Shakespeare wrote Romeo and Juliet in the 1590s. Like modern audiences, Shakespeare’s live audiences already knew the plot because he nicked it from The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (already three decades old at the time). Obviously, when Shakespeare got his paws on plots he elevated them to greatness.

But even before that, stories about young, thwarted (star-crossed) lovers are very old, stretching back into myth. This love story can be seen in the work of Ovid, a Roman poet who lived from 43 BC until 17/18 AD. The real life Ovid was banished by the emperor Augustus to a remote province on the Black Sea, where he remained a decade until his death. (There’s also a banishment plot line in Romeo and Juliet.)

Romeo and Juliet is the ur-Love Story (a.k.a. Towering Love Story) for how we conceptualise young love.

Listen to Romeo and Juliet at Librivox

IS ROMEO AND JULIET COMEDY OR TRAGEDY?

Romeo and Juliet marked a turning point in Shakespeare’s career: a move from history and comedy towards tragedy, although it contains all three. … It proceeds as a comedy might, right up to the deaths of the two star-crossed lovers.

In Our Time podcast

Before writing the play Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare had warmed up by writing the narrative poem “Venus and Adonis”, a big hit. This poem centres female desire. It combines erotic comedy with a (partly) tragic outcome. But Shakespeare had not written tragedy before. Romeo and Juliet was his first.

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is a subversion on the Love At First Sight plot because haste does the characters no good.

WHAT HAPPENS IN ROMEO AND JULIET?

- Setting: Verona, Italy. Elizabethan era. The Duke of Verona is in charge of the city and he’s sick of two rich families who keep fighting. He orders them to keep their brawls off the streets. The families are the Capulets and the Montagues. But it doesn’t help that it’s just a super hot day and everyone’s pretty cranky.

I spent a lot of time over the past year looking at literature on how heat changes the individual and country level propensity for violence. And the short answer is, it goes up. But I don’t think people realize how strong that relationship is. You can even find it in literature. Part of “Romeo and Juliet” takes place on a very hot day, and they know they shouldn’t go out because they’re going to go get into a fight in that kind of heat, but they do it anyway.

But there are all these amazing individual experiments, too. There’s this one sadistic experiment I love where it was in Phoenix, Arizona. And the researchers would get in their car, and they would get to a light. And when it turned green, they just wouldn’t move. And then they would time how long it took the drivers behind them to honk. And the hotter the day, the more the people behind them would honk. The angrier they would get, and they would get angry more quickly. […]

But then you can also find this at the macro level. There’s a relationship between hotter weather and civil conflict. And I’ve often wondered if climate change will kill more people through the wars it indirectly makes likelier than directly through the hurricanes and fires it starts.

Ezra Klein, in interview with Margaret Atwood

- Juliet is a Capulet. (Easy to remember: Her first name and last name pretty much rhyme.)

- Juliet is fourteen years old.

- We don’t know how old Romeo is, exactly. I don’t imagine Romeo as a skinny little guy with years of puberty ahead of him. Because of the sword scene (comign later) I figure he’s got some manly bulk on him, at least sixteen.

- Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet’s families have been at war for so long everyone has forgotten who started it and why. The Montagues are a bit less provocative than the Capulets, who seem to love instigating fights. The Montagues were therefore more likely to produce a kid like Romeo, who isn’t (much) into fighting. His mother is a pacifist — the sort of woman who’d die of a broken heart — which she does — which explains how Romeo turned out like he did. He likes to think he’s non-violent, anyway.

- Juliet’s dad, the OG Capulet, is especially controlling of Juliet because she’s his only daughter. She is carefully watched. But it’s mainly the nanny (nurse) who looks after her, and the nanny probably has this rich interior romantic life of her own, which makes her amenable to

interferinghelping the pretty young thing find love of her own. At least, until it stops becoming a harmless game. - Romeo falls in love with a different girl each week. The latest is Rosaline, who doesn’t like him back.

- Romeo’s friends also despise the Capulets because, you know, solidarity with their rich best friend. But they’re getting sick of Romeo’s love dramas. To stop Romeo going on and on about this Rosaline girl, the three friends decide to gate-crash a Capulet party. Free food and drink! Romeo might even meet a new love interest. Romeo’s still hoping to catch sight of Rosaline. You never know.

- On the way to the party, Romeo’s mates are giving him grief about pining over Rosaline. Mercutio tells him his obsessive love dreams have been caused by the mischief-making English fairy Queen Mab.

- Fortunately this is a masked party, so Romeo Capulet and friends are able to sneak in.

