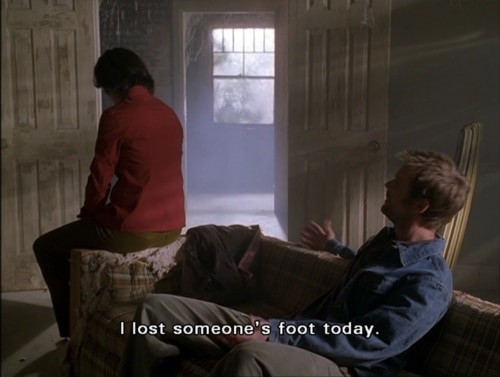

At around the same time Annie Proulx published “The Blood Bay”, an episode of Six Feet Under saw Claire in big trouble for stealing a severed foot from her family’s funeral business and taking it with her to school. That episode, like this story, was darkly funny and made use of someone’s severed foot.

It was inevitable that a TV series called something about feet would have to at one point make use of an actual foot. Dark comedy involving the loss of someone’s severed foot was used more recently in episode seven of season two of Animal Kingdom. (“Dig”)

While this is icky, North Americans haven’t been so squeamish about carrying around rabbits’ feet for good luck. Larry McMurtry writes of that practice in his cowboy novels. (Only the left hind foot is lucky.)

Severed human hands have a stronger history in folklore than severed feet. Characters with severed hands tend to be either victims, or monster-like villains. For more on that see Severed Hands as Symbols of Humanity in Legend and Popular Narrative by Scott White. The severed, walking hand also makes for a memorable horror scene.

SETTING OF “THE BLOOD BAY”

The year of this story — the winter of 1886-87 — is offered first thing, because there’s something the author needs us to understand from the get-go: This is a tall tale and it supposedly happened a long time ago. This means the tale might not be terribly true. It is sure to have been embellished as it was handed down the generations. It’s not just the year itself which is significant, but the long-agoness of it.

If you’ve read Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove series, the final two books take place around about the same era. This is the era of the Wild West, of cowboys, where life is pretty cheap but boots cost an arm and a leg. It’s humans up against the weather, where farmers eke out a living without the conveniences and technologies enjoyed today by farmers, who still have bad years even now.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE BLOOD BAY”

It’s not easy to pick the main character in some of Annie Proulx’s short stories. That’s because, by her own admission, she doesn’t tend to write about people but about entire communities. Take Brokeback Mountain. That’s about a homophobic society more than it’s about Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist. Likewise, this is a snapshot of cowboy culture, in which death is so common that it might even happen that an old man be so easily fooled.

So I will try to make out the story structure using the cast of characters rather than taking a single hero.

This story makes use of what might be called a McGuffin — one of Hitchcock’s storytelling terms. Once that initial dude with the fancy boots succumbs to hypothermia readers don’t give him a second thought. His journey was used to get the story going. That’s a McGuffin.

SHORTCOMING IN THE BLOOD BAY

In this environment the human inhabitants are at a huge disadvantage: They’re never very far from death. That’s their biggest shortcoming, and is common to Proulx’s Wyoming stories.

The cowboys don’t have much money but they do need to stay the night. They feel they’ve been ripped off. If money were no object, this story wouldn’t fly. Poverty is at the base of most of Proulx’s Wyoming stories.

The farmer’s biggest shortcoming is that he’s gullible, though this fact is kept for the punchline at the end.

The cowboys are based on the trickster archetype from fairytales — still a very popular archetype in modern stories. But there’s a twist — these guys never set out to be tricksters — they are opportunists who don’t speak out when they see things swinging to their advantage. That describes many of us, doesn’t it?

DESIRE IN THE BLOOD BAY

The cowboys want to get somewhere. One of them needs new boots. (We’ve already seen how perilous it can be to travel with substandard equipment.) The farmer needs to earn a living and he does this by taking in cowpokes and charging them for room and board.

OPPONENT IN THE BLOOD BAY

The cowboys are at odds with the farmer because they feel they shouldn’t have to pay that amount for one night’s room and board.

PLAN IN THE BLOOD BAY

One cowboy rides off early having failed to politely dispose of the thawed feet cut from the fancy boots.

The other two have no plan other than to keep mum once the farmer wakes up, finds the feet and refunds their money.

BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘big struggle’ scene is the discovery of the feet. It works beautifully because of Annie Proulx’s wonderful dialogue:

“There’s a bad start to the day,” he said, “it is a man’s foot and there’s the other.” He counted the sleeping guests. There were only two of them. “Wake up survivors, for god’s sake wake up and get up.”

The two punchers rolled out, stared wild-eyed at the old man who was fairly frothing, pointing at the feet and the floor behind the blood bay.

“He’s ate Sheets. Ah, I knew he was a hard horse, but to eat a man whole You savage bugger,” he screamed at the blood bay and drove him out into the scorching cold.

ANAGNORISIS

It’s a wonderful touch that the farmer is secretly proud that his horse can eat most of a raw cowboy. But I wouldn’t call this any kind of revelation — the farmer is duped and remains so.

The reader is reminded of the harshness of this milieu. The cowpokes don’t put the old man out of his misery, and why bother? People die out here all the time. There’s no real moral dilemma for them.

NEW SITUATION

The farmer is down a night’s room and board. Two of the cowboys got a free night with good food. The other ended up with nice boots.