The Secret Garden is a novel by British-American Frances Hodgson Burnett, originally published in serialised form in America between 1910-11, the end of the Edwardian era in England. We now consider this a story for children, probably because the main characters are children. Surprising to me: this story was originally aimed at an adult readership.

When I think a little harder though, it makes sense that The Secret Garden was aimed at adult readers. If there’s a moral in this story, it’s aimed at parents. At times it sounds like a parenting manual:

Two worst things as can happen to a child is never to have his own way – or always to have it.

The Secret Garden

If we’re going to call it children’s literature,The Secret Garden is an example from the First Golden Age of Children’s Literature, which lasted from 1850 until the first World War. In some ways it’s typical of its time, in other ways ahead of its time.

The Secret Garden utilises a madwoman in the attic trope, though the prisoner is a boy, not a madwoman. The haunted house and grounds are also straight out of a Gothic horror. The Secret Garden is a very clear example of the Gothic in literature. It is also clearly Christian.

I’m reading an abridged version, which is still plenty long. Though some child readers absolutely stan this novel, I don’t personally consider it children’s literature. In fact, I didn’t plan on ever digging deep into this novel because it gave me the absolute creeps when I was a kid myself.

My childhood copies and they’re still on the shelf. I started reading a few times and never finished. Then, in the year of our Lord 2020, when my own kid was in Year 6 and refused to study White Fang along with everyone else due to the animal cruelty contained within, their teacher handed them a copy of The Secret Garden instead (because child cruelty is more palatable than animal cruelty…) Hodgson Burnett’s classic has clearly found resonance if you can still find class sets hanging around in Australian schools.

Notably, my own kid also despised The Secret Garden and, like me, couldn’t get past the first few chapters. Without whole class guidance from the teacher (who had actually prepped for a unit on White Fang), it was impossible to understand.

As an adult, I have since read a completely different kind of book with a similar name: Nancy Friday’s My Secret Garden, which puts a whole different spin on things.

Listen to The Secret Garden at Librivox

My Secret Garden exploded on to bestseller lists around the globe in 1973. The work was shocking, deeply sexy in parts and proved that women had erotic imaginations just as men did, and that they, too, masturbated just as men did. It heralded the innocent dawning of what later became known as the sex-positive feminist movement.

The Guardian

Read Nancy Friday’s collection of women’s fantasies and it’s difficult not to go back and read the children’s book garden as a metaphor for Mary’s private world of erotic fantasy.

RACE ISSUES

This isn’t why The Secret Garden sometimes finds itself on banned book lists. There’s nothing on-the-page sexualised about this novel. It’s banned for the racist language and viewpoints. The following comes from Martha, portrayed as a sensible, empathetic character:

“It is different in India,” said Mistress Mary disdainfully. She could scarcely stand [the thought of looking after herself].

But Martha was not at all crushed.

“Eh! I can see it’s different,” she answered almost sympathetically. “I dare say it’s because there’s such a lot o’ blacks there instead o’ respectable white people.”

Martha then goes on to say she’s disappointed that Mary is not black. She was looking forward to someone different. But this hardly cancels out the first part of what she said, and the era-appropriate but nonetheless damaging othering.

For many years, the idea of talking about racism in children’s books was controversial. It was one thing to discuss whether a children’s book was racist, although that in itself was controversial and certainly only something to be done by adults. It was quite another thing for children’s books to directly address racism in society.

Beyond the Secret Garden: Talking About Racism in Children’s Books at Books For Keeps

DISABILITY ISSUES

Let’s add to that some disability issues in which a happy ending for a disabled character is that he suddenly (miraculously) learns he can walk after all. The reader is to code Colin’s inability to walk as psychological from the get-go. Bear in mind, Burnett’s notion of cures came from Christian Science.

The Secret Garden […] presents ideas that could certainly be called subversive, since at the time they were new and of dubious reputation. In this case, however, they are ideas about religion, psychology, and health. Colin’s self-hypnotic chanting recalls the sermons of Christian Science or New Thought, in both of which Mrs. Burnett [the author] was interested. The idea that illness is often largely psychological, and can be cured by positive thinking, permeates [The Secret Garden]. Another new concept is that of the healing power of nature, of fresh air and outdoor exercise.

