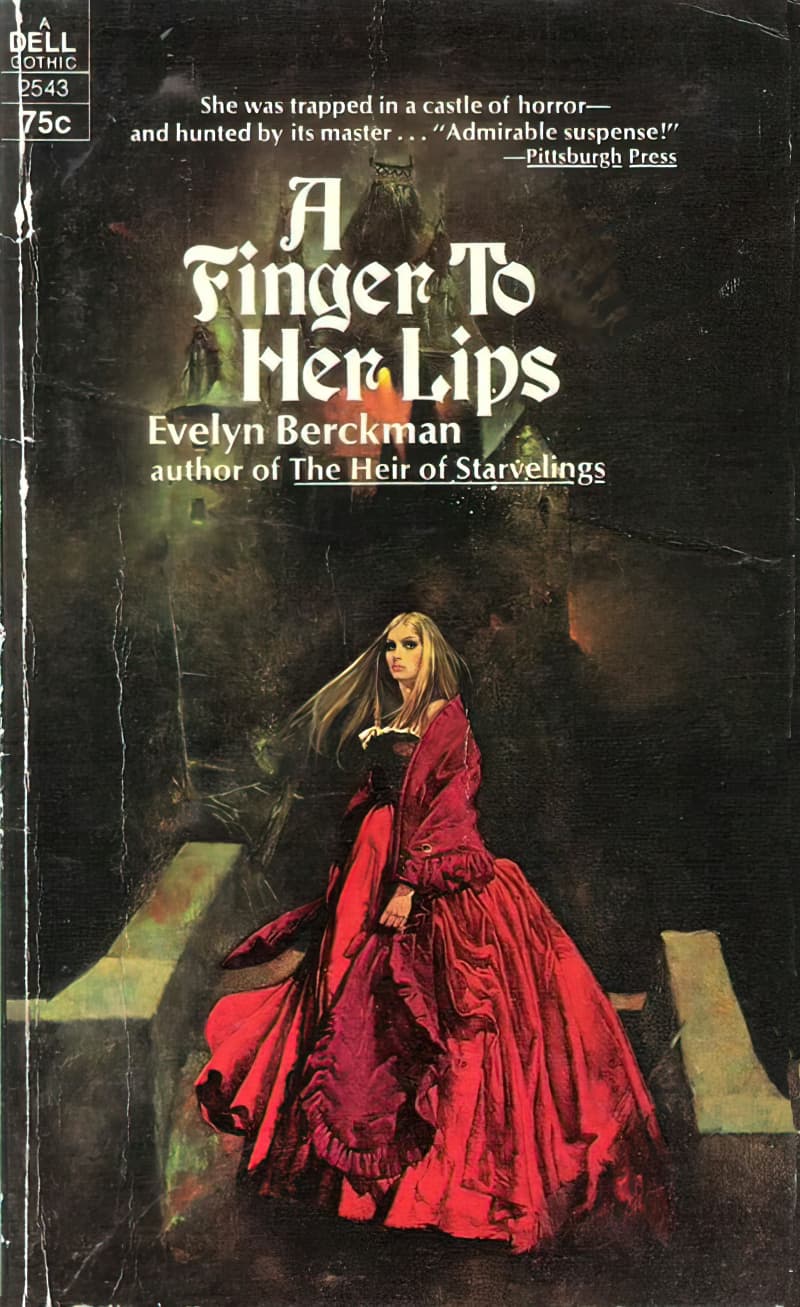

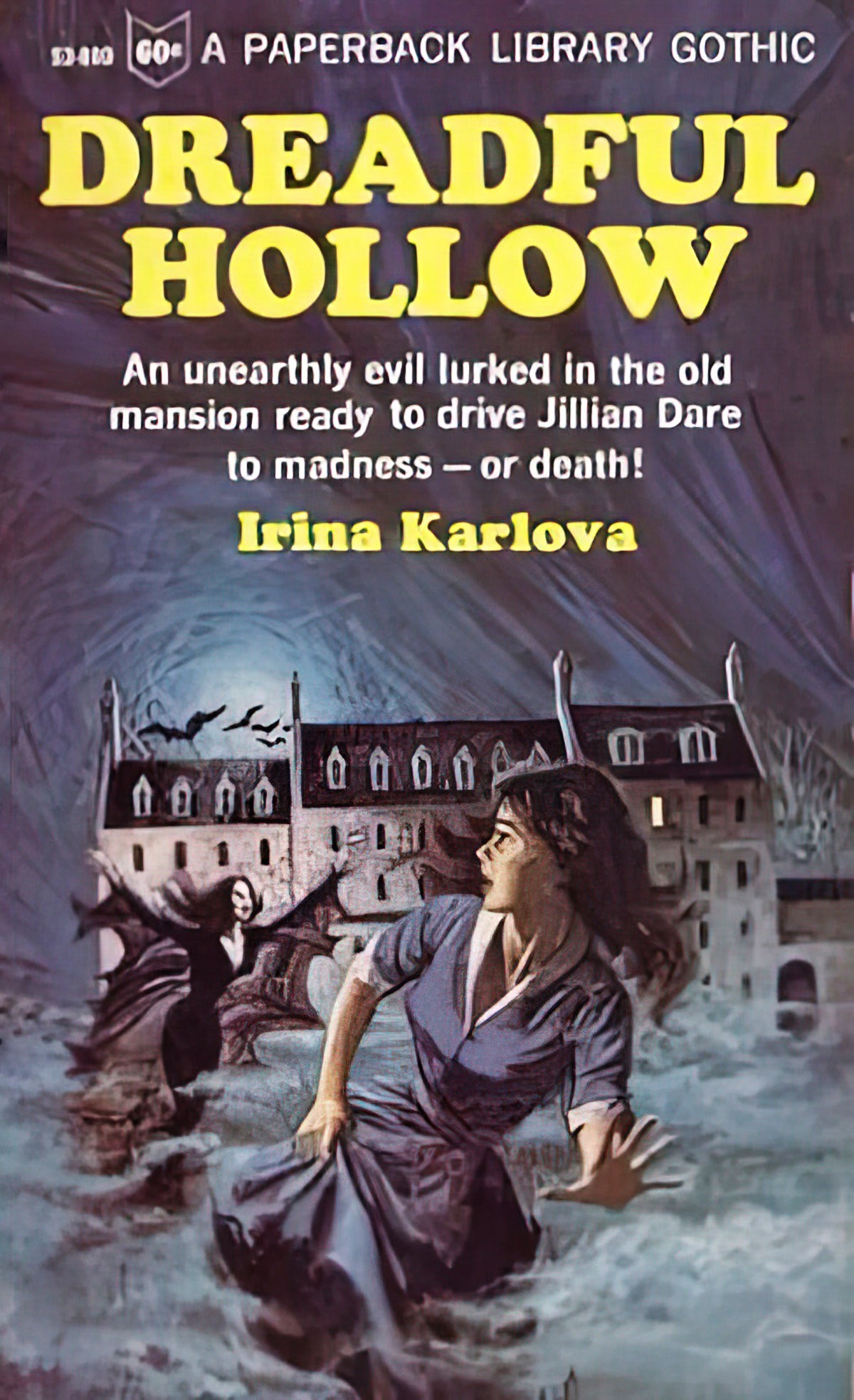

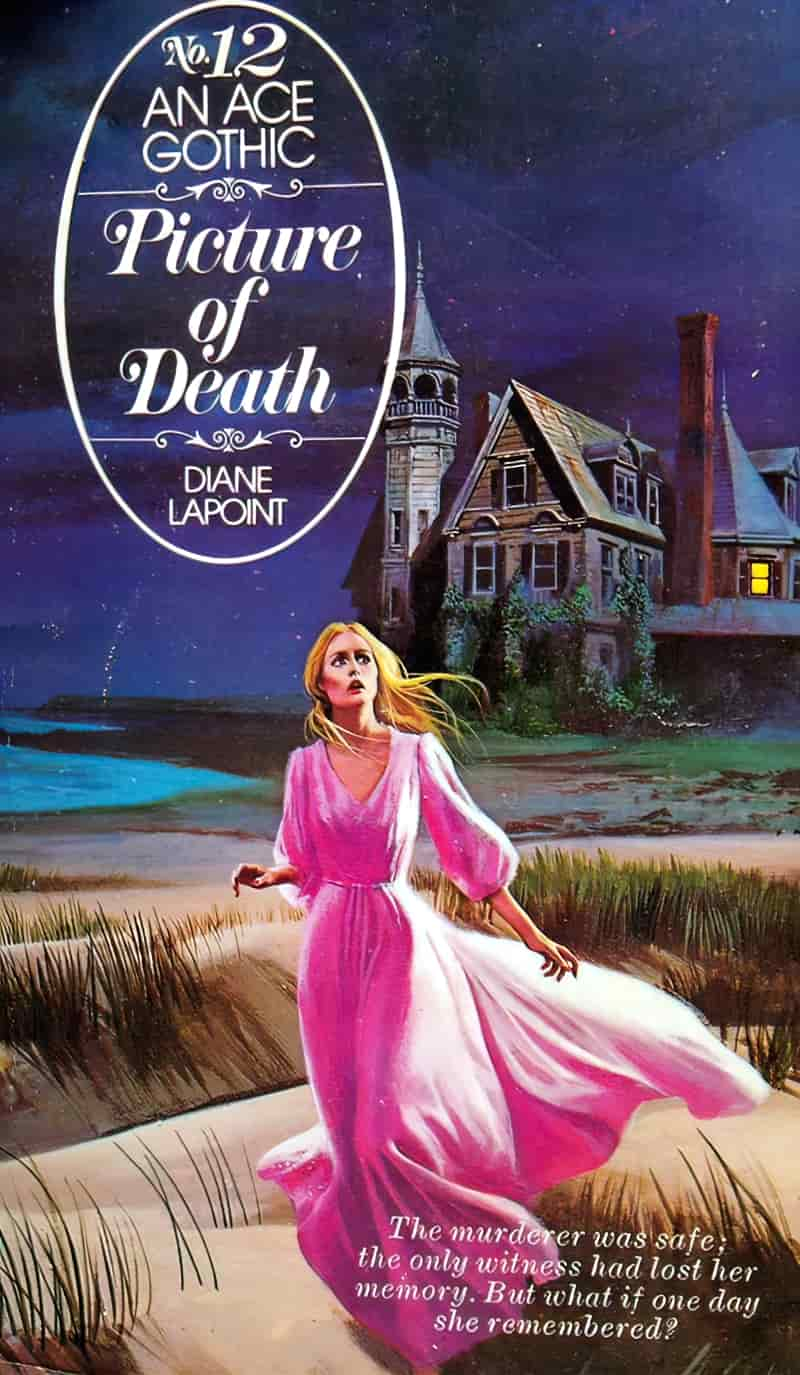

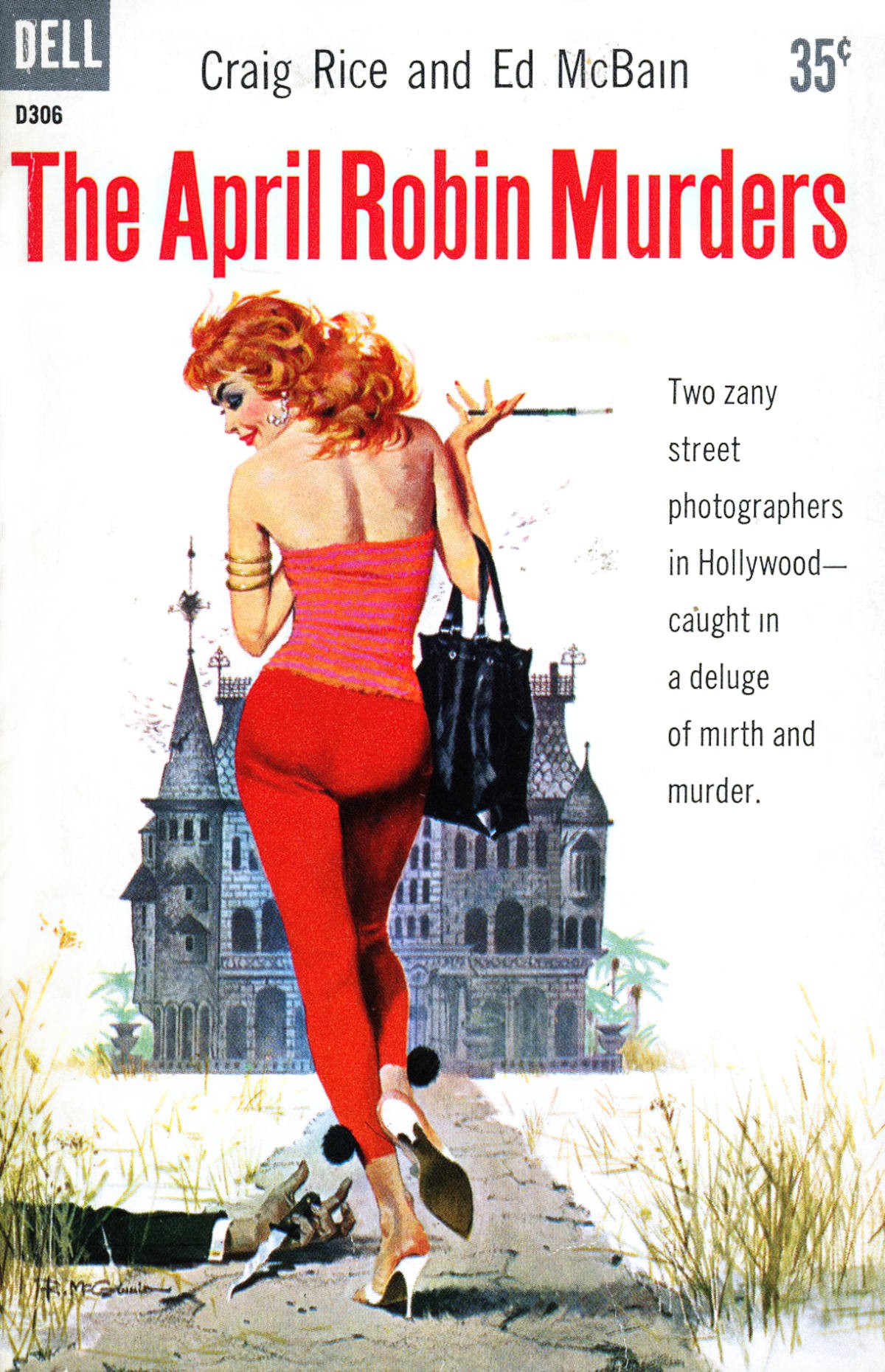

Case in point, the covers of these pulp romances. Each features a woman escaping from a big, terrifying house (and presumably a monster of a man within). I believe Bluebeard is popular in the same way Dirty John popular — tales in which the young woman escapes unharmed from monstrous men reassure us that we, too, will be okay. (Even if statistics say otherwise.)

