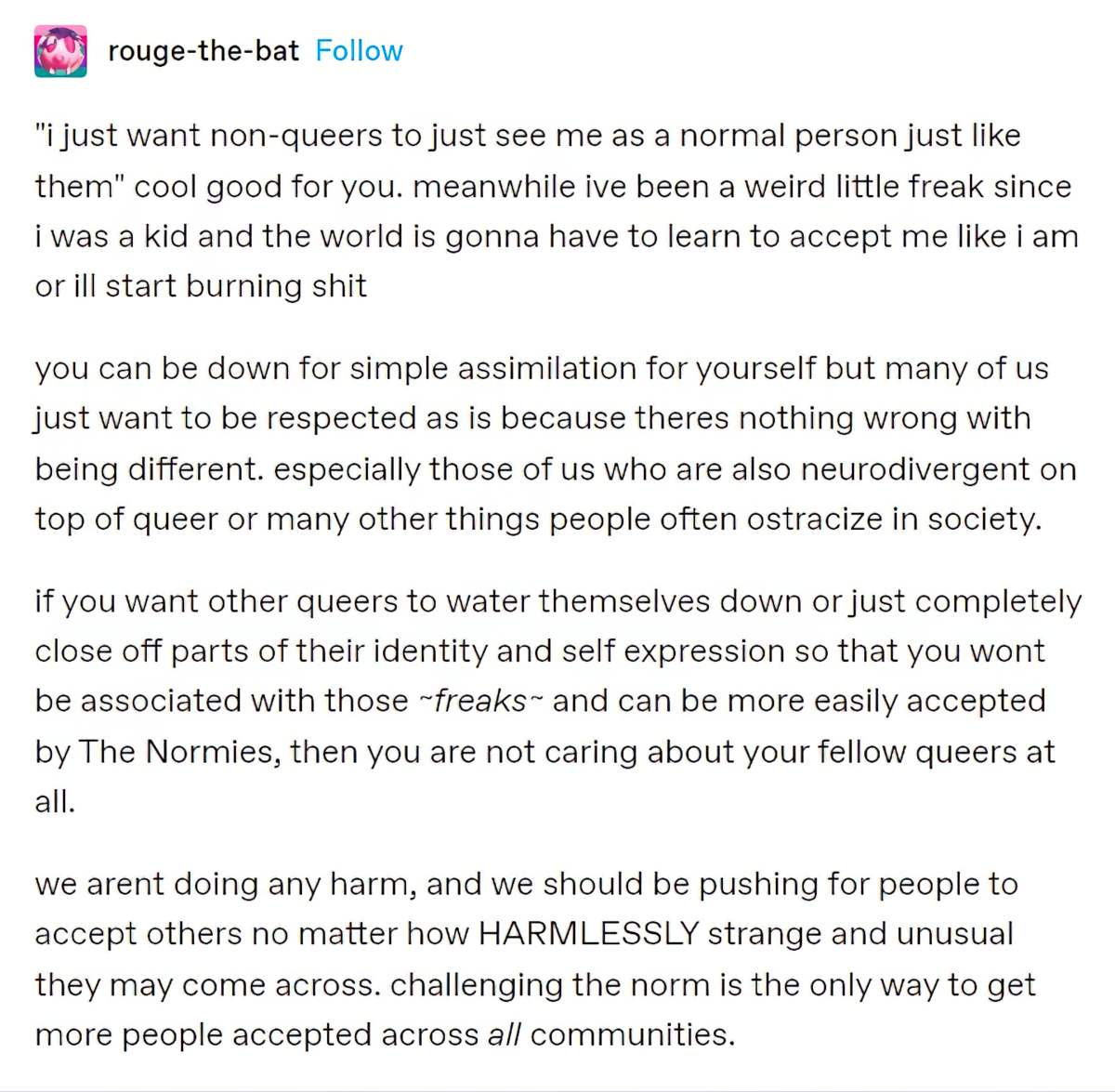

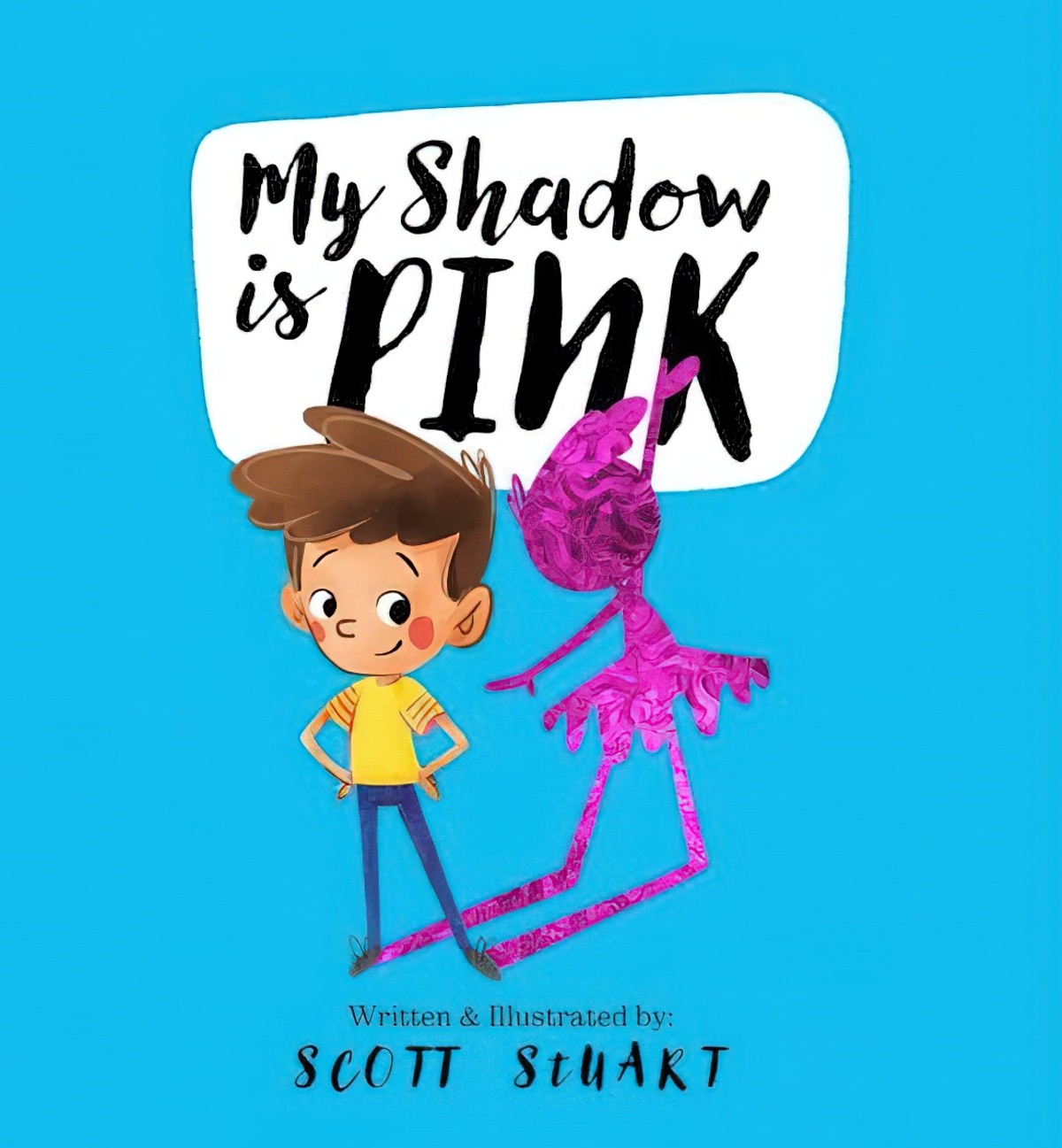

My Shadow Is Pink is a rhyming picture book by Australian author/illustrator Scott Stuart, perfect for Rainbow Storytime, or at any time in fact.

