ABOUT THE STORY

Written in the early 1960s, “A Glutton For Punishment” is about a man who gets the sack from an unspecified office job in New York City. He considers keeping this information from his wife.

SETTING

In this post-Mad Men era, it’s impossible to read Yates and not envisage scenes from Mad Men.

Yates’s revival might simply be one example of our current fascination with mid-century America. Another example — or cause — of this fascination is Mad Men, which recently won the Emmy Award for best drama series, and has replaced The Wireas the show serious-minded people watch seriously and write about seriously in serious-minded publications.

Bookslut

The hustle and bustle of New York, in which everyone seems to have somewhere to go, contrasts against the aimlessness of Walt as he struggles with what he is to do and where he should go now that he is between jobs.

Walter Henderson works on Lexington Avenue. Here’s a photo from the mid-seventies:

This collection, first published in 1962, pinpoints, like a lepidopterist, a particular epoch in American history – the postwar world of dissatisfied veterans, young men swaying uneasily on the lower rungs of the career ladder, married to unsatisfactory women without whose typing job they would be destitute; ambitious but miserable young writers trapped in inappropriate jobs; unglamorous pre-dinner martinis, jazz bars, teachers despised by their pupils….can describe a world, and the state of mind it creates, so economically, so persuasively, that you stay your hand even as it reaches for the full bottle of paracetamol or opened razor.

from The Guardian Review of Eleven Kinds Of Loneliness

CHARACTERS

If you’ve read Yates’ most popular novel, Revolutionary Road, you may feel that the character of Walt is familiar — to me he seems like a mish-mash of the two main male characters of Revolutionary Road: Frank Wheeler and Shep Campbell. Like Frank, who gets up before his wife each morning so that he can compose himself into the man he thinks April needs him to be, Walt is careful to shield his inner turmoil from his wife. But Walt’s life situation is more like that of Shep, who has a big family to care for, weighing down on him, and a wife who he has started to view as unattractive.

In a short story, characters — even main characters — must be painted with a few deft strokes. In this case, we get to know Walter first as an uncoordinated, rather melodramatic boy. When we meet him as an adult, our view is coloured by what we know of him as the boy, but we are told that underneath the show of manhood, he is still the same boy:

He had become a sober, keen-looking young man now, with clothes that showed the influence of an Eastern university and neat brown hair that was just beginning to thin out on top. Years of good health had made him less slight, and though he still had trouble with his coordination it showed up mainly in minor things nowadays, like an inability to coordinate his hat, his wallet, his theater tickets and his change without making his wife stop and wait for him, or a tendency to push heavily against doors marked “Pull.” He looked, at any rate, the picture of sanity and competence as he sat there in the office.

In just one long sentence followed by a short one, we learn all about adult Walt that we need to know. Note how deftly the following information was inserted, seemingly as an aside:

- He is one of the All-American privileged, with a university education and in good health

- He is married

- He has middle-class interests such as going to the theatre

THEMES

Gender is a performance, learned around the time of adolescence.

To this female reader, A Glutton For Punishment seems to be first and foremost a story about the performance of masculinity. Femininity, too, is a performance, and people who perform their gender most carefully do seem to find each other. Walt’s wife performs femininity on the couple’s first date, when she waits at the top of the library steps just so her date will have to greet her by climbing up to her pedestal. This is the foundation upon which their relationship has been built, even though they have shared their secret motivations about that first date since getting to know each other. In some ways, nothing has changed. Walt sees his job as the breadwinner and protector of his family. When his wife sees through his mask of composure, she is no longer attractive to him — what he seems to want from a relationship is one-way support: It is his job to shield the woman from life’s stressors, such as firings. It became a matter of individual performance, almost an art, Yates writes of the childhood game of falling down dead, but he is equally describing the man’s role in a marriage.

These adult roles are learned at some time during childhood. For Walt, his adult-socialisation began in earnest when some older boys laughed at them for playing their falling-down-dead game.

The idea of mystique in a long-term relationship may be alluring, but you can’t keep it up.

Though we tend to think of women (Marilyn Monroe types) when we think of mystique, or perhaps because of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique which, not co-incidentally, was published just one year after this collection of short stories. Just as women were told that the pinnacle of happiness could be found in immersing themselves fully in home and family, men at this time had equally rigid expectations heaped upon them: Their role was to support this single breadwinner lifestyle. Just as women were expected to hide their longing for autonomy and professions, men were expected to completely mask their emotional vulnerabilities, even to their wives.

There are privileges that come with masculine autonomy, and with great privilege comes heavy responsibility.

We see this time and again on Mad Men — a male worker is fired and his female secretary is reassigned. The female secretaries, of course, earned very little in comparison to the men, all of whom play in a high stakes game. When Walter Henderson tells his secretary not to worry, that they’ll find her another position, the juxtaposition between their situations is stark: She seems lucky because she will have a job tomorrow; on the other hand, she will never be more than a secretary. Her real job is no doubt to find a husband and start a family.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

Two Eras Of A Character Make For A Fuller Character Study

Many stories either dive straight into the action of the story or keep any backstory for chapter two. (Or in a short story, backstory tends to be dished out in small quantities and the author hopes it’s sufficiently interesting so as not to interfere with pacing.) A Glutton For Punishment is quite different because we meet the boy before we meet the man.

