Shopping malls play a big part in many people’s lives. Naturally, malls make it into fiction, sometimes prominently. How are storytellers making use of malls as setting?

What did we have before malls? The City Square.

Victor Gruen was the architect of the first shopping mall. He proposed mall as a basic unit of urban planning, where the mall becomes a multi-purpose city center. He identifies shopping as a part of a larger network of human activity, arguing that the selling would be better if commercial activities were integrated into the cultural and entertaining activities. Gruen saw designing of shopping malls as a way of producing new urban centers or, as he called them, “shopping towns.” He was encouraging designers to program a shopping mall which included many shopping activities, as well as cultural, artistic and social events. He labelled this social integration of commercial activities “architecture of the environment.”

SHOPPING MALL VS. OPEN PUBLIC SPACE IN CONSUMER CULTURE, Aleksandra Djukic, Marija Cvetkovic

The first [American] shopping mall was technically an outdoor shopping plaza that opened in 1922 in Kansas City. However, the first indoor shopping mall that mirrored how we think of malls today was opened in 1956 in Edina, Minnesota. Malls were often anchored by a large department store with a cluster of other stores around it.

Big Commerce

The shopping mall has not just changed how we shop. The mall is what allows suburbs to exist, further and further away from the central business districts of cities. Plonk a mall down, change the actual landscape for miles around.

Depending on our definition of ‘mall’, they go back a long way. Ancient Greeks had a public open space used for assemblies and markets called the agora.

Over time, malls have continued to expand the services and entertainment on offer. By the beginning of the 21st century, American-style malls were looking less like shopping precincts and more like mini-cities.

Malls are not a monolith. Here in Australia, suburban malls all tend to look the same. They each contain the same mixture of chain stores and, in many cases, you’d be hard pressed to know where in Australia you were if you were guided to a mall blindfolded. Sydney’s Pitt Street Mall is one of the most expensive in the world. This mall is in the central business district, and isn’t like Australia’s famous Westfield malls, but is better described as the pedestrianised section of Pitt Street. Despite being the seventh most expensive place to shop in the world, it contains the same chain stores as Australia’s suburban malls.

East Asia and Europe also tend towards ‘covered passageways’ of shopping rather than mini-cities. Still, we tend to call any roofed-in shopping area a ‘mall’.

Arabic and Somali speaking countries have the ‘souk’ (street marketplace). We might also use the word ‘bazaar’ to cover a broad range of retailers coming together in a street-like formation. The English have ‘arcades’ (though here in Australia ‘arcade’ calls to mind noisy gaming parlours for kids, with coin-operated machines.

Arcade Britannia: A Social History of the British Amusement Arcade

The story of the British amusement arcade from the 1800s to the present.

Amusement arcades are an important part of British culture, yet discussions of them tend to be based on American models. Alan Meades, who spent his childhood happily playing in British seaside arcades, presents the history of the arcade from its origins in traveling fairs of the 1800s to the present. Drawing on firsthand accounts of industry members and archival sources, including rare photographs and trade publications, he tells the story of the first arcades, the people who made the machines, the rise of video games, and the legislative and economic challenges spurred by public fears of moral decline.

Arcade Britannia: A Social History of the British Amusement Arcade (MIT Press, 2022) highlights the differences between British and North American arcades, especially in terms of the complex relationship between gambling and amusements. He also underlines Britain’s role in introducing coin-operated technologies into Europe, as well as the industry’s close links to America and, especially, Japan. He shows how the British arcade is a product of centuries of public play, gambling, entrepreneurship, and mechanization. Examining the arcade’s history through technological, social, cultural, biographic, and legislative perspectives, he describes a pendulum shift between control and liberalization, as well as the continued efforts of concerned moralists to limit and regulate public play.

Finally, he recounts the impact on the industry of legislative challenges that included vicious taxation, questions of whether copyright law applied to video-game code, and the peculiar moment when every arcade game in Britain was considered a cinema.

New Books Network

Parisians and Italians have galleries. Russia has GUM, the main mall in many of its cities. (GUM is an acronym and stands for ‘Main Universal Store’.)

Kath and Kim shows that Australian malls don’t discriminate. Pretty much everyone who lives in a city visits the mall, even if it’s once per year.

In other parts of the world, the difference between high-end and low-end malls is stark. Mumbai has an good example of this divide. In Phoenix Mills, Lower Parel you’ve got Palladium (a.k.a. The Atrium). Check out the website. It looks like a super fancy airport shopping area. You won’t afford anything there unless you’re wealthy.

If you’re not stinking rich, you’ll have more luck at the mall next door, called High Street Phoenix Mall. (It has ‘high’ in the name, but this is the low-end version.) The High Street mall is where you’ll find McDonalds and other chain stores and restaurants.

THE MALL AS PARADISE

An event like Black Friday makes hundreds of people in the United States stand in line in shopping malls all over the country. Typically these shopping malls are large buildings with over a hundred stores of all different brands. Inside the building everything is so well organized that there is the ultimate shopping climate. The mall is well air-conditioned, the lights are carefully regulated, there are bright colored and flashing advertisements everywhere and there is even a possibility to snack. Once a customer parks on the large parking lot, just outside one of the many entrances, they have no reason to leave, since everything they want is inside the shopping mall. There are thousands of products to choose from and one seems to be completely different from another. It is almost like an ultimate consumption paradise, because everything is carefully presented and available for consumption.

WORKING ON CONSUMERISM: SHOPPING MALLS AS THE MODERN IDEOLOGICAL WORKPLACE OF CONSUMERISM, PIRMIN OLDE WEGHUIS (2012)

Some malls are designed with a festive atmosphere first and foremost. In many places, e.g. Chile, these are called festival malls:

Also known as festival marketplaces, festival malls are commercial centers that combine special physical settings with social activities, leisure, and the consumption of goods and experiences, around a carnivalesque or festive specularization that has usually been addressed as iconic of the simulacra that characterize the consumption society.

Festival Malls, R. Liliana De Simone

If something is ‘carnivalesque’ (whether we’re talking about religious events, children’s picture books or… malls) that means hierarchy is temporarily overturned, and the entire purpose is for everyone to have fun for a while before returning to their normal, restricted lives. They started popping up in the 1970s and were first described as ‘shopping centers for the urban community’. They are part of what Peter Hall called ‘rousification’ after an urban planner and real estate developer called James W. Rouse.

Rousification: concerted efforts to recover historical landmarks by adapting an original marketplace formula. The investment model is a blend of public-private. Rousification changed the function of central business districts, from production to consumption.