Today we take ideas like this for granted, but Mrs. Burnett grew up in an age when the only exercise permitted to middle-class women was going for walks. The Secret Garden also shows the influence of the new paganism that found a following among liberal intellectuals of the time. It contains a kind of nature spirit in Dickon, the farm boy who spends whole days on the moors talking to plants and animals and who is a sort of cross between Kipling’s Mowgli and the many adult incarnations of the rural [man-beast god] Pan who appear in Edwardian fiction.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grownups: The subversive power of children’s literature

I agree with the take below. As usual, it’s not the individual story which proves problematic… if a story could ever possibly exist in isolation. The Secret Garden‘s place in a wider corpus of thought and art is the problematic thing:

On the page, Colin’s story is haunting. In context of a larger literature that has relatively few complex characters with disabilities, the diagnosis of “it’s all in his head” feels disappointing.

The Guardian

SETTING OF THE SECRET GARDEN

PERIOD

the turn of the 20th century. Or “fin de siècle” to sound fancy.

LOCATION

The story begins in India, but Mary is soon sent to live with her wealthy uncle at his isolated mansion, Misselthwaite Manor, on the Yorkshire Moors.

For another middle grade story set on the moors, featuring a big, scary house…

Creepy Direspire Hall sits glowering on the moors – and if you stray too close then beware the growls and scary sounds from within… When animal lover Cora learns that Direspire’s mysterious owner is looking for a new Creature Keeper, she realises this might just be the chance she’s looking for to save her parents’ farm. But Direspire Hall is a spooky place and the strange creatures who live there are nothing like Cora is expecting. As Cora settles into her new life, it soon becomes clear that Direspire has its secrets, and that somebody will do whatever it takes to keep them…

ARENA

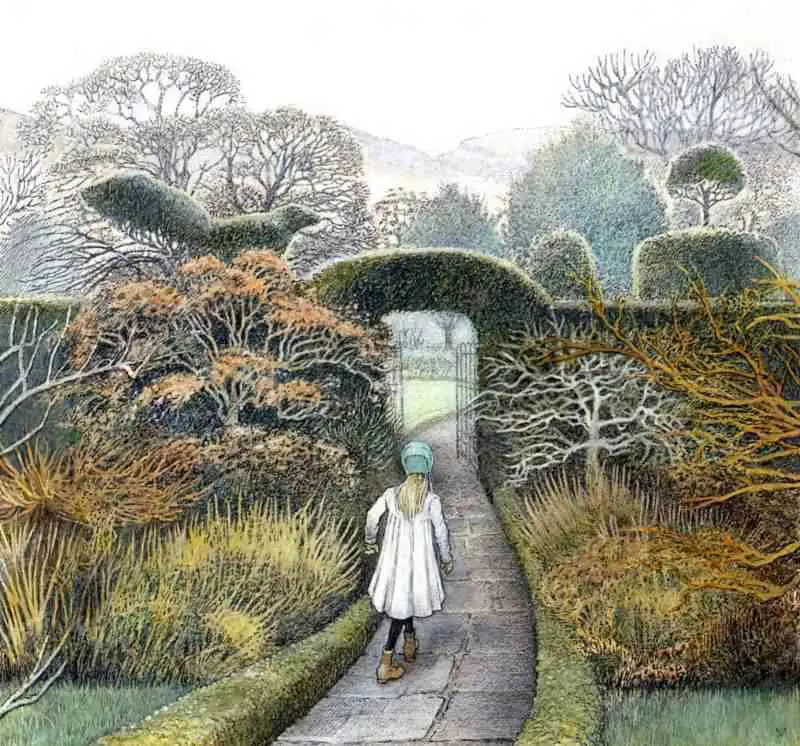

Mostly takes place at Misselthwaite Manor, but there is a secret garden there which acts a little like mise en abyme (a smaller thing within a bigger thing), or perhaps more like a heterotopia.

At first each day which passed by for Mary Lennox was exactly like the others. Every morning she awoke in her tapestried room and found Marha kneeling upon the hearth building her fire; every morning she ate her breakfast in the nursery which had nothing amusing in it; and after each breakfast she gazed out of the window across to the huge moor, which seemed to spread out on all sides and climb up to the sky, and after she had stared for a while she realized that if she did not go out she would have to stay in and do nothing—and so she went out.