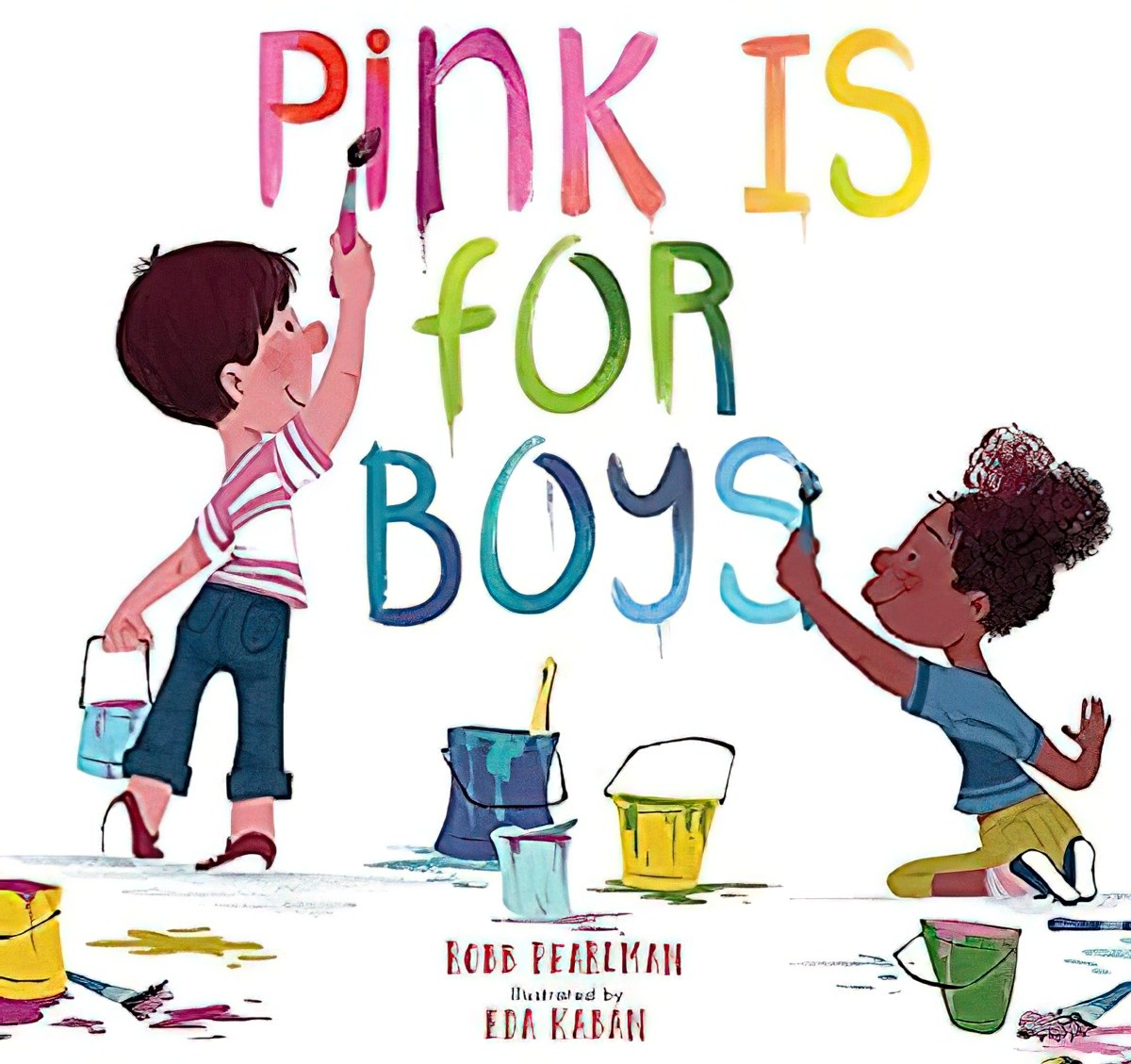

I’d encourage readers to compare and contrast this book with The Day The Crayons Quit by Drew Daywalt and Oliver Jeffers. The Crayons picture book is a mega bestseller, and I am therefore happy to hold it up as an example of gender messaging done badly, by creators (and publishers, and marketing teams) who clearly didn’t know what they were doing in the gender identity arena. Unfortunately, the creative team of The DayThe Crayons Quit do try to smash links between colour and gender… then end up reinforcing them. I’ll be generous and say it was by accident. I’ll be extra generous and point out that The Crayons (2016) is quite old now, in this rapidly changing aspect of culture.

In contrast, the creator of My Shadow Is Pink (2020) has secondary experience of gender expansiveness, observed in his own son. Stuart successfully achieves what others have tried and failed to do: to disentangle colour, clothing and play choices from gender. This is a vital first step in accepting variations on the gender binary.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SHADOWS

The plot of My Shadow Is Pink makes use of the shadow as a separate part of oneself. Humans have long been thinking about the shadow and its motivations:

FOLLOW a shadow, it still flies you;

The Shadow by Ben Johnson (from the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900)

Seem to fly it, it will pursue:

So court a mistress, she denies you;

Let her alone, she will court you.

Say, are not women truly, then,

Styled but the shadows of us men?

At morn and even, shades are longest;

At noon they are or short or none:

So men at weakest, they are strongest,

But grant us perfect, they’re not known.

Say, are not women truly, then,

Styled but the shadows of us men?