Marina Warner has written that Bluebeard is a story about a woman’s fear of death via childbirth.

The cannibal is a subject in a gendered plot in which cunning and high spirits win the day, and the boy’s own variety has eclipsed the girl’s in such stories’ transmission since the seventeenth century. Tales of the ‘Beauty and the Beast‘ cycle menace their heroines with death by engulfment, and this obliteration, where a woman’s body is in question, often means sex or childbirth.

No Go the Bogeyman, Marina Warner

This suggests that Bluebeard stories were told for women, by women — with childbirth being a peculiarly female fear. There are other tales which threaten death to female characters (and readers) with ‘death by engulfment’. Warner includes the Beauty and the Beast tales in this category.

When it comes to death by engulfment stories, we can go back further in the history of storytelling, to the tale of Psyche. Psyche’s sisters explicitly warn that her mysterious bridegroom is probably a monster who wants to eat her, especially if she becomes pregnant, as such tender meat delights beasts.

These feminine ‘death by engulfment tales’ contrast with the male analogue, in which a male character sets out to defeat an ogre and always wins by fighting his own big struggle against it. The ogre’s appetite exists to test the hero’s mettle — strength and cunning. These are about social betterment, not of psychosexual anxieties. Sex and marriage has always been more risky — and therefore more scary — for women.

