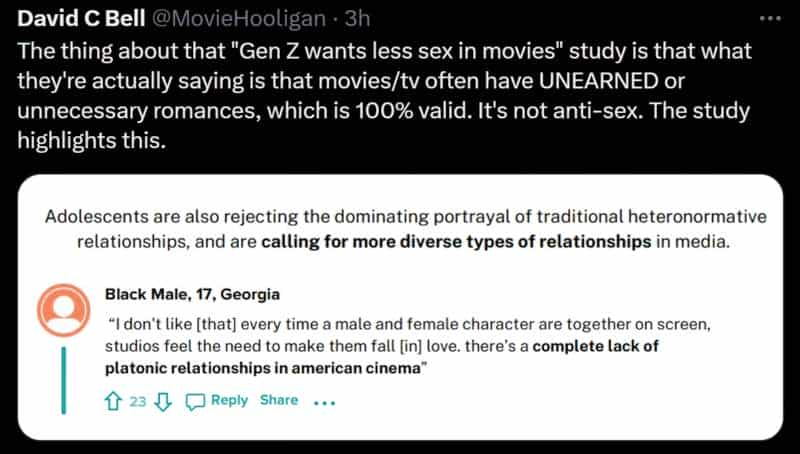

In October 2023 a study came out called Teens and Screams. It garnered much attention.

The prevalence of ‘sl*ts’ and ‘wh*res’ in young adult literature and schoolyard banter is enough to make a feminist mother weep. Our daughters learn early the same sexually oppressive messages that we learnt: that female sexuality is a prize to be given to (or taken by) a man.

Daily Life

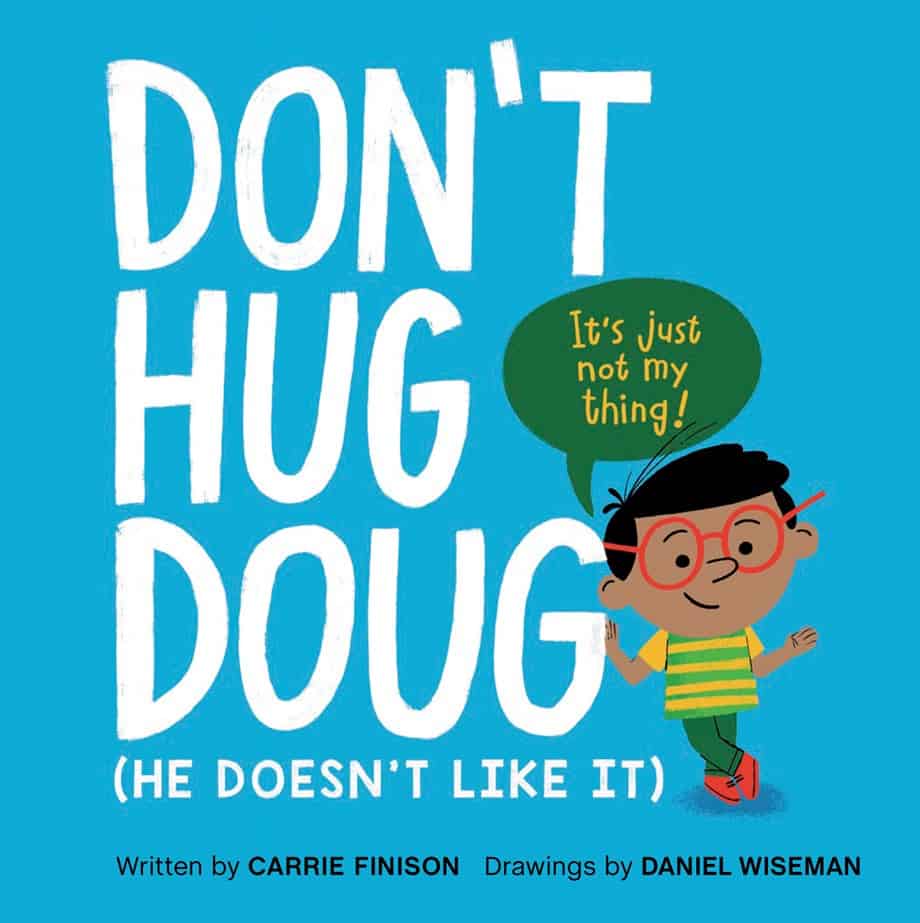

First of all, consent training starts young, way before the teen years.

Meet Doug, an ordinary kid who doesn’t like hugs, in this fun and exuberant story which aims to spark discussions about bodily autonomy and consent.

Doug doesn’t like hugs. He thinks hugs are too squeezy, too squashy, too squooshy, too smooshy. He doesn’t like hello hugs or goodbye hugs, game-winning home run hugs or dropped ice cream cone hugs, and he definitely doesn’t like birthday hugs. He’d much rather give a high five—or a low five, a side five, a double five, or a spinny five. Yup, some people love hugs; other people don’t. So how can you tell if someone likes hugs or not? There’s only one way to find out: Ask! Because everybody gets to decide for themselves whether they want a hug or not.

These are notes from the Kid You Not Podcast, Episode 10 combined with my own.

You won’t find men’s genitalia in quality literature.

A Librarian

Keeping our children innocent is certainly not protecting their innocence, because they are more vulnerable to believing any other kind of story they are told.