![SCHADUWEN VAN GISTEREN [1946] Wim de Mooy shadow](https://www.slaphappylarry.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SCHADUWEN-VAN-GISTEREN-1946-Wim-de-Mooy-shadow.jpg)

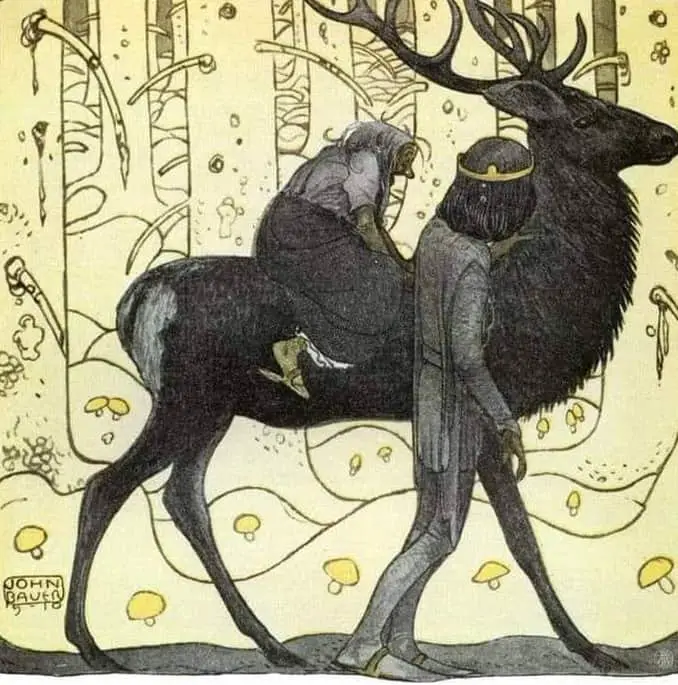

THE SHADOW IN THE HERO

In some cultures across history, the shadow-as-separate-being is an ancient and surprisingly fleshed-out idea. Though few of us these days give much thought to the shadow we cast, the idea of The Shadow In The Hero is well-known among writers. In The Hero of a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell wrote about various character archetypes in the mythic story. The ‘Shadow’ is the opponent, and represents the dark weakness in the hero, hence “Shadow In The Hero”. When heroes battle their opponents outwardly, they are actually battling their inner demons. Inner demons are the scariest demons of all.