- Still, masks aren’t all that good at hiding someone’s identity. At the party, Romeo’s on the hunt for Rosaline when he spots another pretty girl. His friends’ plan has worked! He’s over Rosaline in an instant. This girl is more beautiful than all the others put together!

- Romeo has no idea that his latest insta-love is Juliet Capulet.

- But right now, bigger problems. He’s been spotted gate-crashing a Capulet party. Juliet’s cousin Tybalt is especially cranky. If the Duke of Verona hadn’t just made each family promise not to murder each other, he totally would have, there and then.

- Instead, Tybalt says, “Watch your back.” There will be time for a sword fight in future.

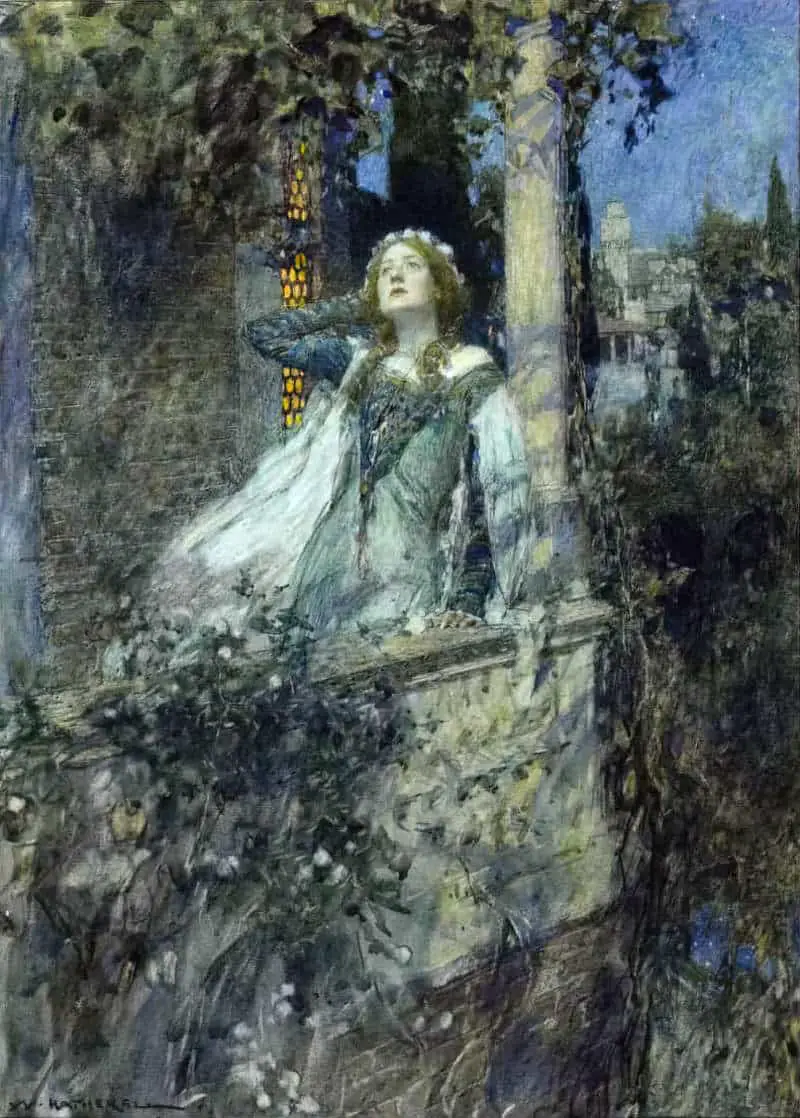

- Romeo leaves the house, but he can’t bring himself to leave the grounds. He can’t bear to be away from Juliet. He waits under her balcony, hoping to steal a glimpse.

- Then something really cool happens. Juliet comes out onto her balcony and starts saying his actual name. Over and over. She’s very clearly smitten with him! “Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”

- Romeo wishes he could be a glove and that Juliet could wear him.

- Like something out of Rapunzel, Romeo scales the house and climbs up to give her a goodnight kiss.

- Juliet suggests they get married the following day. No one needs know about it. Well, except for the Friar, who will be doing the marrying. Oh, and they’ll need a go-between. She’ll get her nanny to do it. The nanny (nurse) is like a mother to her. She’s also a romantic. She’ll be into this.

- Sure enough, the nurse is into it. She helps Juliet meet Romeo at the monastery. Both of them go there for confession anyhow. (It’s surprising they hadn’t run into each other before, really.)

- Despite being a monk, devoting his life in service to God (or perhaps because of it?) the Friar is really into Romeo and Juliet’s love-at-first-sight story. Instead of telling them not to be so naïve, that this can’t possibly be love, he agrees to perform the marriage. The Friar is himself naïve, thinking this might heal the fighting between Montagues and Capulets, which everyone in Verona is totally sick of.