The Secret Garden

MANMADE SPACES

a 600-year-old Gothic mansion with a with a hundred mostly unused rooms and a private walled garden in the grounds. This terrifying house is reminiscent of “Bluebeard” tales, which take various forms around the world and across history. When it comes to massive houses with exactly 100 rooms, there is a story in The Arabian Nights. In this story, Prince Agib has 100 keys to 100 doors and may open them all except the golden one.

If you look the right way, you can see that the whole world is a garden.

The Secret Garden

The lack of lights at Misselthwaite Manor succinctly conveys the unwelcoming vibe. Next we get a portrait of a place full of crossbars, divided into multiple frames, about to serve as a jail:

At first Mary thought that there were no lights at all in the windows, but as she got out of the carriage she saw that one room in a corner upstairs showed a dull glow.

The entrance door was a huge one made of massive, curiously shaped panels of oak studded with big iron nails and bound with great iron bars. It opened into an enormous hall, which was so dimly lighted that the faces in the portraits on the walls and the figures in the suits of armour made Mary feel that she did not want to look at them. As she stood on the stone floor she looked a very small, odd little black figure, and she felt as small and lost and odd as she looked.

The Secret Garden

Within the garden, the roses stand metonymically for ‘beauty’, and in this sentence, for Mary’s beauty (or supposed lack thereof):

“It isn’t a quite dead garden,” she creid out softly to herself. “Even if the roses are dead, there are other things alive.”

The Secret Garden

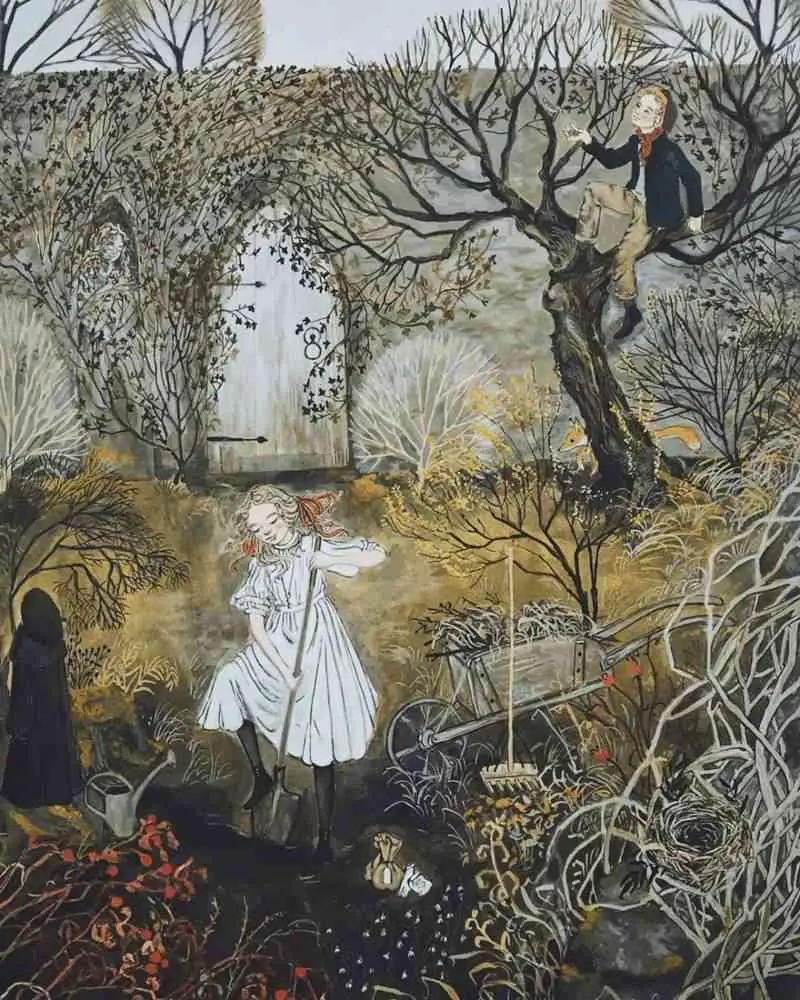

The garden has two distinct parts to it.

One place she went to oftener than to any other. It was the long walk outside the gardens with the walls round them. It seemed as if for a long time that part had been neglected. The rest of it had been clipped and made to look neat, but at this lower end of the walk it had not been trimmed at all.