Jenny Walsh, Talking to your kids about sex, Daily Life

The sex in TV and movies can be simultaneously explicit and evasive. Sex, particularly non-committed sex, is typically presented as fun and advisable; rarely is it awkward or silly or challenging or messy or actively negotiated or preceded by discussion of contraception and disease protection. There’s always plenty of room in the backseats of those limousines, and nary a pothole in the road.

Peggy Orenstein, Girls and Sex

One way to discover what Americans are concerned about is to delve into the books they read. Or more tellingly, the ones they reject. […] “America seems to be very exercised about sex,” Mr. LaRue said.

Banned Books Week, NYT

You may have heard the phrase, “Children’s literature is both a mirror and a window,” meaning when children (indeed anyone) is exposed to someone else’s story, two things happen:

- We get a glimpse into someone else’s experience via the ‘window’

- We see ourselves reflected back via the ‘mirror’.

Since stories function as windows, they also function as ‘super-peers’ — teaching us not only how others live in the world, but also providing scripts on how to live a good (or a not so good) life.

Though writing about p*rn in particular, Peggy Orenstein’s description of the nuanced interaction between ‘media’ and ‘consumer’ is explained below:

Media has been called a “super peer,” dictating all manner of behavioural “scripts” to young people, including those for sexual encounters: expectations, desires, norms. In one era, they learn that you don’t kiss until the third date; in another, they learn that sex precedes an exclusive relationship. Bryant Paul, a professor of telecommunications at Indiana University Bloomington who studies “scripting theory,” explained, “I’ll ask students, “Think about how you learned what to do at your first college party. You’d never been to one, but you knew that couples would go off to someone’s room.” And they’ll say, “Yeah, from American Pie and all those movies..” So where are they learning their sexual socialization, especially in terms of more explicit behaviours? You’d be foolish not to think they’re getting ideas from porn. Young people are not tabulae rosae. They have a sense of right and wrong. But if they’re repeatedly exposed to certain themes, they are more likely to pick them up, to internalize them and have them become part of their sexual scripts. So when you see consistent depictions of women with multiple partners and women being used as sex objects for males, and there’s no counterweight argument going on there…” He trailed off, leaving the obvious conclusion unspoken.

Over 40 percent of children ages ten to seventeen have been exposed to porn online, many accidentally. By college, according to a survey of more than eight hundred students titled “Generation XXX,” 90 percent of men and a third of women had viewed porn during the preceding year. On one hand, the girls I met knew that porn was about as realistic as pro wrestling, but that didn’t stop them from consulting it as a guide. Honestly? It pains me to hear that the scatological fetish video Two Girls, One Cup was, for some, their first exposure to sex. Even if what they watch is utterly vanilla, they’re still learning that women’s sexuality exists for the benefit of men. So it worried me to hear an eleventh-grader confide, “I watch porn because I’m a virgin and I want to figure out how sex works”; or when another high-schooler explained that she watched it “to learn how to give head”; or when a freshman in college told me, “There are some advantages. Before watching porn I didn’t know girls could squirt.“

Peggy Orenstein, Girls And Sex

When Adam Herz submitted to studios the screenplay for what would become ‘American Pie’, he gave it the name ‘Untitled Teenage Sex Comedy That Can Be Made For Under $10 Million That Most Readers Will Probably Hate But I Think You Will Love’.

@qikipedia

Porn-viewing teenagers are not tabulae rosae and neither are book-consuming children.

- When children see only white people in books (with the odd token black kid) they learn that white is the norm.

- When children are heavy readers and find, without counting, that 2 out of 3 characters are gendered male, they learn that when women and girls take up 50 per cent of the space, they are taking up too much space.

- When children see that only men read newspapers in picture books they learn that newspapers — and keeping up with current affairs — is a male concern.

- When children see only heterosexual parents they learn there is no other upright way to live.

- When children don’t see doing their share of caring and housework — in books as in real life — they learn that women are naturally better suited to household duties.

To writers I would say: To what extent must this particular story be a window on this real, imperfect world, and to what extent can you provide a better, aspirational one while maintaining a recognisable milieu?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SEX IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

AN EARLY 20TH CENTURY EXAMPLE

Laura Ingalls Wilder, who wrote the semi-autobiographical Little House series with her daughter Mary from the 1930s, had a real life which wasn’t quite the fairytale depicted in the stories or in the Disney miniseries. Laura Ingalls married “Manly” Wilder at the age of 15. Manly was at the time 25. This age difference and the marriage of a bride so young was common and acceptable in that time and place, but by the 1930s had become a taboo subject in a feel-good story for children. The real age difference was therefore never mentioned.

Would this age difference be acceptable in a book for children today? We see in children’s literature what is considered acceptable at time of publication, with an extra tendency to sit on the conservative, didactic side of acceptable. In other words, children’s books tend to be slightly more conservative than the dominant culture, then move on. A bit like churches.

(For more on Laura Ingalls Wilder, listen to Stuff You Missed In History Class Episode December 23, 2013.)

Anyhow, that choice — to leave the age gap completely off the page — is a telling writerly decision.

