Ships, boats and other sea vessels are symbolically significant across literature. How are they used and what do they symbolise?

The ship: ‘a living, micro-cultural, micro-political system in motion’

Paul Gilroy in “John Howison’s New Gothic Nationalism and Transatlantic Exchange”, Early American Literature

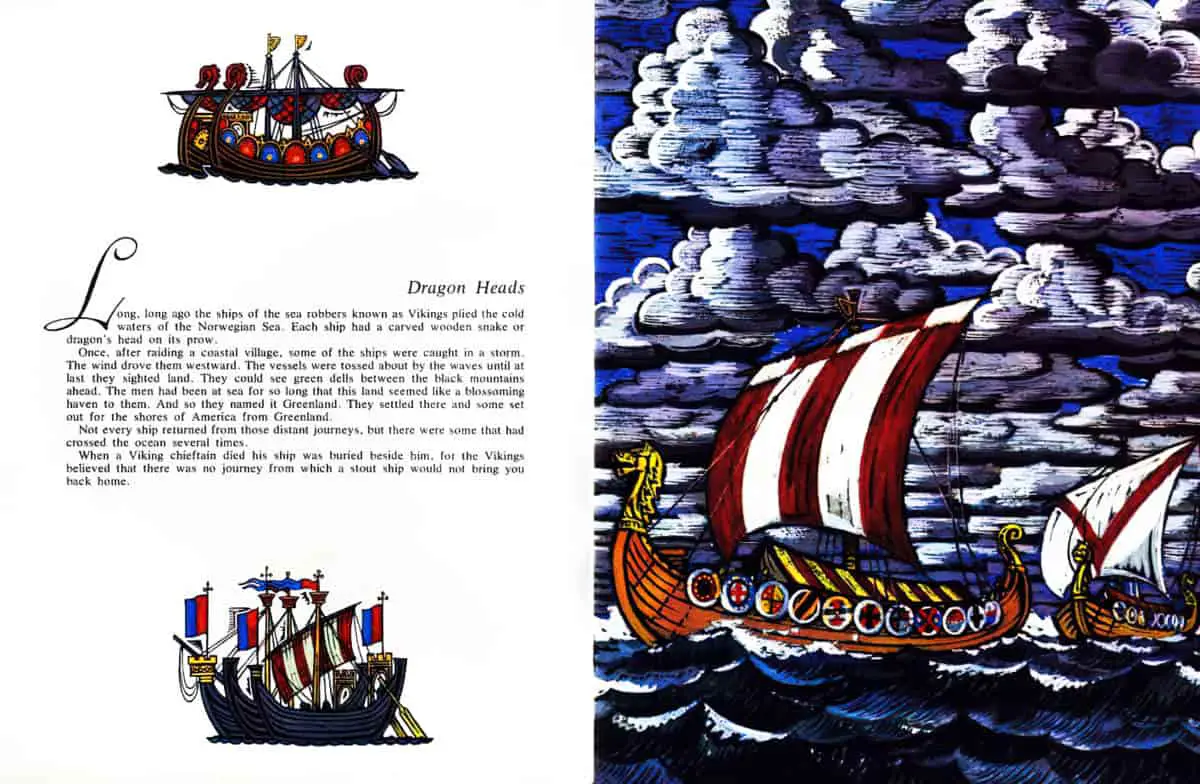

Ship stories are almost always mythic in structure and this includes stories of shipwrecks. In mythic stories, a character either goes on a journey (or stays in one place), meets a variety of allies and foes, has some kind of big revelation (Anagnorisis) then returns home (or finds a new one) as a changed person.

Both Gulliver and Robinson Crusoe eventually return home. Gulliver’s journey is Odyssean whereas Robinson Crusoe plonks himself in one place (perhaps on an island). Robinson Crusoe is such an iconic example of the ‘plonk yourself in once place’ adventure that we now refer to such stories as the Robinsonnade.

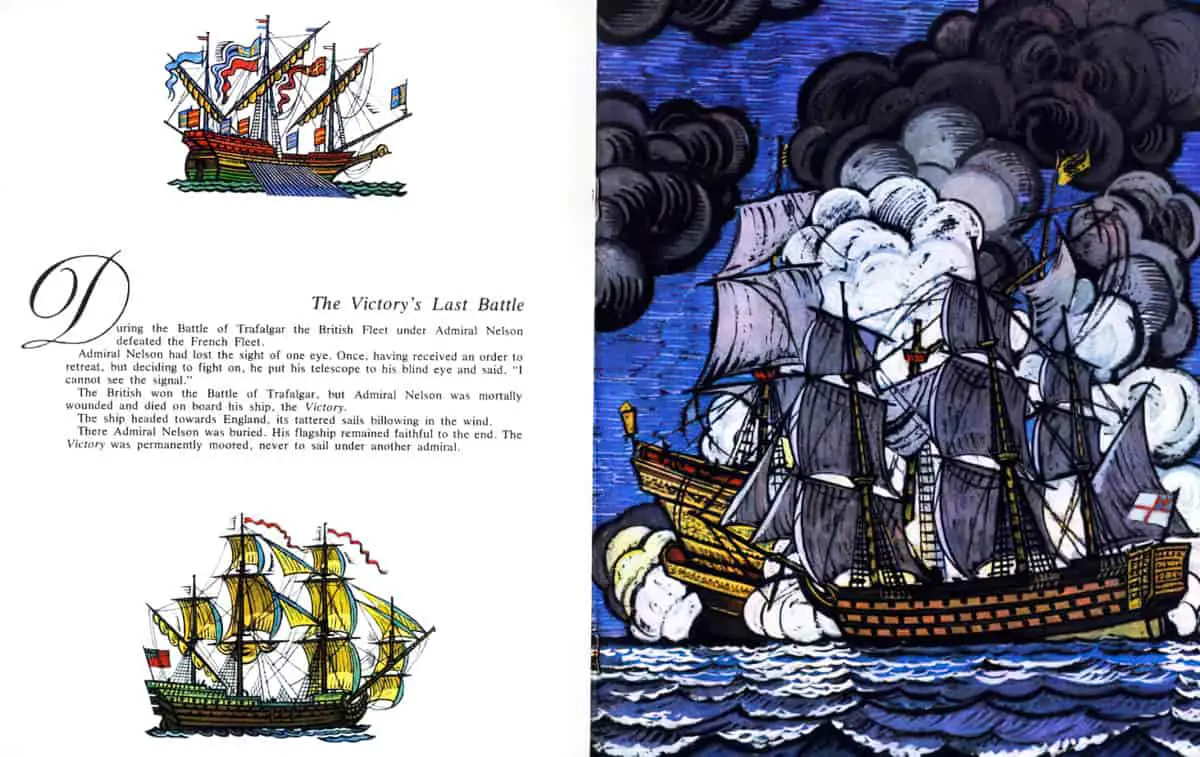

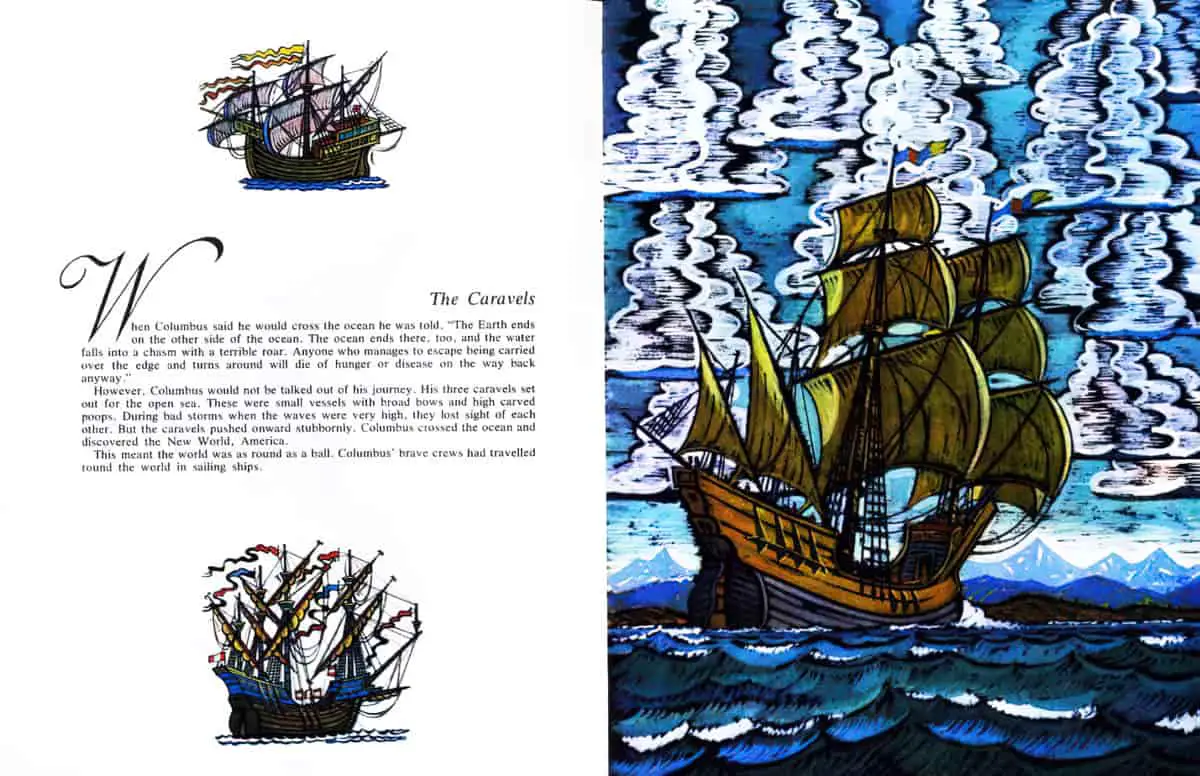

THE AGE OF SAIL

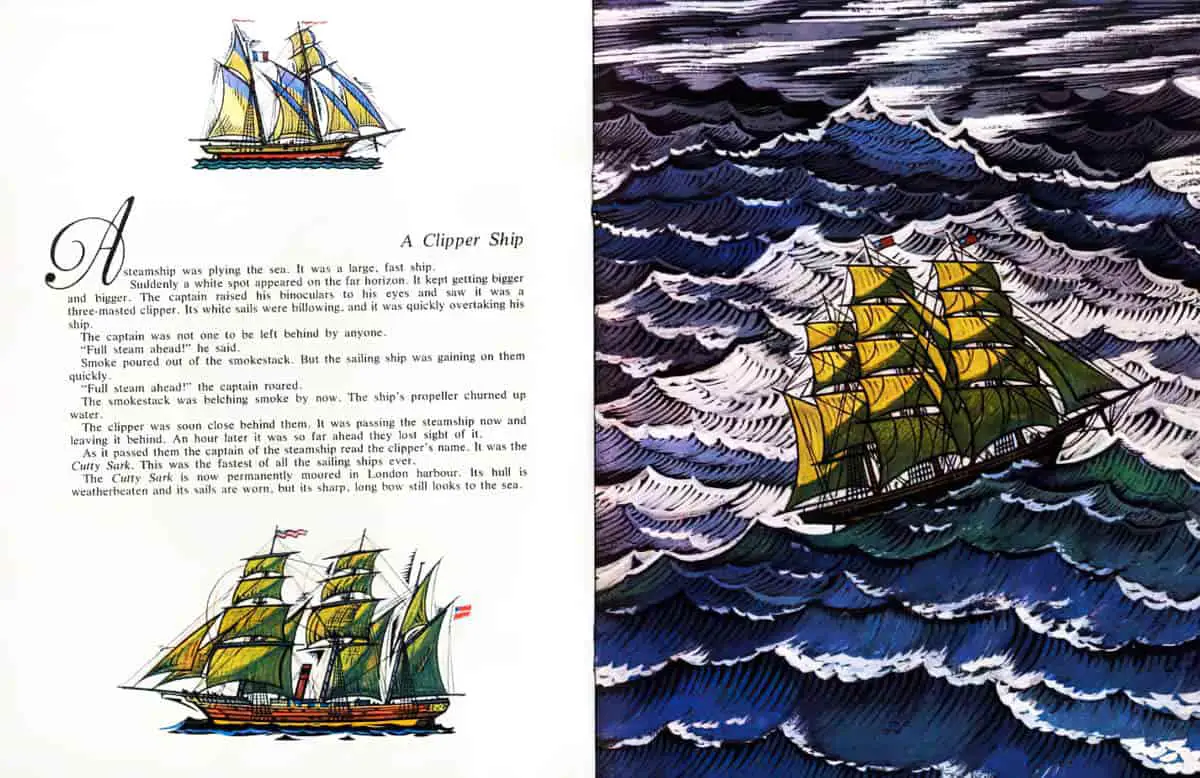

The Age of Sail lasted from the mid 15th century until the mid 19th century, depending on who you ask. Some say from the mid 16th century. Sailing ships are truly ancient inventions, but during the Age of Sail ships started to be used for warfare. Advances in navigation happened. Steam ships happened. Once steam ships happened, sailing ships were no longer needed. In the early 1870s HMS Devastation came along. This was the first battleship without sails. This marked the end of The Age of Sail.

The Golden Age of Sail is a similar phrase, and refers more specifically to that time between the mid 19th century and the early 20th century when sailing ships got about as big as they were ever going to get.

Before the twentieth century, sailing was far more dangerous than it is now. Some of this was to do with the inherent danger of the sea.

Common ways to die on a ship:

- Turbulent weather

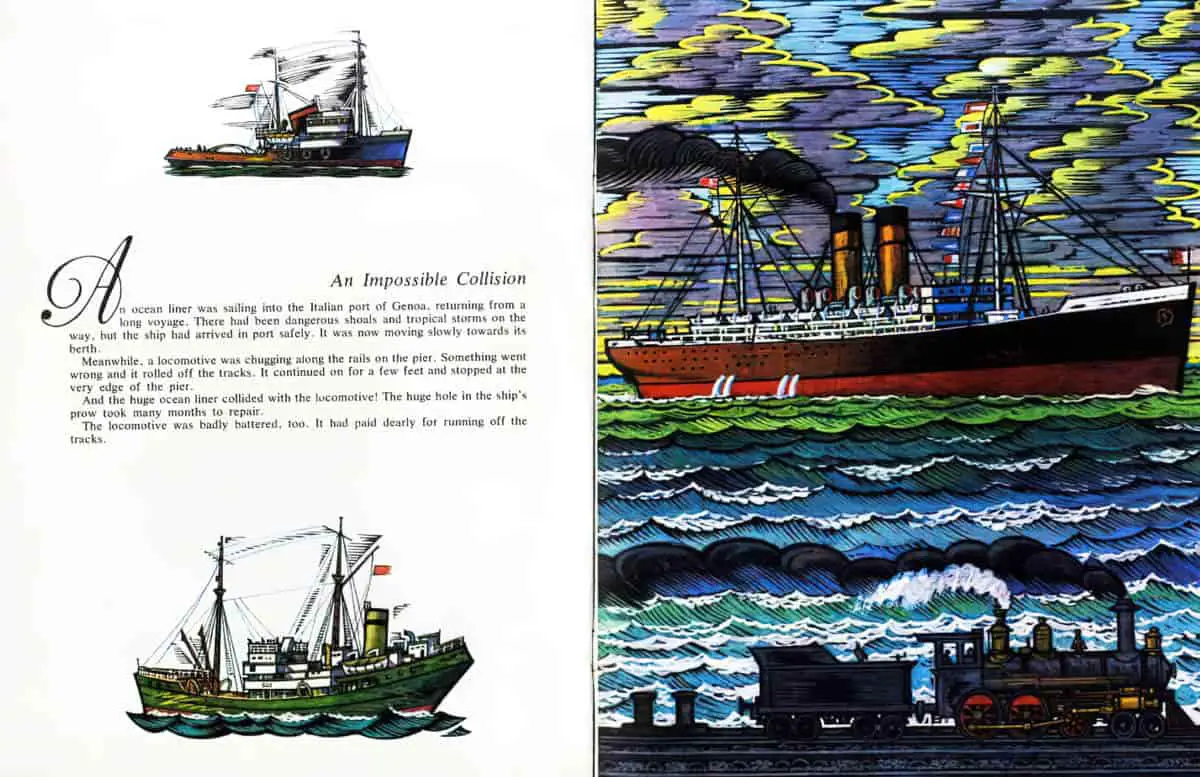

- Collision with another ship in one of the crowded estuaries

- Running aground because of navigation errors

- Fire to the waterline due to spontaneous ignition of flammable cargo

But sometimes sailors were deliberately killed by greedy and powerful humans. To collect on lucrative insurance, shipping companies regularly sent overloaded ships out to sea, manned, of course, intending for them to sink. Who’d dare get on such a ship? The sailors were often recruited from the streets. These were society’s ‘disposable’ people, sent off on a sure death mission.

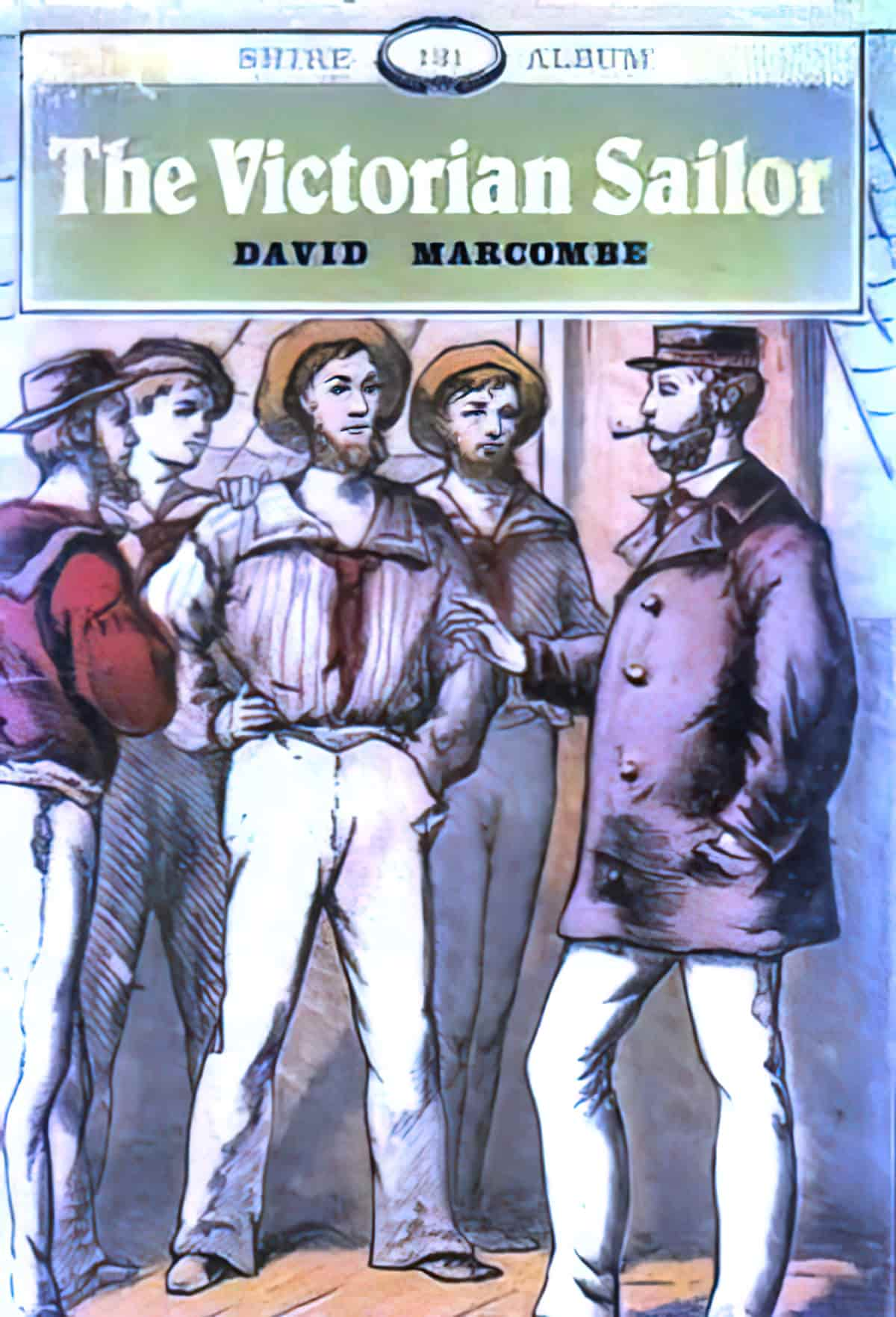

Between 1879 and 1899 alone, 11,000 British lives were lost at sea across 1153 missing ships. For more on that see David Marcombe, The Victorian Sailor, 1985.