The Secret Garden

NATURAL SETTINGS

Unlike the rest of the land of this estate, the garden has returned to its natural state. The wall is covered in roses. If you’ve ever tried to dig roses out of your garden you’ll be familiar with how hard they are to kill, which is ironic considering how much TLC they need before flowering. This garden has a softening quality on Mary, suggesting a magical power. This restorative power is connected to the idea that nature (good country air) is beneficial to children. The good country air stands in contrast to industrial cities and civilisation. The city makes children undesirably sophisticated and cloistered.

The book rests upon the idea that you become good by doing good. Good acts don’t leave room for the bad. Gardening is a metaphor for the work we must do on ourselves: plant flowers so weeds can’t grow.

Where you tend a rose my lad, a thistle cannot grow.

The Secret Garden

“Of course there must be lots of Magic in the world,” he said wisely one day, “but people don’t know what it is like or how to make it. Perhaps the beginning is just to say nice things are going to happen until you make them happen. I am going to try and experiment.”

The Secret Garden

One of the new things people began to find out in the last century was that thoughts—just mere thoughts—are as powerful as electric batteries—as good for one as sunlight is, or as bad for one as poison. To let a sad thought or a bad one get into your mind is as dangerous as letting a scarlet fever germ get into your body. If you let it stay there after it has got in you may never get over it as long as you live… surprising things can happen to any one who, when a disagreeable or discouraged thought comes into his mind, just has the sense to remember in time and push it out by putting in an agreeable determinedly courageous one. Two things cannot be in one place.

The Secret Garden

WEATHER

India is hot, steamy and coddles Mary in a similar way the servants coddle her. The Yorkshire air is bracing (and healthy). This is the sort of air you need if you’re going to have a character arc! ‘[Mary’s] hair was yellow, and her face was yellow because she had been born in India…’ During this First Golden Age of Children’s Literature, we can see how the colour yellow was linked by Westerners to Asia. Mary is described as yellow because of India.

“Is the spring coming?” he said. “What is it like?”…

The Secret Garden

“It is the sun shining on the rain and the rain falling on the sunshine…”

The wind of The Secret Garden plays a large role, sometimes personified:

She made herself stronger by fighting with the wind.

The Secret Garden

In fact, it was the wind which Martha says killed Mrs Craven. She was sitting on a branch. The wind is meant to have knocked it down..

Mary did nto ask any more questions. Shje looked at the fire and listened to the wind “wuthing’”. It seemed to be “wuthering’” louder than ever.

The Secret Garden

But as she was listening to the wind she began to listen to something else. She did not know what itw as, because at first she could scarcely distinguish it from the wind itself. It was a curious sound — it seemed almost as if a child were crying somewhere.

Martha says that the wind does sometimes sound like “someone was lost on the moor an’ wailin’”. (The ‘wind’ turns out to be the locked up son of the dead woman.)

The rain in this story is oppositional. When it is raining Mary is unable to play outside, which is her new favourite thing to do. However, it is because of rain keeping her awake (and bored stiff) in the middle of the night that prompts her to wander the corridors with a candle and find Colin.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

Technology is what we’d expect of a novel from the turn of the 20th century. Is there magic, though? There is magic in nature:

Sometimes since I’ve been in the garden I’ve looked up through the trees at the sky and I have had a strange feeling of being happy as if something was pushing and drawing in my chest and making me breathe fast. Magic is always pushing and drawing and making things out of nothing. Everything is made out of magic, leaves and trees, flowers and birds, badgers and foxes and squirrels and people. So it must be all around us. In this garden – in all the places.

The Secret Garden

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

At the beginning of the story a cholera epidemic has killed Mary’s parents. There’s no good social security. Society turns a blind eye to orphans. Nor do the servants of Mary’s parents feel any duty of care towards Mary. They take off as soon as they realise their employers are dead and will no longer have a job.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

Mary therefore finds herself utterly alone. This backstory would be completely traumatic for anyone, let alone a child. British soldiers place her in the care of an English clergyman.

This is the ultimate ‘Children should be seen and not heard’ story. See: English Childhood in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

PRELAPSARIAN, CARNIVALESQUE AND POSTLAPSARIAN

Children’s literature academic Maria Nikolajeva categorises children’s fiction into three general forms:

- Prelapsarian (when the main characters are unspoiled by ‘The Fall of Man’. The setting tends to be pastoral, secluded, autonomous. The main characters tend to be ensembles. The narrative voice tends to be didactic and omniscient. Time is circular, with much use made of the ‘iterative’ rather than the ‘singulative’. Utopian fiction introduces readers to the sacred.)