THE 1970S: JUDY BLUME

In many young adult novels, teenage sexuality is defined in terms of deviancy — even when the message to the reader is a Judy Blume special: “Your masturbating/wet dreams/desire to have sex/(fill in the blank) is normal.” Such novels reflect cultural norms that tend to define teenage sexuality in terms of deviancy in an attempt to control adolescents; nonetheless, reassurances to teenagers that their actions are normal still start from the assumption that someone thinks their actions are not.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

Seelinger Trites is very good at explaining that thing where authors try to say one thing and accidentally (inevitably) end up saying something else as well. This reminds me of a real-life incident recounted to me by a friend: An older woman approaches a younger woman and says, with earnest sincerity, “You’re lucky you’re so pretty.” Maybe this older woman saw that as a compliment, but the fact she saw the need to say it suggested there may be people in this world who don’t think it, or that the younger woman needed to hear it, because she may have been getting a different message. In any case, the younger woman didn’t feel comfortable about ‘the compliment’, because here’s a sad fact of life: It’s impossible to offer reassurance without also making (implicit) reference to the troubling side.

That aside, Judy Blume’s Forever (1975) revolutionised the way sex was portrayed in teenage literature. Forever wasn’t actually a groundbreaker — there were books which came before and they did the same thing. Before Forever we had novels by Norma Klein and others. They equalled Forever in content though weren’t quite so well written. So Forever is the groundbreaking book best remembered today.

(When you look closely at a Judy Blume novel you’ll be struck by how perfectly they are plotted. In this post I take a close look at Are You There, God? It’s Me Margaret. You can’t fault it.)

The striking thing about Forever is how clinical and de-eroticised the sex actually is. There really is nothing titillating about it, despite how often it was banned at the time of publication.

Forever looks super conservative by today’s standards.

- First you seek advice by going to the clinic like a good girl and get yourself some birth control

- The book describes vaginal examinations and how to have them (in the United States)

- It also describes penises

- Premature ejacul*tion

- Impotence

- Intercourse during menstruation

- STD (called VD back then)

- ‘Broken hymen’ (in fact hymens don’t break — they stretch)

- Premarital pregnancy

- Giving babies up for adoption

- Play-by-play on how to have sex (or one kind of sex)

- The young woman is assumed to take sole responsibility to take birth control.

The text tries to liberate teenage sexuality by communicating that curiosity about sex is natural, but it then undercuts this message with a series of messages framed by institutional discourses that imply teenagers should not have sex or else should feel guilty if they do.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

Although this ideology is very much of its time, this book provides a sensitive treatment of sex, and helped quite a lot of young women worried about the hygiene and practicalities of the sex itself. Even though sex is much more a part of young adult literature these days, it’s still hard to find stories which address young girls’ concerns in such a practical manner rather than the emotional side.

Also, the idea that health of the family is the girl/woman’s responsibility has hardly gone away. You can find daily examples of advertisements, for health food, for dentists, for glasses, which are aimed at women. Just this morning I had a newsletter in my inbox advertising a (dodgy) app which helps to ‘educate mothers’ about health for the sake of our families:

THE 1990S AND THE AIDS EPIDEMIC

It’s only now that I’m middle aged that I realise the extent to which the AIDS epidemic influenced the messages my generation received about sex, coming-of-age in the 1990s. We received no real sex education; we received scare mongering. We put condoms on bananas and took notes about all the different kinds of STDs. We were made to line up boy-girl-boy-girl in a shockingly heteronormative exercise, then told that this was a visual representation for how disease and infection can spread through a community like wildfire. The clitorls was not mentioned once.

I honestly think if I had read one book with a bisexual protagonist where it was presented as not something shameful, then that would have saved me many years of grief and anxiety.

Antonia Angress at Electric Lit

There wasn’t much to be gleaned from young adult literature of that time, either. That, too, was influenced by the AIDS epidemic, and authors became leery of writing sex scenes in their books for teenagers. The 1990s was when the Sex Novel evolved into the AIDS novel. An early example was published in 1986. It was called Night Kites, by M.E. Kerr.

A classic young adult novel from this era is Weetzie Bat, published 1989.

Weetzie Bat… is predicated on the notion that sexual expressions of love are good, whether they are expressed between people of the same or opposite sexes. But Block cannot escape the trappings of our culture: writing within a post-AIDs culture, she only sanctions sex that occurs between committed, loving couples in permanent relationships.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

(I wouldn’t call 1989 a post-AIDs era… 1989 was right in the throes of it from what I remember. But I get the point.)

POST-WESTERN AIDS

Fast forward to 2004. AIDS is under control in the West, or at least feels like it. It’s only now that we get Melvin Burgess’s Doing It, with a gritty exploration of sexuality. This book would have been unthinkable in the 1990s. My own sex education in this decade consisted of sexually transmitted diseases and the labelling of the reproductive organs. We also learned how to put a condom on, using our fingers as stand-in members, but even that is related to avoiding diseases. There was nothing whatsoever about relationships, consent, or the idea that sex can be pleasurable. Perhaps adults just assumed we would know this already, and it was their job to provide ‘protection’? But it wasn’t at all obvious.

RETRIBUTION AND SEX IN MODERN YOUNG ADULT NOVELS

Sex is no longer a taboo subject and is therefore more common. But it is never, even today, something that just happens; it’s almost always a key aspect of the plot and there are always consequences. If the sex is reckless then invariably the female protagonist has a pregnancy scare or ends up pregnant. Despite the fact that now it is more common to depict protagonists having sex, it has not become normalised.