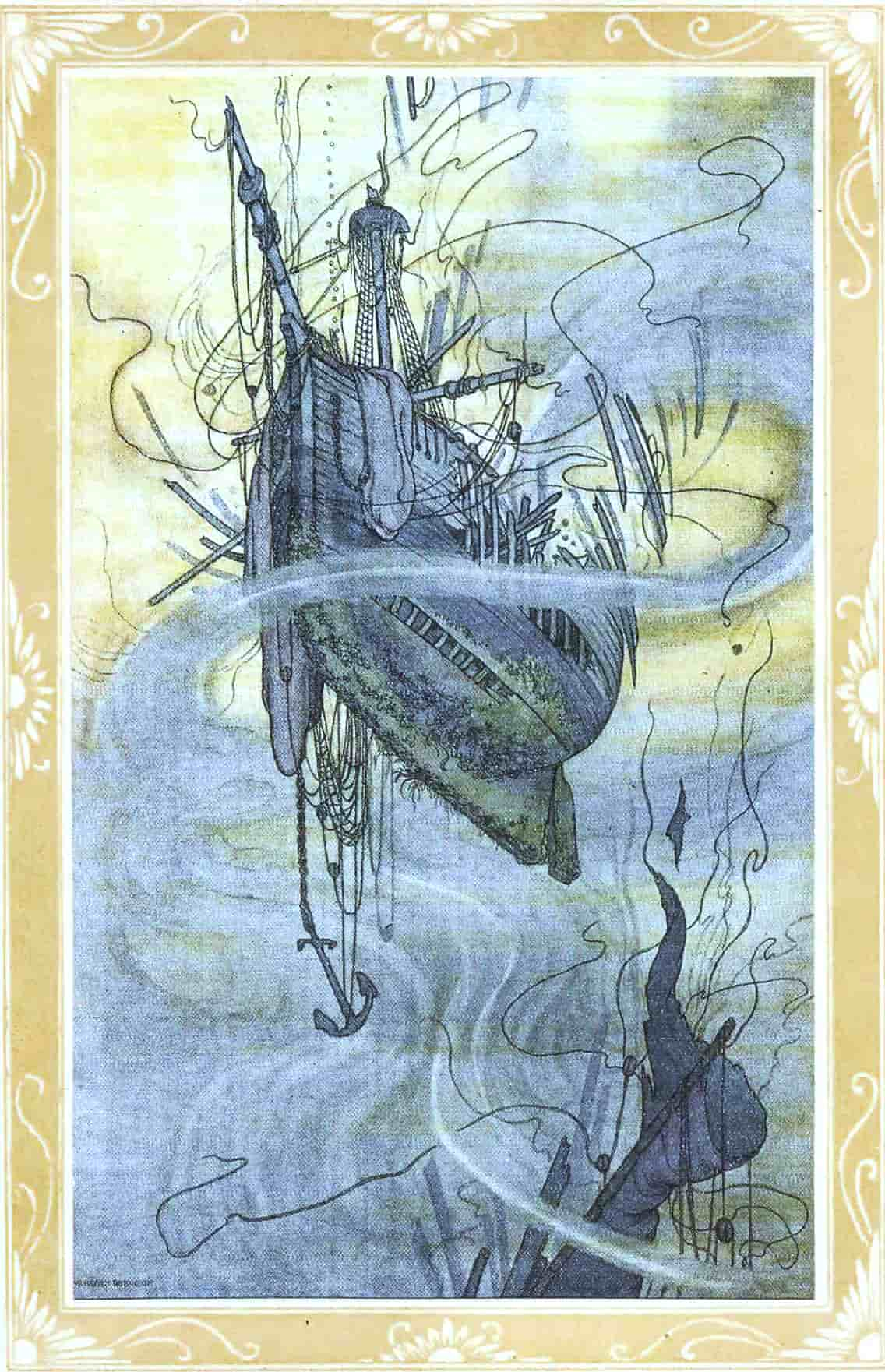

SHIPWRECK HAUNTOGRAPHY:

UNDERWATER RUINS AND THE UNCANNY

Shipwreck Hauntography: Underwater Ruins and the Uncanny (Amsterdam UP, 2021) asserts that nautical archaeology bears the legacy of Early Modern theological imperialism, most evident through the savior-scholar model that resurrects—physically or virtually—ships from wrecks. Instead of construing shipwrecks as dead, awaiting resurrection from the seafloor, this book presents them as vibrant if not recalcitrant objects, having shaken off anthropogenesis through varying stages of ruination. Sara Rich illustrates this anarchic condition with ‘hauntographs’ of five Age of ‘Discovery’ shipwrecks, each of which elucidates the wonder of failure and finitude, alongside an intimate brush with the eerie, horrific, and uncanny.

New Books Podcast

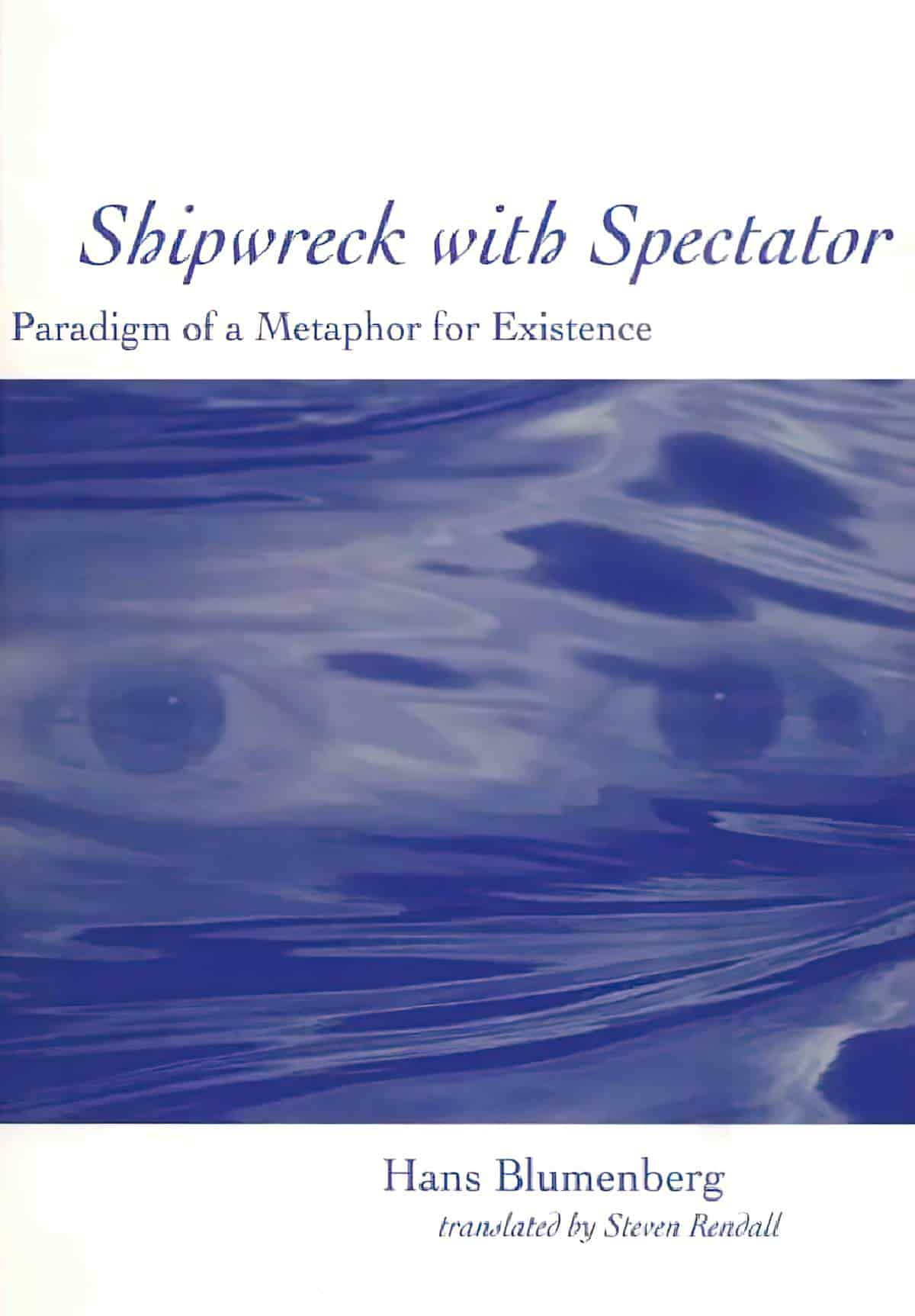

THE NAUTICAL METAPHORICS OF EXISTENCE

This is a phrase from Hans Blumenberg in Shipwreck with Spectator: Paradigm of a Metaphor for Existence, 1997.

Shipwreck with Spectator traces the evolution of the complex of metaphors related to the sea, to shipwreck, and to the role of the spectator in human culture from ancient Greece to modern times.

Shipwreck with Spectator traces the evolution of the complex of metaphors related to the sea, to shipwreck, and to the role of the spectator in human culture from ancient Greece to modern times. The sea is one of humanity’s oldest metaphors for life, and a sea journey has often stood for our journey through life. We all know the role that shipwrecks can play in this journey, and at some level we have all played witness to others’ wrecks, standing in safety and knowing that there is nothing we can do to help, yet fixed comfortably or uncomfortably in our ambiguous role as spectator. We see layer upon layer revealed in the meaning humans have given to these metaphors; and we begin to understand what metaphors can do that more straightforward modes of expression cannot.

He’s talking about all those metaphors we associate cross-culturally with ships:

- Ship wrecks on the high sea

- The juxtaposing safety of harbour

- Storms (the crises of life)

- Doldrums (the downtimes of life)

Often the representation of danger on the high seas serves only to underline the comfort and peace, the safety and serenity of the harbour in which a sea voyage reaches its end.

Hans Blumenberg, Shipwreck with Spectator

Of course, any web of metaphor can be subverted by a storyteller. Dracula was in fact a subversion of ship narratives, reflecting a change of attitude that was happening in the last decade of the 1800s.

Dracula was the anti-Ship story in the same way post WW2 Westerns are in fact anti-Westerns. In Dracula, Bram Stoker refused to glorify the mighty ship. Demeter, which transports the vampiric Count to Whitby, is not exactly Victorian romantic. That entire journey is a desperate struggle. There’s madness and horror and other Gothic tropes.

This story marked a shift in British identity, just as anti-Westerns marked a shift in American identity. Seafarers (and white pioneers in America) weren’t embarking upon a heroic and glorious enterprising journey at all. Very often, they were going to their death. Even if they survived, the realities of travel were not a fun time. Most people didn’t get rich. Imperial attitudes led to downfall when faced with unfamiliar seas and landscapes.

The Demeter of Dracula isn’t a literal ghost ship within the world of the story. This ship is made of solid ship stuff. But by the time she gets to Whitby, the vampire has attacked everyone onboard. So for story purposes we’re still talking about a ghost ship. The Demeter is still a vessel which allows audiences to contemplate that fuzzy border between life and death. All ships exist in this borderland, it’s just some are more ghostlike than others.

THE HAUNTED SHIP TALE

If you’d like to hear a ghost ship tale read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Haunted Ship” was published May 2019.

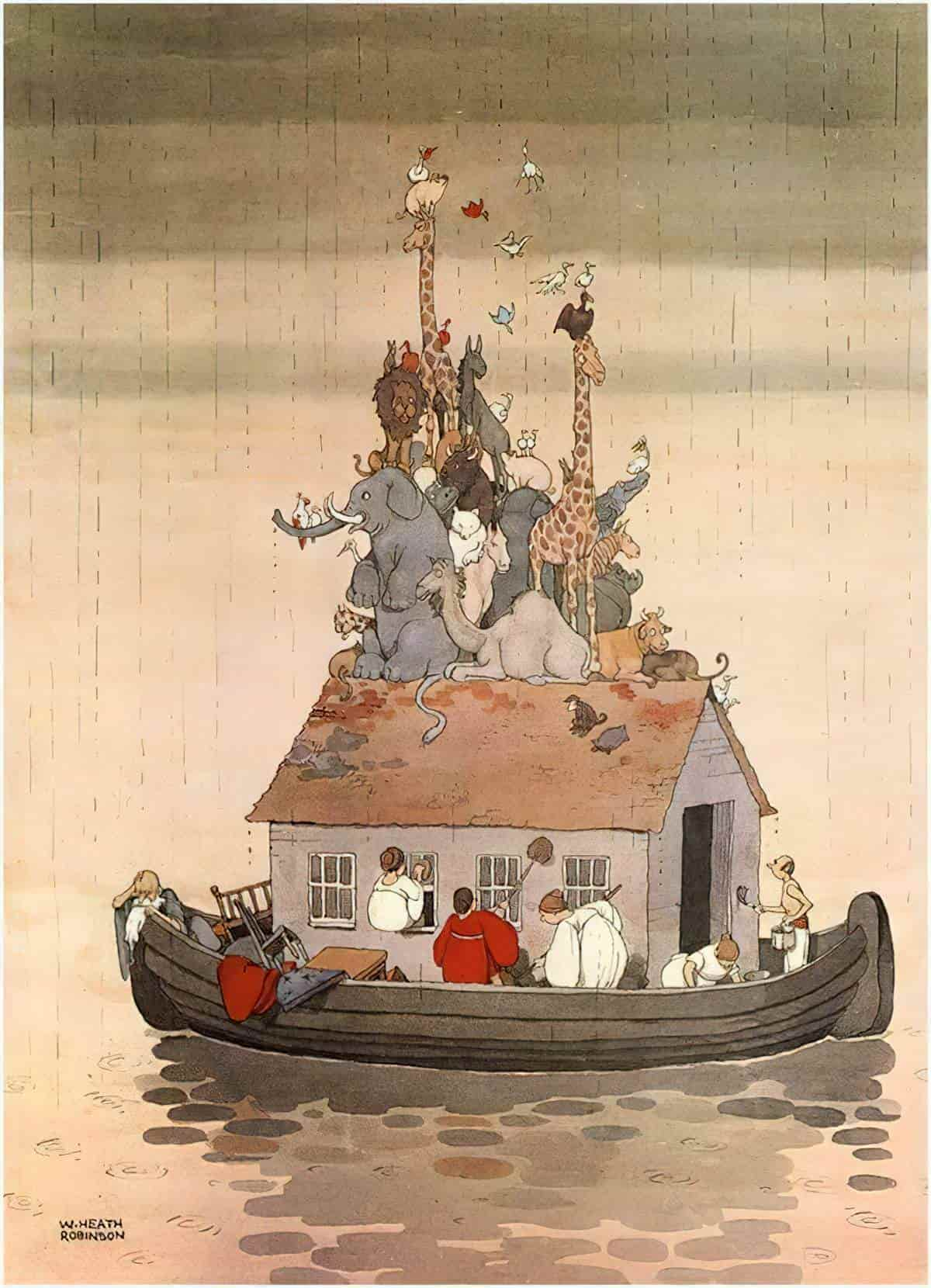

NOAH’S ARK

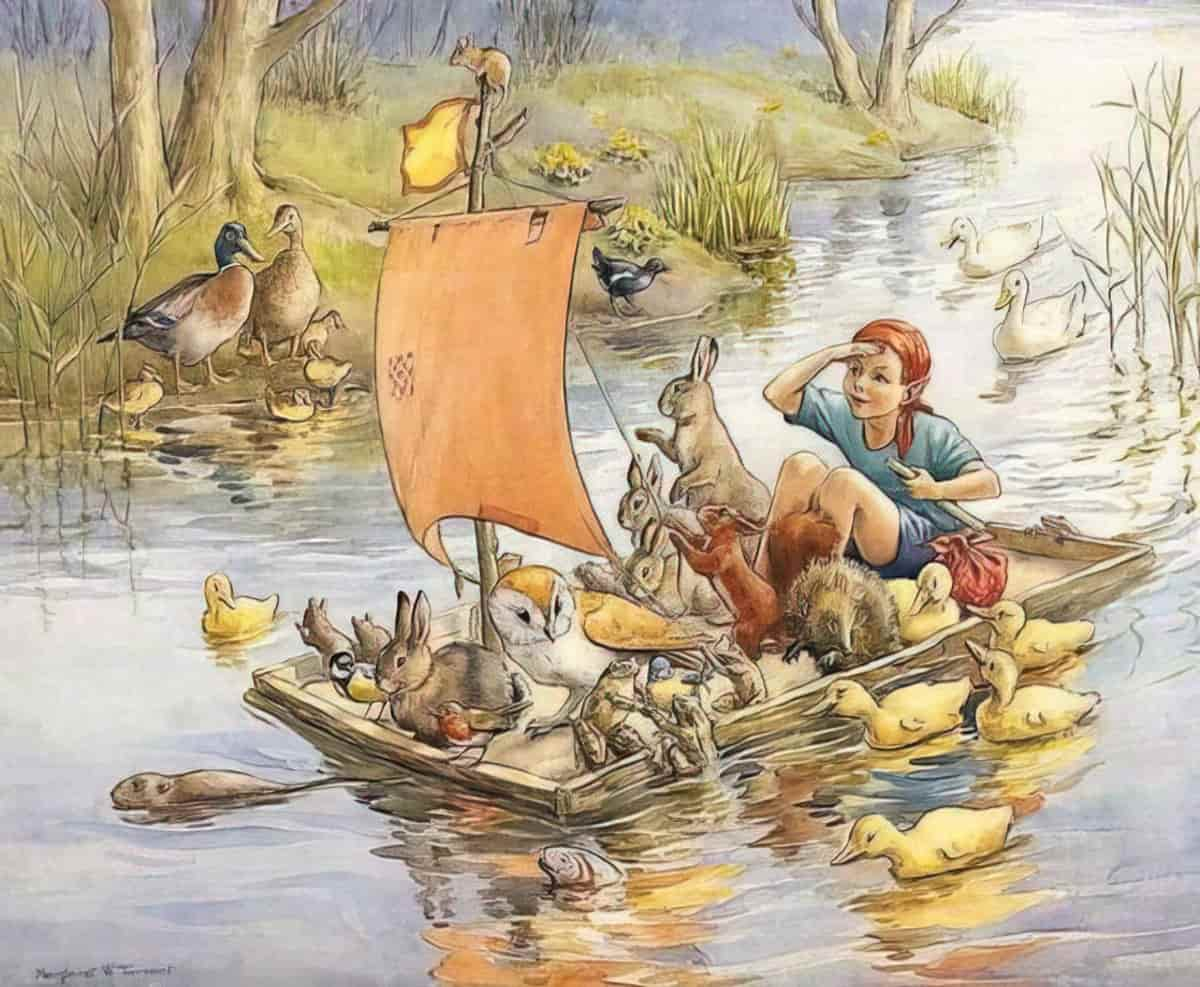

If Noah’s Ark existed, it would have looked more like a massive floating crate than like a storybook boat, but illustrators clearly enjoy creating a more aesthetically pleasing ship.

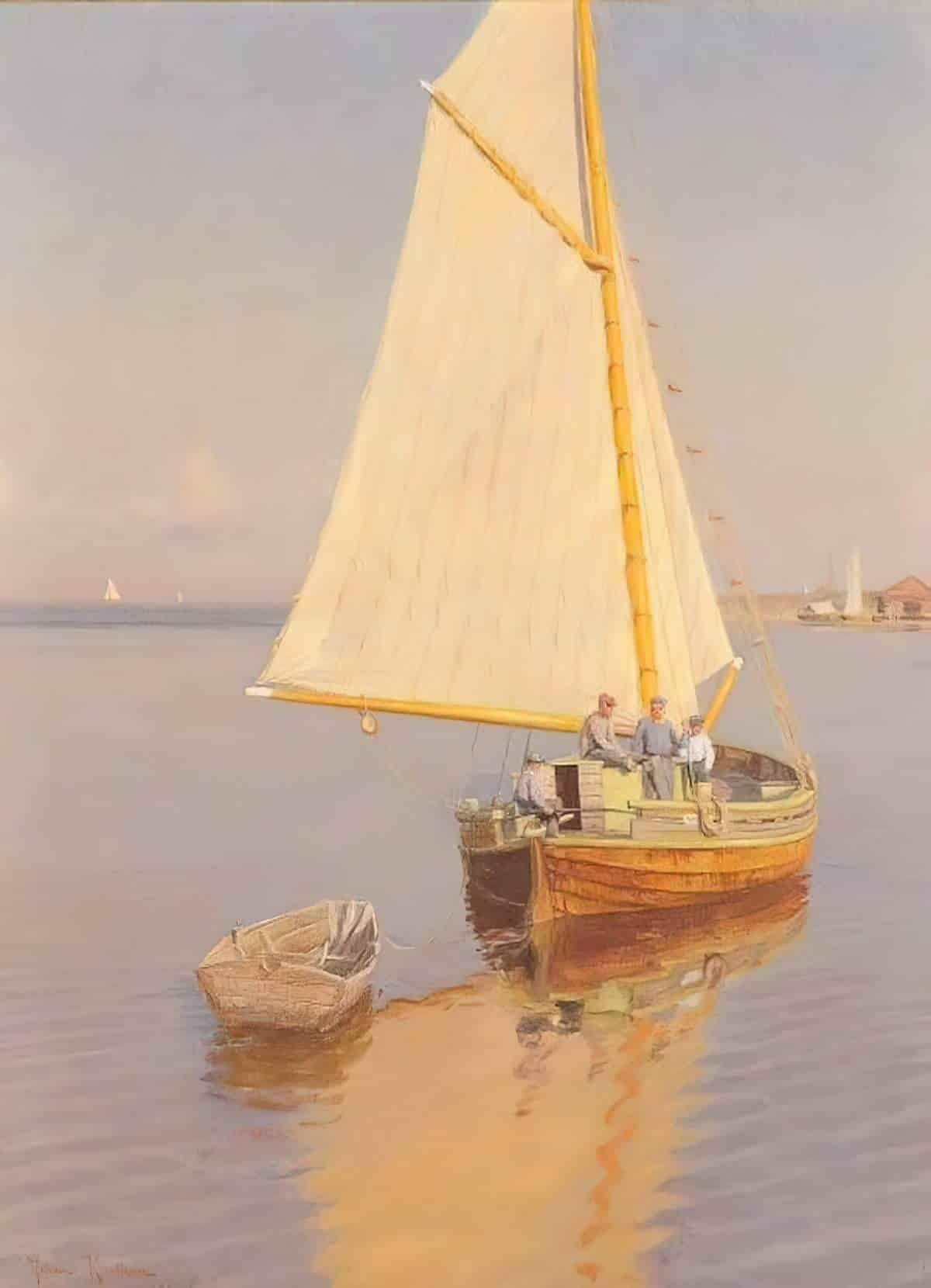

THE FRAILTY OF HUMAN ENDEAVOUR

Just as the image of billowing sails against a backdrop of clear sky can evoke these ideals of liberty and human ingenuity, the life at sea, at the mercy of Nature, is one very much grounded in age-old tradition and deep-seated superstition. As in both “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and Byron’s “Darkness”, the austere images of stranded and wrecked ships serve as grim reminders of the essential frailty of the human endeavor.

Ships (“Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and “Darkness”)

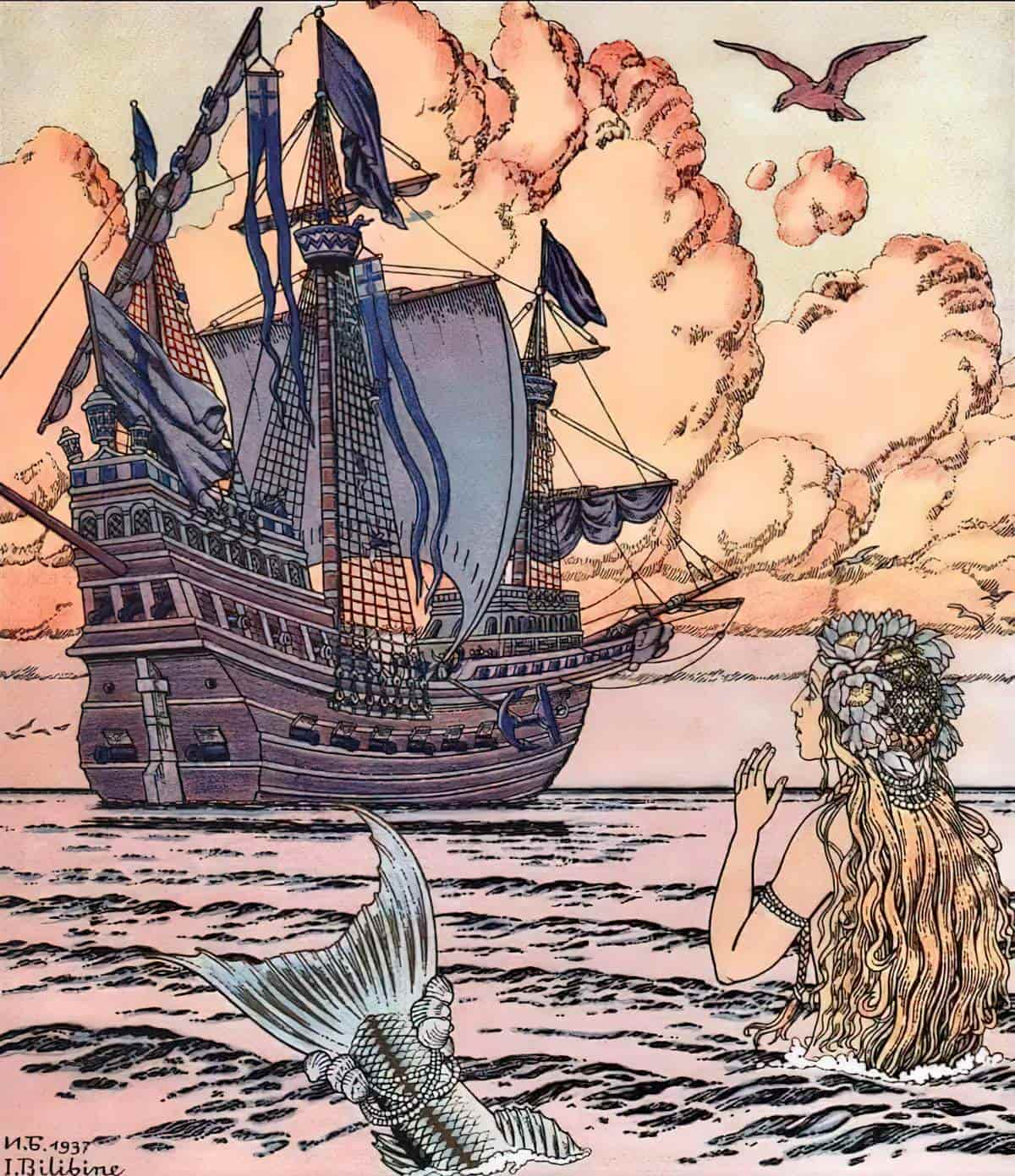

SHIP AS METONYM FOR COLONIAL INVADERS

Metonymy: when a word, name, or expression is used as a substitute for something else closely associated. For example, Canberra is a metonym for the Australian government.