Pixar’s film Brave is a modern, bowdlerised version of the ‘death by engulfment’ story. In that story, Merida is afraid of becoming her mother. She is afraid of being consumed by her mother, too, should the mother turn fully into a bear. This is a different take on the fear of childbirth story and is better tailored to a cohort of girls who will have some (though not full) autonomy over their own reproduction.

STORY STRUCTURE OF BLUEBEARD

WEAKNESS

The woman of the story “his wife” finds the Bluebearded man next door creepy. Not only does he have a blue beard but his wives have kept disappearing without a trace. Her shortcoming, according to this story, is that after he goes out of his way to groom her by throwing lavish parties, she erroneously decides he’s not that bad after all.

Why is Bluebeard’s beard blue? I posit it’s for the same reason the Wicked Witch of the West was green in the Wizard of Oz film. (This has since caught on.) Blue and green are unnatural human colours, signalling illness and bruises, if anything. These colours signify monsters rather than humans. No one can reason with monsters. One can only try to escape.

I’d like to point out the contradictory messages contained for young women in Perrault’s stories. In Little Red Riding Hood girls are told not to trust their instincts with strangers, as bad men come in all shapes and sizes.

DESIRE

The young woman desires to get married. Let’s face it, in those days she had no choice.

OPPONENT

Bluebeard, the serial killer who gets some sort of sick thrill out of grooming new wives then using ‘reverse psychology’ as a reason to murder them. He is an early iteration of the horror psychopath.

PLAN

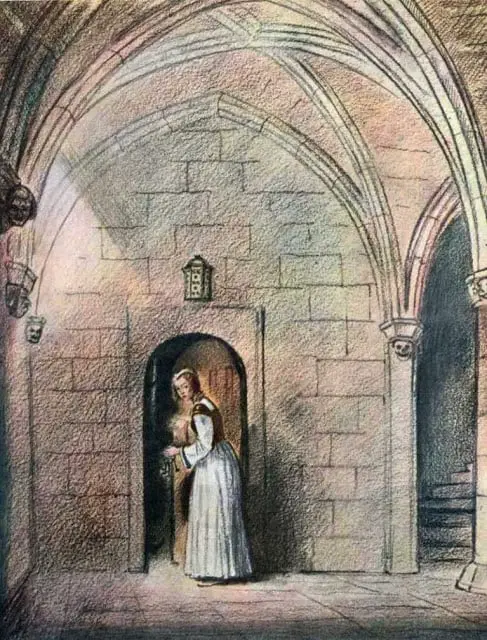

She plans to disobey his order not to unlock a certain door while he is away.

BIG STRUGGLE

The showdown between Bluebeard and the brave brothers, who come to save her with their naked blades.

ANAGNORISIS

She has had a lucky escape. If not for her brothers — a dragoon and a musketeer — she would have been killed. She realises that some men are nasty but can see that others are nice.

By way of the moralistic afterword, young women are warned against being curious. In fact, other versions of this story have added subtitles such as “The Effects of Female Curiosity” or “The Fatal Effects of Female Curiosity”. In the 1600s Charles Perrault was enforcing the message that wives must not pry into the business of their husbands or else they will find out things they don’t want to know. There is a long, long tradition of stories warning women and girls not to be curious. One of the earliest begins in the Garden of Eden, but can be traced through myth (“Pandora”) and fairy tale (“Bluebeard”).

There’s even

a bit of Bluebeard storyline that goes down even in the modern story for adults, Mad Men. In season three, Betty Draper finds the key to Don’s office drawer and finds evidence of a secret past life. This leads to the downfall of her current marriage and to a subsequent marriage to the nice(?) man.

In another very popular AMC TV show we have a plot line which involves a wife’s downfall after she finds out the terrible things her husband is up to. Yes, I’m thinking of Walter White from Breaking Bad. What if writers had kept Skyler completely ignorant of Walt’s doings? One possible reading of that show, particularly in the earlier seasons, is that the less you pry into your husband’s business the happier (and less culpable) you’ll be.