- Romeo is over the moon! We go with him to the market where he’s dancing and on cloud nine. He’s so full of love he only wants to run.

- Wait up. He runs into Tybalt, Juliet’s overprotective cousin who has threatened to kill him. The guy’s not messing around. He’s drawn his sword.

- But Romeo is full up with love and tells Tybalt he doesn’t want to fight, actually. Romeo wants to bring the Capulets and Montagues together. He’s a lover, not a fighter. He doesn’t want his best friend to kill Juliet’s cousin. Romeo falls in love easily — too easily — but the positive flipside of this personality type: He already sees Juliet’s extended relatives as his own extended relatives.

- Tybalt calls Romeo a coward — the go-to insult men give each other to shame them into conformity.

- Romeo’s friend Mercutio turns up. He isn’t in on the marriage plan. “Romeo, are you mad? You have to fight this guy!” Well, if Romeo won’t fight, Mercutio will. He won’t be called a coward, no way. Romeo ducks and dives between them, trying to prevent the fight. Unfortunately, when Romeo is holding his friend’s arm, Tybalt takes the opportunity to lunge forward and kill him. Mercutio dies in Romeo’s arms.

- Okay, now he’s mad. He’ll kill Tybalt for this. So he does.

So now Romeo pulls out the violent tooLkit he learned from growing up in the Mafia, basically. He gets really cranky and kills Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt.

Now he’s done it. The Prince of Verona banishes him. Unlike an exile, banishment is for life. For Elizabethans, this is a fate worse than death. (At least when you die you’re reunited with your dead relatives.)

Ha, banishment? Be merciful, say “death”;

For exile hath more terror in his look,

Much more than death. Do not say “banishment”!

- The city guards are on their way to break up yet another fight. Romeo runs back to the monastery to hide. The Friar passes on news that he’s banished from Verona forever, a fate worse than death. He won’t see Juliet ever again.

- The Friar encourages Romeo to visit Juliet one last time before fleeing.

- He doesn’t know what sort of reaction he’ll get for killing her overprotective cousin. But he gives it a go. He runs into Juliet’s nurse who, unfortunately, had genuine and deep affection for Tybalt. She’s not exactly giving Romeo a warm welcome for killing the guy. But how does Juliet herself feel? The nurse says she’s about as upset over Tybalt’s death as the fact that Romeo killed him.

- Still, Romeo was allowed to spend one last night with Juliet before leaving forever. It was a good night. Juliet was even more into him after that. They decided that Romeo would leave Verona, but Juliet would join him after.

- Romeo is lucky to get away without the parents seeing him. Soon after he leaves, Juliet’s parents turn up. They have plans to cheer her up by introducing her to a potential suitor. They have no idea their young teenage daughter is married already. Oh, and it’s not a date. They’ve arranged Juliet to marry him. The Count of Paris. Wedding date: See you next Thursday.

- Juliet now has something in common with The Frog Princess. For refusing to marry a man she’s never met, she’s called wilful, obstinate and all the other insults people call young women for refusing to submit and comply.

- Like Romeo did when he was escaping the city guards, Juliet also runs to the Friar. What a guy. He comes up with his most ridiculous plan yet. Juliet tells him she’d rather die than marry the Count. Inspired by the word “die”, the Friar suggests she fake her own death. She can drink some kind of anesthetising liquid, but not enough to kill her. Only enough to knock her out so cold everyone thinks she’s dead. Sleeping Beauty/Snow White style. She can lie there and look beautiful and her parents will mourn her death. Her “dead” body will be carried on a bier to the vault in the graveyards where Capulets go to be buried. Once she’s in the vault, the Friar will send for Romeo and they can run off together. No one will think to look for Juliet because everyone thinks she’s tragically dead.

- Juliet is terrified to drink the potion but she sculls it anyway. The wild plan works. Her parents are distraught to find her “dead”.

- Okay this is where the plan goes wrong. The Friar has sent a letter to Romeo, telling him details of the plan and what he has to do. Romeo has gone to Mantua, a town about 35 km away. (Romeo has a horse.)

- The problem: There’s a plague on. The messengers with the letter are detained between Verona and Mantua. They could be carrying germs. They’re not allowed in Mantua.

- But Juliet Capulet is kind of famous — rich, pretty girl — daughter of the main Capulet — and news soon spreads of her death. When Romeo hears of it, he thinks she’s really dead.

- Even though he’s banished, he gallops his horse back to Verona, and goes straight to the Capulet family tomb. (These families know each other really well, don’t they?) Romeo is so distraught he starts to get jealous of the flies, which can at least land on dead Juliet’s mouth and kiss her (etcetera).