“This ship…is England. So it’s every hand to his rope or gun. Quick’s the word and sharp’s the action! After all, surprise is on our side.”

Master & Commander

WHITE SAILS, BLACK SAILS

In the Ancient Greek myth about Minotaur, King Minos and the Labyrinth of Crete, Theseus, son of Aegeus decided to be one of the seven young men that would go to Crete. He planned to kill the Minotaur and end the human sacrifices to the monster.

Theseus promised his father King Aegeus that he would put up white sails coming back from Crete, allowing him to know in advance that he was coming back alive. The boat would return with the black sails if Theseus was killed.

Theseus did manage to kill the Minotaur. Ariadne’s thread he managed to retrace his way out. Unfortunately, Theseus was not a great person. He left Ariadne behind on the shore even though she saved his life, and was so drunk after celebrating his victory that he forgot to change the sails. His father therefore saw the ship approaching and assumed his son was dead. King Aegeus suicided by drowing himself in the sea, now called the Aegean Sea.

The premature, completely unnecessary suicide is utilised in a number of modern stories including The Mist by Stephen King and in one of the stories of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, directed by the Coen Brothers.

BOATS AND THE HUMAN BODY

In the most general sense, a ‘vehicle’. Bachelard notes that there are a great many references in literature testifying that the boat is the cradle rediscovered (and the mother’s womb). There is also a connexion between the boat and the human body.

A Dictionary of Symbols, J.E. Cirlot

SHIPS AND BOATS AS SECOND HOMES

Most people like paintings of ships. You probably know someone with a painting of a ship on their wall. Perhaps we like to imagine the adventure promised by ships… but only while cosied up inside our own safe homes.

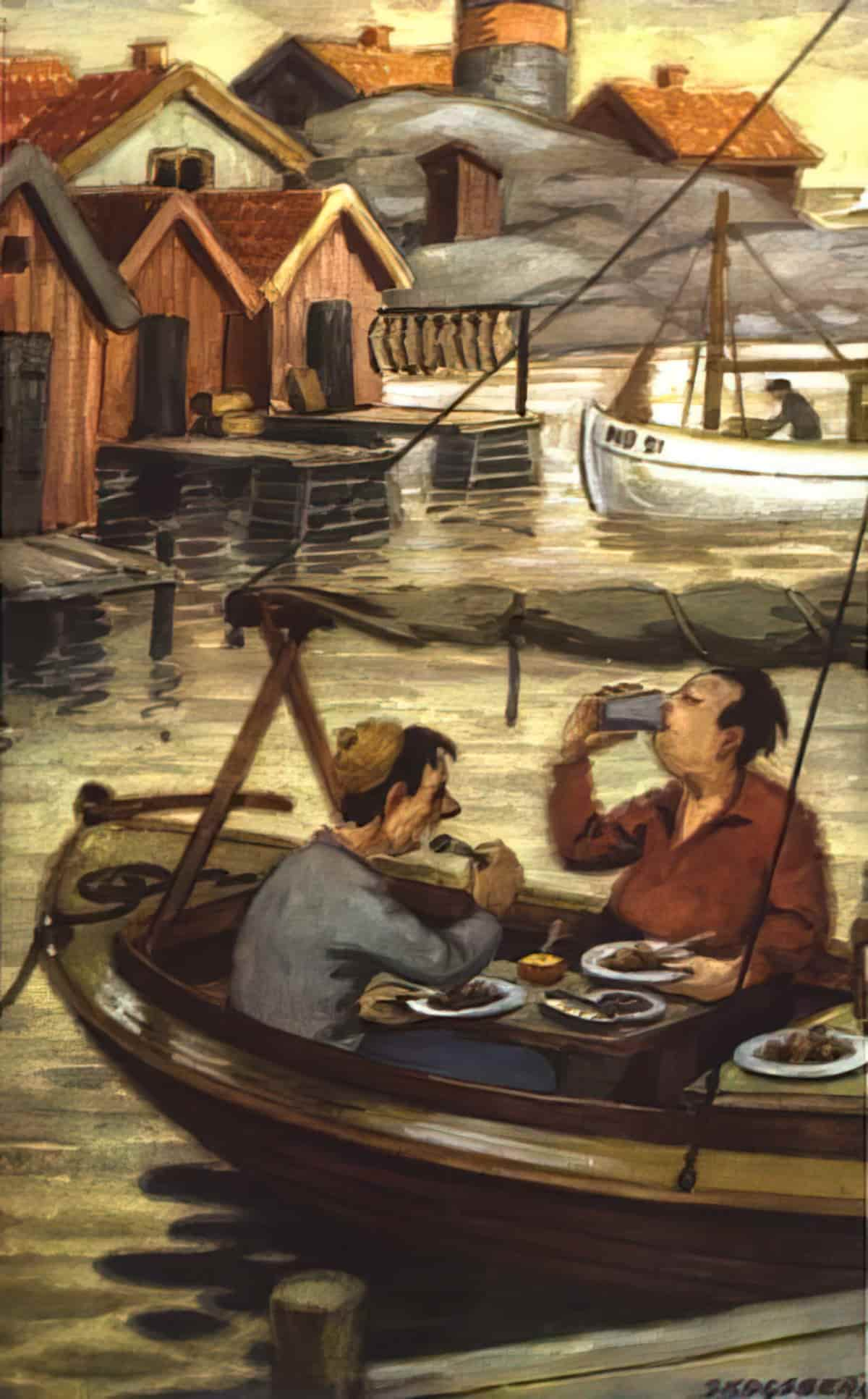

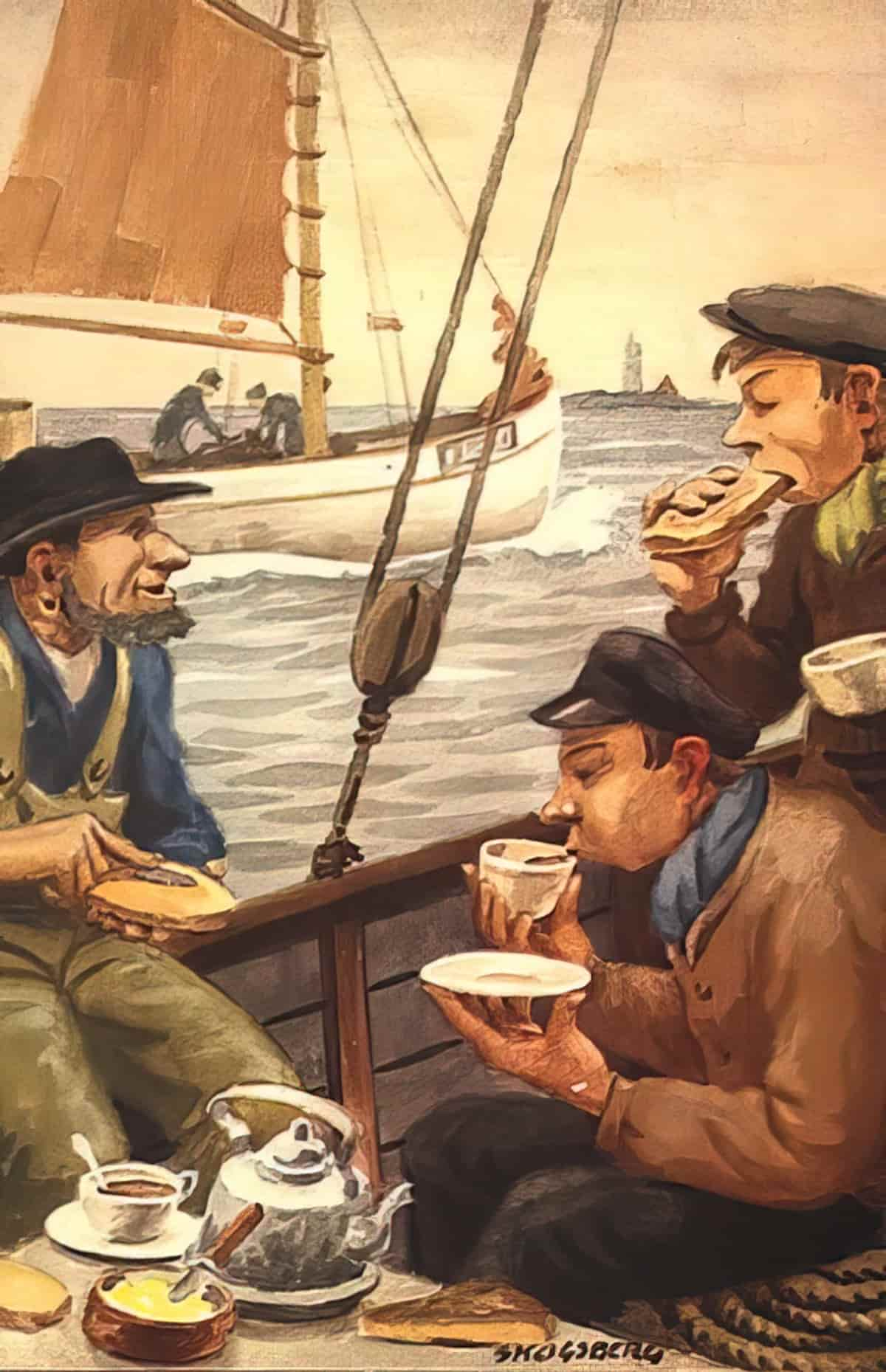

These illustrations, also by Harald Skogsberg, show the homely potential of a boat — a second home, where you eat and drink with mates.

The Victorians, who were, after all, great engineers, and who were the first to glorify the idea of progress, never felt the need to develop what might be called an engineering aesthetic. The interiors of steamships, trains, and tramways—extraordinary inventions—always took comfortingly familiar forms. The stateroom of a liner resembled a suite at the Ritz.

Home, Witlold Rybczynski

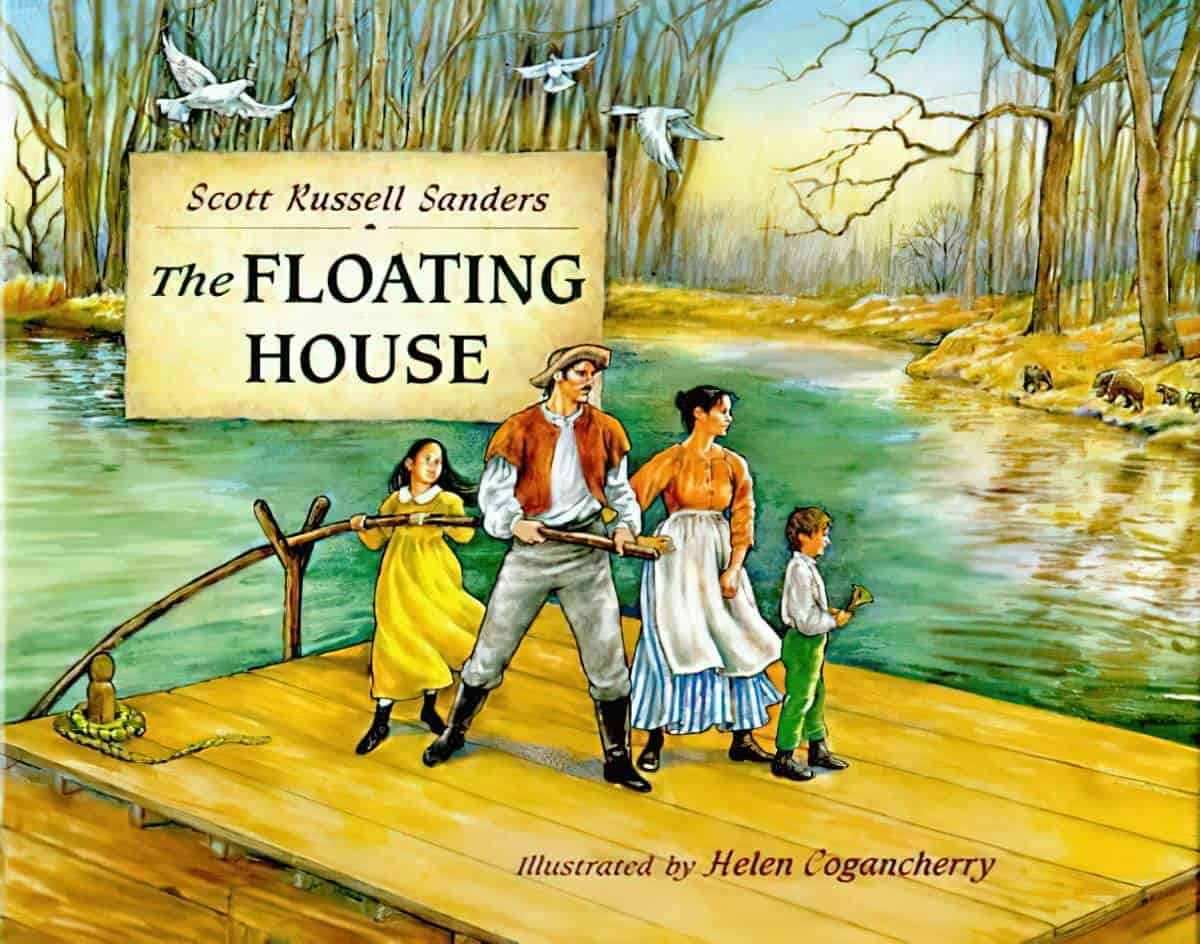

It’s 1815 and the McClure family is floating down the Ohio River in a flatboat that carries their wagon, farm tools, and household supplies as well as the family’s farm animals. When they arrive in Jeffersonville, Indiana, they will take their boat apart and use the wood to build their new house.

Likewise, trains were designed to look like small home parlours. Later in the book, when describing the Swiss pavilion as designed by cousins Charles-Edouard and Pierre Jeanneret, Rybczynski observes that the interiors of the pavilions were as ‘unfinished’ looking as the exteriors, emanating an industrial atmosphere reminiscent of a ship’s boiler room. So while ships were doing their best to look like homes, later, homes seemed to be doing their best to look like ships.

from The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

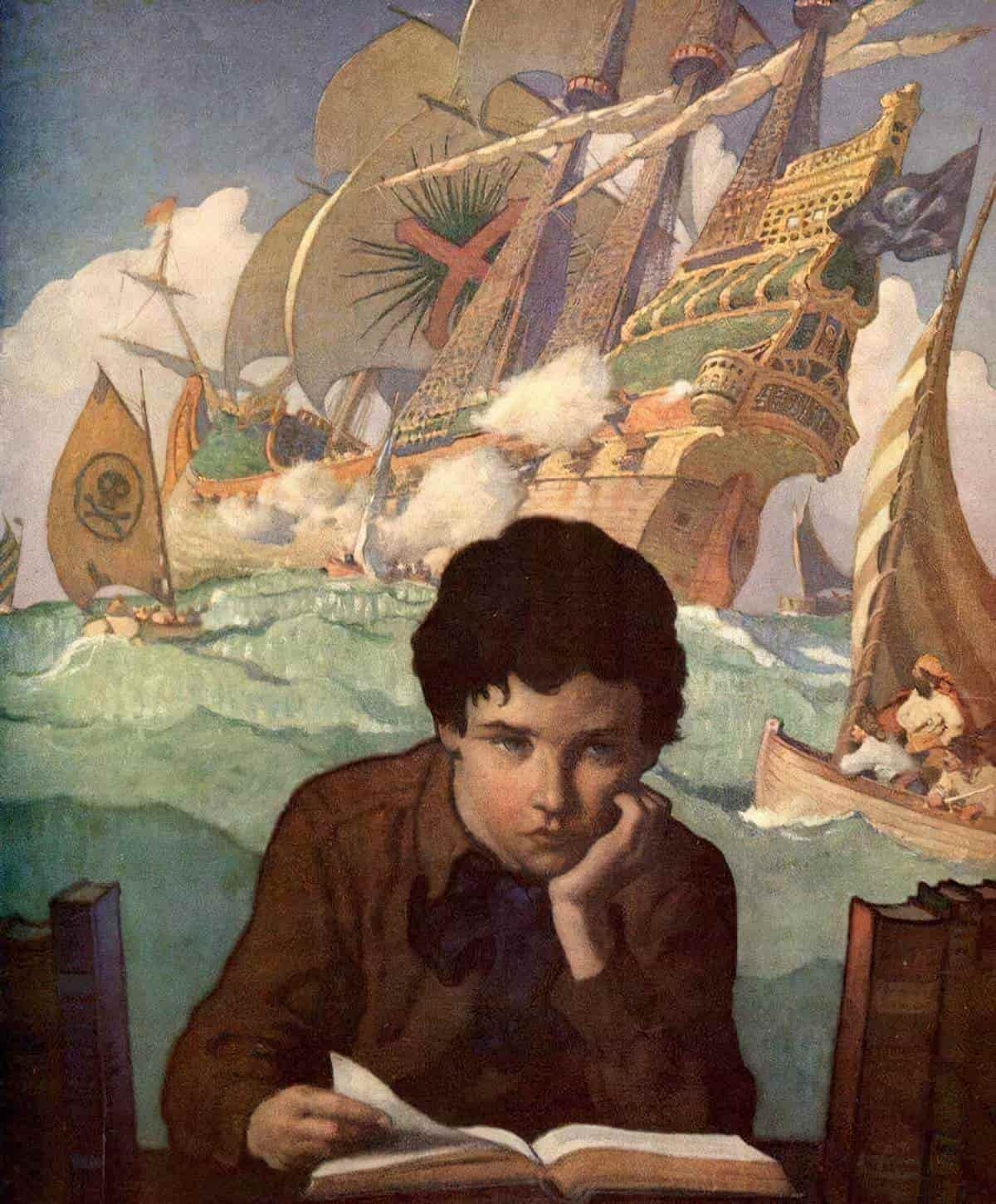

The painting below by N.C. Wyeth is a wonderful chimera of the Dream Boat (apologies to Gaston Bachelard). Ships and boats featured prominently in 20th century literature aimed at boys. “Imagination” is an amalgamation of the main seafaring archetypes:

(The following year, Norman Rockwell painted Lands of Enchantment, perhaps inspired by Wyeth’s cover.)