Famous Festival Malls:

- Faneuil Hall (Boston, USA)

- Harborplace (Baltimore, USA)

- Plaza Mexico (Los Angeles, USA)

- The Grove at Farmers Market (Los Angeles, USA)

- Covent Garden (London, UK)

- Puerto Madero (Buenos Aires, Argentina)

- Punta Carretas (Montevideo, Uruguay)

How do you know you’re in a Festival Mall?

- You’ll find specialty goods and services usually tenanted by indie retailers (rather than chain stores)

- They’re all about spectacle. Each time you visit, something different will be on display.

- Artworks and local handicrafts will make this mall different from any other.

- These malls have local identity.

- They aim to attract tourists who would like a more local experience, as well as locals themselves (perhaps all the way from the suburbs, who take pride in their city.

Critics of festival malls point out that these retail spaces tend to exploit historic preservation laws. A mall is still a mall, a behemoth of a thing which usurps subsidised schemes designed to help truly independent retailers. In poorer countries, festival malls provide an experience for tourists visiting from wealthy countries. These tourists may feel safe and comfortable at a mall made specifically for them, and go back home thinking they’ve experienced local culture when they’ve done no such thing. For all their local colour, some festival malls exist to capture only the tourist dollar. Some even employ young, unskilled locals to act performatively as ‘authentic’ exhibits. This is a form of colonisation.

THE MALL AS POST-APOCALYPTIC EERIE UNCANNY

The Walking Dead and Survivors hint most prominently at the disturbed character of seemingly everyday habits and their implications for practices of consumption. The representation of empty consumerist places in post-apocalyptic narratives renders these places not only eerie but also ambivalent, as it challenges their supposedly primary function. While in everyday life the absence of people and empty cash desks in a supermarket may at least come in handy or represent a ‘pleasurable daydream of what a viewer might do should they find themselves free-range in their local mall’, in apocalyptic movies and series the absence of people leads to a feeling of unease and explores the logic of public and private places. In a world where resources are rare and people scavenge for food, a supermarket seems to offer a safe haven of supplies and allows the characters to embrace the familiar surroundings of commodity culture.

In the British zombie film 28 Days Later the protagonists discover an empty supermarket and indulge in an extensive shopping tour, like children in a toy store, and also digress from class-related buying behaviour. When the protagonist, Jim, a bicycle courier, stands by the drinks counter, picking up a bottle of cheap whiskey, the cab driver Frank responds: ‘Put that back. We can’t just take any crap’. Instead, he takes a bottle of Lagavulin and reads off the advertising text from the label: ‘Single malt. Sixteen years old. Dark, full flavour. Warm, but not aggressive. Pretty aftertaste’. Despite its comic effect, the emptiness of the place repeatedly serves as a reminder that under the rules of the apocalypse their seemingly ‘normal’ habit is a relic of the past. What is more, the empty supermarket’s full shelves — in a reverse fashion — also briefly explore a kind of utopian fantasy of freedom that consumer culture is able to supply — provided one has the financial means.

Landscapes of loss: the semantics of empty spaces in contemporary post-apocalyptic fiction by Martin Walter, from the book Empty Spaces: Perspectives on emptiness in modern history, 2019

In post-apocalyptic stories, the supermarket is often a site where survivors fight over resources, which of course is allegory for income inequalities in the realworld.

MALL AS METONYM FOR SUBURBIA

In stories set in the American suburbs the characters often make a trip to the mall. Mall trips emphasise the ‘suburban-ness’ of the setting.

Enclosed shopping malls mimic the downtown experience, which saves suburban residents from ever taking a trip downtown.

In Steven Millhauser’s “Miracle Polish” the mall gets a brief mention, but is almost a mandatory inclusion in a story about consumerism. A suburban mall is the ultimate symbol of modern consumerism more generally.

One night after dinner I drove to the outskirts of town, where the old shopping center faced off against the new mall in a battle of slashed prices. In the aisle after blenders and juicers I came to them. I saw tall narrow mirrors, square mirrors framed in oak and dark walnut, round mirrors like gigantic eyeglass lenses, cheval mirrors, mirrors framed in coppered bronze, mirrors with rows of hooks along the bottom.

“Miracle Polish”

See also “Cosmopolitan” for a short story example of the American mall utilised for storytelling in this way.

THE MALL AS UNSUPERVISED PLAY VENUE FOR ADOLESCENTS

Malls are increasingly becoming centres where not only can an individual make several kinds of purchases at once, but also watch films, eat food, socialise, or just “hang out”. They are a sort of microcosm of urban life, where all that makes the urban modern and unique are present. Also, these spaces are strategically located and designed in order to attract consumers.

Constantly Watched: Shopping Malls as Heterotopia and Panopticon, Srishti Raj

From Pretty Little Liars to Mean Girls, the shopping mall features large in many suburban tales for teens. The mall is frequently the first place teenagers are allowed to roam unsupervised.

It’s amazing how many of these stories feature a character who shoplifts. I guess what’s amazing is, shoplifting is so frequently used as a moral shortcoming to engender empathy from the young audience, meaning, we are supposed to like them because they steal stuff.

Shoplifting is a highly gendered trope: It’s most often girls and women stealing a particular kind of item. Can you guess what that is? Fashion items and make-up.