- He can’t bear the sight, and drinks proper actual poison, meaning to join her in heaven. He dies.

- Juliet’s potion wears off. Worse wake up scene ever. She realises immediately that Romeo has poisoned himself, thinking his new wife dead. Traumatised, Juliet uses Romeo’s dagger to stab herself. She’d rather have drunk poison, but Romeo didn’t leave her any.

- Having both lost their precious young people, the Montagues and Capulets can now see they have something in common. The Capulets understand what happened, and now they must grieve all over again. They feel they’ve lost Juliet twice over. No one has energy for revenge.

- The Capulet and Montague patriarchs shake hands, each feeling very old now.

- The audience is left to consider how fruitless and arbitrary all this palaver was, and the danger which ensues when young people fall in love too hard and too fast, aided and abetted by well-meaning adults, their freedoms thwarted by other, ill-meaning adults with meaningless vendettas based on nothing more than family name.

FORESHADOWING IN ROMEO AND JULIET

Here’s an interesting concept, which is not foreshadowing but related to it.

HELPING WORK

Diane Purkiss talks about the storytelling technique of “Helping Work” in her book about fairies, Troublesome Things. We find good examples of helping work in Romeo and Juliet.

“Helping work” is a term used by cinema critics to describe when an audience identifies with fictional characters, and wishes characters towards their expected destinations. Even without knowing this particular love story already, an audience comes in knowing Romeo will meet Juliet at the party. As soon as the audience learns of the party, we urge them on to the Capulet mansion. We want to see a group of young men crash a posh party.

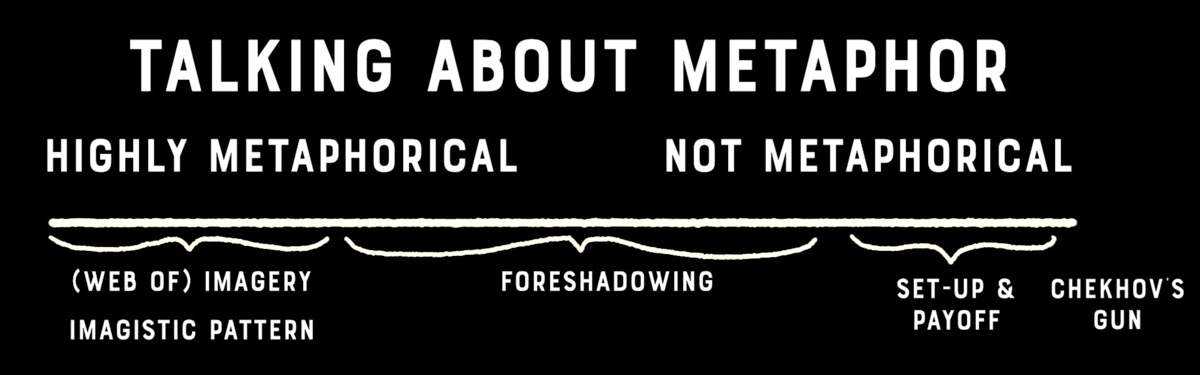

I’ve written at length about the different types of literary shadowing (the most famous being foreshadowing). People mean different things by foreshadowing. To me, true foreshadowing must work at a metaphorical level.

I see Helping Work not as metaphorical, but as a collection of tools from the storytelling toolkit. We might describe Helping Work as a three-pack of tools:

- Signal to your audience what genre to expect (in this case, Love story)

- Make the audience root for your main characters (the love interests)

- Mention an enticing/exciting event due to take place in the near future (the gatecrashing)

Why is it called “Helping Work”? Because if writers use those three tools, an audience will contribute with “Helping Work”.

(I’m yet to find another instance of the use of the term “Helping Work” in the storytelling context. Let me know if you have!)

LETTERS DON’T ALWAYS GO WHERE THEY’RE SUPPOSED TO (plans don’t work)

How did Romeo’s friends know about the party, and who might be there? They intercept a letter. Later, everything will go wrong for Romeo and Juliet when the Friar’s letter never makes it to Mantua.

The audience learns early on, in various subtle ways, that plans tend to go wrong. (This truism does not just hold true for letters.) When the audience realises that the difference between life and death rests upon a single letter, we remember how the first letter never made it to its intended recipient, either.

This, in my opinion, is a metaphorical (true) example of foreshadowing. Foreshadowing works when audiences don’t notice it happening. The link between these two letters happens at a level just below full-realisation of plot, and how things link together.