NEW SITUATION

She is now rich, having inherited Bluebeard’s castle. (He has no children — otherwise the castle would have gone to his sons.) She uses some of her inheritance to marry off her sister, Anne, and then remarries, this time to a nice man, like her brothers.

“The Castle Of Murder” is a Bluebeard story from the first collection of Grimm tales. This one has a happy ending which gives the girl more agency than Perrault’s — an old granny in the basement has the job of scraping intestines of the women this psychopath has killed. (For what purpose? No matter. Let’s gloss over that.)

The granny helps the girl escape into a hay cart, which makes me wonder why she didn’t offer the same services all the other maidens who’d been brought to the house. In the end the psycho is brought to justice by the authorities and the escapee inherits his entire castle and marries into the neighbouring family who received her the night she escaped.

The young heroine of “Bluebeard” stories is an early version of what we now call the Final Girl — the only woman left after a whole lot of previous women have been killed before her.

Especially in older works, she’ll also almost certainly be a virgin, remain fully clothed, avoid Death by Sex, and probably won’t drink alcohol, smoke tobacco, or take drugs, either. Finally, she’ll probably turn out to be more intelligent and resourceful than the other victims, occasionally even evolving into a type of Action Girl by the movie’s end. Looking at the Sorting Algorithm of Mortality, you could say that the Final Girl is a combination of The Hero, The Cutie, and the Damsel in Distress — which obviously gives her a very low deadness score. The Final Girl is usually but not always brunette, often in contrast to a promiscuous blonde who traditionally gets killed off.

TV Tropes

RESONANCE

The Bluebeard plot remains popular today in various forms. The Bluebeard story itself has been adapted many times, each one influencing those which come after:

- The opera (libretto) by Michel-Jean Sedaine and Andre Ernest Modeste Gretry (1789)

- The play by Ludwig Tieck, Ritter Blaubart (Knight Bluebeard) 1797

- The play by Maurice Maeterlinck, Ariane et Barbe-bleue (1899)

- The opera by Paul Dukas (1907)

- The opera by Bela Bartok (1918)

- The ballet by Pina Bausch (1977)

- Various musicals and melodramas took the story from England to America between 1785-1815. Bluebeard plays did very well in America. The set designs and costuming of these plays influenced subsequent illustrations in which Bluebeard wields a scimitar and wears the pantaloons of a ‘foreigner’.

- The Germans liked to parody Bluebeard plays.

- Tableaux vivants in 1800s America seemed to revel in the sadism of punishing women for their curiosity, though. These women passively submitted to their death.

- Bluebeard made it early onto the silver screen, with the first film adaptation released in 1901. It was nine minutes long.

- Charlie Chaplin starred in a Bluebeard film in 1947, a silent comedy version called Monsieur Verdoux. This is a predecessor of Dexter, about a man who murders, but who murders for a higher cause. Bluebeard was often presented as comedy until the 1940s. During the war era, Hollywood started to give this story a more serious treatment, using the plot in more covert ways. 1940s Hollywood loved stories about the anxieties of marrying a stranger. This isn’t surprising, since women were frequently getting engaged to men who were promptly sent off to war. When these men returned, they were very often changed people after experiencing the trauma of battle. The Bluebeard plot proved useful for exploring relationships in which the man and woman didn’t know each other.

- Unlike other fairytales (Snow White, The Little Mermaid), “Bluebeard” not surprisingly, tends to find itself adapted for an adult audience. These stories cross many genres, from rom-coms (?!) to film noir. Storytellers can use this plot for burlesque, slapstick and horror.