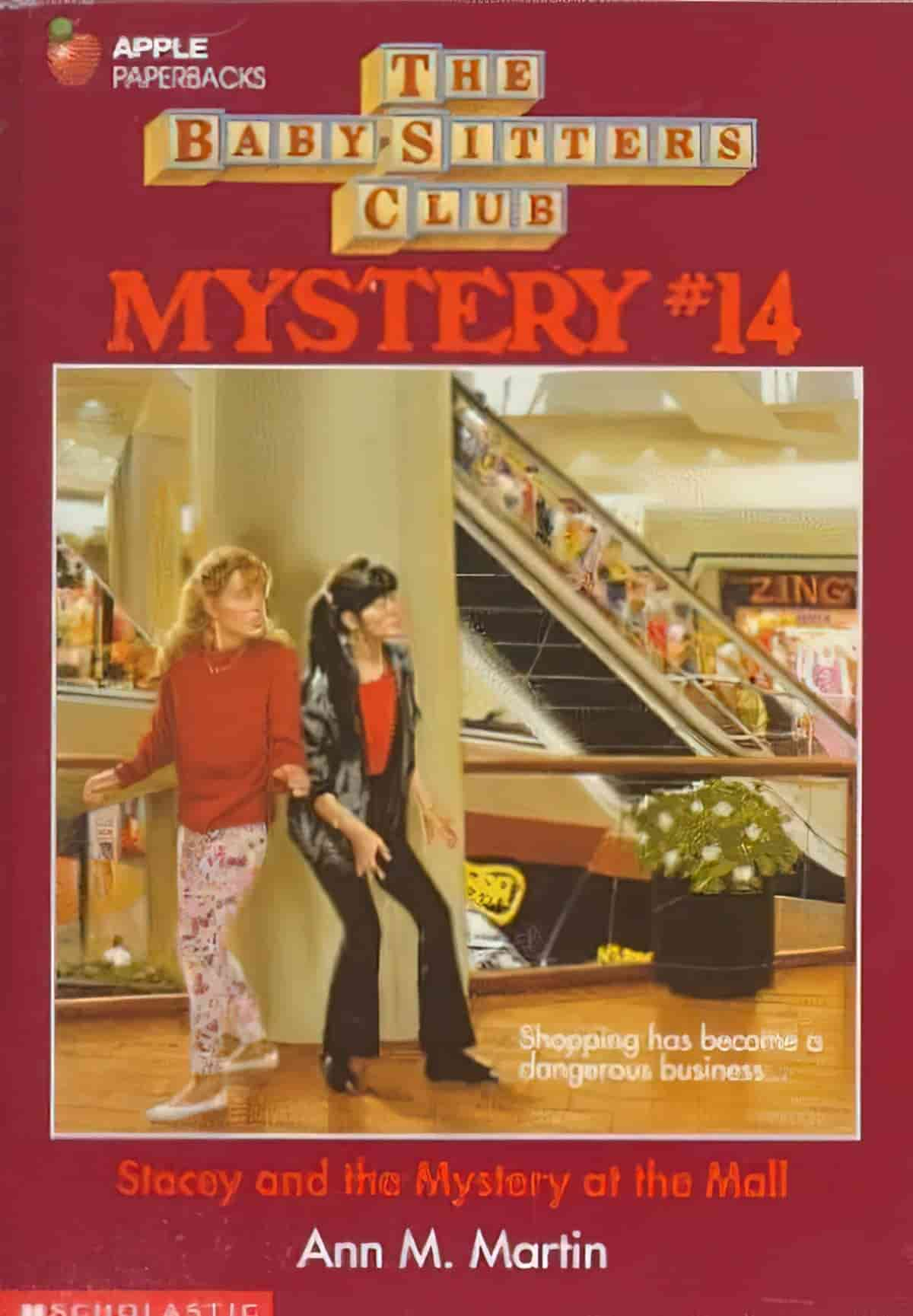

Stacey and the Mystery At The Mall Babysitters Club Ann M. Martin (1994)

The Baby-sitters are all taking a class at SMS where they are assigned jobs at the Washington Mall. How cool – going to “school” at the mall!

But soon Stacey learns that some pretty bad things are going on there. Besides the regular shoplifting problems, expensive things are being stolen, too. and then Stacey has a big scare when she’s working at Toy Town.

Is it safe to shop at Washington Mall anymore? The Baby-sitters aren’t sure – but they’re going to make sure this mystery is solved!

THE MALL AS HORROR VENUE

If it’s banal and everyday and American, Stephen King has turned it into horror. The standout example: The Mist, which is not a mall in his original short story, nor in the first film adaptation. However, the most recent adaptation (a TV series) now takes place in a mall.

The general store/shopping mall is a place of refuge, functioning as a symbolic island for shipwrecked sailors. In the store the characters of The Mist have everything they need* for survival (at least for a while), but the threat from outside just won’t quit. The ironic juxtaposition: Setting becomes a haven with endless supplies, but is also a cage. Personalities will clash, and ultimately come from within.

‘Need’ is an interesting concept when it comes to consumerism, because people buy many things not because those things are needed for survival, but because of what they signal to others. Malls are about relationships, ultimately. If this weren’t the case, malls wouldn’t be such excellent horror venues, because people could simply bunker down and survive on canned goods until the army rocks up.

The real value and the symbolic value of commodities are completely separated from another and in a shopping mall this disappearance of reality into simulation is complete. Since there are no ‘needs’ that really have to be fulfilled in order to survive people start buying commodities they do not actually need in that same sense. Everything around them, material, social and political has become a commodity with sign value. In the shopping mall several of the aspects of this simulation of everything are clearly visible.

WORKING ON CONSUMERISM: SHOPPING MALLS AS THE MODERN IDEOLOGICAL WORKPLACE OF CONSUMERISM, PIRMIN OLDE WEGHUIS (2012)

THE MALL IS A MODERN-DAY LABYRINTH

The labyrinth is heavy with symbolism, thanks to the Ancient Greeks. Venture too far in and you’ll find a Minotaur at the centre. The labyrinth, like the mall, sucks you in. You have trouble finding your way out.

This is by design.

The Gruen Effect is a podcast from 99% Invisible and explains the phenomenon whereby a shopper goes to buy something specific, but once bombarded with all a shop has to offer, forgets what they came for. This is ideal, if you’re trying to sell stuff.

In the second film of the Living Dead series (Dawn of the Dead) the story also takes place (mostly) in an abandoned shopping mall. This mall is packed with zombies who mindlessly shuffle, push and shove around the labyrinthine space. They groan and grunt and mindlessly attack anything they think might be edible flesh. Dawn of the Dead is a commentary on mindless consumerism, and uses zombies.

It’s not just the layout of a shopping mall which keeps us inside the precinct for as long as possible. It’s the endless cycle of consumerism, which under capitalism, keeps consumers wanting more and more:

through stimulating individuality they keep creating consumer’s ‘needs, ’since this individuality stimulates differentiation. Differentiation will never end, because it can never be satisfied by mere consumption of one specific product. After a consumer consumed one product the ‘need’ for another is instantly created.10Thus the mall, with all the sign value products and advertisements, is ensuring the continuation of the system. It stimulates people to consume the system of consumption.

WORKING ON CONSUMERISM: SHOPPING MALLS AS THE MODERN IDEOLOGICAL WORKPLACE OF CONSUMERISM, PIRMIN OLDE WEGHUIS (2012)

MALL AS PRISON

If you can’t easily get out of a labyrinth, you can’t get out of a prison.

The following description doesn’t map neatly onto all countries (such as here in Australia), though mall security is constantly vigilant:

To enter a shopping mall, an individual must fulfil certain criteria. One of the most overt ways of limiting admission is at the very entry of the building, i.e. security. Shopping malls have several layers of security measures, in order to prevent terrorist attacks and theft. Cars entering the compound are stopped, checked (both by hand-held scanners and manual inspection of the undercarriage and the trunk), identified, and then sent to the parking area. Individuals then have to subject their bodies to examination, by a metal detector and a security guard. Their belongings, too, are either rifled through by these guards or passed through a machine that uses x-rays to reveal the contents of their bags.