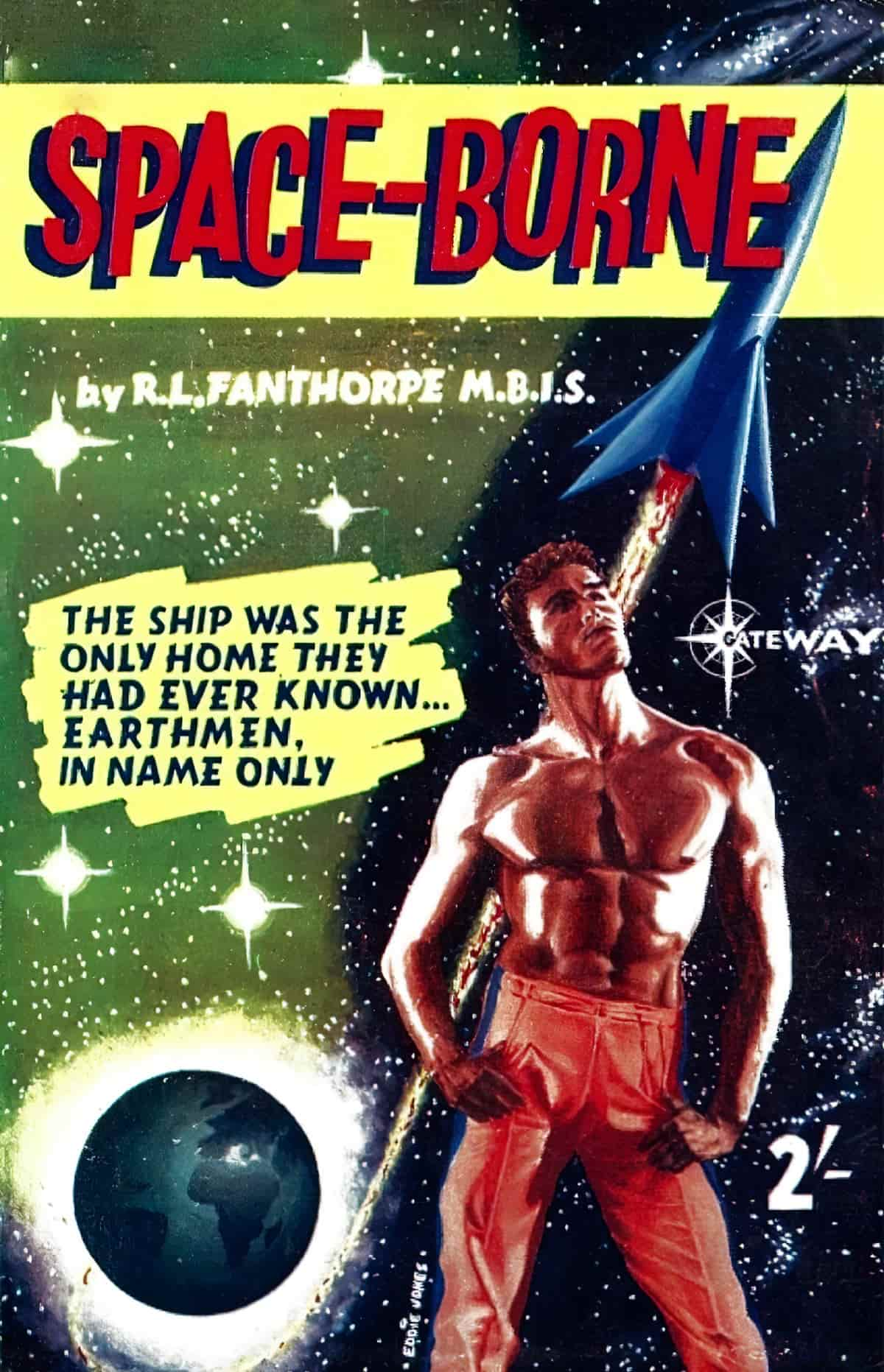

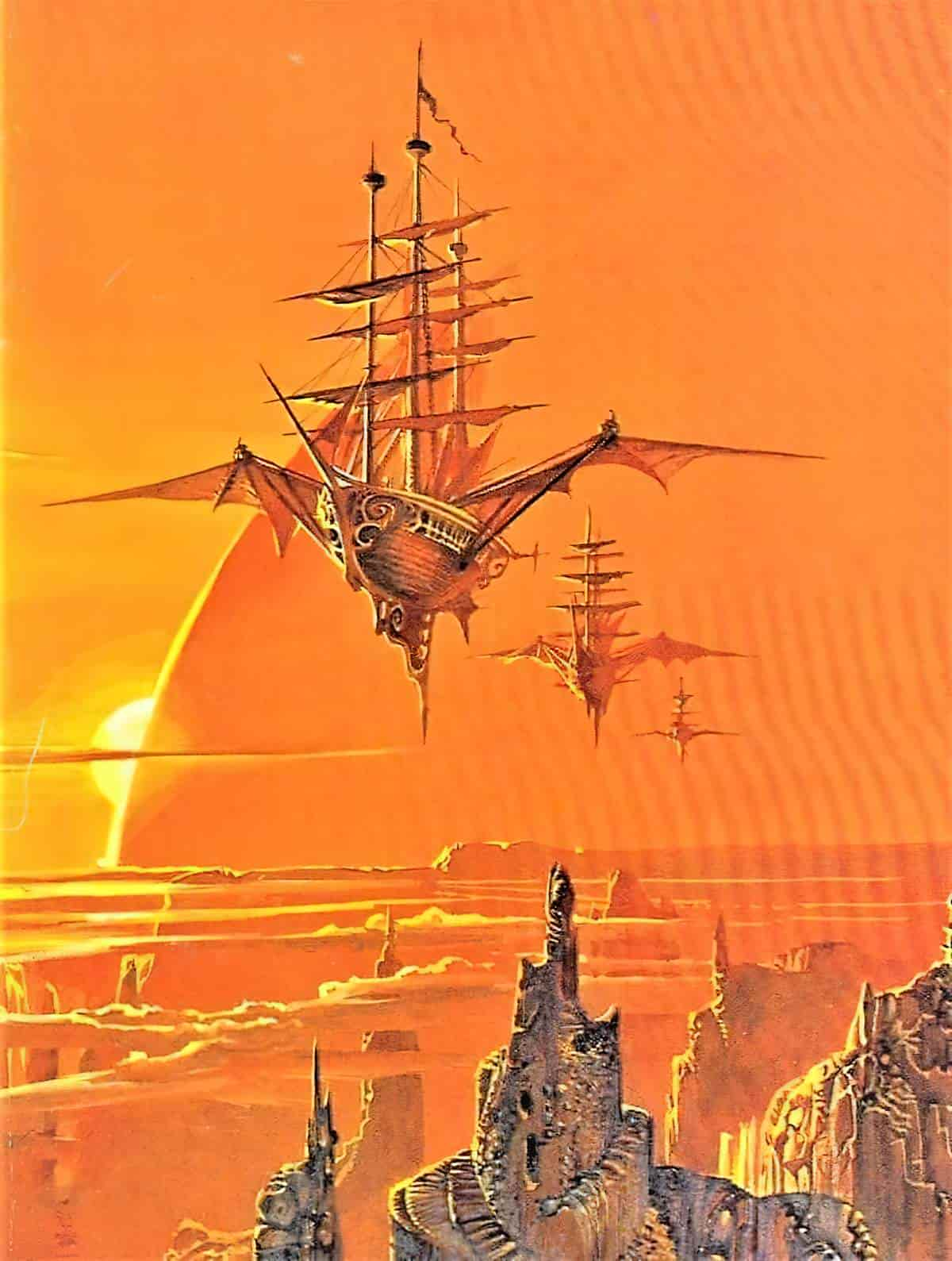

This discussion of ships includes space ships, for in science fiction the ship becomes a spaceship. Consider outer space is metaphorically the same as the ocean — only the setting differs.

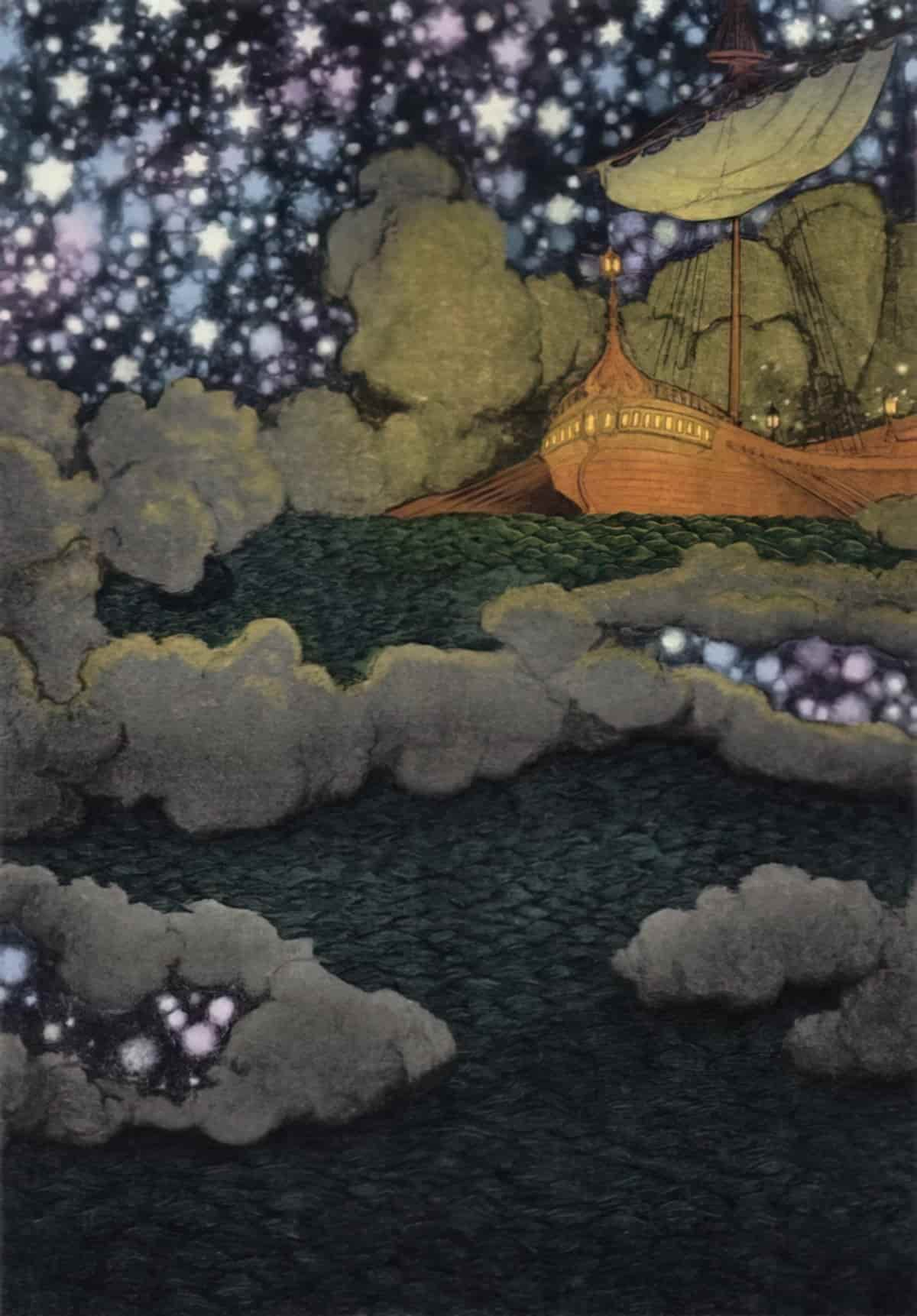

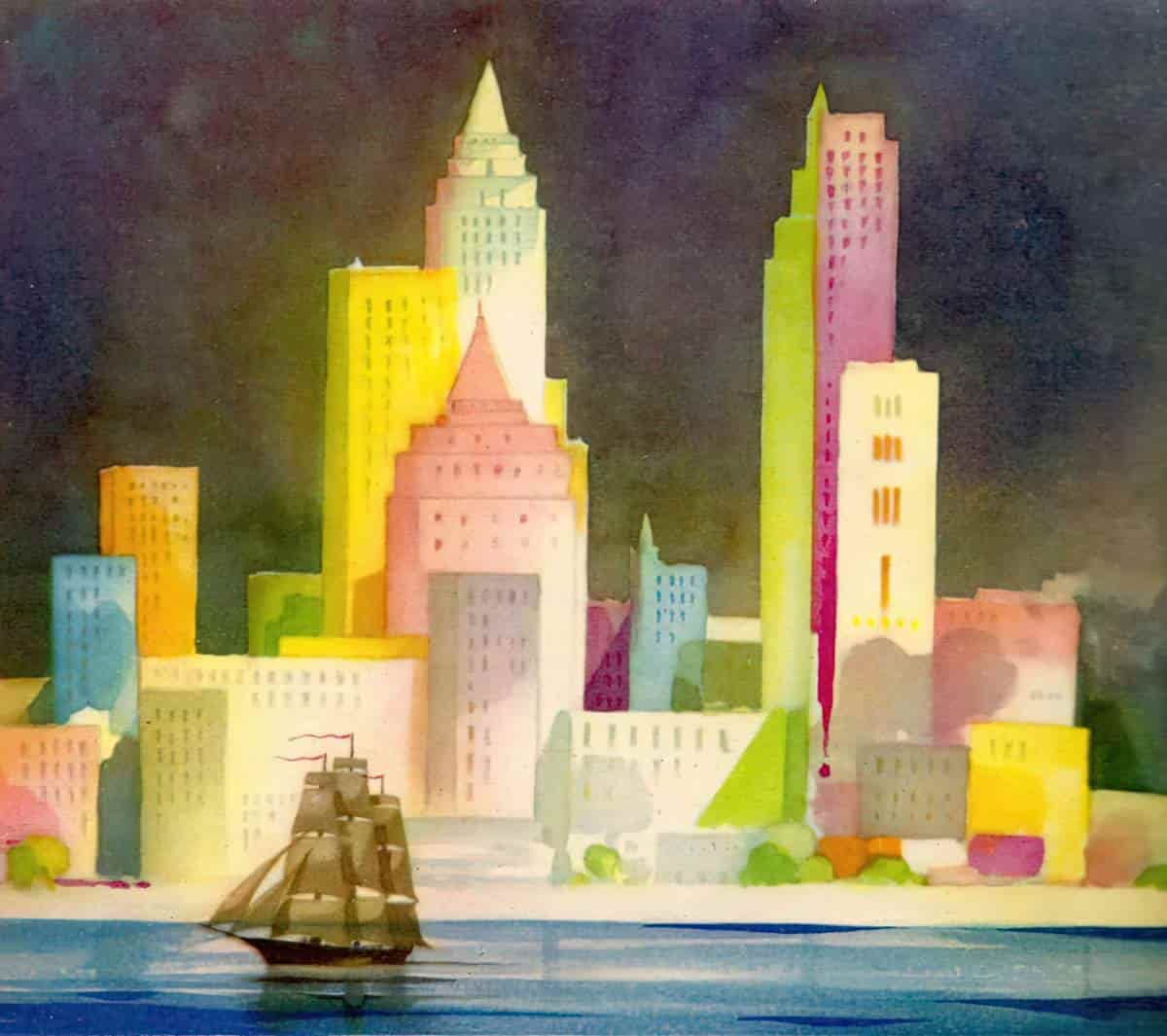

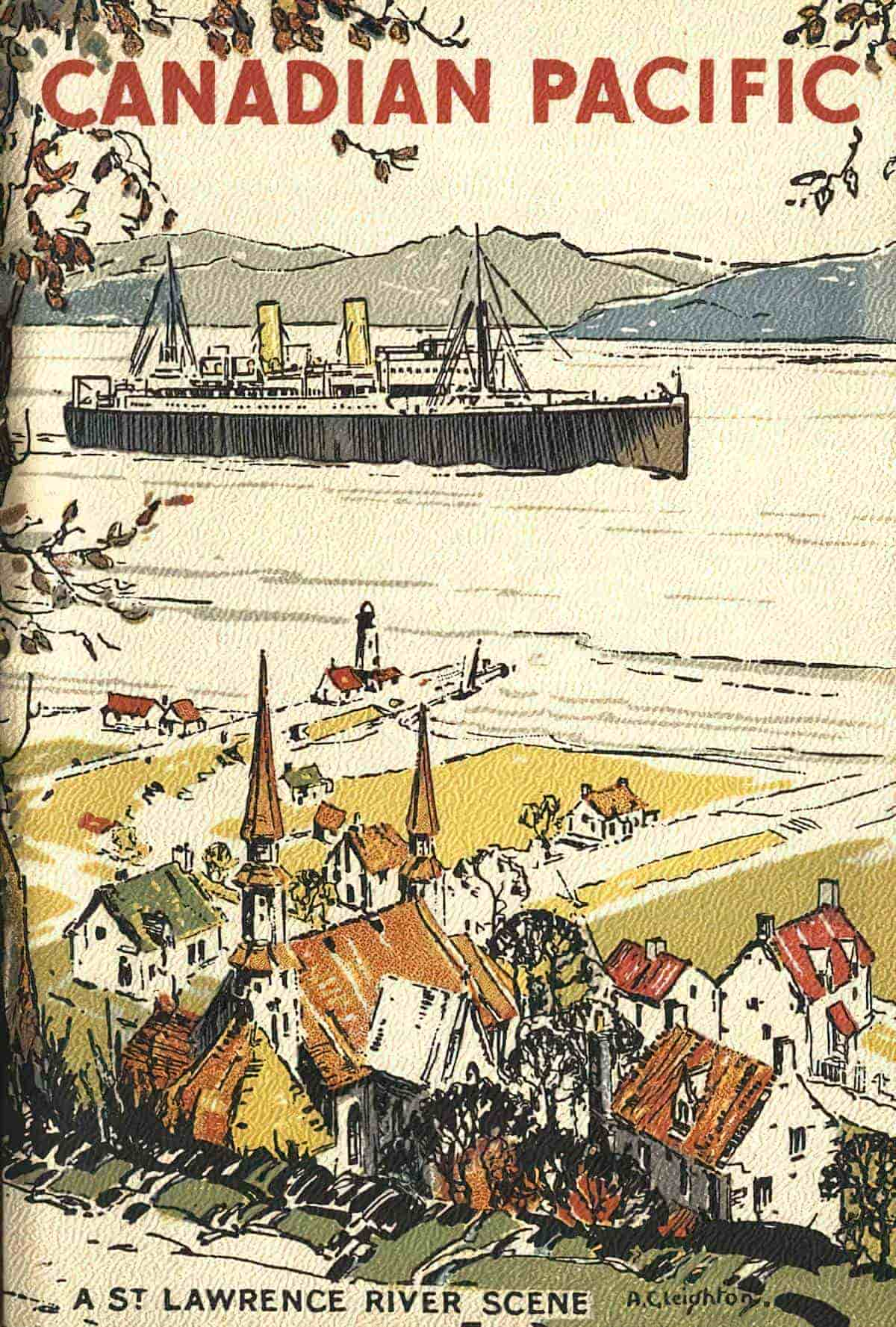

The illustration below offers a glimpse into how a ship on the horizon can look, to the landlubber, as if it is a part of the sky as much as it is a part of the sea.

SAD GOODBYES

Bobby Shafto’s gone to sea

Silver buckles on his knee.

He’ll come back and marry me.

Bonny Bobby Shafto!

See also: Looking Out To Sea, a collection of images.

THE HEALING POWER OF SHIPS

In Enid Blyton’s 1950 children’s story The Pole Star Family, Mike, Belinda and Ann have had a miserable summer. They have all been ill. But then Granny decides to take them on the cruise of a lifetime. They sail away on the gorgeous Pole Star and have the most fun ever! They visit towns with palaces and exotic markets in wonderful countries such as Portugal, the Canary Islands and Africa.

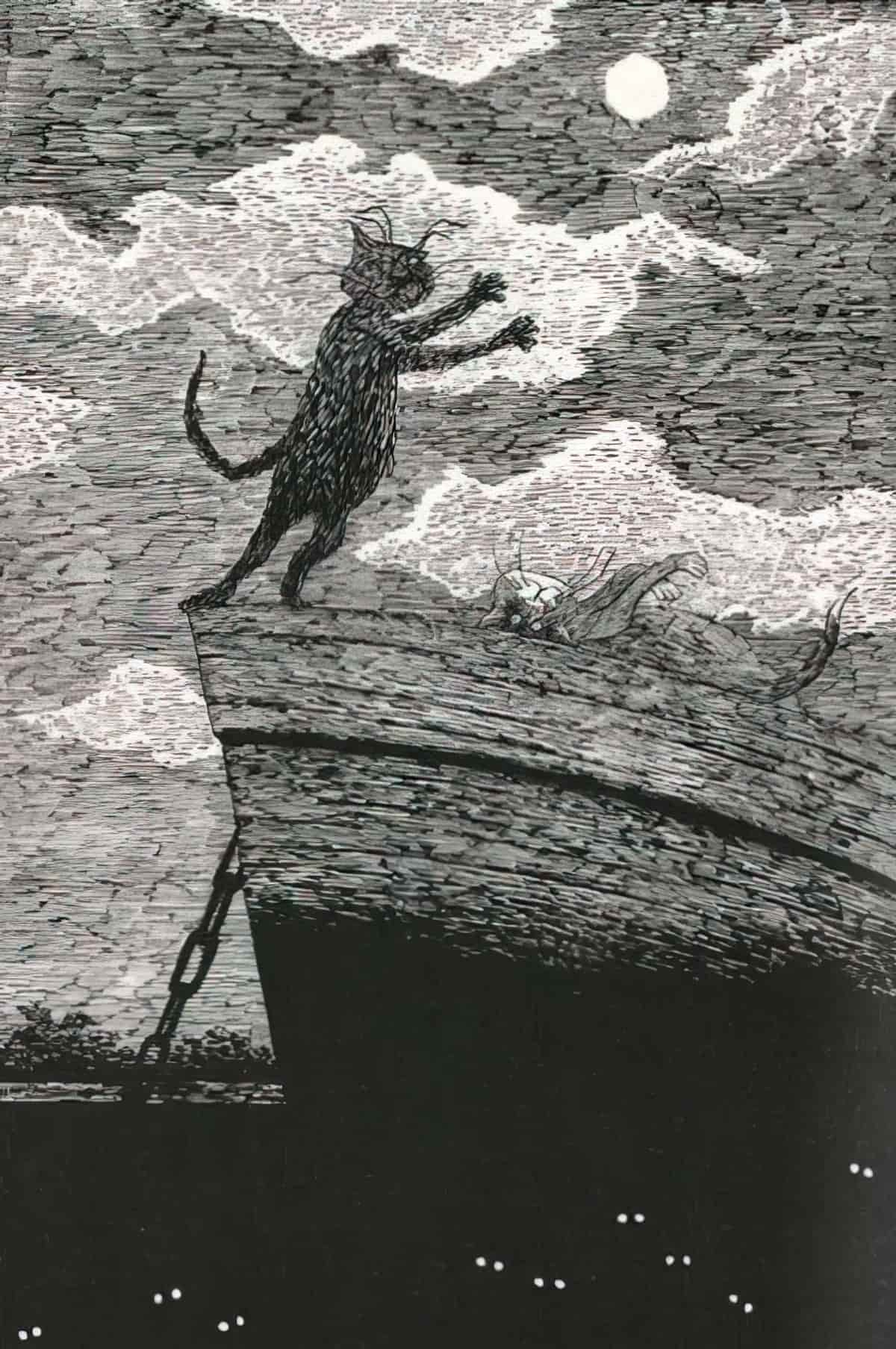

SHIP AS GOTHIC SPACE

In literature, ships can function as gothic spaces in a variety of ways. Shipwrecks, for example, conceal and preserve dark secrets that haunt the living — in Wilkie Collins’ Armadale (1866), Midwinter passes a night of terror on the wreck of the timbership, next to the cabin in which his father murdered Allan’s father; a wreck conceals the body of the eponymous Rebecca in Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel, and its discovery exposes answers to the puzzles oppressing the second Mrs de Winter. Even viable ships can be claustrophobic spaces, or expose the extreme psychological effects of isolation, illness, or starvation, such as in Joseph Conrad’s Shadow Line (1915), or in Prendick’s near brush with cannibalism in the dinghy of the Lady Vain in H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr Moreau (1896). In more explicitly supernatural texts, gothic ships cross normally uncrossable boundaries between life and death, sea and air, as does the Flying Dutchman in Frederick Marryat’s The Phantom Ship (1839).

Emily Alder, “Dracula’s Gothic Ship” from Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies (Autumn 2016)

Ships make for great gothic spaces because they exist in that in-between state. Foucault named ships as examples of heterotopias (other places). Note that ships are only heterotopic while they’re at sea. When they’re in dry dock they’re still subject to the rules of the land, like the rest of us land lubbers.

The ship is ‘a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea’.

Michel Foucault

We might also use the word ‘liminal‘.

In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), the ship (called Demeter, meaning Goddess of Fertility) exists in a liminal, in-between state and so does the Count himself.

Sailors themselves exist in the state between life and death, a reflection of the danger of pre-20th century sailing.

‘Sea men are to be numbered neither with the living nor the dead’, explained a minister familiar with the dangers of life at sea. ‘In their daily work, mused another cleric, seamen ‘border upon the Confines of Death and Eternity, every moment’

Marcus Rediker quoting two 18th Century clergymen in Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 1700-`1750, published 1987.

In storytelling, the ship is what I call a symbolic paradox.

On a sea voyage, a ship is existentially unreliable; it is a space in which more than one (potentially conflicting) state or reality can hold true at the same time. In gothic narratives, ships, like castles, abbeys, cities, or prisons, can become self-contained, oppressive systems governed by their own internal rules, while their material existence as floating objects renders them isolated and unstable in unique ways.