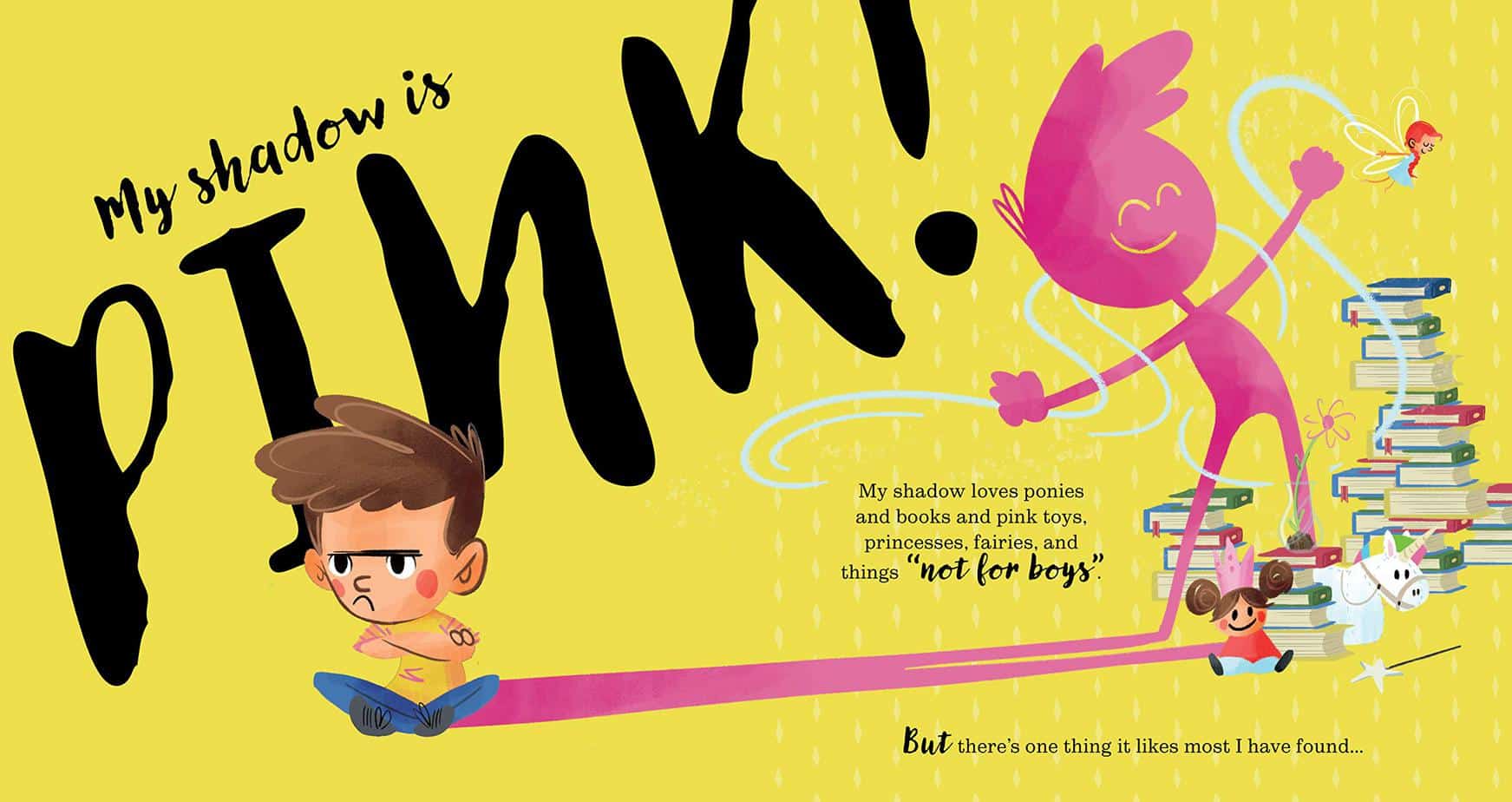

THE HORROR SHADOW

Shadows, like personal weaknesses, are inherently scary. Film noir makes the most of this, but shadows are utilised in every genre. Chris Van Allsburg utilises shadows to ominous effect in his picture books, notably in The Garden of Abdul Asazi.

Filmmakers frequently use shadows because the human imagination conjures up what is most terrifying to each person. This is an intelligent method because if they had to create a monster, they would be isolating the audience that isn’t scared by that monster. It is a simple, yet high effective way to evoke fear.

“Shadows in Horror Films: Fear of the Unknown,” Brogan O’Callaghan (2017)

Because the shadow has an inherent scariness, the idea of this scariness transfers into a picture book and allows the author to leave most of the scary incidents off the page. In My Shadow Is Pink, it’s important to leave the worst things off the page, for the same reason the creators of Schitt’s Creek avoided homophobia in their show. There are too few stories celebrating gender difference without the trauma. However, exposing the most secret and unusual part of yourself is always scary. To use the metaphor of a shadow is an excellent way of conveying the scariness while avoiding the trauma.

SHADOWS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Now to the concept of the coloured shadow. This is based on a very old, religious or supernatural idea: That your shadow is a part of you.

We see it in Ancient Egyptian culture. First, the Ancient Egyptians believed the soul comprised five separate parts:

- The Ren: the name given to a person at birth. Egyptians believed it would live for as long as that name was spoken or the person remembered.

- The Sheut: the person’s shadow or silhouette. Egyptians believed that the shadow contained part of the essence of the person.

- The Ib: a metaphysical heart. To ancient Egyptians it was the focus of emotion, thought, will and intention. They understood it as the seat for the soul.

- The Ba: personality. Everything that makes a person themselves.

- The Ka: the vital fire or spark which distinguishes living people from dead (makes sense: warm living bodies vs. cold dead bodies).

A person’s shadow or silhouette, šwt (sheut), is always present. Because of this, Egyptians surmised that a shadow contains something of the person it represents. Through this association, statues of people and deities were sometimes referred to as shadows.

The shadow was … representative to Egyptians of a figure of death, or servant of Anubis, and was depicted graphically as a small human figure painted completely black. In some cases the šwt represented the impact a person had on the earth. Sometimes people (usually pharaohs) had a shadow box in which part of their šwt was stored.

Wikipedia

I heard Jodi Picoult speak succinctly about the Ancient Egyptians and souls in a Radio New Zealand interview she did promoting her new novel, The Book Of Two Ways.

SHADOW WORK

In psychology and spirituality, “shadow work” is the practice of investigating parts of ourselves that we’d normally keep hidden. This often involves looking at what we perceive as our “negative,” “unattractive,” or “undesirable” impulses and traits. Shadow work is a concept popularised by Carl Jung.

Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. At all counts, it forms an unconscious snag, thwarting our most well-meant intentions.

Psychology and religion: West and East (ed. 1958), Carl Jung

STORY STRUCTURE OF MY SHADOW IS PINK

PARATEXT

My Shadow is Pink is a beautifully written rhyming story that touches on the subjects of gender identity, self acceptance, equality and diversity.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