Constantly Watched: Shopping Malls as Heterotopia and Panopticon, Srishti Raj

Michel Foucoult called this ‘hierarchal observation’ and wrote about the concept of the panopticon. Malls are fitted out with security cameras everywhere. Security are keeping an eye on potential consumers as well as on staff.

Punta Carretas Shopping center in Uruguay is literally a former prison. It housed the tupumaros guerrilleros in the 1970s, but the prisoners escaped. After that, it was decided the building would work better as a mall.

SHOPPING MALLS AS SYMBOLS OF THE DEADLY SINS

If looked at from an extremely critical, judgemental eye, framed by traditional notions of religious morality, shopping malls are guilty of being dens for at least five of the seven deadly sins — envy, lust, greed, gluttony, and sloth. They are places where greed and consumption are acts that are acceptable and even encouraged, with individuals constantly being told through advertisements that spending more and more money, on more and more consumer goods and services, will make their lives better. They are motivated to improve themselves through advertisements that use sex and desirability, attributes that other people, better than them, already possess. They are also spaces of idleness (malls are places where one can ‘kill time’ or ‘hangout’), generally frowned upon by society, which values leisure (as a reward for hard work) over laziness.

Constantly Watched: Shopping Malls as Heterotopia and Panopticon, Srishti Raj

Contemporary audiences are increasingly cognizant of the problems with malls, and the consumerism and the environmental destruction. Storytellers can now easily create fictional consumers as victims in a horror plot which punishes ‘deserving’ sinners.

SHOPPING MALLS AND ZOMBIES

Zombies mean all sorts of things in stories, depending on what the author wants to say. They frequently indicate contagion. Zombies are also useful when making a statement about mindless consumerism.

The mall is a modern-day battleground, not for our lives per se, but for our place in the social hierarchy:

Principles of equality have caused the end of the old aristocracy, which has led to a society in which one is defined through consumption. With traditional differences in status or class fading people needed a new way to affirm their personality or status. In large groups the need for differentiation grows rapidly, but these ‘needs’ grow “not from the growth of appetite, but from competition.”

WORKING ON CONSUMERISM: SHOPPING MALLS AS THE MODERN IDEOLOGICAL WORKPLACE OF CONSUMERISM, PIRMIN OLDE WEGHUIS (2012)

Another feature of zombies: zombification turns individuals into the same monster. Malls also do this:

The choice a consumer makes is not relevant to the system as such, but it is relevant to the system that the consumer keeps making a choice. Individual ‘needs’ of consumer s are not real needs, but rather they are determined by the system.9The system, through the shopping mall, has to put focus on the individuality of consumers.

WORKING ON CONSUMERISM: SHOPPING MALLS AS THE MODERN IDEOLOGICAL WORKPLACE OF CONSUMERISM, PIRMIN OLDE WEGHUIS (2012)

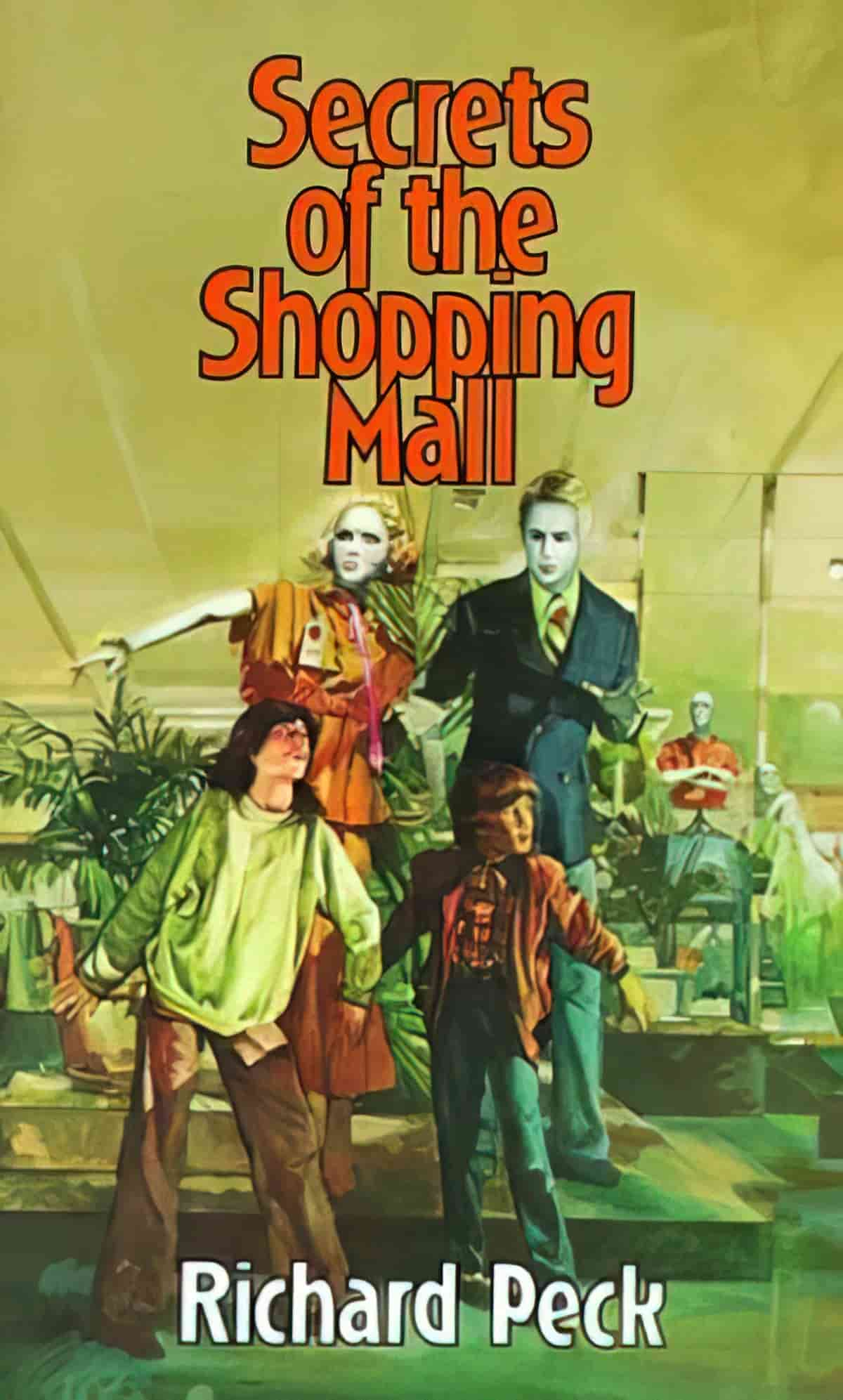

Richard Peck was an American children’s writer who created some of my favourite stories of all time. (A Long Way From Chicago is wonderful.) However, Peck also wrote books which don’t travel so well into the 21st century. One of those is Secrets of the Shopping Mall (1978).