An example of this kind of morality occurs in a subplot of Numbers by Rachel Ward. The male character dies, then lo and behold, the female character is pregnant. [I’ve noticed a lot of war stories contain this plot. The male has to go off to war, and it’s discovered that the woman left at home is going to have his, or someone else’s baby.] Sex cannot pass by unnoticed.

In Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman, the two main characters who are deeply in love have sex. The boy dies; the girl gets pregnant.

In Twilight Bella and Edward get married, have sex, and Bella dies (sort of). Again, huge consequences. In Twilight, the absence of sex is the sex. [The Erotics Of Abstinence.]

With the notable exception of the Twilight Series, the culture has moved on from the idea that sex must only happen within marriage, but hasn’t moved all that much further; sex is still something you do only within a loving, secure relationship. You must think carefully and deeply about birth control first.

In the literature of antiquity, sex is almost a last resort for the expression of love, and it seldom ends well. It’s the classic pitfall of the Old Testament.

Paris Review

YOUNG ADULT NOVELS AND SEXUAL IDEOLOGIES

Some of these ideas seem so ‘obvious’ that they do actually need to be pointed out as ideology.

Seelinger Trites points out that even when there is no obvious ideology in a young adult novel which deals with sex, there is usually the following power dynamic:

the character’s sexuality provides him or her with a locus of power. That power needs to be controlled before the narrative can achieve resolution.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

POWER = GOOD SEX AND SATISFYING ORG*SM

Well, who would argue with that?

Sexual potency is a common metaphor for empowerment in adolescent literature, so the genre is replete with sex.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

It’s worth pointing out because then you’ll start noticing how rare it is for teenage characters in young adult novels to achieve satisfying sexual experiences.

Seelinger Trites points out that teenage characters in young adult novels agonise about almost every aspect of human sexuality:

- decisions about whether to have sex

- issues of sexual orientation

- issues of birth control and responsibility

- unwanted pregnancies

- masturbation

- org*sms

- nocturnal emissions

- sexually transmitted diseases

- pornography

- sex work

The occasional teenage protagonist even quits agonizing about sexuality long enough to enjoy sex, but such characters seem more the exception than the rule.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

HAVING SEX MAKES YOU A GROWN UP

Sex is a rite of passage. This is a weird one, because it often occurs alongside the message that…

SEX IS POWERFUL SO BE CAREFUL WITH IT

STRUCTURE OF A YOUNG ADULT ROMANCE NOVEL

There’s more than one way to skin a cat, but here’s a very typical sequence in a young adult romance. Summarising from Roberta Seelinger Trites:

- Two teenagers feel sexually attracted to one another

- Something will keep them apart. During this period, each character thinks the attraction is unrequited.

- They’ll eventually share their feelings with each other and learn that it’s mutual.

- However, they don’t immediately get into it. They will agonise about what happens next, scared and worried about sex.

- They do end up expressing their passion with some sort of sexual contact.

- Maybe one character or the other regrets the action, because there are unwanted consequences. This might be pregnancy, family/peer group repercussions, or one character might betray the other.

- The two characters may end up together at the end of the novel, or they may break up.

The message in this case: Sex is powerful and can hurt people, so be careful when you mess around with it. Make sure you’re ready.

THIS IS HOW TO DO SEX, YOUNG FOLK

Many young adult novels seem to assume that the reader has a sexual naivete in need of correction. Some young adult novels seem more preoccupied with influencing how adolescent readers will behave when they are ot reading than with describing human sexuality honestly. Such novels tend to be heavy-handed in their moralism and demonstrate relatively clearly the effect of adult authors asserting authority over adolescent readers.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

BE CAREFUL, GIRL GATEKEEPERS

This idea isn’t dead, so writers still need to be careful to avoid the message expressed in your typical 1970s young adult novel:

Sexual liberation is a good thing, but … it is the girl’s job to make sure that male sexuality is not so liberated that she becomes victimized.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

Classic examples of these books include:

- Forever (1975) by Judy Blume

- My Darling, My Hamburger (1969) by Paul Zindel — a teenage girl is hurt by her own lack of control. Zindel condemns the character he creates who has an abortion.

- Edith Jackson (1978) by Rosa Guy — another teenage girl is hurt by her own lack of control. Guy seems pro-choice and applauds her character she creates who has an abortion but, like Zindel, her book implies that promiscuous sex in the first place is the real problem.

- Weetzie Bat (1989) by Francesca Lia Block — Weetzie gets beaten up and date-raped when she does not carefully guard her sexuality early in the novel.

- It Happened to Nancy (2004) by the editor of Go Ask Alice — an egregious example of victim-blaming. A 14-year-old date-rape victim contracts AIDS and dies.

DRUG USE LEADS GIRLS INTO SEX WORK

Go Ask Alice (1971) is a good example of the idea that drug use leads directly to (terrible) sex. The narrator of the journal ends up prostituting herself to buy drugs. Go Ask Alice was well-known in the 1990s for being anti-drug, but it’s easier to gloss over the ideology around sex.