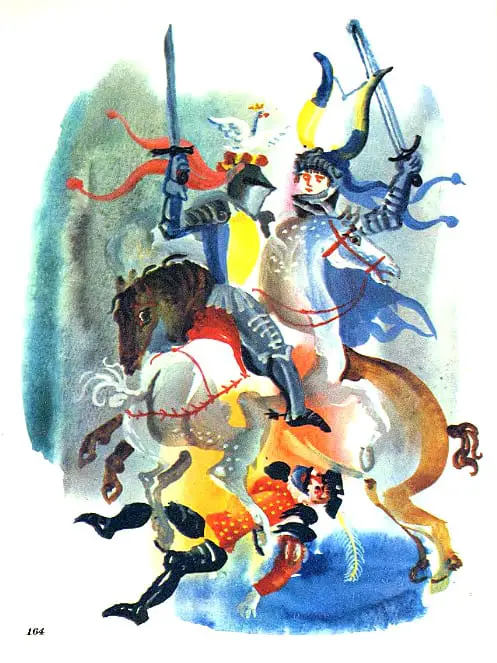

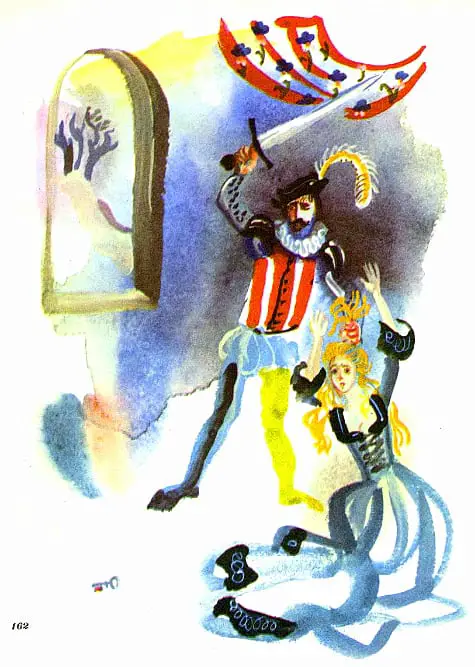

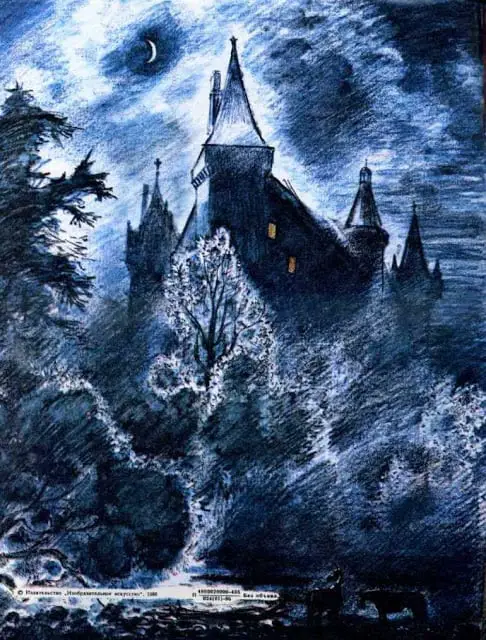

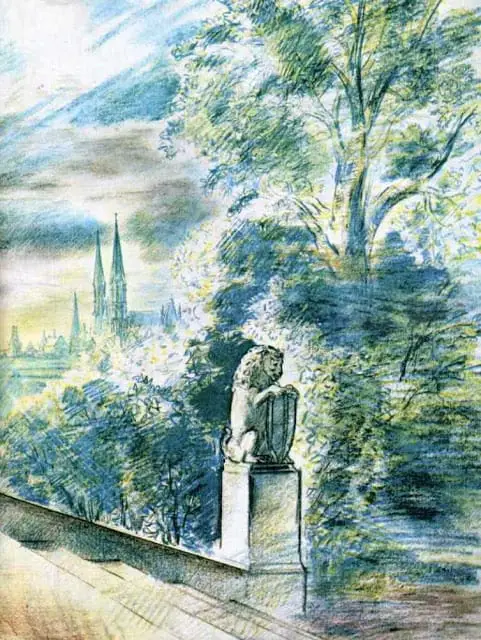

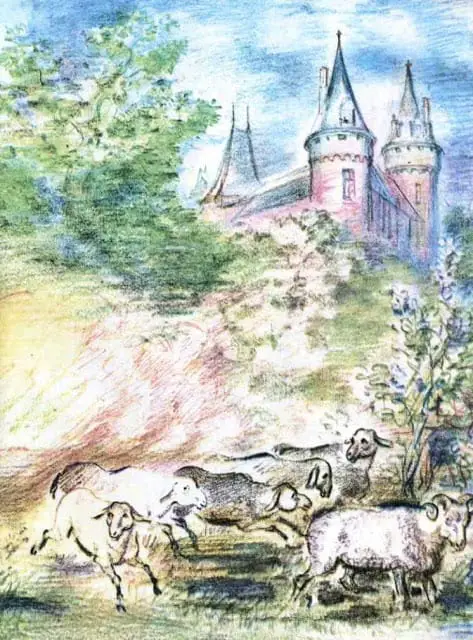

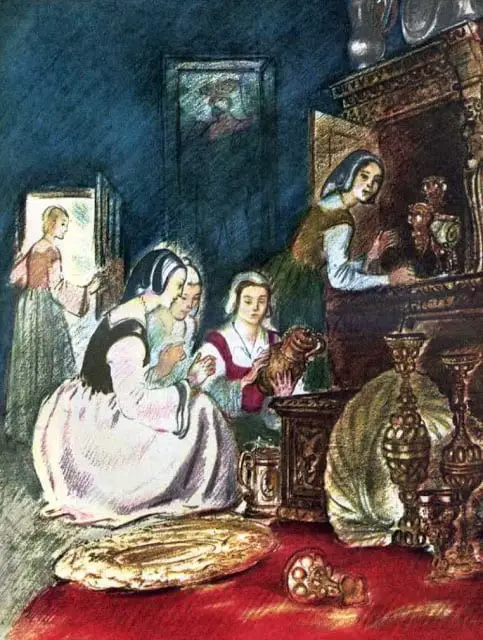

G. Traugot lightened the tale with these naive, brightly coloured illustrations.

Examples Of Stories With Terrifying Big Houses

- Rebecca (itself inspired by Bluebeard), especially Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s novel.

- Gaslight (1944) is a Bluebeard story. Ingrid Bergman plays the character of Paula. There is on-the-page reference to the Bluebeard fairytale in the opening scenes.

- Secret beyond the Door by Fritz Lang (1948), a stand-out example of the so-called ‘paranoid woman films’ aka ‘wife-in-distress cycle’, ‘woman-plus-habitation’, ‘gaslight genre’, ‘Freudian feminist melodrama’. In this story, the wife is a Freudian analyst. “What goes on in his mind?” she asks. In this genre of story, the woman’s job is to find the ‘key’ to her husband’s mysterious behaviour. There is an unspoken assumption that women are expected to ‘fix’ men, even when he’s threatening to kill her.

- Spellbound by Alfred Hitchcock is another example. Dr. Peterson is ‘a love-smitten analyst playing a dream detective’.

- Notorious (1946), another film by Alfred Hitchcock, includes a wife who is more of a sleuth than an analyst.

- Jane Eyre

- Sunset Boulevard

- Stories by Anton Chekhov

