The more you read of [Shields’] stories the more you sense her delight in making connections, moving things on…If Shields had a single subject in these stories it was really solace, the strategies we employ to keep despair, or doubt, or even confusion at bay. Mostly that solace comes from language, whether it be literature or everyday wisdom…She dwells a lot on the singularity of couples, the flimsiness of the ties that bind, the minute-by-minute work of strengthening them.

The Guardian

What Happens in “Accidents”

A husband and wife take a vacation on the French coast, as they do every year. The wife is a translator and we find out near the end of the story that the husband narrator is an abridger. When a cup on the verandah of their accommodations seems to spontaneously explode, the husband moves close to reassure his wife, but she turns her head unexpectedly and her earrings leave a surprisingly deep gash across his cheek. He must spend a night in hospital. In the next bed lies a young man covered in bandages. The young man has been in a motorcycle accident and eventually dies, leaving the holidaying husband and wife to get on with their holidays. The husband manages to move on from this shock by telling his wife the man has ‘moved on’, without elaborating that he has actually died.

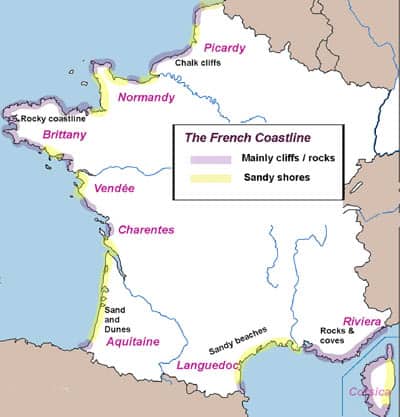

Setting of Accidents

This middle-class Canadian couple holiday on the French Coast. They stay in a comfortable vacation flat owned by the wife’s brother-in-law.

Although the husband grew up in French-speaking Montreal, there is a language barrier in which he realises he can’t pick certain speakers’ French irony. This creates creates an uncomfortable tension via the setting, for both the character and the reader; how much of this story itself is ‘true’? Likewise, how much can the reader trust this first person narrator?

The place this couple visits every year is called Aigues Mortes, which unfortunately includes the French word for ‘dead’ (part of the plot) but is also thematically significant because it is a fort: A symbol of the state of this couple’s marriage, the way things look safe on the outside but only because certain topics are not broached.

Characters in Accidents

“Accidents” opens with a character sketch of the narrator’s wife:

At home my wife is modest. She dresses herself in the morning with amazing speed. There is a flashing of bath towel across the fast frame of her flesh, and then, voila, she is standing there in her pressed suit, muttering to herself and rummaging in her bag for subway tokens. She never eats breakfast at home.

This thumbnail character sketch is adept, and often used in novels as well as short stories, but on second reading — after I know the narrator is an abridger by profession — I wonder just how much has been abridged. Something of the ‘speed’ that abridgement offers is conveyed even in this sketch with the ‘flashing’ of bath town, and ‘fast frame of her flesh’ (whatever that means, exactly). The verb ‘rummaging’ includes the meaning of rapid motion. This is a modern-day working martyr, never eating breakfast at home — a modern-day fast, perhaps. The narrator later compares her to St Agatha, a Christian martyr. Is this how he thinks of his wife?

The narrator himself paints himself as a loving husband who is attentive to his wife’s needs. ‘I was anxious to reassure her,’ he says, which is how he ended up with a deep gash in his cheek. He appreciates that his wife removed her earrings after that. Yet there is something unsettling about a husband who sees his wife’s bare breasts and is put in mind of a rather disturbing Spanish Baroque painting of St Agatha (below). There is also something unsettling about a husband who sees his middle-aged wife as someone to be protected from the truth. Although the small untruth in this story is innocent, what else is going on in their wider lives outside this oasis of holiday? How might an abridgement of reality impact their relationship?

THEME

For a queasy reader such as myself, “Accidents” is an uncomfortable read. We are confronted with the flesh, cut and dismembered, as foreshadowing for the death which occurs at the end.

There is truth and then there is the whole truth. The whole truth is not always necessary or pleasant.

Innocence and age are sometimes the same thing.

Tragedy exists alongside the minutiae of everyday life, and sometimes we are oblivious to the tragedy, distracted by the minutiae.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

Although the narrator is an abridger, he includes certain details which at first glance don’t seem necessary to the flow of the story, signs that he is ‘abridging’ the whole story for our benefit. We are told not only that the cup explodes, but that it is ‘made of a sort of tinted glass in a pattern that can be found in any cheap chain store in France.’ This is the sort of detail that aims to lend verisimilitude, but also distracts us from whatever else might be going on. Did the cup really explode or did someone throw it? Why? The narrator is showing us with such details that his story is to be trusted.

Was it really the earring which gashed his face? Here in Australia, the court case of Gerard Baden-Clay comes uncomfortably to mind. Baden-Clay murdered his wife. He attempted to explain away a deep gash on his face as a self-inflicted shaving accident.

When the wife in this story goes shopping, she buys ‘a new pale cardigan with white flowers around the neck, very fresh and springlike.’ This is the cardigan of a ‘fresh-faced’, nubile young woman — a woman who needs to be protected from the truth. Even the holes in her earlobes are described using the child-associated word ‘dimple’, rather than say, ‘holes’ or ‘tiny gashes’ or any number of more grisly alternatives.

This image of the wife as young and fresh is followed by a paragraph about the newspaper, in which we are reminded that this is not actually a young woman at all: The last time she bought the Herald Tribune was in 1968, which at the time of the story makes her middle-aged.

All of these details tell the reader that our narrator sees his wife as a young person, and explains his withholding (‘abridging’) unpleasant information at the end. This naturally makes him an unreliable narrator, despite all his details.

STORY SPECS

Originally published in the anthology Various Miracles, Accidents also appears in the Collected Stories, published one year after Shields’ death in 2003.

COMPARE WITH

Any suggestions?

WRITE YOUR OWN

Sometimes in stories — as in real life — the career/job/vocation of a person can influence the way they conduct their personal affairs. Think of some lesser-known/more mysterious jobs. How might the mindset required for such work impact a character’s life outside work? Can this become a story?

Have you ever omitted part of a story for the sake of others?

Does the uncomfortable abutting of triviality against death in this story remind you of any real life situation?