Many people assume that drug use is what leads women to enter the sex work industry in the first place. But those people have it ass-about. Women commonly enter the sex industry clean and of their own volition (bearing in mind that choices aren’t made in a vacuum). It is true that sex work and drug use are linked. But the sex industry itself lends itself to drug use and abuse. (Incidentally, the same can be said of homelessness. Homelessness leads to drug addiction, not the other way around.)

The real relationship and the link between drug addiction and sex work is much more complex than the simplistic causal attribution of sex work to drugs. Drugs and sex work are interconnected in a vicious cycle of violence and corruption and in most instances they affect the most vulnerable parts of society. This link between them does not imply that drugs are responsible for pushing women into sex work. Sex work and drug use can have a merely coincidental connection and both can be the symptoms of traumatic experiences in the lives of the women involved.

Unveiled: The sex industry and drug abuse

WHEN EXPLICIT IDEOLOGY GOES SIDEWAYS: FROM TITILLATION TO VOYEURISM

I faced this issue when watching Mad Men, which hooked me in but annoyed me at the same time. I have friends who can’t watch it because, for them, watching sexism in action is not entertainment. Did Mad Men depict sexism in order to critique it, or did it promote it? For a few seasons there, titillation definitely won out. There’s nothing wrong with titillation in itself, though it often occurs alongside objectification and violence, sans the encouragement to critique. In the end, it’s impossible to make a distinction when it comes to Mad Men. The same can be said for many stories aimed at a young adult audience.

Forbidden by Tabitha Suzuma is about incestuous sex between a brother and sister. In this case the brother ends up dead. Contemporary teen culture has no trouble with eroticism/titillation. Forbidden provides more than simply titillation, instead putting the reader in the situation of a voyeur.

Fade by Robert Cormier is another young adult book largely about an incestuous brother/sister relationship. The main character is able to turn invisible, which allows him the role of voyeur as he sneaks into houses. The reader, of course, accompanies him on this ride. Robert Cormier’s Fade presents all forms of deviation: incest, rape, prostitution, voyeurism, in an incredibly harsh and provocative way which truly questions the intrusion of sex in the lives of teenagers. This book provides no solace nor emotional understanding, but I was both highly entertained and disturbed by it as a 14 year old. I read it later and was slightly bored by it. This wasn’t because I knew the plot — enough time had elapsed for me to completely forget about that. I only remembered I had enjoyed it. (Perhaps you have had a similar experience revisiting children’s literature — a good reminder that stories affect teenagers differently.)

WHERE ARE THE BOOKS ABOUT THE TEENAGE MALE SEXUAL EXPERIENCE?

Most experiences of sex in young adult novels are female experiences. There’s the notable exception such as Melvin Burgess’s Doing It, mentioned above, but that was precisely so notorious because no other book before had presented sex from the perspective of a teenage boy. As erotic and explicit and pornographic as this book is, it’s still explicitly didactic: “This is not the way you treat girls.”

A large proportion of young adult readers are girls. Young adult romance skews even more female. Depending on your ideology, whether we like or not, to some extent the sex in young adult literature is gendered. A lot of the most commercial fiction seems to have the aim of tucking its girl readers into particular feminine roles — sexual and gender roles. For example, in young adult fiction that appeals to girls, sex is emotional. [Girls are often passive, too, waiting for boys to ask them out, not learning about themselves.]

The reasons for this are probably so obvious it’s hardly worth pointing out: There is an alternative for learning about sex as a teenager: The Internet. Pretty sure boys are seeking out their sex education somehow, though it’s not from young adult romance. Girls are doing that too, but perhaps it is not the ‘good girl’s option’ to look to those other types of media. Young adult romance is an acceptable way to learn about sex even in conservative homes. There is something more wholesome-feeling about reading a novel compared to watching a film clip, say. Also, the vast majority of Internet porn is made with a male audience in mind, and over 80 per cent of it depicts violence against women. (Yes, that statistic does include BDSM, which can be consensual — still scary for young people.) Internet porn is not a safe and welcoming place for girls to learn about sex. In fact, it is actively terrifying. (It’s not a good place for anyone to learn how sex is done. That’s not what porn is for.)

INTO THE RIVER BY TED DAWE

Into The River is a New Zealand young adult novel which caused a furore when it won a big literary prize. It would probably have otherwise gone under the radar, but first it was banned for under 14s then, after much discussion, the ban was lifted.

Although the book describes a number of “unacceptable, offensive and objectionable” behaviours, the board said the book “does not in any way promote them”.

This story is social realism done very well. Speculative fiction works so well in young adult stories because adolescence is an overwrought time. Everything is at full throttle. When that tendency is explored in social realism sometimes it becomes melodramatic. But in a magical world, that same drama seems almost persuasive.

Though explicit, the sex scenes are in context. The moral panic that came about is often directed at prize winners.

Compare the content of Into The River with Singing My Sister Down, the short story by Margo Lanagan. Why are more gatekeepers not outraged over that? Lanagan’s short story shocks equally, but it contains no sex. So it seems to be sex that shocks people. Also violence and drugs, but mainly the sex.

There is a real sweetness about the main character of Into The River. There’s no explicit and direct message, but Dawe holds a mirror up to society and asks the reader to take a hard look.

THE CULT OF VIRGINITY

The Gossip Girl series has been described as Sex In The City for modern teenagers. Although there is sex, it is littered with consequences and always for the girl. The character Blair spends the entire first novel gearing up to have sex with her boyfriend, who she has been seeing for two years.