The emotional valence changes with the letters. That intercepted list of party guests was low stakes. When the Friar’s letter never reaches Romeo, the story has morphed from comedy into tragedy.

“FORESHADOWING” AND DEATH

Shakespeare didn’t like to spring a death on us. He gave plenty of warning. Even today, if a character is going to die at the end, storytellers send hints.

Romeo and Juliet goes further than ‘hints’. Shakespeare tells us straight up in the actual prologue that the young lovers will die at the end:

A pair of star-crossed lovers…Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife

And we’re not allowed to forget it:

- Nurse goes on about how Juliet almost died as a little kid (she’s still a kid, to be honest)

- Romeo senses that gate-crashing a Capulet party will lead to untimely death

- Both Romeo and Juliet threaten suicide when talking to the Friar

Is it ‘foreshadowing’ if we already know they’re going to die? To me, this is simply ‘parts of a story fitting together,’ creating a cohesive story experience for the audience. When we remember their lives are cut short, moments together have more resonance.

WHY THE LONG SPEECH IN ROMEO AND JULIET?

But before the characters get to the party, the audience must sit through an extended speech about a fairy (Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech). Why make an audience endure this? There must be very good reason.

Shakespeare gave audiences two speeches about fairies. The other was in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But there were many, many speeches. Whenever Shakespeare makes a character give a speech, this slows the pacing right down to a ‘pause’ (see: talking about story pacing). The audience catches their breath.

Shakespeare is using a fairy speech in the exact same way in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Why? Purkiss shares the following theory: Both speeches happen during exciting moments. By interrupting this scene with a speech, Shakespeare is balancing the ‘the delicate ground between comedy and tragedy’. Both speeches function as turning points, at which point the emotional valence changes: One turns festive, the other tragic.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN JULIET AND HER NURSE: UPPER CLASS CAGE VS WORKING CLASS FREEDOM

The categories into which history is usually divided — periods like the Renaissance or the Enlightenment — hold little relevance to women’s history. Although shifts in power arrangements or in attitudes do affect women, their condition is most vulnerable to changes in social structures, such as transitions from aristocratic to middle-class or from feudal to bourgeois rule. Most important has been the shift from production in the home to factory labor — the Industrial Revolution.

Poor women are for the most part missing from this account, just as they are missing (along with poor men) from history, but it should be remembered throughout that poor women were personally freer than women of the propertied classes. The latter, seen as property themselves, have been jealously guarded and transferred like property. They had greater ease but less freedom than poor women, who could walk around in the world at will if not in safety, who controlled their own sexuality and their children more than propertied women, and who sometimes controlled even their own little businesses. Poor women were also, of course, freer to starved, to work like beasts of burden, and to suffer from random male abuse and violence. For an example of all this, consider Juliet and her nurse in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet; the nurse is Juliet’s social inferior, but she can go out freely and so can deliver messages for her mistress. As she does so, early in the play, she is verbally assaulted by two young ‘gentlemen,’ even though she is accompanied by her manservant. Being neither clever nor tough, the nurse is affronted. An actual street woman would probably be both, but there is no guarantee that assaults aimed at her would remain purely verbal. Women of the propertied classes were protected from random abuse, but they probably suffered as much as poor women from violence, imprisonment, and murder by men of their own households.

Beyond Power: On Women, Men & Morals by Marilyn French

THE ROLE OF FAIRIES: COMPARING MAB AND PUCK

Queen Mab is the fairy in Romeo and Juliet, mentioned in Mercutio’s speech. She’s a fairy from English folklore. She’s not evil but she does like making mischief.

The beginning and ending of Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech:

O, then, I see Queen Mab hath been with you.

Mercutio is basically describing crushes and the trouble they cause people. His story about Queen Mab and her mischief making is extremely detailed. He’s given this a lot of thought!

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate-stone

On the fore-finger of an alderman.

This is the hag, when maids lie on their backs,

That presses them and learns them first to bear,

Making them women of good carriage.

Puck is the fairy from A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

- Both fairies make mischief.

- They both, in the words of Diane Purkiss, reflect ‘the desires of others in a distorting fairground mirror’.

- Both are related to Cupid (Roman god of erotic love), but in different ways. Mab is Cupid’s way out of Romeo and Juliet. Puck is Cupid’s way in to A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

- Before Mab’s entry: “We’ll have no Cupid hoodwinked with a scarf’. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Oberon asks Puck to play Cupid. Puck’s Merry Prankster stuff functions as ‘a symbol for the comic arbitrariness of desire, which interrupts ‘the saddest tale’ (Diane Purkiss).’