Emily Alder, “Dracula’s Gothic Ship” from Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies (Autumn 2016)

GHOST SHIPS

Here’s the interesting thing about Dracula: There were already a whole lot of scary ideas around ships by the time Dracula came along. Ships are scary because they so often cause literal death. The supernatural character of Dracula takes those metaphors around heterotopia and liminality and makes them literal within the world of the story. Dracula is literally the undead, who has come back to live among us, spanning between the living and the dead.

Ships are frequently shrouded in mist and fog, which lends them nicely to ghost stories, and to people who think they can actually see ghost ships.

Were these people really seeing just fog, though? Perhaps they were seeing more than that. When people saw ‘ghost ships’ they may have been seeing ‘derelicts’ (abandoned ships which haven’t sunk). Back in the day (in the 1800s and into the 1900s) these ships could hang around in sea lanes for years and years. There wasn’t anyone getting rid of them for safety reasons or whatever.

The vivid, often eerie, superstitions, tales and rituals of the sea were the sailor’s response to danger – immediate and uncontrolled. As a sailing-ship beat for weeks across the Southern Ocean, domain of the albatross, meeting no one in the lonely wastes, her crew felt an urgent need to appease the sea-gods. Even today, with engines, iron or fibreglass hulls, and less credulous seamen, much traditional sea lore has survived, especially in the fishing fleets.

Stories of phantom ships and crews (from the Flying Dutchman onwards), of the perennial sea-serpent, of lonely lighthouses; rituals such as the crossing-the-line ceremonies or blessing the fishing fleet; old weather lore, sailors’ chanties and sea language, taboos and talismans, precautions taken at keel-laying or launching – all these are recorded and interpreted here.

For everyone who enjoys strange stories and the chilly fascination of the unconquered sea, or thrills to watch man pitting himself against merciless elements, this book is a delight and a mine of information. Margaret Baker is unrivalled at collecting traditions of the past and showing the part they have played for generations of men in their daily lives.

Added to that, when a ship goes missing, taking your loved-one with it, you never get to know what happened to them. Human brains don’t do very well with partial narratives. We’re inclined to fill in the details, whether we wish to or not. A ghost story is at least a story, and a supernatural story is better than no story at all.

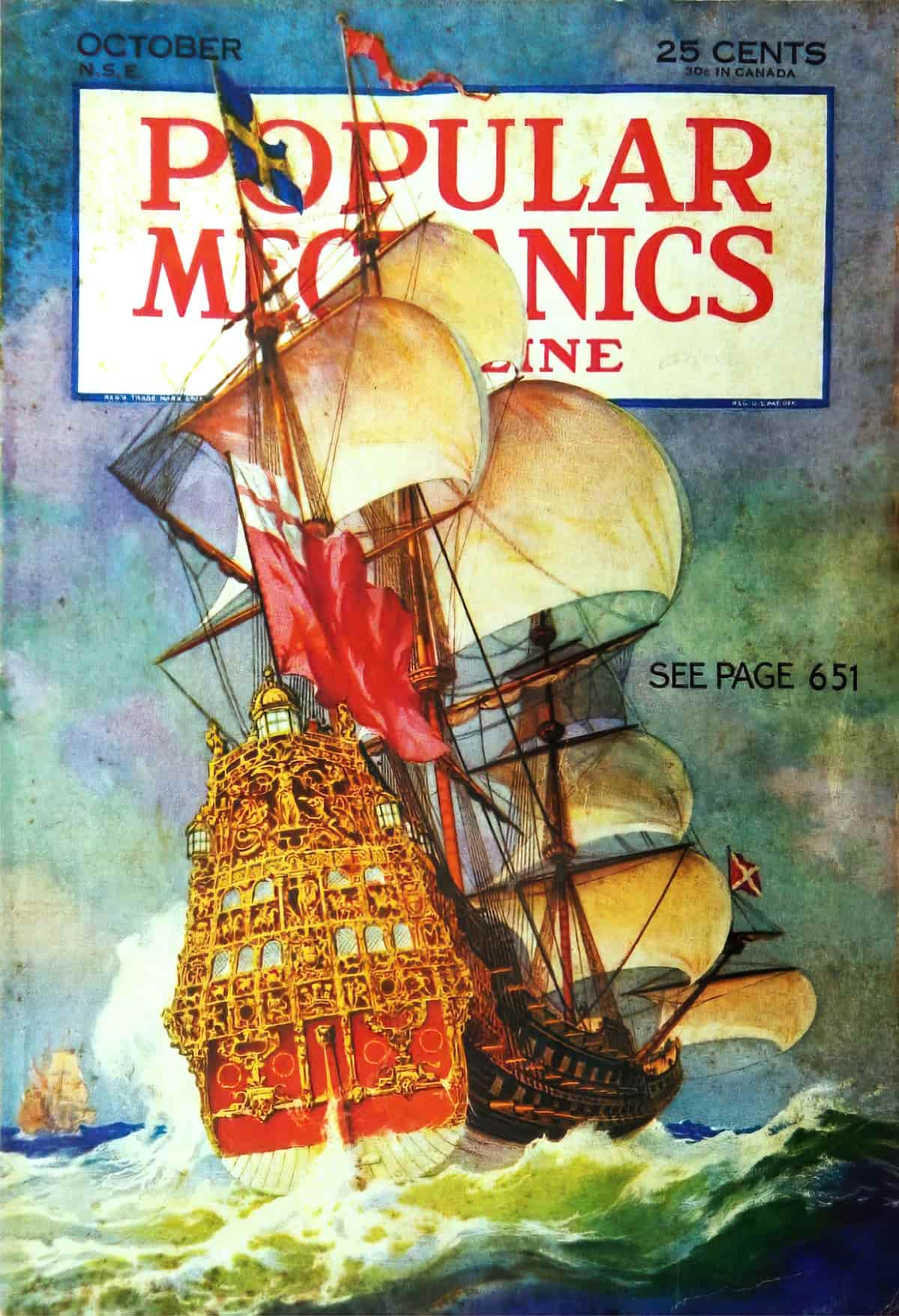

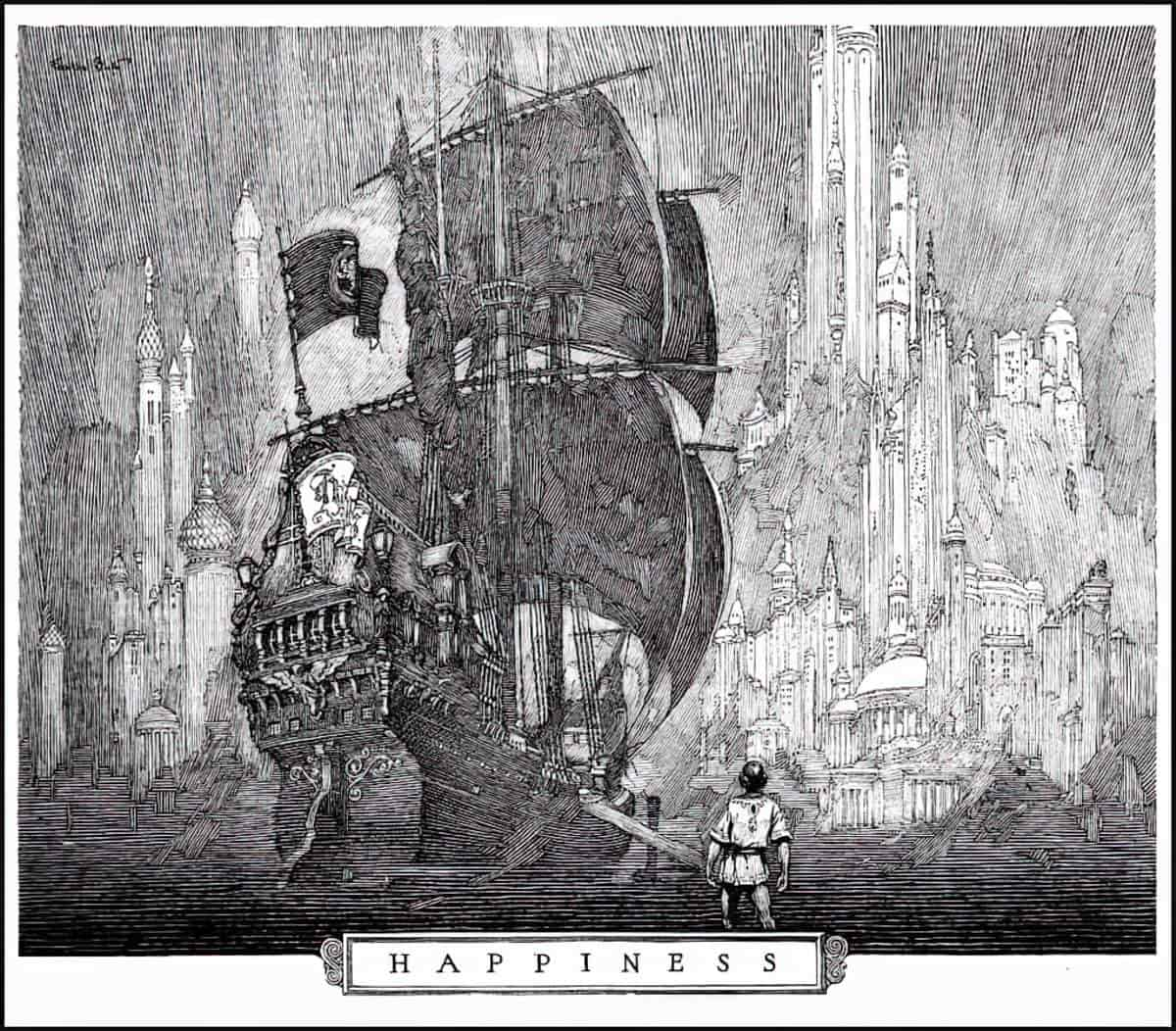

THE INVINCIBLE LARGE SHIP

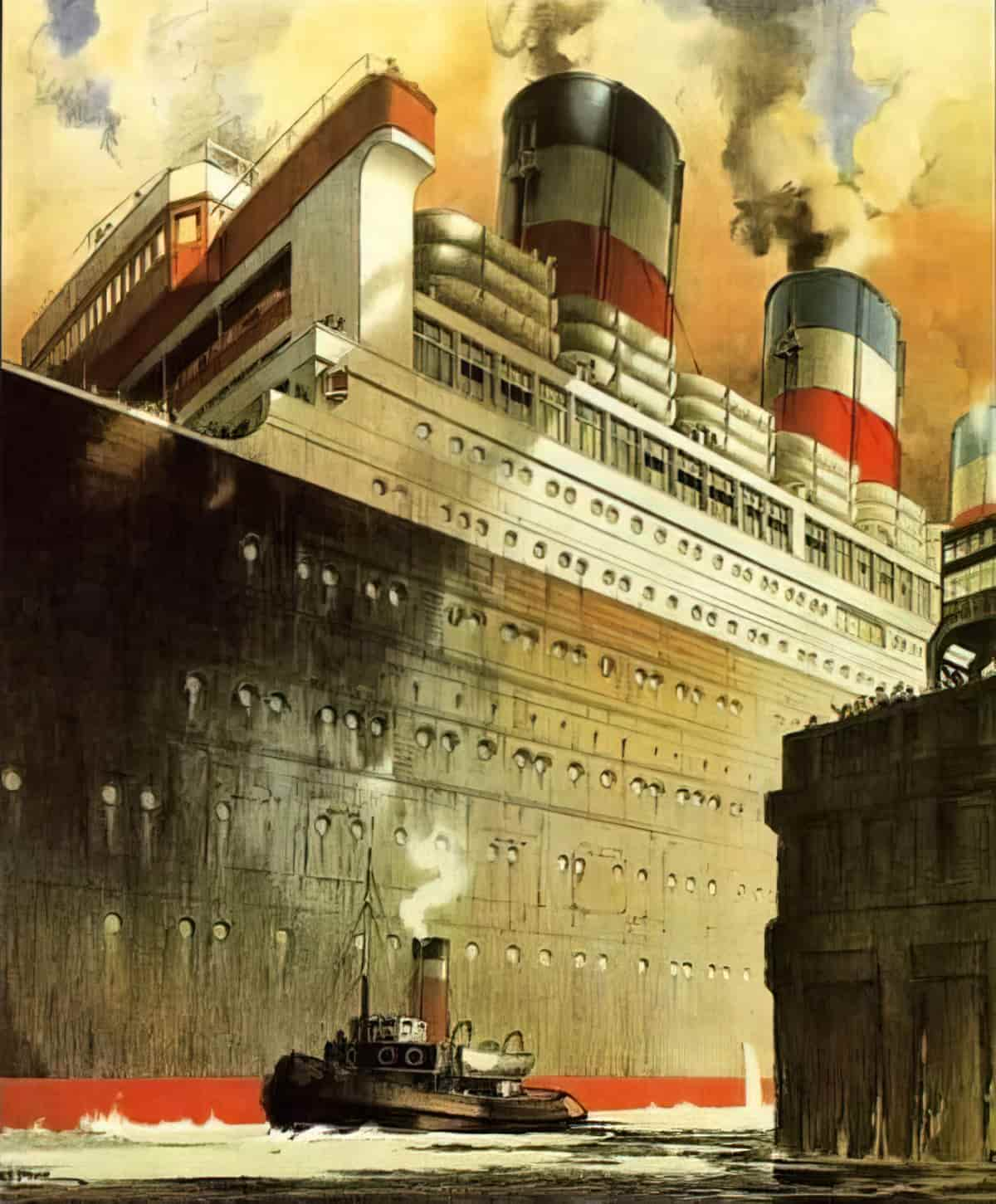

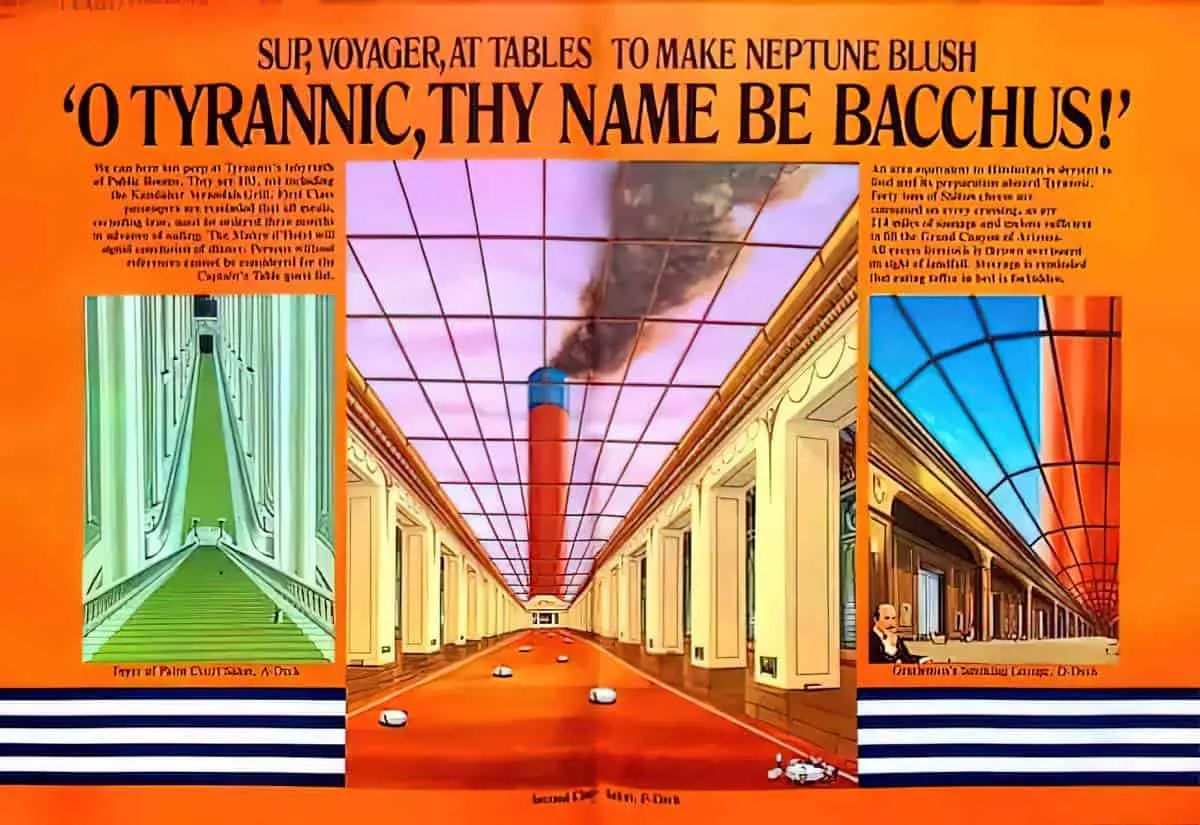

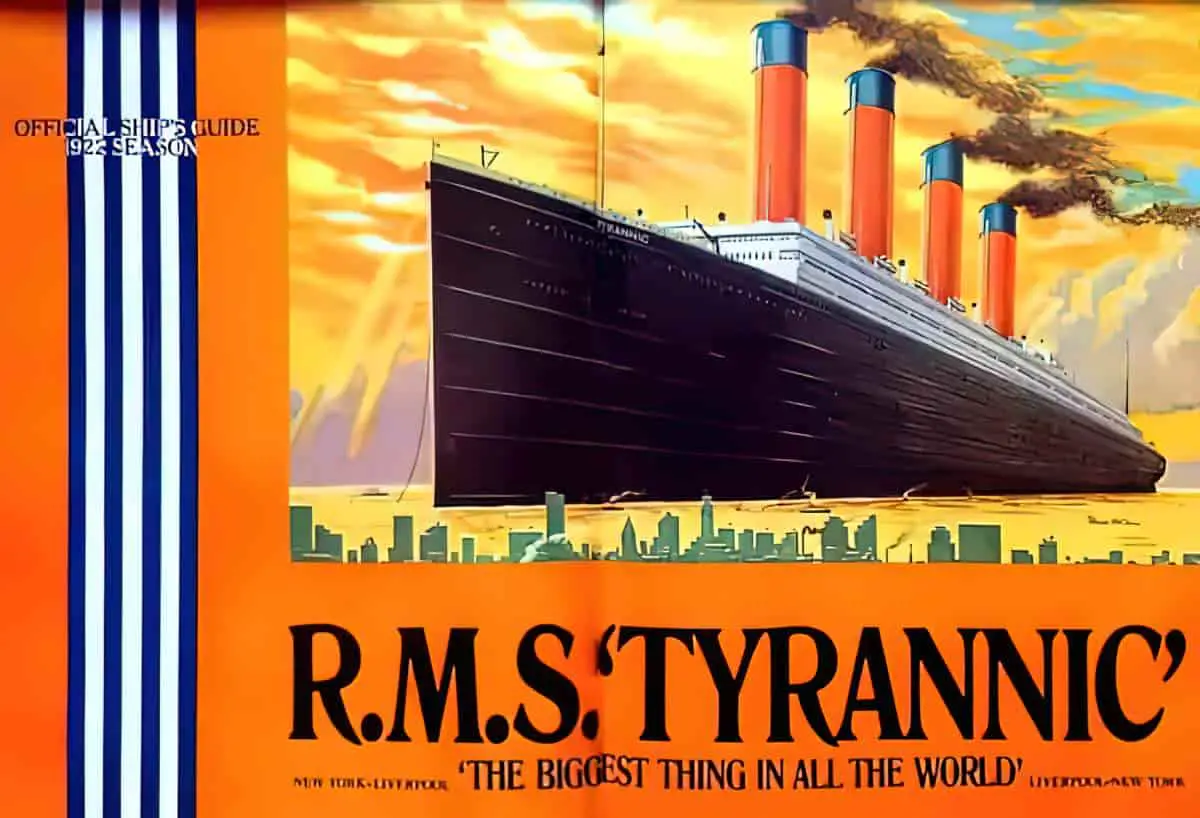

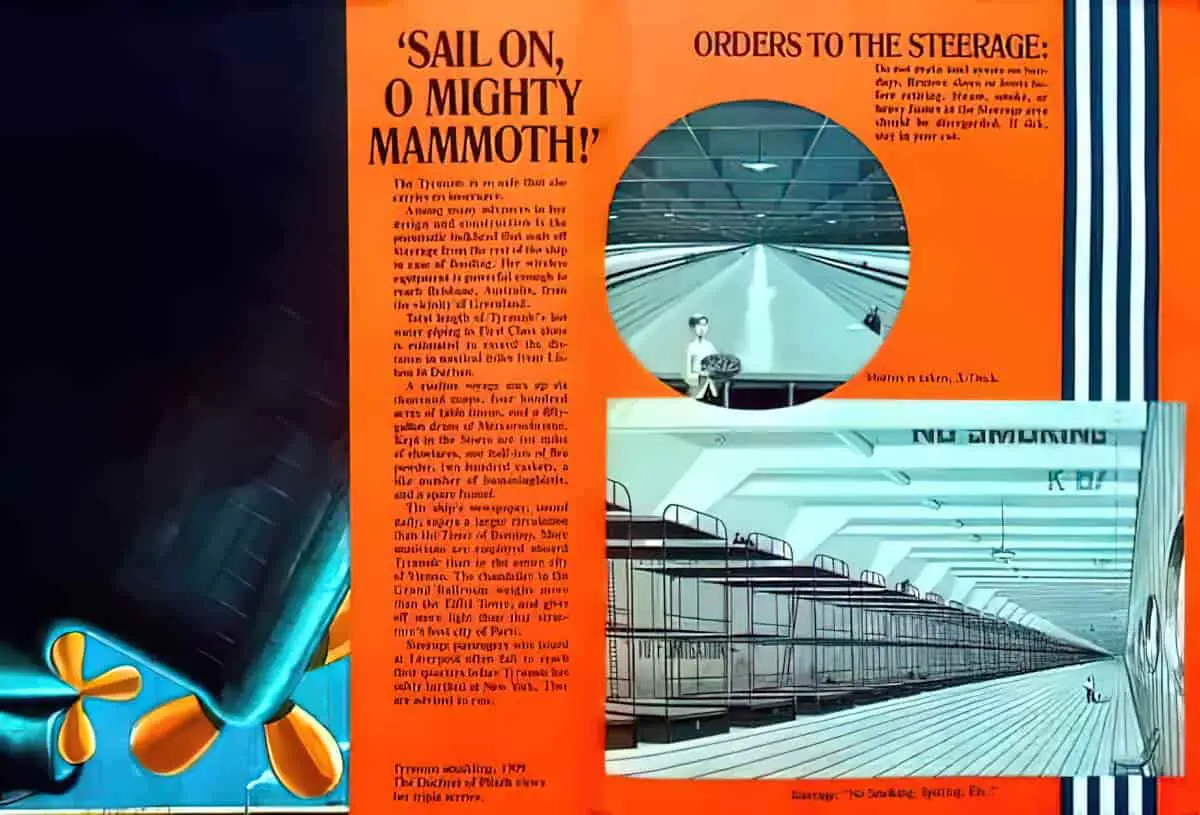

Modern humans are used to seeing massive man-made constructions. Visit any city and skyscrapers no longer excite most of us. But massive ships were once the most enormous man-made constructions people had ever seen. The illustration below, from 1923, makes the most of a ship’s size, which is really only palpable when standing right beside one.