(For more on the Gossip Girl series, series such as this have been criticised by Naomi Wolf. This paper further delves into the role of these books and the impact they may/may not have on teenage girls.)

A book of short stories called Losing It, written by many prominent different children’s authors, write about lots of different ways of losing virginity. So many books revolve the plot around two people having sex and one of them is a virgin. Losing virginity is like a gate through the door into adulthood. Virginity is a strong symbolic obstacle.

PREGNANCY AS REPURCUSSION

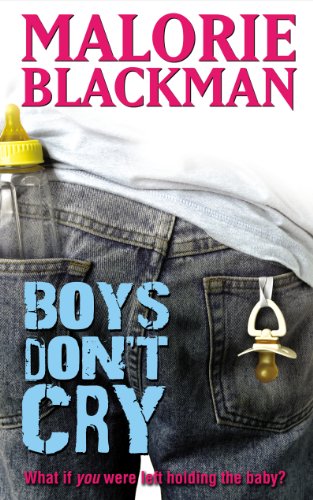

Malorie Blackman’s Boys Don’t Cry is a rare example of a story about teen pregnancy that is not all about the girl. He doesn’t know his former girlfriend has had a baby when she turns up one day and leaves him with their baby.

The books featured above are the Big Books about sex and teens, and there are almost certainly lesser known books which take a more mature [less didactic, more naturalistic] view of teenage sex.

Before Margo Lanagan switched to writing fantasy, she was writing social realism. In one of her early novels, The Best Thing, a teenage girl is pregnant, but Lanagan subverts our expectation of motherhood as punishment; she instead simply becomes a mother. And everything is okay for her, no better or worse than new mothers of any age. Diablo Cody also did this when writing the screenplay of Juno.

LGBTQIA+ SEX

Sex in young adult fiction is largely heteronormative and has only recently started to branch out into stories about other sexualities and gender identities.

That said, one of the earliest (the earliest?) was published in 1969: I’ll Get There, It Better Be Worth The Trip by John Donovan. Unfortunately, LGBTQIA+ novels of the 1970s always seemed to end with the gay character killed in a car accident. They became known as ‘Death by Gayness’ books. The lead character presumably died as punishment for being gay — not the sort of message anyone would have taken heart in.

The first young adult novel to deal with lesbian identity was Ruby by Rosa Guy in 1976. But Annie On My Mind by Nancy Garden (1982) remains more iconic.

Vanessa Wayne Lee is a scholar who divided lesbian novels into three main categories:

- Stories that assume lesbianism needs to be normalised. These stories often come across like information books with a bit of a story wrapped around them. (Like Judy Blume’s Forever is basically a sex manual.) She calls these “education texts”

- Stories that explore the formation of lesbian identity (coming out stories)

- Stories decenter the sexual identity of the character. Gayness will still be problematized but identity isn’t the central issue. Wayne Lee calls these “post-modern”. When Wayne Lee made these distinctions, she noted that this last category tends to be found in novels for older readers, but that has since changed in young adult.

THE HOMOPLOT (BETTER KNOWN THESE DAYS AS COMING-OUT STORY)

The traditional approach to [LGBTQ] stories is summarized in Esther Saxey’s Homoplot: The Coming-Out Story and Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Identity (2008).

- The protagonist is “most likely . . . a troubled teenager”

- the plot, resolution, and homoplot narrative itself create, change and shape new identities

- discourses of sexual identity help to create what they purport to describe.

- Thus the coming out story, which purports to describe a pre-existing sexual identity, is simultaneously contributing to the cultural construction of this identity.

Am I Blue: Coming Out From The Silence (1994) was the first young adult anthology dealing with gay and lesbian issues.

These days many young adult novels include/star a LGBTQ character and the queerness is not The Problem. They more and more just happen to be gay. An example of this is David Levithan’s Boy Meets Boy (2003). In this story the homecoming queen is also the star quarterback. TV series Schitts Creek was also a wonderful example of this. Jacqueline Woodson, Nancy Garden, and Stacey Donovan depict lesbianism in far more complex ways than could be imagined in the 1970s and 1980s.

CLICHES AND PITFALLS

- Positioning non-cishet identities as a threat or problem

- The LGBTQIA+ character not only suffers persecution, bullying, or other harassment because of their sexual orientation, but also fails to question the injustice of that treatment

- The death as punishment story, in which a gay character dies because they are gay — avoid. (This is reminiscent of the pregnancy as punishment for sex story about heterosexual teenage girls.) In general, endings which serve as more cautionary than hopeful.

- Less obviously problematic but still a problem: A story in which homosexuality is presented as just like heterosexuality. The aim here is to normalise, but this way of normalising homosexuality is highly problematic, not least because it uses heterosexuality as the basic standard and model. Anything outside that norm inevitably becomes a kind of deviation, undermining the whole intention.

- There are some stereotypes which play into some highly problematic beliefs about homosexuality, for instance the domineering mother. It has been thought that gay men become gay because of an overbearing mother (and passive male role model), so bear that in mind when creating the character a gay teenager’s mother.

- Related to that, homosexuality in a problem novel can sometimes seem like the author is saying that this problematic life event lead to the homosexuality. That’s the gayness as deviation and disorder mentality.