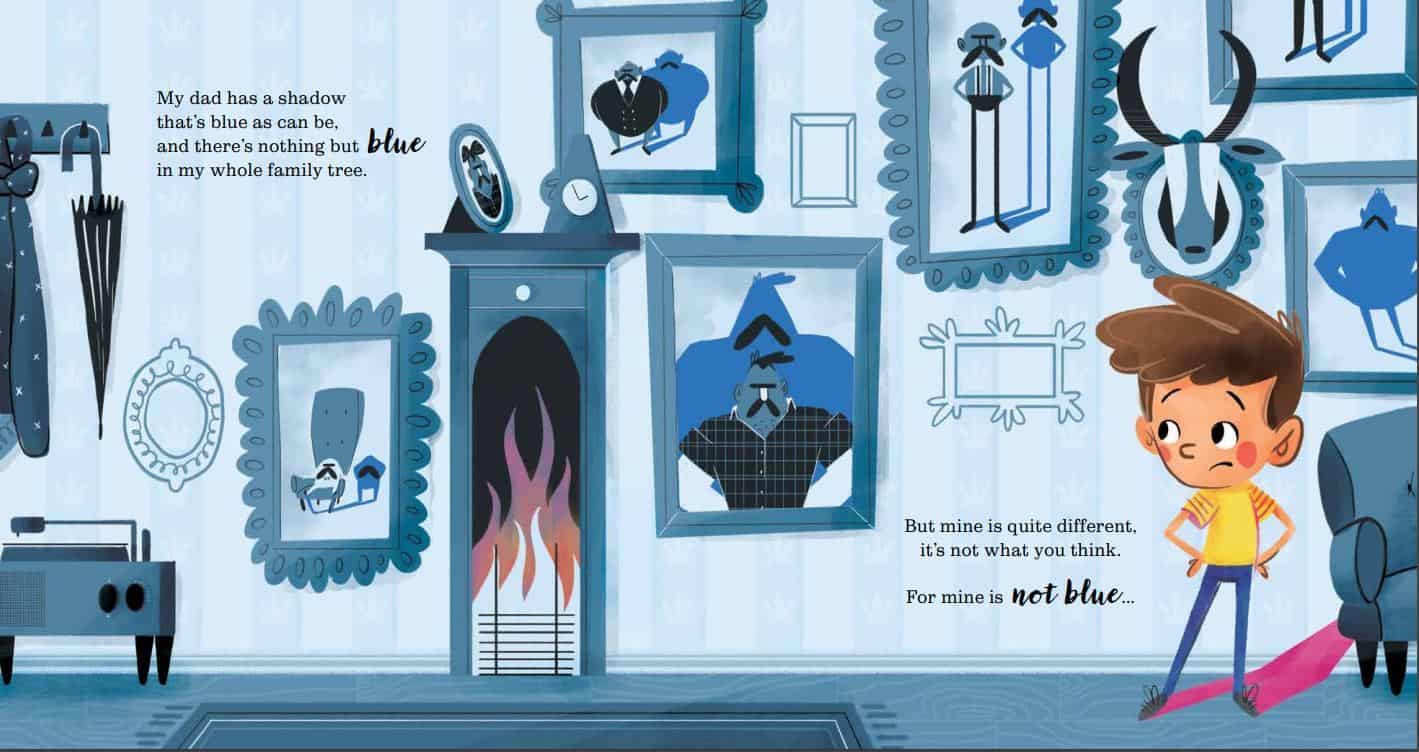

We all need to feel a part of something. When we feel different from our tribe, peer group or family, that can be a problem. “I cannot fit in when my shadow stands out.”

What I like about the set up of this story: The father is coded as ‘blue’, which contemporary readers will associate with ‘boys’. But then the entire family tree is described as blue. Since families don’t exist without women in them somewhere, this is a nice touch.

That said, I’d have liked to see some photos of women in the wall, to cement the idea that blue (the colour) is not a gender. (Later in the story, the father does bring out the photo album ‘of parents and brothers and sisters and aunts and uncles and others.) I wonder if there is a narrative reason why no women appear on the opening spread: Before his character arc, his misogyny means he dismisses and invisibilises women? By the way, there is no mother in this story, adding to the corpus of children’s stories with absent mothers. It’s interesting to think about why the mother may have been left out of this one.

DESIRE

At a plot level, the child wants to wear a dress to school despite being assigned male at birth.

At a psychological level, the child wants to both be themselves and also to “fit in”.

OPPONENT

There exist two distinct ways of fitting in. You can either pretend to be like everyone else, or everyone else can accept you for who you are. This particular story starts off with the father hoping to go down the first route. The father assures his child that this is “just a phase”.

Therefore, the child and the child’s father are in opposition. The father’s attitude is the dominant one in society. But it is impossible to repress that part of yourself which is elemental. In that story, this elemental part of the self is represented by the shadow.

PLAN

The child is too young to concoct plans and whatnot, but the five- or six-year-old version of a plan goes like this: I like to wear dresses, I will wear a dress to school.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

As is the case in many picture books, the battle comprises most of the story. We see the child looking sad and scared as they go out into the world (starting school) as a boy-coded kid in a dress.