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, everyone is inside the dream, which allows the audience to be outside it. We are shown its workings in Puck-Cupid. In Romeo and Juliet, only Mercutio is outside the dream; only he knows how it works. And paradoxically, that is fatal knowledge, because it is knowledge of the wrong kind. Like Lady Macbeth, like Richard III, he is caught in the wrong play, and he dies for it, giving birth through comedy to tragedy.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things

HOW DOES SHAKESPEARE PRESENT LOVE IN ROMEO AND JULIET?

Ever known one of those guys who falls in love every week?

How about this guy from reality TV series Below Deck? Kyle suffers from a form of object impermanence, but for girlfriends. (Object impermanence: Out of sight, out of mind.)

“men don’t do drama” Romeo literally married a girl he had known for three days and then murdered her cousin

Owl! at the Library (@SketchesbyBoze)

Passion is passion is passion, and Romeo can flip the switch from ‘horny’ to ‘murderous’.

IS IT LOVE OR A CRUSH?

Romeo is moping around because he’s in love with a girl called Rosaline, who doesn’t love him back. (We never get to meet Rosaline. Methinks she knows he’s a player and can’t be dealing with his crap.)

Romeo is literally looking for Rosaline when his eyes settle upon Juliet Capulet. Immediately, Juliet is his new crush.

Likewise, Juliet wants to marry Romeo. That’s all the pair really want, along with adult levels of freedom, since both come from super wealthy families and can’t possibly want for much in the material sense.

Doesn’t really matter, because the story outcome would be the same. I think this question is complicated, because you can absolutely fall in love with an imaginary version of a real person.

Crushes are rooted in fantasy and tend to happen when you don’t know much about a person but idealize what they are like. Crushes and love do, however, have biological similarities. Hormones like dopamine and oxytocin release during both experiences.

This Is Why You Develop Crushes, According To Science

Clearly, Romeo doesn’t know Juliet well enough to love Juliet for herself, but I believe people quite capable of falling in genuine love with the rounded-out versions of people they don’t know at all. Hormones and horniness (lust) is the mechanism which drives this phenomenon.

That said, it makes complete sense that Romeo and Juliet would fall in actual love (not just lust) because their backgrounds are very similar.

FILM ADAPTATIONS

Opinions vary on various contemporary film adaptations.

ROMEO AND JULIET (1978 FILM)

Not a great adaptation of not a great Shakespeare play. As a love story, it’s pretty awful, using and to some extent codifying some of the worst tropes in romantic fiction. However, as a cautionary tale about the dangers of hatred, it tells a genuinely compelling story.

Ace Film Review of the 1978 film adaptation

ROMEO + JULIET (1996 FILM)

Shakespearean experts disagree about the Baz Lurhmann film, but one thing’s for sure and certain: It’s divisive!

INDIFFERENCE TO DEATH

Baz Luhrmann’s much-hyped film of Romeo and Juliet is a dazzling piece of cinema that deliberately shuts its eyes to the play. The ho-hum gangland scenario – de rigueur for the feud since Bernstein’s West Side Story – is the beef here. The point is that it renders life and death not tragic, but arbitrary. No one here knows how the dream works, because it has no works, only random lurches.

This cannot help but make the audience indifferent to every death

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things

except those of the lovers, and in this case even those of the lovers are

so rubbed smooth by repetition, so worn by meeja overhype, that they wring are themselves second-hand.

However, Diane Purkiss does see the reason for the street drugs.

TREATMENT OF DREAM VIA DRUG HALLUCINATION

Before making the Queen Mab speech, Luhrmann’s Mercutio, himself a drag queen, holds in his hand a blandly smiling tab of E. Now, in one sense this is drably literal; gee, bet those people in the past who saw fairies were all on something, yeah? But the drug is an apt metaphor for the power of speech in Renaissance times; like E, rhetoric was seen as subversive, too much fun, and likely to persuade people to do Bad Things. In another sense it marks the difference between Shakespeare’s Mercutio and Luhrmann’s; Shakespeare’s could be drunk on words, but Luhrmann’s needs a chemical to be high enough to see a fairy who isn’t there.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things

Emma Smith (at 12:5 , after analysis of 10 Things I Hate About You and The Tempest), Professor at Oxford and author of This Is Shakespeare has a different take:

WELL-CHOSEN SOUNDTRACKS CAN COMPENSATE FOR DIALOGUE

I love this movie. One of the best things about it is the soundtrack and if you’re this kind of geeky person, writing a soundtrack — a kind of playlist — for your Shakespeare play is a great thing to do, thinking what songs you’d put, by who, and at what points. How would you do it? You can almost do a play completely as a musical. You don’t really need any of the language. You could just move the tone along.