As you can see from this cover, mannequins are part of the horror symbolism, and are inherently zombie-like. (The fact that mannequins exist lends malls very well to zombie tropes.)

Trying to escape the vicious King Kobra gang and a troubled life at home, eighth graders Barnie and Teresa flee the city. With only four dollars between them, they hop a bus, hoping to find a new life at the end of the line. Destination: Paradise Park. But Paradise Park turns out to be a cement-covered suburban shopping mall–not quite the paradise they had hoped for.

With no money and no home to retum to, they are forced to stay. And paradise park takes them in–in more ways than one. Barnie and Teresa spend their days and nights in the climate-controlled consumer paradise of a large department store. And just when they think they can live there unnoticed forever, Teresa and Barnie find that even Paradise Park has its secrets. Even in the dead of night, they are far from alone….

The hosts at the Teen Creeps podcast analysed Peck’s story of bullying in 2022 and had this to say about it:

- Perhaps kids grow up faster these days, but what was a ‘young adult’ novel in the late seventies now reads like something pitched at about the horror level of an eight-year-old.

- That said, readers vary widely in their tolerance for animal cruelty, and all cat lovers will be horrified at the scene where a cat is swung around by its tail. (The cat would surely die from such abuse. Modern audiences are far more aware of what constitutes abuse in animals. (Some early 20th century books for children are horrifying for their unwitting cruelty.)

- Cats and malls seem to go together, though.

- There’s a Lord of the Flies vibe to this story (which isn’t surprising, given that shopping malls serve as islands in stories structured as a Robinsonnade myth.)

- The ideology of Peck’s Secrets of the Shopping Mall calls to mind late 1970s proto-Reganomics.

- In the end, the children are saved because the mall becomes their home. They find entry level jobs and now their entire lives revolve around the mall. They live there as well as work there, and this is presented as a happy ending.

- Unfortunately, this means Peck’s story subscribes to what many now recognise as The Lie of Capitalism: Start with an entry level job and work your way up. This is a lie because there are many entry level jobs and very few opportunities for advancement. No matter how hard people work, the vast majority will remain in entry level jobs. However, the remote possibility of advancement keeps people working hard for The Man. The hosts compare this aspect to Dangerous Minds. (I would compare it to Gilmore girls, in which Lorelai gets pregnant at sixteen, finds an entry level job at a hotel, and by her early thirties has worked her way up to management position via sheer hard work, apparently, though we never see her do any cleaning.)

THE MALL AS EVERYONE’S WORKPLACE

While Richard Peck didn’t critique the existence of mall as endless workplace, others have:

The shopping mall should be viewed as a kind of a modern working place. In the mall people, through their ‘need’ based choices, reinforce the system of consumption. Only because people are in the shopping mall, all together with all the different products, value is created in those products. The consumer is thus “required and mobilized as worker at this level too” and this task is as important as their actual production work.12Theshopping mall serves as the ideal ideological working place, because is encompasses all the essential points of consumerism. The example of Black Friday again signifies how the process works, because people are drawn to the department store by advertisement and once inside the great spectacle of all the different brands begins. It is the most alluring way of creating consumers, because the mall invites people to consume.

WORKING ON CONSUMERISM: SHOPPING MALLS AS THE MODERN IDEOLOGICAL WORKPLACE OF CONSUMERISM, PIRMIN OLDE WEGHUIS (2012)

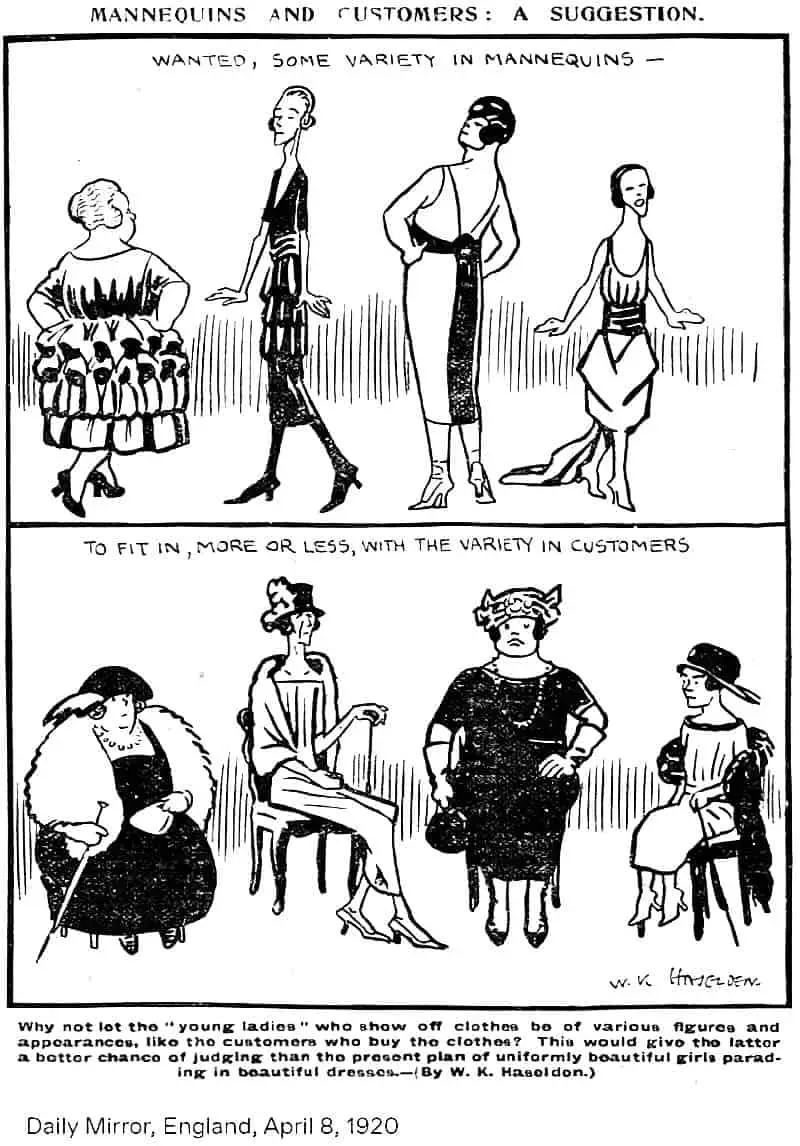

THOSE CREEPY MANNEQUINS

Mannequins have changed a lot since I was a kid. The mannequins at our local shopping centre look more like aliens than people, which has a strange effect: This actually takes them out of uncanny valley.