- Carnivalesque (in which the characters temporarily take over from figures of authority and often make mischief, but control their own worlds for a time. See: The Hobbit, Narnia Chronicles, Harry The Dirty Dog. Carnivalesque texts take children out of Arcadia but ensure a sense of security by bringing them back. They allow an introduction to death, which inevitably follows the insight about the linearity of time.)

- Postlapsarian (in which a pastoral setting tends to be replaced by an urban one, and collective protagonists are exchanged for individuals. First person point of view is common. Time is linear. The main character knows that time is linear, so death becomes a central theme. Harmony gives way to chaos. Postlapsarian children’s literature interrogates the social, moral, political, and sexual innocence of the child. These texts exist to introduce children to adulthood and death, and encourages them to grow up, or helps them out with it. In these stories, there is no going back.)

The Secret Garden is the standout example of Prelapsarian fiction.

Intertextuality

There’s an on-the-page reference to “Sleeping Beauty“.

The Secret Garden was what Mary called it when she was thinking of it. She liked the name, and she liked still more the feeling that when its beautiful old walls shut her in no one knew where she was. It seemed almost like being shut out of the world in some fairy place. The few books she had read and liked had been fairy-story books, and she had read of secret gardens in some of the stories. Sometimes people went to sleep in them for a hundred years, which she had thought must be rather stupid. She had no intention of going to sleep, and, in fact, she was becoming wider awake every day which passed at Misselthwaite.

The Secret Garden

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE SECRET GARDEN

PARATEXT

Mary Lennox is born in India to wealthy British parents who never wanted her. When her parents suddenly die, she is sent back to England to live with her uncle. She meets her sickly cousin, and the two children find a wondrous secret garden lost in the grounds of Misselthwaite Manor.

SYNOPSIS FOR THE 2020 FILM ADAPTATION

SHORTCOMING

In the opening paragraph the author describes Mary s selfish, sour and rude. You don’t read such harsh descriptions of children in contemporary children’s literature, except in works which aim to spoof, e.g. Roald Dahl and David Walliams et al:

By the time she was six years old she was as tyrannical and selfish a little pig as ever lived.

The Secret Garden

Her disagreeableness is meant to be because she is unloved, cared for by native servants, not by her own parents. It is taken for granted that this is what happens when rich people entrust the care of a child to paid servants.

In reality, is this what happens? A child brought up by paid native servants may in fact be better adjusted than if they were brought up in the extended company of wealthy colonialist settlers. She’d be busting out with even more crap like, “They are not people – they’re servants who must salaam to you.” It’s the sudden ripping away of those servants which causes most of the trauma. Imagine waking up one morning to find someone you know and love has disappeared forever. It’s about to get so much worse. Is ‘cross’ really the right word?

The Secret Garden would’ve felt revolutionary in a proto-feminist way because Mary Lennox is no Pollyanna (the title character of Eleanor H Porter’s 1913 novel). She is flawed. And unless a femme character is allowed flaws, there is no room for her character arc; ergo, she can never be the true star of the story:

[The Secret Garden] takes the traditional children’s literature trope of the orphan protagonist and twists it. Mary Lennox is not a good-hearted, put-upon creature, cut from the cloth of Oliver Twist or Cinderella (or Anne Shirley, Pip, Jane Eyre or Heidi). Rather she is spoiled, homely, mean and sometimes violent.

The Guardian (I disagree about Anne Shirley being a character without moral and psychological weakness.)

That said, the author of The Guardian article points out that the disagreeableness of Mary is ‘not to be confused with rascally Tom Sawyer-style mischievousness’. When female characters are rendered with moral flaws, they are both written to be more unlikeable and perceived as more unlikeable. (This is exactly what we’d expect from the rules of misogyny which undergird society.) When thinking about the gendered nature of likeability, The Secret Garden makes a good case study because it includes not just one spoilt brat but two — first in Mary, then in Colin. We might do a compare and contrast on that. Reading through my modern lens, I think both children have been severely abused and their trauma is coded as selfishness. (Because when you’ve been traumatised you don’t exactly have spoons for anyone else.)