Emma Smith, Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Hertford College, University of Oxford

WHY DID SHAKESPEARE MAKE JULIET SO YOUNG?

In the play Shakespeare nicked the plot from, Juliet is about sixteen. But Shakespeare clearly made an active decision to lower her age. We can make educated guesses about why he did this. Emma Smith offers some insight:

When Romeo and Juliet first meet, the tropical fish and the music slow the pacing right down.

[The meet cute scene] slows right down. This is important because, in the play itself, everything goes too quickly. Even the chorus starts by saying this is going to take two hours, “the two hours traffic of our stage”. It can’t possibly have taken that, but it gives you a kind of anxious, ooh, everything’s kind of a little bit stressful, a little bit adrenaline-y, a little bit too quick. And the plot is all about being too quick. Juliet is too young to be in this marriage and in this kind of sexual relationship. Fourteen would have been thought to be much much much too young by Elizabethan audiences, just as we think so now. No actor who was fourteen could possibly play this role in the modern cinema. And in fact, I think Luhrmann did try and cast somebody of the age of Juliet and realised after, that was just not going to work.

Next, Emma Smith analyses the masked party scene.

THE MEANINGS OF THE COSTUMES

Poor Paris never got the memo that if you go to a fancy dress party you have to wear a sexy costume. [He’s wearing an astronaut costume.] I mean, he is like a sort of space cadet. He is a kinda spaced out, kind nice, cheesy kind of a guy. He’s like the best friend. He’s never going to be the boyfriend. But the costumes are really fun in this whole sequence — the wonderful drag costume for Mercutio, Lady Capulet’s Cleopatra costume, which is really great on her — kind of a sexy vibe she’s got going. Then you can see the way the lovers are characterised in these fairy tale costumes. She’s an angel, he’s a knight. This is a world of chivalry and the past, and of the storybook. They’re operating in this much more knowing, much more sexualized world all around them and then their costumes and that moment on either side of the fish tank creates a completely different space. They’re like in a different world. Literally, they’re in a world of themselves, but their costumes and everything about that identifies them as a unit against everybody else.

Emma Smith

PACING PAUSE OF THE MEET CUTE FISH TANK SCENE

[Lurhmann needed] to slow this down here, I think, [for audiences] to believe in the romance. Perhaps this great towering icon of romantic love, “Romeo and Juliet” is maybe not all it’s cracked up to be. They’re kids, it happens really quickly, Romeo has hardly finished moping about being madly in love with some other person — Rosaline — who we never see. So Romeo is a serial crush(er) actually. He has these women that he’s — at a distance — absolutely in love with. So maybe the play itself is not quite so clear that this is The Towering Love Story. This is actually young people tumbling into things too quickly under the pressure of their families and that makes them act rashly. It makes them act in ways which are immediately destructive.

But what we’re getting [in the meet cute scene of Romeo + Juliet] is something which gives us a little bit more time on the relationship, which makes it look as if there’s time for this couple to try and get to know each other, even though there isn’t really time. [The movie] gives us the illusion that there’s something a little bit more leisurely, a little bit more considered, and maybe therefore a little bit more authentic about the relationship.

Emma Smith

VASTLY REDUCED DIALOGUE IN SHAKESPEAREAN FILM ADAPTATIONS

(And a tip for reading Shakespearean speeches.)

Most movies of Shakespeare cut an enormous amount of the dialogue, probably between 60 and 80 per cent. Luhrmann’s film cuts about 75 per cent. It cuts really cleverly. [This film adaptation] tends to have the beginning of speeches and the end, and to realize that what happens in the middle of Shakespeare’s long speeches is that things get repeated. So that’s a good trick if you’re trying to work out what [Shakespeare’s] big speeches are saying. Look at the beginning, look at the end and that will probably tell you.

But [in Luhrmann’s adaptation] language is also cut to create meaning through different routes, through different ways of communication. One is visual. Shakespeare’s theatre, in the early part of his career, which is the date of Romeo and Juliet, is not actually very visual. It’s quite a verbal form. [Audiences] listen to descriptions and imagine them. It’s more like radio, almost. Luhrmann’s film is a very very visual film. It spends a lot of time [focusing] on setting and locations, [utilising various] camera shots [and editing techniques]. It communicates a lot visually. It’s good to be reminded that actually. What makes a really great film of Shakespeare is a real willingness to be quite radical with the text.

