“Autumn Day”, a short story by Mavis Gallant, is interesting for feminist reasons. Think of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique; think of Mad Men’s Betty Draper and compare the idle, childlike helplessness of Cissy, the first person narrator in “Autumn Day”. This is a post WW2 picture of American housewives. The men had just saved everyone’s bacon in the war, or so they believed. And after bonding with other men in masculine settings, their wives seemed like foreign creatures.

PLOT

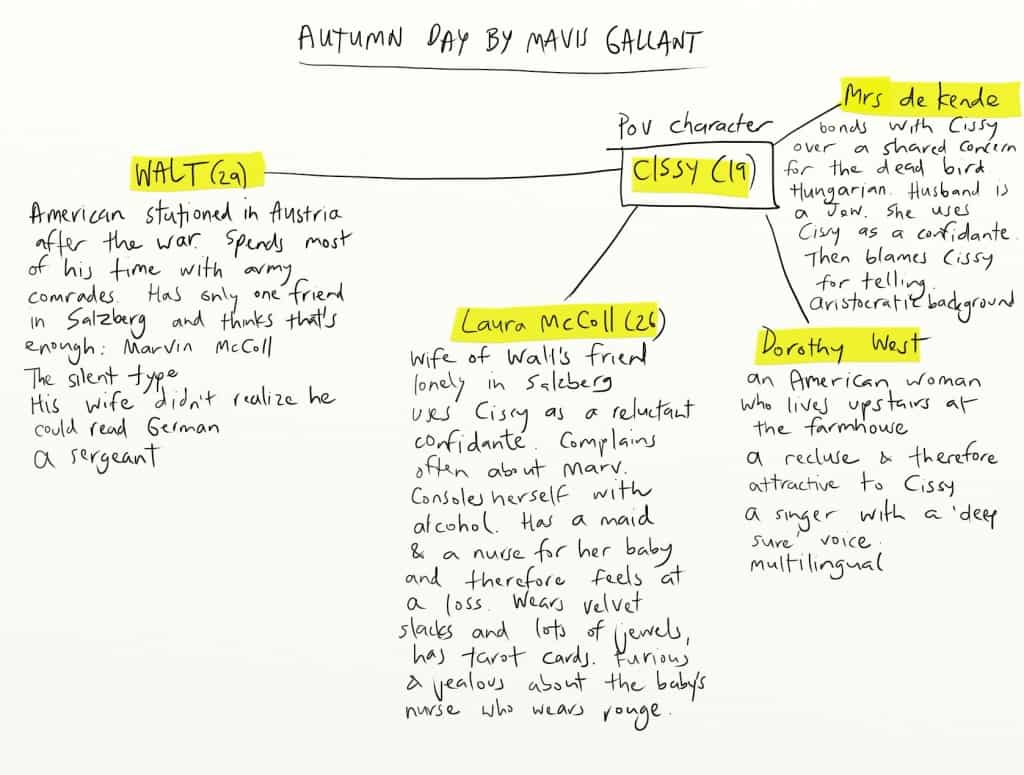

Young and lonely in Salzberg, the newly married 19-year-old Cissy feels estranged from her sergeant husband and fails equally to connect emotionally with any of her local companions.

The wife of her husband’s one and only friend is uncomfortably open with Cissy, letting her in on things Cissy doesn’t want to know. Another woman tells her a big secret and then accuses Cissy of leaking it when she hasn’t. Instead, Cissy is drawn to the reclusive singer living upstairs.

Hoping to meet the singer before she returns to America, Cissy writes her a note, complimenting her on her singing.

The singer invites Cissy to lunch and Cissy is overjoyed to get the invitation, but she is too late; she is given the note the following day and has missed her chance to meet the one woman she thought she might have a connection with.

SETTING

It is seven years since the end of WW2 and Cissy’s sergeant husband has been posted to Salzberg, Austria, as part of the Army of Occupation. (The American army were stationed in and around Germany following each of the world wars.)