- Gay sex as pleasurable is too rarely depicted in young adult. Stories tend to be all about the politics around it and not about the sex itself.

- Stories about lesbians often stereotype lesbians as either butch or femme, as if those types are the only ways lesbians express themselves

- Conflating issues of sexual orientation and gender identity

- Even when traditional texts affirm LGBTQIA+ populations, authors may simply be concerned with making diverse orientations and identities visible, introducing it to heterosexual audiences as spectacle rather than addressing the audience most invested in self-discovery.

- LGBTQIA+ tend to be presented as types rather than individuals, and as support to the protagonist rather than of primary importance to plot or reader.

- In lesbian love stories, it’s not enough to simply take a cishet romance and switch out the boy for a girl. Progressive novels move toward celebrating the real differences in the experiences and subject-formation of LGBTQIA+ teen characters.

- On-the-page asexuality has historically been non-existent.

ON PITFALLS AND WRITING THE QUEER SPECTRUM

- See the paper Creating Realms of Possibilities from Dail and Leonard

- Also Would You Want To Read That? Using book passes to open up secondary classrooms to LGBTQ Young Adult literature from Emily S. Meixner

- And Creating A Space for YAL With LGBT Content In Our Personal Reading from Katherine Mason

- Connecting LGBT To Others Through Problem Novels from Hayn and Hazlett

- The Heart Has Its Reasons by Cart and Jenkins was published in 2006 and is a groundbreaking study of LGBTQ literature. The Heart Has Its Reasons creates an indispensable typology for finding and evaluating LGBTQ literature for young adults.

- “I wanted something 100% pornographic and 100% high art: the joy of writing about sex by Garth Greenwell in The Guardian

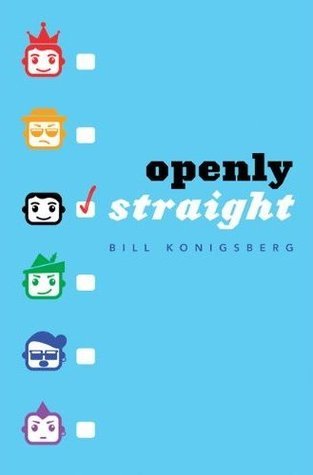

Rafe is a normal teenager from Boulder, Colorado. He plays soccer. He’s won skiing prizes. He likes to write.

And, oh yeah, he’s gay. He’s been out since 8th grade, and he isn’t teased, and he goes to other high schools and talks about tolerance and stuff. And while that’s important, all Rafe really wants is to just be a regular guy. Not that GAY guy. To have it be a part of who he is, but not the headline, every single time.

So when he transfers to an all-boys’ boarding school in New England, he decides to keep his sexuality a secret — not so much going back in the closet as starting over with a clean slate. But then he sees a classmate break down. He meets a teacher who challenges him to write his story. And most of all, he falls in love with Ben . . . who doesn’t even know that love is possible.

This witty, smart, coming-out-again story will appeal to gay and straight kids alike as they watch Rafe navigate feeling different, fitting in, and what it means to be himself.

Queer Anxieties of Young Adult Literature and Culture

Young adult literature featuring LGBTQ+ characters is booming. In the 1980s and 1990s, only a handful of such titles were published every year. Recently, these numbers have soared to over one hundred annual releases. Queer characters are also appearing more frequently in film, on television, and in video games. This explosion of queer representation, however, has prompted new forms of longstanding cultural anxieties about adolescent sexuality. What makes for a good “coming out” story? Will increased queer representation in young people’s media teach adolescents the right lessons and help queer teens live better, happier lives? What if these stories harm young people instead of helping them?

In Queer Anxieties of Young Adult Literature and Culture (UP of Mississippi, 2020), Derritt Mason considers these questions through a range of popular media, including an assortment of young adult books; Caper in the Castro, the first-ever queer video game; online fan communities; and popular television series Glee and Big Mouth. Mason argues themes that generate the most anxiety about adolescent culture—queer visibility, risk taking, HIV/AIDS, dystopia and horror, and the promise that “It Gets Better” and the threat that it might not—challenge us to rethink how we read and engage with young people’s media. Instead of imagining queer young adult literature as a subgenre defined by its visibly queer characters, Mason proposes that we see “queer YA” as a body of transmedia texts with blurry boundaries, one that coheres around affect—specifically, anxiety—instead of content.

New Books Network

TEENAGE EROTICA

House Of Holes has been recommended in major publications as a good example of erotica for a teenage audience. Erotica, of course, is a different thing from ‘the odd sex scene that crops up in typical young adult literature’.

The good news is that there is nothing in House of Holes that we wouldn’t want our youth to read. Indeed it is exactly the sort of filth that you would want them to read first (if you don’t mind exposing them to something so decidedly heterosexual).

In the traditional sex talk, parents don’t say much about pleasure—presumably neither party wants to get into details. But wouldn’t it be nice for parents to have a way to convey our highest ideals on the subject? House of Holes will introduce impressionable readers to many interesting sexual possibilities without a whisper of stereotype or slur.

The New York Review Of Books

TRENDS IN THE 2010s

In the past young adult novels have been very careful with their depictions of sex, usually alluding to it with a lovely romantic “fade out”. However, I’ve noticed a difference in the past few years as more and more novels are being more umm, specific, in the descriptions of sex. In addition to including these moments, characters have also had discussions about their feelings, whether positive or negative, towards sex and their sexual identity. I’ve also noticed an increase in a discussions of consent regarding sex as the couple in question has a healthy chat prior and often the subject of protection is addressed as well.