Mary Lennox is the mother of Disney’s Snow White in many ways, and people have been arguing for years about whether Snow White is a feminist hero or not. Snow White is another young woman living in traumatic conditions. Both of them have birds as their best friends. Unlike the earlier Mary Lennox, Snow White has no moral shortcoming; she isn’t mean to others. (I kind of actually want her to be.)

DESIRE

Hodgson Burnett builds up the reader’s interest in this garden by creating a mythology around it. When Martha tells Mary about Lilias Craven who died in the secret garden, Mary wants to see inside.

Now Mary is Pandora from the Greek mythology, wanting to see inside something which has been locked by a man for her own good, and for the good of everyone else. She’s also freaked out by some mysterious cries she hears at night.

OPPONENTS AND ALLIES

Some stories introduce a mystery in lieu of an opponent. This story has plenty of both. The mystery is the cause of the wailing Mary hears from a distant corner of the large house.

In America, the English clergyman’s children taunt Mary by calling her “Mistress Mary, quite contrary“.

Mary’s mother — a beautiful woman who loves parties. Many of the adults portrayed in The Secret Garden keep bringing up the fact that Mary’s mother was beautiful. The fact that she loves parties tells us she’s a selfish mother, I guess. This is also an example in which a woman’s beauty hasn’t been good for her moral development. When ‘good’ characters like Martha and Susan Sowerby keep bringing it up as a negative, we accept it as a negative. Mary is plain, so has more chance at becoming humble and wise. We are constantly encouraged to be critical of Mary’s neglectful, beautiful, party-lovin mother.

Colin’s mother — Mary’s mother and Colin’s mother were sisters. (Off the page.)

Archibald Craven — Mary’s uncle. This guy’s name alone should tell us he is the true villain of the piece. After his wife died giving birth to their son, he left the son locked up in a room inside the house and psychologically abused him to the point where he suffers severe health anxiety and can’t walk. Archibald Craven is constantly looking sad. We are constantly encouraged to feel empathetic towards Mary’s neglectful, abusive uncle.

Mrs Martha Sowerby — Starts off in opposition to Mary, who has a tantrum when she meets Martha. Teenage Martha shows herself to be a good-natured maid who tells Mary about Mary’s dead aunt. Buys Mary a skipping rope which she skips with in the garden.

Mr Sowerby — We never hear anything about him.

Mrs Medlock — the housekeeper, like everyone else, ignores the unattractive girl and hides her far from others. Like Mr Craven, she has a symbolic name, ‘locking’ children away.

Dickon — Martha’s 12-year-old brother, who provides Mary with gardening tools. As a good child of the country, Dickon is kind to both animals and people. He has plenty of gardening knowledge, and Mary is keen to learn from him. Narratively speaking, Dickon resembles a demigod Pan-like nature deity (which you’ll also find in The Wind In The Willows, if you’re reading an unabridged version). He’s even playing on ‘a rough wooden pipe’ when Mary first meets him in the garden. Mary asks Dickon, “Do you like me?” Dickon is the only human character who likes her, in line with a Jesus figure (who loves all the little children).

The robin — It is this fairy tale bird, like something straight out of “Hansel and Gretel” or “The Juniper Tree” which draws Mary’s attention to an area of disturbed soil. This is where Mary finds the key to the locked garden, and eventually the door.

Nothing in the world is quite as adorably lovely as a robin when he shows off and they are nearly always doing it.

The Secret Garden

Though this particular robin is a happy one, in art there are many images of dead robins, feet in the air, red breasts up. I guess it’s their redness which make us think of blood, which make us think of death. The robin might represent the spirit of Colin’s deceased mother.

Colin — The Secret Garden makes use of ghost tropes, but it ends up being an Explained Ghost (showing the reader not to be silly and believe in supernatural rubbish). This is not a ghost making weird noises in the night, but a real live boy. He has been hidden by his father in a bedroom, Flowers In The Attic style. Colin is the son of Mr and the dead Mrs Craven. (Mary and Colin are cousins.) He suffers from an unspecified spinal problem which prevents him from walking.