There are several reasons why this story structure has been chosen:

- Boyhood comes before manhood, so this is a logical sequencing

- This is a story about masculinity, and the era before the masculine performance is significant as a counterexample — a boyhood in which ‘falling down dead’ was no more than a game.

The Ending Matches The Beginning To Present A Clear Juxtaposition

From the beginning: Then the performer would stop, turn, stand poised for a moment in graceful agony, pitch over and fall down the hill in a whirl of arms and legs and a splendid cloud of dust, and finally sprawl flat at the bottom, a rumpled corpse.

The final sentences: His right hand came up and touched the middle button of his shirt, as if to unfasten it, and then with a great deflating sigh he collapsed backward into the chair, one foot sliding out on the carpet and the other curled beneath him. It was the most graceful thing he’d done all day. “They got me,” he said.

There’s much that is comical about the description of the nine-year-olds’ game of falling down dead: Back then, it ‘was the very zenith of romance’. Then there is the slapstick-type description of the actions and sounds made by the boys. This of course exists to contrast with the adult reality of getting fired while a breadwinner; an altogether more serious challenge.

Humour, too, serves as juxtaposition against the sadness.

Yates is often called a ‘depressing’ writer, but most of these stories are as equally humorous as they are sad.

Angela Meyer at Crikey

Just the right amount of telling versus showing

It’s easy to fall prey to the idea that when writing a short story you must show every single thing, but this story is a prime example of what is best told rather than shown. Take the sentence that segues us from the childhood era to the present:

But he had occasion to remember [the childhood play scene], vividly, one May afternoon nearly twenty-five years later in a Lexington Avenue office building, while he sat at his desk pretending to work and waiting to be fired.

We are not shown much of his firing, and not told why he is being fired, because this is not the interest point of the story.

STORY SPECS

A Glutton For Punishment is the fifth story in Yates’ collection Eleven Kinds Of Loneliness, which was published very soon after he wrote Revolutionary Road. This story is very much from the world of Revolutionary Road.

Written from close third person point of view, focusing on the character of Walt. This allows the reader to empathise mostly (if not entirely) with Walt. We are inclined to empathise with a character who suffers some misfortune right at the beginning of a story — and of course this is not the beginning — we as readers have no idea what has prompted the firing. If we’d been let in on the extent of his incompetence, we may feel less warmth towards him, and more annoyance.

One of Yates’ biggest strengths is the way he gets you in so close to the characters – so close you can hear their thoughts and plans and see their hearts ticking – yet simultaneously at a distance so that you may see how they are perceived in the greater scheme of things. Yates suggests both compassion and pity through this kind of writing – and not just for the characters on the page, but for the person sitting next to you, and even for your own stupid, small (and often joyous) existence.

Angela Meyer, Crikey

COMPARE AND CONTRAST “A GLUTTON FOR PUNISHMENT”

While Mad Men is the more obvious TV analogue, in which Don Draper has literally stolen another man’s identity — a metaphor for the way in which men of mid-century America were forced to cultivate both a public and private, hidden self, I would like to consider for comparison a very popular TV series with a modern setting.

Perhaps it’s partly because the main characters share the same first name, but Walter Henderson from A Glutton For Punishment faces the same challenge to his masculinity as Walter White of Breaking Bad, especially the Walter White of season one (before he ‘breaks bad’):

- Walter Henderson gets the sack for poor performance; Walter White is under-utilised, underpaid and disrespected by his students.

- Walter Henderson hides his sacking from his wife, hoping to work things out on his own; Walter White hides his diagnosis of lung cancer from Skyler, hoping the same.

- Walter Henderson feels he walks around with a thin veneer of calm, but his lack of co-ordination sometimes betrays him; Walter White is an intellectually clever science geek who is disrespected by alpha male types, exemplified by characters such as Hank. Walter Henderson…was a slightly, poorly coordinated boy, and this was the only thing even faintly like a sport at which he excelled.

- Both of the Walts have wives who can see when something is wrong. This annoying astuteness makes the wives less attractive to the men (and in the case of Breaking Bad, to much of the masculine viewing public, also). Though the eras are different, the household roles are the same: both of the Walts keep out of the kitchen, supporting stay-at-home-Moms who look after the family. (I have wondered why Skyler isn’t working outside the home in the lead up to her second birth — this is a plot convenience rather than a realistic one, given that the family is struggling to make ends meet.)

Of course, Walter White takes a lot longer to admit defeat than Walter Henderson does — in fact, it takes five seasons of action before he admits that he is motivated by the need to prove his masculinity, and therefore his worth, to himself.

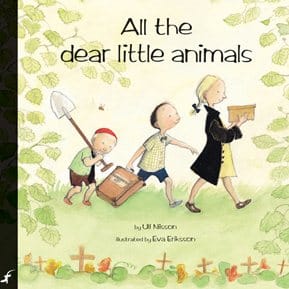

The first section of A Glutton For Punishment is about the innocent fun of childhood games, and the way in which children sometimes process the issue of death (and general failure) by incorporating dramatic scenarios into their free play. In this respect, the first part of A Glutton For Punishment is reminiscent of All The Dear Little Animals by Ulf Nilsson, in which a small troop of children go to great lengths finding dead animals and giving them funeral services.

WRITE YOUR OWN

Looking back on your own childhood, did you play games which now seem a little off-kilter? What life issue were you trying to come to terms with by playing these games?

Is there a part of your childhood self that you feel is masked most of the time, but which sometimes reveals itself in certain situations?