Rich In Color

The fade out trope when applied to sex is also known as ‘pan to curtain’.

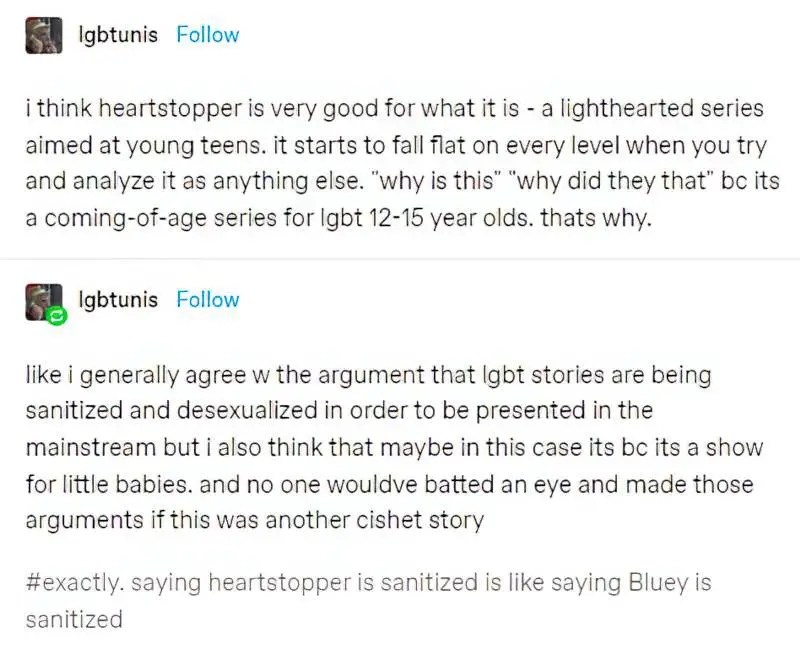

Asexuality and aromanticism barely get a mention, though this started to change near the end of the 2010s. Come early 2020s, Alice Oseman’s YA novels are serving as tentpole ace-spec representation, bringing stories of on-the-page sexuality into the broader public’s consciousness, especially since the adaptation of Heartstopper for Netflix. The author has promised fans more development of asexuality in subsequent adaptations. Oseman writes entire casts of queer characters, each with their own identity. Some critical readers expect authors to write within their own identities, and only within their own identities. This is, of course, impossible. Besides, an author who does that will attract the inverse charge: Failing to be sufficiently representative, and unrealistically surrounding a single queer character dealing with cishetallos. Asexual characters remain few and far between in any kind of literature, but YA is leading the charge. Most of these asexual characters are white.

FURTHER READING

What’s Going On Inside Of Me? Emergent female sexuality and identity formation in young adult literature, by Evelyn Baldwin

Emily Maguire is an Australian author, including of young adult novels such as Taming The Beast. In this article she explains what it was like to be a teenager, sex-drive-wise. It’s an awesome article.

Scarleteen is an excellent online resource for teenagers. Tagline: Sex Education For The Real World

Key findings of The Talk: How Adults Can Promote Young People’s Healthy Relationships and Prevent Misogyny and Sexual Harassment

- Teens and adults tend to greatly overestimate the size of the “hook-up culture” and these misconceptions can be detrimental to young people.

- Large numbers of teens and young adults are unprepared for caring, lasting romantic relationships and are anxious about developing them. Yet it appears that parents, educators and other adults often provide young people with little or no guidance in developing these relationships. The good news is that a high percentage of young people want this guidance.

- Misogyny and sexual harassment appear to be pervasive among young people and certain forms of gender based degradation may be increasing, yet a significant majority of parents do not appear to be talking to young people about it.

- Many young people don’t see certain types of gender-based degradation and subordination as problems in our society.

- Research shows that rates of sexual assault among young people are high. But our research suggests that a majority of parents and educators aren’t discussing with young people basic issues related to consent.

Provocauteurs and Provocations: Screening Sex in 21st Century Media

Twenty-first century media has increasingly turned to provocative sexual content to generate buzz and stand out within a glut of programming. New distribution technologies enable and amplify these provocations, and encourage the branding of media creators as “provocauteurs” known for challenging sexual conventions and representational norms.

While such strategies may at times be no more than a profitable lure, the most probing and powerful instances of sexual provocation serve to illuminate, question, and transform our understanding of sex and sexuality. In Provocauteurs and Provocations: Screening Sex in 21st Century Media (Indiana UP, 2021), award-winning author Maria San Filippo looks at the provocative in films, television series, web series and videos, entertainment industry publicity materials, and social media discourses and explores its potential to create alternative, even radical ways of screening sex.

Throughout this edgy volume, San Filippo reassesses troubling texts and divisive figures, examining controversial strategies–from “real sex” scenes to scandalous marketing campaigns to full-frontal nudity–to reveal the critical role that sexual provocation plays as an authorial signature and promotional strategy within the contemporary media landscape.

New Books Network

Header illustration: Flash from an Old Flame, Cosmopolitan- January 1957 by Bernard D’Andrea