The misconception that massive ships are indestructible came to an end after the tragic sinking of The Titanic.

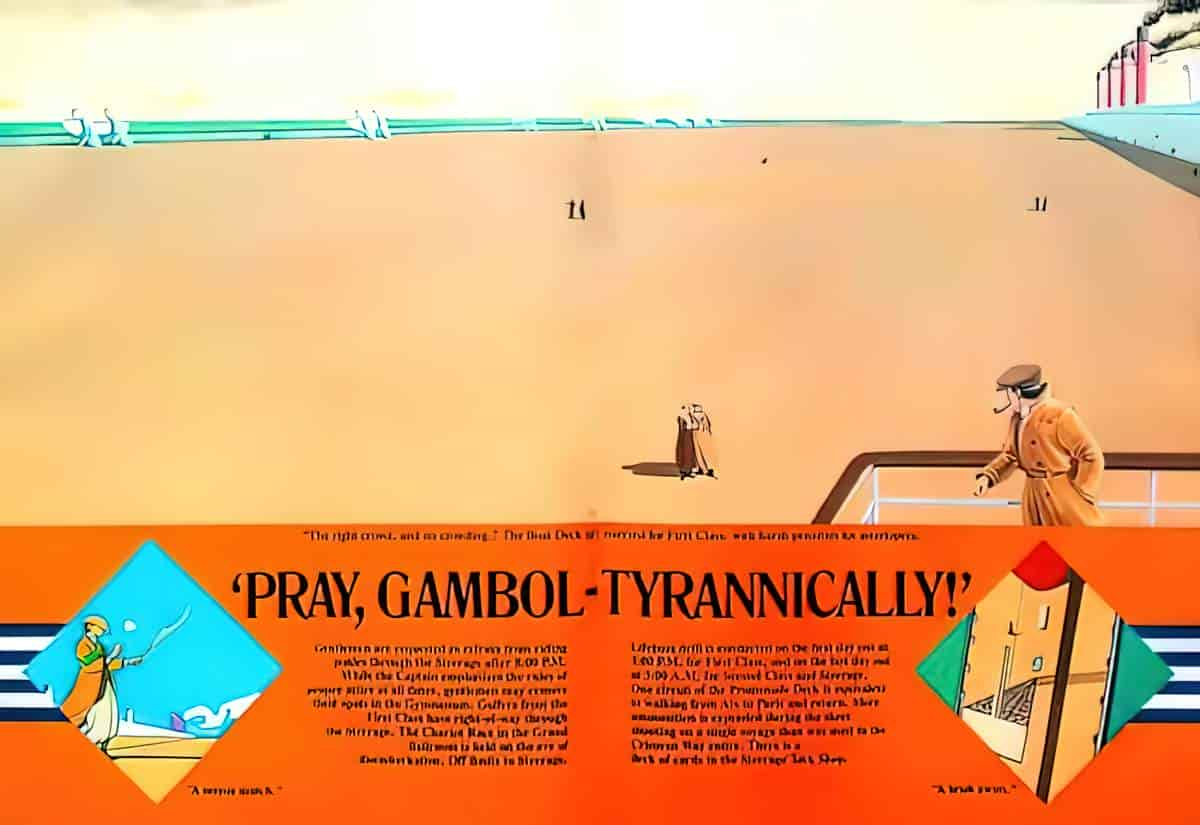

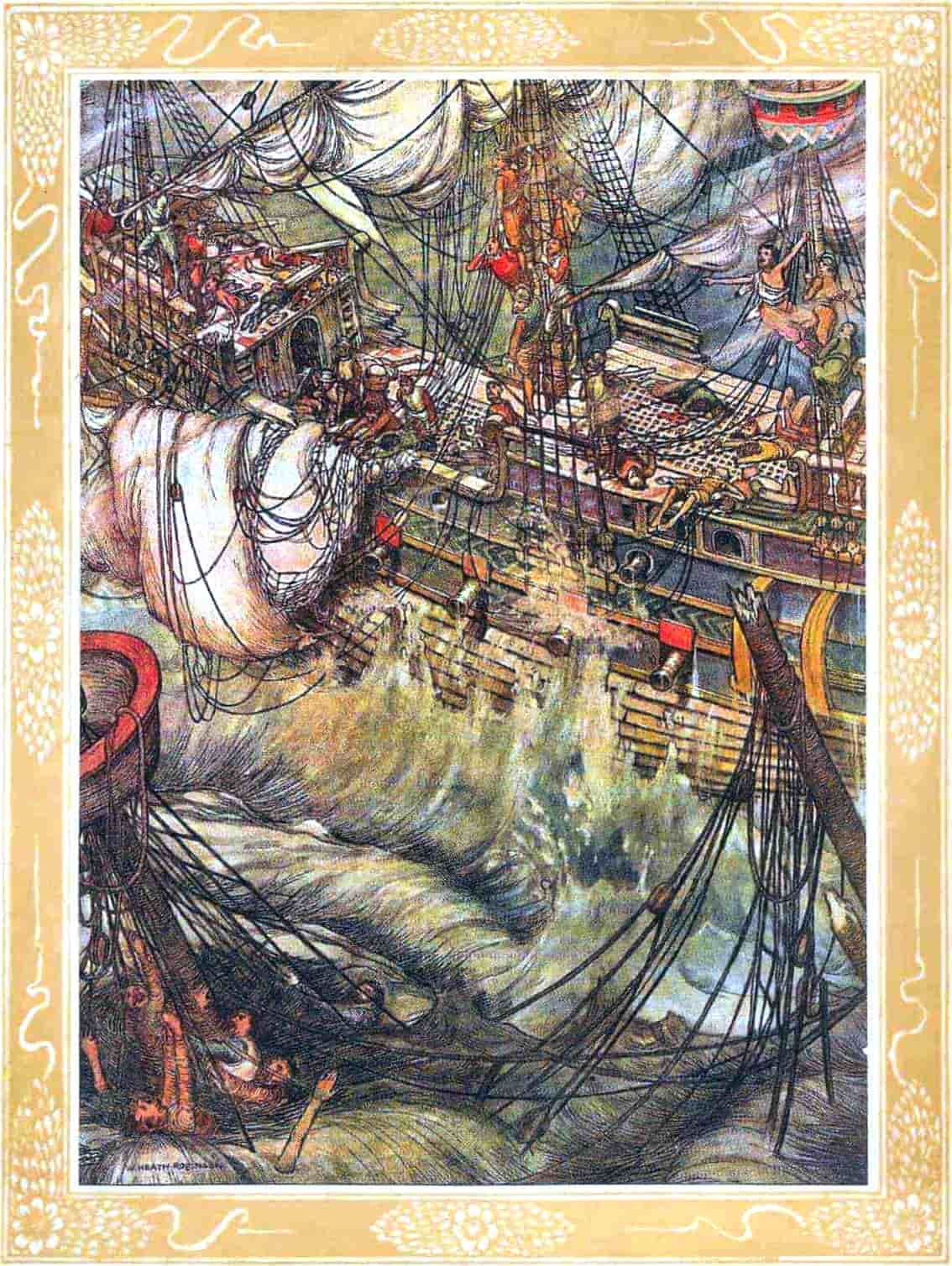

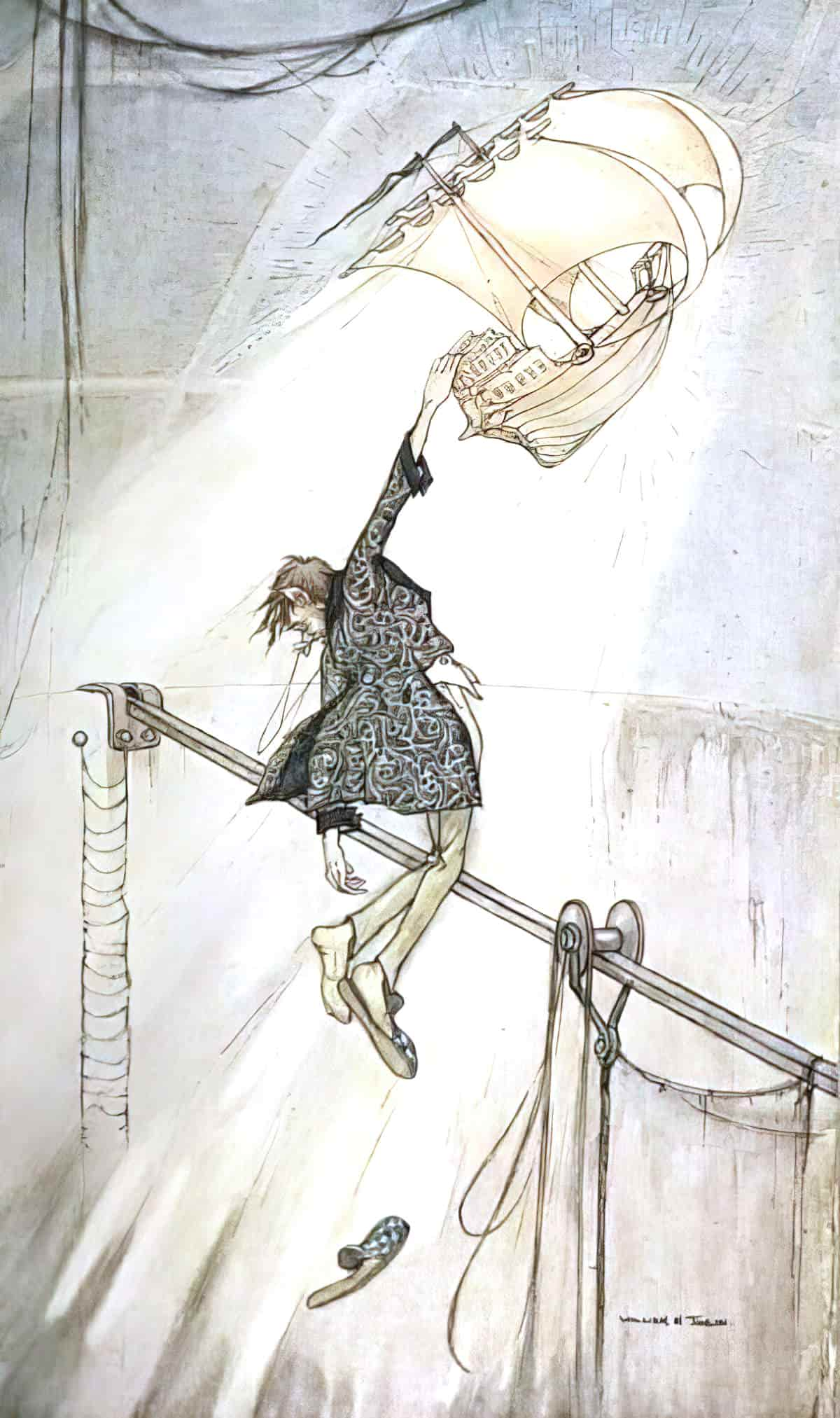

The illustrations below are from Song of the English (1909), a book of jingoistic poetry celebrating British colonialism by Rudyard Kipling. However, the art by W. Heath Robinson beautifully emphasises the massive size of the ship in a top-down then a bottom-up perspective.

Related to this was the idea that ships are feats of human workmanship, proof of our superiority and conquering the world. (The sinking of The Titanic brought us down a peg.)

I grant that ships are impressive, more so 100 years ago.

THE SHIP AS FLOATING MINIATURE CITY

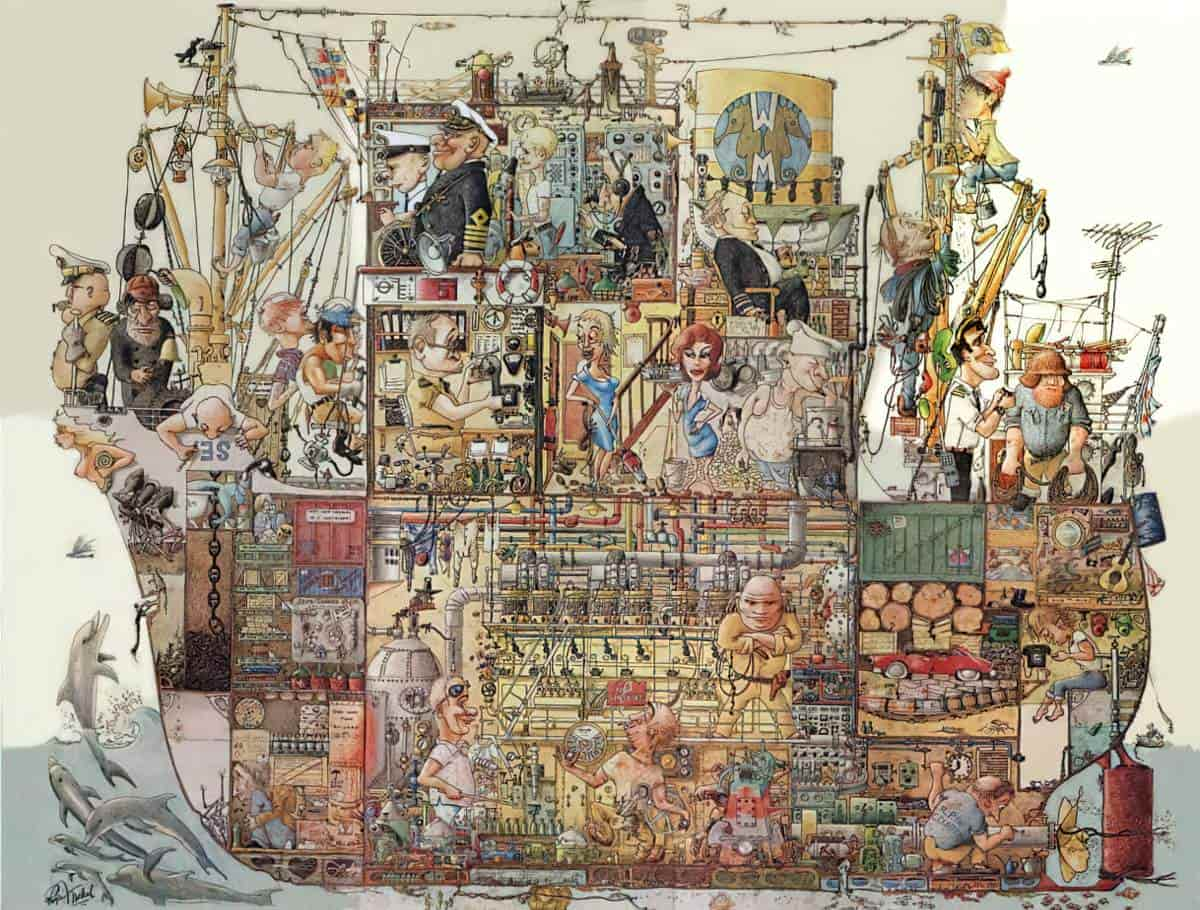

Ships require a diversely skilled team of people in order to work. The cutaway illustration below, by Rogier Mekel in the 1960s, emphasises the hive of activity which takes place on board a ship.

THE CRUISE RENDERED FRIVOLOUS

In her short story “Powers“, main character Nancy becomes an elderly woman. After her husband dies, she goes on a ghastly geriatric cruise at her friends’ behest. In the parts left out of the story, it seems Nancy is done with people telling her not to go deep into her own mind. She has spent her entire life caring for others. Though the sequence on the ferry is summarised rather than shown, Nancy’s experience on the cruise ship seems to have switched something over in her — she will no longer fill up the rest of her life with frivolities that keep her entertained on the surface. Munro may be making full use of the symbolism of the sea, in which the surface is symbolically different from the depths. By dutifully taking a trip on a ferry, this is symbolically the same as avoiding her subconscious, if the ocean depths equal our subconscious.

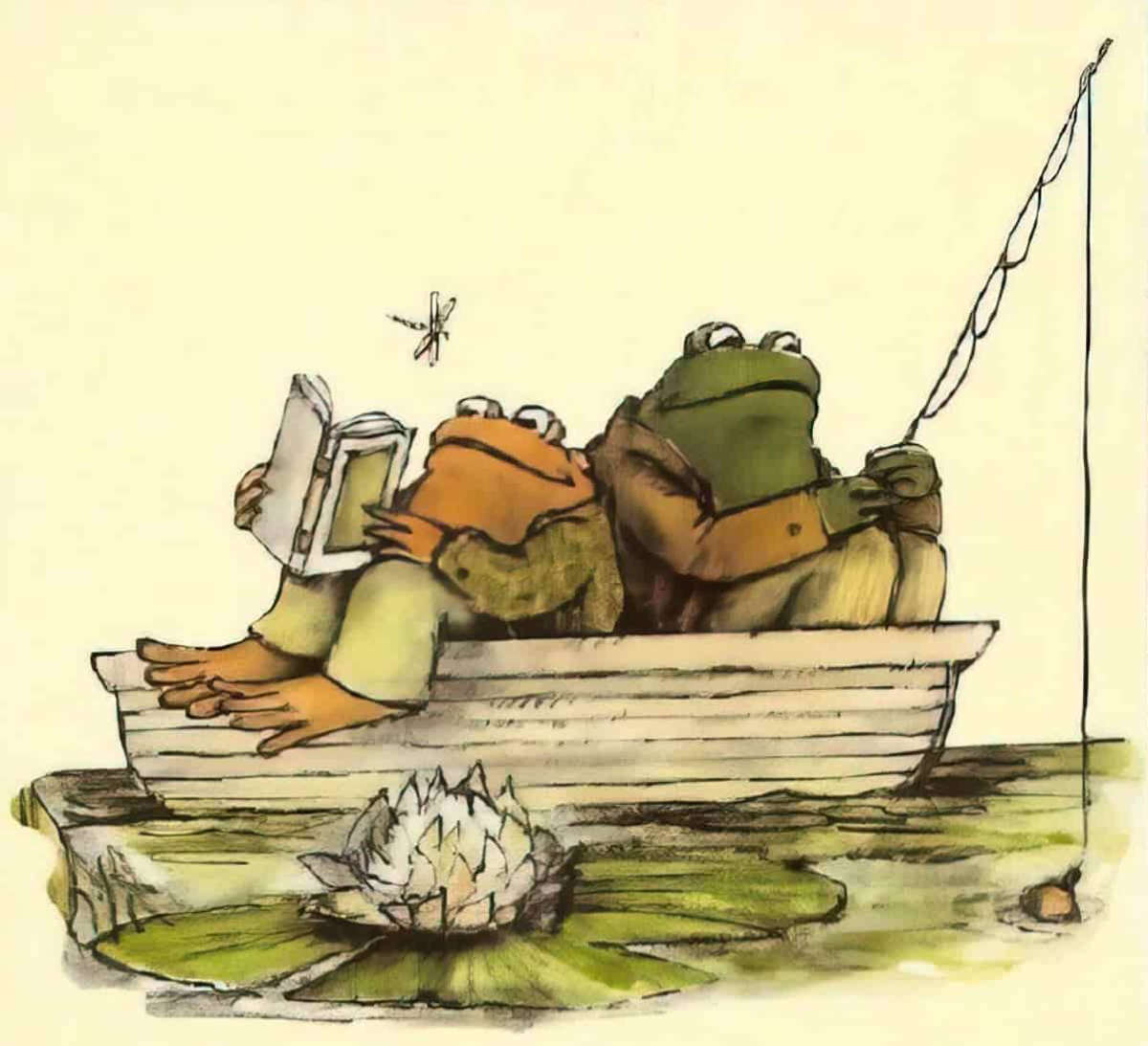

THE RIVER STYX

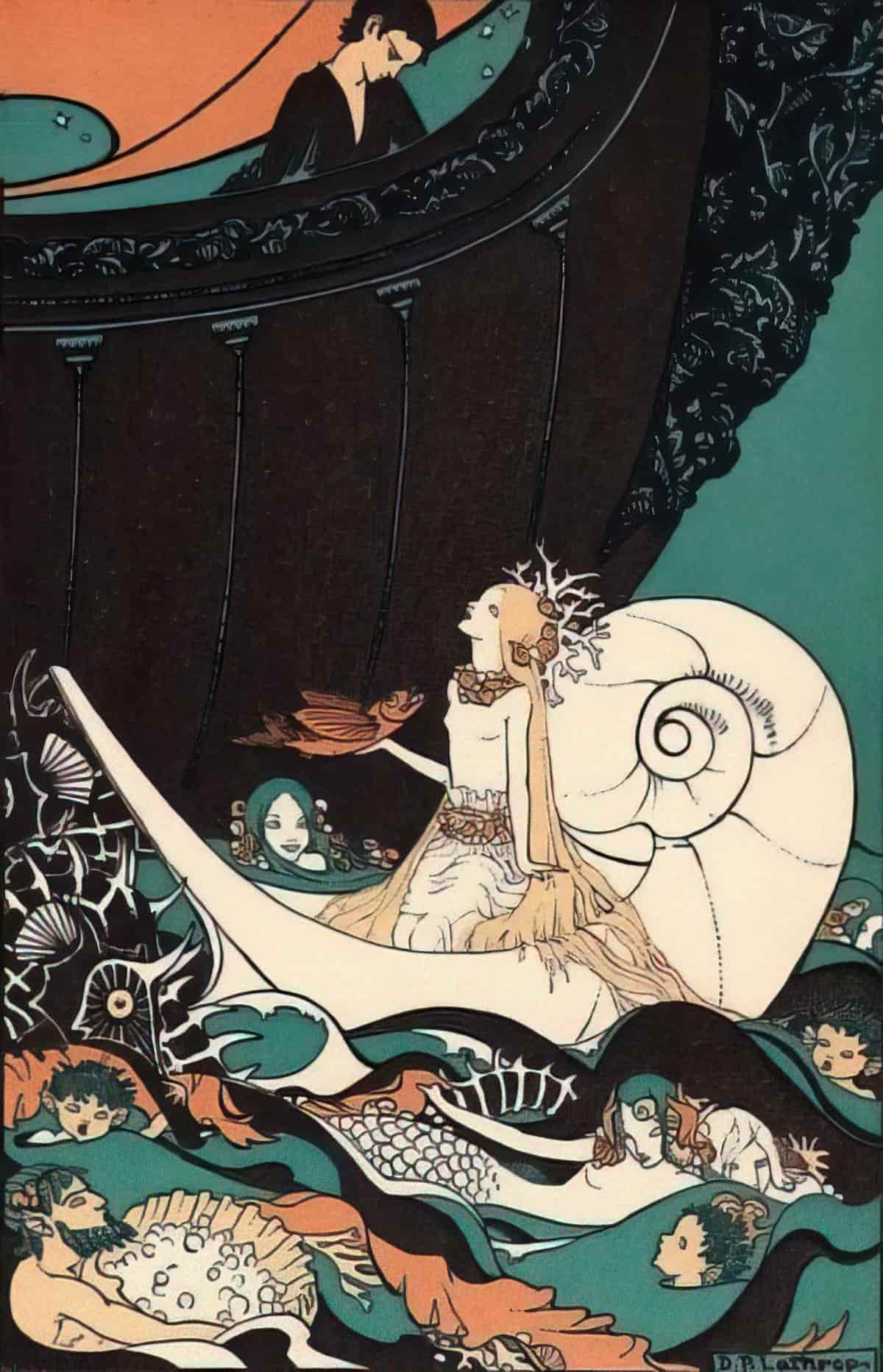

A small boat, a man, a river — this will put you in mind of the River Styx. For more on that see Glossary of the Underworld.