Mannequin Pixie Dream Girl is a podcast about window displays in department stores from 99% Invisible

THE MALL AS PLACE OF CAPTIVITY

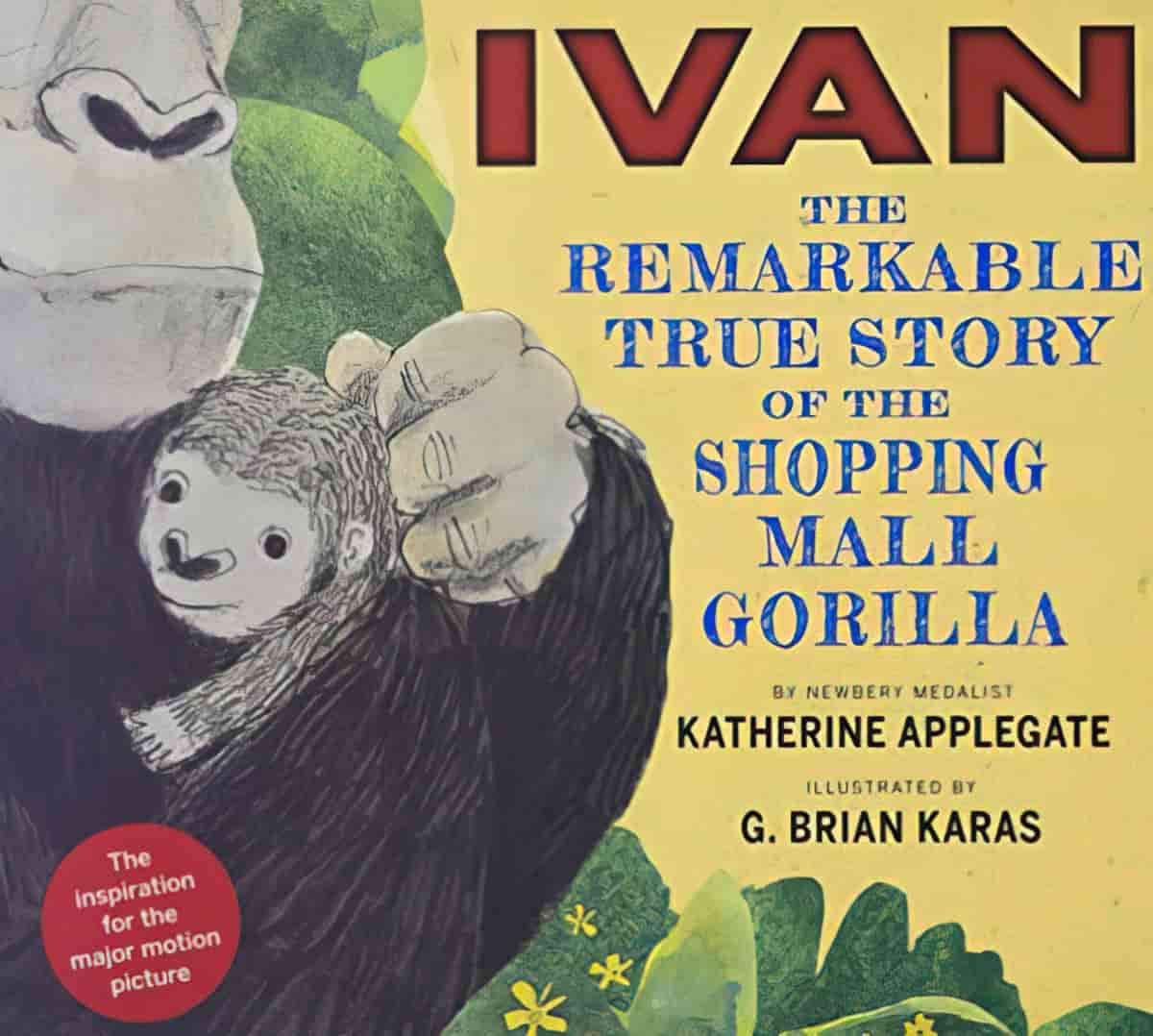

Ivan: The Remarkable True Story of the Shopping Mall Gorilla by Katherine Applegate (2004)

In a spare, powerful text and evocative illustrations, the Newbery medalist Katherine Applegate and the artist G. Brian Karas present the extraordinary real story of a special gorilla.

Captured as a baby, Ivan was brought to a Tacoma, Washington, mall to attract shoppers. Gradually, public pressure built until a better way of life for Ivan was found at Zoo Atlanta. From the Congo to America, and from a local business attraction to a national symbol of animal welfare, Ivan the Shopping Mall Gorilla traveled an astonishing distance in miles and in impact.

When animals are brought into shopping malls as drawcards for families, they are now, effectively, zoos.

Whereas 20th century children’s books frequently depicted zoos as utopian spaces for children and families, this started to change around the 1960s, when authors began critiquing the idea that wild animals belong behind bars. See, for instance, Veronica by Roger Duvoisin. Anthony Browne created the ultimate anti-zoo picture book in the 1990s.

IN THE MALL TIME WORKS DIFFERENTLY

The stores are a lot of the time almost twenty-four hours a day opened, but inside one is not aware of the time of the day. While inside the building people experience and live in a “perpetual present.” This perpetual present together with all the signs without signifiers, since both the original and the use value are gone, create a reality in which everything is possible. Everything can be materialized, made a commodity, for customers to buy.

WORKING ON CONSUMERISM: SHOPPING MALLS AS THE MODERN IDEOLOGICAL WORKPLACE OF CONSUMERISM, PIRMIN OLDE WEGHUIS (2012)

Where else does time work differently? In fairy tales. Inside a mall, time no longer feels linear, so entry to the mall marks a shift from chronos to kairos.