The Allied occupation of Austria lasted from 1945 to 1955. Austria had been regarded by Nazi Germany as a constituent part of the German state, but in 1943 the Allied powers agreed in the Declaration of Moscow that it would be regarded as the first victim of Nazi aggression, and treated as a liberated and independent country after the war.

Wikipedia

The story is written from first person point of view by a woman looking back with mature understanding of herself as a 19 year old, so the fictional ‘time of writing’ takes place many years later, perhaps when the narrator is a middle-aged woman. The story itself was published in 1955, 6 years after the events in this story fictionally took place. (Perhaps the narrator is still 25 and has matured considerably in that brief time?)

CHARACTER

In order to emphasise the way a young wife would have typically been regarded, Mavis Gallant emphasised the childlike attitude of the narrator. She first tells the reader how immature the narrator was, then backs this image up with examples (some quite subtle) all throughout the story. The reader is left in no doubt about the naivety, the loneliness and the isolation of the narrator.

Walt is ‘already a little bald’ when she gets off the train that autumn, even though he is still 29. At a youthful 19, a ten year age difference is a lot, and to the childlike Cissy, whose diminutive name is somewhat allegorical. All she sees in her husband is his advanced age.

‘I waved at Walt, smiling, the way girls do in illustrations.’ Cissy still demonstrates the narcissism of youth, in which we define ourselves according to how we must appear to others from the outside looking in. Cissy uses fictional girls in pictures as models for how to act; she has not yet developed her own identity.

Losing a hatbox upset her, ‘nearly in tears’. Concerned with inconsequential material items rather than the fact of moving to a new country to begin life with her new husband should make the reader question her sense of perspective.

Such details continue throughout the story. It is revealed that Cissy doesn’t really consider herself old enough to be pregnant, or how she may have become so. Not knowing whether she is or isn’t, she half-believes Laura McColl when she suggests a possible reason for Cissy’s discontent.

THEME

One theme is revealed in the title. The seasons are commonly used as symbols to mark passages through life, or through some other event, with spring being a time of growth; summer being a time of naivety and happiness; autumn where everything changes (probably for the worse) and winter being darkness culminating in death.

Within the story, on the most surface layer of meaning, Autumn Day is the English translation of one of Dorothy West’s songs, one which resonates with Cissy and moves her emotionally. On a deeper layer of meaning, Cissy is on the brink of maturity, and she is mourning the loss of the girl she used to be.

Weather is often in stories to mean something more than just ‘the weather’. Here, too, the autumnal cloudscape feels oppressive to Cissy. Like a storm coming, she senses something bad is afoot.