- In Cold Blood

- Saturday by Ian McEwan (in a way — we expect the rich to be horrible but McEwan subverts our expectations)

- Twilight series

- Rats In The Walls by H.P. Lovecraft

- Death Of A Salesman

- Mad Men

- American Beauty

- Carrie

- Psycho

- The Sixth Sense

- Big Brother by Lionel Shriver

- Eleanor and Park by Rainbow Rowell

- Sisters by Raina Telgemeir

- Six Feet Under — because the Fishers run a funeral home they keep dead bodies in ‘the basement’. When Clare ventures down to the basement in season one she takes something she shouldn’t.

- The Secret Garden — Mary Lennox is told not to explore the 100 rooms in her uncle’s house, but when she does she finds a cousin who is not dead, but spiritually dying. Author Frances Hodgson Burnett subverts a “Bluebeard” ending by rewarding both Mary and Colin for Mary’s curiosity and her bravery in breaking the ‘rules’.

- The Piano by Jane Campion — I’d be interested to know when “Bluebeard” made it to New Zealand; a darky comic Bluebeard amateur play is the story-within-a-story of this story about a mute woman shipped out to New Zealand to marry a man she never met.

FUTHER READING

- Bluebeard and Mad Men

- Homes and Symbolism In Films and TV

- In The Arabian Nights, Prince Agib has 100 keys to 100 doors and may open them all except the golden one.

- Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums (podcast and book)

Header illustration is by Trina Schart Hyman