With delayed decoding, it seems any failure to walk is as a result of him being shut up rather than any congenital issue or acquired disability. Are we talking Munchausen by proxy here? Normally it’s mothers who get the blame for this in fiction, but could Colin’s father be a rare male case? As you might expect, Colin has grown into an angry, self-loathing kid. He unnerves the servants and has a fear of becoming a hunchback. (I guess he’s read the 1831 novel by Victor Hugo.) Colin’s crying is described as tantrum.

Ben Weatherstaff — The gardener who climbs a ladder, looks over the wall of the secret garden and finds the children in the secret garden. He’s startled and angry about this. He admits that he believed Colin to be “a cripple”. He is too old and curmudgeonly to be considered nurturing, which leaves this story with no father figure, though there are some women who mother the children. (The unintended message is that children need their mothers but fathers are a nice add-on.) Like Mary, Ben Weatherstaff describes himself as lonely, and the robin the only friend he has got.

“Tha’ an’ me are a good bit alike… We was wove out of th’ same cloth. We’re neither of us good-lookin’ an’ we’re both of us as sour as we look. We’ve got the same nasty tempers, both of us, I’ll warrant.”

Ben Weatherstaff, The Secret Garden

Ben Weatherstaff functions as the patriarchy which punishes girls/women for asking too many questions (which don’t concern them). To ask questions is to push back against existing power structures.

“Now look here!” he said sharply. “Don’t tha’ ask so many questions. Tha’rt the worst wench for askin’ questions I’ve ever come across. Get thee gone an’ play thee. I’ve done talkin’ for today.”

The Secret Garden

PLAN

Like many child characters in books, Mary starts exploring the large house and grounds because she’s bored out of her brains. (Neil Gaiman utilises the same situation in his contemporary middle grade novel Coraline.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

When Colin gets out of his wheelchair and starts walking this reminds me of a scene from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, in which Charlie’s grandfather suddenly leaps out of bed and starts dancing when he learns Charlie has won a golden ticket. Use it or lose it; there’s no way this could ever happen. If Colin has never walked in his life, his leg muscles wouldn’t support him. Of course, this is not the point.

ANAGNORISIS

“I shall live forever and ever and ever ‘ he cried grandly. ‘I shall find out thousands and thousands of things. I shall find out about people and creatures and everything that grows – like Dickon – and I shall never stop making Magic. I’m well I’m well”

The Secret Garden

For Mary, it’s not a benefactor or romantic love that catalyses her growth. Rather, she learns to take care of herself, to experience un-lonely solitude in the natural landscape. She keeps company with local eccentrics from across the social spectrum, and begins to enjoy the movement of her body; her transformation begins when she learns to jump rope.

The Guardian

Children’s book writers utilise many techniques for getting adults out of the way, which allows child characters agency. Oftentimes the mother is dead. Not one but two mothers have been killed for this narrative.

In that respect, The Secret Garden is of its time, but it is revolutionary in a related way:

One of the book’s strangest features is that it is the two most wounded and unlikable characters who do the most to heal one another. The moral guidance of kindly adults doesn’t have much to do with it.

The Guardian

The ‘healing’ aspect is made very manifest in Colin, who goes from ‘unable to walk’ to ‘walking’. Mary’s healing is very much on the inside. These two parallel stories — one manifest, one private, remind me of a children’s(?) novel from the same era: The Wind In The Willows. In many ways these stories are completely different, but Toad’s spiritual journey is basically the carnivalesque outworking of the Mole’s inner journey.

Flawed characters each contributing to the character arc of one another is an excellent storytelling technique which can really move audiences. This storytelling technique is used in the best stories today. For one example, see the film Lady Bird, in which mother and daughter contribute to each other’s character arc. That example happens to be about a mother and daughter, but romance stories often use romantic opponents to the same end; each partner learns what they need from each other; ergo, they are coded as a good match. When the arc of one character is external, the other internal, and one arc helps the audience to understand the other, this is a sophisticated writing technique. The Secret Garden is a good early example.

In contrast we also get stories written in the Mary Poppins tradition. In these stories a boy and a girl are plonked into the narrative for marketing purposes rather than storytelling ones. In line with popular binary thinking, the girl is thought to appeal to girl readers, the boy to boy readers. That’s why they’re both there. But they might as well be the same character, as there’s nothing to distinguish between them. They don’t help each other to grow. They don’t help the audience to understand internal character arcs.

“When new beautiful thoughts began to push out the old hideous ones, life began to come back to [Colin], his blood ran healthily through his veins and strength poured into him like a flood.”