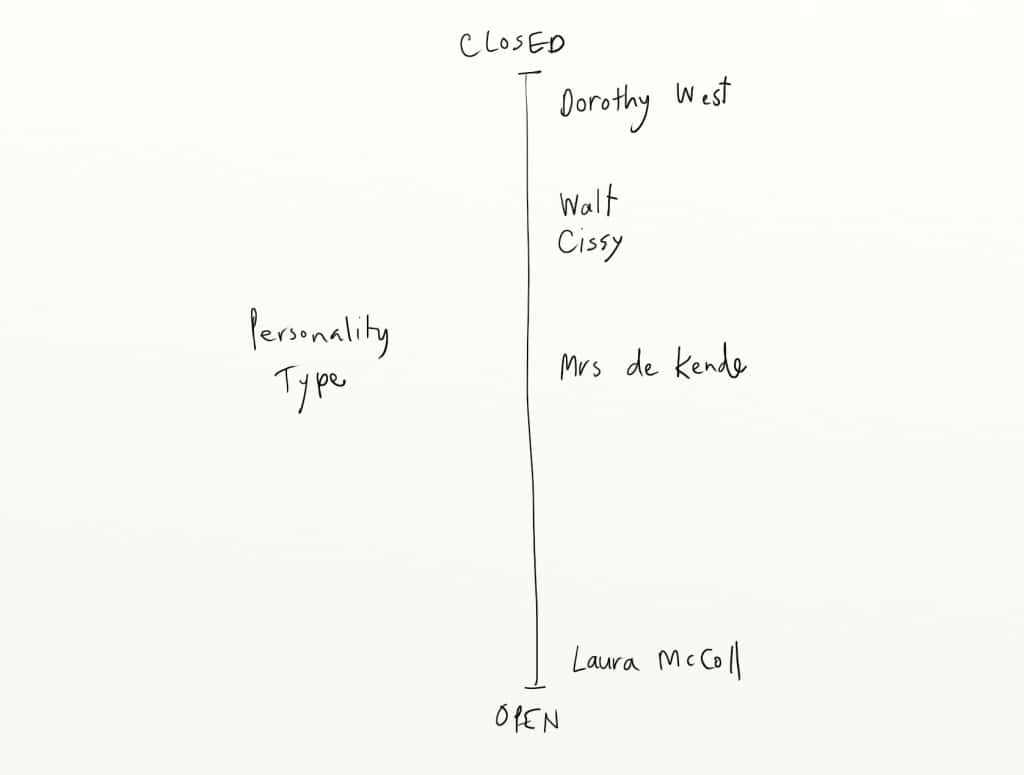

This is also a story about truth-telling versus secret-keeping, with the cast of characters each representing different degrees of possible openness. Dorothy West is the most closed of all, refusing to speak to the other house guests for the during of her stay at the farmhouse. Cissy herself comes next, drawn to the secretive world of Dorothy West. Dorothy West, it is revealed, speaks four languages. Dorothy West is obviously a mature woman of the world who knows things, and Cissy is longing for an older mentor. Cissy’s husband Walt is equally reserved, revealing nothing of himself to his young wife, including the fact that he can read German, for example. Mrs de Kende is charged with the task of keeping a grave secret, but is not naturally suited to the task. Mrs de Kende sees in Cissy what Cissy sees in Dorothy West — a confidante who can keep secrets. They bond over a single incident. When a small bird is thrown into the fire, Mrs de Kende sees Cissy’s discomfort, and extends the metaphor to assume that Cissy is equally sympathetic to the plight of the Jews, who (in a not-so-subtle) metaphorical way were murdered en masse in similar fashion. Existing mainly as an antithesis to Cissy is Laura McColl, who not only talks incessantly to Cissy about the problems in her marriage but speaks rudely about the nanny in front of the nanny (who may or may not understand enough English to realise).

This is an interesting story because it bucks a certain trope: The most open characters in stories tend to be the most likeable. Readers identify more easily with those who we can easily ‘read’, who share the most. But in this particular story, the most open of them all is also the least likeable. This partly explains Mavis Gallant’s choice to write in first person point of view. Being such a private person, Cissy might have been a little harder to identify with if we were not allowed to see her exact point of view.

I’m impressed by how the story still feels very modern, and equally disappointed that even today there is a myth (clearly demonstrated in rape culture, for example) that women, as a species, are basically liars. Cissy’s husband warns her not to listen to anything Laura says about her husband, not because Laura has her own particular problems, but ‘because women talk about their husbands’. Cissy is offended by this but can’t at the time articulate why. Her reasons for taking offence are left for the reader to interpret: Cissy is a woman and does not betray confidences regarding her marriage; therefore this statement about ‘women in general’ is incorrect and unfair.

STORY SPECS

Approx 5100 words

First person POV from perspective of the narrator who has matured and is looking back on her youth

Written in 1955

Published in The Cost Of Living

COMPARE WITH

“Prelude” by Katherine Mansfield features the character of Beryl, who exhibits the same sort of narcissism of youth. She looks at herself in the mirror, imagining what she must look like to someone else. Both Mavis Gallant and Katherine Mansfield convey this feeling in a masterful way.

Lost In Translation starring Scarlett Johannsen and Bill Murray is a film which conveys the feeling of loneliness which comes from being cooped up in a room in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language and have no close friends.

WRITE YOUR OWN

A time you were in a situation where no one was like you

A person you felt somehow connected to but who you never had the opportunity to know, and who you’ve thought of a lot since

A milestone passage in life, which marked some sort of boundary between immaturity and maturity, regardless of actual age