Emma Smith

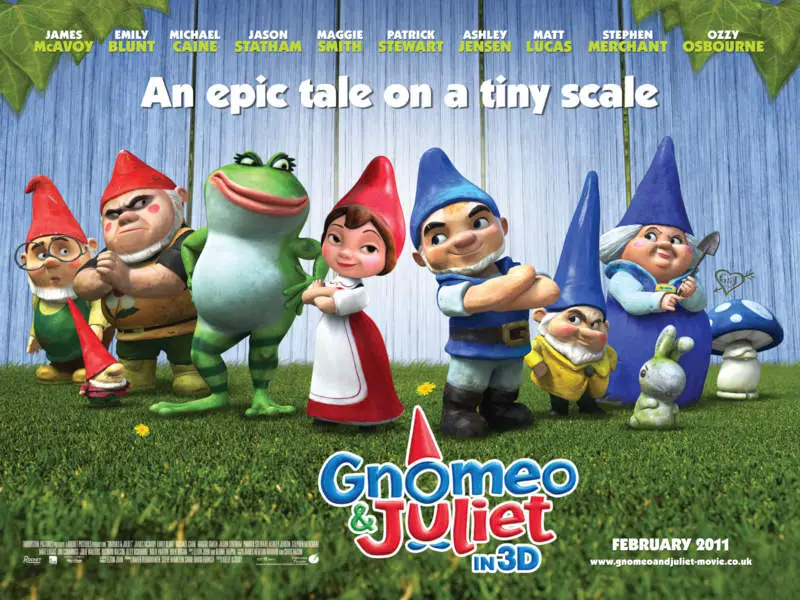

GNOMEO & JULIET (2011)

Shakespeare for kids! Full of puns. I love the queer-coded pink flamingo. The scene where he loses his lover is the most affecting scene in the whole film.

The Montagues and Capulets are red hatted versus blue hatted gnomes. Romeo is a revhead into lawnmowers. We’ve got the tragic love story bringing two warring tribes together, but because this is for kids, Romeo and Juliet don’t stay dead at the end.

OTHER STORIES WITH SHAKESPEAREAN INFLUENCE

Examples abound. Here are just a few.

YOUR HONOR (LIMITED TV SERIES)

Whenever a boy and a girl from two warring families start dating the plot will be compared to Romeo and Juliet.

Michael’s son and Jimmy’s daughter are currently seeing each other, which adds a Romeo-and-Juliet twist to the proceedings, albeit with the slight caveat that Romeo ran over Juliet’s brother with a car and Juliet doesn’t know about it.

Vulture recap of Your Honor, Season One, Episode Six

SUCCESSION (TV SERIES)

Succession borrows from Shakespeare in many different ways.

In common with Romeo and Juliet, we see an example of forbidden love between the children of two rival families when Kendall Roy starts seeing Naomi Pierce. The two families are embroiled in battle over who will succeed as the dominant modern media moguls. Kendall and Naomi bond over their shared drug addiction, and also because it’s not that easy to find someone else who knows what it’s like to be the offspring of a mega-wealthy media empire.

BASICALLY ANY STORY IN WHICH LOVERS KILL THEMSELVES OVER LOVE

Across the history of storytelling, across cultures, there are many.

RESOURCES

- The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare at Gutenberg Books (free, of course, since it’s long since out of copyright)

- In Our Time podcast with Melvyn Bragg: Romeo and Juliet

- Complete Works: Table Top Shakespeare: At Home: Romeo and Juliet performed by Terry O’Connor on YouTube

- OF PENTAMETER & BEAR BAITING – ROMEO & JULIET PART 1: CRASH COURSE LITERATURE #2

- LOVE OR LUST? ROMEO & JULIET PART 2: CRASH COURSE LITERATURE #3

- Romeo and Juliet resources at The British Library

English teacher Darren Gallagher keeps teaching resources online in a Dropbox which he shares for use, adaptation and sharing. For example:

- Romeo and Juliet Act 2 Scene 4: Is Tybalt really a ‘flat’ character’?

- Romeo and Juliet Act 2 Scene 5 Powerpoint

Header image: If Edward Hopper illustrated Juliet on her balcony, according to AI (Stable Diffusion).

HOW TO READ SHAKESPEARE

William Shakespeare, who lived in England from 1564 to 1616, is one of the world’s most popular and most captivating authors. Even four hundred years after his death, his plays still attract audiences around the globe. Why is that? In this course, you’ll learn who Shakespeare was, what kinds of plays he wrote, and what makes his body of work perhaps the greatest work of art ever created. In Episode Five, Professor Smith shares student-tested strategies for approaching Shakespeare’s plays as a first-time reader or audience member. You’ll learn how to engage with the structure, imagery, and poetic verse of Shakespeare’s language and with the particular way that Shakespeare constructs his characters and plots. You’ll also learn why performance is key to discovering the meanings of Shakespeare’s plays–and why there are always new meanings to be discovered.

New Books Network