SHIPS AS CHARACTERS, CHARACTERS AS SHIPS

In stories, ships are often treated as characters.

Katherine Mansfield sometimes used ship and boat metaphors to indicate a character’s anagnorisis that their path was set.

In “The Wind Blows”, Katherine Mansfield takes adolescent main character Matilda down to the sea, where she looks out upon the water and sees a coal hulk. This image contrasts with the hormonal turmoil she’s felt all day, exacerbated by the famous Wellington wind. This ship seems to say something about fate — the hulk is a calming anchor in her mind. She imagines herself as the ship, perhaps as a calming strategy, but also as the realisation that her whole life stretches before her, vast as the sea, and despite the ups-and-downs of this particular day, life will go on.

In “Pictures“, ageing singer Ada Moss eventually realises she must engage in sex work to avoid being turfed out of her housing mid-winter. That’s the plot revelation. The revelation is more subtle, symbolised in the final sentences when Ada imagines herself and her customer as yachts.

In another Katherine Mansfield short story, “Je ne parle pas francais“, our unreliable narrator Duquette imagines his friend Dick has ‘been to sea’: “I cannot think why his indolence and dreaminess always gave me the impression he had been to sea. And all his leisurely slow ways seemed to be allowing for the movement of the ship. This impression was so strong that often when we were together and he got up and left a little woman just when she did not expect him to get up and leave her…” Eventually Dick leaves Paris for England. “He put out his hand and stood, lightly swaying upon the step as though the whole hostel were his ship, and the anchor weighed.” The viewpoint character Duquette feels lost without him, but doesn’t have the self-awareness to understand why. Later, when Dick Harmon returns, Duquette imagines him as a steam train rolling into Gare Saint Lazare.

This is a perfect example to make my point: That ships and trains have very similar, overlapping functions in storytelling. The difference is perhaps this: A ship contains an ocean below it, and therefore masks hidden depths. In contrast, readers are not encouraged to ponder the earth below a train (unless the train is underground). Trains keep us imaginatively on level ground. We associate ships with hidden depths and trains with a different type of terror: fatalistic outcomes leading us irrevocably toward death.

THE SAPIENT SHIP

Often a feature of highly symbolic genres such as science fiction and gothic horror stories, the sapient ship has a mind of its own.

BOATS AS FAMILY MEMBERS

Perhaps more than any other kind of vehicle, we like to think of boats as individuals within a family. This might come from the concept of a tug boat perhaps. The small boat has might and pulls the larger boat, which seems like a reversal of the typical parent/child dependency.

The correspondence between the two girls (sisters?) and the boats is clear in Anders Zorn’s painting below.

SHIPS AS ISLANDS

If you go to an island, it seems like there’s no coronavirus. And the boat itself is like an island. You’re separated from the stress of life.

The Boat Business Is Booming, NYT

You can’t keep Huck and Jim on that raft forever, and once they leave it, they must confront the brutalities of society.

Considering The American Voice, NYT

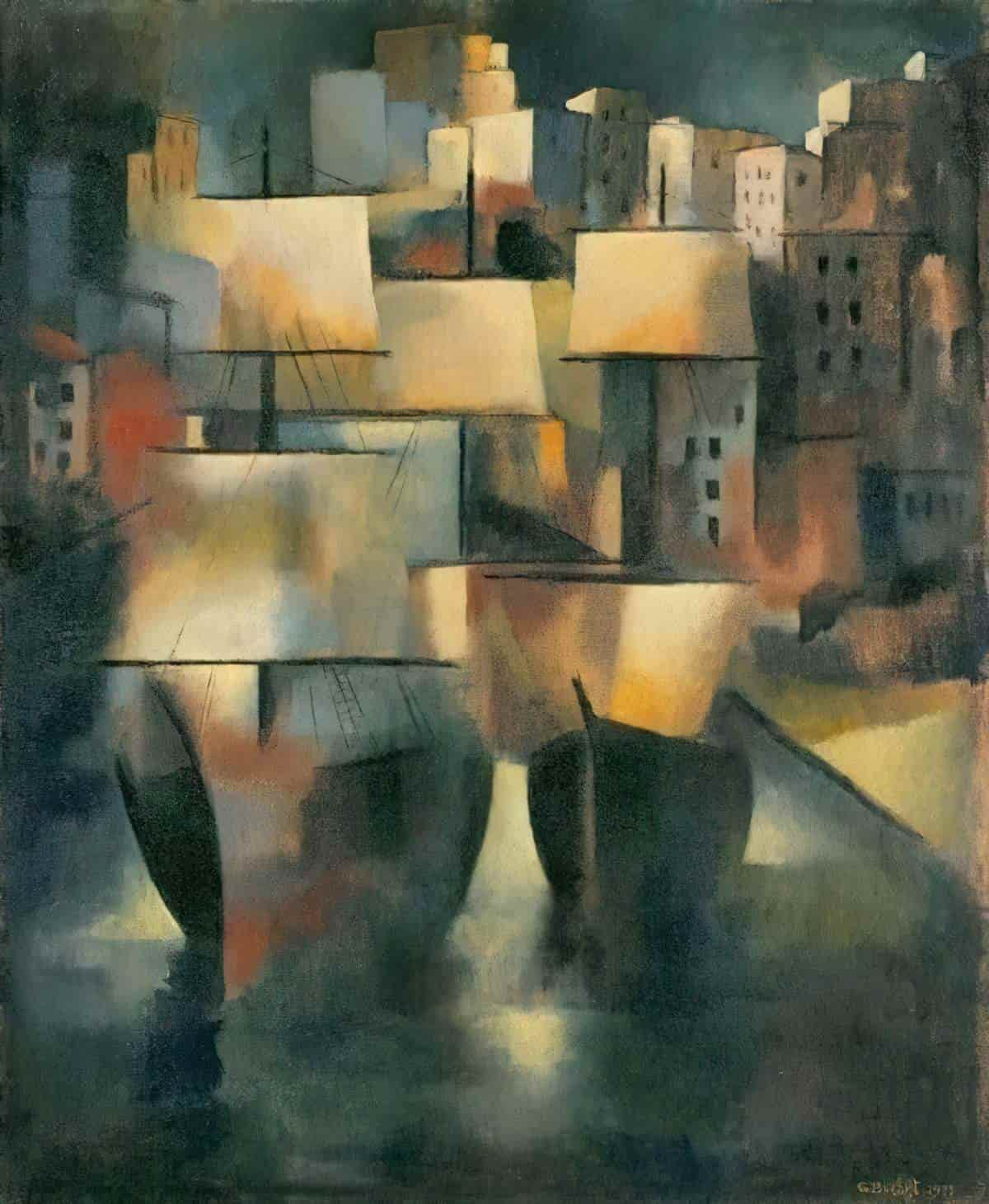

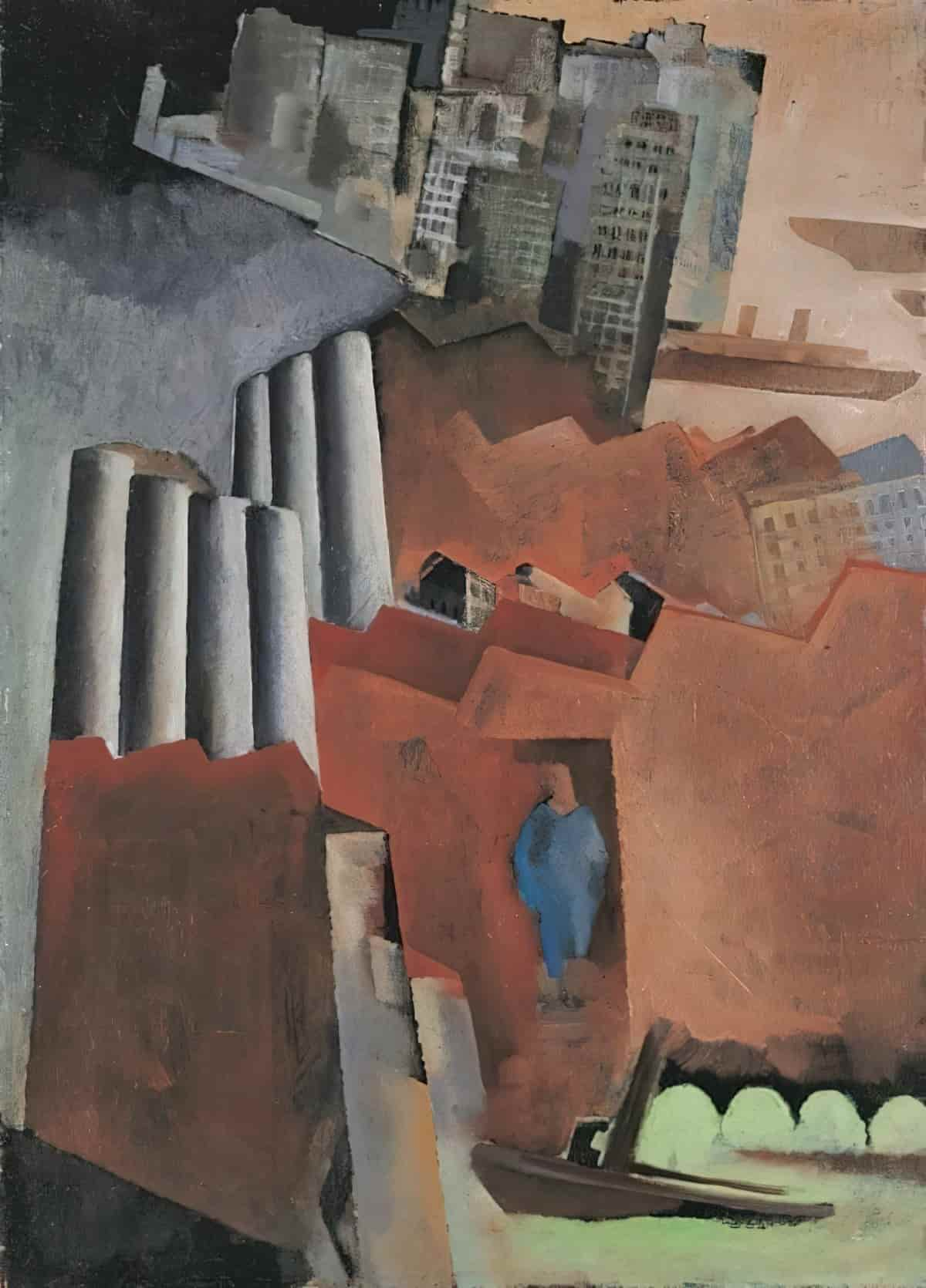

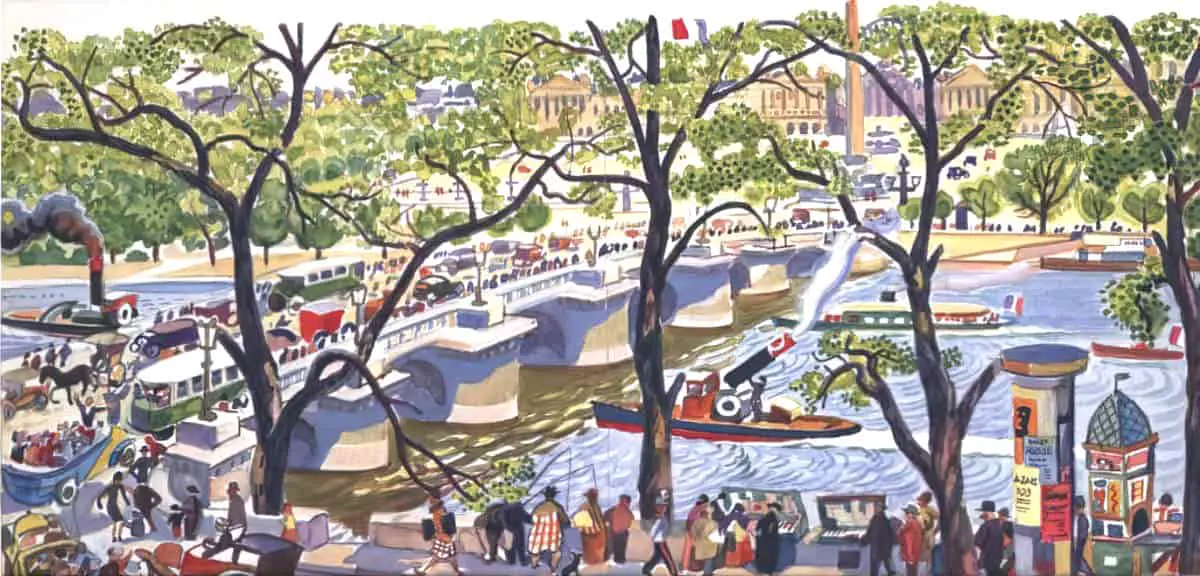

SHIPS AS CITY

In the painting below, the navy ships are painted to blend with the city — where does the city end and the navy begin?

A fleet of ships in the distance vaguely resembles a city, ONLY at sea. This is surely connected to the ‘ocean as city’ aspect of ocean symbolism.

THE LUXURY SHIP

I suspect 2020 will mark a change in public perception of cruise ships, not so much as luxury spaces but as hotspots for pandemic level viruses, but it will be interesting to see how long that lasts.

The modern luxury cruise liner, perfect for spreading disease, is simply a reversion to the historic riskiness of ships. Storms, icebergs, mutiny, starvation, sickness, food poisoning… That’s apart from simply getting lost.

Whenever characters are separated by a ship journey, the audience wonders if loved ones will ever reunite.

BOATS AND SHIPS AS A PLACE TO WOO A WOMAN

Research has shown that when asked on a date from a high and precarious place, the person asked is more likely to say yes. This psychological phenomenon must have been intuited for a long time, I think. Case in point: All the paintings of men wooing women on little boats, which are not especially dangerous in the scheme of things, except you’ve already asked her to trust you completely by taking her into a body of water in a tiny little vessel, and who knows what you plan to do with her there. If she’s not already a tiny little bit scared of you, there’s always a danger of falling in.

These illustrations, both by Harald Skogsberg, show the romance and also the comedic potential of taking a lady out on a boat.

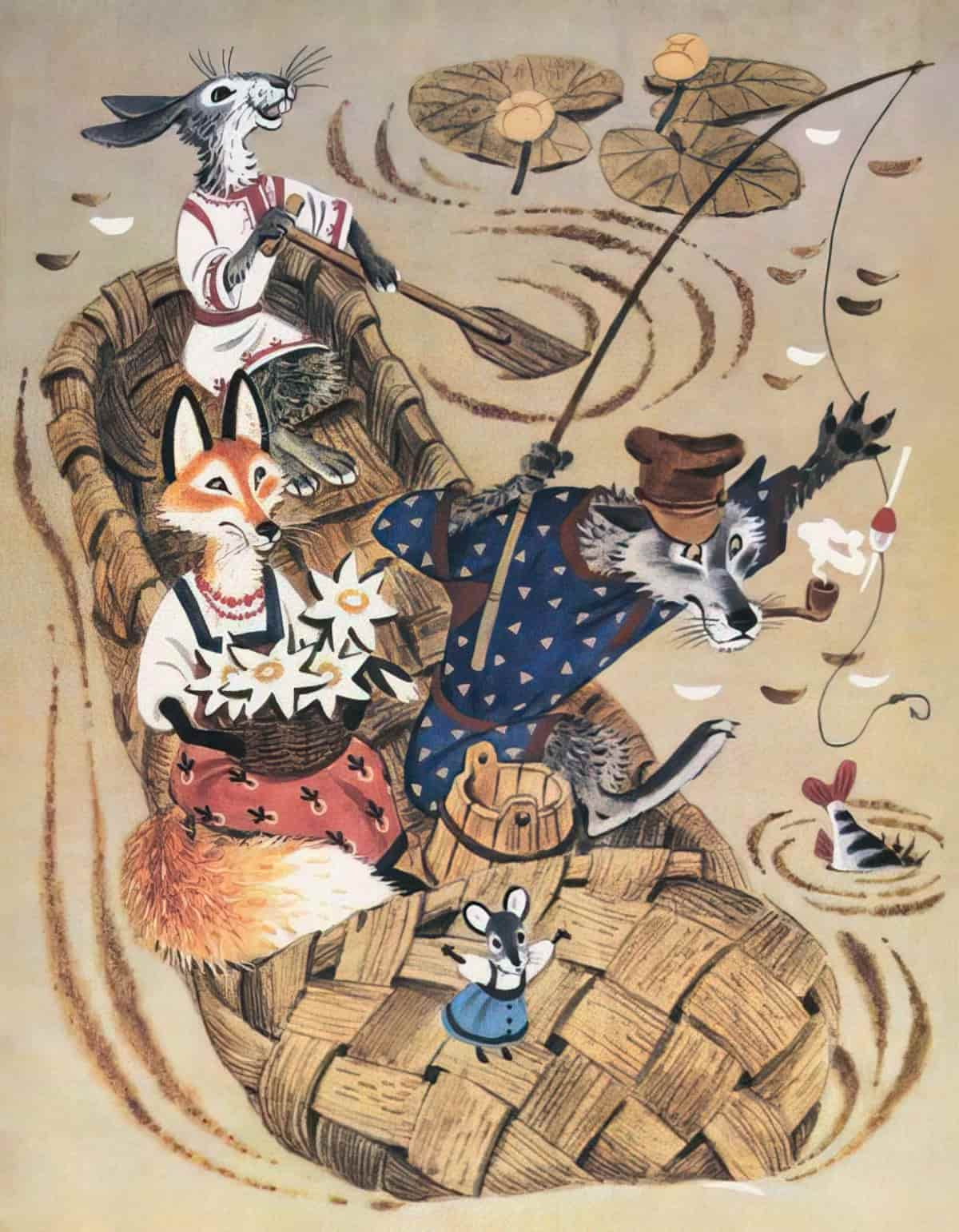

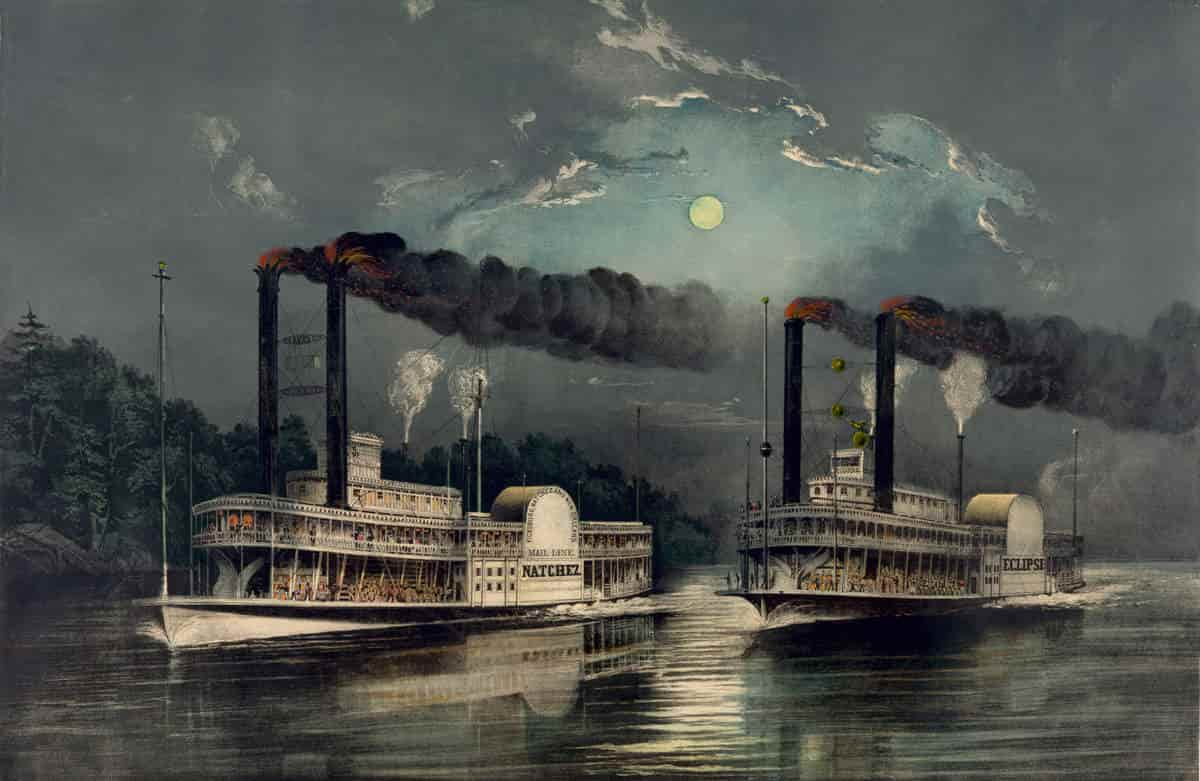

BOATS AS CARNIVALESQUE VENUES

A showboat is a ship or boat that functions as a traveling theatre.

BOATS AS FANTASY PORTALS

Pretty much anything can serve as a fantasy portal — boats and ships are among the less imaginative, I guess. There’s a strong history of boat portals in folklore, for example dead people crossing The River Styx. Likewise, you can take a boat to Fairyland.