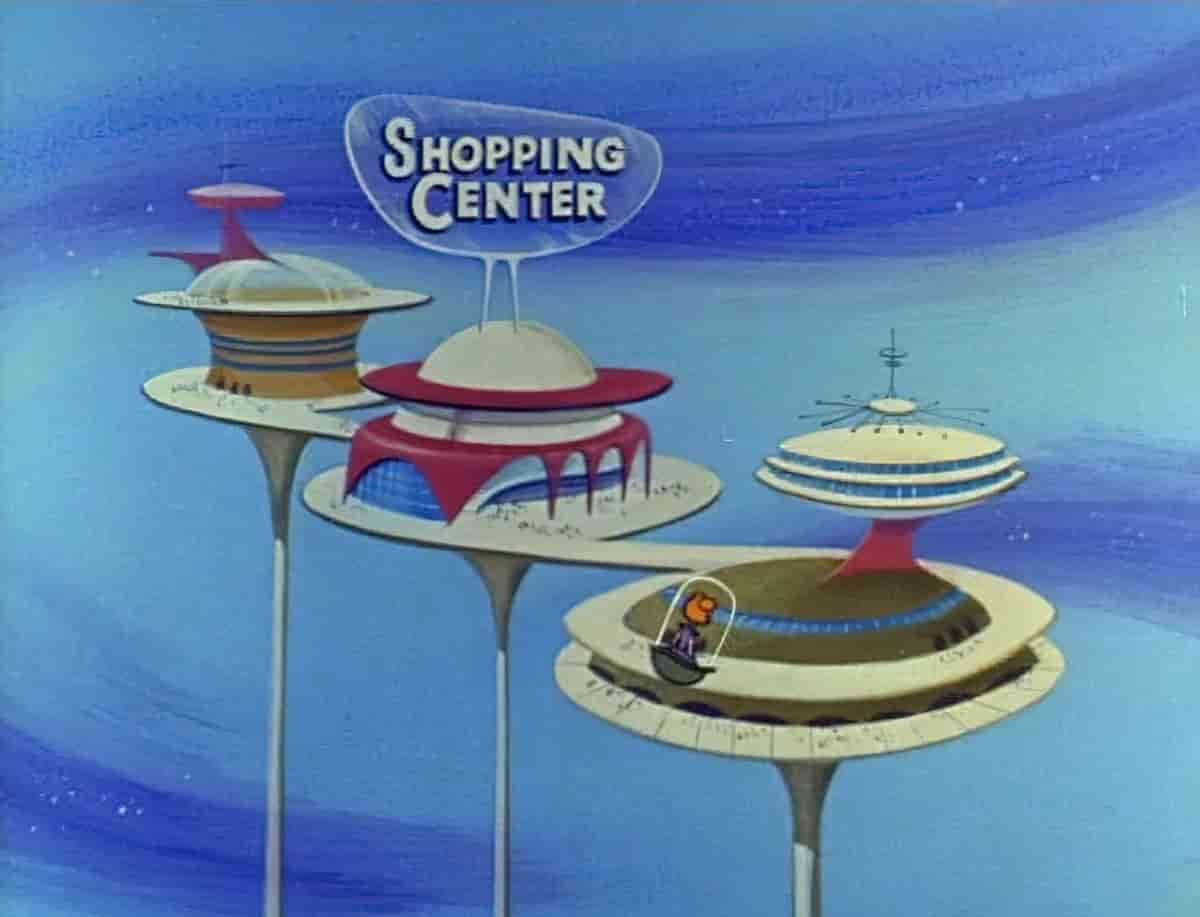

THE MALL AS FUTURISTIC SHOWCASE

We typically associate kairos with primitive society, but malls are, ironically, also attempts at transporting us to an idealised, better future. Wherever they can, mall management spend a lot of money refurbishing their premises, updating décor before it has technically worn out. Obviously, retailers want consumers to spend as long as possible at the mall, buying all of the things.

MALL AS GATED COMMUNITY

At the same time, the mall is not homely. (See above: Mall as Prison.) The mall is a gated community which will employ security guards to remove unhoused people who linger in its ‘avenue’.

The shopping mall has been called a ‘pseudo-public’ space. (One of the first to introduce this notion was Mike Davis.)

Shopping malls require their customers to be affluent in order to make a profit. Those who do not fall into this category are rejected from entering not only due to their inability to spend money, but in order to appease the higher classes for whom such individuals are undesirable. The only way for someone from a lower class to enter a mall is as an employee engaged in menial tasks such as janitorial work, food preparation, delivery, maintenance, etc. Even then, they are issued a uniform so as to distinguish them as employees and not people who have also come to spend their time in the mall as consumers.

Constantly Watched: Shopping Malls as Heterotopia and Panopticon, Srishti Raj

The mall is a simulation of an idealised future, in which poverty is solved. We can all have exactly what we want, as soon as we want it. Even little kids can become adults with agency by scooting around in the tiny cars with flags on them. Santa appears at Christmas to push the consumerist message onto the next generation. Ask and you shall receive.

The mall Santa is not ‘fake’; he is part of the much broader simulation, which is very real in its consequences.

MALL AS HETEROTOPIA

What’s a heterotopia, you ask?

Now, what makes a mall an excellent example of heterotopia (rather than like any ordinary public place)? Malls are not accessible to everyone. People can be denied entry or removed by security.

First, there’s the fact that time works differently in malls. Foucault calls these places ‘heterochronies’.

Also, people behave differently inside shopping malls. We are all turned into flaneurs. The social rules change. This is another feature of a heterotopia: These places have their own rules. (In fact, this is the first principle of heterotopology.) Outside a mall we’d feel ashamed to succumb to our lust, envy, greed, gluttony and sloth. But the environment of a mall supports such individualistic behaviours. Once entering through the portal, we are not supposed to care about what’s happening to other people in the outside world. (The entranceways to malls are frequently remarkable, signalling the shift to an other world.)

Another feature of heterotopias which apply very much to malls: The admixture of very different things. You can eat a hamburger and also go to the gym. You can watch a movie and then get new glasses.

Shopping malls are simulations rather than ‘real’: Everything about malls takes us away from the messiness of our main lives. Models on billboards are either happy or sultry. Retail staff are required to be constantly chirpy and helpful, and to dress well. The climate is controlled, there is no messiness on display and no signs of inequality and poverty.

Another, similar word for a shopping mall: ‘non-place’. This term was coined by Marc Augé.

transit and anonymous spaces that allow the fast flow of a larger number of individuals. Since they are deprived of identity, history and meaning as a social construct, non-spaces are not anthropological places. With transition of functions primarily intended for an open public space, to pseudo premises of the malls, purpose of the city square is lost. The streets and the squares of the shopping mall have been designed to create the impression that they are public spaces. However, it is a privately-owned space with movement restrictions and controlled behaviour of consumers, with selective access and video surveillance

SHOPPING MALL VS. OPEN PUBLIC SPACE IN CONSUMER CULTURE, Aleksandra Djukic, Marija Cvetkovic

FURTHER READING

Predators use American shopping malls and other places where young, teenage girls may not have adult supervision in order to find their victims for sex trafficking. (See this article, for instance.)

FURTHER STORIES ABOUT MALLS

Heaven Looks A Lot Like The Mall by Wendy Mass (2007)

When 16-year-old Tessa suffers a shocking accident in gym class, she finds herself in heaven (or what she thinks is heaven), which happens to bear a striking resemblance to her hometown mall. In the tradition of It’s a Wonderful Life and The Christmas Carol, Tessa starts reliving her life up until that moment. She sees some things she’d rather forget, learns some things about herself she’d rather not know, and ultimately must find the answer to one burning question—if only she knew what the question was.