The Secret Garden

NEW SITUATION

Quite a few children’s novels have death, the fear of death, and “coping with death” as a central or peripheral motif, and writers can deal with death as an “issue” (“How to help children cope with the death of a relative”) or an existential* problem, in a realistic (Bridge to Terabithia) or fantastic (The Brothers Lionheart) mode. Most often, the person who dies in a children’s book is the protagonist’s older relative, quite often a pet (“transitional object”), more rarely a parent, occasionally a sibling or a friend. The event very rarely concludes the novel, as Forster suggests; on the contrary, it is introduced in the beginning to set the plot in motion. By the end of the book, the trauma has been successfully healed. In many novels, the parents’ death (utter form of “absence”), as in fairy tales, is the necessary prerequisite for the character’s quest (The Secret Garden).

The Rhetoric of Character in Children’s Literature, Maria Nikolajeva

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

Trauma has healed. About midway through the book we are told that Mary is ‘not a self-sacrificing person’ (hence she won’t go and sit by Colin’s bed if she would prefer to play outside with Dickon). But Mary becomes a more motherly and nurturing figure towards Colin, which is in line with what we see today of many girl characters in narrative: Pixar loves it.

The story ends with Dr Craven. By magic he’s suddenly started to care about his own son and there’s a happy reuniting at the end. This is an aristocratically happy ending because the father now has an heir — ‘natural order’ will continue.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

However many years she lived, Mary always felt that ‘she should never forget that first morning when her garden began to grow’.

The Secret Garden

A Goodreads user said the following:

I like to think that in the future Mary and Dickon get married and live in a nice cottage on the moor near Misselthwaite Manor. Her, Collin, and Dickon still take care of the garden and Mary and Dickon name their son Ben.

I believe this extrapolation is the intended one. Like the partners of a romance novel, these two have learned from each other, became better people in the other’s presence, and have therefore been proven good for each other. It’s not lost on me that they are cousins. Bear in mind that it is more WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic) NOT to marry your cousin than to marry them. If you don’t come from a Christian tradition, which forbid marriages within families some generations ago, you likely come from a culture in which marrying your cousin is encouraged. It is estimated that as many as 80% of the marriages in human history have been between first or second cousins.

The Secret Garden does feel a bit like a proto- love triangle of the sort we’ve seen in many narratives since, e.g. Twilight, in which Edward would map onto Colin and the sunnier Jacob would map onto Dickon. This triangle is much older than The Secret Garden, however; Frances Hodgson Burnett was probably influenced by Pride and Prejudice, featuring two male leads with contrasting dispositions, plus another who appears nice but who is actually terrible (Wickham).

RESONANCE

Copyright started expiring on The Secret Garden in 1987, which explains why I was gifted several copies. The story now exists in various forms: early readers, abridged, mass market cheap paperbacks, and has been adapted for film a number of times. In 1991, a Japanese anime version was launched for television in Japan.

Despite its obvious problems (racism and looksism stand out like sore thumbs), The Secret Garden is an early example of a feminist book. It only looks that way if we compare it to what came before rather than to contemporary stories. Unlike the corpus of stories which came before, Mary Lennox is a Pandora archetype who is not, in fact, punished for going where she’s not supposed to. Mary is rewarded for her feminine curiosity. In later stories, such as The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, a girl is also rewarded for exploring where she should not (also an old house belonging to a scary old man) and finding something wonderful.

Contrast with a much earlier children’s story like Rosamund and the Purple Jar, in which a girl is punished for caring so much about something and seeking to have it.

FURTHER READING

Frances Hodgson Burnett also wrote A Little Princess and Little Lord Fauntleroy. These two books were far more popular during her lifetime than The Secret Garden, but today The Secret Garden remains more popular than the other two.

I suspect audiences have a higher tolerance for ‘disagreeable girls’ as main characters than they did 100 years ago. Also, The Secret Garden lets children help each other towards moral goodness without adults dishing out instruction. This is another modern notion.

The “Norton Critical Edition” of The Secret Garden (2006) has great reviews for readers interested in the historical context but alas, I haven’t read it myself.

FURTHER READING

Secret: He has been let into thte secret; he has been cheated at gaming or horse-racing. He or she is in the grand secret; ie. dead.

from a 1703 dictionary of slang