To reiterate, I like that there’s no on-the-page insulting or bullying in this book. Sometimes parents are more fearful than they need to be, especially when it comes to Gen Z kids, who are the most accepting generation we’ve seen in memorable history. (Yes, you can thank their parents for that, and also probably ubiquity of the Internet.)

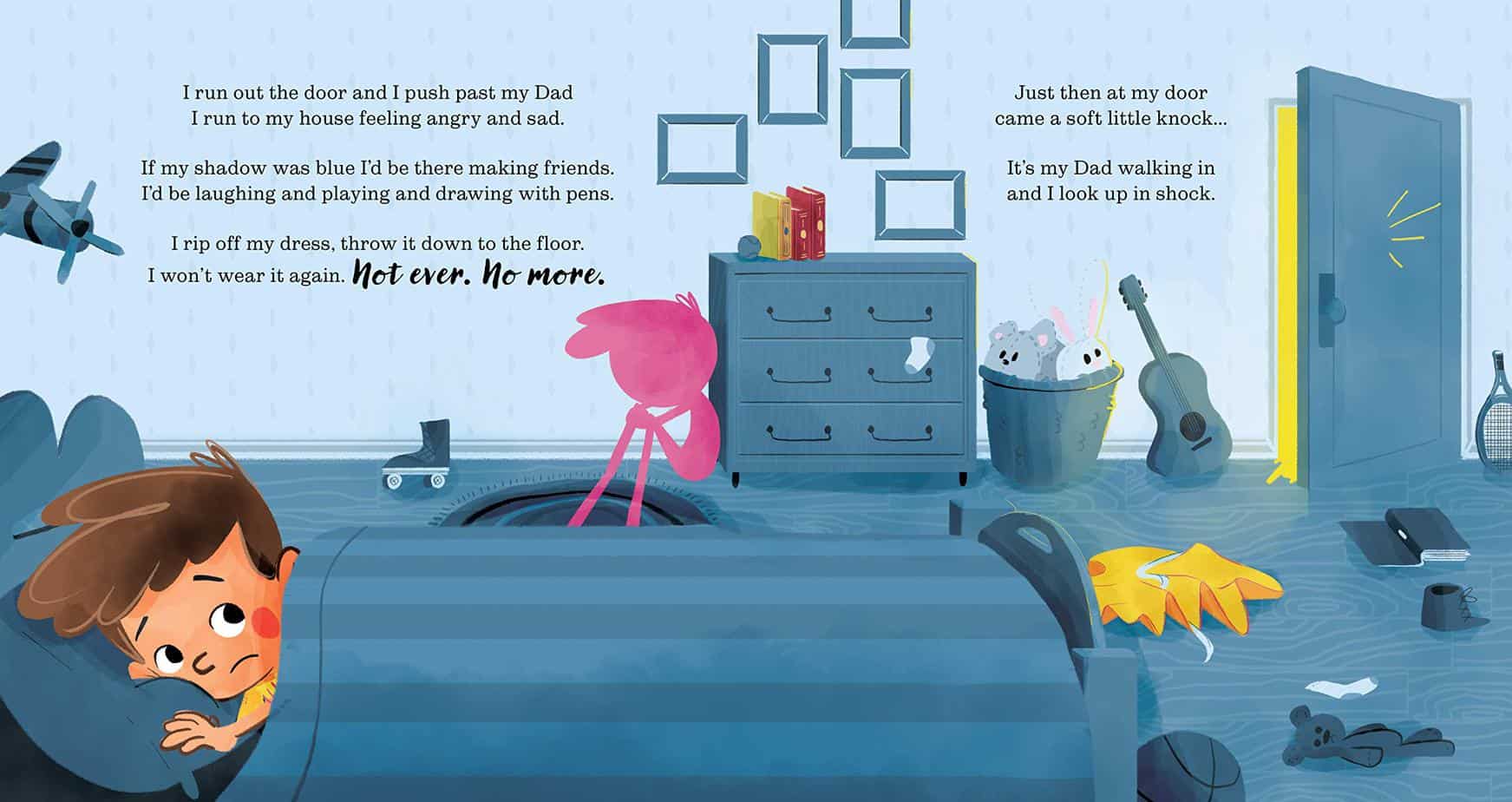

At the climax of My Shadow Is Pink, the child throws off the dress, determined never to wear it again. (We can assume bad things happened off the page.)

In the picture, the shadow is now separated from the child’s body; an abject rejection.

The word ‘abject’ is key here. This story is about abjection in Julia Kristeva’s sense of the word, explained in her 1980 work Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection.

ANAGNORISIS

The (hoped-for) revelation to the reader: If a big, manly man like this kid’s dad can wear a dress, then dresses, pageantry, kikis and all forms of camp expression are not the same thing as gender identity and sexual orientation. Ergo, pageantry should be for everyone.