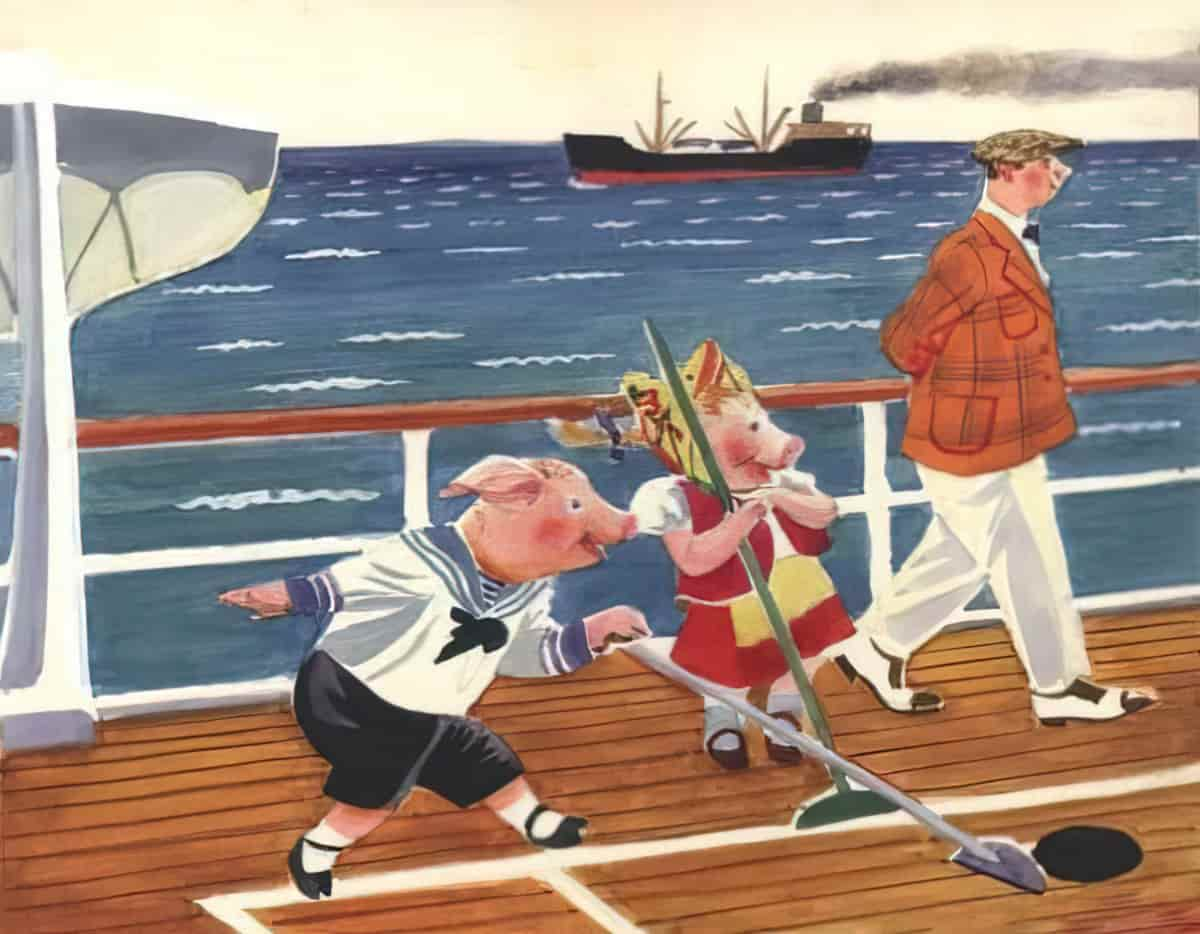

IMAGINATIVE PLAY AND BOATS

‘Boys playing sailors’ is a common trope in stories about children, and is traditionally considered a typically boyish thing to do, along with playing pranks with toads and climbing trees.

FLYING SHIPS

The ability to fly is one of the main wish fulfilment fantasies delivered by fiction and if an object exists in the world, some storyteller somewhere has made it fly. The ship would make an especially good flying vehicle. Unlike, say, a rug, where you have to hold onto the sides for dear life and have no facilities onboard, a ship can house you comfortably as you fly from place to place.

The ‘spaceship’ is of course the epitome of this. The name ‘spaceship’ has a literary quality to it; astronauts and space engineers are likely to use the term ‘spacecraft’ when referring to the real world objects.

“The Ship that Sailed to Mars”, written and illustrated by William Timlin, 1923

MINIATURE SHIPS

Ships help us bridge vast magnitudes inside our imaginations. 150 years ago, to board a ship meant you were undertaking a journey more lengthy than any other available to you on land. It was the only way to get from one hemisphere to the other.

Today the Earth seems small due to aircraft, and the furthest distances covered by man now happen on spaceships.

Wealthy Victorians showed great interest in miniature objects. They created miniature versions of their houses (now sometimes mistaken for doll houses), they kept cabinets of curiosities and they also liked tiny ships. The ship inside a bottle entrances the viewer not just because it has been constructed inside a bottle but because it can be held in the hands.

During the 1880s my ancestors left the United Kingdom on a ship, travelled all the way to New Zealand and never returned, though two generations later, my grandmother still referred to the United Kingdom as ‘home’. She never went further than Australia in her lifetime. Perhaps the intrigue of tiny ships allowed pre-flight, pre-Internet generations to imagine they lived in a smaller world, and to imagine that if they wanted to see their ‘homeland’ or their loved ones again, it might be no more arduous than crossing the living room.

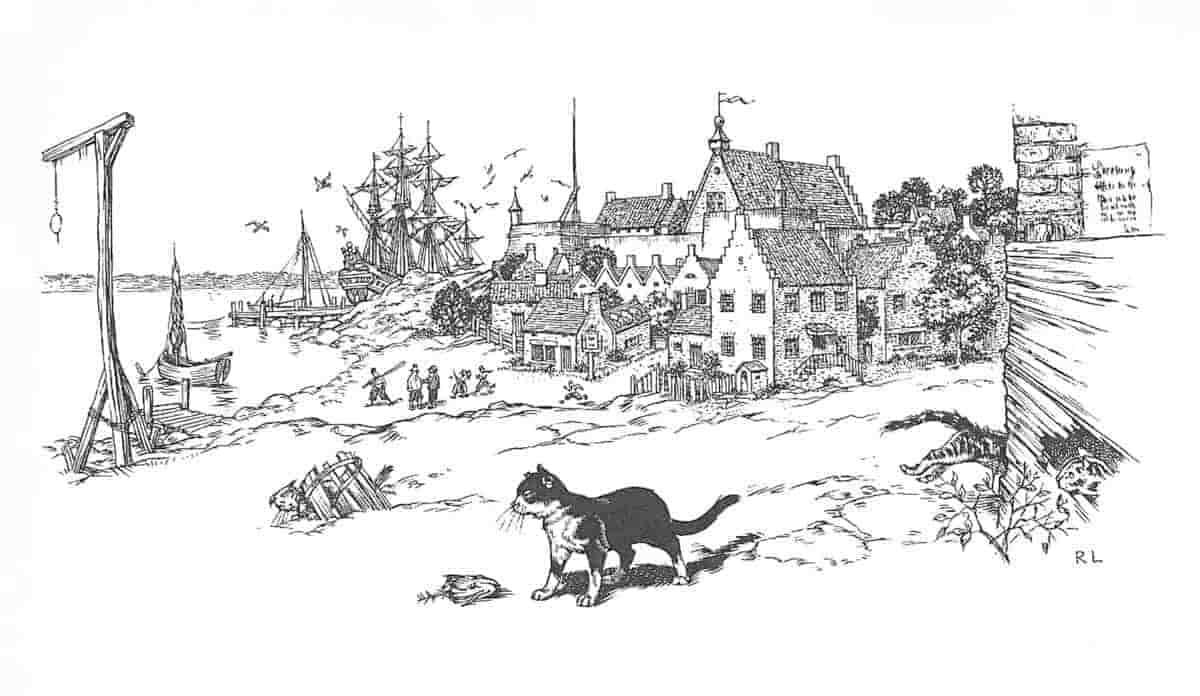

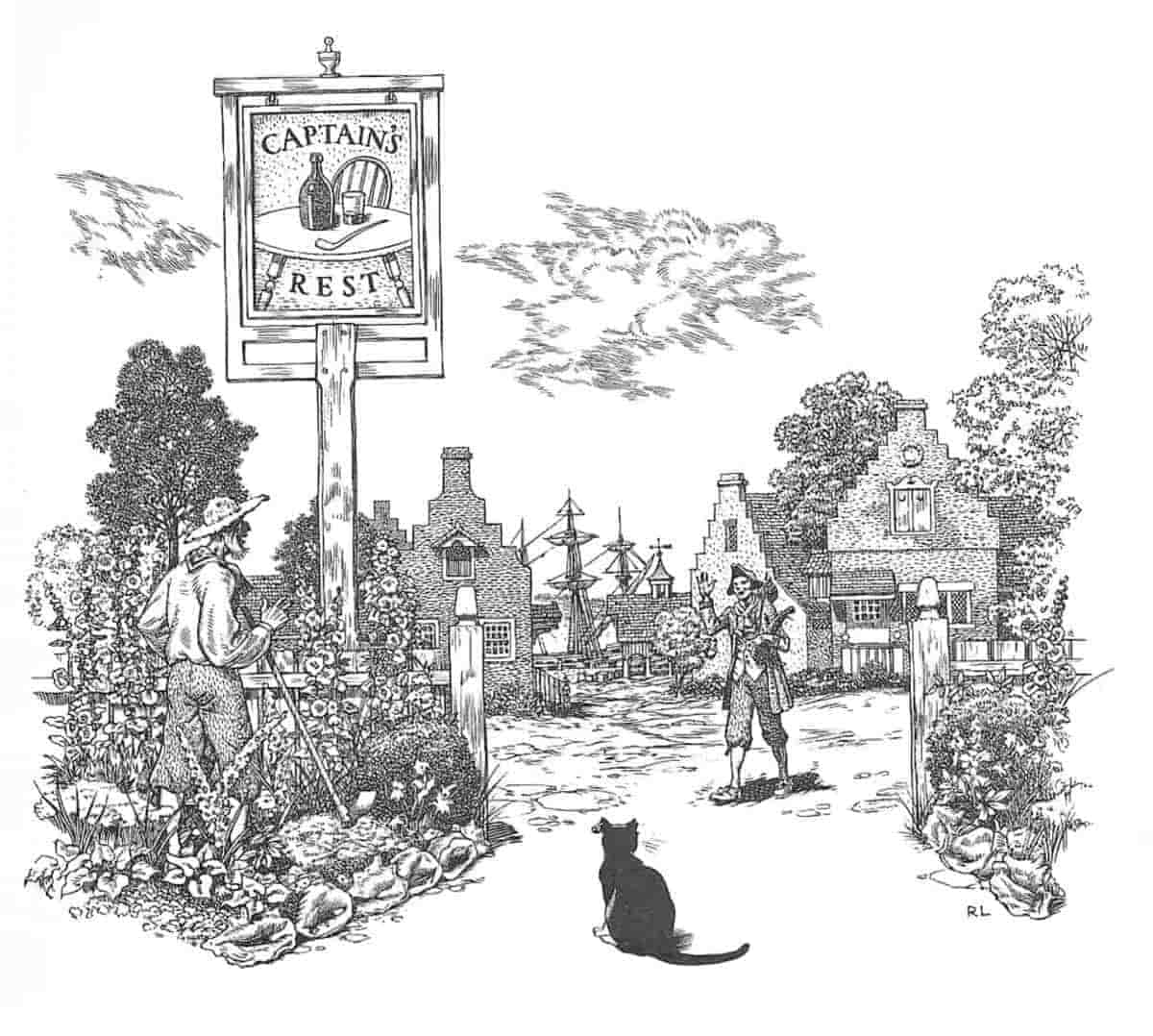

CATS AND RATS

Apart from humans, cats and rats are the mammals we associate with ships.

Cats have been carried on ships for many reasons, most importantly to control rodents. Vermin aboard a ship can cause damage to ropes, woodwork, and more recently, electrical wiring. … Cats naturally attack and kill rodents, and their natural ability to adapt to new surroundings made them suitable for service on a ship.

Ship’s Cat, Wikipedia

PIRATES

The imagined life of pirates is one of glamour, more so than for almost any other criminal. We don’t often glorify burglars in children’s literature, yet empathetic pirates are everywhere. The first decade of the 2000s saw a resurgence in children’s book pirates. See Jack and the Flumflum Tree, for instance. The O.G. pirate story enjoyed by a child audience is of course Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883). Stevenson created a storybook pirate archetype. Children’s authors continue to use the piratical motifs ushered into popularity by Stevenson.

Part of the appeal of the pirate ship must be due to the heterotopia, and the pirate’s status not as an outlaw so much as a renegade who, in common with the contemporary reader, is far less bound by the cultural conventions of yesteryear.

Unlike the rigid rules of Golden Age of landlubber societies, male pirates were marrying other men, for instance. Pirates were renegades in many ways, criminals of course, flat out thieving and terrorising. But their general outcast status allowed them to transcend forward-thinking cultural taboos we are still pushing back against today.

Modern children’s stories are yet to utilise the best anarchist attitudes during the (so-called) Golden Age of Piracy. However, we are recently starting to see some LGBTQ+ pirates. This change is led by storytellers working outside mainstream publishing e.g. funded by Kickstarter. One example is the Promised Land series by Adam Reynolds, Chaze Harris, Christine Luiten and Bo Moore.

TREASURE AT SEA

Modern humans no longer tend to think of ‘treasure’ when we think of the bottom of the sea, but in the ‘golden age of sea disasters’, there was a (fantasy) notion that the seabed was covered in the treasures fallen from sunk ships. The image below is an illustration from a series called City of the Future dating from around 1900. People of an imagined future are looking for treasure on the sea floor.

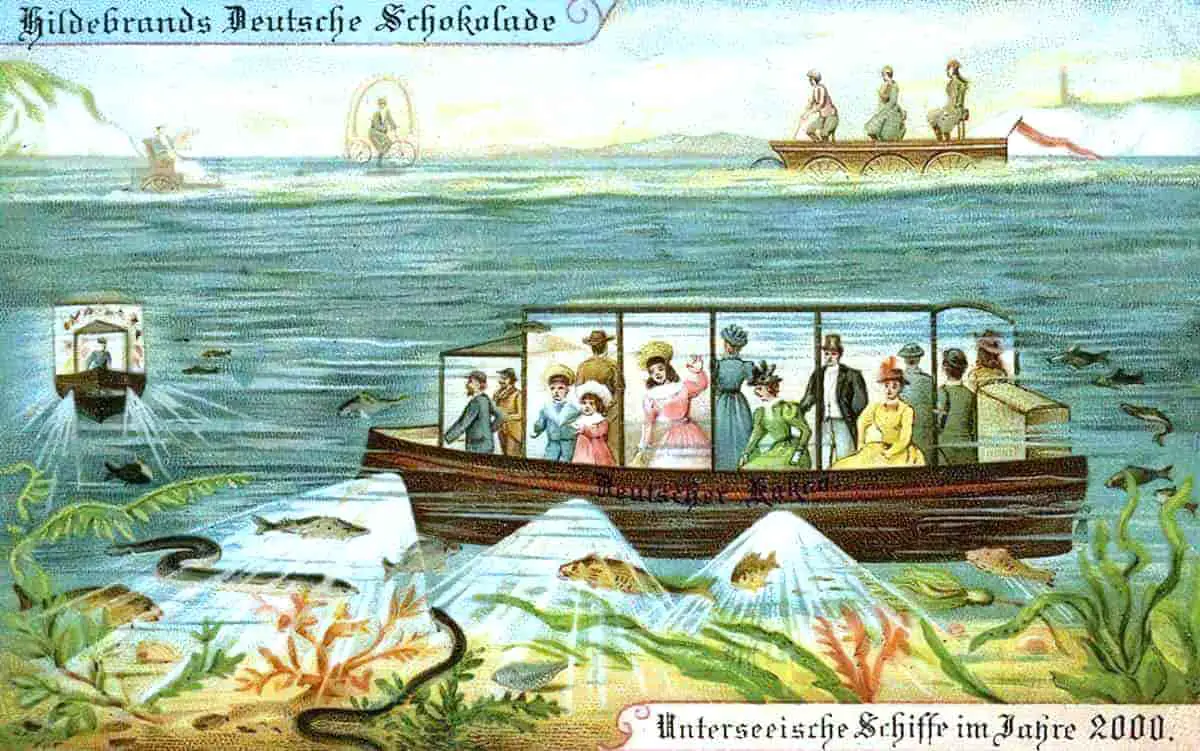

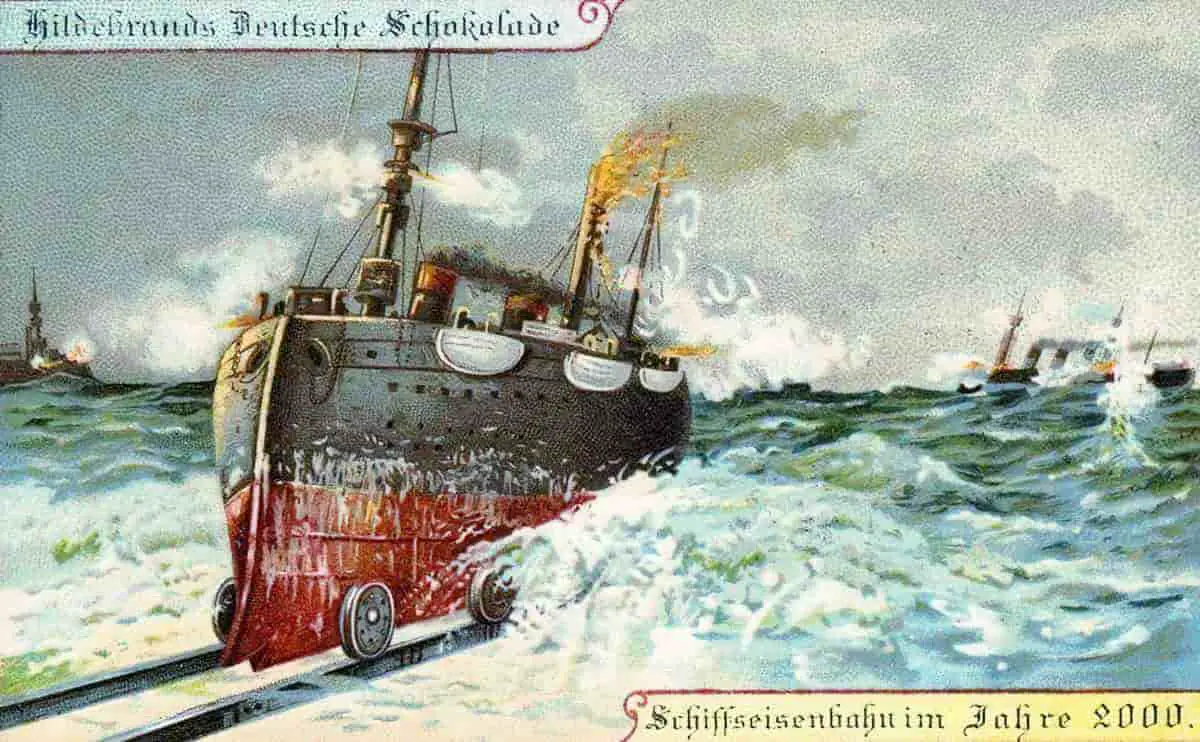

STEAM SHIPS AND SPEED

The image below is something I’ve learned to expect more from illustrations of trains.

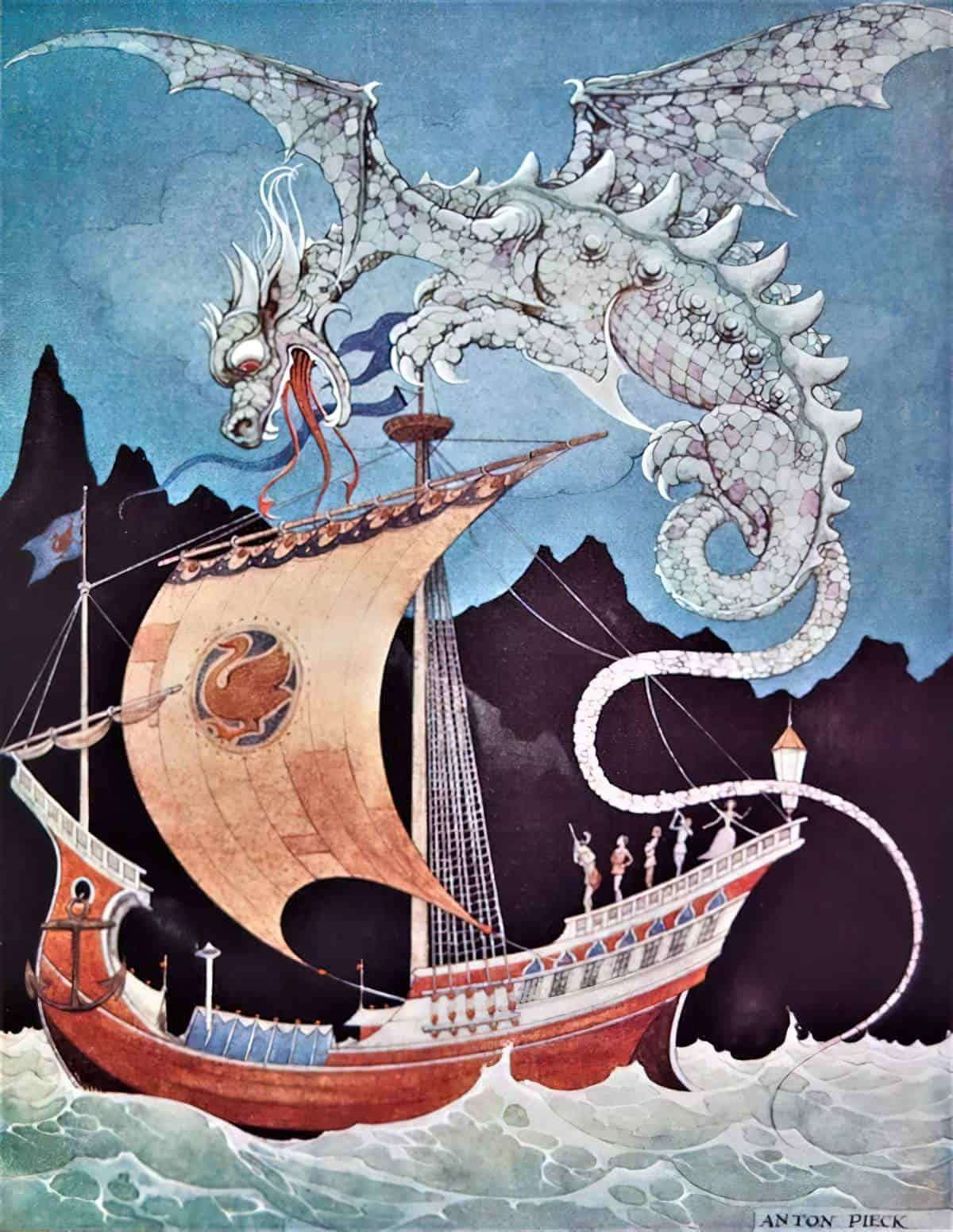

FANTASY ASSAILANTS AT SEA

Because travelling by ship was so hazardous, there are many fantasy creatures imagined as opponents, apart from the sea itself, that is. Evil sirens are one example. Below, it happens to be a dragon.

Header illustration: ‘The Tyger Voyage’ by Richard Adams, illustrated by Nicola Bayley (1976)