I Woke Up Dead At The Mall by Judy Sheehan (2016)

Do you know which book started the dead narrator trend? Yep, The Lovely Bones. As usual, the trend started in YAL and made its way up to books for adults.

When Sarah wakes up dead at the Mall of America, she learns that not only was she murdered, her killer is still on the loose.

When you’re sixteen, you have your whole life ahead of you. Unless you’re Sarah. Not to give anything away, but . . . she’s dead. Murdered, in fact. Sarah’s murder is shocking because she couldn’t be any more average. No enemies. No risky behavior. She’s just the girl on the sidelines.

It looks like her afterlife, on the other hand, will be pretty exciting. Sarah has woken up dead at the Mall of America—where the universe sends teens who are murdered—and with the help of her death coach, she must learn to move on or she could meet a fate totally worse than death: becoming a mall walker.

As she tries to finish her unfinished business alongside her fellow dead teens, Sarah falls hard for a cute boy named Nick. And she discovers an uncanny ability to haunt the living. While she has no idea who killed her, or why, someone she loves is in grave danger. Sarah can’t lose focus or she’ll be doomed to relive her final moments again and again forever. But can she live with herself if she doesn’t make her death matter?

The Mall: A Novel by Megan McCaffeerty (2020)

The year is 1991. Scrunchies, mixtapes and 90210 are, like, totally fresh. Cassie Worthy is psyched to spend the summer after graduation working at the Parkway Center Mall. In six weeks, she and her boyfriend head off to college in NYC to fulfill The Plan: higher education and happily ever after.

But you know what they say about the best laid plans…

Set entirely in a classic “monument to consumerism,” the novel follows Cassie as she finds friendship, love, and ultimately herself, in the most unexpected of places. Megan McCafferty, beloved New York Times bestselling author of the Jessica Darling series, takes readers on an epic trip back in time to The Mall.

Ewan Morrison’s top 10 books about shopping malls from The Guardian

FURTHER READING

The Invention of Public Space: Designing for Inclusion in Lindsay’s New York

As suburbanization, racial conflict, and the consequences of urban renewal threatened New York City with “urban crisis,” the administration of Mayor John V. Lindsay (1966–1973) experimented with a broad array of projects in open spaces to affirm the value of city life. Mariana Mogilevich provides a fascinating history of a watershed moment when designers, government administrators, and residents sought to remake the city in the image of a diverse, free, and democratic society.

New pedestrian malls, residential plazas, playgrounds in vacant lots, and parks on postindustrial waterfronts promised everyday spaces for play, social interaction, and participation in the life of the city. Whereas designers had long created urban spaces for a broad amorphous public, Mogilevich demonstrates how political pressures and the influence of the psychological sciences led them to a new conception of public space that included diverse publics and encouraged individual flourishing.

Drawing on extensive archival research, site work, interviews, and the analysis of film and photographs, The Invention of Public Space: Designing for Inclusion in Lindsay’s New York (University of Minnesota Press) considers familiar figures, such as William H. Whyte and Jane Jacobs, in a new light and foregrounds the important work of landscape architects Paul Friedberg and Lawrence Halprin and the architects of New York City’s Urban Design Group.

The Invention of Public Space brings together psychology, politics, and design to uncover a critical moment of transformation in our understanding of city life and reveals the emergence of a concept of public space that remains today a powerful, if unrealized, aspiration.

interview at New Books Network

Vacant to Vibrant: Creating Successful Green Infrastructure Networks (Island Press, 2019)

Vacant lots, so often seen as neighborhood blight, have the potential to be a key element of community revitalization. As manufacturing cities reinvent themselves after decades of lost jobs and population, abundant vacant land resources and interest in green infrastructure are expanding opportunities for community and environmental resilience. Vacant to Vibrant: Creating Successful Green Infrastructure Networks (Island Press, 2019) explains how inexpensive green infrastructure projects can reduce stormwater runoff and pollution, and provide neighborhood amenities, especially in areas with little or no access to existing green space. Sandra Albro offers practical insights through her experience leading the five-year Vacant to Vibrant project, which piloted the creation of green infrastructure networks in Gary, Indiana; Cleveland, Ohio; and Buffalo, New York. Vacant to Vibrant provides a point of comparison among the three cities as they adapt old systems to new, green technology. An overview of the larger economic and social dynamics in play throughout the Rust Belt region establishes context for the promise of green infrastructure. Albro then offers lessons learned from the Vacant to Vibrant project, including planning, design, community engagement, implementation, and maintenance successes and challenges.

interview at New Books Network

Pedestrian Modern: Shopping and American Architecture, 1925-1956

Most of us have been to strip malls–lines of shops fronted by acres of parking–and most of us have been to closed malls–massive buildings full of shops and surrounded by acres of parking. Fewer of us have been to open malls: small parks ringed by shops with parking carefully tucked out of sight. That’s because open malls–once numerous–have largely disappeared, having been replaced by strip malls, closed malls and, more recently, big-box stores. As David Smiley points out in his wonderfully researched and beautifully illustrated book Pedestrian Modern: Shopping and American Architecture, 1925-1956 (University of Minnesota Press, 2013), the open mall was a response to a number of macro-historical, mid-twentieth century forces: the explosion of car culture, the decline of urban centers, the rise of suburbs, and, of course, mass consumerism. But he also shows that the open mall wasn’t just an banal machine for selling; it was a canvas upon which Modernist architects could create a uniquely American kind of Modernist architecture. The strip mall, the closed mall, and the big-box store may be artless, but the mid-century open mall certainly was not. It had style, as the many wonderful images in David’s book show. Interestingly, the open mall is making a comeback. I visited one outside Hartford, Connecticut. Alas, it has none of the Modernist elements that made the original open malls so interesting. To me, it looked like a closed mall turned inside out.

interview at New Books Network

Learn about the social and economic implications of the supermarket on this week’s episode of A Taste of the Past. Linda Pelaccio talks with University of Minnesota History Professor Dr. Tracey Deutsch about “building a housewives’ paradise.” Tune into this program to learn about the inception of the supermarket as an American institution in the 1930s. Find out how supermarkets aimed to appeal to women through their interior design, layout, and overall aesthetic. How did local food pricing regulations cause some grocery stores to fail, and others to thrive? Tune into this episode to learn how issues of gender, class, and race are tied up in the success of the American supermarket.

“The very first supermarkets did feature super low prices… They were hugely popular, but then many of them went out of business. If you cut your prices too low, you’re not going to be able to stay in business!” [11:10]

“Having predictable sales became more important to these larger stores.” [26:15]

— Dr. Tracey Deutsch on A Taste of the Past

Housewives’ Paradise: History of Supermarkets