Camp: A preference for reversal and rejection of sincerity….camp involves both a sense of doubleness — things are not merely what they seem to the naive viewer … camp involves a preference for reversal — the very bad now reinterpreted as good.

The double page spread which happens at this point in the story, with the spot illustrations of various people with various shadows is what makes this story shine. Until this point, the author/illustrator has had little choice but to run with the culturally dominant view that blue is connected to masculinity and pink is connected to femininity. At this point he subverts it, successfully with:

- A masculo- coded character with a cis-coloured shadow and a dual masculo-femme coded activity (businessman and painting)

- A femme- coded character with a cis-coloured shadow and a dual masculo-femme coded activity (fixing cars and cheerleading)

- A masculo- coded character with a masculo-coded shadow and a dual masculo-femme coded activity (weight-lifting and dancing)

The message on the verso is clear: Cis people don’t need to limit their passions in order to prove to the world that they’re cis.

On the recto side of the page we have another two examples, and in the mix:

- A cis girl who likes girls

Until this point, the story has been about gender expression, and possibly about gender identity. Now the story sneaks in some gay acceptance, which is very nicely done.

ON OFF-THE-PAGE CHARACTER ARCS

This is an example of a story in which the parent has the character arc, not the kid. The kid was always fine. The father started out scared of his kid’s identity, then morphs into the perfect, supportive parent.

I’ve started to notice something about stories structured in this way:

The first is that they do work. There’s something really heartwarming about seeing a burly father change. This conects to my theory about heartwarming stories about kindness: The less kind the character in the first place, the more heartwarming an audience will find their change of attitude. We absolutely crave stories about characters who ‘come good’. The bigger the character arc, the better we like it.

Here’s the strange thing: In such stories, the storyteller is under zero obligation to show why the unkind character changed their mind. We simply would not accept this if the father of this story were the focalising character. We’d go, hang on, why the sudden change of heart?

This is a feature of all forms of storytelling, not just of children’s picture books. Another example can be found in episode one of the TV series Lovecraft Country. A woman is required to stay at home for safety while her husband goes off on a trip to write a guide book for Black travellers. It is established at the beginning of the story that it is the wife who does a lot of the work of writing. She asks, “Why can’t I go with you?” Because safety, explains the husband, who ends up taking another woman along with him — a woman who nearly loses her life. But as episode one closes, we see the husband pick up the phone from a hotel room and tell his wife that she should join him next time. We haven’t been shown why he has had a change of heart.

So why does this work? Why do readers simply accept the father’s off-stage character arc without asking, “why”? I posit two reasons:

- The character arc happens off-stage. We therefore assume things have been ticking over with the dad — things we simply don’t know about. Maybe he’s been on the Internet reading up about LGBTQI+ issues. Maybe someone’s had a quiet word with him. Maybe he remembered a time in his own youth when he wore a dress and got teased and realises now that this was wrong… Any number of things could’ve happened, but the reader doesn’t need to know about them.

- We were always on the less empowered character’s side, right from the get-go. In My Shadow Is Pink we don’t need reasons for the dad’s character change explicated, because it was obvious from the start that the father was in the wrong, the kid was in the right, so it was a natural progression that the father would join us all on the right side, ie. the side of the viewpoint character. In Lovecraft Country, a modern audience with modern views on gender equality will be on the side of the wife who is required to stay at home despite doing the bulk of the writing work. This is why we accept character arcs when they happen from ‘wrong’ to ‘correct’ even when we don’t see the thing that spurred the shift in thinking. Whenever someone agrees with us in real life, we don’t need to know why, right? We only need to know their thought processes when they disagree.

NEW SITUATION

The advice this father gives to his child: “stand up with your shadow and yell THIS IS ME!” If the advice ended there, I’d criticise it for being insufficiently nuanced. But this is followed with “And some they will love you… and some they will not.. But those that do love you, they’ll love you a lot”.

This is the perfect way to end a book about gender identity in a world where trans rights are clearly still very much needing to be fought for.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Although this story is specifically about the acceptance of gender non-conformity, the message has a wider application: We must all accept ourselves, no matter who we are. It’s great to see a specifically gender non-conformity example added to what is already a massive corpus of ‘Be Yourself’ picture books of the non-controversial Elmer variety, about a fantasy elephant with patchwork skin.

RESONANCE

I hope that one day, a picture book such as My Shadow is Pink becomes wholly unnecessary, considered a strange artefact from a bigoted past. But for now, affirming stories such as My Shadow Is Pink are sorely needed, and I’m delighted that this one exists.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION